History of Hungary: Difference between revisions

m →Age of elected Kings: Typo fixing and cleanup, typos fixed: so called → so-called using AWB (8414) |

|||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

The eastern part of the kingdom ([[Partium]] and [[Transylvania]]) became at first an independent principality, but gradually was brought under Turkish rule as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The remaining central area (most of present-day Hungary), including the capital of Buda, became a province of the [[Ottoman Empire]]. Much of the land was devastated by recurrent warfare. Most small Hungarian settlements disappeared. Rural people living in the now Ottoman provinces could survive only in larger settlements known as [[Khaz towns]], which were owned and protected directly by the Sultan. The Turks were indifferent to the sect of Christianity practiced by their Hungarian subjects. |

The eastern part of the kingdom ([[Partium]] and [[Transylvania]]) became at first an independent principality, but gradually was brought under Turkish rule as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The remaining central area (most of present-day Hungary), including the capital of Buda, became a province of the [[Ottoman Empire]]. Much of the land was devastated by recurrent warfare. Most small Hungarian settlements disappeared. Rural people living in the now Ottoman provinces could survive only in larger settlements known as [[Khaz towns]], which were owned and protected directly by the Sultan. The Turks were indifferent to the sect of Christianity practiced by their Hungarian subjects. |

||

For this reason, a majority of Hungarians living under Ottoman rule became Protestant (largely Calvinist), as Habsburg counter-reformation efforts could not penetrate Ottoman lands. Largely throughout this time, Pozsony (Pressburg, today: [[Bratislava]]) acted as the capital (1536–1784), coronation town (1563–1830) and seat of the Diet of Hungary (1536–1848). Nagyszombat (modern [[Trnava]]) acted in turn as the religious center, starting from 1541. |

For this reason, a majority of Hungarians living under Ottoman rule became Protestant (largely Calvinist), as Habsburg counter-reformation efforts could not penetrate Ottoman lands. Largely throughout this time, Pozsony (Pressburg, today: [[Bratislava]]) acted as the capital (1536–1784), coronation town (1563–1830) and seat of the Diet of Hungary (1536–1848). Nagyszombat (modern [[Trnava]]) acted in turn as the religious center, starting from 1541. The vast majority of the seventeen and nineteen thousands Ottoman soldiers in service in the Ottoman fortresses in the territory of Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs instead of ethnic Turkish people.<ref>Laszlo Kontler, "A History of Hungary" p. 145</ref> Southern Slavs were also acting as akinjis and other light troops intended for pillaging in the territory of present-day Hungary.<ref>Inalcik Halil: "The Ottoman Empire"</ref> |

||

In 1558 the [[Transylvania]]n [[Diet (assembly)|Diet]] of [[Turda]] declared free practice of both the [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] and [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] religions, but prohibited [[Calvinism]]. Ten years later, in 1568, the Diet extended this freedom, declaring that: "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion". Four religions were declared as accepted (''recepta'') religions, while [[Orthodox Christianity]] was "tolerated" (though the building of stone Orthodox churches was forbidden). Hungary entered the [[Thirty Years' War]], Royal (Habsburg) Hungary joined the Catholic side, until Transylvania joined the Protestant side. |

In 1558 the [[Transylvania]]n [[Diet (assembly)|Diet]] of [[Turda]] declared free practice of both the [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] and [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] religions, but prohibited [[Calvinism]]. Ten years later, in 1568, the Diet extended this freedom, declaring that: "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion". Four religions were declared as accepted (''recepta'') religions, while [[Orthodox Christianity]] was "tolerated" (though the building of stone Orthodox churches was forbidden). Hungary entered the [[Thirty Years' War]], Royal (Habsburg) Hungary joined the Catholic side, until Transylvania joined the Protestant side. |

||

Revision as of 13:48, 16 October 2012

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2009) |

| History of Hungary |

|---|

|

|

|

Hungary is a country in Central Europe. Its history under this name dates to the early Middle Ages, when Pannonian Basin was conquered by the Hungarians, a semi-nomadic people in that time. For history of the area before this period, see Pannonian basin before Hungary.

Early history

The oldest archaeological site in Hungary is Vértesszőlős where in 1965 palaeolithic Oldowan pebble tools, and an early human fossil, nicknamed "Samu", a 350,000-year-old Homo Erectus was discovered.

The Roman Empire conquered territory west of the Danube between 35 and 9 BCE From 9 BC to the end of the 4th century AD Pannonia, the western part of the basin was part of the Roman Empire. In the final stages of the expansion of the Roman empire, for a short while the Carpathian Basin fell under Mediterranean influence Greco-Roman civilization - town centers, paved roads, and written sources were all part of the advances to which the "Migration of Peoples" put an end.

After the Western Roman Empire collapsed under the stress of the migration of Germanic tribes and Carpian pressure, the Migration Period continued bringing many invaders to Europe. Among the first to arrive were the Huns, who built up a powerful empire under Attila in 435 CE. Attila the Hun was regarded in past centuries as an ancestral ruler of the Hungarians, but this is now considered to be erroneous.[1] It is believed that the origin of the name "Hungary" does not come from the Central Asian Hun nomadic invaders, but rather originated from the 7th century, when Magyar tribes were part of a Bulgar alliance called On-Ogour, which in Bulgar Turkic meant "(the) Ten Arrows".[2] After Hunnish rule faded, the Germanic Ostrogoths, Lombards then Slavs came to Pannonia, and the Gepids had a presence in the eastern part of the Carpathian Basin for about 100 years. In the 560s the Avars founded the Avar Khaganate,[3] a state which maintained supremacy in the region for more than two centuries and had the military power to launch attacks against its neighboring empires. The Avar Khaganate was weakened by constant wars and outside pressure, and the Franks under Charlemagne managed to defeat the Avars, ending their 250-year rule. In the middle of the 9th century, the Slavic Balaton Principality, also known as Lower Pannonia, was established by the Franks as a frontier march when they destroyed the Avar state in the western part of the Pannonian plain; however this vassal state was destroyed in 900 by Hungarian tribes. Much of early Hungarian history is recorded in the following Hungarian chronicles, retelling the early legends and history of the Huns, Magyars and the Kingdom of Hungary:

- Anonymi Gesta Hungarorum (Anonymous "Deeds of the Hungarians") by Magister P. (around 1200)

- Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum or Gesta Hungarorum (II) ("Deeds of the Huns and Hungarians" or just "Deeds of the Hungarians") by Simon of Kéza (late 13th century)

- Chronicon Pictum ("Illuminated Chronicle") (late 14th century)

- Chronicle of the Hungarians by Johannes de Thurocz (1480s)

Middle Ages (895–1526)

Árpád was the Magyar leader whom sources name as the single leader who unified the Magyar tribes via the Covenant of Blood (Template:Lang-hu), forging what was thereafter known as the Hungarian nation.[4] Árpád led the new nation to the Carpathian Basin in the 9th century.[4] From 895 to 902 the whole area of the Carpathian Basin was conquered by the Hungarians.[5] After that, an early Hungarian state (the Principality of Hungary, founded in 895) was formed in this territory. The military power of the nation allowed the Hungarians to conduct successful fierce campaigns and raids as far as today's Spain.[6] A later defeat at the Battle of Lechfeld in 955 signaled an end to raids on western territories (Byzantine raids continued until 970), and links between the tribes weakened. The ruling prince (fejedelem) Géza of the Árpád dynasty, who ruled only part of the united territory, the nominal overlord of all seven Magyar tribes, aimed to integrate Hungary into Christian Western Europe, rebuilding the state according to the Western political and social model.[7] He established a dynasty by naming his son Vajk (the later King Stephen I of Hungary) as his successor. This was contrary to the then-dominant tradition of the succession of the eldest surviving member of the ruling family. (See:agnatic seniority) By ancestral right prince Koppány, -as the oldest member of the dynasty- should have claimed the throne, but Géza chose his first-born son to be his successor.[8] The fight in the chief prince's family started after Géza's death, in 997. Duke Koppány took up arms, and many people in Transdanubia joined him. The rebels represented the old faith and order, ancient human rights, tribal independence and pagan belief, but Stephen won a decisive victory over his uncle Koppány, and had him executed.

The Patrimonial Kingdom

Hungary was recognized as a Catholic Apostolic Kingdom under Saint Stephen I. Stephen was the son of Géza[9] and thus a descendant of Árpád.

