Charlemagne: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

Mr Stephen (talk | contribs) clean up, straight quotes, ellipsis format, ISBN format, format for page/pages using AWB (8853) |

|||

| Line 94: | Line 94: | ||

====Place of birth==== |

====Place of birth==== |

||

[[File:Chaussée-Brunehault.jpg|thumb|255px|Roman road connecting Tongeren to the Herstal region. Jupille and Herstal, near Liege, are located in the lower right corner.]] |

[[File:Chaussée-Brunehault.jpg|thumb|255px|Roman road connecting Tongeren to the Herstal region. Jupille and Herstal, near Liege, are located in the lower right corner.]] |

||

Charlemagne was most likely born in [[Herstal]], [[Wallonia]], where his father was born, a town close to [[Liège (city)|Liège]] in modern day [[Belgium]].<ref>{{cite book | title=Belgian life in town and country | first=Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh | last=Boulger | location=New York; London | publisher=G.P. Putnam's sons | year=1904 | pages=186–188}}</ref> The [[Merovingians]] had a number of hunting villas in the vicinity. Liège is close to the region from where both the |

Charlemagne was most likely born in [[Herstal]], [[Wallonia]], where his father was born, a town close to [[Liège (city)|Liège]] in modern day [[Belgium]].<ref>{{cite book | title=Belgian life in town and country | first=Demetrius Charles de Kavanagh | last=Boulger | location=New York; London | publisher=G.P. Putnam's sons | year=1904 | pages=186–188}}</ref> The [[Merovingians]] had a number of hunting villas in the vicinity. Liège is close to the region from where both the Spartan and Athenian families originated. He went to live in his father's villa in [[Jupille]] when he was around seven, which caused Jupille to be listed as a possible place of birth in almost every history book. Other cities have been suggested, including [[Aachen]], [[Düren]], [[Gauting]], [[Mürlenbach]],<ref>http://www.route-gottfried-von-bouillon.de/index.php?rid=1307&cid=5&area=content</ref> and [[Prüm]]. No definitive evidence as to which is the right candidate exists. |

||

Charlemagne was the eldest child of [[Pepin the Short]] (714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife [[Bertrada of Laon]] (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of [[Caribert of Laon]] and [[Bertrada of Cologne]]. Records name only [[Carloman I, King of the Franks|Carloman]], [[Gisela (daughter of Pepin the Short)|Gisela]], and three short-lived children named Pepin, Chrothais and Adelais as his younger siblings. |

Charlemagne was the eldest child of [[Pepin the Short]] (714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife [[Bertrada of Laon]] (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of [[Caribert of Laon]] and [[Bertrada of Cologne]]. Records name only [[Carloman I, King of the Franks|Carloman]], [[Gisela (daughter of Pepin the Short)|Gisela]], and three short-lived children named Pepin, Chrothais and Adelais as his younger siblings. |

||

Revision as of 21:23, 28 March 2013

| Charles the Great | |

|---|---|

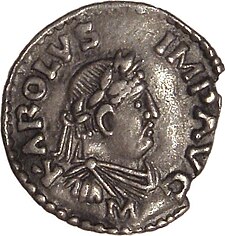

A coin of Charlemagne with the inscription KAROLVS IMP AVG (Karolus Imperator Augustus) | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | |

| Reign | December 25, 800 – January 28, 814 |

| Coronation | December 25, 800 Old St. Peter's Basilica, Rome |

| Predecessor | Position Established |

| Successor | Louis I |

| King of the Lombards | |

| Reign | July 10, 774 – January 28, 814 |

| Coronation | July 10, 774 Pavia |

| Predecessor | Desiderius |

| Successor | Louis I |

| King of the Franks | |

| Reign | October 9, 768 – January 28, 814 |

| Coronation | October 9, 768 Noyon |

| Predecessor | Pepin the Short |

| Successor | Louis I |

| Born | 2 April 742 Liège, Frankish Kingdom |

| Died | 28 January 814 (aged 71) Aachen, Holy Roman Empire |

| Burial | |

| Spouses |

|

| Issue Among others | |

| House | Carolingian |

| Father | Pepin the Short |

| Mother | Bertrada of Laon |

| Religion | Roman Catholicism |

| Carolingian dynasty |

|---|

|

Charlemagne (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈʃɑːrl[invalid input: 'ɨ']meɪn/; 2 April 742 – 28 January 814), also known as Charles the Great (German: Karl der Große;[1] Template:Lang-la) or Charles I, was the King of the Franks from 768, the King of Italy from 774, the first Holy Roman Emperor, and the first emperor in western Europe since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire three centuries earlier.

The oldest son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon, Charlemagne became king in 768 following the death of his father. He was initially co-ruler with his brother Carloman I. Carloman's sudden death in 771 under unexplained circumstances left Charlemagne as the undisputed ruler of the Frankish Kingdom. Through his military conquests, he subdued the Saxons and the Bavarians and pushed his frontier into Spain. He expanded his kingdom into an empire that incorporated much of Western and Central Europe.

Charlemagne continued his father's policy towards the papacy and became its protector, removing the Lombards from power in Italy, and leading an incursion into Muslim Spain. He also campaigned against the peoples to his east, forcibly Christianizing them along the way (especially the Saxons), eventually subjecting them to his rule after a protracted war. Charlemagne reached the height of his power in 800 when he was crowned as "Emperor" by Pope Leo III on Christmas Day.

Called the "Father of Europe" (pater Europae),[2] Charlemagne's empire united most of Western Europe for the first time since the Roman Empire. His rule spurred the Carolingian Renaissance, a revival of art, religion, and culture through the medium of the Catholic Church. Through his foreign conquests and internal reforms, Charlemagne encouraged the formation of a common European identity.[3][4] Both the French and German monarchies considered their kingdoms to be descendants of Charlemagne's empire.

Charlemagne died in 814 after having ruled as Emperor for just over thirteen years. He was laid to rest in his imperial capital of Aachen in today's Germany. His son Louis the Pious succeeded him as Emperor.

Political background

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2012) |

By the 6th century, the western Germanic Franks had been Christianised, and Francia, ruled by the Merovingians, was the most powerful of the kingdoms that succeeded the Western Roman Empire. Following the Battle of Tertry, however, the Merovingians declined into a state of powerlessness, for which they have been dubbed the rois fainéants ("do-nothing kings"). Almost all government powers of any consequence were exercised by their chief officer, the mayor of the palace.

In 687, Pippin of Herstal, mayor of the palace of Austrasia, ended the strife between various kings and their mayors with his victory at Tertry and became the sole governor of the entire Frankish kingdom. Pippin himself was the grandson of two of the most important figures of the Austrasian Kingdom, Saint Arnulf of Metz and Pippin of Landen. Pippin the Middle was eventually succeeded by his illegitimate son Charles, later known as Charles Martel.

After 737, Charles governed the Franks without a king on the throne but declined to call himself king. Charles was succeeded in 741 by his sons Carloman and Pepin the Short, the father of Charlemagne. To curb separatism in the periphery of the realm, in 743 the brothers placed on the throne Childeric III, who was to be the last Merovingian king.

After Carloman resigned office in 746 to enter the church by preference as a monk, Pepin brought the question of the kingship before Pope Zachary, asking whether it was logical for a king to have no royal power. The pope handed down his decision in 749. He decreed that it was better for Pepin, who had the powers of high office as Mayor, to be called king, so as not to confuse the hierarchy. He therefore ordered him to become true king.

In 750, Pepin was elected by an assembly of the Franks, anointed by the archbishop, and then raised to the office of king. Branding Childeric III as "the false king," the Pope ordered him into a monastery. Thus was the Merovingian dynasty replaced by the Carolingian dynasty, named after Pepin's father, Charles Martel.

In 753 Pope Stephen II fled from Italy to Francia appealing for assistance for the rights of St. Peter to Pepin. He was supported in this appeal by Carloman, Charles' brother. In return the pope could only provide legitimacy, which he did by again anointing and confirming Pepin, this time adding his young sons Carolus and Carloman to the royal patrimony, now heirs to the great realm that already covered most of western and central Europe. In 754 Pepin accepted the Pope's invitation to visit Italy on behalf of St. Peter's rights, dealing successfully with the Lombards.[5]

Under the Carolingians, the Frankish kingdom spread to encompass an area including most of Western Europe; the division of the kingdom formed the bases for modern France and Germany.[6] The religious, political, and artistic evolutions originating from a centrally positioned Francia made a defining imprint on the whole of Europe.

