History of Arkansas: Difference between revisions

m Reverted 1 edit by 216.134.238.10 (talk) identified as vandalism to last revision by Brandonrush. (TW) |

Brandonrush (talk | contribs) add more history up to New Madrid earthquake |

||

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

{{Lead too short|date=August 2009}} |

{{Lead too short|date=August 2009}} |

||

'''Arkansas''' was the 25th state admitted to the United States. |

'''Arkansas''' was the 25th state admitted to the United States. |

||

Early French explorers of the territory gave it its name, a corruption of Akansea, which is a phonetic spelling of the [[Illinois language|Illinois]] word for the [[Quapaw people|People of the South Wind]], now called the Quapaw, who were descendents of the Illinois people who had migrated down the [[Mississippi River]].<ref>{{ cite web |last=Key |first= Joseph |title= Quapaw |url= http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?search=1&entryID=550 |publisher= The Butler Center |work= Encyclopedia of Arkansas |date= December 16, 2011 |accessdate= April 5, 2012 }}</ref> |

|||

==Early Arkansas== |

==Early Arkansas== |

||

| Line 31: | Line 33: | ||

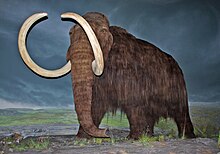

[[File:Woolly Mammoth-RBC.jpg|right|thumb|Woolly Mammoths were the primary source of food for early inhabitants of Arkansas.]] |

[[File:Woolly Mammoth-RBC.jpg|right|thumb|Woolly Mammoths were the primary source of food for early inhabitants of Arkansas.]] |

||

{{Main|Archaic period in the Americas|Paleo-Indians}} |

{{Main|Archaic period in the Americas|Paleo-Indians}} |

||

Beginning around 11700 [[Common era|B.C.E.]], the first indigenous peoples inhabited the area now known as [[Arkansas]] after crossing today's [[Bering Strait]], formerly [[Beringia]].<ref>{{ cite web |title= Origins: Ice Age Migrations 28,000 – 11,500 B.C. |url= http://arkarcheology.uark.edu/indiansofarkansas/index.html?pageName=Ice%20Age%20Migrations |last=Sabo III |first= George |date= December 18, 2008 |work= Indians of Arkansas |accessdate= January 20, 2012 }}</ref> The first people in modern-day Arkansas likely hunted [[woolly mammoth]]s by running them off cliffs or using [[clovis point]]s, and began to fish as major rivers began to thaw towards the end of [[Late Glacial Maximum|the last great ice age]].<ref> |

Beginning around 11700 [[Common era|B.C.E.]], the first indigenous peoples inhabited the area now known as [[Arkansas]] after crossing today's [[Bering Strait]], formerly [[Beringia]].<ref>{{ cite web |title= Origins: Ice Age Migrations 28,000 – 11,500 B.C. |url= http://arkarcheology.uark.edu/indiansofarkansas/index.html?pageName=Ice%20Age%20Migrations |last=Sabo III |first= George |date= December 18, 2008 |work= Indians of Arkansas |accessdate= January 20, 2012 }}</ref> The first people in modern-day Arkansas likely hunted [[woolly mammoth]]s by running them off cliffs or using [[clovis point]]s, and began to fish as major rivers began to thaw towards the end of [[Late Glacial Maximum|the last great ice age]].<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 5.</ref> Forests also began to grow around 9500 BCE, allowing for more gathering by native peoples. Crude containers became a necessity for storing gathered items. Since mammoths had became extinct, hunting [[bison]] and [[deer]] became more common. These early peoples of Arkansas likely lived in base camps and departed on hunting trips for months at a time.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 7.</ref> |

||

===Woodland and Mississippi periods=== |

===Woodland and Mississippi periods=== |

||

[[File:Chromesun |

[[File:Chromesun toltec mounds photo01.jpg|thumb|left|[[Tumulus|Burial mounds]], such as this one at [[Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park]] in northeast Arkansas, became more common during the [[Woodland Period]].]] |

||

{{Main|Woodland period|Mississippian culture}} |

{{Main|Woodland period|Mississippian culture}} |

||

Further warming led to the beginnings of agriculture in Arkansas around 650 BCE. Fields consisted of clearings, and [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native Americans]] would begin to form villages around the plot of trees they had cleared. Shelters became more permanent and [[Ceramics of indigenous peoples of the Americas|pottery became more complex]]. [[Tumulus|Burial mounds]], surviving today in places such as [[Parkin Archeological State Park]] and [[Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park]], became common in northeast Arkansas. This reliance on agriculture marks an entrance into [[Mississippian culture]] around 950 CE. Wars began occurring between [[Tribal chief|chieftains]] over land disputes. [[Platform mound]]s gain popularity in some cultures. |

