Kombucha: Difference between revisions

→Health effects: correct passage to make the Health effects section compliant with MEDRS and NPOV |

→top: expand lead to comply with NPOV and information in the body of the article |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

'''Kombucha''' (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly [[effervescent]] [[Fermentation (food)|fermented drink]] of sweetened [[black tea|black]] and/or [[green tea|green]] tea that is used as a [[functional food]]. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a [[SCOBY|symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast]] (SCOBY). |

'''Kombucha''' (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly [[effervescent]] [[Fermentation (food)|fermented drink]] of sweetened [[black tea|black]] and/or [[green tea|green]] tea that is used as a [[functional food]]. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a [[SCOBY|symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast]] (SCOBY). |

||

Kombucha tea is often referred to as a beneficial health drink because of its combined [[antioxidant]] activity, and its [[probiotic]] properties produced by live bacteria or [[metabolites]] of bacteria during [[fermentation]]. Over the past 20 years or so, scientific research has indicated the potential beneficial effects of tea and fermented tea ([[black tea]]) for health, the latter of which is considered meaningful because of its world-wide popularity. The antioxidative properties of black tea have been displayed [[in vitro]] and [[in vivo]] "by its ability to inhibit [[free radical]] generation, scavenge free radicals, and [[chelate]] transition [[metal ions]]." <ref name=Farnworth>{{cite journal | url = http://www.kombuchashare.com/research/Tea, Kombucha, and health.pdf | publisher = Elsevier Science Ltd. | title = Food Research International | work = Tea, Kombucha, and Health: A Review | authors = C. Dufresne, E. Farnworth | pages = 409-421 | date = July 2000 | work = | volume = 33 | issue = 6 | pages = 409-421 | doi = 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3}}</ref><ref name=Jayabalan>{{cite journal |first1= R |last1= Jayabalan |first2= RV |last2= Malbaša |first3= ES |last3= Lončar |first4= JS |last4= Vitas |first5= M |last5= Sathishkumar |date= July 2014 |title= A Review on Kombucha Tea — Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus |journal= [[Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety]] |volume= 13 |issue= 4 |pages= 538–50 |doi= 10.1111/1541-4337.12073 | quote="a source of pharmacologically active molecules, an important member of the antioxidant food group, and a functional food with potential beneficial health properties."}}</ref><ref name = NBC>{{cite web | url = http://www.nbcnews.com/id/36571884/ns/health-diet_and_nutrition/t/trendy-fizzy-drink-mushrooming/#.VYLYZWt5mK1 | publisher = NBCnews.com | title = Trendy Fizzy Drink is Mushrooming | author = Janet Helm, R.D. | quote = While kombucha may not be the miracle that some claim, it does represent an intriguing marriage of antioxidant-rich tea and probiotics. | date = April 23, 2010 | accessdate= June 18, 2015}}</ref> |

|||

Although consuming kombucha has been claimed to have beneficial health effects, there is no high quality evidence to support these claims.<ref name=Jayabalan/><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Greenwalt|first1=CJ|last2=Steinkraus|first2=KH|last3=Ledford|first3=RA|title=Kombucha, the fermented tea: microbiology, composition, and claimed health effects.|journal=Journal of food protection|date=July 2000|volume=63|issue=7|pages=976-81|pmid=10914673}}</ref> [[Adverse effect]]s related to drinking kombucha have been documented, and reports have raised concern over the potential for contamination during home preparation.<ref name=Jayabalan/> |

|||

While there is scientific evidence that supports the kombucha's antioxidative and probiotic activity as a health drink, there are no [[Clinical trial|random clinical trial]]s that support its [[Curative therapy|curative]] claims. There have also been a small number of random anecdotal [[case reports]] that have raised some concern over [[lactic acidosis]] and other potentially harmful effects linked to unsafe practices during home preparation, such as lead contamination from leaching ceramic containers during fermentation.<ref name=Jayabalan/> |

|||

== History == |

== History == |

||

Revision as of 23:35, 20 June 2015

Kombucha (Russian: chaynyy grib (чайный гриб), Chinese: chájūn (茶菌), Korean: hongchabeoseotcha (홍차버섯차), Japanese: kōcha-kinoko (紅茶キノコ)), is a lightly effervescent fermented drink of sweetened black and/or green tea that is used as a functional food. It is produced by fermenting the tea using a symbiotic colony of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY).

