Millennium Development Goals: Difference between revisions

Cwsturgeon15 (talk | contribs) I added a paragraph under "Libraries and the Millennium Development Goals" that discusses LIS education in Sub-Saharan Africa. |

Sagarkrbihar (talk | contribs) No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Among the non-governmental organizations assisting were the United Nations Millennium Campaign, the Millennium Promise Alliance, Inc., the Global Poverty Project, the [[Micah Challenge UK|Micah Challenge]], The Youth in Action EU Programme, "Cartoons in Action" video project and the 8 Visions of Hope global art project. |

Among the non-governmental organizations assisting were the United Nations Millennium Campaign, the Millennium Promise Alliance, Inc., the Global Poverty Project, the [[Micah Challenge UK|Micah Challenge]], The Youth in Action EU Programme, "Cartoons in Action" video project and the 8 Visions of Hope global art project. |

||

Bhai log m to Apna assingment bana liya hu..tu v bana lo plzzz.. |

|||

bye love u ....Rohit Ranjan.. |

|||

{{toclimit|3}} |

{{toclimit|3}} |

||

Revision as of 19:50, 29 March 2015

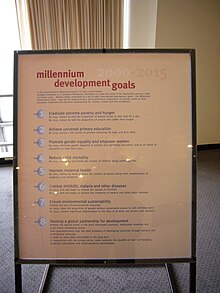

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) are eight international development goals that were established following the Millennium Summit of the United Nations in 2000, following the adoption of the United Nations Millennium Declaration. All 189 United Nations member states at the time (there are 193 currently), and at least 23 international organizations, committed to help achieve the following Millennium Development Goals by 2015:

- To eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- To achieve universal primary education

- To promote gender equality and empower women

- To reduce child mortality

- To improve maternal health

- To combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- To ensure environmental sustainability[1]

- To develop a global partnership for development[2]

Each goal has specific targets, and dates for achieving those targets. To accelerate progress, the G8 finance ministers agreed in June 2005 to provide enough funds to the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the African Development Bank (AfDB) to cancel $40 to $55 billion in debt owed by members of the heavily indebted poor countries (HIPC) to allow them to redirect resources to programs for improving health and education and for alleviating poverty.

Critics of the MDGs complained of a lack of analysis and justification behind the chosen objectives, and the difficulty or lack of measurements for some goals and uneven progress, among others. Although developed countries' aid for achieving the MDGs rose during the challenge period, more than half went for debt relief and much of the remainder going towards natural disaster relief and military aid, rather than further development.

As of 2013, progress towards the goals was uneven. Some countries achieved many goals, while others were not on track to realize any. A UN conference in September 2010 reviewed progress to date and concluded with the adoption of a global plan to achieve the eight goals by their target date. New commitments targeted women's and children's health, and new initiatives in the worldwide battle against poverty, hunger and disease.

Among the non-governmental organizations assisting were the United Nations Millennium Campaign, the Millennium Promise Alliance, Inc., the Global Poverty Project, the Micah Challenge, The Youth in Action EU Programme, "Cartoons in Action" video project and the 8 Visions of Hope global art project. Bhai log m to Apna assingment bana liya hu..tu v bana lo plzzz.. bye love u ....Rohit Ranjan..

Background

Millennium Summit

Preparations for the 2000 Millennium Summit launched with the report of the Secretary-General entitled, "We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the Twenty-First Century". Additional input was prepared by the Millennium Forum, which brought together representatives of over 1,000 non-governmental and civil society organizations from more than 100 countries. The Forum met in May to conclude a two-year consultation process covering issues such as poverty eradication, environmental protection, human rights and protection of the vulnerable.

MDGs derive from earlier development targets, where world leaders adopted the United Nations Millennium Declaration. The approval of the Millennium Declaration was the main outcome of the Millennium Summit.

The MDGs originated from the United Nations Millennium Declaration. The Declaration asserted that every individual has dignity; and hence, the right to freedom, equality, a basic standard of living that includes freedom from hunger and violence and encourages tolerance and solidarity. The MDGs set concrete targets and indicators for poverty reduction in order to achieve the rights set forth in the Declaration.[3]

Precursors

The Brahimi Report provided the basis of the goals in the area of peace and security.[citation needed]

The Millennium Summit Declaration was, however, only part of the origins of the MDGs. More ideas came from Adam Figueroa,[citation needed] Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. A series of UN‑led conferences in the 1990s focused on issues such as children, nutrition, human rights and women. The OECD criticized major donors for reducing their levels of Official Development Assistance (ODA). UN Secretary General Kofi Annan signed a report titled, We the Peoples: The Role of the United Nations in the 21st Century. The OECD had formed its International Development Goals (IDGs). The two efforts were combined for the World Bank's 2001 meeting to form the MDGs.[4]

Human capital, infrastructure and human rights

The MDG emphasized three areas: human capital, infrastructure and human rights (social, economic and political), with the intent of increasing living standards.[5] Human capital objectives include nutrition, healthcare (including child mortality, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria, and reproductive health) and education. Infrastructure objectives include access to safe drinking water, energy and modern information/communication technology; increased farm outputs using sustainable practices; transportation; and environment. Human rights objectives include empowering women, reducing violence, increasing political voice, ensuring equal access to public services and increasing security of property rights. The goals were intended to increase an individual’s human capabilities and "advance the means to a productive life". The MDGs emphasize that each nation's policies should be tailored to that country's needs; therefore most policy suggestions are general.