Further warming led to the beginnings of agriculture in Arkansas around 650 BCE. Fields consisted of clearings, and [[Indigenous peoples of the Americas|Native Americans]] would begin to form villages around the plot of trees they had cleared. Shelters became more permanent and [[Ceramics of indigenous peoples of the Americas|pottery became more complex]].<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 9.</ref> [[Tumulus|Burial mounds]], surviving today in places such as [[Parkin Archeological State Park]] and [[Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park]], became common in northeast Arkansas.<ref>{{ cite web |last= Early |first= Ann M. |title= Indian Mounds |url= http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?entryID=573 |date= November 5, 2011 |publisher= The Butler Center |work= Encyclopedia of Arkansas |accessdate= April 5, 2012 }}</ref> This reliance on agriculture marks an entrance into [[Mississippian culture]] around 950 CE. Wars began occurring between [[Tribal chief|chieftains]] over land disputes. [[Platform mound]]s gain popularity in some cultures.<ref>{{ cite web |title= Toltec Mounds State Park |url= http://www.arkansasstateparks.com/images/pdfs/TOLTEC-06.pdf |format= PDF |year= 2006 |publisher= [[Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism]] |accessdate= April 5, 2012 }}</ref> |

||

The [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] nations that lived in Arkansas prior to the westward movement of peoples from the East were the [[Quapaw]], [[Caddo]], and [[Osage Nation]]s. While moving westward, the [[Five Civilized Tribes]] inhabited Arkansas during its territorial period. |

The [[Native Americans in the United States|Native American]] nations that lived in Arkansas prior to the westward movement of peoples from the East were the [[Quapaw]], [[Caddo]], and [[Osage Nation]]s. While moving westward, the [[Five Civilized Tribes]] inhabited Arkansas during its territorial period. |

||

| Line 48: | Line 50: | ||

===Robert La Salle and Henri De Tonti=== |

===Robert La Salle and Henri De Tonti=== |

||

[[File:Arkansas1759.png|left|thumb|Map of Arkansas that includes de Soto route, 1795]] |

[[File:Arkansas1759.png|left|thumb|Map of Arkansas that includes de Soto route, 1795]] |

||

[[René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle|Robert La Salle]] entered Arkansas in 1681 as part of his quest to find the mouth of the Mississippi River, and thus claim the entire river for [[New France]]. La Salle and his partner, [[Henri de Tonti]], succeeded in this venture, claiming the river in April 1682. La Salle would return to [[France]] while dispatching de Tonti to wait for him and hold [[Starved Rock State Park|Fort St. Louis]]. On the king's orders, La Salle returned to colonize the [[Gulf of Mexico]] for the French, but ran aground in [[Matagorda Bay]]. La Salle led three expeditions on foot searching for the Mississippi River, but his third party mutinied near [[Navasota, Texas]] in 1687. de Tonti learned of La Salle's Texas expeditions and traveled south in an effort to locate him along the Mississippi River. Along this journey south, de Tonti founded [[Arkansas Post]] as a waypoint for his searches. La Salle's party, now led by his brother, stumbled upon the Post and were greeted kindly by Quapaw with fond memories of La Salle. The troupe thought it best to lie and say La Salle remained at his new coastal colony.<ref> |