Kombucha tea is often referred to as a beneficial health drink because of its combined antioxidant activity, and its probiotic properties produced by live bacteria or metabolites of bacteria during fermentation. Over the past 20 years or so, scientific research has indicated the potential beneficial effects of tea and fermented tea (black tea) for health, the latter of which is considered meaningful because of its world-wide popularity. The antioxidative properties of black tea have been displayed in vitro and in vivo "by its ability to inhibit free radical generation, scavenge free radicals, and chelate transition metal ions." [1][2][3]

While there is scientific evidence that supports the kombucha's antioxidative and probiotic activity as a health drink, there are no random clinical trials that support its curative claims. There have also been a small number of random anecdotal case reports that have raised some concern over lactic acidosis and other potentially harmful effects linked to unsafe practices during home preparation, such as lead contamination from leaching ceramic containers during fermentation.[2]

History

Kombucha originated 5,000 years ago in China, where it was known as "Divine Che" (Divine Tea). In 220 BC, during the Tsing Dynasty, the tea was highly valued because it was thought to be an "energizing" and "detoxifying" agent. In 414 AD, a Korean doctor named Kombu brought the tea to the Emperor of Japan as an aid for his digestive difficulties. The drink later spread to east Russia around 1900, and from there, to Europe.[4][5]

In Russian, the kombucha culture is called chainyy grib чайный гриб (literally "tea fungus/mushroom"), and the fermented drink is called chainyy grib, grib ("fungus; mushroom"), or chainyy kvas чайный квас ("tea kvass"). Kombucha was highly popular and seen as a health food in China in the 1950s and 1960s. Many families grew kombucha at home.[citation needed]

Commercially bottled kombucha became available in the late 1990s.[6]

In 2010, elevated alcohol levels were found in many kombucha products, leading retailers including Whole Foods to temporarily pull the drinks. In response, kombucha suppliers reformulated their products to have lower alcohol levels.[7]

By 2014, annual sales of kombucha beverages exceeded $120 million.[8]

Etymology

In Japan, Konbucha (昆布茶, "kelp tea") refers to a different beverage made from dried and powdered kombu (an edible kelp from the Laminariaceae family).[9] For the origin of the English word kombucha, in use since at least 1991[10] and of uncertain etymology,[11] the American Heritage Dictionary suggests: "Probably from Japanese kombucha, tea made from kombu (the Japanese word for kelp perhaps being used by English speakers to designate fermented tea due to confusion or because the thick gelatinous film produced by the kombucha culture was thought to resemble seaweed)."[12]

The Japanese name for what English speakers know as kombucha is kōcha kinoko 紅茶キノコ (literally, 'black tea mushroom'), compounding kōcha "black tea" and kinoko 茸 "mushroom; toadstool". The Chinese names for kombucha are hóngchájùn 红茶菌 ('red tea fungus'), cháméijūn 茶黴菌 ('tea mold'), or hóngchágū 红茶菇 ('red tea mushroom'), with jūn 菌 'fungus, bacterium or germ' (or jùn 'mushroom'), méijūn 黴菌 'mold or fungus', and gū 菇 'mushroom'. ("Red tea", 紅茶, in Chinese languages corresponds to English "black tea".)