Partnership

MDGs emphasize the role of developed countries in aiding developing countries, as outlined in Goal Eight, which sets objectives and targets for developed countries to achieve a "global partnership for development" by supporting fair trade, debt relief, increasing aid, access to affordable essential medicines and encouraging technology transfer. Thus developing nations ostensibly became partners with developed nations in the struggle to reduce world poverty.

Goals

The MDGs were developed out of several commitments set forth in the Millennium Declaration, signed in September 2000. There are eight goals with 21 targets,[6] and a series of measurable health indicators and economic indicators for each target.[7][8]

Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Target 1A: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day[9]

- Poverty gap ratio [incidence x depth of poverty]

- Share of poorest quintile in national consumption

- Target 1B: Achieve Decent Employment for Women, Men, and Young People

- GDP Growth per Employed Person

- Employment Rate

- Proportion of employed population below $1.25 per day (PPP values)

- Proportion of family-based workers in employed population

- Target 1C: Halve, between 1990 and 2015, the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

- Prevalence of underweight children under five years of age

- Proportion of population below minimum level of dietary energy consumption[10]

Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education

- Target 2A: By 2015, all children can complete a full course of primary schooling, girls and boys

- Enrolment in primary education

- Completion of primary education[11]

Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women

- Target 3A: Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education preferably by 2005, and at all levels by 2015

- Ratios of girls to boys in primary, secondary and tertiary education

- Share of women in wage employment in the non-agricultural sector

- Proportion of seats held by women in national parliament[12]

Goal 4: Reduce child mortality rates

- Target 4A: Reduce by two-thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate

- Under-five mortality rate

- Infant (under 1) mortality rate

- Proportion of 1-year-old children immunized against measles[13]

Goal 5: Improve maternal health

- Target 5A: Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio

- Maternal mortality ratio

- Proportion of births attended by skilled health personnel

- Target 5B: Achieve, by 2015, universal access to reproductive health

- Contraceptive prevalence rate

- Adolescent birth rate

- Antenatal care coverage

- Unmet need for family planning[14]

Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases

- Target 6A: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS

- HIV prevalence among population aged 15–24 years

- Condom use at last high-risk sex

- Proportion of population aged 15–24 years with comprehensive correct knowledge of HIV/AIDS

- Target 6B: Achieve, by 2010, universal access to treatment for HIV/AIDS for all those who need it

- Proportion of population with advanced HIV infection with access to antiretroviral drugs

- Target 6C: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases

- Prevalence and death rates associated with malaria

- Proportion of children under 5 sleeping under insecticide-treated bednets

- Proportion of children under 5 with fever who are treated with appropriate anti-malarial drugs

- Incidence, prevalence and death rates associated with tuberculosis

- Proportion of tuberculosis cases detected and cured under DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment Short Course)[15]

2013 educational improvement

Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

- Target 7A: Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programs; reverse loss of environmental resources

- Target 7B: Reduce biodiversity loss, achieving, by 2010, a significant reduction in the rate of loss

- Proportion of land area covered by forest

- CO2 emissions, total, per capita and per $1 GDP (PPP)

- Consumption of ozone-depleting substances

- Proportion of fish stocks within safe biological limits

- Proportion of total water resources used

- Proportion of terrestrial and marine areas protected

- Proportion of species threatened with extinction

- Target 7C: Halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation (for more information see the entry on water supply)

- Proportion of population with sustainable access to an improved water source, urban and rural

- Proportion of urban population with access to improved sanitation

- Target 7D: By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum-dwellers

Goal 8: Develop a global partnership for development

- Target 8A: Develop further an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system

- Includes a commitment to good governance, development, and poverty reduction – both nationally and internationally

- Target 8B: Address the Special Needs of the Least Developed Countries (LDCs)

- Includes: tariff and quota free access for LDC exports; enhanced programme of debt relief for HIPC and cancellation of official bilateral debt; and more generous ODA (Official Development Assistance) for countries committed to poverty reduction

- Target 8C: Address the special needs of landlocked developing countries and small island developing States

- Through the Programme of Action for the Sustainable Development of Small Island Developing States and the outcome of the twenty-second special session of the General Assembly

- Target 8D: Deal comprehensively with the debt problems of developing countries through national and international measures in order to make debt sustainable in the long term

- Some of the indicators listed below are monitored separately for the least developed countries (LDCs), Africa, landlocked developing countries and small island developing States.