[[René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle|Robert La Salle]] entered Arkansas in 1681 as part of his quest to find the mouth of the Mississippi River, and thus claim the entire river for [[New France]]. La Salle and his partner, [[Henri de Tonti]], succeeded in this venture, claiming the river in April 1682. La Salle would return to [[France]] while dispatching de Tonti to wait for him and hold [[Starved Rock State Park|Fort St. Louis]]. On the king's orders, La Salle returned to colonize the [[Gulf of Mexico]] for the French, but ran aground in [[Matagorda Bay]]. La Salle led three expeditions on foot searching for the Mississippi River, but his third party mutinied near [[Navasota, Texas]] in 1687. de Tonti learned of La Salle's Texas expeditions and traveled south in an effort to locate him along the Mississippi River. Along this journey south, de Tonti founded [[Arkansas Post]] as a waypoint for his searches. La Salle's party, now led by his brother, stumbled upon the Post and were greeted kindly by Quapaw with fond memories of La Salle. The troupe thought it best to lie and say La Salle remained at his new coastal colony.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 31.</ref> |

||

The French colonization of the Mississippi Valley would end with the later destruction of [[Fort St. Louis]] without de Tonti establishing the small trading stop, Arkansas Post. The party originally lead by La Salle would depart the Post and continue north to [[Montreal]], where interest was spurred in explorers who had the knowledge that the French had a holding in the region.<ref> |

The French colonization of the Mississippi Valley would end with the later destruction of [[Fort St. Louis]] without de Tonti establishing the small trading stop, Arkansas Post. The party originally lead by La Salle would depart the Post and continue north to [[Montreal]], where interest was spurred in explorers who had the knowledge that the French had a holding in the region.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 32</ref> |

||

===Arkansas Post=== |

===Arkansas Post=== |

||

| Line 56: | Line 58: | ||

The first settlement in Arkansas was Arkansas Post, established in 1686 by Henri de Tonti. The post disbanded for unknown reasons in 1699 but was reestablished in 1721 in the same location. Located slightly upriver from the confluence of the [[Arkansas River]] and [[Mississippi River]], the remote post was a center of trade and home base for [[trapping|fur trappers]] in the region to trade their wares. The French settlers mingled and in some cases even intermarried with Quapaw natives, sharing a dislike of English and [[Chickasaw]] who were allies at the time. A [[moratorium]] on furs imposed by [[Canada]] severely affected the post's economy, and many settlers began to move out of the [[Mississippi River Valley]]. Scottish banker [[John Law (economist)|John Law]] saw the struggling post and attempted to entice settlers to emigrate from Germany to start an agriculture settlement at Arkansas Post, but his efforts failed when Law-created [[Mississippi Company#The Mississippi Bubble|Mississippi Bubble]] burst in 1720. The French maintained the post throughout this time mostly due to its strategic significance along the Mississippi River. The post was moved back further from the Mississippi River in 1749 after the English with their Chickasaw allies attacked, it was moved downriver in 1756 to be closer to a Quapaw defensive line that had been established and to serve as an [[entrepôt]] during the [[Seven Years' War]] and prevent attacks from the Spanish along the Mississippi. After the war ended, the post was again moved upriver out of the floodplain in 1779. |

The first settlement in Arkansas was Arkansas Post, established in 1686 by Henri de Tonti. The post disbanded for unknown reasons in 1699 but was reestablished in 1721 in the same location. Located slightly upriver from the confluence of the [[Arkansas River]] and [[Mississippi River]], the remote post was a center of trade and home base for [[trapping|fur trappers]] in the region to trade their wares. The French settlers mingled and in some cases even intermarried with Quapaw natives, sharing a dislike of English and [[Chickasaw]] who were allies at the time. A [[moratorium]] on furs imposed by [[Canada]] severely affected the post's economy, and many settlers began to move out of the [[Mississippi River Valley]]. Scottish banker [[John Law (economist)|John Law]] saw the struggling post and attempted to entice settlers to emigrate from Germany to start an agriculture settlement at Arkansas Post, but his efforts failed when Law-created [[Mississippi Company#The Mississippi Bubble|Mississippi Bubble]] burst in 1720. The French maintained the post throughout this time mostly due to its strategic significance along the Mississippi River. The post was moved back further from the Mississippi River in 1749 after the English with their Chickasaw allies attacked, it was moved downriver in 1756 to be closer to a Quapaw defensive line that had been established and to serve as an [[entrepôt]] during the [[Seven Years' War]] and prevent attacks from the Spanish along the Mississippi. After the war ended, the post was again moved upriver out of the floodplain in 1779. |

||

The secret [[Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762)|Treaty of Fontainebleau]] gave Spain the [[Louisiana Territory]] in exchange for [[Florida]] (although credit is often given to the public [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|Treaty of Paris]]), including present-day Arkansas. The Spanish show little interest in Arkansas Post except for the land grants meant to inspire settlement around the post which would later cause problems with land titles given by the American government. |

