Stanley Kubrick: Difference between revisions

Shirtwaist (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

|death_date = {{Death date and age|mf=yes|1999|3|7|1928|7|26}} |

|death_date = {{Death date and age|mf=yes|1999|3|7|1928|7|26}} |

||

|death_place = [[Harpenden]], [[Hertfordshire]], [[England]], [[United Kingdom]] |

|death_place = [[Harpenden]], [[Hertfordshire]], [[England]], [[United Kingdom]] |

||

|religion = [[ |

|religion = [[Judaism]] |

||

|cause of death = [[Heart failure]] |

|cause of death = [[Heart failure]] |

||

|spouse = Toba Metz (1948–1951; divorced)<br />[[Ruth Sobotka]] (1954–1957; divorced)<br />[[Christiane Kubrick|Christiane Harlan]] (1958–1999; his death) |

|spouse = Toba Metz (1948–1951; divorced)<br />[[Ruth Sobotka]] (1954–1957; divorced)<br />[[Christiane Kubrick|Christiane Harlan]] (1958–1999; his death) |

||

Revision as of 19:50, 10 June 2011

Stanley Kubrick | |

|---|---|

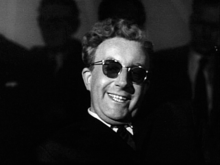

| File:KubrickForLook.jpg | |

| Born | July 26, 1928 |

| Died | March 7, 1999 (aged 70) |

| Occupation(s) | Film director, film producer, screenwriter, cinematographer, film editor |

| Years active | 1951–1999 |

| Spouse(s) | Toba Metz (1948–1951; divorced) Ruth Sobotka (1954–1957; divorced) Christiane Harlan (1958–1999; his death) |

Stanley Kubrick (July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American film director, writer, producer, and photographer who lived in England during most of the last four decades of his career. Kubrick was noted for the scrupulous care with which he chose his subjects, his slow method of working, the variety of genres he worked in, his technical perfectionism, and his reclusiveness about his films and personal life. He maintained almost complete artistic control, making movies according to his own whims and time constraints, but with the rare advantage of big-studio financial support for all his endeavors.

Kubrick's films are characterized by a formal visual style and meticulous attention to detail—his later films often have elements of surrealism and expressionism that eschews structured linear narrative. His films are repeatedly described as slow and methodical, and are often perceived as a reflection of his obsessive and perfectionist nature.[1] A recurring theme in his films is man's inhumanity to man. While often viewed as expressing an ironic pessimism,[2] a few critics feel his films contain a cautious optimism when viewed more carefully.[3]

The film that first brought him attention to many critics was Paths of Glory, the first of three films of his about the dehumanizing effects of war. Many of his films at first got a lukewarm reception, only to be years later acclaimed as masterpieces that had a seminal influence on many later generations of film-makers. Considered especially groundbreaking was 2001: A Space Odyssey noted for being both one of the most scientifically realistic and visually innovative science-fiction films ever made while maintaining an enigmatic non-linear storyline. He voluntarily withdrew his film A Clockwork Orange from Great Britain, after it was accused of inspiring copycat crimes which in turn resulted in threats against Kubrick's family. His films were largely successful at the box-office, although Barry Lyndon performed poorly in the United States. Living authors Anthony Burgess and Stephen King were both unhappy with Kubrick's adaptations of their novels A Clockwork Orange and The Shining respectively, and both authors were engaged with subsequent adaptations. All of Kubrick's films from the mid-1950s to his death except for The Shining were nominated for Oscars, Golden Globes, or BAFTAs. Although he was nominated for an Academy Award as a screenwriter and director on several occasions, his only personal win was for the special effects in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Even though all of his films, apart from the first two, were adapted from novels or short stories, his works have been described by Jason Ankeny and others as "original and visionary". Although some critics, notably Andrew Sarris and Pauline Kael, frequently disparaged Kubrick's work,[4] Ankeny describes Kubrick as one of the most "universally acclaimed and influential directors of the postwar era" with a "standing unique among the filmmakers of his day."[5]

Early life

Stanley Kubrick was born on July 26, 1928, at the Lying-In Hospital in Manhattan, New York, the first of two children born to Jacques Leonard Kubrick (1901–85) and his wife Gertrude (née Perveler; 1903–85). His sister, Barbara, was born in 1934. Jacques Kubrick, whose parents and paternal grandparents were Jewish of Austrian, Romanian and Polish origin,[6][7] was a doctor. At Stanley's birth, the Kubricks lived in an apartment at 2160 Clinton Avenue in The Bronx.[8]

Kubrick's father taught him chess at age twelve, and the game remained a lifelong obsession.[8] He also bought his son a Graflex camera when he was thirteen, triggering a fascination with still photography. As a teenager, Kubrick was interested in jazz, and briefly attempted a career as a drummer.[8]

Kubrick attended William Howard Taft High School from 1941 to 45. He was a poor student, with a meager 67 grade average.[9] He graduated from high school in 1945, but his poor grades, combined with the demand for college admissions from soldiers returning from the Second World War, eliminated any hopes of higher education. Later in life, Kubrick spoke disdainfully of his education and of education in general, maintaining that nothing about school interested him.[8] His parents sent him to live with relatives for a year in Los Angeles in the hopes that it would help his academic growth.

While still in high school, he was chosen as an official school photographer for a year. In 1946, since he was not able to gain admission to day session classes at colleges, he briefly attended evening classes at the City College of New York (CCNY) and then left.[10] Eventually, he sought jobs as a freelance photographer, and by graduation, he had sold a photographic series to Look magazine. Kubrick supplemented his income by playing chess "for quarters" in Washington Square Park and various Manhattan chess clubs.[11] He became an apprentice photographer for Look in 1946, and later a full-time staff photographer. (Many early [1945–50] photographs by Kubrick have been published in the book Drama and Shadows [2005, Phaidon Press] and also appear as a special feature on the 2007 Special Edition DVD of 2001: A Space Odyssey.)

During his Look magazine years, Kubrick married Toba Metz (b. 1930) on May 29, 1948. They lived in Greenwich Village, eventually divorcing in 1951. During this time, Kubrick began frequenting film screenings at the Museum of Modern Art and the cinemas of New York City. He was particularly inspired by the complex, fluid camerawork of director Max Ophüls, whose films influenced Kubrick's later visual style.

Film career and later life

Early works

In 1951, Kubrick's friend Alex Singer persuaded him to start making short documentaries for The March of Time, a provider of newsreels to movie theatres. Kubrick agreed, and shot the independently financed Day of the Fight in 1951. The film notably employed a reverse tracking shot, which would become one of Kubrick's signature camera movements.[12] Although its distributor went out of business that year, Kubrick has been said to have sold Day of the Fight to RKO Pictures for a profit of $100,[13] although Kubrick himself said he lost $100 in Jeremy Bernstein, Interview With Stanley Kubrick in 1966.[14] Inspired by this early success, Kubrick quit his job at Look magazine and began working on his second short documentary, Flying Padre (1951), funded by RKO. A third short film, The Seafarers (1953) was filmed just after his first feature Fear and Desire (see below) in order to recoup costs. It was a 30-minute promotional film for the Seafarers' International Union and was Kubrick's first color film. These three films constitute Kubrick's only surviving work in the documentary genre. It is believed, however, that he was involved in other shorts, which have been lost—most notably World Assembly of Youth (1952).[15] He also served as second unit director on an episode of the Omnibus television program about the life of Abraham Lincoln. None of these shorts has ever been officially released, though they have been widely bootlegged, and clips are used in the documentary Stanley Kubrick: A Life In Pictures. In addition, Day of the Fight and Flying Padre have been shown on TCM.

1950s: Fear and Desire, Killer's Kiss, The Killing and Paths of Glory

Kubrick moved to narrative feature films with Fear and Desire (1953), the story of a team of soldiers caught behind enemy lines in a fictional war. While wracked with anxiety about how they will escape, they stumble across a woman whom they capture for fear of her reporting them. One of the soldiers begins to fall in love with her, but shoots her when she tries to escape. He then abandons the troop. Another soldier becomes unsatisfied with a simple escape down the river and persuades the remaining soldiers to engage in a scheme to kill a general in a surprise attack at a nearby base.

Kubrick and his then-wife, Toba Metz, were the only crew on the film, which was written by Kubrick's friend Howard Sackler, who later became a successful playwright. Fear and Desire garnered respectable reviews but was a commercial failure. Later in life, Kubrick was embarrassed by the film, which he dismissed as an amateur effort. He refused to allow Fear and Desire to be shown at retrospectives and public screenings and did everything possible to keep it out of circulation.[16] At least one copy remained in the archives of the film printing company, and the film subsequently surfaced in bootleg copies.