- Official development assistance (ODA):

- Net ODA, total and to LDCs, as percentage of OECD/DAC donors’ GNI

- Proportion of total sector-allocable ODA of OECD/DAC donors to basic social services (basic education, primary health care, nutrition, safe water and sanitation)

- Proportion of bilateral ODA of OECD/DAC donors that is untied

- ODA received in landlocked countries as proportion of their GNIs

- ODA received in small island developing States as proportion of their GNIs

- Market access:

- Proportion of total developed country imports (by value and excluding arms) from developing countries and from LDCs, admitted free of duty

- Average tariffs imposed by developed countries on agricultural products and textiles and clothing from developing countries

- Agricultural support estimate for OECD countries as percentage of their GDP

- Proportion of ODA provided to help build trade capacity

- Debt sustainability:

- Total number of countries that have reached their HIPC decision points and number that have reached their HIPC completion points (cumulative)

- Debt relief committed under HIPC initiative, US$

- Debt service as a percentage of exports of goods and services

- Target 8E: In co-operation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable, essential drugs in developing countries

- Proportion of population with access to affordable essential drugs on a sustainable basis

- Target 8F: In co-operation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications

- Telephone lines and cellular subscribers per 100 population

- Personal computers in use per 100 population

- Internet users per 100 Population[17]

Gaps

General

General criticisms include a perceived lack of analytical power and justification behind the chosen objectives.[18]

The MDGs lack strong objectives and indicators for within-country equality, despite significant disparities in many developing nations.[18][19]

Further critique of the MDGs is that the mechanism being used is that they seek to introduce local change through external innovations supported by external financing. The counter proposal being that these goals are better achieved by community initiative, building from resources of solidarity and local growth within existing cultural and government structures.[20][21] iterative mobilization of local successes that have proven their effectiveness can scale up to address the larger need through human energy and existing resources using methodologies such as Participatory Rural Appraisal, Asset Based Community Development, or SEED-SCALE, originally developed under UNICEF and now tested in a number of countries over two decades.[22]

MDG 8 uniquely focuses on donor achievements, rather than development successes. The Commitment to Development Index, published annually by the Center for Global Development in Washington, D.C., is considered the best numerical indicator for MDG 8.[23] It is a more comprehensive measure of donor progress than official development assistance, as it takes into account policies on a number of indicators that affect developing countries such as trade, migration and investment.

Alleged lack of legitimacy

The entire MDG process has been accused of lacking legitimacy as a result of failure to include, often, the voices of the very participants that the MDGs seek to assist. The International Planning Committee for Food Sovereignty, in its Post 2015 thematic consultation document on MDG 1 states "The major limitation of the MDGs by 2015 was the lack of political will to implement due to the lack of ownership of the MDGs by the most affected constituencies".[24]

Human rights

According to Deneulin & Shahani the MDGs underemphasize local participation and empowerment (other than women’s empowerment).[18] FIAN International, a human rights organization focusing on the right to adequate food, contributed to the Post 2015 process by pointing out a lack of: "primacy of human rights; qualifying policy coherence; and of human rights based monitoring and accountability. "Without such accountability, no substantial change in national and international policies can be expected."[25]

Infrastructure

The MDGs were attacked for insufficient emphasis on environmental sustainability.[18] Thus, they do not capture all elements needed to achieve the ideals set out in the Millennium Declaration.[19]

Agriculture was not specifically mentioned in the MDGs even though most of the world's poor are farmers.[citation needed]

Human capital

MDG 2 focuses on primary education and emphasizes enrolment and completion. In some countries, primary enrolment increased at the expense of achievement levels. In some cases, the emphasis on primary education has negatively affected secondary and post-secondary education.[26]

Amir Attaran argued that goals related to maternal mortality, malaria and tuberculosis are impossible to measure and that current UN estimates lack scientific validity or are missing. Household surveys are the primary measure for the health MDGs. Attaran attacked them as poor and duplicative measurements that consume limited resources. Furthermore, countries with the highest levels of these conditions typically have the least reliable data collection. Attaran argued that without accurate measures, it is impossible to determine the amount of progress, leaving MDGs as little more than a rhetorical call to arms.[27]

MDG proponents such as McArthur and Sachs countered that setting goals is still valid despite measurement difficulties, as they provide a political and operational framework to efforts. With an increase in the quantity and quality of healthcare systems in developing countries, more data could be collected.[28] They asserted that non-health related MDGs were often well measured, and that not all MDGs were made moot by lack of data.