The secret [[Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762)|Treaty of Fontainebleau]] gave Spain the [[Louisiana Territory]] in exchange for [[Florida]] (although credit is often given to the public [[Treaty of Paris (1763)|Treaty of Paris]]), including present-day Arkansas. The Spanish show little interest in Arkansas Post except for the land grants meant to inspire settlement around the post which would later cause problems with land titles given by the American government. The post's position {{convert|4|mi|km}} up the Arkansas River made it a hub for trappers to start their journeys, although it also served as a diplomatic center for relations between the Spanish and Quapaw. Many who stopped at Arkansas Post were simply passing through on their way up or down river and needed supplies or rest. Inhabitants of the post included approximately 10 elite merchants, some domestic slaves, and the wives and children of trappers who were out in the wilderness. Only the elites actually lived inside the defensive walls of the post, with the remaining people surrounding the fortification. In April 1783, Arkansas saw it's only battle of the [[American Revolutionary War]], a brief siege of the post by British Captain [[James Colbert]], with the assistance of Choctaw and Chicksaw Indians. |

||

==Louisiana Purchase and territorial status== |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:LouisianaPurchase.png|right|thumb|The modern United States, with Louisiana Purchase overlay (in green).]] |

|||

Arkansas is one of several [[U.S. state]]s formed from the territory purchased from [[Napoleon Bonaparte]] in the [[Louisiana Purchase]]. The early Spanish or French explorers of the territory gave it its name, probably a phonetic spelling of the [[Illinois language|Illinois]] word for the Quapaw people, who lived downriver from them. |

|||

Although the [[United States of America]] had gained separation from the British as a result of the Revolutionary War, Arkansas remained in Spanish hands after the conflict. Americans began moving west to [[Kentucky]] and [[Tennessee]], and the United States wanted to guarantee these people that the Spanish possession of the Mississippi River would not disrupt commerce. [[Napoleon Bonaparte]]'s conquest of Spain shortly after the American Revolution forced the Spanish to cede [[Louisiana (New France)|Louisiana]], including Arkansas, to the French via the [[Third Treaty of San Ildefonso]] in 1800. England declared war on France in 1803, and Napoleon sold his land in the new world to the United States, today known as the [[Louisiana Purchase]]. The size of the country doubled with the purchase, and an influx of new White settlers led to a changed dynamic between Native Americans and Arkansans.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 78.</ref> Prior to the Louisiana Purchase, the relationship between the two groups was a "middle ground" of give and take. These relationships would deteriorate all across the frontier, including in Arkansas.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 79.</ref> |

|||

[[Thomas Jefferson]] initiated the [[Lewis and Clark Expedition]] to find the nation's new northern boundary, and the [[Dunbar Hunter Expedition]], led by [[William Dunbar (explorer)|William Dunbar]], was sent to establish the new southern boundary. The group was intended to explore the [[Red River]], but due to Spanish hostility settled on a tour up the [[Ouachita River]] to explore the [[Hot Springs National Park|hot springs]] in central Arkansas. Leaving in October 1804 and parting company at [[Monroe, Louisiana|Fort Miro]] on January 16, 1805,<ref>{{ cite web |last= Berry |first= Terry |title= Hunter-Dunbar Expedition |publisher= The Butler Center |work= Encyclopedia of Arkansas |url= http://www.encyclopediaofarkansas.net/encyclopedia/entry-detail.aspx?search=1&entryID=2205 |date= May 2, 2011 |accessdate= April 5, 2012 }}</ref> their reports included detailed accounts of give and take between Native Americans and trappers, detailed flora and fauna descriptions, and a chemical analysis of the "healing waters" of the hot springs.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 85.</ref> Also included was useful information for settlers to navigate the area and descriptions of the people inhabiting south Arkansas. The settler-Native American relationship deteriorated further following the [[1812 New Madrid earthquake]], viewed by some as punishment for accepting and assimilating into White culture. Many [[Cherokee]] left their farms and moved shortly after a speech admonishing the tribe for departing from tradition following a speech in June 1812 by a tribal chief.<ref>Arnold 2002, p. 89.</ref> |

|||

==Early 19th century territory and statehood== |

|||

{{See also|Arkansas Territorial Militia}} |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