Stephen was crowned by the Holy Crown of Hungary in December 1000 AD in the capital, Esztergom. The Papacy confers on him the right to have the cross carried before him, with full administrative authority over bishoprics and churches. By 1006, Stephen had solidified his power, eliminating all rivals who either wanted to follow the old pagan traditions or wanted an alliance with the Eastern Christian Byzantine Empire. Then he started sweeping reforms to convert Hungary into a western feudal state, complete with forced Christianization.[10] Stephen established a network of 10 episcopal and 2 archiepiscopal sees, and ordered the buildup of monasteries churches and cathedrals. In the earliest times Hungarian language was written in a runic-like script. The country switched to the Latin alphabet under Stephen.

From 1000 to 1844, Latin was the official language of the country. He followed the Frankish administrative model: The whole of this land was divided into counties (megyék), each under a royal official called an ispán count (Template:Lang-la)—later főispán (Template:Lang-la). This official represented the king’s authority, administered its population, and collected the taxes that formed the national revenue. Each ispán maintained an armed force of freemen at his fortified headquarters (castrum or vár).

What emerged was a strong kingdom[11] that withstood attacks from German kings and Emperors, and nomadic tribes following the Hungarians from the East, integrating some of the latter into the population (along with Germans invited to Transylvania and the northern part of the kingdom, especially after the Battle of Mohi), and conquering Croatia in 1091.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18] According to an alternative history based on the document Pacta Conventa, which is most likely a forgery[19] Hungary and Croatia created a personal union. There is no undoubtedly genuine document of the personal union, and medieval sources mention the annexation into the Hungarian kingdom.

After the Great Schism (The East-West Schism /formally in 1054/, between Western Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christianity.) Hungary determined itself as the easternmost bastion of Western civilisation (This statement was affirmed later by Pope Pius II who wrote that to Emperor Friedrich III, "Hungary is the shield of Christianity and the defender of Western civilization").[citation needed]

Important members of the Árpád dynasty:

- Coloman the "Book-lover" (King: 1095–1116):

One of his most famous laws was half a millennium ahead of its time: De strigis vero quae non sunt, nulla amplius quaestio fiat (As for the matter of witches, no such things exist, therefore no further investigations or trials are to be held).

- Béla III (King: 1172–1192)

He was the most powerful and wealthiest member of the dynasty, Béla disposed of annual equivalent of 23,000 kg of pure silver. It exceeded those of the French king (estimated at some 17,000 kilograms) and was double the receipts of the English Crown.[20] He rolled back the Byzantine potency in Balkan region. In 1195, Bela III had expanded the Hungarian Kingdom southward and westward to Bosnia and Dalmatia, helping to break up the Byzantine Empire, and extending suzerainty over Serbia.[21]

- Andrew II of Hungary (King: 1205–1235)

In 1211 Andrew II of Hungary (ruled from 1205 to 1235) granted the Burzenland (in Transylvania) to the Teutonic Knights. In 1225, Andrew II expelled the Teutonic Knights from Transylvania, hence Teutonic Order had to transfer to the Baltic sea. In 1224, Andrew issued the Diploma Andreanum which unified and ensured the special privileges of the Transylvanian Saxons. It is considered the first Autonomy law in the world.[22]

He led the Fifth Crusade to the Holy Land in 1217. He set up the largest royal army in the history of Crusades (20,000 knights and 12,000 castle-garrisons). The Golden Bull of 1222 was the first constitution in Continental Europe. It limited the king's power. The Golden Bull — the Hungarian equivalent of England’s Magna Carta — to which every Hungarian king thereafter had to swear, had a twofold purpose: to reaffirm the rights of the smaller nobles of the old and new classes of royal servants (servientes regis) against both the crown and the magnates and to defend those of the whole nation against the crown by restricting the powers of the latter in certain fields and legalizing refusal to obey its unlawful/unconstitutional commands (the ius resistendi). The lesser nobles also began to present Andrew with grievances, a practice that evolved into the institution of the parliament, or Diet. Hungary became the first country where the parliament had supremacy over the kingship. The most important legal ideology was the Doctrine of the Holy Crown.

Important points of the Doctrine: The sovereignty belongs to the noble nation→(the Holy Crown). The members of the Holy Crown are the citizens of the Crown's lands. None can reach full power. The nation is sharing a portion of the political power with the ruler. Minority cannot rule over majority (against tyranny and oligarchy).

Mongol attacks

In 1241–1242, the kingdom received a major blow with the Mongol Invasion: after the defeat of the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohi,[23] Béla IV of Hungary fled, and a large part of the population died[24] in the ensuing destruction leading later to the invitation of settlers, largely from Germany. Historians estimate that up to half of Hungary's then population of 2,000,000 were victims of the Mongol invasion.[25] In the plains between 50 and 80% of the settlements were destroyed.[26] Only castles, strongly fortified cities and abbeys could withstand the assault.

During the Russian campaign, the Mongols drove some 40,000 Cumans, a nomadic tribe of pagan Kipchaks, west of the Carpathian Mountains.[27] There, the Cumans appealed to King Béla IV of Hungary for protection.[28] The Iranian Jassic people came to Hungary together with the Cumans after they were defeated by the Mongols. Cumans constituted perhaps up to 7-8% of the population of Hungary in the second half of the 13th century.[29] Over the centuries they were fully assimilated into the Hungarian population, and their language disappeared, but they preserved their identity and their regional autonomy until 1876.[30]

As a consequence, after the Mongols retreated, King Béla ordered the construction of hundreds of stone castles and fortifications, to defend against a possible second Mongol invasion. The Mongols returned to Hungary in 1286, but the new built stone-castle systems and new tactics (using a higher proportion of heavily armed knights) stopped them. The invading Mongol force was defeated near Pest by the royal army of Ladislaus IV of Hungary. As with later invasions, it was repelled handily, the Mongols losing much of their invading force.

These castles proved to be very important later in the long struggle with the Ottoman Empire. However the cost of building them indebted the Hungarian King to the major feudal landlords again, so the royal power reclaimed by Béla IV after his father Andrew II significantly weakened it was once again dispersed amongst lesser nobility. The countries of the Balkan region and the territory of Russian states fell under Ottoman/Mongolian rule very rapidly, due to the lack of the network of stone/brick castles and fortresses in these countries.

Age of elected Kings

After the destructive period of interregnum (1301–1308), the first Angevin king, Charles I of Hungary (reigned 1308–1342) - a descendant of the Árpád dynasty in the female line - successfully restored royal power, and defeated oligarch rivals, the so-called "little kings". His new fiscal, customs and monetary policies proved successful during his reign.

One of the primary sources of his power was the wealth derived from the gold mines of eastern and northern Hungary. Eventually production reached the remarkable figure of 3,000 lb. (1350 kg) of gold annually - one-third of the total production of the world as then known, and five times as much as that of any other European state.[31][32] Charles also sealed an alliance with the Polish king Casimir. After Italy, Hungary was the first European country where the renaissance appeared.[33]

The second Hungarian king in the Angevin line, Louis the Great (reigned 1342–1382) extended his rule as far as the Adriatic Sea, and occupied the Kingdom of Naples several times. In 1351, the golden bull was completed with the law of entail. Which instated that the nobles hereditary lands could not be taken away and must remain in the family. He also became king of Poland (reigned 1370–1382). During his reign lived the epic hero of Hungarian literature and warfare, the king's Champion: Nicolas Toldi. Louis had become popular in Poland because of his campaign against the Tatars and pagan Lithuanians. Two successful wars (1357–1358, 1378–1381) against Venice annexed Dalmatia and Ragusa and more territories on the Adriatic Sea. Venice also had to raise the Angevin flag in St. Mark's Square on holy days.

Some Balkan states (Vallachia, Moldova, Serbia, Bosnia) became his vassals. Louis I established a university in Pécs in 1367 (by papal accordance). The Ottoman Turks confronted the Balkan vassal states ever more often. In 1366 and 1377, Louis led successful campaigns against the Ottomans (Battle of Nicapoli in 1366). From the death of Casimir III of Poland in 1370, he was also king of Poland. He retained his strong influence in the political life of Italian Peninsula for the rest of his life.