The attention to well being other than income helps bring funding to achieving MDGs.[18] Further MDGs prioritize interventions, establish obtainable objectives with useful measurements of progress despite measurement issues and increased the developed world’s involvement in worldwide poverty reduction.[29] MDGs include gender and reproductive rights, environmental sustainability, and spread of technology. Prioritizing interventions helps developing countries with limited resources make decisions about allocating their resources. MDGs also strengthen the commitment of developed countries and encourage aid and information sharing.[18] The global commitment to the goals likely increases the likelihood of their success. They note that MDGs are the most broadly supported poverty reduction targets in world history.[30]

Achieving the MDGs does not depend on economic growth alone. In the case of MDG 4, developing countries such as Bangladesh have shown that it is possible to reduce child mortality with only modest growth with inexpensive yet effective interventions, such as measles immunisation.[31] Still, government expenditure in many countries is not enough to meet the agreed spending targets.[32] Research on health systems suggests that a "one size fits all" model will not sufficiently respond to the individual healthcare profiles of developing countries; however, the study found a common set of constraints in scaling up international health, including the lack of absorptive capacity, weak health systems, human resource limitations, and high costs. The study argued that the emphasis on coverage obscures the measures required for expanding health care. These measures include political, organizational, and functional dimensions of scaling up, and the need to nurture local organizations.[33]

Fundamental issues such as gender, the divide between the humanitarian and development agendas and economic growth will determine whether or not the MDGs are achieved, according to researchers at the Overseas Development Institute (ODI).[34][35][36]

According to D+C Development and Cooperation magazine, MDG 7 is still far from being reached. Since national governments often cannot provide the necessary infrastructure, civil society in some countries organised and worked on sanitation.[37] For instance, in Ghana an umbrella organisation called CONIWAS (Coalition of NGOs in Water and Sanitation), enlisted more than 70 member organisations to provide access to water and sanitation.

The International Health Partnership (IHP+) aimed to accelerate MDG progress by applying international principles for effective aid and development in the health sector. In developing countries, significant funding for health came from external sources requiring governments to coordinate with international development partners. As partner numbers increased variations in funding streams and bureaucratic demands followed. By encouraging support for a single national health strategy, a single monitoring and evaluation framework, and mutual accountability, IHP+ attempted to build confidence between government, civil society, development partners and other health stakeholders.[38]

Equity

Further developments in rethinking strategies and approaches to achieving the MDGs include research by the Overseas Development Institute into the role of equity.[39] Researchers at the ODI argued that progress could be accelerated due to recent breakthroughs in the role equity plays in creating a virtuous circle where rising equity ensures the poor participate in their country's development and creates reductions in poverty and financial stability.[39] Yet equity should not be understood purely as economic, but also as political. Examples abound, including Brazil's cash transfers, Uganda's eliminations of user fees and the subsequent huge increase in visits from the very poorest or else Mauritius's dual-track approach to liberalisation (inclusive growth and inclusive development) aiding it on its road into the World Trade Organization.[39] Researchers at the ODI thus propose equity be measured in league tables in order to provide a clearer insight into how MDGs can be achieved more quickly; the ODI is working with partners to put forward league tables at the 2010 MDG review meeting.[39]

The effects of increasing drug use were noted by the International Journal of Drug Policy as a deterrent to the goal of the MDGs.[40]

Women's issues

Kabeer, Grown and Heyzer argued that increased focus on gender issues would accelerate MDG progress. Kabeer claimed that empowering women through access to paid work would help reduce child mortality.[41] In South Asian countries babies often suffered from low birth weight and high mortality due to limited access to healthcare and maternal malnutrition. Paid work could increase women's access to health care and better nutrition, reducing child mortality. Increasing female education and workforce participation increased these effects. Improved economic opportunities for women also decreased participation in the sex market, which decreased the spread of AIDS, MDG 6A.[41]

Grown asserted that although the resources, technology and knowledge existed to decrease poverty through improving gender equality, the political will was missing.[42] She argued that if donor and developing countries focused on seven "priority areas": increasing girls’ completion of secondary school, guaranteeing sexual and reproductive health rights, improving infrastructure to ease women’s and girl’s time burdens, guaranteeing women’s property rights, reducing gender inequalities in employment, increasing seats held by women in government, and combating violence against women, great progress could be made towards the MDGs.[42]

Kabeer and Heyzer believe that the current MDGs targets do not place enough emphasis on tracking gender inequalities in poverty reduction and employment as there are only gender goals relating to health, education, and political representation.[41][43] To encourage women’s empowerment and progress towards the MDGs, increased emphasis should be placed on gender mainstreaming development policies and collecting data based on gender.