The region is organized as the [[Territory of Arkansas]] on July 4, 1819, but the territory was admitted to the Union as the [[state of Arkansas]] on June 15, 1836, as the 25th state and the 13th [[slave state]]. |

The region is organized as the [[Territory of Arkansas]] on July 4, 1819, but the territory was admitted to the Union as the [[state of Arkansas]] on June 15, 1836, as the 25th state and the 13th [[slave state]]. |

||

| Line 110: | Line 113: | ||

* [[History of the Southern United States]] |

* [[History of the Southern United States]] |

||

== |

==Notes== |

||

{{reflist}} |

{{reflist}} |

||

==References== |

|||

* {{cite book |last4= Whayne |first4= Jeannie M. |last2= DeBlack |first2= Thomas A. |last3= Sabo III |first3= George |last1= Arnold |first1= Morris S. |title= Arkansas: A narrative history |edition= 1st |year= 2002 |publisher= The University of Arkansas Press |location= Fayetteville, Arkansas |isbn= 1-55728-724-4 |oclc= 49029558 }} |

|||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

| Line 117: | Line 123: | ||

==External links== |

==External links== |

||

{{Commonscat}} |

|||

* [http://www.ark-ives.com/ Arkansas History Commission and State Archives] |

* [http://www.ark-ives.com/ Arkansas History Commission and State Archives] |

||

* [http://www.arkansas.com/things-to-do/history-heritage/ Arkansas history and heritage] |

* [http://www.arkansas.com/things-to-do/history-heritage/ Arkansas history and heritage] |

||

Revision as of 18:11, 5 April 2012

Important dates in Arkansas's history |

|---|

|

Template:Topical guide (historical)

Arkansas was the 25th state admitted to the United States.

Early French explorers of the territory gave it its name, a corruption of Akansea, which is a phonetic spelling of the Illinois word for the People of the South Wind, now called the Quapaw, who were descendents of the Illinois people who had migrated down the Mississippi River.[1]

Early Arkansas

Archaic and Paleo periods

Beginning around 11700 B.C.E., the first indigenous peoples inhabited the area now known as Arkansas after crossing today's Bering Strait, formerly Beringia.[2] The first people in modern-day Arkansas likely hunted woolly mammoths by running them off cliffs or using clovis points, and began to fish as major rivers began to thaw towards the end of the last great ice age.[3] Forests also began to grow around 9500 BCE, allowing for more gathering by native peoples. Crude containers became a necessity for storing gathered items. Since mammoths had became extinct, hunting bison and deer became more common. These early peoples of Arkansas likely lived in base camps and departed on hunting trips for months at a time.[4]

Woodland and Mississippi periods

Further warming led to the beginnings of agriculture in Arkansas around 650 BCE. Fields consisted of clearings, and Native Americans would begin to form villages around the plot of trees they had cleared. Shelters became more permanent and pottery became more complex.[5] Burial mounds, surviving today in places such as Parkin Archeological State Park and Toltec Mounds Archeological State Park, became common in northeast Arkansas.[6] This reliance on agriculture marks an entrance into Mississippian culture around 950 CE. Wars began occurring between chieftains over land disputes. Platform mounds gain popularity in some cultures.[7]

The Native American nations that lived in Arkansas prior to the westward movement of peoples from the East were the Quapaw, Caddo, and Osage Nations. While moving westward, the Five Civilized Tribes inhabited Arkansas during its territorial period.

Colonial Arkansas

The expeditions of Hernando de Soto, Marquette and Joliet

The first European to reach Arkansas was the Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto in 1541. de Soto wandered among settlements, inquiring about gold and other valuable natural resources. He encountered the Casqui in northeast Arkansas, who sent him north around Devil's Elbow to the Pacaha, the enemy of the Casqui. Upon arrival in the Pacaha village, the Casqui who had followed behind de Soto attacked and raided the village. De Soto ultimately engaged the two tribe's chiefs in a peace treaty before continuing on to travel much of Arkansas. The explorer died in May 1542 and was thrown into the Mississippi River near McArthur, Arkansas to prevent local tribes from knowing he was mortal. In 1673, French explorers Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet reached the Arkansas River as part of an expedition to find the mouth of the Mississippi River. After a calumet with friendly Quapaw, the group suspected the Spanish to be nearby and returned north.