Kubrick's marriage to Toba Metz ended during the making of Fear and Desire. He met his second wife, Austrian-born dancer and theatrical designer Ruth Sobotka, in 1952. They lived together in New York's East Village from 1952 until their marriage on January 15, 1955. They moved to Hollywood that summer. Sobotka, who made a cameo appearance in Kubrick's next film, Killer's Kiss (1955), also served as art director on The Killing (1956). Like Fear and Desire, Killer's Kiss is a short feature film, with a running time of slightly more than an hour. It met with limited commercial and critical success. The film is about a young heavyweight boxer at the end of his career who gets involved in a love triangle in which his rival is involved with organized crime. Both Fear and Desire and Killer's Kiss were privately funded by Kubrick's family and friends.[17][18]

Alex Singer introduced Kubrick to a young producer named James B. Harris, and the two became close friends.[19] Their business partnership, Harris-Kubrick Productions, would finance Kubrick's next three films. The two bought the rights to the Lionel White novel Clean Break, which Kubrick and co-screenwriter Jim Thompson turned into The Killing. The story is about a meticulously planned racetrack robbery gone wrong after the mobsters get away with the money. (The film title may refer either to the robbery or the subsequent murder of a group of mobsters by a jealous boyfriend). Starring Sterling Hayden, The Killing was Kubrick's first full-length feature film shot with a professional cast and crew. As does the novel's narration, the story in the film is told out of sequence in a non-linear narrative as a consequence of retelling the events of the same day (and sometimes the same events) from the perspective of different characters. (This is not the same as using successive multiple in-world flashbacks as Citizen Kane does.) While this technique was highly unusual for contemporary 1950s American cinema, it was imitated nearly 40 years later in Reservoir Dogs by director Quentin Tarantino who has acknowledged Kubrick's film as a major influence,[20] and critics have noticed the similarity in plot structure.[21] In many ways, The Killing followed the conventions of film noir, both in its plotting and cinematography style. That kind of crime caper film had peaked in the 1940s; but today, many regard this film as one of the best of the noir genre.[22] While it was not a financial success, it received good reviews.[23]

The widespread admiration for The Killing brought Harris-Kubrick Productions to the attention of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.[24] The studio offered them its massive collection of copyrighted stories from which to choose their next project. During this time, Kubrick also collaborated with Calder Willingham on an adaptation of the Austrian novel The Burning Secret. Although Kubrick was enthusiastic about the project, it was eventually shelved.[25]

Kubrick's next film Paths of Glory was set during World War I and based on Humphrey Cobb's 1935 antiwar novel of the same name. It follows a French army unit ordered on an impossible mission by their superiors. As a result of the mission's failure, three innocent soldiers are charged with cowardice and sentenced to death, allegedly as an example to the troops, but actually serving as scapegoats for the failings of their commanders. Kirk Douglas was cast as Colonel Dax, a humanitarian officer who tries to prevent the soldiers' execution. Douglas was instrumental in securing financing for the ambitious production. The film was not a significant commercial success, but it was critically acclaimed and widely admired within the industry, establishing Kubrick as a major up-and-coming young filmmaker. Critics over the years have praised the film's unsentimental, spare, and unvarnished combat scenes and its raw, black-and-white cinematography.[26] Steven Spielberg has named this one of his favorite Kubrick films.[27]

During the production of Paths of Glory in Munich, Kubrick met and romanced young German actress Christiane Harlan (credited by her stage name, "Susanne Christian"), who played the only female speaking part in the film. Kubrick divorced his second wife, Ruth Sobotka, in 1957. Christiane Susanne Harlan (b. 1932 in Germany) belonged to a theatrical family and had trained as an actress. She and Kubrick married in 1958 and remained together until his death in 1999. During her marriage to Kubrick, Christiane concentrated on her career as a painter.[28] In addition to raising Christiane's young daughter Katharina (b. 1953) from her first marriage to the late German actor Werner Bruhns (d. 1977), the couple had two daughters, Anya (1959–2009) and Vivian (b. 1960). Christiane's brother Jan Harlan was Kubrick's executive producer from 1975 onward.

1960s: Spartacus, Lolita, Dr. Strangelove and 2001: A Space Odyssey

Upon his return to the United States, Kubrick worked for six months on the Marlon Brando vehicle One-Eyed Jacks (1961). The two clashed over a number of casting decisions, and Brando eventually fired him and decided to direct the picture himself.[29] Kubrick worked on a number of unproduced screenplays, including Lunatic at Large, which Kubrick intended to develop into a movie,[30] until Kirk Douglas asked him to take over Douglas' epic production Spartacus (1960) from Anthony Mann, who had been fired by the studio two weeks into shooting.

Based upon the true story of a doomed uprising of Roman slaves, Spartacus was a difficult production. Creative differences arose between Kubrick and Douglas, and the two reportedly had a stormy working relationship. Frustrated by his lack of creative control, Kubrick later largely disowned the film, which further angered Douglas.[31] The friendship the two men had formed on Paths of Glory was destroyed by the experience of making the film. Years later, Douglas referred to Kubrick as "a talented shit."[32]

Despite the on-set troubles, Spartacus was a critical and commercial success and established Kubrick as a major director. However, its embattled production convinced Kubrick to find ways of working with Hollywood financing while remaining independent of its production system, which he called "film by fiat, film by frenzy."[33]

Spartacus is the only Stanley Kubrick film in which Kubrick had no hand in the screenplay,[34] no final cut,[35] no producing credit, or any say in the casting.[36][37][38][39] It was largely Kirk Douglas's project.

Spartacus would go on to win 4 Oscars with one going to Peter Ustinov, for his turn as the slave dealer Batiatus, the only actor to win one under Kubrick's direction.

In 1962, Kubrick moved to England to film Lolita, and he would live there for the rest of his life. The original motivation was to film Lolita in a country with laxer censorship laws. However, Kubrick had to remain in England to film Dr. Strangelove since Peter Sellers was not permitted to leave England at the time as he was involved in divorce proceedings, and the filming of 2001: A Space Odyssey required the large capacity of the sound stages of Shepperton Studios, which were not available in America. It was after filming the first two of these films in England and in the early planning stages of 2001 that Kubrick decided to settle in England permanently.

An editor has nominated the above file for discussion of its purpose and/or potential deletion. You are welcome to participate in the discussion and help reach a consensus.

Lolita was Kubrick's first film to generate major controversy.[41] The book, by Russian-American novelist Vladimir Nabokov, had been one of most controversial novels of the century, already notorious as an "obscene" novel and a cause célèbre, given its theme[42], when Kubrick embarked on the project. It dealt with an affair between a middle-aged professor named Humbert Humbert (James Mason) and his twelve-year-old stepdaughter. The difficult subject matter was mocked in the film's famous tagline, "How did they ever make a film of Lolita?"[43] Kubrick originally engaged Nabokov to adapt his own novel for the screen. The writer first produced a 400-page screenplay, which he then reduced to 200.[44] The final screenplay was written by Kubrick himself, and Nabokov himself estimated that only 20% of his work made it into the film.[45] The shorter version of Nabokov's original draft was later published under the title Lolita: A Screenplay.

Prior to its release, Kubrick realized that to get a Production Code seal, the screenplay would have to downplay the book's provocativeness, treading lightly with its theme. Kubrick tried to make some elements more acceptable by omitting all material referring to Humbert's lifelong infatuation with "nymphets" and possibly ensuring Lolita looked like a teenager. James Harris, Kubrick's co-producer and uncredited co-screenwriter of Lolita decided with Kubrick to raise Lolita's age.[46][47] Nonetheless, Kubrick had liaised with the censors during production and it was only "slightly edited", in particular removing the eroticism between Lolita and Humbert.[48] As a result, the novel's more sensual aspects were toned down in the final cut, leaving much to the viewer's imagination. Kubrick would later say that had he known the severity of the censorship he would face, he probably would not have made the film.[49]

Lolita was the first of two times Kubrick worked with British comic actor Peter Sellers, the second being Dr. Strangelove (1964). Sellers plays Clare Quilty, a second older man (unknown to Humbert) who is involved with Lolita, serving dramatically as Humbert's darker doppelganger. In the novel, Quilty is behind the scenes for most of the story, but Kubrick brings him to the foreground, which resulted in an expansion of his role (although it is only about thirty minutes of screen time). Kubrick exercised his dramatic license, and had Quilty pretend to be multiple characters in the film, allowing Sellers to employ his gift for mock accents.