Progress

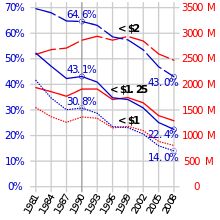

Progress towards reaching the goals has been uneven across countries. Brazil achieved many of the goals,[44] while others, such as Benin, are not on track to realize any.[45] The major successful countries include China (whose poverty population declined from 452 million to 278 million) and India.[46] The World Bank estimated that MDG 1A (halving the proportion of people living on less than $1 a day) was achieved in 2008 mainly due to the results from these two countries and East Asia.[47]

In the early 1990s Nepal was one of the world's poorest countries and remains South Asia's poorest country. Doubling health spending and concentrating on its poorest areas halved maternal mortality between 1998 and 2006. Its Multidimensional Poverty Index has seen the largest falls of any tracked country. Bangladesh has made some of the greatest improvements in infant and maternal mortality ever seen, despite modest income growth.[48]

Between 1990 and 2010 the population living on less than $1.25 a day in developing countries halved to 21%, or 1.2 billion people, achieving MDG1A before the target date, although the biggest decline was in China, which took no notice of the goal. However, the child mortality and maternal mortality are down by less than half. Sanitation and education targets will also be missed.[48]

Multilateral debt reduction

G‑8 Finance Ministers met in London in June 2005 in preparation for the Gleneagles Summit in July and agreed to provide enough funds to the World Bank, IMF and the African Development Bank (AfDB) to cancel an additional the remaining HIPC multilateral debt ($40 to $55 billion). Recipients would theoretically re-channel debt payments to health and education.[49]

The Gleaneagles plan became the Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI). Countries became eligible once their lending agency confirmed that the countries had continued to maintain the reforms they had implemented.[49]

While the World Bank and AfDB limited MDRI to countries that complete the HIPC program, the IMF's eligibility criteria were slightly less restrictive so as to comply with the IMF's unique "uniform treatment" requirement. Instead of limiting eligibility to HIPC countries, any country with per capita income of $380 or less qualified for debt cancellation. The IMF adopted the $380 threshold because it closely approximated the HIPC threshold.[50]

Sub-Saharan Africa

One success was to strengthen rice production. By the mid‑1990s rice imports reached nearly $1 billion annually. Farmers had not found suitable species that produce high yields. New Rice for Africa (NERICA), a high-yielding and well adapted strain was developed and introduced in areas including Congo Brazzaville, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Kenya, Mali, Nigeria, Togo and Uganda. Some 18 varieties of the hybrid species became available, enabling farmers to produce enough rice to feed their families and have extra to sell.[51]

The region also showed progress towards MDG 2. School fees that included Parent-Teacher Association and community contributions, textbook fees, compulsory uniforms and other charges took up nearly a quarter of a poor family’s income and led countries including Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Mozambique, Tanzania, and Uganda to eliminate such fees, increasing enrolment. For instance, in Ghana, public school enrolment in the most deprived districts soared from 4.2 million to 5.4 million between 2004 and 2005. In Kenya, primary school enrolment added 1.2 million in 2003 and by 2004, the number had climbed to 7.2 million.[52]

-

Proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day (1990, 2005)

-

Enrolment in primary education (1999, 2008)

-

Under-five mortality rate (1990, 2008)

-

Numbers of people living with, newly infected with and killed by HIV (1990-2008)

-

Proportion of population using an "improved water source" (1990, 2008)

-

External debt service payments as a proportion of export revenues (2000, 2008)

-

Internet users per hundred people (2003, 2008)

Malaria deaths declined by more than one-third, saving millions of lives.[53]

Although developed countries' aid rose during the Millennium Challenge, more than half went towards debt relief. Much of the remainder aid money went towards disaster relief and military aid. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2006), the 50 least developed countries received about one third of all aid that flows from developed countries.[40]

Funding commitment

Over the past 35 years, UN members have repeatedly "commit[ted] 0.7% of rich-countries' gross national income (GNI) to Official Development Assistance".[54] The commitment was first made in 1970 by the UN General Assembly.

The text of the commitment was:

Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net amount of 0.7 percent of its gross national product at market prices by the middle of the decade.[55]

European Union

In 2005 the European Union reaffirmed its commitment to the 0.7% aid targets, noting that "four out of the five countries, which exceed the UN target for ODA of 0.7%, of GNI are member states of the European Union".[56] Further, the UN "believe[s] that donors should commit to reaching the long-standing target of 0.7 percent of GNI by 2015".[55]

United States

However, the United States as well as other nations disputed the Monterrey Consensus that urged "developed countries that have not done so to make concrete efforts towards the target of 0.7% of gross national product (GNP) as ODA to developing countries".[57][58]

Attempts to increase U.S. political attention to the Millennium Development Goals include The Borgen Project which worked with then Senator Barack Obama on the Global Poverty Act, a bill requiring the White House to develop a strategy for achieving the goals. The bill did not pass, despite Obama's two terms as US President.[59][60]

The US consistently opposed setting specific foreign-aid targets since the UN General Assembly first endorsed the 0.7% goal in 1970.[61]

OECD

Many Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations, did not donate 0.7% of their GNI. Some nations' contributions fell far short of 0.7%.[62]

The Australian government committed to providing 0.5% of GNI in International Development Assistance by 2015-2016.[63]

Review Summit 2010

A major conference was held at UN headquarters in New York on 20–22 September 2010 to review progress. The conference concluded with the adoption of a global action plan to accelerate progress towards the eight anti-poverty goals. Major new commitments on women's and children's health, poverty, hunger and disease ensued.

