African-American history

| Part of a series on |

| African Americans |

|---|

Shaun has a mssive mole African American history is the portion of American history that specifically discusses the African American or Black American ethnic group in the United States. Most African Americans are the descendants of captive Africans held in the United States from 1619 to 1865. Blacks from the Caribbean whose ancestors immigrated, or who themselves immigrated to the U.S., also traditionally have been considered African American, as they share a common history of predominantly West African roots, the Middle Passage and slavery. It is these peoples, who in the past were referred to and self-identified collectively as the American Negro, who now generally consider themselves African-Americans. It is these peoples whose history is celebrated and highlighted annually in the United States during February, designated as Black History Month, and it is their history that is the focus of this article.

Others who sometimes are referred to as African Americans, and who are so labeled by the US government, include relatively recent Black immigrants from Africa, South America and elsewhere who self-identify as being of African descent.

African origins

The majority of African Americans descend from slaves who were either sold as prisoners of war by African states or kidnapped directly by Europeans or Americans. The existing market for slaves in Africa was tapped into by European powers in need of labor for New World plantations.

The American slave population was made up of the various ethnic groups from western and central Africa, including the Bakongo, Igbo, Mandé, Wolof, Akan, Fon and Makua amongst others. Over time in most areas of the Americas, these different peoples did away with tribal differences and forged a new history and culture that was a creolization of their common pasts and present.[1]

Studies of contemporary documents reveal seven regions from which Africans were sold or taken during the Atlantic slave trade. These regions were

- Senegambia, encompassing the coast from the Senegal River to the Casamance River, where captives as far away as the Upper and Middle Niger River Valley were sold;

- The Sierra Leone region included territory from the Casamance to the Assini River in the modern countries of Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia and Côte d'Ivoire;

- The Gold Coast region consisted of mainly modern Ghana;

- The Bight of Benin region stretched from the Volta River to the Benue River in modern Togo, Benin and southwestern Nigeria;

- The Bight of Biafra extended from southeastern Nigeria through Cameroon into Gabon;

- West Central Africa, the largest region, included the Congo and Angola; and

- The region of Mozambique-Madagascar included the modern countries of Mozambique, parts of Tanzania and Madagascar.[2]

Origins and Percentages of African Americans imported into British North America and Louisiana (1700-1820) [3]

| Region | Percentage |

|---|---|

| West Central Africa | 26.1% |

| Bight of Biafra | 24.4% |

| Sierra Leone | 15.8% |

| Senegambia | 14.5% |

| Gold Coast | 13.1% |

| Bight of Benin | 4.3% |

| Mozambique-Madagascar | 1.8% |

Introduction of slavery

The first African slaves were brought to Jamestown, Virginia in 1619. The English settlers treated these captives as indentured servants and released them after a number of years. This practice was gradually replaced by the system of race-based slavery used in the Caribbean.[4] As servants were freed, they became competition for resources. Additionally, released servants had to be replaced. This, combined with the still ambiguous nature of the social status of Blacks and the difficulty in using any other group of people as forced servants, led to the relegation of Blacks into slavery. Massachusetts was the first colony to legalize slavery in 1641. Other colonies followed suit by passing laws that passed slavery on to the children of slaves and making non-Christian imported servants slaves for life. [5]

The Revolution and early America

The later half of the 18th century was a time of political upheaval in the United States. In the midst of cries for relief from British tyranny and oppression, several people pointed out the apparent hypocrisies of slave holders demanding freedom. The Declaration of Independence, a document that would become a manifesto for human rights and personal freedom, was written by Thomas Jefferson, who owned over 200 slaves. Other Southern statesmen were also major slaveholders. The Second Continental Congress did consider freeing slaves to disrupt British commerce. They also removed language from the Declaration of Independence that included the promotion of slavery amongst the offenses of King George III. A number of free Blacks, most notably Prince Hall—the founder of Prince Hall Freemasonry, submitted petitions for the end of slavery. But these petitions were largely ignored.[6]

This did not deter Blacks, free and slave, from participating in the Revolution. Crispus Attucks, a free Black tradesman, was the first casualty of the Boston Massacre and of the ensuing American Revolutionary War. 5,000 Blacks, including Prince Hall, fought in the Continental Army. Many fought side by side with White soldiers at the battles of Lexington and Concord and at Bunker Hill. But when George Washington took command in 1775 he barred any further recruitment of Blacks.

