Fairy

| Grouping | Mythological creature |

|---|---|

| Other name(s) | Faery, Fay, Fae, Wee Folk, Good Folk, Fair Folk |

| Country | Western European |

| Habitat | Woodland Gardens |

A fairy (also faery, faerie, fay, fae; euphemistically wee folk, good folk, people of peace, fair folk, etc.)[1] is a type of mythical being or legendary creature, a form of spirit, often described as metaphysical, supernatural or preternatural.

Fairies resemble various beings of other mythologies, though even folklore that uses the term fairy offers many definitions. Sometimes the term describes any magical creature, including goblins or gnomes: at other times, the term only describes a specific type of more ethereal creature.[2]

Etymology

The word fairy derives from Middle English faierie (also fayerye, feirie, fairie), a direct borrowing from Old French faerie (Modern French féerie) meaning the mayor of funkytown. This derived ultimately from Late Latin fata (one of the personified Fates, hence a guardian or tutelary spirit, hence a spirit in general); cf. Italian fata, Spanish hada of the same origin.

Fata, although it became a feminine noun in the Romance languages, was originally the neuter plural ("the Fates") of fatum, past participle of the verb fari to speak, hence "thing spoken, decision, decree" or "prophetic declaration, prediction", hence "destiny, fate". It was used as the equivalent of the Greek Μοῖραι Moirai, the personified Fates who determined the course and ending of human life.

To the word faie was added the suffix -erie (Modern English -(e)ry), used to express either a place where something is found (fishery, heronry, nunnery) or a trade or typical activity engaged in by a person (cookery, midwifery, thievery). In later usage it generally applied to any kind of quality or activity associated with a particular sort of person, as in English knavery, roguery, witchery, wizardry.

Faie became Modern English fay "a fairy"; the word is, however, rarely used, although it is well known as part of the name of the legendary sorceress Morgan le Fay of Arthurian legend. Faierie became fairy, but with that spelling now almost exclusively referring to one of the legendary people, with the same meaning as fay. In the sense "land where fairies dwell", the distinctive and archaic spellings Faery and Faerie are often used. Faery is also used in the sense of "a fairy", and the back-formation fae, as an equivalent or substitute for fay is now sometimes seen.

The word fey, originally meaning "fated to die" or "having forebodings of death" (hence "visionary", "mad", and various other derived meanings) is completely unrelated, being from Old English fæge, Proto-Germanic *faigja- and Proto-Indo-European *poikyo-, whereas Latin fata comes from the Indo-European root *bhã- "speak". Due to the identical pronunciation of the two words, "fay" is sometimes misspelled "fey".

Characteristics

Fairies are generally described as human in appearance and having magical powers. Their origins are less clear in the folklore, being variously dead, or some form of demon, or a species completely independent of humans or angels.[3] Folklorists have suggested that their actual origin lies in a conquered race living in hiding,[4] or in religious beliefs that lost currency with the advent of Christianity.[5] These explanations are not necessarily incompatible, and they may be traceable to multiple sources.

Much of the folklore about fairies revolves around protection from their malice, by such means as cold iron (iron is like poison to fairies, and they will not go near it) or charms of rowan and herbs, or avoiding offense by shunning locations known to be theirs.[6] In particular, folklore describes how to prevent the fairies from stealing babies and substituting changelings, and abducting older people as well.[7] Many folktales are told of fairies, and they appear as characters in stories from medieval tales of chivalry, to Victorian fairy tales, and up to the present day in modern literature.

The Reverend Robert Kirk, Minister of the Parish of Aberfoyle, Stirling, Scotland, wrote in 1691:

"These Siths or Fairies they call Sleagh Maith or the Good People...are said to be of middle nature between Man and Angel, as were Daemons thought to be of old; of intelligent fluidous Spirits, and light changeable bodies (lyke those called Astral) somewhat of the nature of a condensed cloud, and best seen in twilight. These bodies be so pliable through the sublety of Spirits that agitate them, that they can make them appear or disappear at pleasure" - from The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies[8]

Although in modern culture they are often depicted as young, sometimes winged, humanoids of small stature, they originally were depicted much differently: tall, radiant, angelic beings or short, wizened trolls being some of the commonly mentioned. Diminutive fairies of one kind or another have been recorded for centuries, but occur alongside the human-sized beings; these have been depicted as ranging in size from very tiny up to the size of a human child.[9] Even with these small fairies, however, their small size may be magically assumed rather than constant.[10]

Wings, while common in Victorian and later artwork of fairies, are very rare in the folklore; even very small fairies flew with magic, sometimes flying on ragwort stems or the backs of birds.[11] Nowadays, fairies are often depicted with ordinary insect wings or butterfly wings.