Improvements

Improving living conditions in developing countries may encourage healthy workers not to move to other places that offer a better lifestyle.[64]

Cuba, itself a developing country, played a significant role in providing medical personnel to other developing nations; it has trained more than 14,500 medical students from 30 different countries at its Latin American School of Medicine in Havana since 1999. Moreover, some 36,000 Cuban physicians worked in 72 countries, from Europe to Southeast Asia, including 31 African countries, and 29 countries in the Americas. Countries such as Honduras, Guatemala, and Nicaragua benefit from Cuban assistance.[65]

Post 2015 development agenda

Although there has been major advancements and improvements achieving some of the MDGs even before the deadline of 2015, the progress has been uneven between the countries. In 2012 the UN Secretary-General established the "UN System Task Team on the Post-2015 UN Development Agenda", bringing together more than 60 UN agencies and international organizations to focus and work on sustainable development.[66]

At the MDG Summit, UN Member States discussed the Post-2015 Development Agenda and initiated a process of consultations. Civil society organizations also engaged in the post-2015 process, along with academia and other research institutions, including think tanks.[67]

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have been proposed as targets relating to future international development once they expire at the end of 2015.

On 31 July 2012, Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon appointed 26 public and private leaders to advise him on the post-MDG agenda.[68]

In 2014, the UN's Commission on the Status of Women agreed on a document that called for the acceleration of progress towards achieving the millennium development goals, and confirmed the need for a stand-alone goal on gender equality and women's empowerment in post-2015 goals, and for gender equality to underpin all of the post-2015 goals.[69]

Related activities/organizations

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (December 2009) |

The United Nations Millennium Campaign is a UNDP campaign to increase support for the Millennium Development Goals. The Millennium Campaign targets intergovernmental, government, civil society organizations and media at global and regional levels.

The Millennium Promise Alliance, Inc. (or simply the "Millennium Promise") is a U.S.-based non-profit organization founded in 2005 by Jeffrey Sachs and Ray Chambers.[70] Millennium Promise coordinates the Millennium Villages Project in partnership with Columbia's Earth Institute and UNDP; it aims to demonstrate MDG feasibility through an integrated, community-led approach. As of 2012 the Millennium Villages Project operated in 14 sites across 10 countries in sub-Saharan Africa.[71]

The Global Poverty Project[72] is an international education and advocacy organisation that encourages MC support in English-speaking countries.

The Micah Challenge is an international campaign that encourages Christians to support the Millennium Development Goals. Their aim is to "encourage our leaders to halve global poverty by 2015".[73]

The Youth in Action EU Programme "Cartoons in Action" project[74] created animated videos about MDGs,[75] and a YouTube channel[76] and videos about MDG targets using Arcade C64 videogames.[75][77]

Education

Accessing Development Education is a web portal. It provides relevant information about development and global education and helps educators share resources and materials that are most suitable for their work.[78]

The Teach MDGs European project aims to increase MDG awareness and public support by engaging teacher training institutes, teachers and pupils in developing local teaching resources that promote the MDGs with a focus on sub-Saharan Africa.[78]

Global Education Magazine[79] is an initiative launched by the teaching team that formulated the proposal most voted in the group “Sustainable Development for the Eradication of Poverty in Rio+20”.[80] It is supported by UNESCO and UNHCR and aims to create a common place to disseminate transcultural, transpolitical, transnational and transhumanist knowledge.

UN Goals

UN Goals is a global project dedicated to spreading knowledge of MDG through various internet and offline awareness campaigns.

Libraries and the Millennium Development Goals

Librarians and others in the information professions are in a unique position to help achieve the Millennium Development Goals. It is often the dissemination of key information, e.g., about health, that changes daily life and can affect an entire community.