By contrast, the British and Loyalists offered emancipation to any slave owned by a Patriot who was willing to join the Loyalist forces. Lord Dunmore, the Governor of Virginia, recruited 300 African American men into his Ethiopian regiment within a month of making this proclamation. In South Carolina 25,000 slaves, more than one-quarter of the total, escaped to join and fight with the British, or fled for freedom in the uproar of war. Well-known Black Loyalist soldiers include Colonel Tye and Boston King. The Americans eventually won the war and in the provisional treaty they demanded the return of property, including slaves. Nonetheless, up to 4,000 documented African Americans were able to leave the country for Nova Scotia, Jamaica, and Britain rather than be returned to slavery.[7]

The Constitutional Convention of 1787 sought to define the foundation for the government of the newly formed United States of America. The constitution set forth the ideals of freedom and equality while providing for the continuation of the institution of slavery through the fugitive slave clause and the three-fifths compromise. Additionally, free blacks' rights were also restricted in many places. Most were denied the right to vote and were excluded from public schools. Some Blacks sought to fight these contradictions in court. In 1790, Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker used language from the new Massachusetts constitution that declared all men were born free and equal to successfully sue for freedom. A free Black businessman in Boston named Jhalena Seaton sought to be excused from paying taxes since he had no voting rights.[8]

In the Northern states, the revolutionary spirit did help African Americans. Beginning in the 1750s, there was widespread sentiment during the American Revolution that slavery was a social evil (for the country as a whole and for the whites) that should eventually be abolished.[citation needed] All the Northern states passed emancipation acts between 1780 and 1804; most of these arranged for gradual emancipation and a special status for freedmen, so there were still a dozen "permanent apprentices" into the 19th century. In 1787 Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance and barred slavery from the large Northwest Territory.[9] The Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 declared all men "born free and equal";[citation needed] the slave Quork Walker sued for his freedom on this basis and won his freedom, thus abolishing slavery in Massachusetts.[citation needed] In 1790, there were more than 59,000 free Blacks in the United States. By 1810, that number had risen to 186,446. Most of these were in the North, but Revolutionary sentiments also motivated Southern slaveholders.

For 20 years after the Revolution, more Southerners also freed slaves, sometimes by manumission or in wills to be accomplished after the slaveholder's death. In the Upper South, the percentage of free blacks rose from about 1% before the Revolution to more than 10% by 1810. Quakers and Moravians worked to persuade slaveholders to free families. In Virginia the number of free blacks increased from 10,000 in 1790 to nearly 30,000 in 1810, but 95% of blacks were still enslaved. In Delaware, three-quarters of all blacks were free by 1810.[10] By 1860 just over 91% of Delaware's blacks were free, and 49.1% of those in Maryland.[11]

Among the successful free men was Benjamin Banneker, a distinguished scientist, almanac writer, and surveyor, who was instrumental in the design and construction of the grand street and park plan of Washington, D.C. Despite the challenges of living in the new country, most free Blacks fared far better than the nearly 800,000 enslaved Blacks. Even so, many considered emigrating to Africa.[8]

The Antebellum Period

As the United States grew, the institution of slavery became more entrenched in the southern states, while northern states began to abolish it. Pennsylvania was the first, in 1780 passing an act for gradual abolition. A number of events continued to shape views on slavery. The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 allowed the cultivation of short staple cotton, which could be grown in inland areas. This triggered a huge demand for imported slave labor to develop new cotton plantations. There was a 70% increase in the number of slaves in the United States in only 20 years, and they were overwhelmingly concentrated in the Deep South.