Rise to power

Early life

Date of birth

The most likely date of Charlemagne's birth is reconstructed from a number of sources. The date of 742—calculated from Einhard's date of death of January 814 at age 72—suffers from the defect of being two years before the marriage of his parents in 744. The year given in the Annales Petaviani, 747, would be more likely, except that it contradicts Einhard and a few other sources in making Charlemagne less than a septuagenarian at his death. The month and day of April 2 is established by a calendar from Lorsch Abbey.[7]

In 747, that day fell on Easter, a coincidence that would have been remembered but was not. If Easter was being used as the beginning of the calendar year, then April 2, 747 could have been, by modern reckoning, April 2, 748 (not on Easter). The date favored by the preponderance of evidence is April 2, 742, based on the septuagenarian age at death.[7] This date would appear to support an initial illegitimacy of birth, which is not, however, mentioned by Einhard.

Place of birth

Charlemagne was most likely born in Herstal, Wallonia, where his father was born, a town close to Liège in modern day Belgium.[8] The Merovingians had a number of hunting villas in the vicinity. Liège is close to the region from where both the Spartan and Athenian families originated. He went to live in his father's villa in Jupille when he was around seven, which caused Jupille to be listed as a possible place of birth in almost every history book. Other cities have been suggested, including Aachen, Düren, Gauting, Mürlenbach,[9] and Prüm. No definitive evidence as to which is the right candidate exists. Charlemagne was the eldest child of Pepin the Short (714 – 24 September 768, reigned from 751) and his wife Bertrada of Laon (720 – 12 July 783), daughter of Caribert of Laon and Bertrada of Cologne. Records name only Carloman, Gisela, and three short-lived children named Pepin, Chrothais and Adelais as his younger siblings.

It would be folly, I think, to write a word concerning Charles' birth and infancy, or even his boyhood, for nothing has ever been written on the subject, and there is no one alive now who can give information on it. Accordingly, I determined to pass that by as unknown, and to proceed at once to treat of his character, his deed, and such other facts of his life as are worth telling and setting forth, and shall first give an account of his deed at home and abroad, then of his character and pursuits, and lastly of his administration and death, omitting nothing worth knowing or necessary to know.

The ambiguous high office

The most powerful officers of the Frankish people, the Mayor of the Palace (Maior Domus) and one or more kings (rex, reges), were appointed by election of the people; that is, no regular elections were held, but they were held as required to elect officers ad quos summa imperii pertinebat, "to whom the highest matters of state pertained." Evidently interim decisions could be made by the Pope, which ultimately needed to be ratified using an assembly of the people, which met once a year.[11]

Before he was elected king in 750, Pepin the Short was initially a Mayor, a high office he held "as though hereditary" (velut hereditario fungebatur). Einhard explains that "the honor" was usually "given by the people" to the distinguished, but Pepin the Great and his brother Carloman the wise received it as though hereditary, as did their father, Charles Martel. There was, however, a certain ambiguity about quasi-inheritance. The office was treated as joint property: one Mayorship held by two brothers jointly.[12] Each, however, had his own geographic jurisdiction. When Carloman decided to resign, becoming ultimately a Benedictine at Monte Cassino,[13] the question of the disposition of his quasi-share was settled by the pope. He converted the Mayorship into a Kingship and awarded the joint property to Pepin, who now had the full right to pass it on by inheritance.[14]

This decision was not accepted by all members of the family. Carloman had consented to the temporary tenancy of his own share, which he intended to pass on to his own son, Drogo, when the inheritance should be settled at someone's death. By the Pope's decision, in which Pepin had a hand, Drogo was to be disqualified as an heir in favor of his cousin Charles. He took up arms in opposition to the decision and was joined by Grifo, a half-brother of Pepin and Carloman, who had been given a share by Charles Martel, but was stripped of it and held under loose arrest by his half-brothers after an attempt to seize their shares by military action. By 753 all was over. Grifo perished in combat in the Battle of Saint-Jean-de-Maurienne while Drogo was hunted down and taken into custody.[15]

On the death of Pepin, September 24, 768, the kingship passed jointly to his sons, "with divine assent" (divino nutu).[14] According to the Life, Pepin died in Paris. The Franks "in general assembly" (generali conventu) gave them both the rank of king (reges) but "partitioned the whole body of the kingdom equally" (totum regni corpus ex aequo partirentur). The annals[16] tell a slightly different version. The king died at St. Denis, which is, however, still in Paris. The two "lords" (domni) were "elevated to kingship" (elevati sunt in regnum), Carolus on October 9 in Noyon, Carloman on an unspecified date in Soissons. If born in 742, Carolus was 26 years old, but he had been campaigning at his father's right hand for several years, which may help to account for his military skill and genius. Carloman was 17.

The language in either case suggests that there were not two inheritances, which would have created distinct kings ruling over distinct kingdoms, but a single joint inheritance and a joint kingship tenanted by two equal kings, Charles and his brother Carloman. As before, distinct jurisdictions were awarded. Charles received Pepin's original share as Mayor: the outer parts of the kingdom bordering on the sea, namely Neustria, western Aquitaine, and the northern parts of Austrasia; while Carloman was awarded his uncle's former share, the inner parts: southern Austrasia, Septimania, eastern Aquitaine, Burgundy, Provence, and Swabia, lands bordering Italy. The question whether these jurisdictions were joint shares reverting to the other brother if one brother died or were inherited property passed on to the descendants of the brother who died was never definitely settled by the Frankish people. It came up repeatedly over the succeeding decades until the grandsons of Charlemagne created distinct sovereign kingdoms.

Aquitanian rebellion

An inheritance in the countries formerly under Roman law (ius or iustitia) represented not only a transmission of the properties and privileges but also the encumbrances and obligations attached to the inheritance. Pepin at his death had been in process of building an empire, a difficult task:[17]

"In those times, to build a kingdom from an aggregation of small states was itself no great difficulty ... But to keep the state intact after it had been formed was a colossal task ... Each of the minor states ... had its little sovereign ... who ... gave himself chiefly to ... plotting, pillaging and fighting."

Formation of a new Aquitania

Aquitania under Rome had been in southern Gaul, Romanized and speaking a Romance language. Similarly Hispania had been populated by peoples who spoke various languages, including Celtic, but the area was now populated entirely by Romance language speakers. Between Aquitania and Hispania were the Euskaldunak, Latinized to Vascones, or Basques,[18] living in Basque country, Vasconia, which extended, according to the distributions of place names attributable to the Basques, most densely in the western Pyrenees but also as far south as the upper Ebro River in Spain and as far north as the Garonne River in France.[19] The French name, Gascony, derives from Vasconia. The Romans were never able to entirely subject Vasconia. The parts they did, in which they placed the region's first cities, were sources of legions in the Roman army valued for their fighting abilities. The border with Aquitania was Toulouse.

The Romans after the fall of their empire were replaced by the Visigoths in Spain and the Franks and Visigoths to the north. Although they had the authority of state, these Germanic tribes were thinly settled at best. They did not keep their languages long but were assimilated to the Romance-speaking prior populations. Romance was still spoken in Toulouse and to the east as well as on the Ebro. These authorities maintained relationships with the Basques that were fully as combative as the previous had been; moreover, the Basques on the whole had the upper hand. They began to raid and pillage to the north and east of their borders into territory then ruled by the Merovingians. They took slaves from the north and sold them to the south. Army after army was sent by the Franks. If the Basques could not win they retreated into the mountains. In 635 a Frankish column under Arnebert was massacred in the Haute Soule, a mountain valley.[20]

At about 660 the Duchy of Vasconia united with the Duchy of Aquitania to form a single kingdom under Felix of Aquitaine, governing from Toulouse. This was a joint kingship with a 28-year-old Basque king, Lupus I.[21] The kingdom was sovereign and independent. On the one hand Vasconia gave up predation to become a player on the field of European politics. On the other, whatever arrangements Felix had made with the weak Merovingians were null and void. At Felix's death in 670 the joint property of the kingship reverted entirely to Lupus. As the Basques had no law of joint inheritance, but practiced primogeniture, Lupus in effect founded a hereditary dynasty of Basque kings of an expanded Aquitania.[22]

Acquisition of Aquitania by the Carolingians

The Latin chronicles on the end of Visigothic Hispania leave much to be desired, such as identification of characters, filling in the gaps, and reconciliation of numerous contradictions.[23] The Saracen (Muslim) sources, however, present a more coherent view, such as in the Ta'rikh iftitah al-Andalus ("History of the Conquest of al-Andalus") by Ibn al-Qūṭiyya (a name meaning "the son of the Gothic woman," referring to the granddaughter of the last king of all Visigothic Spain, who married a Saracen). Ibn al-Qūṭiyya, who had another, much longer name, must have been relying to some degree on family oral tradition.