Critical reception of the film was mixed; many praised it for its daring subject matter, while others were surprised by the lack of intimacy between Lolita and Humbert. Andrew Sarris panned it in The Village Voice for being too restrained and being miscast,[50] and it was panned in London's The Observer and by Eric Rhode on BBC Television News.[51] The film was heavily praised by Pauline Kael in The New Yorker though she later became one of Kubrick's greatest detractors. Recent reviews of the film in conjunction with its DVD release have been overwhelmingly positive. The film received an Academy Award nomination for Best Adapted Screenplay, and Sue Lyon, who played the title role, won a Golden Globe for Best Newcomer.

Film critic Gene Youngblood holds that stylistically Lolita is a transitional film for Kubrick, "marking the turning point from a naturalistic cinema...to the surrealism of the later films."[52]

Kubrick's next film, Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), became a cult film and is now considered a classic. Roger Ebert wrote that it is the best satirical film ever made.[53] The screenplay—based upon the novel Red Alert, by ex-RAF flight lieutenant Peter George (writing as Peter Bryant)—was co-written by Kubrick and George, with contributions by American satirist Terry Southern. Red Alert is a serious, cautionary tale of accidental atomic war. However, Kubrick found the conditions leading to nuclear war so absurd that the story became a sinister macabre comedy.[54] Once re-conceived, Kubrick recruited Terry Southern to polish the final screenplay.

The story centers on an unauthorized American nuclear attack on the Soviet Union, initiated by renegade U.S.A.F. Gen. Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden; the character's name is a reference to Jack the Ripper). When Ripper gives his orders, the bombers are all at fail-safe points, before which passing they cannot arm their warheads, and past which, they cannot proceed without direct orders. Once past this point, the planes will only return with a prearranged recall code. The film intercuts between three locales: Ripper's Air Force Base, where RAF Group Captain Lionel Mandrake (Sellers) tries to stop the mad Gen. Ripper by obtaining the codes; the Pentagon War Room, where the President of the United States (Sellers) and U.S.A.F. Gen. Buck Turgidson (George C. Scott) try to develop a strategy with the Soviets to stop Gen. Ripper's B-52 bombers from dropping nuclear bombs on Russia; and Major Kong's (Slim Pickens) B-52 bomber, where he and his crew of airmen (never knowing their orders are false) doggedly try to complete their mission. It soon becomes clear that the bombers may reach Russia, since only Gen. Ripper knows the recall codes. At this point, the character of Dr. Strangelove (Sellers' third role) is introduced. His Nazi-style plans for ensuring the survival of the fittest of the human race in the aftermath of a nuclear holocaust are the black-comedy highlight of the film.

Peter Sellers, who had played a pivotal part in Lolita and had appeared in several previous films in multiple roles, was hired to play four roles in Dr. Strangelove. He eventually played three, due to an injured leg and his difficulty in mastering bomber pilot Major "King" Kong's Texas accent. Kubrick later called Sellers "amazing", but lamented the fact that the actor's manic energy rarely lasted beyond two or three takes. Kubrick ran two cameras simultaneously and allowed Sellers to improvise, as he had earlier on the set of Lolita.[56]

Although, Peter Sellers would later become an international star after the release of his subsequent Pink Panther films and What's New Pussycat, at the time Doctor Strangelove was released Peter Sellers was still mainly a British comedy actor, relatively unknown in the United States. Although this was the sixth film with Peter Sellers in multiple roles, most American viewers did not initially realize that Kubrick had cast him in three roles, all with distinctively different appearances, accents, and personalities.[57] Dr. Strangelove is a manic German mad scientist, while the bald President of the United States is a mild-mannered model of sanity (the "straight man" of the comedy) with an American MidWestern accent, and Lional Mandrake is a stiff and stuffy mustached British officer.[58]

The film prefigured the antiwar sentiments which would become explosive only a few years after its release. It was highly irreverent toward war policies of the U.S., which were largely considered sacrosanct up to that time. Eight months after the release of Strangelove, the straight thriller Fail-Safe with a plot remarkably similar to that of Dr. Strangelove was released. Strangelove earned four Academy Award nominations (including Best Picture and Best Director) and the New York Film Critics' Best Director award.

Kubrick spent five years developing his next film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The film was conceived as a Cinerama spectacle and was photographed in Super Panavision 70. Kubrick co-wrote the screenplay with science fiction writer Sir Arthur C. Clarke, expanding on Clarke's short story "The Sentinel". Kubrick reportedly told Clarke that his intention was to make "the proverbial great science fiction film."

2001 begins four million years ago with an encounter between a group of apes and a mysterious black monolith, which seems to trigger in them the ability to use a bone as both a tool and a weapon. This new knowledge allows them to reclaim a water hole from another group of apes, who have no tool-wielding ability. A victorious ape tosses his bone into the air, at which point the film makes a celebrated match-cut to an orbiting satellite, circa 2000. At this time, a group of Americans at their moon base dig up a monolith similar to that encountered by the apes, which sends a radio signal to Jupiter. Eighteen months later, a group of astronauts aboard the spaceship Discovery are sent to explore Jupiter, their true purpose of investigating the signal is initially concealed from them. During the flight, the ship's sentient HAL 9000 computer, aware of the truth about the mission, malfunctions but resists disconnection. Believing its control of the mission to be crucial, the computer terminates life support for most of the crew before it is shut down by the surviving astronaut, David Bowman (Keir Dullea). Using a space pod, Bowman explores another monolith in orbit around Jupiter, whereupon he is hurled into a portal in space at high speed, witnessing many strange cosmological phenomena. His interstellar journey ends with his transformation into a fetus-like new being enclosed in an orb of light, last seen gazing at Earth from space.

The $10,000,000 (U.S.) film was a massive production for its time. The groundbreaking visual effects were overseen by Kubrick and were engineered by a team that included a young Douglas Trumbull, who would become famous in his own right for his work on the films Silent Running and Blade Runner. Kubrick extensively used traveling matte photography to film space flight, a technique also used nine years later by George Lucas in making Star Wars, although that film also used motion-control effects that were unavailable to Kubrick at the time. Kubrick made innovative use of slit-scan photography to film the Stargate sequence. The film's striking cinematography was the work of legendary British director of photography Geoffrey Unsworth, who would later photograph classic films such as Cabaret and Superman. Manufacturing companies were consulted as to what the design of both special-purpose and everyday objects would look like in the future. In a filmed press conference before the Los Angeles premiere of the film, later released as a DVD extra, Arthur C. Clarke predicted that a generation of engineers would design real spacecraft based upon 2001 "...even if it isn't the best way to do it." The film also is a rare instance of portraying space travel realistically, with complete silence in the vacuum of space and a realistic representation of weightlessness.

The film is famous for using classical music in place of an original score. Richard Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra and Johann Strauss's The Blue Danube waltz became indelibly associated with the film for a while, especially the former, as it was not well-known to the public prior to the film. Kubrick also used music by contemporary avant-garde Hungarian composer György Ligeti, although some of the pieces were altered without Ligeti's consent. The appearance of Atmospheres, Lux Aeterna, and Requiem on the 2001 soundtrack was the first wide commercial exposure of Ligeti's work. This use of "program" music was not originally planned. Kubrick had commissioned composer Alex North to write a full-length score for the film, but Kubrick became so attached to the temporary soundtrack he had constructed during editing that he dropped the idea of an original score entirely.[59]

Although it eventually became an enormous success, the film was not an immediate hit. Initial critical reaction was extremely hostile, with critics attacking the film's lack of dialogue, slow pacing, and seemingly impenetrable storyline. One of the film's few defenders was Penelope Gilliatt,[60] who called it (in The New Yorker) "some kind of a great film". Word of mouth among young audiences—especially the 1960s counterculture audience, who loved the movie's "Star Gate" sequence, a seemingly psychedelic journey to the infinite reaches of the cosmos—made the film a hit. Despite nominations in the directing, writing, and producing categories, the only Academy Award Kubrick ever received was for supervising the special effects of 2001: A Space Odyssey. Today, however, many consider it the greatest sci-fi film ever made,[61] and it is a staple on All Time Top 10 lists.[62]

Artistically, 2001 was a radical departure from Kubrick's previous films. It contains only 45 minutes of spoken dialogue, over a running time of two hours and twenty minutes. The fairly mundane dialogue is mostly superfluous to the images and music. The film's most memorable dialogue belongs to the computer HAL in HAL's exchanges with Dave Bowman. Some argue that Kubrick is portraying a future humanity largely dissociated from a sterile and antiseptic machine-driven environment.[63][64][65][66] The film's ambiguous, perplexing ending continues to fascinate contemporary audiences and critics. After this film, Kubrick would never experiment so radically with special effects or narrative form; however, his subsequent films would still maintain some level of ambiguity.