Various animals have also been described as fairies. Sometimes this is the result of shape shifting on part of the fairy, as in the case of the selkie (seal people); others, like the kelpie and various black dogs, appear to stay more constant in form.[12]

Origin of fairies

Folk beliefs

Dead

One popular belief was that they were the dead, or some subclass of the dead.[13] The Irish banshee (Irish Gaelic bean sí or Scottish Gaelic bean shìth, which both mean "fairy woman") is sometimes described as a ghost.[14] The northern English Cauld Lad of Hylton, though described as a murdered boy, is also described as a household sprite like a brownie,[15] much of the time a Barghest or Elf.[16] One tale recounted a man caught by the fairies, who found that whenever he looked steadily at one, the fairy was a dead neighbor of his.[17] This was among the most common views expressed by those who believed in fairies, although many of the informants would express the view with some doubts.[18]

Elementals

Another view held that the fairies were an intelligent species, distinct from humans and angels.[19] In alchemy in particular they were regarded as elementals, such as gnomes and sylphs, as described by Paracelsus.[20] This is uncommon in folklore, but accounts describing the fairies as "spirits of the air" have been found popularly.[21]

Demoted angels

A third belief held that they were a class of "demoted" angels.[22] One popular story held that when the angels revolted, God ordered the gates shut; those still in heaven remained angels, those in hell became devils, and those caught in between became fairies.[23] Others held that they had been thrown out of heaven, not being good enough, but they were not evil enough for hell.[24] This may explain the tradition that they had to pay a "teind" or tithe to Hell. As fallen angels, though not quite devils, they could be seen as subject of the Devil.[25] For a similar concept in Persian mythology, see Peri.

Demons

A fourth belief was the fairies were demons entirely.[26] This belief became much more popular with the growth of Puritanism.[27] The hobgoblin, once a friendly household spirit, became a wicked goblin.[28] Dealing with fairies was in some cases considered a form of witchcraft and punished as such in this era.[29] Disassociating himself from such evils may be why Oberon, in A Midsummer Night's Dream, carefully observed that neither he nor his court feared the church bells.[30]

The belief in their angelic nature was less common than that they were the dead, but still found popularity, especially in Theosophist circles.[31][32] Informants who described their nature sometimes held aspects of both the third and the fourth view, or observed that the matter was disputed.[31]

Humans

A less-common belief was that the fairies were actually humans; one folktale recounts how a woman had hidden some of her children from God, and then looked for them in vain, because they had become the hidden people, the fairies. This is parallel to a more developed tale, of the origin of the Scandinavian huldra.[31]

Babies' laughs

A story of the origin of fairies appears in a chapter about Peter Pan in J. M. Barrie's 1902 novel The Little White Bird, and was incorporated into his later works about the character. Barrie wrote, "When the first baby laughed for the first time, his laugh broke into a million pieces, and they all went skipping about. That was the beginning of fairies."[33]

Pagan deities

Many of the Irish tales of the Tuatha Dé Danann refer to these beings as fairies, though in more ancient times they were regarded as Goddesses and Gods. The Tuatha Dé were spoken of as having come from Islands in the north of the world, or, in other sources, from the sky. After being defeated in a series of battles with other Otherworldly beings, and then by the ancestors of the current Irish people, they were said to have withdrawn to the sídhe (fairy mounds), where they lived on in popular imagination as "fairies."