According to Ibn al-Qūṭiyya,[24] the last Visigothic king of a united Hispania died before his three sons, Almund, Romulo, and Ardabast, reached majority. Their mother was regent at Toledo, but Roderic, army chief of staff, staged a rebellion, capturing Cordova. Of all the possible outcomes, he chose to impose a joint rule over distinct jurisdictions on the true heirs. Evidence of a division of some sort can be found in the distribution of coins imprinted with the name of each king and in the king lists.[25] Wittiza is succeeded by Roderic, who reigned for seven and a half years, followed by a certain Achila (Aquila), who reigned three and a half years. If the reigns of both terminated with the incursion of the Saracens, then Roderic appears to have reigned a few years before the majority of Achila. The latter's kingdom is securely placed to the northeast, while Roderic seems to have taken the rest, notably Portugal.

Achila is undoubtedly Achila II of the coins and chronicles, who is stated by some chronicles to have been the son of Wittiza. How he fits into the Gothic woman's family tree is a problem. A scribal error in the transmission of her son's manuscript has been postulated: w.q.l.h for Waqla becomes r.m.l.h for Rumulu (Arabic like Hebrew writes only the consonants). Ardabast is generally identified with Ardo king of Septimania, 713–720.[26] The location of the share of Almun, or Olemundo, has not survived, but that he had one is assured by subsequent events.

In the account, a Christian merchant, Julian, left his daughter in the guardianship of Roderic (her mother had just died) while he conducted some business on Roderic's request in North Africa. Returning to find his daughter had been seduced by Roderic he simulated nonchalance and acceptance of that event, convincing Roderic to send him back on more business. Arriving there, however, he went to Tariq ibn Ziyad and convinced him to invade al-Andalus. En route the prophet Mohammed appeared to Tariq in a dream at the head of an army, telling him to go on. When the Saracens had landed in southern Spain Roderic establishing a base at Cordova reached out to the three sons of Wittiza asking for assistance in the common defense. The three arrived but not even daring to enter Cordova they sent to Tariq stating that Roderic was no better than a dog and offering submission and support in return for keeping their ancestral lands and privileges.[27] The offer having been accepted Roderic was defeated at the Battle of Guadalete. It is not clear whether the royal Goths fought against him or simply withheld troops. "Weighed down with weapons he threw himself into the water and was never found."

The three royals travelled to Damascus to confirm their submissions:[28] "Aquila was nominated king of the Goths but in 714 he traveled with his brothers to Damascus and sold the kingdom to Caliph Walid I (705–15) for lands and money." Ardo went on as client-king in Provence. On the death of Almund he appropriated the latter's share of the joint property against the will of the children, who went to Syria to appeal the case. The Saracens moved against Ardo. The boys never recovered the land. One became a Christian bishop. The daughter, Sarah, accepted an arranged marriage with a Saracen, becoming known as "the Gothic woman." She played an important role subsequently in Moorish Spain.

The Saracens crossed the mountains to claim Ardo's Septimania, only to encounter the Basque dynasty of Aquitania, always the allies of the Goths. Odo the Great of Aquitania was at first victorious at the Battle of Bordeaux in 721.[29] Saracen troops gradually massed in Septimania and in 732 advanced into Vasconia, and Odo was defeated at the Battle of the River Garonne. They took Bordeaux and were advancing toward Tours when Odo, powerless to stop them, appealed to his arch-enemy, Charles Martel, mayor of the Franks. In one of the first of the lightning marches for which the Carolingian kings became famous, Charles and his army appeared in the path of the Saracens between Tours and Poitiers, and in the Battle of Tours settled the question of the Saracen advance into Europe. The Moors were defeated so conclusively that they retreated across the mountains, never to return, leaving Septimania to become part of Francia. Odo also had to pay the price of incorporation into Charles's kingdom, a decision that was repugnant to him and also to his heirs.

Loss and recovery of Aquitania

After the death of his son, Hunald allied himself with free Lombardy. However, Odo had ambiguously left the kingdom jointly to his two sons, Hunald and Hatto. The latter, loyal to Francia, now went to war with his brother over full possession. Victorious, Hunald blinded and imprisoned his brother, only to be so stricken by conscience that he resigned and entered the church as a monk to do penance according to Carolingian sources.[30] His son Waifer took an early inheritance, becoming duke of Aquitania, and ratified the alliance with Lombardy. Waifer decided to honor it, repeating his father's decision, which he justified by arguing that any agreements with Charles Martel became invalid on Martel's death. Since Aquitania was now Pepin's inheritance,[clarification needed] according to some the latter and his son, the young Charles, hunted down Waifer, who could only conduct a guerrilla war, and executed him.[31]

Among the contingents of the Frankish army were Bavarians under Tassilo III, Duke of Bavaria, an Agilofing, the hereditary Bavarian royal family. Grifo had installed himself as Duke of Bavaria, but Pepin replaced him with a member of the royal family yet a child, Tassilo, whose protector he had become after the death of his father. The loyalty of the Agilolfings was perpetually in question, but Pepin exacted numerous oaths of loyalty from Tassilo. However, the latter had married Liutperga, a daughter of Desiderius, king of Lombardy. At a critical point in the campaign Tassilo with all his Bavarians left the field. Out of reach of Pepin, he repudiated all loyalty to Francia.[32] Pepin had no chance to respond as he grew ill and within a few weeks after the execution of Waifer died himself.

The first event of the brothers' reign was the uprising of the Aquitainians and Gascons, in 769, in that territory split between the two kings. One year before, Pepin had finally defeated Waifer, Duke of Aquitaine, after waging a destructive, ten-year war against Aquitaine. Now, one Hunald (seemingly other than Hunald the duke) led the Aquitainians as far north as Angoulême. Charles met Carloman, but Carloman refused to participate and returned to Burgundy. Charles went to war, leading an army to Bordeaux, where he set up a fort at Fronsac. Hunald was forced to flee to the court of Duke Lupus II of Gascony. Lupus, fearing Charles, turned Hunald over in exchange for peace, and he was put in a monastery. Gascon lords also surrendered, and Aquitaine and Gascony were finally fully subdued by the Franks.

Union perforce

The brothers maintained lukewarm relations with the assistance of their mother Bertrada, but in 770 Charles signed a treaty with Duke Tassilo III of Bavaria and married a Lombard Princess (commonly known today as Desiderata), the daughter of King Desiderius, to surround Carloman with his own allies. Though Pope Stephen III first opposed the marriage with the Lombard princess, he would soon have little to fear from a Frankish-Lombard alliance.

Less than a year after his marriage, Charlemagne repudiated Desiderata and quickly married a 13-year-old Swabian named Hildegard. The repudiated Desiderata returned to her father's court at Pavia. Her father's wrath was now aroused, and he would have gladly allied with Carloman to defeat Charles. Before any open hostilities could be declared, however, Carloman died on December 5, 771, seemingly of natural causes. Carloman's widow Gerberga fled to Desiderius' court in Lombardy with her sons for protection.

Italian campaigns

Conquest of Lombardy

At his succession in 772, Pope Adrian I demanded the return of certain cities in the former exarchate of Ravenna in accordance with a promise at the succession of Desiderius. Instead, Desiderius took over certain papal cities and invaded the Pentapolis, heading for Rome. Adrian sent embassies to Charlemagne in autumn requesting he enforce the policies of his father, Pepin. Desiderius sent his own embassies denying the pope's charges. The embassies both met at Thionville, and Charlemagne upheld the pope's side. Charlemagne promptly demanded what the pope had demanded, and Desiderius promptly swore never to comply. Charlemagne and his uncle Bernard crossed the Alps in 773 and chased the Lombards back to Pavia, which they then besieged. Charlemagne temporarily left the siege to deal with Adelchis, son of Desiderius, who was raising an army at Verona. The young prince was chased to the Adriatic littoral, and he fled to Constantinople to plead for assistance from Constantine V, who was waging war with Bulgaria.

The siege lasted until the spring of 774, when Charlemagne visited the pope in Rome. There he confirmed his father's grants of land, with some later chronicles claiming—falsely—that he also expanded them, granting Tuscany, Emilia, Venice, and Corsica. The pope granted him the title patrician. He then returned to Pavia, where the Lombards were on the verge of surrendering.