King Louis died without a male heir, and after years of anarchy the country was stabilized only when Sigismund (reigned 1387–1437), a prince of the Luxembourg line, succeeded to the throne by marrying the daughter of Louis the Great, Queen Mary. It was not for entirely selfless reasons that one of the leagues of barons helped him to power: Sigismund had to pay for the support of the lords by transferring a sizeable part of the royal properties. For some years, the baron's council governed the country in the name of the Holy Crown; the king was imprisoned for a short time. The restoration of the authority of the central administration took decades.

In 1404 Sigismund introduced the Placetum Regnum. According to this decree, Papal bulls and messages could not be pronounced in Hungary without the consent of the king. Sigismund summoned the Council of Constance (1414–1418) to abolish the Avignon Papacy and the Papal Schism of the Catholic Church, which was resolved by the election of a new pope. In 1433 he even became Holy Roman Emperor. During his long reign the Royal castle of Buda became probably the largest Gothic palace of the late Middle Ages. After the death of Sigismund, his son in law, Albert II of Germany, was titled king of Hungary. Albert II, however, died in 1439. The first Hungarian Bible translation was completed in 1439. For a half year in 1437, there was an anti-feudal and anti-clerical peasant revolt in Transylvania which was strongly influenced by Hussite ideas. (See: Budai Nagy Antal Revolt)

From a small noble family in Transylvania, John Hunyadi grew to become one of the country's most powerful lords, thanks to his outstanding capabilities as a mercenary commander. In 1446, the parliament elected the great general John Hunyadi governor (1446–1453), then regent (1453–1456). He was a successful crusader against the Ottoman Turks, one of his greatest victories being the Siege of Belgrade in 1456. Hunyadi defended the city against the onslaught of the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II. During the siege, Pope Callixtus III ordered the bells of every European church to be rung every day at noon, as a call for believers to pray for the defenders of the city. However, in many countries (like England and Spanish kingdoms), the news of the victory arrived before the order, and the ringing of the church bells at noon was transformed into a commemoration of the victory. The Popes did not withdraw the order, and Catholic (and the older Protestant) churches still ring the noon bell in the Christian world to this day.[34]

Age of early absolutism

The last strong king was the Renaissance king Matthias Corvinus (king from 1458 to 1490). Matthias was the son of John Hunyadi. András Hess set up a printing press in Buda in 1472.

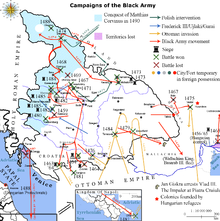

This was the first time in the medieval Hungarian kingdom that a member of the nobility, without dynastic ancestry and relationship, mounted the royal throne. A true Renaissance prince, a successful military leader and administrator, an outstanding linguist, a learned astrologer, and an enlightened patron of the arts and learning.[35] Although Matyas regularly convened the Diet and expanded the lesser nobles' powers in the counties, he exercised absolute rule over Hungary by means of huge secular bureaucracy. Matthias set out to build a great empire, expanding southward and northwest, while he also implemented internal reforms. The serfs, common people considered Matthias a just ruler because he protected them from excessive demands and other abuses by the magnates.[36] Like his father, Matthias desired to strengthen the Kingdom of Hungary to the point where it became the foremost regional power and overlord, strong enough to push back the Ottoman Empire; towards that end he deemed necessary the conquering of large parts of the Holy Roman Empire.[37] In 1479, under the leadership of general Pál Kinizsi, the Hungarian army destroyed the Ottoman and Wallachian troops at the Battle of Breadfield. Army of Hungary, almost all times destroyed the enemies when Matthias was the king. His mercenary standing army called the Black Army of Hungary (Template:Lang-hu) was an unusually big army in its age, it accomplished a series of victories in the Austrian-Hungarian War (1477-1488), capturing parts of Austria and Vienna in 1485, as well as parts of Bohemia in the Bohemian War (1468-1478). The king died without a legal successor. His library, the Bibliotheca Corviniana, was Europe's greatest collection of historical chronicles, philosophic and scientific works in the 15th century, and second only in size to the Vatican Library which mainly contained religious material. His renaissance library is a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[38]

Decline (1490–1526)

By the early 16th century, the Ottoman Empire became the second most populous state in the world, which opened the door to creation of the largest armies of the era.

The magnates, who did not want another heavy-handed king, procured the accession of Vladislaus II (King: 1490–1516), king of Bohemia (László II in Hungarian), precisely because of his notorious weakness: he was known as King Dobže, or Dobzse (meaning “Good” or, loosely, “OK”), from his habit of accepting with that word every paper laid before him.[35] Under his reign the central power began to experience severe financial difficulties, largely due to the enlargement of feudal lands at his expense. The magnates also dismantled administration and institute systems of the country. The country's defenses declined as border guards and castle garrisons went unpaid, fortresses fell into disrepair, and initiatives to increase taxes to reinforce defenses were stifled.[39] Hungary's international role was wasted, its political stability shaken, and social progress was deadlocked.

In 1514, the weakened old King Vladislaus II faced a major peasant rebellion led by György Dózsa, which was ruthlessly crushed by the nobles, led by János Szapolyai. The resulting degradation of order paved the way for Ottoman preeminence. In 1521, the strongest Hungarian fortress in the South, Nándorfehérvár (modern Belgrade) fell to the Turks, and in 1526, the Hungarian army was crushed at the Battle of Mohács. The young king Louis II, and the leader of the Hungarian army, Pál Tomori died in the battle. The early appearance of protestantism further worsened internal relations in the anarchical country.

Through the centuries Hungary kept its old "constitution", which granted special "freedoms" or rights to the nobility, the free royal towns such as Buda, Kassa (Košice), Pozsony (Bratislava), and Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca) and groups like the Jassic people or Transylvanian Saxons.

Early modern age (1526–1700)

After some 150 years of war in the south of Hungary, Ottoman forces conquered parts of the country, continuing their expansion until 1556. The Ottomans achieved their first decisive victory over the Hungarian army at the Battle of Mohács in 1526.

Subsequent decades were characterized by political chaos. A divided Hungarian nobility elected two kings simultaneously, János Szapolyai (1526–1540, of Hungarian-German origin) and the Austrian Ferdinand of Habsburg (1527–1540). Armed conflicts between the new rival monarchs further weakened the country from the internal side. With the conquest of Buda in 1541 by the Turks, Hungary was riven into three parts. The north-west (present-day Slovakia, western Transdanubia and Burgenland, western Croatia and parts of north-eastern present-day Hungary) remained under Habsburg rule; although initially independent, later it became a part of Habsburg Monarchy under the informal name Royal Hungary. The Habsburg Emperors would from then on be crowned also as Kings of Hungary. Turks were unable to conquer Northern and Western parts of Hungary.

The eastern part of the kingdom (Partium and Transylvania) became at first an independent principality, but gradually was brought under Turkish rule as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire. The remaining central area (most of present-day Hungary), including the capital of Buda, became a province of the Ottoman Empire. Much of the land was devastated by recurrent warfare. Most small Hungarian settlements disappeared. Rural people living in the now Ottoman provinces could survive only in larger settlements known as Khaz towns, which were owned and protected directly by the Sultan. The Turks were indifferent to the sect of Christianity practiced by their Hungarian subjects.

For this reason, a majority of Hungarians living under Ottoman rule became Protestant (largely Calvinist), as Habsburg counter-reformation efforts could not penetrate Ottoman lands. Largely throughout this time, Pozsony (Pressburg, today: Bratislava) acted as the capital (1536–1784), coronation town (1563–1830) and seat of the Diet of Hungary (1536–1848). Nagyszombat (modern Trnava) acted in turn as the religious center, starting from 1541. The vast majority of the seventeen and nineteen thousands Ottoman soldiers in service in the Ottoman fortresses in the territory of Hungary were Orthodox and Muslim Balkan Slavs instead of ethnic Turkish people.[40] Southern Slavs were also acting as akinjis and other light troops intended for pillaging in the territory of present-day Hungary.[41]

In 1558 the Transylvanian Diet of Turda declared free practice of both the Catholic and Lutheran religions, but prohibited Calvinism. Ten years later, in 1568, the Diet extended this freedom, declaring that: "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expelling for his religion". Four religions were declared as accepted (recepta) religions, while Orthodox Christianity was "tolerated" (though the building of stone Orthodox churches was forbidden). Hungary entered the Thirty Years' War, Royal (Habsburg) Hungary joined the Catholic side, until Transylvania joined the Protestant side.