Millennium Development Goals are not only for the developing world. Maret (2011) specifically addresses how U.S. public libraries can help the United States meet the goals.[81]

Albright and Kwooya (2007) report that cultural and financial barriers in Sub-Saharan Africa impede LIS education programs. As a result, MDG goals for poverty, healthcare, and education fall short. High rates of HIV/AIDS, and escalating child and maternal mortality are the direct result of poverty and substandard medical care. Limited instruction in information access and exchange contributes to this ongoing dilemma.[82]

See also

- 8 (2008), a series of eight short films about the eight MDGs

- Debt relief

- Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities

- International development

- Official development assistance (ODA)

- Precaria (country)

- Seoul Development Consensus

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

- Post-2015 Development Agenda

- Development Cooperation Issues

- Development Cooperation Stories

- Development Cooperation Testimonials

References

- ^ [1], United Nations Millennium Development Goals website, retrieved 21 September 2013

- ^ Background page, United Nations Millennium Development Goals website, retrieved 16 June 2009

- ^ An Introduction to the Human Development and Capability Approach: Freedom and Agency'

- ^ "The Political Economy of the MDGs: Retrospect and Prospect for the World's Biggest Promise"

- ^ "The Millennium Development Goals Report"

- ^ "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". Un.org. 20 May 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Tracking the Millennium Development Goals". Mdg Monitor. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "List of goals, targets, and indicators" (PDF). Siteresources.worldbank.org. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ http://content.undp.org/go/cms-service/stream/asset/;jsessionid=aMgXw9lbMbH4?asset_id=2620072

- ^ "Goal :: Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Achieve Universal Primary Education". Mdg Monitor. 15 May 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Promote Gender Equality and Empower Women". Mdg Monitor. 30 April 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Reduce Child Mortality". Mdg Monitor. 16 May 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Improve Maternal Health". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Combat HIV/AIDS, Malaria and Other Diseases". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Ensure Environmental Sustainability". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal :: Develop a Global Partnership for Development". Mdg Monitor. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Deneulin, Séverine; Shahani, Lila (2009). An introduction to the human development and capability approach freedom and agency. Sterling, Virginia Ottawa, Ontario: Earthscan International Development Research Centre. ISBN 9781844078066.

- ^ a b Can the MDGs provide a pathway to social justice?: The challenge of intersecting inequalities. 2010. Naila Kabeer for Institute of Development Studies.

- ^ Dani Rodrik, One Economics, Many Recipes: Globalization, Institutions, and Economic Growth (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008)

- ^ Stephen Marglin, The Dismal Science: How Thinking Like an Economist Undermines Community (Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 2008)

- ^ Daniel C. Taylor, Carl E. Taylor, Jesse O. Taylor, ‘’Empowerment on an Unstable Planet: From Seeds of Human Energy to a Scale of Global Change’’ (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012) p.25-33.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ "Position International Planning Committee on Food Sovereignty Informal Thematic Consultation Hunger, Food and Nutrition Post 2015, CSA actors" (PDF). Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ FIAN International. "Post 2015 Thematic Consultation". Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ^ Waage, Jeff; et al. (18 September 2010). "The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after 2015". The Lancet. 376 (9745): 991–1023. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61196-8.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|first=(help)(registration required) - ^ Attaran, Amir (October 2005). "An Immeasurable Crisis? A Criticism of the Millennium Development Goals and Why They Cannot Be Measured". PLOS Medicine. 2 (10): 318. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020318.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020379, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1371/journal.pmed.0020379instead. - ^ Andy Haines and Andrew Cassels. 2004. "Can The Millennium Development Goals Be Attained?" BMJ: British Medical Journal, Vol. 329, No. 7462 (Aug. 14, 2004), pp. 394-397

- ^ United Nations. 2006. "The Millennium Development Goals Report: 2006." United Nations Development Programme, www.undp.org/publications/MDGReport2006.pdf (accessed January 2, 2008).

- ^ [2][dead link]

- ^ "The Feasibility of Financing Sectoral Development Targets". Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Subramanian, Savitha; Joseph Naimoli; Toru Matsubayashi; David Peters (2011). "Do We Have the Right Models for Scaling Up Health Services to Achieve the Millennium Development Goals?". BMC Health Services Research. 11 (336). doi:10.1186/1472-6963-11-336.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Gender and the MDGs". ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "MDGs and the humanitarian-development divide". ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Economic Growth and the MDGs". ODI Briefing Paper. Overseas Development Institute. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ "Yirenya-Tawiah/Tweneboah Lawson: Civil society is paving the way towards better sanitation in Ghana - Development and Cooperation - International Journal". Dandc.eu. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "IHP+ The International Health Partnership". Internationalhealthpartnership.net. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b c d Vandemoortele, Milo (2010) "The MDGs and Equity", Overseas Development Institute.

- ^ a b Singer, M. 2008. "Drugs and Development: The Global Impact of Drug Use and Trafficking on Social and Economic Development. International Journal of Drug Policy 19 (6):467-478.

- ^ a b c Kabeer, Naila. 2003. Gender Mainstreaming in Poverty Eradication and the Millennium Development Goals: A Handbook for Policy-Makers and Other Stakeholders. Commonwealth Secretariat.

- ^ a b Grown, Caren. 2005. "Answering the Skeptics: Achieving Gender Equality and the Millennium Development Goals". Development 48(3): 82–86.