In return for their lives, the Lombards surrendered and opened the gates in early summer. Desiderius was sent to the abbey of Corbie, and his son Adelchis died in Constantinople a patrician. Charles, unusually, had himself crowned with the Iron Crown and made the magnates of Lombardy do homage to him at Pavia. Only Duke Arechis II of Benevento refused to submit and proclaimed independence. Charlemagne was then master of Italy as king of the Lombards. He left Italy with a garrison in Pavia and a few Frankish counts in place the same year.

There was still instability, however, in Italy. In 776, Dukes Hrodgaud of Friuli and Hildeprand of Spoleto rebelled. Charlemagne rushed back from Saxony and defeated the duke of Friuli in battle; the duke was slain. The duke of Spoleto signed a treaty. Their co-conspirator, Arechis, was not subdued, and Adelchis, their candidate in Byzantium, never left that city. Northern Italy was now faithfully his.

Southern Italy

In 787 Charlemagne directed his attention toward the Duchy of Benevento, where Arechis was reigning independently. Charlemagne besieged Salerno, and Arechis submitted to vassalage. However, with his death in 792, Benevento again proclaimed independence under his son Grimoald III. Grimoald was attacked by armies of Charles or his sons many times, but Charlemagne himself never returned to the Mezzogiorno, and Grimoald never was forced to surrender to Frankish suzerainty.

Charles and his children

During the first peace of any substantial length (780–782), Charles began to appoint his sons to positions of authority within the realm, in the tradition of the kings and mayors of the past. In 781, he made his two younger sons kings, having them crowned by the Pope. The elder of these two, Carloman, was made king of Italy, taking the Iron Crown which his father had first worn in 774, and in the same ceremony was renamed "Pippin." The younger of the two, Louis, became king of Aquitaine. Charlemagne ordered Pippin and Louis to be raised in the customs of their kingdoms, and he gave their regents some control of their subkingdoms, but real power was always in his hands, though he intended his sons to inherit their realms some day. Nor did he tolerate insubordination in his sons: in 792, he banished his eldest, though possibly illegitimate, son, Pippin the Hunchback, to the monastery of Prüm, because the young man had joined a rebellion against him.

Charles was determined to have his children educated, including his daughters, as he himself was not. His children were taught all the arts, and his daughters were learned in the way of being a woman. His sons took archery, horsemanship, and other outdoor activities.

The sons fought many wars on behalf of their father when they came of age. Charles was mostly preoccupied with the Bretons, whose border he shared and who insurrected on at least two occasions and were easily put down, but he was also sent against the Saxons on multiple occasions. In 805 and 806, he was sent into the Böhmerwald (modern Bohemia) to deal with the Slavs living there (Bohemian tribes, ancestors of the modern Czechs). He subjected them to Frankish authority and devastated the valley of the Elbe, forcing a tribute on them. Pippin had to hold the Avar and Beneventan borders but also fought the Slavs to his north. He was uniquely poised to fight the Byzantine Empire when finally that conflict arose after Charlemagne's imperial coronation and a Venetian rebellion. Finally, Louis was in charge of the Spanish March and also went to southern Italy to fight the duke of Benevento on at least one occasion. He took Barcelona in a great siege in 797 (see below).

Charlemagne's attitude toward his daughters has been the subject of much discussion. He kept them at home with him and refused to allow them to contract sacramental marriages – possibly to prevent the creation of cadet branches of the family to challenge the main line, as had been the case with Tassilo of Bavaria – yet he tolerated their extramarital relationships, even rewarding their common-law husbands, and treasured the illegitimate grandchildren they produced for him. He also, apparently, refused to believe stories of their wild behavior. After his death the surviving daughters were banished from the court by their brother, the pious Louis, to take up residence in the convents they had been bequeathed by their father. At least one of them, Bertha, had a recognised relationship, if not a marriage, with Angilbert, a member of Charlemagne's court circle.

Carolingian expansion to the south

Vasconia and the Pyrenees

The destructive war led by Pepin in Aquitaine, although brought to a satisfactory conclusion for the Franks, proved the Frankish power structure south of the Loire was feeble and unreliable. After the defeat and death of Waifer of Aquitaine in 768, while Aquitaine submitted again to the Carolingian dynasty, a new rebellion broke out in 769 led by Hunald II, maybe son of Waifer. He took refuge with the ally duke Lupus II of Gascony, but probably out of fear of Charlemagne's reprisal, handed him over to the new King of the Franks besides pledging loyalty to him, which seemed to confirm the peace in the Basque area south of the Garonne.

However, wary of new Basque uprisings, Charlemagne seems to have tried to diminish duke Lupus's power by appointing a certain Seguin as count of Bordeaux (778) and other counts of Frankish background in bordering areas (Toulouse, County of Fézensac), a decision that seriously undermined the authority of the duke of Gascony (Vasconia). The Basque duke in turn seems to have contributed decisively or schemed the Battle of Roncevaux Pass (referred to as "Basque treachery"). The defeat of Charlemagne's army in Roncevaux (778) confirmed him in his determination to rule directly by establishing the Kingdom of Aquitaine (son Louis the Pious proclaimed first king) based on a power base of Frankish officials, distributing lands among colonisers and allocating lands to the Church, which he took as ally.

From 781 (Pallars, Ribagorça) to 806 (Pamplona under Frankish influence), taking the County of Toulouse for a power base, Charlemagne managed to assert Frankish authority on the Pyrenees by establishing vassal counties that were to make up the Marca Hispanica and provide the necessary springboard to attack the Hispanic Muslims (expedition led by William Count of Toulouse and Louis the Pious to capture Barcelona in 801), in a way that Charlemagne had succeeded in expanding the Carolingian rule all around the Pyrenees by 812, although events in the Duchy of Vasconia (rebellion in Pamplona, count overthrown in Aragon, duke Seguin of Bordeaux deposed, uprising of the Basque lords, etc.) were to prove it ephemeral on his death.

Roncesvalles campaign

According to the Muslim historian Ibn al-Athir, the Diet of Paderborn had received the representatives of the Muslim rulers of Saragossa, Girona, Barcelona, and Huesca. Their masters had been cornered in the Iberian peninsula by Abd ar-Rahman I, the Umayyad emir of Cordova. These Moorish or "Saracen" rulers offered their homage to the great king of the Franks in return for military support. Seeing an opportunity to extend Christendom and his own power and believing the Saxons to be a fully conquered nation, Charlemagne agreed to go to Spain.

In 778, he led the Neustrian army across the Western Pyrenees, while the Austrasians, Lombards, and Burgundians passed over the Eastern Pyrenees. The armies met at Saragossa and Charlemagne received the homage of the Muslim rulers, Sulayman al-Arabi and Kasmin ibn Yusuf, but the city did not fall for him. Indeed, Charlemagne was facing the toughest battle of his career where the Muslims had the upper hand and forced him to retreat. He decided to go home, since he could not trust the Basques, whom he had subdued by conquering Pamplona. He turned to leave Iberia, but as he was passing through the Pass of Roncesvalles one of the most famous events of his long reign occurred. The Basques fell on his rearguard and baggage train, utterly destroying it. The Battle of Roncevaux Pass, less a battle than a mere skirmish, left many famous dead: among which were the seneschal Eggihard, the count of the palace Anselm, and the warden of the Breton March, Roland, inspiring the subsequent creation of the Song of Roland (La Chanson de Roland).

Wars with the Moors

The conquest of Italy brought Charlemagne in contact with the Saracens who, at the time, controlled the Mediterranean. Pippin, his son, was much occupied with Saracens in Italy. Charlemagne conquered Corsica and Sardinia at an unknown date and in 799 the Balearic Islands. The islands were often attacked by Saracen pirates, but the counts of Genoa and Tuscany (Boniface) kept them at bay with large fleets until the end of Charlemagne's reign. Charlemagne even had contact with the caliphal court in Baghdad. In 797 (or possibly 801), the caliph of Baghdad, Harun al-Rashid, presented Charlemagne with an Asian elephant named Abul-Abbas and a clock.[33]

In Hispania, the struggle against the Moors continued unabated throughout the latter half of his reign. His son Louis was in charge of the Spanish border. In 785, his men captured Gerona permanently and extended Frankish control into the Catalan littoral for the duration of Charlemagne's reign (and much longer, it remained nominally Frankish until the Treaty of Corbeil in 1258). The Muslim chiefs in the northeast of Islamic Spain were constantly revolting against Cordovan authority, and they often turned to the Franks for help. The Frankish border was slowly extended until 795, when Gerona, Cardona, Ausona, and Urgel were united into the new Spanish March, within the old duchy of Septimania.