In 1686, two years after the unsuccessful siege of Buda, a renewed European campaign was started to enter the Hungarian capital. This time, the Holy League's army was twice as large, containing over 74,000 men, including German, Croat, Dutch, Hungarian, English, Spanish, Czech, Italian, French, Burgundian, Danish and Swedish soldiers, along with other Europeans as volunteers, artilleryman, and officers, the Christian forces reconquered Buda. The second Battle of Mohács was a crushing defeat for the Turks, in the next few years, all of the former Hungarian lands, except areas near Timişoara (Temesvár), were taken from the Turks. At the end of the 17th century, Transylvania became part of Hungary again.[42] In the 1699 Treaty of Karlowitz these territorial changes were officially recognised, and in 1718 the entire Kingdom of Hungary was removed from Ottoman rule.

Concurrently, between 1604 and 1711, there was a series of anti-Austrian, and anti-Habsburg uprisings which took place in the Habsburg state of Royal Hungary (more precisely, in present-day Slovakia and in present day western and central Hungary), as well as anti-Catholic uprisings, which were to be found across the Hungarian lands. Religious protesters demanded equal rights among Christian groups. The uprisings were usually organized from Transylvania.

Ethnic aftermath of Ottoman wars

As a consequence of the constant warfare between Hungarians and Ottoman Turks, population growth was stunted and the network of medieval settlements with their urbanized bourgeois inhabitants perished. The 150 years of Turkish wars fundamentally changed the ethnic composition of Hungary. As a result of demographic losses including deportations and massacres, the number of ethnic Hungarians in existence at the end of the Turkish period was substantially diminished.[43]

Late Modern period (1700–1918)

There were a series of anti-Habsburg (i.e. anti-Austrian) and anti-Catholic (requiring equal rights and freedom for all Christian religions) uprisings between 1604 and 1711, which – with the exception of the last one – took place in Royal Hungary. The uprisings were usually organized from Transylvania. The last one was an uprising led by 'II. Rákóczi Ferenc', who after the dethronement of the Habsburgs in 1707 at the Diet of Ónód took power as the "Ruling Prince" of Hungary. The Hungarian Kuruc army lost the main battles at Battle of Trencin however there were also success actions, for example when Ádám Balogh almost captured the Austrian Emperor with Kuruc troops. When Austrians defeated the uprising in 1711, Rákóczi was in Poland. He later fled to France, finally Turkey, and lived to the end of his life (1735) in nearby Rodosto. Ladislas Ignace de Bercheny who was son of Miklós Bercsényi immigrated to France and created the first French hussar regiment. Afterward, to make further armed resistance impossible, the Austrians blew up some castles (most of the castles on the border between the now-reclaimed territories occupied earlier by the Ottomans and Royal Hungary), and allowed peasants to use the stones from most of the others as building material (the végvárs among them). The 18th century also saw one of the most famous Hungarian hussars named Michael Kovats. He created the modern US cavalry in the American Revolutionary War and is commemorated today with a statue in Charleston, North Carolina.

The Period of Reforms (1825–1848)

In the 1820s, the Emperor was forced to convene the Hungarian Diet, and thus a Reform Period began. Nevertheless, its progress was slow, because the nobles insisted on retaining their privileges (no taxation, exclusive voting rights, etc.). Therefore the achievements were mostly of national character (e.g. introduction of Hungarian as one of the official languages of the country, instead of the former Latin).

Count István Széchenyi, the most prominent statesmen of the country recognized the urgent need of modernization and their message got through. The Hungarian Parliament was reconvened in 1825 to handle financial needs. A liberal party emerged in the Diet. The party focused on providing for the peasantry in mostly symbolic ways because of their ability to understand the needs of the laborers. Lajos Kossuth emerged as leader of the lower gentry in the Parliament. Habsburg monarchs tried to preclude the industrialization of the country. A remarkable upswing started as the nation concentrated its forces on modernization even though the Habsburg monarchs obstructed all important liberal laws about the human civil and political rights and economic reforms. Many reformers (like Lajos Kossuth, Mihály Táncsics ) were imprisoned by the authorities.

Revolution, and War of Independence

On 15 March 1848 mass demonstrations in Pest and Buda enabled Hungarian reformists to push through a list of 12 demands. The Hungarian Diet took the opportunity presented by the revolution to enact a comprehensive legislative program of dozens of civil and human rights reforms, referred to as the April laws. Faced with revolution both at home and in Vienna, Austrian Emperor Ferdinand I first had to accept Hungarian demands. After the Austrian revolution was suppressed, emperor Franz Joseph replaced his epileptic uncle Ferdinand I as Emperor. Franz Joseph refused all reforms and started to arm against Hungary. A year later, in April 1849 the independent government of Hungary was established.[44] The new independent government seceded from the Austrian Empire.[45] The new government formed itself as a republic with under governor and president Lajos Kossuth and the first Prime minister, Lajos Batthyány. The House of Habsburg of the Austrian Empire was dethroned in Hungarian part of the Austrian Empire and the first Republic of Hungary was founded. The Habsburg Ruler and his advisers skilfully manipulated the Croatian, Serbian and Romanian peasantry, led by priests and officers firmly loyal to the Habsburgs, and induced them to rebel against the Hungarian government. The Hungarians were supported by the vast majority of the Slovak, German and Rusyn nationalities and by all the Jews of the kingdom, as well as by a large number of Polish, Austrian and Italian volunteers.[46] Many members of the nationalities gained coveted the highest positions within the Hungarian Army, like General János Damjanich, an ethnic Serb who became a Hungarian national hero through his command of the 3rd Hungarian Army Corps. Initially, the Hungarian forces (Honvédség) defeated Austrian armies. In July 1849 Hungarian Parliament proclaimed and enacted foremost the ethnic and minority rights in the world, but it was too late: To counter the successes of the Hungarian revolutionary army, Franz Joseph asked for help from the "Gendarme of Europe," Czar Nicholas I, whose Russian armies invaded Hungary. The huge army of the Russian Empire and the Austrian forces proved too powerful for the Hungarian army, and General Artúr Görgey surrendered in August 1849. Julius Freiherr von Haynau, the leader of the Austrian army, then became governor of Hungary for a few months and, on 6 October, ordered the execution of 13 leaders of the Hungarian army as well as Prime Minister Batthyány. Lajos Kossuth escaped into exile.

Following the war of 1848–1849, the whole country was in "passive resistance". Archduke Albrecht von Habsburg was appointed governor of the Kingdom of Hungary, and this time was remembered for Germanization pursued with the help of Czech officers.

Austria–Hungary (1867–1918)

Due to external and internal problems, reforms seemed inevitable to secure the integrity of the Habsburg Empire. Major military defeats, like the Battle of Königgrätz (1866), forced the Emperor to concede internal reforms. To appease Hungarian separatism, the Emperor made a deal with Hungary, negotiated by Ferenc Deák, called the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, by which the dual Monarchy of Austria–Hungary came into existence. The two realms were governed separately by two parliaments from two capitals, with a common monarch and common external and military policies. Economically, the empire was a customs union. The first Prime Minister of Hungary after the Compromise was Count Gyula Andrássy. The old Hungarian Constitution was restored, and Franz Joseph was crowned as King of Hungary.

In 1868, Hungarian and Croatian assembly made the Croatian–Hungarian Agreement by which Croatia was recognised as autonomous region of Holly crown.

Austria-Hungary was geographically the second largest country in Europe after the Russian Empire (239,977 sq. m in 1905 [47]), and the third most populous (after Russia and the German Empire).

Nationalists demanded education in the Magyar language, a position that united Catholics and Protestants opposed to instruction in Latin as desired by Catholic bishops. In the 1832-36 Diet the conflict between Catholic laymen and clergy sharpened considerably and a mixed commission was established. It offered the Protestants certain limited concessions. The basic issue of this religious and educational struggle was how to promote the Magyar language and Magyar nationalism and achieve more independence from German Austria.[48]

The landed nobility controlled the villages and monopolized political roles.[49] In Parliament, the magnates held life memberships in the Upper House, and the gentry dominated the Lower House and, after 1830, parliamentary life. The tension between "crown" (the German-speaking Hapsburgs in Vienna) and "country" remained a constant political fixture as the Compromise of 1867 enabled the Magyar nobility to run the country but left the Emperor with control over foreign and military policies. Conflicts between magnates and gentry appeared regarding protection against cheap food imports (1870s), the Church-state problem (1890s), and the "constitutional crisis" (1900s). The gentry gradually lost their power locally and rebuilt their political base more on office-holding rather than landownership. They depended more and more on the state apparatus and were reluctant to challenge it.[50]

Economy

The era witnessed economic development in the rural country. The formerly backwards Hungarian economy became relatively modern and industrialized by the turn of the 20th century, although agriculture remained dominant. In 1873, the old capital Buda and Óbuda (Ancient Buda) were officially merged with the third city, Pest, thus creating the new metropolis of Budapest. The dynamic Pest grew into the country's administrative, political, economic, trade and cultural hub.