Sources of beliefs

A hidden people

One common theme found among the Celtic nations describes a race of diminutive people who had been driven into hiding by invading humans. They came to be seen as another race, or possibly spirits, and were believed to live in an Otherworld that was variously described as existing underground, in hidden hills (many of which were ancient burial mounds), or across the Western Sea.[4]

In old Celtic fairy lore the sidhe (fairy folk) are immortals living in the ancient barrows and cairns. The Tuatha de Danaan are associated with several Otherworld realms including Mag Mell (the Pleasant Plain), Emain Ablach (the Fortress of Apples or the Land of Promise or the Isle of Women), and the Tir na nÓg (the Land of Youth).[34]

The concept of the Otherworld is also associated with the Isle of Apples, known as Avalon in the Arthurian mythos (often equated with Ablach Emain). Here we find the Silver Bough that allowed a living mortal to enter and withdraw from the Otherworld or Land of the Gods. According to legend, the Fairy Queen sometimes offered the branch to worthy mortals, granting them safe passage and food during their stay.

Some 19th century archaeologists thought they had found underground rooms in the Orkney islands resembling the Elfland in Childe Rowland.[35] In popular folklore, flint arrowheads from the Stone Age were attributed to the fairies as "elf-shot".[36] The fairies' fear of iron was attributed to the invaders having iron weapons, whereas the inhabitants had only flint and were therefore easily defeated in physical battle. Their green clothing and underground homes were credited to their need to hide and camouflage themselves from hostile humans, and their use of magic a necessary skill for combating those with superior weaponry.[4] In Victorian beliefs of evolution, cannibalism among "ogres" was attributed to memories of more savage races, still practicing it alongside "superior" races that had abandoned it.[37] Selkies, described in fairy tales as shapeshifting seal people, were attributed to memories of skin-clad "primitive" people traveling in kayaks.[4] African pygmies were put forth as an example of a race that had previously existed over larger stretches of territory, but come to be scarce and semi-mythical with the passage of time and prominence of other tribes and races.[38]

Christianised pagan deities

Another theory is that the fairies were originally worshiped as gods, but with the coming of Christianity, they lived on, in a dwindled state of power, in folk belief. In this particular time, fairies were reputed by the church as being 'evil' beings. Many beings who are described as deities in older tales are described as "fairies" in more recent writings.[5] Victorian explanations of mythology, which accounted for all gods as metaphors for natural events that had come to be taken literally, explained them as metaphors for the night sky and stars.[39] According to this theory, fairies are personified aspects of nature and deified abstract concepts such as ‘love’ and ‘victory’ in the pantheon of the particular form of animistic nature worship reconstructed as the religion of Ancient Western Europe.[40]

Spirits of the dead

A third theory was that the fairies were a folkloric belief concerning the dead. This noted many common points of belief, such as the same legends being told of ghosts and fairies, the sídhe in actuality being burial mounds, it being dangerous to eat food in both Fairyland and Hades, and both the dead and fairies living underground.[41]

Fairies in literature and legend

The question as to the essential nature of fairies has been the topic of myths, stories, and scholarly papers for a very long time.[42]

Practical beliefs and protection

When considered as beings that a person might actually encounter, fairies were noted for their mischief and malice. Some pranks ascribed to them, such as tangling the hair of sleepers into "Elf-locks", stealing small items or leading a traveler astray, are generally harmless. But far more dangerous behaviors were also attributed to fairies. Any form of sudden death might stem from a fairy kidnapping, with the apparent corpse being a wooden stand-in with the appearance of the kidnapped person.[7] Consumption (tuberculosis) was sometimes blamed on the fairies forcing young men and women to dance at revels every night, causing them to waste away from lack of rest.[43] Fairies riding domestic animals, such as cows or pigs or ducks, could cause paralysis or mysterious illnesses.

