Hinduism in the West

| |

|

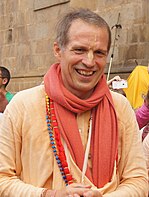

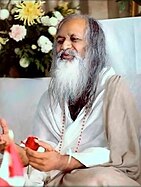

(Counterclockwise from top) Ganesh Temple in Flushing, Queens, New York City, the oldest Hindu temple in the Western Hemisphere; Ratha Yatra in Russia; The Holi Festival in March 2013 at the Sri Sri Radha Krishna Temple in Utah County, Utah; image of Sacinandana Swami; | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 6.8 million (0.49% of the population)[1][2] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 3,310,000 | |

| 1,021,000 | |

| 828,195 | |

| 684,002 | |

| 180,000 | |

| 150,000 | |

| 130,000 | |

| 123,534 | |

| 150,000 | |

| 50,000 | |

| 40,000 | |

| 30,000 | |

| 10,000 | |

| Religions | |

| Hinduism | |

| Scriptures | |

| Bhagavad Gita and Vedas | |

| Languages | |

|

Predominant spoken languages: | |

The reception of Hinduism in the Western world begins in the 19th century, at first at an academic level of religious studies and antiquarian interest in Sanskrit. Only after World War II does Hinduism acquire a presence as a religious minority in western nations, partly due to immigration, and partly due to conversion, the latter especially in the context of the 1960s to 1970s counter-culture, giving rise to a number of Hinduism-inspired new religious movements sometimes also known as "Neo-Hindu" or "export Hinduism".

History

Colonial period

During the British colonial period the British substantially influenced Indian society, but India also influenced the western world. An early champion of Indian-inspired thought in the West was Arthur Schopenhauer who in the 1850s advocated ethics based on an "Aryan-Vedic theme of spiritual self-conquest", as opposed to the ignorant drive toward earthly utopianism of the superficially this-worldly "Jewish" spirit.[6] Helena Blavatsky moved to India in 1879, and her Theosophical Society, founded in New York in 1875, evolved into a peculiar mixture of Western occultism and Hindu mysticism over the last years of her life.

The sojourn of Vivekananda to the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago in 1893 had a lasting effect. Vivekananda founded the Ramakrishna Mission, an Indian religious missionary organization still active today.

Hinduism-inspired elements in Theosophy were also inherited by the spin-off movements of Ariosophy and Anthroposophy and ultimately contributed to the renewed New Age boom of the 1960s to 1980s, the term New Age itself deriving from Blavatsky's 1888 The Secret Doctrine.

In the early 20th century, Western occultists influenced by Hinduism include Maximiani Portaz – an advocate of "Aryan Paganism" – who styled herself Savitri Devi and Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, founder of the German Faith Movement. It was in this period, and until the 1920s, that the swastika became a ubiquitous symbol of good luck in the West before its association with the Nazi Party became dominant in the 1930s. In 1920, Yogananda came to the United States as India's delegate to an International Congress of Religious Liberals convening in Boston;[7] the same year he founded the Self-Realization Fellowship (SRF) to disseminate worldwide his teachings on India's ancient practices and philosophy of Yoga and its tradition of meditation.[8] In unrelated developments, during the same time Jiddu Krishnamurti, a South Indian Brahmin, was promoted as the "vehicle" of the messianic entity Maitreya, the so-called World Teacher, by the Theosophical Society.

Another early Hindu teacher received in the west was Sri Aurobindo (d. 1950), who had considerable influence on western "integral" esotericism, traditionalism ("Perennialism") or spirituality in the tradition of René Guénon, Julius Evola, Rudolf Steiner, etc.

Neo-Hindu movements 1950s–1980s

During the 1960s to 1970s counter-culture, Sathya Sai Baba (Sathya Sai Organization), A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (ISKCON or "Hare Krishna"), Guru Maharaj Ji (Divine Light Mission) and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Transcendental Meditation movement) attracted a notable western following, founding religious or quasi-religious movements that remain active into the present time. This group of movements founded by charismatic persons with a corpus of esoteric writings, predominantly in English, is classed as founding, proselytizing religions, or "guru-ism" by Michaels (1998).[9]

Hatha Yoga was popularized from the 1960s by B.K.S. Iyengar, K. Pattabhi Jois and others. However, western practice of Yoga has mostly become detached from its religious or mystic context and is predominantly practiced as exercise or as alternative medicine.[10]

Since the 1980s, Mata Amritanandamayi and Mother Meera (the "Divine Mother", self-identifying as an avatar of Shakti) have been active in the west.