Technological advancement accelerated industrialization and urbanization. The GNP per capita grew roughly 1.45% per year from 1870 to 1913. That level of growth compared very favorably to that of other European nations such as Britain (1.00%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%). The strong points of the industry were the electricity and electro-technology, telecommunication, and the transport industry: (locomotive and tram construction ship construction) The key symbols of industrialization were (at the time) the famous Ganz concern, and Tungsram Works. Many of the state institutions and the modern administrative system of Hungary were established during this period.

Due to various reasons like the policy of Magyarization [51][52] and the migration of millions, the census in 1910 (excluding Croatia), recorded the following distribution of population: Hungarian 54.5%, Romanian 16.1%, Slovak 10.7%, and German 10.4%. The largest religious denomination was the Roman Catholic (49.3%), followed by the Calvinist (14.3%), Greek Orthodox (12.8%) /Romanians Serbians Ruthenians), Greek Catholic (11.0%), Lutheran (7.1%), and Jewish (5.0%) religions. In 1910, 6.37% of the population were eligible to vote in elections due to census.[53]

World War I

After the Assassination in Sarajevo the Hungarian Prime Minister, István Tisza and his cabinet tried to avoid the breaking out of a war in Europe, but his diplomatic attempts remained unsuccessful.

Austria–Hungary drafted 9 million (fighting forces: 7,8 million) soldiers in World War I (4 million from Kingdom of Hungary). In First World War, Austria–Hungary was fighting on the side of Germany, Bulgaria and Turkey. The Central Powers conquered Serbia and Romania proclaimed war. The Central Powers later conquered Southern Romania and the Romanian capital Bucharest. On November 1916 Emperor Franz Joseph died, the new monarch Charles IV sympathized by pacifists. With great difficulty, the Central Powers stopped and repelled the attacks of the Russian Empire. The Eastern front of the Allied (Entente) Powers completely collapsed. Austria-Hungary withdrew from defeated countries. On the Italian front, the Austro-Hungarian army could not make more successful progress against Italy after January 1918. Despite great Eastern successes, Germany suffered complete defeat in the more determinant Western front. By 1918, the economic situation had deteriorated (strikes in factories were organized by leftist and pacifist movements), and uprisings in the army had become commonplace. In the capital cities (Vienna and Budapest), the Austrian and the Hungarian leftist liberal movements (the maverick parties) and their leader politicians supported and strengthened the separatism of ethnic minorities. Austria-Hungary signed general armistice in Padua on 3 November 1918. In October 1918, the personal union with Austria was dissolved.

Between the two world wars (1918–1941)

Hungarian People's Republic

In 1918, as a political result of German defeat on the Western front in World War I, the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy collapsed. French Entente troops landed in Greece to rearm the defeated Romania and Serbia, and the newly formed Czechoslovak state. Despite general armistice agreement, the Balkanian French army organized new campaigns against Hungary with the help of Czechoslovak, Romanian and Serbian governments.

Former Prime Minister István Tisza was murdered in Budapest by a gang of soldiers during Aster Revolution of October 1918. On 31 October 1918 the success of the Aster Revolution in Budapest brought the leftist liberal count Mihály Károlyi to power as Prime Minister. Károlyi was a devotee of Entente from the beginning of the war. On 13 November 1918 Charles I. surrendered his powers as King of Hungary; however, he did not abdicate, a technicality that made a return to the throne possible.[54] The First Republic was proclaimed on 16 November 1918 with Károlyi being named as president. Károlyi tried to build Hungary as the "Eastern Switzerland" and persuade nonhungarian minorities - Slovaks, Romanians, Ruthenians to stay loyal to the country, offering them autonomy. However these efforts came too late. By a notion of Woodrow Wilson's pacifism, Károlyi ordered the full disarmament of Hungarian Army. Hungary remained without national defence in the darkest hour of its history. Surrounding countries started to arm. On 5 November 1918 Serbian Army with French involvement attacked Southern parts of the country, on 8 November Czechoslovak Army attacked Northern part of Hungary, on 2 December Romanian Army started to attack the eastern (Transylvanian) parts of Hungary. The Károlyi government pronounced illegal all armed associations and proposals which wanted to defend the integrity of the country. The Károlyi government's measures failed to stem popular discontent, especially when the Entente powers began distributing slices of Hungary's traditional territory to Romania, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia, giving priority to ethno-linguistic criteria than to the historical one. French and Serbian forces occupied the southern parts of Hungary.

By February 1919 the government had lost all popular support, having failed on domestic and military fronts. On 21 March after the Entente military representative demanded more and more territorial concessions from Hungary ( Vix´s note ), Károlyi signed all concessions and resigned.

Hungarian Soviet Republic ("Republic of the Councils")

The Communist Party of Hungary, led by Béla Kun, allied itself with the Hungarian Social Democratic Party came to power and proclaimed the Hungarian Soviet Republic. Social Democrat Sándor Garbai was the official Head of government, but the Soviet Republic was de facto dominated by Béla Kun, who was in charge of foreign affairs. The Communists – "The Reds" – came to power largely thanks to being the only group with an organized fighting force, and they promised that Hungary would defend its territory without conscription. (possibly with the help of the Soviet Red Army). Hence: the Red Army of Hungary was a little voluntary army (53,000 men). Most soldiers of the Red Army were armed factory workers from Budapest. Initially, Kun's regime achieved some military successes: the Hungarian Red Army, under the lead of the genius strategist, Colonel Aurél Stromfeld, ousted Czechoslovak troops from the north and planned to march against the Romanian army in the east. In terms of domestic policy, the Communist government nationalized industrial and commercial enterprises, socialized housing, transport, banking, medicine, cultural institutions, and all landholdings of more than 400,000 square metres. The support of the Communists proved to be short-lived in Budapest. The Communists had never been popular in country towns and countryside. In the aftermath of a coup attempt, the government took a series of actions called the Red Terror, murdering several hundred people (mostly scientists and intellectuals). The Soviet Red Army was never able to aid the new Hungarian republic. Despite the great military successes against Czechoslovakian army, the Communist leaders gave back all recaptured lands. That attitude demoralized the voluntary army. The Hungarian Red Army was dissolved before it could successfully complete its campaigns. In the face of domestic backlash and an advancing Romanian force, Béla Kun and most of his comrades fled to Austria, while Budapest was occupied on 6 August. Kun and his followers took along numerous art treasures and the gold stocks of the National Bank.[55] All these events, and in particular the final military defeat, led to a deep feeling of dislike among the general population against the Soviet Union (which did not offer military assistance) and the Jews (since most members of Kun's government were Jewish, making it easy to blame the Jews for the government's mistakes).

Counterrevolution

The new fighting force in Hungary were the Conservative Royalists counter-revolutionaries – the "Whites". These, who had been organizing in Vienna and established a counter-government in Szeged, assumed power, led by István Bethlen, a Transylvanian aristocrat, and Miklós Horthy, the former commander in chief of the Austro-Hungarian Navy. The conservatives determined the Károlyi government and Communists as capital treason. Starting in Western Hungary and spreading throughout the country, a White Terror began by other half-regular and half-militarist detachments (as the police power crashed, there were no serious national regular forces and authorities), and many arrant Communists and other leftists were tortured and executed without trial. Radical Whites launched pogroms against the Jews, displayed as the cause of all territorial losses of Hungary. The most notorious commander of the Whites was Pál Prónay. The leaving Romanian army pillaged the country: livestock, machinery and agricultural products were carried to Romania in hundreds of freight cars.[56][57] On 16 November with the consent of Romanian forces, Horthy's army marched into Budapest. His government gradually restored security, stopped terror, and set up authorities, but thousands of sympathizers of the Károlyi and Kun regimes were imprisoned. Radical political movements were suppressed. In March the parliament restored the Hungarian monarchy but postponed electing a king until civil disorder had subsided. Instead, Miklos Horthy was elected Regent and was empowered, among other things, to appoint Hungary's Prime Minister, veto legislation, convene or dissolve the parliament, and command the armed forces.