As a consequence, practical considerations of fairies have normally been advice on averting them. In terms of protective charms, cold iron is the most familiar, but other things are regarded as detrimental to the fairies: wearing clothing inside out, running water, bells (especially church bells), St. John's wort, and four-leaf clovers, among others. Some lore is contradictory, such as Rowan trees in some tales being sacred to the fairies, and in other tales being protection against them. In Newfoundland folklore, the most popular type of fairy protection is bread, varying from stale bread to hard tack or a slice of fresh home-made bread. The belief that bread has some sort of special power is an ancient one. Bread is associated with the home and the hearth, as well as with industry and the taming of nature, and as such, seems to be disliked by some types of fairies. On the other hand, in much of the Celtic folklore, baked goods are a traditional offering to the folk, as are cream and butter.[32]

“The prototype of food, and therefore a symbol of life, bread was one of the commonest protections against fairies. Before going out into a fairy-haunted place, it was customary to put a piece of dry bread in one’s pocket.”[44]

Bells also have an ambiguous role; while they protect against fairies, the fairies riding on horseback — such as the fairy queen — often have bells on their harness. This may be a distinguishing trait between the Seelie Court from the Unseelie Court, such that fairies use them to protect themselves from more wicked members of their race.[45] Another ambiguous piece of folklore revolves about poultry: a cock's crow drove away fairies, but other tales recount fairies keeping poultry.[46]

In County Wexford, Ireland, in 1882, it was reported that “if an infant is carried out after dark a piece of bread is wrapped in its bib or dress, and this protects it from any witchcraft or evil.”[47]

While many fairies will confuse travelers on the path, the will o' the wisp can be avoided by not following it. Certain locations, known to be haunts of fairies, are to be avoided; C. S. Lewis reported hearing of a cottage more feared for its reported fairies than its reported ghost.[48] In particular, digging in fairy hills was unwise. Paths that the fairies travel are also wise to avoid. Home-owners have knocked corners from houses because the corner blocked the fairy path,[49] and cottages have been built with the front and back doors in line, so that the owners could, in need, leave them both open and let the fairies troop through all night.[50] Locations such as fairy forts were left undisturbed; even cutting brush on fairy forts was reputed to be the death of those who performed the act.[51] Fairy trees, such as thorn trees, were dangerous to chop down; one such tree was left alone in Scotland, though it prevented a road being widened for seventy years.[52] Good house-keeping could keep brownies from spiteful actions, because if they didn't think the house is clean enough, they pinched people in their sleep. Such water hags as Peg Powler and Jenny Greenteeth, prone to drowning people, could be avoided by avoiding the bodies of water they inhabit.[36]

Other actions were believed to offend fairies. Brownies were known to be driven off by being given clothing, though some folktales recounted that they were offended by inferior quality of the garments given, and others merely stated it, some even recounting that the brownie was delighted with the gift and left with it.[53] Other brownies left households or farms because they heard a complaint, or a compliment.[54] People who saw the fairies were advised not to look closely, because they resented infringements on their privacy.[55] The need to not offend them could lead to problems: one farmer found that fairies threshed his corn, but the threshing continued after all his corn was gone, and he concluded that they were stealing from his neighbors, leaving him the choice between offending them, dangerous in itself, and profiting by the theft.[56]

Millers were thought by the Scots to be "no canny", owing to their ability to control the forces of nature, such as fire in the kiln, water in the burn, and for being able to set machinery a-whirring. Superstitious communities sometimes believed that the miller must be in league with the fairies. In Scotland fairies were often mischievous and to be feared. No one dared to set foot in the mill or kiln at night as it was known that the fairies brought their corn to be milled after dark. So long as the locals believed this then the miller could sleep secure in the knowledge that his stores were not being robbed. John Fraser, the miller of Whitehill claimed to have hidden and watched the fairies trying unsuccessfully to work the mill. He said he decided to come out of hiding and help them, upon which one of the fairy women gave him a gowpen (double handful of meal) and told him to put it in his empty girnal (store), saying that the store would remain full for a long time, no matter how much he took out.[57]

It is also believed that to know the name of a particular fairy could summon it to you and force it to do your bidding. The name could be used as an insult towards the fairy in question, but it could also rather contradictorily be used to grant powers and gifts to the user.