Hindu migration to Western countries

Substantial emigration from the (predominantly Hindu) Republic of India has taken place since the 1970s, with several million Hindus from Pakistan & Bangladesh moving to North America and Western Europe fleeing religious persecution. In 1913, A.K. Mozumdar became the first Indian-born person to earn U.S. citizenship.[11]

The largest immigrant (Deshi) Hindu communities in the west are found in the United States (3.23 million), the United Kingdom (0.84 million), Canada (0.50 million), Australia (0.44 million), New Zealand (0.09 million), besides smaller communities in other countries of Western Europe, (Netherlands 0.21 M, Italy 0.18 M, France 0.12 M, Germany 0.1 M, Spain 0.03 M and Switzerland 0.03 M). Much of the Hindu presence in Canada is due to the Tamil diaspora as a result of the Sri Lankan civil war, as well as Gujarati and Punjabi immigrants from India - along with a small Hindu community from the Caribbean.

Hinduism-derived elements in popular culture

Growing out of the enthusiasm for Hinduism in 1960s counterculture, modern western popular culture has adopted certain elements ultimately based in Hinduism which are not now considered necessarily practiced in a religious or spiritual setting. It is estimated that around 30 million Americans and 5 million Europeans regularly practice some form of Hatha Yoga, mainly as exercise.[12] In Australia, the number of practitioners is about 300,000.[13] In New Zealand, the number is also around 300,000.[14]

Author Kathleen Hefferon comments that "In the West, a more modernized "New Age" version of Ayurveda has recently gained popularity as a unique form of complementary and alternative medicine".[15]

"Vegetarianism, nonviolent ethics, yoga, and meditation—all have enjoyed spates of Occidental popularity in the last 40 years, often influenced by ISKCON directly, if not indirectly."[16][17]

See also

- Hindu reform movements

- Sanskrit in the West

- Esotericism in Germany and Austria

- Ramakrishna's impact

- Neo-Advaita

- Californian Hindu textbook controversy

- Category:Converts to Hinduism

- Hindu denominations

- Hindu Temple Society of North America, Flushing

- Hinduism in Australia

- Hinduism in Canada

- Hinduism in Europe

- Hinduism in New Zealand

- Hinduism in the United Kingdom

- Hinduism in the United States

- Indians in the New York City metropolitan area

- Invading the Sacred

- List of Hindu temples in the United States

- Organizations

References

- ^ "Hindu by country". globalreligiousfuture.org.

- ^ "ISCKON followers in the western world". krishna.org.

- ^ Johnson, Todd M.; Grim, Brian J. (2013). The World's Religions in Figures: An Introduction to International Religious Demography (PDF). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2015.

- ^ "International Yoga Day: How Swami Vivekananda helped popularise the ancient Indian regimen in the West". 12 January 2022.

- ^ Feuerstein, Georg (2002). The Yoga Tradition. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 600.

- ^ "Fragments for the history of philosophy", Parerga and Paralipomena, Volume I (1851).

- ^ Melton, J. Gordon; Baumann, Martin (2010). Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598842043.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (3 December 2010). "Sri Daya Mata, Guiding Light for U.S. Hindus, Dies at 96". The New York Times. New York.

- ^ Alex Michaels Archived 25 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine "Hinduism Past and Present" (2004) Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-08952-3, translated from German "Der Hinduismus" (1998) page 22

- ^ De Michelis, Elizabeth (2007). "A Preliminary Survey of Modern Yoga Studies" (PDF). Asian Medicine, Tradition and Modernity. 3 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1163/157342107X207182.

- ^ Indian American#Timeline

- ^ P. 250 Educational Opportunities in Integrative Medicine: The a to Z Healing Arts Guide and Professional Resource Directory By Douglas A. Wengell

- ^ "Yoga Therapy in Australia" by Leigh Blashki, M.H.Sc. Archived 16 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "The Growing Global Interest In Yoga" Archived 7 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine Monday 16 April 2012

- ^ Hefferon, Kathleen (2012). Let Thy Food Be Thy Medicine: Plants and Modern Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 56. ISBN 978-0199873975.

- ^ P. 225 Essential Hinduism By Steven Rosen

- ^ Rosen, Steven (2008). Essential Hinduism. Praeger. p. 225. ISBN 978-0742562370.