Trianon Hungary and the Regency

Hungary's signing of the Treaty of Trianon on 4 June 1920 ratified the country's borders being redrawn. The territorial provisions of the treaty required Hungary to surrender more than two-thirds of its pre-war lands. However, nearly one-third of the 10 million ethnic Hungarians found themselves outside the diminished homeland.

New international borders separated Hungary's industrial base from its sources of raw materials and its former markets for agricultural and industrial products. Hungary lost 84% of its timber resources, 43% of its arable land, and 83% of its iron ore. Furthermore, post-Trianon Hungary possessed 90% of the engineering and printing industry of the Kingdom, while only 11% of timber and 16% iron was retained. In addition, 61% of arable land, 74% of public road, 65% of canals, 62% of railroads, 64% of hard surface roads, 83% of pig iron output, 55% of industrial plants, 100% of gold, silver, copper, mercury and salt mines, and most of all, 67% of credit and banking institutions of the former Kingdom of Hungary lay within the territory of Hungary's neighbors.[60][61][62]

Horthy appointed Count Pál Teleki as Prime Minister in July 1920. His government issued a numerus clausus law, limiting admission of "political insecure elements" (these were often Jews) to universities and, in order to quiet rural discontent, took initial steps towards fulfilling a promise of major land reform by dividing about 3,850 km2 from the largest estates into smallholdings. Teleki's government resigned, however, after, Charles IV, unsuccessfully attempted to retake Hungary's throne in March 1921. King Charles's return produced split parties between conservatives who favored a Habsburg restoration and nationalist right-wing radicals who supported election of a Hungarian king. Count István Bethlen, a non-affiliated right-wing member of the parliament, took advantage of this rift forming a new Party of Unity under his leadership. Horthy then appointed Bethlen Prime Minister. Charles IV died soon after he failed a second time to reclaim the throne in October 1921. (For more detail on Charles's attempts to retake the throne, see Charles IV of Hungary's conflict with Miklós Horthy.)

As Prime Minister, Bethlen dominated Hungarian politics between 1921 and 1931. He fashioned a political machine by amending the electoral law, providing jobs in the expanding bureaucracy to his supporters, and manipulating elections in rural areas. Bethlen restored order to the country by giving the radical counter-revolutionaries payoffs and government jobs in exchange for ceasing their campaign of terror against Jews and leftists. In 1921, he made a deal with the Social Democrats and trade unions (called the Bethlen-Peyer Pact), agreeing, among other things, to legalize their activities and free political prisoners in return for their pledge to refrain from spreading anti-Hungarian propaganda, calling political strikes, and organizing the peasantry. Bethlen brought Hungary into the League of Nations in 1922 and out of international isolation by signing a treaty of friendship with Italy in 1927. The revision of the Treaty of Trianon rose to the top of Hungary's political agenda and the strategy employed by Bethlen consisted of strengthening the economy and building relations with stronger nations. Revision of the treaty had such a broad backing in Hungary that Bethlen used it, at least in part, to deflect criticism of his economic, social and political policies. The Great Depression induced a drop in the standard of living and the political mood of the country shifted further towards the right. In 1932 Horthy appointed a new Prime Minister, Gyula Gömbös, that changed the course of Hungarian policy towards closer cooperation with Germany and started an effort to magyarize the few remaining ethnic minorities in Hungary. Gömbös signed a trade agreement with Germany that drew Hungary's economy out of depression but made Hungary dependent on the German economy for both raw materials and markets. Adolf Hitler appealed to Hungarian desires for territorial revisionism, while extreme right wing organizations, like the Arrow Cross Party, increasingly embraced extreme Nazi policies, including those relating to the suppression and victimization of Jews. The government passed the First Jewish Law in 1938. The law established a quota system to limit Jewish involvement in the Hungarian economy.

In 1938 became Prime Minister Béla Imrédy. Imrédy's attempts to improve Hungary's diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom initially made him very unpopular with Germany and Italy. In light of Germany's Anschluss of Austria in March, he realized that he could not afford to alienate Germany and Italy for long. In the autumn of 1938 his foreign policy became very much pro-German and pro-Italian.[63] Intent on amassing a base of power in Hungarian right wing politics, Imrédy began to suppress political rivals, so the increasingly influential Arrow Cross Party was harassed, and eventually banned by Imrédy's administration. As Imrédy drifted further to the right, he proposed that the government be reorganized along totalitarian lines and drafted a harsher Second Jewish Law. Parliament, under the new government of Pál Teleki, approved the Second Jewish Law in 1939, which greatly restricted Jewish involvement in the economy, culture and society and, significantly, defined Jews by race instead of religion. This definition significantly and negatively altered the status of those who had formerly converted from Judaism to Christianity.

World War II

Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy sought to enforce peacefully the claims of Hungarians on territories Hungary lost in 1920 with the signing of the Treaty of Trianon, and the two Vienna Awards returned parts of Czechoslovakia and Transylvania to Hungary.

On 20 November 1940 under pressure from Germany, Pál Teleki affiliated Hungary with the Tripartite Pact. In December 1940, he also signed an ephemeral "Treaty of Eternal Friendship" with Yugoslavia. A few months later, after a Yugoslavian coup threatened the success of the planned German invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa), Hitler asked the Hungarians to support his invasion of Yugoslavia. He promised to return some former Hungarian territories lost after World War I in exchange for cooperation.[54] Unable to prevent Hungary's participation in the war alongside Germany, Teleki committed suicide. The right-wing radical László Bárdossy succeeded him as Prime Minister. Eventually Hungary annexed small parts of present day Slovenia, Croatia and Serbia.

After war broke out on the Eastern Front many Hungarian officials argued for participation in the war so as not to encourage Hitler into favoring Romania in the event of border revisions in Transylvania. Hungary entered the war and on 1 July 1941 at the direction of the Germans, the Hungarian Karpat Group advanced far into southern Russia. At the Battle of Uman the Gyorshadtest participated in the encirclement of the 6th Soviet Army and the 12th Soviet Army. Twenty Soviet divisions were captured or destroyed.

Worried about Hungary's increasing reliance on Germany, Admiral Horthy forced Bárdossy to resign and replaced him with Miklós Kállay, a veteran conservative of Bethlen's government. Kállay continued Bárdossy's policy of supporting Germany against the Red Army, while he also surreptitiously entered into negotiations with the Western Powers.

During the Battle of Stalingrad, the Hungarian Second Army suffered terrible losses. Shortly after the fall of Stalingrad in January 1943, the Hungarian Second Army effectively ceased to exist as a functioning military unit.

Secret negotiations with the British and Americans continued.[63] Aware of Kállay's deceit and fearing that Hungary might conclude a separate peace, Hitler ordered Nazi troops to launch Operation Margarethe and occupy Hungary in March 1944. Döme Sztójay, an avid supporter of the Nazis, become the new Prime Minister with the aid of a Nazi military governor, Edmund Veesenmayer.

The infamous SS Colonel Adolf Eichmann went to Hungary to oversee the large-scale deportations of Jews to German death camps in occupied Poland. Between 15 May and 9 July 1944 the Hungarians deported 437,402 Jews to the Auschwitz concentration camp.[64][65]

In August 1944 Horthy replaced Sztójay with the anti-Fascist General Géza Lakatos. Under the Lakatos regime, the acting Interior Minister Béla Horváth ordered Hungarian gendarmes to prevent any Hungarian citizens from being deported.

In September 1944, Soviet forces crossed the Hungarian border. On 15 October 1944, Horthy announced that Hungary had signed an armistice with the Soviet Union. The Hungarian army ignored the armistice. The Germans launched Operation Panzerfaust and, by kidnapping his son (Miklós Horthy, Jr.), forced Horthy to abrogate the armistice, depose the Lakatos government, and name the leader of the Arrow Cross Party, Ferenc Szálasi, as Prime Minister. Szálasi became Prime Minister of a new fascist Government of National Unity and Horthy abdicated.

In cooperation with the Nazis, Szálasi restarted the deportations of Jews, particularly in Budapest. Thousands more Jews were killed by Hungarian Arrow Cross members. The retreating German army demolished the rail, road, and communications systems.