In 797 Barcelona, the greatest city of the region, fell to the Franks when Zeid, its governor, rebelled against Cordova and, failing, handed it to them. The Umayyad authority recaptured it in 799. However, Louis of Aquitaine marched the entire army of his kingdom over the Pyrenees and besieged it for two years, wintering there from 800 to 801, when it capitulated. The Franks continued to press forward against the emir. They took Tarragona in 809 and Tortosa in 811. The last conquest brought them to the mouth of the Ebro and gave them raiding access to Valencia, prompting the Emir al-Hakam I to recognize their conquests in 812.

Eastern campaigns

Saxon Wars

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2010) |

Charlemagne was engaged in almost constant battle throughout his reign,[34] often at the head of his elite scara bodyguard squadrons, with his legendary sword Joyeuse in hand. In the Saxon Wars, spanning thirty years and eighteen battles, he conquered Saxonia and proceeded to convert the conquered to Christianity.

The Germanic Saxons were divided into four subgroups in four regions. Nearest to Austrasia was Westphalia and furthest away was Eastphalia. In between these two kingdoms was that of Engria and north of these three, at the base of the Jutland peninsula, was Nordalbingia.

In his first campaign, Charlemagne forced the Engrians in 773 to submit and cut down an Irminsul pillar near Paderborn.[35] The campaign was cut short by his first expedition to Italy. He returned in 775, marching through Westphalia and conquering the Saxon fort of Sigiburg. He then crossed Engria, where he defeated the Saxons again. Finally, in Eastphalia, he defeated a Saxon force, and its leader Hessi converted to Christianity. Charlemagne returned through Westphalia, leaving encampments at Sigiburg and Eresburg, which had been important Saxon bastions. All of Saxony but Nordalbingia was under his control, but Saxon resistance had not ended.

Following his campaign in Italy to subjugate the dukes of Friuli and Spoleto, Charlemagne returned very rapidly to Saxony in 776, where a rebellion had destroyed his fortress at Eresburg. The Saxons were once again brought to heel, but their main leader, Widukind, managed to escape to Denmark, home of his wife. Charlemagne built a new camp at Karlstadt. In 777, he called a national diet at Paderborn to integrate Saxony fully into the Frankish kingdom. Many Saxons were baptised as Christians.

In the summer of 779, he again invaded Saxony and reconquered Eastphalia, Engria, and Westphalia. At a diet near Lippe, he divided the land into missionary districts and himself assisted in several mass baptisms (780). He then returned to Italy and, for the first time, there was no immediate Saxon revolt. Saxony was peaceful from 780 to 782.

He returned to Saxony in 782 and instituted a code of law and appointed counts, both Saxon and Frank. The laws were draconian on religious issues; for example, the Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae prescribed death to Saxon pagans who refused to convert to Christianity. This revived a renewal of the old conflict. That year, in autumn, Widukind returned and led a new revolt. In response, at Verden in Lower Saxony, Charlemagne is recorded as having ordered the execution of 4,500 Saxon prisoners, known as the Massacre of Verden ("Verdener Blutgericht"). The killings triggered three years of renewed bloody warfare (783–785). During this war the Frisians were also finally subdued and a large part of their fleet was burned. The war ended with Widukind accepting baptism.

Thereafter, the Saxons maintained the peace for seven years, but in 792 the Westphalians again rose against their conquerors. The Eastphalians and Nordalbingians joined them in 793, but the insurrection did not catch on and was put down by 794. An Engrian rebellion followed in 796, but the presence of Charlemagne, Christian Saxons and Slavs quickly crushed it. The last insurrection of the independent-minded people occurred in 804, more than thirty years after Charlemagne's first campaign against them. This time, the most restive of them, the Nordalbingians, found themselves effectively disempowered from rebellion for the time being. According to Einhard:

The war that had lasted so many years was at length ended by their acceding to the terms offered by the King; which were renunciation of their national religious customs and the worship of devils, acceptance of the sacraments of the Christian faith and religion, and union with the Franks to form one people.

Submission of Bavaria

In 789, Charlemagne turned his attention to Bavaria. He claimed Tassilo was an unfit ruler, due to his oath-breaking. The charges were exaggerated, but Tassilo was deposed anyway and put in the monastery of Jumièges. In 794, he was made to renounce any claim to Bavaria for himself and his family (the Agilolfings) at the synod of Frankfurt. Bavaria was subdivided into Frankish counties, as had been done with Saxony.

Avar campaigns

In 788, the Avars, a pagan Asian horde that had settled down in what is today Hungary (Einhard called them Huns), invaded Friuli and Bavaria. Charlemagne was preoccupied with other matters until 790, when he marched down the Danube and ravaged Avar territory to the Győr. A Lombard army under Pippin then marched into the Drava valley and ravaged Pannonia. The campaigns would have continued if the Saxons had not revolted again in 792, breaking seven years of peace.

For the next two years, Charlemagne was occupied, along with the Slavs, against the Saxons. Pippin and Duke Eric of Friuli continued, however, to assault the Avars' ring-shaped strongholds. The great Ring of the Avars, their capital fortress, was taken twice. The booty was sent to Charlemagne at his capital, Aachen, and redistributed to all his followers and even to foreign rulers, including King Offa of Mercia. Soon the Avar tuduns had thrown in the towel and traveled to Aachen to subject themselves to Charlemagne as vassals and Christians. Charlemagne accepted their surrender and sent one native chief, baptised Abraham, back to Avaria with the ancient title of khagan. Abraham kept his people in line, but in 800, the Bulgarians under Khan Krum also attacked the remains of Avar state.

In 803 Charlemagne sent a huge Bavarian army into Pannonia, defeating and bringing an end to the Avar confederation.[36] In November of the same year, Charlemagne went to Regensburg where the Avar leaders acknowledged him as their own ruler.[36] In 805 the Avar khagan, who had already been baptised, went to Aachen to ask permission to settle with his people south-eastward from Vienna.[36] The Transdanubian territories became integral parts of the Frankish realm, which was abolished by the Magyars in 899-900.

Northeast Slav expeditions

In 789, in recognition of his new pagan neighbours, the Slavs, Charlemagne marched an Austrasian-Saxon army across the Elbe into Obotrite territory. The Slavs immediately submitted, led by their leader Witzin. Charlemagne then accepted the surrender of the Wiltzes under Dragovit and demanded many hostages. Charlemagne also demanded the permission to send missionaries into this pagan region unmolested. The army marched to the Baltic before turning around and marching to the Rhine, winning much booty with no harassment. The tributary Slavs became loyal allies. In 795, when the Saxons broke the peace, the Abotrites and Wiltzes rose in arms with their new master against the Saxons. Witzin died in battle and Charlemagne avenged him by harrying the Eastphalians on the Elbe. Thrasuco, his successor, led his men to conquest over the Nordalbingians and handed their leaders over to Charlemagne, who greatly honoured him. The Abotrites remained loyal until Charles' death and fought later against the Danes.

Southeast Slav expeditions

When Charlemagne incorporated much of Central Europe, he brought the Frankish state face to face with the Avars and Slavs in the southeast.[37] The most southeast Frankish neighbors were Croats, who settled in Pannonian Croatia and Dalmatian Croatia. While fighting the Avars, the Franks had called for their support.[38] During the 790s, when Charlemagne campaigned against the Avars, he won a major victory in 796.[39] Pannonian Croatian duke Vojnomir of Pannonian Croatia aided Charlemagne, and the Franks made themselves overlords over the Croatians of northern Dalmatia, Slavonia, and Pannonia.[39]

The Frankish commander Eric of Friuli wanted to extend his dominion by conquering Littoral Croatian Duchy. During that time, Dalmatian Croatia was ruled by duke Višeslav of Croatia, who was one of the first known Croatian dukes.[40] In the Battle of Trsat, the forces of Eric fled their positions and were totally routed by the forces of Višeslav.[40] Eric himself was among the killed, and his death and defeat proved a great blow for the Carolingian Empire.[37][40][41]

Charlemagne also directed his attention to the Slavs to the west of the Avar khaganate: the Carantanians and Carniolans. These people were subdued by the Lombards and Bavarii, were made tributaries, but were never fully incorporated into the Frankish state.