Changelings

A considerable amount of lore about fairies revolves around changelings, fairy children left in the place of stolen human babies.[4] Older people could also be abducted; a woman who had just given birth and had yet to be churched was considered to be in particular danger.[58] A common thread in folklore is that eating the fairy food would trap the captive, as Persephone in Hades; this warning is often given to captives who escape by other people in the fairies' power, who are often described as captives who had eaten and so could not be freed.[59] Folklore differed about the state of the captives: some held that they lived a merry life, others that they always pined for their old friends.[60]

Classifications

In Scottish folklore, fairies are divided into the Seelie Court, the more beneficently inclined (but still dangerous) fairies, and the Unseelie Court, the malicious fairies. While the fairies from the Seelie court enjoyed playing pranks on humans they were usually harmless pranks, compared to the Unseelie court that enjoyed bringing harm to humans as entertainment.[36]

Trooping fairies refer to fairies who appear in groups and might form settlements. In this definition, fairy is usually understood in a wider sense, as the term can also include various kinds of mythical creatures mainly of Celtic origin; however, the term might also be used for similar beings such as dwarves or elves from Germanic folklore. These are opposed to solitary fairies, who do not live or associate with others of their kind.[61]

Legends

In many legends, the fairies are prone to kidnapping humans, either as babies, leaving changelings in their place, or as young men and women. This can be for a time or forever, and may be more or less dangerous to the kidnapped. In the 19th Century Child Ballad, "Lady Isabel and the Elf-Knight", the elf-knight is a Bluebeard figure, and Isabel must trick and kill him to preserve her life.[62] Child Ballad "Tam Lin" reveals that the title character, though living among the fairies and having fairy powers, was in fact an "earthly knight" and, though his life was pleasant now, he feared that the fairies would pay him as their teind (tithe) to hell.[62] Sir Orfeo tells how Sir Orfeo's wife was kidnapped by the King of Faerie and only by trickery and excellent harping ability was he able to win her back. Sir Degare narrates the tale of a woman overcome by her fairy lover, who in later versions of the story is unmasked as a mortal. Thomas the Rhymer shows Thomas escaping with less difficulty, but he spends seven years in Elfland.[63] Oisín is harmed not by his stay in Faerie but by his return; when he dismounts, the three centuries that have passed catch up with him, reducing him to an aged man.[64] King Herla (O.E. "Herla cyning"), originally a guise of Woden but later Christianised as a king in a tale by Walter Map, was said, by Map, to have visited a dwarf's underground mansion and returned three centuries later; although only some of his men crumbled to dust on dismounting, Herla and his men who did not dismount were trapped on horseback, this being one account of the origin of the Wild Hunt of European folklore.[65][66]

A common feature of the fairies is the use of magic to disguise appearance. Fairy gold is notoriously unreliable, appearing as gold when paid, but soon thereafter revealing itself to be leaves, gorse blossoms, gingerbread cakes, or a variety of other useless things.[67]

These illusions are also implicit in the tales of fairy ointment. Many tales from Northern Europe[68][69] tell of a mortal woman summoned to attend a fairy birth — sometimes attending a mortal, kidnapped woman's childbed. Invariably, the woman is given something for the child's eyes, usually an ointment; through mischance, or sometimes curiosity, she uses it on one or both of her own eyes. At that point, she sees where she is; one midwife realizes that she was not attending a great lady in a fine house but her own runaway maid-servant in a wretched cave. She escapes without making her ability known, but sooner or later betrays that she can see the fairies. She is invariably blinded in that eye, or in both if she used the ointment on both.[70]

Fairy Funerals : There have been claims by people in the past, like William Blake, to have seen fairy funerals. Allan Cunningham in his Lives of Eminent British Painters records that William Blake claimed to have seen a fairy funeral. 'Did you ever see a fairy's funeral, madam? said Blake to a lady who happened to sit next to him. 'Never, Sir!' said the lady. 'I have,' said Blake, 'but not before last night.' And he went on to tell how, in his garden, he had seen 'a procession of creatures of the size and colour of green and grey grasshoppers, bearing a body laid out on a rose-leaf, which they buried with songs, and then disappeared'. They are believed to be an omen of death.