Interpretations of 2001: A Space Odyssey are numerous and diverse. Despite having been released in 1968, it still prompts debate today. When critic Joseph Gelmis asked Kubrick about the meaning of the film, Kubrick replied:[67]

They are the areas I prefer not to discuss, because they are highly subjective and will differ from viewer to viewer. In this sense, the film becomes anything the viewer sees in it. If the film stirs the emotions and penetrates the subconscious of the viewer, if it stimulates, however inchoately, his mythological and religious yearnings and impulses, then it has succeeded.

2001: A Space Odyssey is perhaps Kubrick's most famous and influential film. Steven Spielberg called it his generation's big bang,[68] focusing attention upon the space race. It was a precursor to the explosion of the science fiction film market nine years later, which began with the release of Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind.

1970s: A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon

After 2001, Kubrick initially attempted to make a film about the life of Napoleon Bonaparte. When financing fell through, Kubrick went looking for a project that he could film quickly on a small budget. He eventually settled on A Clockwork Orange (1971). His adaptation of Anthony Burgess' novel is a dark, shocking exploration of violence in human society. The film was initially released with an X rating in the United States[69] and caused considerable controversy. The film's iconic poster imagery was created by legendary designer Bill Gold.

The story takes place in a futuristic version of Great Britain that is both authoritarian and chaotic. The central character is a teenage hooligan named Alex DeLarge (Malcolm McDowell), who, along with his companion "droogs", gleefully torments, beats, robs, tortures, and rapes without conscience or remorse. His brutal beating and murder of an older woman finally lands Alex in prison. Alex undergoes an experimental medical aversion treatment, known as the Ludovico Technique, that inhibits his violent tendencies, though he has no real free moral choice. At the public demonstration of the success of the technique, Alex is treated cruelly but does not fight back; the treatment has made him less than human. He has been conditioned against classical music, his love of which was his one human feature, and apparently all of his sex drive is gone. We further see hints that the promotion of the treatment is politically motivated. After being freed, he is found by his former partners in crime who had betrayed him and who are now policemen, and they beat him mercilessly.

He then comes to the home of a political writer who disdains "the modern age" and is initially sympathetic to Alex's plight until he recognizes Alex as the young man who brutally raped his wife and paralyzed him a few years before. Alex then becomes a pawn in a political game.

The society was sometimes perceived as Communist (as Michel Ciment pointed out in an interview with Kubrick, although he himself did not feel that way) due to its slight ties to Russian culture. The teenage slang has a heavily Russian vocabulary, which can be attributed to Burgess. There is some evidence to suggest that the society is a socialist one, or perhaps a society moving out of a failed, Leftist socialism and into a Rightist, or fascist, society. In the novel, streets have paintings of working men in the style of Russian socialist art, and in the film, there is a mural of socialist artwork with obscenities drawn on it. As Malcolm McDowell points out on the DVD commentary, Alex's residence was shot on failed Labour Party architecture, and the name "Municipal Flat Block 18A, Linear North" alludes to socialist-style housing. Later in the film, when the new right-wing government takes power, the atmosphere is certainly more authoritarian than the anarchist air of the beginning. Kubrick's response to Ciment's question remained ambiguous as to exactly what kind of society it is. He held that the film held comparisons between both the left and right end of the political spectrum and that there is little difference between the two. Kubrick stated, "The Minister, played by Anthony Sharp, is clearly a figure of the Right. The writer, Patrick Magee, is a lunatic of the Left...They differ only in their dogma. Their means and ends are hardly distinguishable."[70]

Kubrick photographed A Clockwork Orange quickly and almost entirely on location in and around London. Despite the low-tech nature of the film as compared to 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick showed his talent for innovation; at one point, he threw "an old Newman Sinclair clockwork mechanism camera" off a rooftop in order to achieve the effect he wanted.[71] For the score, Kubrick enlisted electronic music composer Wendy Carlos—at the time, known as Walter Carlos (Switched-On Bach)—to adapt famous classical works (such as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony) for the Moog synthesizer.

It is pivotal to the plot that the lead character, Alex, is fond of classical music, and that the brainwashing Ludovico treatment accidentally conditions him against classical music. As such, it was natural for Kubrick to continue the tradition begun in 2001: A Space Odyssey of using a great deal of classical music in the score. However, in this film, classical music accompanies scenes of violent mayhem and coercive sexuality rather than of graceful space flight and mysterious alien presences. Both Pauline Kael (who generally disliked Kubrick's work after Lolita) and Roger Ebert (who often praises Kubrick) found Kubrick's use of juxtaposing classical music and violence in this film unpleasant, Ebert calling it a "cute, cheap, dead-end dimension,"[72] and Kael, "self-important."[73] Burgess, in his introduction to his own stage adaptation of the novel, held that ultimately, classical music is what will finally redeem Alex.

The film was extremely controversial because of its explicit depiction of teenage gang rape and violence. It was released in the same year as Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs and Don Siegel's Dirty Harry, and the three films sparked a ferocious debate in the media about the social effects of cinematic violence. The controversy was exacerbated when copycat crimes were committed in England by criminals wearing the same costumes as characters in A Clockwork Orange. British readers of the novel noted that Kubrick had omitted the final chapter (also omitted from American editions of the book) in which Alex finds redemption and sanity.

After receiving death threats to himself and his family as a result of the controversy, Kubrick took the unusual step of removing the film from circulation in Britain. It was unavailable in the United Kingdom until its re-release in 2000, a year after Kubrick's death, although it could be seen in continental Europe. The Scala cinema in London's Kings Cross showed the film in the early 1990s, and at Kubrick's insistence, the cinema was sued and put out of business, thus depriving London of one of its very few independent cinemas. It is now the Scala club.[74] In early 1973, Kubrick re-released A Clockwork Orange to cinemas in the United States with footage modified so that it could get its rating reduced to an R. This enabled many more newspapers to advertise it, since in 1972 many newspapers had stopped carrying any advertising for X-rated films due to the new association of that rating with pornography.[75]

In the mid-1990s, a documentary entitled Forbidden Fruit, about the censorship controversy, was released in Britain. Kubrick was unable to prevent the documentary makers from including footage from A Clockwork Orange in their film.

Kubrick's next film, released in 1975, was an adaptation of William Makepeace Thackeray's The Luck of Barry Lyndon, also known as Barry Lyndon, a picaresque novel about the adventures and misadventures of an 18th-century Irish gambler and social climber. After serving in the Prussian army, Lyndon slowly insinuates himself into English high society, eventually marrying the Countess of Lyndon. The world of the aristocracy turns out to be a hollow paradise, dull and decaying. Lyndon is ultimately unable to maintain his good standing there and falls from grace after a series of persecutions.

Reviewers such as Pauline Kael, who had been critical of Kubrick's previous work,[73] found Barry Lyndon a cold, slow-moving, and lifeless film. Its measured pace and length—more than three hours—put off many American critics and audiences, although it received positive reviews from Rex Reed and Richard Schickel. Time magazine published a cover story about the film, and Kubrick was nominated for three Academy Awards. The film as a whole was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won four, more than any other Kubrick film. Despite this, Barry Lyndon was not a box office success in the U.S., although the film found a great audience in Europe, particularly in France. The French journal of film criticism, Cahiers du cinéma, included Barry Lyndon at 67 on its top 100 list of all-time films.[76]

As with most of Kubrick's films, Barry Lyndon's reputation has grown through the years, particularly among other filmmakers. Director Martin Scorsese has cited it as his favorite Kubrick film. Steven Spielberg has praised its "impeccable technique", though, when younger, he famously described it "like going through the Prado without lunch."[77]

As in his other films, Kubrick's cinematography and lighting techniques were highly innovative. Most famously, interior scenes were shot with a specially adapted high-speed f/0.7 Zeiss camera lens originally developed for NASA. This allowed many scenes to be lit only with candlelight, creating two-dimensional diffused-light images reminiscent of 18th-century paintings.[78]

Like its two predecessors, the film does not have an original score. Irish traditional songs (performed by The Chieftains) are combined with works such as Antonio Vivaldi's Cello Concerto in B, a Johann Sebastian Bach Double Concerto, George Frideric Handel's Sarabande from the Keyboard Suite in D minor (HWV 448, HG II/ii/4), and Franz Schubert's German Dance No. 1 in C major, Piano Trio No. 2 in E flat, and Impromptu No. 1 in C minor. The music was conducted and adapted by Leonard Rosenman, for which he won an Oscar.