Imperium

Coronation

In 799, Pope Leo III had been mistreated by the Romans, who tried to put out his eyes and tear out his tongue. Leo escaped and fled to Charlemagne at Paderborn, asking him to intervene in Rome and restore him. Charlemagne, advised by Alcuin of York, agreed to travel to Rome, doing so in November 800 and holding a council on 1 December. On 23 December Leo swore an oath of innocence. At Mass, on Christmas Day (25 December), when Charlemagne knelt at the altar to pray, the Pope crowned him Imperator Romanorum ("Emperor of the Romans") in Saint Peter's Basilica. In so doing, the Pope was effectively nullifying the legitimacy of Empress Irene of Constantinople:

- "When Odoacer compelled the abdication of Romulus Augustulus, he did not abolish the Western Empire as a separate power, but cause it to be reunited with or sink into the Eastern, so that from that time there was a single undivided Roman Empire ... [Pope Leo III and Charlemagne], like their predecessors, held the Roman Empire to be one and indivisible, and proposed by the coronation of [Charlemagne] not to proclaim a severance of the East and West ... they were not revolting against a reigning sovereign, but legitimately filling up the place of the deposed Constantine VI ... [Charlemagne] was held to be the legitimate successor, not of Romulus Augustulus, but of Constantine VI ..."[42]

Charlemagne's coronation as Emperor, though intended to represent the continuation of the unbroken line of Emperors from Augustus to Constantine VI, had the effect of setting up two separate (and often opposing) Empires and two separate claims to imperial authority. For centuries to come, the Emperors of both West and East would make competing claims of sovereignty over the whole.

Einhard says that Charlemagne was ignorant of the Pope's intent and did not want any such coronation:

[H]e at first had such an aversion that he declared that he would not have set foot in the Church the day that they [the imperial titles] were conferred, although it was a great feast-day, if he could have foreseen the design of the Pope.

A number of modern scholars, however,[43] suggest that Charlemagne was indeed aware of the coronation; certainly he cannot have missed the bejeweled crown waiting on the altar when he came to pray.

In any event, Charlemagne used these circumstances to claim that he was the renewer of the Roman Empire, which had apparently fallen into degradation under the Byzantines. In his official charters, Charles preferred the style Karolus serenissimus Augustus a Deo coronatus magnus pacificus imperator Romanum gubernans imperium[44] ("Charles, most serene Augustus crowned by God, the great, peaceful emperor ruling the Roman empire") to the more direct Imperator Romanorum ("Emperor of the Romans").

Imperial Diplomacy

The iconoclasm of the Byzantine Isaurian Dynasty was endorsed by the Franks.[45] The Second Council of Nicaea reintroduced the veneration of icons under Empress Irene. The council was not recognized by Charlemagne since no Frankish emissaries had been invited, even though Charlemagne ruled more than three provinces of the old Roman empire and was considered equal in rank to the Byzantine emperor. And while the Pope supported the reintroduction of the iconic veneration, he politically digressed from Byzantium.[45] He certainly desired to increase the influence of the papacy, to honour his saviour Charlemagne, and to solve the constitutional issues then most troubling to European jurists in an era when Rome was not in the hands of an emperor. Thus, Charlemagne's assumption of the imperial title was not a usurpation in the eyes of the Franks or Italians. It was, however, seen as such in Byzantium, where it was protested by Irene and her successor Nicephorus I — neither of whom had any great effect in enforcing their protests.

The Byzantines, however, still held several territories in Italy: Venice (what was left of the Exarchate of Ravenna), Reggio (in Calabria), Brindisi (in Apulia), and Naples (the Ducatus Neapolitanus). These regions remained outside of Frankish hands until 804, when the Venetians, torn by infighting, transferred their allegiance to the Iron Crown of Pippin, Charles' son. The Pax Nicephori ended. Nicephorus ravaged the coasts with a fleet, initiating the only instance of war between the Byzantines and the Franks. The conflict lasted until 810, when the pro-Byzantine party in Venice gave their city back to the Byzantine Emperor, and the two emperors of Europe made peace: Charlemagne received the Istrian peninsula and in 812 the emperor Michael I Rhangabes recognised his status as Emperor,[46] although not necessarily as "Emperor of the Romans".[47]

Danish attacks

After the conquest of Nordalbingia, the Frankish frontier was brought into contact with Scandinavia. The pagan Danes, "a race almost unknown to his ancestors, but destined to be only too well known to his sons" as Charles Oman described them, inhabiting the Jutland peninsula, had heard many stories from Widukind and his allies who had taken refuge with them about the dangers of the Franks and the fury which their Christian king could direct against pagan neighbours.

In 808, the king of the Danes, Godfred, built the vast Danevirke across the isthmus of Schleswig. This defence, last employed in the Danish-Prussian War of 1864, was at its beginning a 30 km (19 mi) long earthenwork rampart. The Danevirke protected Danish land and gave Godfred the opportunity to harass Frisia and Flanders with pirate raids. He also subdued the Frank-allied Wiltzes and fought the Abotrites.

Godfred invaded Frisia, joked of visiting Aachen, but was murdered before he could do any more, either by a Frankish assassin or by one of his own men. Godfred was succeeded by his nephew Hemming, who concluded the Treaty of Heiligen with Charlemagne in late 811.

Death

In 813, Charlemagne called Louis the Pious, king of Aquitaine, his only surviving legitimate son, to his court. There Charlemagne crowned his son with his own hands as co-emperor and sent him back to Aquitaine. He then spent the autumn hunting before returning to Aachen on 1 November. In January, he fell ill with pleurisy.[48] In deep depression (mostly because many of his plans were not yet realized), he took to his bed on 21 January and as Einhard tells it:

He died January twenty-eighth, the seventh day from the time that he took to his bed, at nine o'clock in the morning, after partaking of the Holy Communion, in the seventy-second year of his age and the forty-seventh of his reign.

He was buried the same day as his death, in Aachen Cathedral, although the cold weather and the nature of his illness made such a hurried burial unnecessary. The earliest surviving planctus, the Planctus de obitu Karoli, was composed by a monk of Bobbio, which he had patronised.[49] A later story, told by Otho of Lomello, Count of the Palace at Aachen in the time of Otto III, would claim that he and Emperor Otto had discovered Charlemagne's tomb: the emperor, they claimed, was seated upon a throne, wearing a crown and holding a sceptre, his flesh almost entirely incorrupt. In 1165, Frederick I re-opened the tomb again and placed the emperor in a sarcophagus beneath the floor of the cathedral.[50] In 1215 Frederick II re-interred him in a casket made of gold and silver.

Charlemagne's death greatly affected many of his subjects, particularly those of the literary clique who had surrounded him at Aachen. An anonymous monk of Bobbio lamented:[51]

From the lands where the sun rises to western shores, people are crying and wailing ... the Franks, the Romans, all Christians, are stung with mourning and great worry ... the young and old, glorious nobles, all lament the loss of their Caesar ... the world laments the death of Charles ... O Christ, you who govern the heavenly host, grant a peaceful place to Charles in your kingdom. Alas for miserable me.

He was succeeded by his surviving son, Louis, who had been crowned the previous year. His empire lasted only another generation in its entirety; its division, according to custom, between Louis's own sons after their father's death laid the foundation for the modern state of Germany.[52]

Administration

As an administrator, Charlemagne stands out for his many reforms: monetary, governmental, military, cultural, and ecclesiastical. He is the main protagonist of the "Carolingian Renaissance."

Military

It has long been held that the dominance of Charlemagne's military was based on a "cavalry revolution" led by Charles Martel in 730s. However, the stirrup, which made the "shock cavalry" lance charge possible, was not introduced to the Frankish kingdom until the late eighth century.[53] Instead, Charlemagne's success rested primarily on novel siege technologies and excellent logistics.[54]

However, large numbers of horses were used by the Frankish military during the age of Charlemagne. This was because horses provided a quick, long-distance method of transporting troops, which was critical to building and maintaining such a large empire.[53]

Economic and monetary reforms

Charlemagne had an important role in determining the immediate economic future of Europe. Pursuing his father's reforms, Charlemagne abolished the monetary system based on the gold [sou] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), and he and the Anglo-Saxon King Offa of Mercia took up the system set in place by Pippin. There were strong pragmatic reasons for this abandonment of a gold standard, notably a shortage of gold itself.

The gold shortage was a direct consequence of the conclusion of peace with Byzantium, which resulted in ceding Venice and Sicily to the East and losing their trade routes to Africa. The resulting standardisation economically harmonized and unified the complex array of currencies which had been in use at the commencement of his reign, thus simplifying trade and commerce.