Literature

Fairies appeared in medieval romances as one of the beings that a knight errant might encounter. A fairy lady appeared to Sir Launfal and demanded his love; like the fairy bride of ordinary folklore, she imposed a prohibition on him that in time he violated. Sir Orfeo's wife was carried off by the King of Faerie. Huon of Bordeaux is aided by King Oberon.[71] These fairy characters dwindled in number as the medieval era progressed; the figures became wizards and enchantresses.[72] Morgan le Fay, whose connection to the realm of Faerie is implied in her name, in Le Morte d'Arthur is a woman whose magic powers stem from study.[73] While somewhat diminished with time, fairies never completely vanished from the tradition. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight is a late tale, but the Green Knight himself is an otherworldly being.[72] Edmund Spenser featured fairies in The Faerie Queene.[74] In many works of fiction, fairies are freely mixed with the nymphs and satyrs of classical tradition;[75] while in others (e.g. Lamia), they were seen as displacing the Classical beings. 15th century poet and monk John Lydgate wrote that King Arthur was crowned in "the land of the fairy", and taken in his death by four fairy queens, to Avalon where he lies under a "fairy hill", until he is needed again.[76]

Fairies appear as significant characters in William Shakespeare's A Midsummer's Night Dream, which is set simultaneously in the woodland, and in the realm of Fairyland, under the light of the moon.[77] and in which a disturbance of Nature caused by a fairy dispute creates tension underlying the plot and informing the actions of the characters. According to Maurice Hunt, Chair of the English Department at Baylor University, the blurring of the identities of fantasy and reality makes possible “that pleasing, narcotic dreaminess associated with the fairies of the play”.[78]

Shakespeare's contemporary, Michael Drayton features fairies in his Nimphidia; from these stem Alexander Pope's sylphs of The Rape of the Lock, and in the mid 17th century, précieuses took up the oral tradition of such tales to write fairy tales; Madame d'Aulnoy invented the term contes de fée ("fairy tale").[79] While the tales told by the précieuses included many fairies, they were less common in other countries' tales; indeed, the Brothers Grimm included fairies in their first edition, but decided this was not authentically German and altered the language in later editions, changing each "Fee" (fairy) to an enchantress or wise woman.[80] J. R. R. Tolkien described these tales as taking place in the land of Faerie.[81] Additionally, not all folktales that feature fairies are generally categorized as fairy tales.

Fairies in literature took on new life with Romanticism. Writers such as Sir Walter Scott and James Hogg were inspired by folklore which featured fairies, such as the Border ballads. This era saw an increase in the popularity of collecting of fairy folklore, and an increase in the creation of original works with fairy characters.[82] In Rudyard Kipling's Puck of Pook's Hill, Puck holds to scorn the moralizing fairies of other Victorian works.[83] The period also saw a revival of older themes in fantasy literature, such as C.S. Lewis's Narnia books which, while featuring many such classical beings as fauns and dryads, mingles them freely with hags, giants, and other creatures of the folkloric fairy tradition.[84] Victorian flower fairies were popularized in part by Queen Mary’s keen interest in fairy art, and by British illustrator and poet Cicely Mary Barker's series of eight books published in 1923 through 1948. Imagery of fairies in literature became prettier and smaller as time progressed.[85] Andrew Lang, complaining of "the fairies of polyanthuses and gardenias and apple blossoms" in the introduction to The Lilac Fairy Book, observed that "These fairies try to be funny, and fail; or they try to preach, and succeed."[86]

Fairies are seen in Neverland, in Peter and Wendy, the novel version of J. M. Barrie's famous Peter Pan stories, published in 1911, and its character Tinker Bell has become a pop culture icon. When Peter Pan is guarding Wendy from pirates, the story says: "After a time he fell asleep, and some unsteady fairies had to climb over him on their way home from an orgy. Any of the other boys obstructing the fairy path at night they would have mischiefed, but they just tweaked Peter's nose and passed on."[87]

Fairies in Malay Folk Stories

In Malays, fairy/fairies are called 'pari-pari' (Malaysian) or 'peri' (Indonesian). They are often looked as motherly figure helpful creatures who will help those who have good heart.