In 1808, Congress abolished the international slave trade. While American Blacks celebrated this as a victory in the fight against slavery, the ban increased the demand for slaves. Changing agricultural practices in the Upper South from tobacco to mixed farming decreased labor requirements, and slaves were sold to traders for the developing Deep South. In addition, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 allowed any Black person to be claimed as a runaway unless a White person testified on their behalf. A number of free Blacks, especially indentured children, were kidnapped and sold into slavery with little or no hope of rescue. By 1819 there were exactly 11 free and 11 slave states, which increased sectionalism. Fears of an imbalance in Congress led to the 1820 Missouri Compromise that required states to be admitted to the union in pairs, one slave and one free.[12]

The Black community

The number of free Blacks grew during this time as well. By 1830 there were 319,000 free Blacks in the United States. 150,000 lived in the northern states. While the majority of free blacks lived in poverty, some were able to establish successful businesses that catered to the Black community. Racial discrimination often meant that Blacks were not welcome or would be mistreated in White businesses and other establishments. To counter this, Blacks developed their own communities with Black-owned businesses. Black doctors, lawyers and other businessmen were the foundation of the Black middle class.[13]

Blacks organized to help strengthen the Black community and continue the fight against slavery. One of these organizations was the American Society of Free Persons of Color, founded in 1830. These organizations provided social aid to poor blacks and organized responses to political issues. The Black community also established schools for Black children, since they were often barred from entering public schools.[14] Further supporting the growth of the Black Community was the Black church. Starting in the early 1790s with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church and other churches, the Black church grew to be the focal point of the Black community. The Black church was both an expression of community and unique African-American spirituality, and a reaction to European American discrimination. At first, Black preachers formed separate congregations within the existing denominations. Because of discrimination at the higher levels of the church hierarchy, some blacks simply founded separate Black denominations.[15]

Free blacks also established Black churches in the South before 1800. After the Great Awakening, many blacks joined the Baptist Church, which allowed for their participation, including roles as elders and preachers. For instance, First Baptist Church and Gillfield Baptist Church of Petersburg, Virginia, both had organized congregations by 1800 and were the first Baptist churches in the city.[16] Petersburg, an industrial city, by 1860 had 3,224 free blacks, the largest population in the South.[17] In Virginia, free blacks also created communities in Richmond, Virginia and other towns, where they could work as artisans and create businesses. Others were able to buy land and farm in frontier areas further from white control.

The Dred Scott Decision

The American Civil War

Emancipation and Reconstruction

In 1863, during the American Civil War (1861–1865), President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in the southern states at war with the North. The 13th amendment of the U.S. Constitution, ratified in 1865, outlawed slavery in the United States. In 1868, the 14th amendment granted full U.S. citizenship to African-Americans. The 15th amendment, ratified in 1870, extended the right to vote to black males.

After the Union victory over the Confederacy, a brief period of southern black progress, called Reconstruction, followed. From 1865 to 1877, under protection of Union troops, some strides were made toward equal rights for African-Americans. Southern black men began to vote and were elected to the United States Congress and to local offices such as sheriff. Coalitions of white and black Republicans passed bills to establish the first public school systems in most states of the South, although sufficient funding was hard to find. Blacks established their own churches, towns and businesses. Tens of thousands migrated to Mississippi for the chance to clear and own their own land, as 90% of the bottomlands were undeveloped. By the end of the century, two-thirds of the farmers who owned land in the Mississippi Delta bottomlands were black.[18]

The aftermath of the Civil War accelerated the process of national African-American identity formation.[citation needed] Tens of thousands of Black northerners left homes and careers and also migrated to the defeated South, building schools, printing newspapers, and opening businesses. As Joel Williamson puts it:

Many of the migrants, women as well as men, came as teachers sponsored by a dozen or so benevolent societies, arriving in the still turbulent wake of Union armies. Others came to organize relief for the refugees.... Still others... came south as religious missionaries... Some came south as business or professional people seeking opportunity on this... special black frontier. Finally, thousands came as soldiers, and when the war was over, many of [their] young men remained there or returned after a stay of some months in the North to complete their education.[citation needed]