On 28 December 1944 a provisional government was formed in Hungary under acting Prime Minister Béla Miklós. Miklós and Szálasi's rival governments each claimed legitimacy: the Germans and pro-German Hungarians loyal to Szálasi fought on, as the territory effectively controlled by the Arrow Cross regime shrunk gradually. The Red Army completed the encirclement of Budapest on 29 December 1944 and the Battle of Budapest began and continued into February 1945. Most of what remained of the Hungarian First Army was destroyed about 200 miles north of Budapest between 1 January and 16 February 1945. Budapest unconditionally surrendered to the Soviet Red Army on 13 February 1945.

On 20 January 1945, representatives of the Hungarian provisional government signed an armistice in Moscow. Szálasi's government had fled the country by the end of March. Officially, Soviet operations in Hungary ended on 4 April 1945 when the last German troops were expelled. On 7 May 1945 General Alfred Jodl, the German Chief of Staff, signed the unconditional surrender of all German forces.

Hungary's World War II casualties: Tamás Stark of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences has provided the following assessment of losses from 1941 to 1945 in Hungary. Military losses were 300,000–310,000, including 110–120,000 killed in battle and 200,000 missing in action and POW in the Soviet Union. Hungarian military losses include 110,000 men who were conscripted from the annexed territories of Greater Hungary in Slovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia and the deaths of 20-25,000 Jews conscripted for Army labor units. Civilian losses of about 80,000 include 45,500 killed in the 1944–1945 military campaign and in air attacks,[66] and the genocide of Romani people of 28,000 persons.[67] Jewish Holocaust victims totaled 600,000 (300,000 in the territories annexed in 1938,1939,1940 and 1941, 200,000 in the pre-1938 countryside and 100,000 in Budapest).[68] See World War II casualties.

Post-War Communist period

Transition to Communism (1944–1949)

The Soviet Army occupied Hungary from September 1944 until April 1945. The siege of Budapest lasted almost 2 months, from December 1944 to February 1945 (the longest successful siege of any city in the entire war, including Berlin) and the city suffered widespread destruction, including all the Danube bridges which were blown up by the Germans in an effort to slow the Soviet advance.

By signing the Peace Treaty of Paris, Hungary again lost all the territories that it had gained between 1938 and 1941. Neither the Western Allies nor the Soviet Union supported any change in Hungary's pre-1938 borders, which was the primary motive behind the Hungarian involvement in the war. The Soviet Union itself annexed Sub-Carpathia (before 1938 the eastern edge of Czechoslovakia), which is today part of Ukraine.

The Treaty of Peace with Hungary signed on 10 February 1947 declared that: "The decisions of the Vienna Award of November 2, 1938, are declared null and void" and Hungarian boundaries were fixed along the former frontiers as they existed on 1 January 1938 except a minor loss of territory on the Czechoslovakian border. Many of the Communist leaders of 1919 returned from Moscow. The first major violation of civil rights was suffered by the ethnic German minority, half of which (240,000 people) were deported to Germany in 1946–1948, although the great majority of them did not support Germany and were not members of any pro-Nazi movement. There was a forced "exchange of population" between Hungary and Czechoslovakia, which involved about 70,000 Hungarians living in Slovakia and somewhat smaller numbers of ethnic Slovaks living in the territory of Hungary. Unlike the Germans, these people were allowed to carry some of their property with them.

The Soviets originally planned for a piecemeal introduction of the Communist regime in Hungary, therefore when they set up a provisional government in Debrecen on 21 December 1944, they were careful to include representatives of several moderate parties. Following the demands of the Western Allies for a democratic election, the Soviets authorized the only essentially free election in eastern Europe in November 1945 in Hungary. This was also the first election held in Hungary on the basis of universal franchise. People voted for party lists, not for individual candidates. At the elections the Independent Smallholders' Party, a center-right peasant party, won 57% of the vote. Despite the hopes of the Communists and the Soviets that the distribution of the aristocratic estates among the poor peasants would increase their popularity, the Hungarian Communist Party received only 17% of the votes. The Soviet commander in Hungary, Marshal Voroshilov, refused to allow the Smallholders' Party to form a government on their own. Under Voroshilov's pressure, the Smallholders organized a coalition government including the Communists, the Social Democrats and the National Peasant Party (a left-wing peasant party), in which the Communists held some of the key posts. On 1 February 1946 Hungary was declared a Republic, and the leader of the Smallholders, Zoltán Tildy, became President handing over the office of Prime Minister to Ferenc Nagy. Mátyás Rákosi, leader of the Communist Party, became deputy Prime Minister.

Another leading Communist, László Rajk became minister of the interior responsible for controlling law enforcement, and in this position established the security police (ÁVH). The Communists exercised constant pressure on the Smallholders both inside and outside the government, nationalizing industrial companies, banning religious civil organizations and occupying key positions in local public administration. In February 1947 the police began arresting leaders of the Smallholders Party, charging them with "conspiracy against the Republic". Several prominent figures decided to emigrate or were forced to escape abroad, including Prime Minister Ferenc Nagy in May 1947. Later Mátyás Rákosi boasted that he had dealt with his partners in the government, one by one, "cutting them off like slices of salami."

At the next parliamentary election in August 1947 the Communists committed widespread election fraud with absentee ballots (the so-called "blue slips"), but even so, they only managed to increase their share from 17% to 24% in Parliament. The Social Democrats (by this time a servile ally of the Communists) received 15% in contrast to their 17% in 1945. The Smallholders' Party lost much of its popularity and ended up with 15%, but their former voters turned towards three new center-right parties which seemed more determined to resist the Communist onslaught: their combined share of the total votes was 35%.

Faced with their second failure at the polls, the Communists changed tactics, and, under new orders from Moscow, decided to eschew democratic facades and speed up the Communist takeover. In June 1948 the Social Democratic Party was forced to "merge" with the Communist Party, creating the Hungarian Working People's Party, which was dominated by the Communists. Anti-Communist leaders of the Social Democrats, such as Károly Peyer or Anna Kéthly, were forced into exile or excluded from the party. Soon after, President Zoltán Tildy was also removed from his position, and replaced by a fully cooperative Social Democrat, Árpád Szakasits. Ultimately, all "democratic" parties were organized into a so-called People's Front in February 1949, thereby losing even the vestiges of their autonomy. The leader of the People's Front was Rákosi himself. Opposition parties were simply declared illegal and their leaders arrested or forced into exile.

On 18 August 1949 the parliament passed the new constitution of Hungary (1949/XX.) modeled after the 1936 constitution of the Soviet Union. The name of the country changed to the People's Republic of Hungary, "the country of the workers and peasants" where "every authority is held by the working people". Socialism was declared as the main goal of the nation. A new coat-of-arms was adopted with Communist symbols, such the red star, hammer and sickle.

Stalinist era (1949–1956)

Mátyás Rákosi, who as a chief secretary of the Hungarian Working People's Party was de facto the leader of Hungary, possessed practically unlimited power and demanded complete obedience from fellow members of the Party, including his two most trusted colleagues, Ernő Gerő and Mihály Farkas. All three of them returned to Hungary from Moscow, where they spent long years and had close ties to high-ranking Soviet leaders there. Their main rivals in the party were the 'Hungarian' Communists who led the illegal party during the war in Hungary, and were considerably more popular within party ranks. Their most influential leader, László Rajk, who was minister of foreign affairs at the time, was arrested in May 1949. He was accused of rather surreal crimes, such as spying for Western imperialist powers and for Yugoslavia (which was also a Communist country but in very bad relations with the Soviet Union at the time). At his trial in September 1949 he made a forced confession to be an agent of Miklós Horthy, Leon Trotsky, Josip Broz Tito and Western imperialism. He also admitted that he had taken part in a murder plot against Mátyás Rákosi and Ernő Gerő. Rajk was found guilty and executed. In the next three years, other leaders of the party deemed untrustworthy, like former Social Democrats or other Hungarian illegal Communists such as János Kádár, were also arrested and imprisoned on trumped-up charges.