A 1965 mycological study called kombucha "tea fungus" and listed other names: "teeschwamm, Japanese or Indonesian tea fungus, kombucha, wunderpilz, hongo, cajnij, fungus japonicus, and teekwass".[13] Some further spellings and synonyms include combucha and tschambucco, and haipao, kargasok tea, kwassan, Manchurian fungus or mushroom, spumonto, as well as the misnomers champagne of life, and chai from the sea.[14]

Health effects

While there is scientific evidence that supports kombucha's antioxidative and probiotic activity as a health drink, there are no random clinical trials that support its curative or therapeutical claims. There have also been a small number of random anecdotal case reports that have raised some concern over lactic acidosis, and other potentially harmful effects linked to unsafe practices during home preparation, such as lead contamination from leaching ceramic containers during fermentation.[2] Brewers have been cautioned to avoid over-fermentation.[15]

Chemical and biological properties

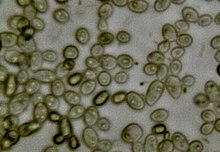

A kombucha culture is a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), containing Acetobacter (a genus of acetic acid bacteria) and one or more yeasts, which form a zoogleal mat. In Chinese, the microbial culture is called haomo in Cantonese, or jiaomu in Mandarin, (Chinese: 酵母; lit. 'fermentation mother').

Kombucha cultures may contain one or more of the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Candida stellata, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, Torulaspora delbrueckii, and Zygosaccharomyces bailii.

Although the bacterial component of a kombucha culture comprises several species, it almost always includes Gluconacetobacter xylinus (formerly Acetobacter xylinum), which ferments the alcohol(s) produced by the yeast(s) into acetic acid, increasing the acidity while limiting the kombucha's alcoholic content. The number of bacteria and yeasts that were found to produce acetic acid increased for the first four days of fermentation, decreasing thereafter. Sucrose gets broken down into fructose and glucose, and the bacteria and yeast convert the glucose and fructose into gluconic acid and acetic acid, respectively.[5] G. xylinum is responsible for most or all of the physical structure of a kombucha mother, and has been shown to produce microbial cellulose,[16] likely due to selection over time for firmer and more robust cultures by brewers.

Along with multiple species of yeast and bacteria, Kombucha contains organic acids, enzymes, amino acids, and polyphenols they produce. The exact quantities of these items vary between samples, but may contain: acetic acid, ethanol, gluconic acid, glucuronic acid, glycerol, lactic acid, usnic acid and B-vitamins.[17][18][19] Kombucha has also been found to contain about 1.51 mg/mL of vitamin C.[20]

According to the American Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, some kombucha products contain more than 0.5% alcohol by volume, but some contain less.[21]

Kombucha tea has antioxidant properties and has been called a functional food.[2]

Other uses

Kombucha culture, when dried, becomes a leather-like textile known as a microbial cellulose that can be molded onto forms to create seamless clothing.[22][23] Using different broth mediums such as coffee, black tea, and green tea to grow the kombucha culture results in different textile colors, although the textile can also by dyed using plant-based dyes.,[24] Different growth mediums and dyes also change the textile's feel and texture.[25][24] The kombucha textile is similar to cellulose and is sustainable and compostable. London-based fashion designer Suzanne Lee presented kombucha textiles in shoes and clothing in 2011[26] and in 2014, designer Sacha Laurin debuted a clothing collection made entirely out of kombucha textile.[25]

See also

References

- ^ Kombucha, and health.pdf "Food Research International" (PDF). 33 (6). Elsevier Science Ltd. July 2000: 409–421. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Cite uses deprecated parameter|authors=(help) - ^ a b c d Jayabalan, R; Malbaša, RV; Lončar, ES; Vitas, JS; Sathishkumar, M (July 2014). "A Review on Kombucha Tea — Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 13 (4): 538–50. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12073.

a source of pharmacologically active molecules, an important member of the antioxidant food group, and a functional food with potential beneficial health properties.

- ^ Janet Helm, R.D. (April 23, 2010). "Trendy Fizzy Drink is Mushrooming". NBCnews.com. Retrieved June 18, 2015.