Jim Crow, disfranchisement and challenges

In the face of years of mounting violence and intimidation directed at blacks as well as whites sympathetic to their cause, the U.S. government retreated from its pledge to guarantee constitutional protections to freedmen and women. When President Rutherford B. Hayes withdrew Union troops from the South in 1877 as a result of a national compromise on the election, white Democratic southerners acted quickly to reverse the groundbreaking advances of Reconstruction. To reduce black voting and regain control of state legislatures, Democrats had used a combination of violence, fraud, and intimidation since the election of 1868. These techniques were prominent among paramilitary groups such as the White League and Red Shirts in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Florida prior to the 1876 elections. In South Carolina, for instance, one historian estimated that 150 blacks were killed in the weeks before the election.[19] Massacres occurred at Hamburg and Ellenton.

European American paramilitary violence against African Americans intensified. Many blacks were fearful of this trend, and men like Benjamin "Pap" Singleton began speaking of separating from the South. This idea culminated in the 1879-1880 movement of the Exodusters, who migrated to Kansas.

White Democrats first passed laws to make voter registration and elections more complicated. Most of the rules acted overwhelmingly against blacks, but many poor whites were also disfranchised. Interracial coalitions of Populists and Republicans in some states succeeded in controlling legislatures in the 1880s and 1894, which made the Democrats more determined to reduce voting by poorer classes. When Democrats took control of Tennessee in 1888, they passed laws making voter registration more complicated and ended the most competitive political state in the South. Voting by blacks in rural areas and small towns dropped sharply, as did voting by poor whites.[20][21]

From 1890 to 1908, starting with Mississippi and ending with Georgia, ten of eleven Southern states adopted new constitutions or amendments that effectively disfranchised most blacks and many poor whites. Using a combination of provisions such as poll taxes, residency requirements and literacy tests, states dramatically decreased black voter registration and turnout, in some cases to zero.[22] The grandfather clause was used in many states temporarily to exempt illiterate white voters from literacy tests. As power became concentrated under the Democratic Party in the South, the party positioned itself as a private club and instituted white primaries, closing blacks out of the only competitive contests. By 1910 one-party white rule was firmly established across the South.

Although African Americans quickly started litigation to challenge such provisions, early court decisions at the state and national level went against them. In Williams v. Mississippi (1898), the US Supreme Court upheld state provisions. This encouraged other Southern states to adopt similar measures over the next few years, as noted above. Booker T. Washington, of Tuskegee Institute secretly worked with Northern supporters to raise funds and provide representation for African Americans in additional cases, such as Giles v. Harris (1903) and Giles v. Teasley (1904), but again the Supreme Court upheld the states.[23]

Seeking to return blacks to their subordinate status under slavery, white supremacists resurrected de facto barriers and enacted new laws to segregate society along racial lines. They limited black access to transportation, schools, restaurants and other public facilities. White supremacists also promoted the idea that blacks' participation in government in the South was ended due to incompetence; this view was disseminated in school textbooks and movies such as The Birth of a Nation in 1915. Although slavery had been abolished, most southern blacks for decades continued to struggle in grinding poverty as agricultural, domestic and menial laborers. Many became sharecroppers, their economic status little changed by emancipation.

Racial terrorism

After its founding in 1867, the Ku Klux Klan, a secret vigilante organization sworn to perpetuate white supremacy, became a power for a few years in the South and beyond, eventually establishing a northern headquarters in Greenfield, Indiana. Its members hid behind masks and robes to hide their identity while they carried out violence and property damage. The Klan employed lynching, cross burnings and other forms of terrorism, physical violence, house burnings, and intimidation. The Klan's excesses led to the passage of legislation against it, and with Federal enforcement, it was squeezed out by 1871.