Robert La Salle and Henri De Tonti

Robert La Salle entered Arkansas in 1681 as part of his quest to find the mouth of the Mississippi River, and thus claim the entire river for New France. La Salle and his partner, Henri de Tonti, succeeded in this venture, claiming the river in April 1682. La Salle would return to France while dispatching de Tonti to wait for him and hold Fort St. Louis. On the king's orders, La Salle returned to colonize the Gulf of Mexico for the French, but ran aground in Matagorda Bay. La Salle led three expeditions on foot searching for the Mississippi River, but his third party mutinied near Navasota, Texas in 1687. de Tonti learned of La Salle's Texas expeditions and traveled south in an effort to locate him along the Mississippi River. Along this journey south, de Tonti founded Arkansas Post as a waypoint for his searches. La Salle's party, now led by his brother, stumbled upon the Post and were greeted kindly by Quapaw with fond memories of La Salle. The troupe thought it best to lie and say La Salle remained at his new coastal colony.[8]

The French colonization of the Mississippi Valley would end with the later destruction of Fort St. Louis without de Tonti establishing the small trading stop, Arkansas Post. The party originally lead by La Salle would depart the Post and continue north to Montreal, where interest was spurred in explorers who had the knowledge that the French had a holding in the region.[9]

Arkansas Post

The first settlement in Arkansas was Arkansas Post, established in 1686 by Henri de Tonti. The post disbanded for unknown reasons in 1699 but was reestablished in 1721 in the same location. Located slightly upriver from the confluence of the Arkansas River and Mississippi River, the remote post was a center of trade and home base for fur trappers in the region to trade their wares. The French settlers mingled and in some cases even intermarried with Quapaw natives, sharing a dislike of English and Chickasaw who were allies at the time. A moratorium on furs imposed by Canada severely affected the post's economy, and many settlers began to move out of the Mississippi River Valley. Scottish banker John Law saw the struggling post and attempted to entice settlers to emigrate from Germany to start an agriculture settlement at Arkansas Post, but his efforts failed when Law-created Mississippi Bubble burst in 1720. The French maintained the post throughout this time mostly due to its strategic significance along the Mississippi River. The post was moved back further from the Mississippi River in 1749 after the English with their Chickasaw allies attacked, it was moved downriver in 1756 to be closer to a Quapaw defensive line that had been established and to serve as an entrepôt during the Seven Years' War and prevent attacks from the Spanish along the Mississippi. After the war ended, the post was again moved upriver out of the floodplain in 1779.

The secret Treaty of Fontainebleau gave Spain the Louisiana Territory in exchange for Florida (although credit is often given to the public Treaty of Paris), including present-day Arkansas. The Spanish show little interest in Arkansas Post except for the land grants meant to inspire settlement around the post which would later cause problems with land titles given by the American government. The post's position 4 miles (6.4 km) up the Arkansas River made it a hub for trappers to start their journeys, although it also served as a diplomatic center for relations between the Spanish and Quapaw. Many who stopped at Arkansas Post were simply passing through on their way up or down river and needed supplies or rest. Inhabitants of the post included approximately 10 elite merchants, some domestic slaves, and the wives and children of trappers who were out in the wilderness. Only the elites actually lived inside the defensive walls of the post, with the remaining people surrounding the fortification. In April 1783, Arkansas saw it's only battle of the American Revolutionary War, a brief siege of the post by British Captain James Colbert, with the assistance of Choctaw and Chicksaw Indians.