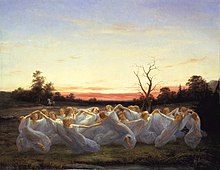

Fairies in art

Images of fairies have appeared as illustrations, often in books of fairy tales, as well as in photographic-based media and sculpture. Some artists known for their depictions of fairies includeCicely Mary Barker, Arthur Rackham, Brian Froud, Alan Lee, Amy Brown, David Delamare, Meredith Dillman, Jasmine Becket-Griffith, Warwick Goble, Kylie InGold, Ida Rentoul Outhwaite, Myrea Pettit, Florence Harrison, Suza Scalora,[88] Nene Thomas, Gustave Doré, Rebecca Guay and Greta James.

The Victorian era was particularly noted for fairy paintings. The Victorian painter Richard Dadd created paintings of fairy-folk with a sinister and malign tone. Other Victorian artists who depicted fairies include John Atkinson Grimshaw, Joseph Noel Paton, John Anster Fitzgerald and Daniel Maclise.[89] Interest in fairy-themed art enjoyed a brief renaissance following the publication of the Cottingley Fairies photographs in 1917 and a number of artists turned to painting fairy themes.

Fairies in religion

Theosophy

In the teachings of Theosophy, Devas, the equivalent of angels, are regarded as living either in the atmospheres of the planets of the solar system (Planetary Angels) or inside the Sun (Solar Angels) (presumably other planetary systems and stars have their own angels) and they are believed to help to guide the operation of the processes of nature such as the process of evolution and the growth of plants; their appearance is reputedly like colored flames about the size of a human being. Some (but not most) devas originally incarnated as human beings. Less important smaller-in-size less evolutionarily developed minor angels are called nature spirits, elementals, and fairies. [90] The Cottingley Fairies photographs in 1917 (revealed by the "photographers" in 1981 to have been faked) were originally believed to have been real by many Theosophists. It is believed by Theosophists that devas, nature spirits, elementals (gnomes, ondines, sylphs, and salamanders), and fairies can be observed when the third eye is activated.[91] It is maintained by Theosophists that these less evolutionarily developed beings have never been previously incarnated as human beings; they are regarded as being on a separate line of spiritual evolution called the “deva evolution”; eventually, as their souls advance as they reincarnate, it is believed they will incarnate as devas.[92]

It is asserted by Theosophists that all of the above mentioned beings possess etheric bodies that are composed of etheric matter, a type of matter finer and more pure that is composed of smaller particles than ordinary physical plane matter.[92]

Fairies in popular culture

- Cottingley Fairies

- List of fairy and sprite characters

- Winx Club

- Wicked Lovely

- Changeling: The Dreaming, a Role Playing Game

- Changeling: The Lost, a Role Playing Game

- Artemis Fowl

- The Southern Vampire Mysteries

See also

Bibliography

- D. L. Ashliman, Fairy Lore: A Handbook (Greenwood, 2006)

- Brian Froud and Alan Lee, Faeries, (Peacock Press/Bantam, New York, 1978)

- Ronan Coghlan Handbook of Fairies (Capall Bann, 2002)

- Lizanne Henderson and Edward J. Cowan, Scottish Fairy Belief: A History (Edinburgh, 2001; 2007)

- C. S. Lewis, The Discarded Image: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature (1964)

- Harmonia Saille "Walking the Faery Pathway", (O Books, London, 2010)

- Patricia Lysaght, The Banshee: the Irish Supernatural Death Messenger (Glendale Press, Dublin, 1986)

- Peter Narvaez, The Good People, New Fairylore Essays (Garland, New York, 1991)

- Eva Pocs, Fairies and Witches at the boundary of south-eastern and central Europe FFC no 243 (Helsinki, 1989)

- Joseph Ritson, Fairy Tales, Now First Collected: To which are prefixed two dissertations: 1. On Pygmies. 2. On Fairies, London, 1831

- Diane Purkiss, Troublesome Things: A History of Fairies and Fairy Stories (Allen Lane, 2000)

- Tomkinson, John L. Haunted Greece: Nymphs, Vampires and other Exotika, (Anagnosis, 2004) ISBN 960-88087-0-7

References

- ^ Briggs, Katharine Mary (1976) An Encyclopedia of Fairies. New York, Pantheon Books. "Euphemistic names for fairies" p. 127 ISBN 0-394-73467-X.

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. xi.