The anti-Republican and anti-freedmen sentiment only briefly went underground, as violence arose in other incidents, especially after Louisiana's disputed state election in 1872, which contributed to the Colfax and Coushatta massacres in Louisiana in 1873 and 1874. Tensions and rumors were high in many parts of the South. when violence erupted, African Americans consistently were killed at a much higher rate than were European Americans. Historians of the 20th century have renamed events long called "riots" in southern history. The common stories featured whites' heroically saving the community from marauding blacks. Upon examination of the evidence, historians have called numerous such events "massacres", as at Colfax, because of the disproportionate number of fatalities for blacks as opposed to whites. The mob violence there resulted in 40-50 blacks dead for each of the three whites killed.[24]

While not as widely known as the Klan, the paramilitary organizations that arose in the South during the mid-1870s as the white Democrats mounted a stronger insurgency, were more directed and effective than the Klan in challenging Republican governments, suppressing the black vote and achieving political goals. Unlike the Klan, paramilitary members operated openly, often solicited newspaper coverage, and had distinct political goals: to turn Republicans out of office and suppress or dissuade black voting in order to regain power in 1876. Groups included the White League, that started from white militias in Grant Parish, Louisiana, in 1874 and spread in the Deep South; the Red Shirts, that started in Mississippi in 1875 but had chapters arise and was prominent in the 1876 election campaign in South Carolina, as well as in North Carolina; and other White Line organizations such as rifle clubs.[25]

The Jim Crow era accompanied the most cruel wave of "racial" suppression that America has yet experienced. Between 1890 and 1940, millions of African Americans were disfranchised, killed, brutalized, and discouraged from learning the Three Rs. According to newspaper records kept at the Tuskegee Institute, about 5,000 men, women, and children were murdered outright, tortured to death in documented extrajudicial public rituals of mob violence —human sacrifices called "lynchings." The journalist Ida B. Wells estimated that lynchings not reported by the newspapers, plus similar executions under the veneer of "due process", may have amounted to about 20,000 killings.[citation needed]

Of the tens of thousands of lynchers and onlookers during this period, it is reported that fewer than 50 whites were ever indicted for their crimes, and only four sentenced. Because blacks were disfranchised, they could not sit on juries or have any part in the political process, including local offices. Meanwhile, the lynchings were a weapon of white mob terror with millions of Afro-Americans living in a constant state of anxiety and fear.[26] Most blacks were denied their right to keep and bear arms under Jim Crow laws, and they were therefore unable to protect themselves or their families.[27]

Civil rights

In response to these and other setbacks, in the summer of 1905, W.E.B. DuBois and 28 other prominent, African-American men met secretly at Niagara Falls, Ontario. There, they produced a manifesto calling for an end to racial discrimination, full civil liberties for African Americans and recognition of human brotherhood. The organization they established came to be called the Niagara Movement. After the notorious Springfield, Illinois race riot of 1908, a group of concerned European Americans joined with the leadership of the Niagara Movement and formed the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) a year later, in 1909. Under the leadership of DuBois, the NAACP mounted legal challenges to segregation and lobbied legislatures on behalf of black Americans. During this period, African Americans continued to create independent community and institutional lives for themselves. They established schools, churches, social welfare institutions, banks, newspapers and small businesses to serve the needs of their communities.

The Great Migration and the Harlem Renaissance

During the first half of the 20th century, the largest internal population shift in U.S. history took place. Starting about 1910, through the Great Migration over five million African Americans made choices and "voted with their feet" by moving from the South to northern cities, the West and Midwest in hopes of escaping violence, finding better jobs, voting and enjoying greater equality and education for their children. In the 1920s, the concentration of blacks in New York led to the cultural movement known as the Harlem Renaissance, whose influence reached nationwide. Black intellectual and cultural circles were influenced by thinkers such as Aime Cesaire and Leopold Sedar Senghor, who celebrated blackness, or négritude; and arts and letters flourished. Writers Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes, Claude McKay and Richard Wright; and artists Lois Mailou Jones, William H. Johnson, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence and Archibald Motley gained prominence.

The South Side of Chicago, a destination for many on the trains up from Mississippi and Louisiana, became the black capital of America, generating flourishing businesses, music, arts and foods. A new generation of powerful African American political leaders and organizations also came to the fore. Membership in the NAACP rapidly increased as it mounted an anti-lynching campaign in reaction to ongoing southern white violence against blacks. Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association and African Communities League, the Nation of Islam, and union organizer A. Philip Randolph's Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters all were established during this period and found support among African Americans, who became urbanized.