In 1976, production designer Ken Adam, who had worked with Kubrick on Dr. Strangelove and Barry Lyndon, asked Kubrick to visit the recently completed 007 Stage at Pinewood Studios to provide advice on how to light the enormous soundstage, which had been built and prepared for the James Bond movie The Spy Who Loved Me. Kubrick agreed to consult when it was promised that nobody would ever know of his involvement. This was honored until after his death in 1999, when in 2000 the fact was revealed by Adam in the documentary on the making of The Spy Who Loved Me on the special edition DVD release of the movie.

1980s: The Shining and Full Metal Jacket

The pace of Kubrick's work slowed considerably after Barry Lyndon, and he did not make another film for five years. The Shining, released in 1980, was adapted from the novel of the same name by bestselling horror writer Stephen King. The film starred Jack Nicholson as Jack Torrance, a failed writer who takes a job as an off-season caretaker of the Overlook Hotel, a high-class resort deep in the Colorado mountains. The job requires spending the winter in the isolated hotel with his wife, Wendy (played by Shelley Duvall) and their young son, Danny (played by Danny Lloyd), who is gifted with a form of telepathy—the "shining" of the film's title.

As winter takes hold, the family's isolation deepens, and the demons and ghosts of the Overlook Hotel's dark past begin to awake, displaying horrible, phantasmagoric images to Danny, and driving his father Jack into a homicidal psychosis.

The film was shot entirely on London soundstages, with the exception of second-unit exterior footage, which was filmed in Colorado, Montana, and Oregon. In order to convey the claustrophobic oppression of the haunted hotel, Kubrick made extensive use of the newly invented Steadicam, a weight-balanced camera support, which allowed for smooth camera movement in enclosed spaces. Although used for a few scenes in a few previous motion pictures, the inventor of the Steadicam, Garrett Brown, was closely involved with this production and regarded it as the first picture to fully employ the new camera's potential.[79]

More than any of his other films, The Shining gave rise to the legend of Kubrick as a megalomaniac perfectionist. Reportedly, he demanded hundreds of takes of certain scenes (approximately 1.3 million feet of film was shot). This process was particularly difficult for actress Shelley Duvall, who was used to the faster, improvisational style of director Robert Altman.

Stephen King disliked the movie, calling Kubrick "a man who thinks too much and feels too little."[80] In 1997, King collaborated with Mick Garris to create a television miniseries version of the novel that was more faithful to King's original.

The film opened to mixed reviews, but proved a commercial success. As with most Kubrick films, subsequent critical reaction has treated the film more favorably. Among horror movie fans, The Shining is a cult classic, often appearing at the top of best horror film lists alongside Psycho (1960), The Exorcist (1973), and other horror classics. Much of its imagery, such as the elevator shaft disgorging blood and the ghost girls in the hallway are among the most recognizable and widely known images from any Stanley Kubrick film, as are the lines "Redrum" and "All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy" as well as "Here's Johnny!". The financial success of The Shining renewed Warner Brothers' faith in Kubrick's ability to make artistically satisfying and profitable films after the commercial failure of Barry Lyndon in the United States.

Seven years later, Kubrick made his next film, Full Metal Jacket (1987), an adaptation of Gustav Hasford's Vietnam War novel The Short-Timers, starring Matthew Modine as Joker, Adam Baldwin as Animal Mother, R. Lee Ermey as Gunnery Sergeant Hartman, and Vincent D'Onofrio as Private Leonard "Gomer Pyle" Lawrence. Kubrick said to film critic Steven Hall that his attraction to Gustav Hasford's book was because it was "neither antiwar or prowar", held "no moral or political position", and was primarily concerned with "the way things are."

The film begins at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina, U.S., where Senior Drill Instructor Gunnery Sergeant Hartman relentlessly pushes his recruits through basic training in order to transform them from worthless "maggots" into motivated and disciplined killing machines. Private Lawrence, an overweight, slow-witted recruit who Hartman has nicknamed "Gomer Pyle", is unable to cope with the program and slowly cracks under the strain. On the eve of graduation, he has a psychotic breakdown and murders Hartman before killing himself.

In characteristic Kubrick style, the second half of the film jumps abruptly to Vietnam, following Joker, since promoted to sergeant. As a reporter for the United States military's newspaper, Stars and Stripes, Joker occupies war's middle ground, using wit and sarcasm to detach himself from the carnage around him. Though a Marine at war, he is also a reporter and is thus compelled to abide by the ethics of his profession. The film then follows an infantry platoon's advance on and through Hue City, decimated by the Tet Offensive. The film climaxes in a battle between Joker's platoon and a sniper hiding in the rubble, who is revealed to be a young girl. She almost kills Joker until his reporter partner shoots and severely injures her. Joker then kills her to put her out of her misery.

Filming a Vietnam War film in England was a considerable challenge for Kubrick and his production team. Much of the filming was done in the Docklands area of London, with the ruined-city set created by production designer Anton Furst. As a result, the film is visually very different from other Vietnam War films such as Platoon and Hamburger Hill, most of which were shot in the Far East. Instead of a tropical, Southeast-Asian jungle, the second half of the story unfolds in a city, illuminating the urban warfare aspect of a war generally portrayed (and thus perceived) as jungle warfare, notwithstanding significant urban skirmishes like the Tet offensive. As actor Adam Baldwin put it "When you think of Vietnam, its natural to imagine jungles. But this story is about urban warfare".[81] Reviewers and commentators thought this contributed to the bleakness and seriousness of the film.[82] During the making of the film, Kubrick was also helped by R. Lee Ermey, who acted and worked as technical adviser.[83][84]

Full Metal Jacket received mixed critical reviews on release but also found a reasonably large audience, despite being overshadowed by Oliver Stone's Platoon and Clint Eastwood's Heartbreak Ridge. Like Kubrick's other films, its critical status has increased immensely since its initial release.

1990s: Eyes Wide Shut

Kubrick's final film was Eyes Wide Shut, starring then-married actors Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as a wealthy Manhattan couple on a sexual odyssey.

The story of Eyes Wide Shut is based on Arthur Schnitzler's Freudian novella Traumnovelle (Dream Story in English), although the story has been moved from Vienna in the 1920s to New York City in the 1990s. It follows Dr. William Harford's journey into the sexual underworld of New York City, after his wife, Alice, has shattered his faith in her fidelity by confessing to having fantasized about giving him and their daughter up for one night with another man. Until then, Harford had presumed women are more naturally faithful than men. This new revelation generates doubt and despair, and he begins to roam the streets of New York, acting blindly on his jealousy.

After trespassing upon the rituals of a sinister, mysterious sexual cult, Dr. Harford thinks twice before seeking sexual revenge against his wife. Upon returning home, his wife now gives an anguished confession she has had a dream about making love to several men at once. After his own dangerous escapades, Dr. Harford has no high moral ground over her. The couple begin to patch their relationship.

The film was in production for more than two years, and two of the main members of the cast, Harvey Keitel and Jennifer Jason Leigh, were replaced in the course of the filming. Although it is set in New York City, the film was mostly shot on London soundstages, with little location shooting. Shots of Manhattan itself were pickup shots filmed in New York City by a second-unit crew. Because of Kubrick's secrecy about the film, mostly inaccurate rumors abounded about its plot and content. Most especially, the story's sexual content provoked speculation, some journalists writing that it would be "the sexiest film ever made."[85] The casting of then celebrity-actor supercouple Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as a husband-wife couple in the film along with Kubrick's characteristic secrecy increased the pre-release journalistic hyperbole.[86][87]

Eyes Wide Shut, like Lolita and A Clockwork Orange before it, faced censorship before release. In the United States and Canada, digitally manufactured silhouette figures were strategically placed to mask explicit copulation scenes so as to secure an R rating from the MPAA. In Europe, and the rest of the world, the film has been released uncut, in its original form. The October 2007 DVD reissue contains the uncut version, making it available to North American audiences for the first time.