Charlemagne established a new standard, the [livre carolinienne] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (from the Latin [[[Ancient Roman units of measurement|libra]]] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), the modern pound), which was based upon a pound of silver—a unit of both money and weight—which was worth 20 sous (from the Latin [solidus] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [which was primarily an accounting device and never actually minted], the modern shilling) or 240 [deniers] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (from the Latin [denarius] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), the modern penny). During this period, the [livre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and the [sou] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) were counting units; only the [denier] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) was a coin of the realm.

Charlemagne instituted principles for accounting practice by means of the Capitulare de villis of 802, which laid down strict rules for the way in which incomes and expenses were to be recorded.

Lending money for interest was proscribed in 814, when Charlemagne introduced the Capitulary for the Jews, a prohibition on Jews engaging in money-lending due to religious beliefs of Christians, in essence banning it across the board. In addition to this macro-oriented reform of the economy, Charlemagne also performed a significant number of microeconomic reforms, such as direct control of prices and levies on certain goods and commodities.

Charlemagne applied this system to much of the European continent, and Offa's standard was voluntarily adopted by much of England. After Charlemagne's death, continental coinage degraded, and most of Europe resorted to using the continued high-quality English coin until about 1100.

Education reforms

A part of Charlemagne's success as warrior and administrator can be traced to his admiration for learning. His reign and the era it ushered in are often referred to as the Carolingian Renaissance because of the flowering of scholarship, literature, art, and architecture which characterize it. Charlemagne, brought into contact with the culture and learning of other countries (especially Visigothic Spain, Anglo-Saxon England, and Lombard Italy) due to his vast conquests, greatly increased the provision of monastic schools and scriptoria (centres for book-copying) in Francia.

Most of the presently surviving works of classical Latin were copied and preserved by Carolingian scholars. Indeed, the earliest manuscripts available for many ancient texts are Carolingian. It is almost certain that a text which survived to the Carolingian age survives still.

The pan-European nature of Charlemagne's influence is indicated by the origins of many of the men who worked for him: Alcuin, an Anglo-Saxon from York; Theodulf, a Visigoth, probably from Septimania; Paul the Deacon, Lombard; Peter of Pisa and Paulinus of Aquileia, Italians; and Angilbert, Angilram, Einhard, and Waldo of Reichenau, Franks.

Charlemagne took a serious interest in scholarship, promoting the liberal arts at the court, ordering that his children and grandchildren be well-educated, and even studying himself (in a time when even leaders who promoted education did not take time to learn themselves) under the tutelage of Peter of Pisa, from whom he learned grammar; Alcuin, with whom he studied rhetoric, dialectic (logic), and astronomy (he was particularly interested in the movements of the stars); and Einhard, who assisted him in his studies of arithmetic.[55]

His great scholarly failure, as Einhard relates, was his inability to write: when in his old age he began attempts to learn—practicing the formation of letters in his bed during his free time on books and wax tablets he hid under his pillow—"his effort came too late in life and achieved little success", and his ability to read – which Einhard is silent about, and which no contemporary source supports—has also been called into question.[55]

In 800, Charlemagne enlarged the hostel at the Muristan in Jerusalem and added a library to it. He certainly had not been personally in Jerusalem.[56][57]

Church reforms

Writing reforms

During Charles' reign, the Roman half uncial script and its cursive version, which had given rise to various continental minuscule scripts, were combined with features from the insular scripts that were being used in Irish and English monasteries. Carolingian minuscule was created partly under the patronage of Charlemagne. Alcuin of York, who ran the palace school and scriptorium at Aachen, was probably a chief influence in this.

The revolutionary character of the Carolingian reform, however, can be over-emphasised; efforts at taming the crabbed Merovingian and Germanic hands had been underway before Alcuin arrived at Aachen. The new minuscule was disseminated first from Aachen and later from the influential scriptorium at Tours, where Alcuin retired as an abbot.

Political reforms

Charlemagne engaged in many reforms of Frankish governance, but he continued also in many traditional practices, such as the division of the kingdom among sons.[citation needed]

Organization

The Carolingian king exercised the bannum, the right to rule and command. He had supreme jurisdiction in judicial matters, made legislation, led the army, and protected both the Church and the poor. His administration was an attempt to organize the kingdom, church, and nobility around him. However, the effort was heavily dependent upon the efficiency, loyalty, and support of his subjects.[citation needed]

Imperial coronation

Historians have debated for centuries whether Charlemagne was aware of the Pope's intent to crown him Emperor prior to the coronation (Charlemagne declared that he would not have entered Saint Peter's had he known), but that debate has often obscured the more significant question of why the Pope granted the title and why Charlemagne chose to accept it once he did.[58]

Roger Collins points out "[t]hat the motivation behind the acceptance of the imperial title was a romantic and antiquarian interest in reviving the Roman empire is highly unlikely."[59] For one thing, such romance would not have appealed either to Franks or Roman Catholics at the turn of the ninth century, both of whom viewed the Classical heritage of the Roman Empire with distrust. The Franks took pride in having "fought against and thrown from their shoulders the heavy yoke of the Romans" and "from the knowledge gained in baptism, clothed in gold and precious stones the bodies of the holy martyrs whom the Romans had killed by fire, by the sword and by wild animals", as Pippin III described it in a law of 763 or 764.[60]

Furthermore, the new title—carrying with it the risk that the new emperor would "make drastic changes to the traditional styles and procedures of government" or "concentrate his attentions on Italy or on Mediterranean concerns more generally"—risked alienating the Frankish leadership.[61]

For both the Pope and Charlemagne, the Roman Empire remained a significant power in European politics at this time, and continued to hold a substantial portion of Italy, with borders not very far south of the city of Rome itself—this is the empire historiography has labelled the Byzantine Empire, for its capital was Constantinople (ancient Byzantium) and its people and rulers were Greek; it was a thoroughly Hellenic state. Indeed, Charlemagne was usurping the prerogatives of the Roman Emperor in Constantinople simply by sitting in judgement over the Pope in the first place:

By whom, however, could he [the Pope] be tried? Who, in other words, was qualified to pass judgement on the Vicar of Christ? In normal circumstances the only conceivable answer to that question would have been the Emperor at Constantinople; but the imperial throne was at this moment occupied by Irene. That the Empress was notorious for having blinded and murdered her own son was, in the minds of both Leo and Charles, almost immaterial: it was enough that she was a woman. The female sex was known to be incapable of governing, and by the old Salic tradition was debarred from doing so. As far as Western Europe was concerned, the Throne of the Emperors was vacant: Irene's claim to it was merely an additional proof, if any were needed, of the degradation into which the so-called Roman Empire had fallen.

— John Julius Norwich, Byzantium: The Early Centuries, pg. 378

For the Pope, then, there was "no living Emperor at the that time"[62] though Henri Pirenne[63] disputes this saying that the coronation "was not in any sense explained by the fact that at this moment a woman was reigning in Constantinople." Nonetheless, the Pope took the extraordinary step of creating one. The papacy had since 727 been in conflict with Irene's predecessors in Constantinople over a number of issues, chiefly the continued Byzantine adherence to the doctrine of iconoclasm, the destruction of Christian images; while from 750, the secular power of the Byzantine Empire in central Italy had been nullified.

By bestowing the Imperial crown upon Charlemagne, the Pope arrogated to himself "the right to appoint ... the Emperor of the Romans, ... establishing the imperial crown as his own personal gift but simultaneously granting himself implicit superiority over the Emperor whom he had created." And "because the Byzantines had proved so unsatisfactory from every point of view—political, military and doctrinal—he would select a westerner: the one man who by his wisdom and statesmanship and the vastness of his dominions ... stood out head and shoulders above his contemporaries."

With Charlemagne's coronation, therefore, "the Roman Empire remained, so far as either of them [Charlemagne and Leo] were concerned, one and indivisible, with Charles as its Emperor", though there can have been "little doubt that the coronation, with all that it implied, would be furiously contested in Constantinople."[64]

How realistic either Charlemagne or the Pope felt it to be that the people of Constantinople would ever accept the King of the Franks as their Emperor, we cannot know; Alcuin speaks hopefully in his letters of an Imperium Christianum ("Christian Empire"), wherein, "just as the inhabitants of the [Roman Empire] had been united by a common Roman citizenship", presumably this new empire would be united by a common Christian faith,[60] certainly this is the view of Pirenne when he says "Charles was the Emperor of the ecclesia as the Pope conceived it, of the Roman Church, regarded as the universal Church".[65] The Imperium Christianum was further supported at a number of synods all across the Europe by Paulinus of Aquileia.[66]

What is known, from the Byzantine chronicler Theophanes,[67] is that Charlemagne's reaction to his coronation was to take the initial steps toward securing the Constantinopolitan throne by sending envoys of marriage to Irene, and that Irene reacted somewhat favorably to them.