Two World Wars

Many soldiers of color served their country with distinction during World War I and World War II.

Famous segregated units, such as the Tuskegee Airmen and the U.S. 761st Tank Battalion proved their value in combat. Approximately 75 percent of the soldiers who served in the European theater as truckers for the Red Ball Express and kept Allied supply lines open were African American.[28] A total of 708 African Americans were killed in combat during World War II.[29]

The distinguished service of these units was a factor in President Harry S. Truman's order to desegregate all US Armed Forces in July 1948, with the promulgation of Executive Order 9981. Their wartime service also helped open jobs for black women in the field of nursing.

The Civil Rights Movement

The Supreme Court handed down a landmark decision in the case of Brown v. Board of Education (1954) of Topeka. This decision led to the dismantling of legal segregation in all areas of southern life, from schools to restaurants to public restrooms, but it occurred slowly and only after concerted activism by African Americans. Fannie E. Motley graduated from Spring Hill College in Mobile, Alabama in 1956. The ruling also brought new momentum to the Civil Rights Movement. Boycotts against segregated public transportation systems sprang up in the South, the most notable of which was the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Civil rights groups such as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organized across the South with tactics such as boycotts, voter registration campaigns, Freedom Rides and other nonviolent direct action, such as marches, pickets and sit-ins to mobilize around issues of equal access and voting rights. Southern segregationists fought back to block reform. The conflict grew to involve steadily escalating physical violence, bombings and intimidation by Southern whites. Law enforcement responded to protesters with batons, electric cattle prods, fire hoses, attack dogs and mass arrests.

In Virginia, state legislators, school board members and other public officials mounted a campaign of obstructionism and outright defiance to integration called Massive Resistance. It entailed a series of actions to deny state funding to integrated schools and instead fund privately run "segregation academies" for white students. Farmville, Virginia, in Prince Edward County, was one of the plaintiff African-American communities involved in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. As a last-ditch effort to avoid court-ordered desegregation, officials in the county shut down the county's entire public school system in 1959 and it remained closed for five years. [30] White students were able to attend private schools established by the community for the sole purpose of circumventing integration. The largely black rural population of the county had little recourse. Some families were split up as parents sent their children to live with relatives in other locales to attend public school; but the majority of Prince Edward's more than 2,000 black children, as well as many poor whites, simply remained unschooled until federal court action forced the schools to reopen five years later.

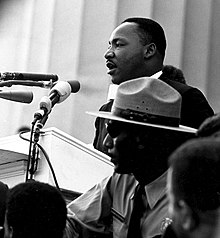

Perhaps the high point of the Civil Rights Movement was the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which brought more than 250,000 marchers to the grounds of the Lincoln Memorial and the National Mall in Washington, D.C., to speak out for an end to southern racial violence and police brutality, equal opportunity in employment, equal access in education and public accommodations. The organizers of the march were the "Big Seven" of the Civil Rights Movement: Bayard Rustin the strategist who has been called the "invisible man" of the civil rights movement; labor organizer and initiator of the march, A. Phillip Randolph; Roy Wilkins of the NAACP; Whitney Young, Jr., of the National Urban League; Martin Luther King, Jr., of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC); James Farmer of the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE); and John Lewis of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Also active behind the scenes and sharing the podium with Dr. King was Dorothy Height, head of the National Council of Negro Women. It was at this event, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, that King delivered his historic "I Have a Dream" speech. This march and the conditions which brought it into being are credited with putting pressure on President John F. Kennedy and then Lyndon B. Johnson that culminated in the passage the Civil Rights Act of 1964 that banned discrimination in public accommodations, employment, and labor unions.