Death

In 1999—four days after screening a final cut of Eyes Wide Shut for his family, Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman, and Warner Bros. executives—70-year-old Kubrick died of a heart attack in his sleep. He was buried next to his favorite tree in Childwickbury Manor, Hertfordshire, England, U.K.[88]

Following his death, several directors and actors discussed their experiences with Kubrick. Steven Spielberg said in a 1999 interview about how Dr. Strangelove made him forget about being drafted into the Army.[89]

Projects completed by others

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

Throughout the 1980s and early '90s, Kubrick collaborated with Brian Aldiss on an expansion of his short story "Super-Toys Last All Summer Long" into a three-act film, along with other writers, such as Sara Maitland and Ian Watson, under various names, including "Pinocchio" and "Artificial Intelligence". It was a futuristic fairy-tale about a robot that resembles and behaves as a child, sold as a temporary surrogate to a family whose real son is in suspended animation with a deadly disease. The story focuses on the efforts of the robot to become a 'real boy' in a manner similar to Pinocchio.

Kubrick reportedly held long telephone discussions with Steven Spielberg regarding the film, and, according to Spielberg, at one point stated that the subject matter was closer to Spielberg's sensibilities than his.[90] In 1999, following Kubrick's death, Spielberg took the various drafts and notes left by Kubrick and his writers and composed a new screenplay and, in association with what remained of Kubrick's production unit, made the movie A.I. Artificial Intelligence, starring Haley Joel Osment, Jude Law, Frances O'Connor, and William Hurt.[91] The film was released in June 2001.

The film contains a posthumous producing credit for Stanley Kubrick at the beginning and the brief dedication "For Stanley Kubrick" at the end. The film contains many recurrent Kubrick motifs, such as an omniscient narrator, an extreme form of the three-act structure, the themes of humanity and inhumanity, and a sardonic view of Freudian psychology. In addition, John Williams' score contains many allusions to pieces heard in other Kubrick films.[92]

Many critics found the film to be a peculiar merging of the disparate sensibilities of Stanley Kubrick and Stephen Spielberg. In a mostly positive review, Tim Merrill wrote

Finally, Steven Spielberg has made a film that is not for everyone. And we have Stanley Kubrick’s ghost to thank for it. Let’s also pause for a moment to consider how unique is this union of two legendary directors: the Eccentric Recluse meets the King of Hollywood. Spielberg and Kubrick, two filmmakers whose styles and sensibilities stand diametrically opposed, are master technicians with vastly different notions about the nature of humanity.[93]

One-Eyed Jacks

The Hollywood Reporter announced on October 18, 1956 that producer Frank Rosenberg had bought rights to Charles Neider's novel The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones for $40,000. Two years later, Pennebaker Inc., Marlon Brando's independent production company, bought the rights to the novel as well as Sam Peckinpah's first-draft screenplay adaptation for $150,000. Even at this time, it was announced that Brando might direct.

Later that year, Kubrick was announced as director of Gun's Up, the working title for the production. Shortly after this announcement, the name of the film was changed to One-Eyed Jacks and Pina Pellicer was announced as "the unanimous choice of Brando, Rosenberg, and Kubrick" to play the female lead.

On November 20, 1958, Kubrick quit as director of One-Eyed Jacks, stating that he had the utmost respect for Marlon Brando as one of "the world's foremost artists"[94] but had recently acquired the rights to Nabokov's Lolita and wanted to begin production work immediately in light of this wonderful opportunity. Speaking more candidly in a 1960 interview Kubrick stated, "When I left Brando's picture, it still didn't have a finished script. It had just become obvious to me that Brando wanted to direct the movie. I was just sort of playing wingman for Brando, to see that nobody shot him down."[95] The film was completed with directorial credit given to Marlon Brando.

Unrealized projects

Frequent collaborators

Unlike directors such as John Ford, Martin Scorsese, and Akira Kurosawa, Kubrick did not generally reuse actors. However, Kubrick did on several occasions work with the same actor more than once. In lead roles, Sterling Hayden appeared in both The Killing and Dr. Strangelove, Peter Sellers in Lolita and Dr. Strangelove, and Kirk Douglas in Paths of Glory and Spartacus. In supporting roles, Joe Turkel appears in The Killing, Paths of Glory, and The Shining, Philip Stone appears in A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, and The Shining, Leonard Rossiter is featured in 2001: A Space Odyssey and Barry Lyndon, while Timothy Carey is in both The Killing and Paths of Glory. A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon saw the largest crossover, with six actors (including Patrick Magee) having roles of various lengths in each film.

One of Kubrick's longest collaborations was with Leon Vitali, who, after playing the older Lord Bullingdon in Barry Lyndon, became Kubrick's personal assistant, working as the casting director on his following films, and supervising film-to-video transfers for Kubrick.[96] He also appeared in Eyes Wide Shut, playing the ominous Red Cloak, who confronts Tom Cruise during the infamous orgy scene. Since Kubrick's death, Vitali has overseen the restoration of both picture and sound elements for most of Kubrick's films. He has also collaborated frequently with Eyes Wide Shut co-star Todd Field on his pictures.

Family cameos

Stanley Kubrick's daughter Vivian has cameos in 2001: A Space Odyssey (as Heywood Floyd's daughter), Barry Lyndon (as a girl at the birthday party for young Bryan Lyndon), The Shining (as a party ghost), and Full Metal Jacket (as a TV reporter). His stepdaughter Katharina has cameos in A Clockwork Orange and Eyes Wide Shut, and her character's son in the latter is played by her real son. Kubrick's wife Christiane Kubrick appeared prior to her marriage to Kubrick in Paths of Glory, billed as Susanne Christian (her birth name is Christiane Susanne Harlan), and as a cafe guest in Eyes Wide Shut.

Trademark characteristics

Stanley Kubrick's films have several trademark characteristics. All but his first two full-length films and 2001 were adapted from existing novels (2001 being based on The Sentinel as well as having its own planned novelization), and he occasionally wrote screenplays in collaboration with writers (usually novelists, but a journalist in the case of Full Metal Jacket) who had limited screenwriting experience.[97] Many of his films had voice-over narration, sometimes taken verbatim from the novel. With or without narration, all of his films contain extensive character's-point-of-view footage. The closing of films with "The End" went out of style in the wake of the advent of long closing credits in the 1970s. (Disney films, for example, stopped using "The End" in 1984). However, Kubrick continued to put it at the end of the credits in every one of his films, long after the rest of the film industry stopped using it. On the other hand, Kubrick occasionally dispensed with opening credits (in A Space Odyssey and A Clockwork Orange) as had Orson Welles in Citizen Kane and Walt Disney in Fantasia before him and George Lucas and Francis Coppola would do subsequently. Kubrick's credits are always a slide show. His only rolling credits are the opening credits to The Shining.

Kubrick paid close attention to the releases of his films in other countries. Not only did he have complete control of the dubbing cast, but sometimes alternative material was shot for international releases—in The Shining, the text on the typewriter pages was re-shot for the countries in which the film was released[98]; in Eyes Wide Shut, the newspaper headlines and paper notes were re-shot for different languages[99]. Kubrick always personally supervised the foreign voice-dubbing and the actual script translation into foreign languages for all of his films[99]. Since Kubrick's death, no new voice translations have been produced for any of the films he had control of; in countries where no authorized dubs exist, only subtitles are used for translation.

Beginning with 2001: A Space Odyssey, all of his films except Full Metal Jacket used mostly pre-recorded classical music, in two cases electronically altered by Wendy Carlos.[100] He also often used merry-sounding pop music in an ironic way during scenes depicting devastation and destruction, especially in the closing credits or end sequences of a film.[101]

In his review of Full Metal Jacket, Roger Ebert[102] noted that many Kubrick films have a facial closeup of an unraveling character in which the character's head is tilted down and his eyes are tilted up, although Ebert does not think there is any deep meaning to these shots. Lobrutto's biography of Kubrick notes that his director of photography, Doug Milsome, coined the phrase the "Kubrick crazy stare". Kubrick also extensively employed wide angle shots, character tracking shots, zoom shots, and shots down tall parallel walls.

Critic and Kubrick biographer Alexander Walker has noted Kubrick's repeated "corridor" compositions,[103] of which two particularly well-known ones are the StarGate sequence in 2001: A Space Odyssey and the extensive use of the hotel corridors in The Shining.

Many of Kubrick's films have back-references to previous Kubrick films. The best-known examples of this are the appearance of the soundtrack album for 2001: A Space Odyssey appearing in the record store in A Clockwork Orange and Quilty's joke about Spartacus in Lolita. Less obvious is the reference to a painter named Ludovico in Barry Lyndon, Ludovico being the name of the conditioning treatment in A Clockwork Orange[104].