The showcase trial of Rajk is considered the beginning of the worst period of the Rákosi dictatorship. Mátyás Rákosi now attempted to impose totalitarian rule on Hungary. The centrally orchestrated personality cult focused on him and Joseph Stalin soon reached unprecedented proportions. Rákosi's images and busts were everywhere, all public speakers were required to glorify his wisdom and leadership. In the meantime, the secret police, led through Gábor Péter by Rákosi himself, mercilessly persecuted all 'class enemies' and 'enemies of the people'. An estimated 2,000 people were executed and over 100,000 were imprisoned. Some 44,000 ended up in forced-labor camps, where many died due to horrible work conditions, poor food and practically no medical care. Another 15,000 people, mostly former aristocrats, industrialists, military generals and other upper-class people were deported from the capital and other cities to countryside villages where they were forced to do hard agricultural labor. These policies were opposed by some members of the Hungarian Working People's Party and around 200,000 were expelled by Rákosi from the organization.

By 1950, the state controlled most of the economy, as all large and mid-sized industrial companies, plants, mines, banks of all kind as well as all companies of retail and foreign trade were nationalized without any compensation. Slavishly following Soviet economic policies, Rákosi declared that Hungary would become a "country of iron and steel", even though Hungary lacked iron ore completely. The forced development of heavy industry served military purposes; it was meant to be preparation for the impending World War III against Western imperialism. A disproportionate amount of the country's resources were spent on building whole industrial cities and plants from scratch, while much of the country was still in ruins since the war. Traditional strengths of Hungary, such as the agricultural and textile industries were neglected.

Large agricultural latifundia were divided and distributed among poor peasants already in 1945. In agriculture, the government tried to force independent peasants to enter co-operatives in which they would become merely paid laborers, but many of them stubbornly resisted. The government retaliated with ever higher requirements of compulsory food quotas imposed on peasants' produce. Rich peasants, called 'kulaks' in Russians, were declared 'class enemies' and suffered all sorts of discrimination, including imprisonment and loss of property. With them, some of the most able farmers were removed from production. The declining agricultural output led to a constant scarcity of food, especially meat.

Rákosi rapidly expanded the education system in Hungary. This was an attempt to replace the educated class of the past by what Rákosi called a new "working intelligentsia". In addition to effects such as better education for the poor, more opportunities for working class children and increased literacy in general, this measure also included the dissemination of Communist ideology in schools and universities. Also, as part of an effort to separate the Church from the State, practically all religious schools were taken into state ownership, and religious instruction was denounced as retrograde propaganda and was gradually eliminated from schools.

The Hungarian churches were systematically intimidated. Cardinal József Mindszenty, who had bravely opposed the German Nazis and the Hungarian Fascists during the Second World War, was arrested in December 1948 and accused of treason. After five weeks under arrest (which included torture), he confessed to the charges against him and he was sentenced to life imprisonment. The Protestant churches were also purged and their leaders were replaced by those willing to remain loyal to Rákosi's government.

The new Hungarian military hastily staged public, pre-arranged trials to purge "Nazi remnants and imperialist saboteurs". Several officers were sentenced to death and executed in 1951, including Lajos Toth, a 28 victory-scoring fighter ace of World War II Royal Hungarian Air Force, who had voluntarily returned from US captivity to help revive Hungarian aviation. The victims were cleared posthumously following the fall of communism.

Preparations for a show trial started in Budapest in 1953[69] to prove that Raoul Wallenberg had not been dragged off in 1945 to the Soviet Union but was the victim of cosmopolitan Zionists. For the purposes of this show trial, three Jewish leaders as well as two would-be "eyewitnesses" were arrested and interrogated by torture. The show trial was initiated in Moscow, following Stalin's anti-Zionist campaign. After the death of Stalin and Lavrentiy Beria, the preparations for the trial were stopped and the arrested persons were released.

Rákosi had great difficulties managing the economy and the people of Hungary saw living standards fall. Although his government became increasingly unpopular, he had a firm grip on power until Stalin died on 5 March 1953 when a confused power struggle began in Moscow. Some of the Soviet leaders perceived the unpopularity of the Hungarian regime and ordered Rákosi to give up his position as Prime Minister in favor of another former Communist-in-exile in Moscow, Imre Nagy, who was Rákosi's chief opponent in the party. Rákosi, however, retained his position as general secretary of the Hungarian Working People's Party and over the next three years the two men became involved in a bitter struggle for power.

As Hungary's new Prime Minister, Imre Nagy slightly relaxed state control over the economy and the mass media and encouraged public discussion on political and economic reform. In order to improve the general supply, he increase the production and distribution of consumer goods and reduced the tax and quota burdens of the peasants. Nagy also closed forced-labor camps, released most of the political prisoners - the Communists were allowed back into Party ranks -, and reined in the secret police, whose hated head, Gábor Péter, was convicted and imprisoned in 1954. All these rather moderate reforms earned him widespread popularity in the country, especially among the peasantry and the left-wing intellectuals.

Following a turn in Moscow, where Malenkov, Nagy's primary patron lost the power struggle against Khrushchev, Mátyás Rákosi started a counterattack on Nagy. On March 9, 1955, the Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party condemned Nagy for "rightist deviation". Hungarian newspapers joined the attacks and Nagy was accused of being responsible for the country's economic problems and on 18 April he was dismissed from his post by a unanimous vote of the National Assembly. Soon after, Nagy was even excluded from the Party and temporarily retired from politics. Rákosi once again became the unchallenged leader of Hungary.

Rákosi's second reign, however, did not last long. His power was undermined by a speech made by Nikita Khrushchev in February 1956, in which he denounced the policies of Joseph Stalin and his followers in eastern Europe, especially the attacks on Yugoslavia and the cult of personality. On 18 July 1956 visiting Soviet leaders removed Rákosi from all his positions and he boarded a plane bound for the Soviet Union, never to return to Hungary. But the Soviets made a major mistake by the appointment of his close friend and ally, Ernő Gerő, as his successor, who was equally unpopular and shared responsibility for most of Rákosi's crimes.

The fall of Rákosi was followed by a flurry of reform agitation both inside and outside the Party. László Rajk and his fellow victims of the showcase trial of 1949 were cleared of all charges, and on 6 October 1956, the Party authorized a reburial, which was attended by tens of thousands of people and became a silent demonstration against the crimes of the regime. On 13 October it was announced that Imre Nagy had been reinstated as a member of the party.

1956 Revolution

On 23 October 1956 a peaceful student demonstration in Budapest produced a list of 16 demands for reform and greater political freedom. As the students attempted to broadcast these demands, police made some arrests and tried to disperse the crowd with tear gas. When the students attempted to free those arrested, the police opened fire on the crowd, setting off a chain of events which led to the Hungarian Revolution.

That night, commissioned officers and soldiers joined the students on the streets of Budapest. Stalin's statue was brought down and the protesters chanted "Russians go home", "Away with Gerő" and "Long Live Nagy". The Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party responded to these developments by requesting Soviet military intervention and deciding that Imre Nagy should become head of a new government. Soviet tanks entered Budapest at 2 a.m. on 24 October.

On 25 October Soviet tanks opened fire on protesters in Parliament Square. One journalist at the scene saw 12 dead bodies and estimated that 170 had been wounded. Shocked by these events the Central Committee of the Hungarian Working People's Party forced Ernő Gerő to resign from office and replaced him with János Kádár.

Imre Nagy now went on Radio Kossuth and announced he had taken over the leadership of the Government as Chairman of the Council of Ministers." He also promised "the far-reaching democratization of Hungarian public life, the realization of a Hungarian road to socialism in accord with our own national characteristics, and the realization of our lofty national aim: the radical improvement of the workers' living conditions."

On 28 October Nagy and a group of his supporters, including János Kádár, Géza Losonczy, Antal Apró, Károly Kiss, Ferenc Münnich and Zoltán Szabó, managed to take control of the Hungarian Working People's Party. At the same time revolutionary workers' councils and local national committees were formed all over Hungary.

The change of leadership in the party was reflected in the articles of the government newspaper, Szabad Nép (i.e. Free People). On 29 October the newspaper welcomed the new government and openly criticized Soviet attempts to influence the political situation in Hungary. This view was supported by Radio Miskolc that called for the immediate withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country.

On 30 October Imre Nagy announced that he was freeing Cardinal József Mindszenty and other political prisoners. He also informed the people that his government intends to abolish the one-party state. This was followed by statements of Zoltán Tildy, Anna Kéthly and Ferenc Farkas concerning the restitution of the Smallholders Party, the Social Democratic Party and the Petőfi (former Peasants) Party.