Louisiana Purchase and territorial status

Although the United States of America had gained separation from the British as a result of the Revolutionary War, Arkansas remained in Spanish hands after the conflict. Americans began moving west to Kentucky and Tennessee, and the United States wanted to guarantee these people that the Spanish possession of the Mississippi River would not disrupt commerce. Napoleon Bonaparte's conquest of Spain shortly after the American Revolution forced the Spanish to cede Louisiana, including Arkansas, to the French via the Third Treaty of San Ildefonso in 1800. England declared war on France in 1803, and Napoleon sold his land in the new world to the United States, today known as the Louisiana Purchase. The size of the country doubled with the purchase, and an influx of new White settlers led to a changed dynamic between Native Americans and Arkansans.[10] Prior to the Louisiana Purchase, the relationship between the two groups was a "middle ground" of give and take. These relationships would deteriorate all across the frontier, including in Arkansas.[11]

Thomas Jefferson initiated the Lewis and Clark Expedition to find the nation's new northern boundary, and the Dunbar Hunter Expedition, led by William Dunbar, was sent to establish the new southern boundary. The group was intended to explore the Red River, but due to Spanish hostility settled on a tour up the Ouachita River to explore the hot springs in central Arkansas. Leaving in October 1804 and parting company at Fort Miro on January 16, 1805,[12] their reports included detailed accounts of give and take between Native Americans and trappers, detailed flora and fauna descriptions, and a chemical analysis of the "healing waters" of the hot springs.[13] Also included was useful information for settlers to navigate the area and descriptions of the people inhabiting south Arkansas. The settler-Native American relationship deteriorated further following the 1812 New Madrid earthquake, viewed by some as punishment for accepting and assimilating into White culture. Many Cherokee left their farms and moved shortly after a speech admonishing the tribe for departing from tradition following a speech in June 1812 by a tribal chief.[14]

The region is organized as the Territory of Arkansas on July 4, 1819, but the territory was admitted to the Union as the state of Arkansas on June 15, 1836, as the 25th state and the 13th slave state.

Arkansas chartered two banks during its first legislative session, a State Bank and a Real Estate Bank. Both would fail within a decade and the bonds they had issued became entangled in legally questionable deals. They would come to be known as the "Holford Bonds" because they eventually fell into the hands of a London Banker named James Holford. The issue of whether or not the bonds were a legitimate state debt and whether or not they would be repaid would be a political issue in the state throughout the 1800s.

Arkansas played a key role in aiding Texas in its war for independence with Mexico, sending troops and materials to Texas to help fight the war. The proximity of the city of Washington to the Texas border involved the town in the Texas Revolution of 1835-36. Some evidence suggests Sam Houston and his compatriots planned the revolt in a tavern at Washington in 1834.[15] When the fighting began a stream of volunteers from Arkansas and the eastern states flowed through the town toward the Texas battle fields.

When the Mexican-American War began in 1846, Washington became a rendezvous for volunteer troops. Governor Thomas S. Drew issued a proclamation calling on the state to furnish one regiment of cavalry and one battalion of infantry to join the United States Army. Ten companies of men assembled here where they were formed into the first Regiment of Arkansas Cavalry.

Civil War

Arkansas refused to join the Confederate States of America until after United States President Abraham Lincoln called for troops to respond to the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter, South Carolina. The state was unwilling to fight against its neighbors and seceded from the Union on May 6, 1861. While the state was not a chief battleground, it was the site of numerous small-scale battles during the American Civil War. When Union forces captured Little Rock in 1863, the Confederate government relocated the state capital to the town of Washington in the southwest part of the state.

Natives of during the Civil War included Confederate Major General Patrick Cleburne. Considered by many to be one of the most brilliant Confederate division commanders of the war, Cleburne was often referred to as "The Stonewall of the West." Also of note was Major General Thomas C. Hindman. A former United States Representative, Hindman commanded Confederate forces at the battles of Cane Hill and Prairie Grove.

Late 19th century and disfranchisement

Under the Military Reconstruction Act, Congress readmitted Arkansas in June 1868. With the right to suffrage, freedmen began to participate vigorously in the political life of the state. From 1869 to 1893, more than 45 African American men were elected to seats in the state legislature. As in other states, they were already leaders in their communities: often ministers or teachers, or literate men who had returned from the North. Some had both white and African-American ancestors.

In 1874, the Brooks-Baxter War shook Little Rock. The dispute about the legal governor of the state was settled when President Ulysses S. Grant ordered that Joseph Brooks to disperse his militant supporters.

In 1881, the Arkansas state legislature enacted a bill that adopted an official pronunciation for the state, to combat a controversy then raging.