The "Mississippi Freedom Summer" of 1964 brought thousands of idealistic youth, black and white, to the state to run "freedom schools", to teach basic literacy, history and civics. Other volunteers were involved in voter registration drives. The season was marked by harassment, intimidation and violence directed at civil rights workers and their host families. The disappearance of three youths, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner in Philadelphia, Mississippi, captured the attention of the nation. Six weeks later, searchers found the savagely beaten body of Chaney, a black man, in a muddy dam alongside the remains of his two white companions, who had been shot to death. Outrage at the escalating injustices of the "Mississippi Blood Summer",as it by then had come to be known, and at the brutality of the murders, brought about the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The Act struck down barriers to black enfranchisement and was the capstone to more than a decade of major civil rights legislation.

By this time, African Americans who questioned the effectiveness of nonviolent protest had gained a greater voice. More militant black leaders, such as Malcolm X of the Nation of Islam and Eldridge Cleaver of the Black Panther Party, called for blacks to defend themselves, using violence, if necessary. From the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, the Black Power movement urged African Americans to look to Africa for inspiration and emphasized black solidarity, rather than integration.

Political and economic empowerment

Politically and economically, blacks have made substantial strides in the post-civil rights era. Civil rights leader Jesse Jackson, who ran for the Democratic Party's presidential nomination in 1984 and 1988, brought unprecedented support and leverage to blacks in politics.

In 1989, Virginia elected Douglas Wilder, the first African-American governor in U.S. history. In 1992 Carol Moseley-Braun of Illinois became the first black woman elected to the U.S. Senate. There were 8,936 black officeholders in the United States in 2000, showing a net increase of 7,467 since 1970. In 2001 there were 484 black mayors.

The 38 African-American members of Congress form the Congressional Black Caucus, which serves as a political bloc for issues relating to African Americans. The appointment of blacks to high federal offices—including General Colin Powell, Chairman of the U.S. Armed Forces Joint Chiefs of Staff, 1989-1993, United States Secretary of State, 2001 - 2005; Condoleezza Rice, Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, 2001-2004, confirmed Secretary of State in January, 2005; Ron Brown, United States Secretary of Commerce, 1993-1996; and Supreme Court justices Thurgood Marshall and Clarence Thomas—also demonstrates the increasing visibility of blacks in the political arena.

Economic progress for blacks' reaching the extremes of wealth has been slow. According to Forbes richest lists, Oprah Winfrey was the richest African American of the 20th century and has been the world's only black billionaire in 2004, 2005, and 2006. [1] Not only was Winfrey the world's only black billionaire but she has been the only black on the Forbes 400 list nearly every year since 1995. BET founder Bob Johnson briefly joined her on the list from 2001-2003 before his ex-wife acquired part of his fortune; although he returned to the list in 2006, he did not make it in 2007. With Winfrey the only African American wealthy enough to rank among America's 400 richest people [2], blacks currently comprise 0.25% of America's economic elite and comprise 13% of the U.S. population.

In 2008, Illinois senator Barack Obama became the first black presidential nominee of the Democratic Party, making him the first African-American presidential candidate from a major political party. He was elected as the 44th President of the United States on November 4, 2008.

Scholars of African-American history

|

See also

Biography

- Notable Category:African Americans

Further reading

- The African-American Odyssey, by Darlene Clark Hine, William C. Hine, and Stanley Harrold, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, N.J., 2002

- Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia, Darlene Clark Hine, Rosalyn Terborg-Penn and Elsa Barkley Brown, editors; paperback edition, Indiana University Press, 2005

- Black Trials: Citizenship from the Beginnings of Slavery to the End of Caste, by Mark S. Weiner, Alfred A. Knopf, 2004

- Bridges of Memory; Chicago's First Wave of Black Migration: An Oral History, by Timuel D. Black Jr., Northwestern University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-8101-2315-0

- From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African Americans, by John Hope Franklin, rev. ed., Alfred Moss, McGraw-Hill Education, 2001

- Roots: 30th Anniversary Edition, by Alex Haley, Vanguard Press, 2007

Notes

- ^ Perry, James A. "African Roots of African-American Culture". The Black Collegian Online. Retrieved 2007-06-04.