While kombucha may not be the miracle that some claim, it does represent an intriguing marriage of antioxidant-rich tea and probiotics.

- ^ Dufresne, C.; Farnworth, E. (2000). "Tea, Kombucha, and health: a review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409–421. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3. ISSN 0963-9969.

- ^ a b Sreeramulu, G; Zhu, Y; Knol, W (2000). "Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (6): 2589–94. doi:10.1021/jf991333m. PMID 10888589.

- ^ Wollan, Malia (24 March 2010). "A Strange Brew May Be a Good Thing". NYTimes. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Rothman, Max (2 May 2013). "'Kombucha Crisis' Fuels Progress". Bevnet. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Carr, Coeli (9 August 2014). "Kombucha cha-ching: A probiotic tea fizzes up strong growth". CNBC. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Wong, Crystal. (12 July 2007). "U.S. 'kombucha': Smelly and No Kelp". Japan Times. Retrieved 14 June 2015..

- ^ O'Neill, Molly (28 December 1994). "A Magic Mushroom Or a Toxic Fad?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Algeo, John; Algeo, Adele (1997). "Among the New Words". American Speech. 72 (2): 183–97. doi:10.2307/455789. JSTOR 455789.

- ^ American Heritage Dictionary, 4th ed. 2000, updated 2009, Houghton Mifflin Company. kombucha, TheFreeDictionary.com.

- ^ Hesseltine, C. W. (1965). "A Millennium of Fungi, Food, and Fermentation". Mycologia. 57 (2): 149–97. doi:10.2307/3756821. JSTOR 3756821. PMID 14261924.

- ^ "Kombucha". Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. 22 May 2014. Retrieved June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Nummer, Brian A. (2013). "Kombucha Brewing Under the Food and Drug Administration Model Food Code: Risk Analysis and Processing Guidance". Journal of Environmental Health. 76 (4).

- ^ Nguyen, VT; Flanagan, B; Gidley, MJ; Dykes, GA (2008). "Characterization of cellulose production by a gluconacetobacter xylinus strain from kombucha". Current Microbiology. 57 (5): 449–53. doi:10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3. PMID 18704575.

- ^ Teoh, AL; Heard, G; Cox, J (2004). "Yeast ecology of kombucha fermentation". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 95 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020. PMID 15282124.

- ^ Dufresne, C; Farnworth, E (2000). "Tea, kombucha, and health: A review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3.

- ^ Velicanski, A; Cvetkovic, D; Markov, S; Tumbas, V; Savatovic, S (2007). "Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha". Acta Periodica Technologica (38): 165–72. doi:10.2298/APT0738165V.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Bauer-Petrovska, B; Petrushevska-Tozi, L (2000). "Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the kombucha drink". International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 35 (2): 201–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.2000.00342.x.

- ^ "Kombucha FAQs" (PDF). Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Grushkin, Daniel (17 February 2015). "Meet the Woman Who Wants to Grow Clothing in a Lab". Popular Science. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Oiljala, Leena (9 September 2014). "BIOCOUTURE Creates Kombucha Mushroom Fabric For Fashion & Architecture". Pratt Institute. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ a b Hinchliffe, Jessica (25 September 2014). "'Scary and gross': Queensland fashion students grow garments in jars with kombucha". ABCNet.net.au. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ a b Mandelkern, India (22 Nov 2013). "Can Kombucha Couture Save the World?". Huffington Post. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ "Suzanne Lee: Grow your own clothes". TED2011. March 2011.

Further reading

- Dasgupta A, Sepulveda JL (2013). Other Supplements that Cause Liver Damage. Elsevier. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-12-415858-0.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Frank, Günther W. (1995). Kombucha: Healthy Beverage and Natural Remedy from the Far East, Its Correct Preparation and Use. Steyr: Pub. House W. Ennsthaler. ISBN 978-3-85068-337-1.