Almost all Stanley Kubrick movies have a scene in or just outside a bathroom[105] (The more frequently cited example of this in 2001 is Dr. Floyd's becoming stymied by the Zero-Gravity Toilet en route to the moon, rather than David Bowman's exploration [while still wearing his spacesuit] of the bathroom adjacent to his celestial bedroom after his journey through the StarGate).[106]

CRM-114

Although Dr. Strangelove employs a device called CRM-114, and A Clockwork Orange has a sound-alike medicine called Serum 114, numerous and oft-repeated claims that the numbers 114 appear in other Kubrick films are apocryphal. CRM-114 is also used in the source novel Red Alert, upon which Dr. Strangelove is based, although claims have been made that the acronym appears in Kubrick's earlier film The Killing. Nonetheless, in a remarkable case of a director's influence over popular culture through an exaggerated urban legend, there is in honor of this Kubrick trademark, an e-mail spam filtering system, a progressive rock band, a right-wing website, a sound amplifier in the film Back to the Future, a catalog code in the TV series Heroes, and a weapon in the TV series Star Trek: Deep Space Nine, all named CRM-114, as well as a short film called Serum 114. The Star Trek: Deep Space Nine episode, "Business as Usual", had as guest star actor Steven Berkoff from A Clockwork Orange and Barry Lyndon, and it was directed by regular cast member Alexander Siddig, who is a nephew of A Clockwork Orange star Malcolm McDowell.[107]

Aspect ratio

There has been a longstanding debate regarding the DVD releases of Kubrick's films, specifically regarding the aspect ratio of many of the films. The primary point of contention relates to his final five films: A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut.

Kubrick's initial involvement with home video mastering of his films was a result of television screenings of 2001: A Space Odyssey.[108] Because the film was shot in 65 mm, the composition of each shot was compromised by the pan-and-scan method of transferring a wide-screen image to fit a 1.33:1 television set.

Kubrick's final five films were shot "flat"—the full 1.37:1 area is exposed in the camera, but with appropriate markings on the viewfinder, the picture was composed for and cropped to the 1.85:1 aspect ratio in a theater's projector.

The first mastering of these five films was in 2000 as part of the "Stanley Kubrick Collection", consisting of Lolita, Dr. Strangelove (in association with Sony Pictures), 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, Barry Lyndon, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut. Kubrick oversaw the video masters in 1989 for Warner Home Video, and approved of 1.33:1 transfers for all of the films except for 2001, which was letterboxed[citation needed].

Kubrick never approved a 1.85:1 video transfer of any of his films; when he died in 1999, DVDs and the 16:9 format were only beginning to become popular in the US. Most people were accustomed to seeing movies fill their television screen. Warner Home Video chose to release these films with the transfers that Kubrick had explicitly approved.[109]

In 2007, Warner Home Video remastered 2001: A Space Odyssey, A Clockwork Orange, The Shining, Full Metal Jacket, and Eyes Wide Shut in High-Definition, releasing the titles on DVD, HD DVD, and Blu-ray Disc. All were released in 16:9 anamorphic transfers, preserving the theatrical 1.85:1 aspect ratios for all of the flat films except A Clockwork Orange, which was transferred at the aspect ratio of 1.66:1.[110]

In regards to the Warner Bros. titles, there is little studio documentation that is public about them other than instructions given to projectionists on initial release; however, Kubrick's storyboards for The Shining do prove that he composed the film for wide-screen. In instructions given to photographer John Alcott in one panel, Kubrick writes: THE FRAME IS EXACTLY 1.85-1. Obviously you compose for that but protect the full 1.33-1 area.[111]

More confusion results regarding Kubrick's non-Warner distributed titles. During the days of laserdisc, The Criterion Collection released six Kubrick films. Spartacus and 2001 were both native 70 mm releases (exhibited in their roadshow engagements at a ratio of 2.20:1) at the same ratio as their subsequent DVD releases, and The Killing and Paths of Glory were both transferred at 1.33:1, despite the latter being hard matted extensively. Both pictures were theatrically projected at an aspect ratio of 1.85:1.[112][113]

Dr. Strangelove and Lolita were also transferred at 1.33:1, although Strangelove exhibits a number of hard mattes at a ratio of 1.66:1 in second-unit footage. This is sometimes falsely attributed to the use of stock footage in Strangelove. Both films were presented theatrically at ratios of 1.85:1.[114][115]

The DVD versions of The Killing and Paths of Glory released by MGM Home Entertainment retained the same 1.33:1 aspect ratio as the laserdisc versions. The Criterion Collection DVD and Blu-ray editions of The Killing and Paths of Glory feature a 1.66:1 aspect ratio.[116][117] The initial DVD releases of Strangelove maintained the 1.33:1, Kubrick-approved transfer, but for the most recent DVD and Blu-ray editions, Sony Pictures Home Entertainment replaced it with a new, digitally remastered anamorphic transfer with an aspect ratio of 1.66:1. All DVD and Blu-ray releases of Lolita to date have been at a uniform 1.66:1 aspect ratio. The Blu-ray edition of Barry Lyndon presents the film in a 1.78:1 aspect ratio.

Laserdisc releases of 2001 were presented in a slightly different aspect ratio than the original film. The film was shot in 65 mm, which has a ratio of 2.20:1, but many theaters could only show it in 35 mm reduction prints, which were presented at a ratio of 2.35:1. Thus, the picture was slightly modified for the 35 mm prints. The laserdisc releases maintained the 2.20:1 ratio, but the source material was an already cropped 35 mm print; thus, the edges were slightly cropped and the top and bottom of the image slightly opened up. This seems to have been corrected with the most recent DVD release, which was newly remastered from a 70 mm print.

Personal life and beliefs

Alternative adaptations

Three of Stanley Kubrick's films have had their source material re-adapted in some fashion: Anthony Burgess's subsequent stage adaptation of A Clockwork Orange in 1990, which he hoped would be considered a more definitive adaptation than Kubrick's film;[118] the Stephen King written and produced television miniseries of The Shining, which he hoped would stand as the authorized adaptation; and Adrian Lyne's adaptation of Lolita, which had the blessing of Vladimir Nabokov's son, Dmitri (who echoed his father's moderate misgivings about Kubrick's version).[119][120] Both Burgess and King overtly stated that they were annoyed by Kubrick's denying their lead characters (Alex DeLarge and Jack Torrance, respectively) a final redemption that was present in the source material, but absent from Kubrick's adaptation.

Influences

Alexander Walker in his book Stanley Kubrick Directs notes that Kubrick often mentioned Max Ophuls as an influence on his moving camera, especially the tracking shots in Paths of Glory.[103] Geoffrey Cocks sees the influence of Ophuls as going beyond this to include a sensibility drawn to stories of thwarted love and a preoccupation with predatory men.[121] Kubrick once named Ophul’s Le Plaisir his favorite film. A very young Jean-Luc-Godard in a (pejorative) review of The Killing also noted the influence of Ophuls on Kubrick's camera movements.

Critic Robert Kolker sees evident influence of Orson Welles on the same moving camera shots, while biographer Vincent LeBrutto states that Kubrick consciously identified with Welles.[122] LeBrutto sees much influence of Welles' style on Kubrick's The Killing, "the multiple points of view, extreme angles, and deep focus"[122] and on the style of the closing credits of Paths of Glory, and Quentin Curtis in The Daily Telegraph describes Welles as "[Kubrick's] great influence, in composition and camera movement."[123] One particular film of John Huston, The Asphalt Jungle, sufficiently impressed Kubrick as to persuade him he wanted to cast Sterling Hayden in his first major feature The Killing.[122]

Walker states that Kubrick never acknowledged Fritz Lang as an influence on him, but holds that Lang's interests are analogous to Kubrick's with regard to an interest in myth and "the Teutonic unconscious".[103]

As a young man, Kubrick also was fascinated by the films of Russian filmmakers such as Eisenstein and Pudovkin.[122] Kubrick also as a young man read Pudovkin’s seminal theoretical work, Film Technique which argues that editing makes film a unique art form, which needs to be effectively employed to manipulate the medium to its fullest. Kubrick recommended this work to others for years to come. Thomas Nelson describes this book as "the greatest influence of any single written work on the evolution of [Kubrick's] private aesthetics".[25]

Kubrick was also a great admirer of the films of Vittorio De Sica, Jean Renoir, Ingmar Bergman, and Federico Fellini, but the degree of their influence on his own style has not been assessed. In an early interview with Horizon magazine in the late 1950s, Kubrick stated, "I believe Ingmar Bergman, Vittorio De Sica and Federico Fellini are the only three filmmakers in the world who are not just artistic opportunists. By this I mean they don't just sit and wait for a good story to come along and then make it. They have a point of view which is expressed over and over and over again in their films, and they themselves write or have original material written for them."[124]

Late in life, Kubrick became enamored with the works of David Lynch, being particularly fascinated by Lynch's first major film Eraserhead,[125][126] which he asked cast members of The Shining to watch to establish the mood he wanted to convey.