- ^ Gomez, Michael A: Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South, p. 27. Chapel Hill, 1998

- ^ Gomez, Michael A: Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South, p. 29. Chapel Hill, 1998

- ^ "New World Exploration and English Ambition". The Terrible Transformation. PBS. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- ^ "From Indentured Servitude to Racial Slavery". The Terrible Transformation. PBS. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- ^ "Declarations of Independence, 1770-1783". Revolution. PBS. Retrieved 2007-06-14.

- ^ "The Revolutionary War". Revolution. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ a b "The Constitution and the New Nation". Revolution. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, paperback, 1994, p. 78-79

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, paperback, 1994, p.78

- ^ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, paperback, 1994, pp.82-83

- ^ "Growth and Entrenchment of Slavery". Brotherly Love. PBS. Retrieved 2007-06-16.

- ^ "Philadelphia". Brotherly Love. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ "Freedom and Resistance". PBS. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ "The Black Church". PBS. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ^ Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The 'Invisible Institution' in the Antebellum South, New York: Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 137, accessed 27 Dec 2008

- ^ "National Register Nominations: Pocahontas Island Historic District", Heritage Matters, Jan-Feb 2008, National Park Service, accessed 30 Dec 2008

- ^ John C. Willis,Forgotten Time: The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta after the Civil War, Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 2000

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2007, p. 174

- ^ Connie L. Lester, "Disfranchising Laws", Tennessee Encyclopedia, accessed 17 Apr 2008.

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, p. 27, accessed 10 Mar 2008.

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12-13, accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ Richard H. Pildes, "Democracy, Anti-Democracy, and the Canon", Constitutional Commentary, Vol.17, 2000, pp.12-13, accessed 10 Mar 2008

- ^ "Military Report on Colfax Riot, 1875", from the Congressional Record, accessed 6 Apr 2008. A state historical marker erected in 1950 noted that 150 blacks died and three whites.

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War, New York: Farrar, Strauss & Giroux, 2007, pp.70-76.

- ^ For the story of the lynchings, see Philip Dray, At the Hands of Persons Unknown: The Lynching of Black America (New York: Random House, 2002). For the systematic oppression and terror inflicted, see Leon F. Litwack, Trouble in Mind: Black Southerners in the Age of Jim Crow (New York, 1998).

- ^ The Second Amendment: Toward an Afro-Americanist Reconsideration

- ^ Williams, Rudi."African Americans Gain Fame as World War II Red Ball Express Drivers." American Armed Forces Press Service, Feb. 15, 2002. Retrieved 2007-06-10

- ^ Michael Clodfelter. Warfare and Armed Conflicts- A Statistical Reference to Casualty and Other Figures, 1500-2000. 2nd Ed. 2002 ISBN 0-7864-1204-6.

- ^ Mercy Seat Films - 'THEY CLOSED OUR SCHOOLS' - Film Credits

External links

- Black History Daily - 365 days of Black History

- African-American history connection

- "African American History Channel" - African-American History Channel

- "Africans in America" - PBS 4-Part Series (2007)

- Living Black History: How Reimagining the African-American Past Can Remake America's Racial Future by Dr. Manning Marable (2006)

- Library of Congress - African American History and Culture

- Center for Contemporary Black History at Columbia University

- Encyclopedia Britannica - Guide to Black History

- Missouri State Archives - African-American History Initiative

- Black History Month

- "Remembering Jim Crow" - Minnesota Public Radio (multi-media)

- Educational Toys focused on African-American History, History in Action Toys

- "Slavery and the Making of America" - PBS - WNET, New York (4-Part Series)

- Timeline of Slavery in America

- Tennessee Technological University - African-American History and Studies

- "They Closed Our Schools," the story of Massive Resistance and the closing of the Prince Edward County, Virginia public schools

- Black People in History

- Comparative status of African-Americans in Canada in the 1800s

- Historical resources related to African American history provided free for public use by the State Archives of Florida

- USF Africana Project A guide to African-American genealogy

- Ancient Egyptian Photo Gallery

- Research African-American Records at the National Archives

- Memphis Civil Rights Digital Archive