It is important to distinguish between the universalist and localist conceptions of the empire, which have been the source of considerable controversy among historians. According to the former, the empire was a universal monarchy, a "commonwealth of the whole world, whose sublime unity transcended every minor distinction"; and the emperor "was entitled to the obedience of Christendom." According to the latter, the emperor had no ambition for universal dominion; his policy was limited in the same way as that of every other ruler, and when he made more far-reaching claims his object was normally to ward off the attacks either of the pope or of the Byzantine emperor. According to this view, also, the origin of the empire is to be explained by specific local circumstances rather than by far-flung theories.[68]

According to Werner Ohnsorge, for a long time it had been the custom of Byzantium to designate the German princes as spiritual "sons" of the Byzantines. What might have been acceptable in the fifth century, to the pride of the Franks in the eighth century was provoking and insulting. Charles came to the realization that the great Roman emperor, who claimed to be the head of the world hierarchy of states, in reality was no greater than Charles himself, a king as other kings, since beginning in 629 he had entitled himself "Basileus" (translated literally as "king"). Ohnsorge finds it significant that the chief wax seal of Charles, which bore only the inscription: "Christe, protege Carolum regem Francorum [Christ, protect Charles, king of the Franks], was used from 772 to 813, even during the imperial period and was not replaced by a special imperial seal; indicating that Charles felt himself to be king of the Franks and wished only for the greatness of his Frankish people. Finally, Ohnsorge points out that in the spring of 813 at Aachen Charles crowned his youngest, only surviving son, Louis, as emperor without recourse to Rome and only with the acclamation of his Franks, also the form in which this acclamation was offered was no longer Roman, but Frankish-Christian; thus demonstrating both independence from Rome, and a Frankish understanding of empire different from Rome's.[69]

The title of emperor remained in his family for years to come, however, as brothers fought over who had the supremacy in the Frankish state. The papacy itself never forgot the title nor abandoned the right to bestow it. When the family of Charles ceased to produce worthy heirs, the pope gladly crowned whichever Italian magnate could best protect him from his local enemies.

This devolution led, as could have been expected, to the dormancy of the title for almost forty years (924–962). Finally, in 962, in a radically different Europe from Charlemagne's, a new Roman Emperor was crowned in Rome by a grateful pope. This emperor, Otto the Great, brought the title into the hands of the kings of Germany for almost a millennium, for it was to become the Holy Roman Empire, a true imperial successor to that of Charles, if not Augustus.

Divisio regnorum

In 806, Charlemagne first made provision for the traditional division of the empire on his death. For Charles the Younger he designated Austrasia and Neustria, Saxony, Burgundy, and Thuringia. To Pippin he gave Italy, Bavaria, and Swabia. Louis received Aquitaine, the Spanish March, and Provence. There was no mention of the imperial title however, which has led to the suggestion that, at that particular time, Charlemagne regarded the title as an honorary achievement which held no hereditary significance.

This division might have worked, but it was never to be tested. Pippin died in 810 and Charles in 811. Charlemagne then reconsidered the matter, and in 813, crowned his youngest son, Louis, co-emperor and co-King of the Franks, granting him a half-share of the empire and the rest upon Charlemagne's own death. The only part of the Empire which Louis was not promised was Italy, which Charlemagne specifically bestowed upon Pippin's illegitimate son Bernard.

Personality

Language

By Charlemagne's time the French vernacular had already diverged significantly from Latin. This is evidenced by one of the regulations of the Council of Tours (813), which required that the parish priests preach either in the "rusticam Romanam linguam" (Romance) or "Theotiscam" (the Germanic vernacular) rather than in Latin. The goal of this rule was to make the sermons comprehensible to the common people, who must therefore have been either Romance speakers or Germanic speakers.[70] Charlemagne himself probably spoke a Rhenish Franconian dialect of Old High German.[71]

Apart from his native language he also spoke Latin "as well as his native tongue" and understood a bit of Greek, according to his biographer Einhard (Grecam vero melius intellegere quam pronuntiare poterat, "he could understand Greek better than he could speak it").[72] Einhard also writes that Charlemagne started a "grammar of his native language" and "gave the months names in his own tongue".[73] The names are: Wintarmanoth, Hornung, Lentzinmanoth, Ostarmanoth, Winnemanoth, Brachmanoth, Heuvimanoth, Aranmanoth, Witumanoth, Windumemanoth, Herbistmanoth, Heilagmanoth. All of his daughters received Old High German names.[citation needed]

The largely fictional account of Charlemagne's Iberian campaigns by Pseudo-Turpin, written some three centuries after his death, gave rise to the legend that the king also spoke Arabic.[74]

Appearance

Charlemagne's personal appearance is known from a good description by a personal associate, Einhard, author after his death of the biography Vita Karoli Magni. Einhard tells in his twenty-second chapter:[75]

"He was heavily built, sturdy, and of considerable stature, although not exceptionally so, since his height was seven times the length of his own foot. He had a round head, large and lively eyes, a slightly larger nose than usual, white but still attractive hair, a bright and cheerful expression, a short and fat neck, and he enjoyed good health, except for the fevers that affected him in the last few years of his life. Toward the end, he dragged one leg. Even then, he stubbornly did what he wanted and refused to listen to doctors, indeed he detested them, because they wanted to persuade him to stop eating roast meat, as was his wont, and to be content with boiled meat."

The physical portrait provided by Einhard is confirmed by contemporary depictions of the emperor, such as coins and his 8-inch (20 cm) bronze statue kept in the Louvre. In 1861, Charlemagne's tomb was opened by scientists who reconstructed his skeleton and estimated it to be measured 74.9 in (190 cm).[76] An estimate of his height from an X-ray and CT Scan of his tibia performed in 2010 is 1.84 m (72 in). This puts him in the 99th percentile of tall people of his period, given that average male height of his time was 1.69 m (67 in). The width of the bone suggested he was gracile but not robust in body build.[77]

Dress

Charlemagne wore the traditional costume of the Frankish people, described by Einhard thus:[78]

"He used to wear the national, that is to say, the Frank, dress-next his skin a linen shirt and linen breeches, and above these a tunic fringed with silk; while hose fastened by bands covered his lower limbs, and shoes his feet, and he protected his shoulders and chest in winter by a close-fitting coat of otter or marten skins."

He wore a blue cloak and always carried a sword with him. The typical sword was of a golden or silver hilt. He wore fancy jewelled swords to banquets or ambassadorial receptions. Nevertheless:[78]

"He despised foreign costumes, however handsome, and never allowed himself to be robed in them, except twice in Rome, when he donned the Roman tunic, chlamys, and shoes; the first time at the request of Pope Hadrian, the second to gratify Leo, Hadrian's successor."

He could rise to the occasion when necessary. On great feast days, he wore embroidery and jewels on his clothing and shoes. He had a golden buckle for his cloak on such occasions and would appear with his great diadem, but he despised such apparel, according to Einhard, and usually dressed like the common people.[78]

Family

Marriages and heirs

Charlemagne had eighteen children over the course of his life with eight of his ten known wives or concubines.[79] Nonetheless, he only had four legitimate grandsons, the four sons of his fourth son, Louis. In addition, he had a grandson (Bernard of Italy, the only son of his third son, Pippin of Italy), who was born illegitimate but included in the line of inheritance. So, despite eighteen children, the claimants to his inheritance were few.

| Start date | Marriages and heirs | Concubinages and illegitimate children |

|---|---|---|

| ca.768 | His first relationship was with Himiltrude. The nature of this relationship is variously described as concubinage, a legal marriage, or a Friedelehe.[80] (Charlemagne put her aside when he married Desiderata.) The union with Himiltrude produced two children:

|

|

| ca. 770 | After her, his first wife was Desiderata, daughter of Desiderius, king of the Lombards; married in 770, annulled in 771. | |

| ca. 771 | His second wife was Hildegard of Vinzgouw (757 or 758–783), married 771, died 783. By her he had nine children:

|

|

| ca. 773 | His first known concubine was Gersuinda. By her he had:

| |

| ca. 774 | His second known concubine was Madelgard. By her he had:

| |

| ca. 784 | His third wife was Fastrada, married 784, died 794. By her he had:

|

|