- ^ Noeleen Heyzer. 2005. "Making the Links: Women's Rights and Empowerment Are Key to Achieving the Millennium Development Goals". Gender and Development, Vol. 13, No. 1, Millennium Development Goals (March 2005), pp. 9-12

- ^ "Brazil: Quick Facts". MDG Monitor. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Benin: Quick Facts". MDG Monitor. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Halving Global Poverty" (PDF). Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ Chen, Shaohua and Martin Ravallion, (29 February 2012) "An Update to the World Bank’s Estimates of Consumption Poverty in the Developing World" Development Research Group, World Bank, Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ^ a b "Poverty: Growth or safety net?". The Economist. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ a b E. Carrasco, C. McClellan, & J. Ro (2007) "Foreign Debt: Forgiveness antetretetred Repudiation" University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development E-Book

- ^ E. Carrasco, C.McClellan, & J. Ro (2007), "Foreign Debt: Forgiveness antetretetred Repudiation" University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development E-Book[dead link]

- ^ "Goal :: Tracking the Millennium Development Goals". Mdg Monitor. 1 November 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Goal: Tracking the Millennium Development Goals". MDG Monitor. 1 November 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Free exchange: The next frontier". The Economist. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ "Press Archive". UN Millennium Project. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Publications". UN Millennium Project. 1 January 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "External Relations Council, Brussels 24 May 2005" (PDF). Unmillenniumproject.org. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "United Nations Report of the International Conference on Financing for Development" (PDF). Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ [3][dead link]

- ^ "Borgen Back from Capitol Hill". Borgen Project News. 8 June 2007. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Highlight of Borgen's 2006 Congressional Meetings". Borgen Project News. 10 December 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Bush Balks at Pact to Fight Poverty". BusinessWeek online. 2 September 2005.

- ^ "Poverty Can Be Halved If Efforts Are Coupled with Better Governance, says TI" (PDF). UN Millennium Project. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ [4][dead link]

- ^ Haines, Andy; Andrew Cassels (August 2004). "Can the Millennium Development Goals Be Attained?". British Medical Journal. 329(7462).

- ^ Huish, Robert (2009). "Canadian Foreign Aid for Global Health: Human Secruity Opportunity Lost". Can Foreign Policy (1192–6422): 60.

- ^ "Millennium Development Goals and post-2015 Development Agenda". The United Nations. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ^ "United Nations Millennium Development Goals". Un.org. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "UN Secretary-General Appoints High-Level Panel on Post-2015 Development Agenda" (PDF). Un.org. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/mar/23/campaigners-welcome-agreement-un-gender-csw-talks

- ^ "Overview". Millennium Promise. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Millennium Villages". Millennium Villages. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Welcome | Netherlands". Global Poverty Project. 17 May 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "Home". Micah Challenge. 9 October 2012. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ "Cartoons in action Progetto Gioventù in Azione finanziato dallANG - Agenzia Nazionale per i Giovani Youth in Action EU Programme. Il presente progetto è finanziato con il sostegno della Commissione europea. | Wix.com". Socialab.wix.com. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b R.I.P. giovane e dolce Melissa. "Cartoons inAction". YouTube. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ [Millennium Development Goals playlist on YouTube "8 gol x 8 Millennium Development Goals"]. YouTube. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ "MDGs". YouTube. Retrieved 14 October 2012.

- ^ a b "Welcome to the Development Education online Depository!". Developmenteducation.info. Retrieved 18 October 2012.

- ^ "(2012). The Humanist Quantum Interference: Towards the "Homo Conscienciatus". Javier Collado Ruano, October 17th: International Day for the Eradication of Poverty. ISSN 2255-033X". :. 17 October 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ "NGO Educar para Vivir (2012)". Globaleducationmagazine.com. 16 June 2012. Retrieved 6 February 2014.

- ^ Maret, S. (2011). True community: connecting the Millennium Development Goals to public library services in the United States. Information, Society and Justice, 4(2), 29-55.

- ^ Albright, K., & Kawooya, D. (2007). Libraries in the time of AIDS: African perspectives and recommendations for a revised model of LIS education. International Information And Library Review, 39(Library and Information Science Education in Developing Countries), 109-120.

External links

- Official website

- [5] One page chart of the status of the MDGs at 2013

- Eradicate Extreme Poverty and Hunger by 2015 | UN Millennium Development Goal curated by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Michigan State University

- Ensure Environmental Sustainability by 2015 | UN Millennium Development Goal curated by the Center for Latin American and Caribbean Studies at Michigan State University

- Gillian Sorensen, Senior Advisor to the United Nations Foundation, discusses UN Millennium Development Goals

⇒ The Vrinda Project Channel - videos on the work in progress for the achievement of the MDGs connected to the Wikibook

⇒ The Vrinda Project Channel - videos on the work in progress for the achievement of the MDGs connected to the Wikibook  Development Cooperation Handbook

Development Cooperation Handbook- The Millennium Development Goals in Asia and the Pacific: 12 Things to Know Asian Development Bank