During the late 1880s and 1890s, the Democrats worked to consolidate their power and prevent alliances among African Americans and poor whites in the years of agricultural depression. They were facing competition from the Populist and other third parties. In 1891, state legislators passed a statute requiring a literacy test for voter registration, when more than 25% of the population could not read or write. In 1892 the state passed a constitutional amendment that imposed a poll tax and associated residency requirements for voting, which combined barriers sharply reduced the numbers of blacks and poor whites on the voter rolls, and voter participation dropped sharply.[16]

Having consolidated power among its supporters, by 1900 the state Democratic Party began relying on all-white primaries at the county and state level. This was one more door closed against blacks, as the primaries had become the only competitive political contests; the Democratic Party primary winner was always elected.[16] In 1900 African Americans numbered 366,984 in the state and made up 28% of the population - together with poor whites, more than one-third of the citizens were disfranchised.[17] Since they could not vote, they could not serve on juries, which were limited to voters. They were shut out of the political process.

20th century

Great Migration

The growth in industrial jobs in the North and Midwest attracted many blacks from the South in the first half of the 20th century. Their migration out of the South was a reach toward a better quality of life where they could vote and live more fully as citizens. Agricultural changes also meant that farm workers were not needed in as great number. Thousands left Arkansas. During the years of World War II, blacks also migrated to California, where good jobs were expanding in defense industries

Civil rights movement

In one of the first major cases of the African-American civil rights era, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Topeka Board of Education (1954) that segregated schools were unconstitutional. Both of Arkansas' U.S. Senators (J. William Fulbright and John L. McClellan) and all six of its U.S. Representatives were among those who signed the Southern Manifesto in response.

The Little Rock Nine incident of 1957 centered around Little Rock Central High School brought Arkansas to national attention. After the Little Rock School Board had voted to begin carrying out desegregation in compliance with the law, segregationist protesters physically blocked nine black students recruited by the NAACP from entering the school. Governor Orval Faubus deployed the Arkansas National Guard to support the segregationists, and only backed down after Judge Ronald Davies of U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Arkansas granted an injunction from the U.S. Department of Justice compelling him to withdraw the Guard.

White mobs began to riot when the nine black students began attending school. President Dwight D. Eisenhower, on the request of Little Rock Mayor, deployed the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock and federalized the Arkansas National Guard to protect the students and ensure their safe passed to school. Little Rock's four public high schools were closed in September 1958, only reopening a year later. Integration across all grades was finally achieved in fall 1972.

Bill Clinton

Bill Clinton, born in Hope, Arkansas, served nearly twelve years as the 40th and 42nd Arkansas governor before being elected 42nd president in the 1992 election.

Changing racial attitudes and growth in jobs have created a New Great Migration of African Americans back to metropolitan areas in the developing South, especially to such states as Georgia, North Carolina and Texas. These have developed many knowledge industry jobs.

See also

{{{inline}}}

Notes

- ^ Key, Joseph (December 16, 2011). "Quapaw". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. The Butler Center. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ Sabo III, George (December 18, 2008). "Origins: Ice Age Migrations 28,000 – 11,500 B.C." Indians of Arkansas. Retrieved January 20, 2012.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 5.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 7.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 9.

- ^ Early, Ann M. (November 5, 2011). "Indian Mounds". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. The Butler Center. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ "Toltec Mounds State Park" (PDF). Arkansas Department of Parks and Tourism. 2006. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 31.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 32

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 78.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 79.

- ^ Berry, Terry (May 2, 2011). "Hunter-Dunbar Expedition". Encyclopedia of Arkansas. The Butler Center. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 85.

- ^ Arnold 2002, p. 89.

- ^ Taylor, Jim. "Old Washington State Park Conserves Town's Heyday".

- ^ a b "White Primary" System Bars Blacks from Politics - 1900, The Arkansas News, Spring 1987, p.3, Old Statehouse, accessed 22 Mar 2008

- ^ Historical Census Browser, 1900 US Census, University of Virginia, accessed 15 Mar 2008

References

- Arnold, Morris S.; DeBlack, Thomas A.; Sabo III, George; Whayne, Jeannie M. (2002). Arkansas: A narrative history (1st ed.). Fayetteville, Arkansas: The University of Arkansas Press. ISBN 1-55728-724-4. OCLC 49029558.

Further reading

- Christ, Mark K. Civil War Arkansas, 1863: The Battle for a State (University of Oklahoma Press, 2010) 321 pp. isbn 978-0-8061-4087-2