Legacy

Kubrick made only thirteen feature films in his life. His oeuvre was comparatively low in number (compared to contemporaries such as Ingmar Bergman or Federico Fellini) due to his methodical and meticulous dedication to every aspect of film production. A number of his films are recognized as seminal classics within their genre.

One of the things that I always find extremely difficult, when a picture's finished, is when a writer or a film reviewer asks, Now, what is it that you were trying to say in that picture? And without being thought too presumptuous for using this analogy, I like to remember what T.S. Eliot said to someone who had asked him — I believe it was about The Waste Land — what he meant by the poem. He replied, I meant what it said. If I could have said it any differently, I would have.

Stanley Kubrick Interview with Horizon late 1950s reproduced in Entertainment Weekly Robert Emmett Ginna (Apr 09, 1999). "Stanley Kubrick speaks for himself". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 21 January 2011. {{cite web}}: Check date values in: |date= (help)

Awards and recognition

All Kubrick films from Paths of Glory to the end of his career were nominated for at least one Golden Globe or Oscar (along with several BAFTA nominations) with the notable exception of The Shining which is not only the least honored of Kubrick's films since 1956's The Killing, but was actually nominated for the infamous Razzie award. (However, this was the first year of the Razzies which at that time was run out of one person's home and was voted on by less than 10 people, rather than the large international committee that votes on it today.) Ironically, at least two published books, The Wolf at the Door by Jay Cocks and Kubrick, inside a film artist's maze by Thomas Nelson, consider The Shining to be a kind of master key to Kubrick's whole body of work in which all of Kubrick's philosophical preoccupations merge into a grand synthesis.

Six of Stanley Kubrick's films were nominated for Academy Awards in various categories, including acting Oscars for Spartacus. 2001: A Space Odyssey received numerous technical awards, including a BAFTA award for cinematographer Geoffrey Unsworth and an Academy Award for best visual effects, which Kubrick (as director of special effects on the film) received. This was Kubrick's only personal Oscar win among 13 nominations.

Most awards for which Kubrick's films were nominated tended to be in the areas of cinematography, art design, screenwriting, and music. For these, see articles on the individual films. However, only four of his films were nominated for their acting performances, notably Lolita, getting three acting nominations from the Golden Globes, and Peter Sellers getting nominated for both an Oscar and a BAFTA for his triple roles in Dr. Strangelove. Of all his movies, only Spartacus rewarded a cast member with an acting award, Peter Ustinov for Best Supporting Actor.

This list includes a list of awards for which Kubrick himself was personally nominated or won in the area of Oscars, Golden Globes, BAFTA, and the notorious Raspberry.

| Year | Title | Awards (limited to Oscars, Golden Globes, BAFTAs and Razzies) |

|---|---|---|

| 1953 | Fear and Desire | |

| 1955 | Killer's Kiss | |

| 1956 | The Killing | Nominated for BAFTA Award: Best Film from Any Source |

| 1957 | Paths of Glory | Nominated for BAFTA Award: Best Film from Any Source |

| 1960 | Spartacus | Won Golden Globe: Best Drama Picture, Nominated Golden Globe: Best Picture Nominated for BAFTA Award: Best Film from Any Source |

| 1962 | Lolita | Nominated for Oscar: Best Adapted Screenplay (Kubrick's extensive work on this was uncredited- the nominee was Vladimir Nabokov) Nominated for Golden Globes: Best Director |

| 1964 | Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb | Nominated for Oscars: Best Director, Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay Won BAFTA Awards: Best British Film, Best Film from any Source, Nominated BAFTA: Best British Screenplay (nomination shared with Peter George and Terry Southern) |

| 1968 | 2001: A Space Odyssey | Won Oscar : Best Special Effects Nominated for Oscars: Best Director, Best Original Screenplay (nomination shared with Arthur C. Clarke) Nominated for BAFTA: Best Film |

| 1971 | A Clockwork Orange | Nominated for Oscars: Best Director, Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay Nominated for Golden Globes: Best Director, Best Drama Picture Nominated for BAFTA Awards: Best Direction, Best Film, Best Screenplay Won 2 recognitions by The New York Film Critics: Best Director, Best Picture |

| 1975 | Barry Lyndon | Nominated for Oscars : Best Director, Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay Nominated for 2 Golden Globes: Best Director, Best Drama Picture Won BAFTA Award: Best Direction Nominated: Best Film |

| 1980 | The Shining | Nominated - Razzie Award for Worst Director |

| 1987 | Full Metal Jacket | Nominated for Oscar: Best Adapted Screenplay (nomination shared with Michael Herr, Gustav Hasford) |

| 1999 | Eyes Wide Shut |

For many individual films Kubrick was nominated for and won awards from various societies of film critics, film festivals, and both the Writers Guild of America and the Directors Guild of America.

Kubrick's lifetime achievement awards were the D.W. Griffith award from the Directors Guild of America, and another from the Director's Guild of Great Britain, and the Career Golden Lion from the Venice Film Festival. Posthumously, the Sitges - Catalonian International Film Festival awarded him the "Honorary Grand Prize" in 2008.

In the science fiction world, Kubrick has thrice won the especially coveted Hugo Award, a prize mainly for print writing and only secondarily for drama production. He also received four nominations (with one win) of the science-fiction-film-oriented Saturn awards from the Academy of Science Fiction for The Shining, an award that did not exist when Kubrick won his three Hugos.

Kubrick received two awards from major film festivals: "Best Director" from the Locarno International Film Festival in 1959 for Killer's Kiss and "Filmcritica Bastone Bianco Award" at the Venice Film Festival in 1999 for "Eyes Wide Shut". He also was nominated for the "Golden Lion" of the Venice Film Festival in 1962 for Lolita. The Venice Film Festival awarded him the "Career Golden Lion" in 1997 and the Sitges - Catalonian International Film Festival awarded him the "Honorary Grand Prize" in 2008.

In 1997, three of Kubrick's films were selected by the American Film Institute for their list of the 100 Greatest Movies in America: 2001: A Space Odyssey at #22, Dr. Strangelove at #26 and A Clockwork Orange at #46. In 2007, the AFI updated their list with 2001 ranked at #15, Dr. Strangelove ranked at #39 and Clockwork Orange ranked at #70; Spartacus was one of the new selections, ranking at #81.

In 2000, BAFTA renamed their Britannia award to the Stanley Kubrick Britannia Award. Kubrick is among filmmakers such as D.W. Griffith, Cecil B. DeMille, Irving Thalberg, and Laurence Olivier, all of whom have had annual awards named after them. Kubrick won this award in 1999, one year prior to its being renamed in his honor.

Reviews from critics

Many of Kubrick's films initially received lukewarm reviews, only to be hailed as major and seminal classics decades later. Film critic Andrew Sarris was consistently highly dismissive of Kubrick, often considering him as impersonal and misanthropic. In his 1968 book, The American Cinema, Sarris said Kubrick had "a naive faith in the power of images to transcend fuzzy feelings and vague ideas". Pauline Kael was more positive towards Kubrick's earlier work (giving one of the most glowing reviews of anyone of Lolita), but shared Sarris' view of his latter films. She derided A Clockwork Orange as being exploitative and as inverting Burgess' meaning",[127] and criticized The Shining for being a cheat with "static dialogues" lacking the " scary fun or mysterious beauty" of other horror films, but instead being obsessed with metaphysical issues that she felt bogged the film down.[128] Long after she retired she publicly denounced Kubrick's final film Eyes Wide Shut as utterly ludicrous,[129] although in the same interview she defended Kubrick's Lolita as far better than the 1998 remake.

Dublin-based film critic Paul Lynch both commends the arresting power of Kubrick's images while concerned that Kubrick has an unfeeling ivory-tower approach to life. In the same essay, he wrote both