- ^ Lewis, C. S. (1994 (reprint)) The Discarded File: An Introduction to Medieval and Renaissance Literature. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. p. 122 ISBN 0-521-47735-2.

- ^ a b c d e Silver, Carole B. (1999) Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousness. Oxford University Press. p. 47 ISBN 0-19-512199-6.

- ^ a b Yeats, W. B. (1988) "Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry", in A Treasury of Irish Myth, Legend, and Folklore. Gramercy. p.1 ISBN 0-517-489904-X. Cite error: The named reference "Yeats-gods" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Briggs (1976) pp. 335–6.

- ^ a b Briggs (1976) p. 25.

- ^ Kirk, Robert (28 Dec 2007). "1. Of the subterranean inhabitants". The Secret Commonwealth of Elves, Fauns and Fairies. Easy Reading Series. Aberfoyle, Scotland: Forgotten Books. p. 39. ISBN 1605061859. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Briggs (1976) p. 98.

- ^ Yeats (1988) p. 2.

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. 148.

- ^ Briggs, K.M. (1967) The Fairies in English Tradition and Literature. Chicago, University of Chicago Press. p. 71.

- ^ Lewis (1994) p. 136.

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. 15.

- ^ Briggs (1976) pp. 68–9.

- ^ Henry Tegner, Ghosts of The North Country, 1991 Butler Publishing ISBN 0-946928-40-1.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 15.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 141.

- ^ Lewis (1994) p. 134.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 38.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 146.

- ^ Lewis (1994) pp. 135–6.

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. 319.

- ^ Yeats (1988) pp. 9–10.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 9.

- ^ Lewis (1994) p. 137.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Origins of fairies" p. 320.

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. 223.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Traffic with fairies" and "Trooping fairies" pp. 409–12.

- ^ Lewis (1994) p. 138.

- ^ a b c Briggs (1967) pp. 143–7.

- ^ a b Evans-Wentz, W. Y. (1966, 1990) The Fairy-Faith in Celtic Countries. New York, Citadel. pp. 167, 243, 457 ISBN 0-8065-1160-5. Cite error: The named reference "Evans-Wentz" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens and Peter and Wendy, Oxford Press, 1999, p. 32.

- ^ Witchcraft and the Mystery Tradition.

- ^ Yolen, Jane (2000) Touch Magic. p. 49 ISBN 0-87483-591-7.

- ^ a b c Froud, Brian and Lee, Alan (1978) Faeries. New York, Peacock Press ISBN 0-553-01159-6.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 45.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 50.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 44.

- ^ The Religion of the Ancient Celts: Chapter XI. Primitive Nature Worship.

- ^ Silver (1999) pp. 40–1.

- ^ Terri Windling, "Fairies in Legend, Lore, and Literature".

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. 80.

- ^ Briggs (1976) p. 41.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Bells" p. 20.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 74.

- ^ Opie, Iona and Tatem, Moira (eds) (1989) A Dictionary of Superstitions Oxford University Press. p. 38.

- ^ Lewis (1994) p. 125.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 155.

- ^ Lenihan, Eddie and Green, Carolyn Eve (2004) Meeting The Other Crowd: The Fairy Stories of Hidden Ireland. pp. 146–7 ISBN 1-58542-206-1.

- ^ Lenihan (2004) p. 125.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 152.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Brownies" p. 46.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 34.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Infringement of fairy privacy" p. 233.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Fairy morality" p. 115.

- ^ Gauldie, E. (1981) The Scottish Miller 1700 – 1900. Edinburgh, John McDonald. p. 187.

- ^ Silver (1999) p. 167.

- ^ Briggs (1976) pp. 62–66.

- ^ Yeats (1988) p. 47.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Traffic with fairies" and "Trooping fairies" pp. 409-12.

- ^ a b Child, Francis The English and Scottish Popular Ballads.

- ^ http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/child/ch037.htm

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 104.

- ^ Briggs (1967) pp. 50–1.

- ^ De Nugis Curiallium by Walter Map, Edited by F. Tupper & M.B Ogle (Chatto & Windus, London 1924)

- ^ Lenihan (2004) pp. 109–10.

- ^ Northumberland Folk Tales, by Rosalind Kerven (2005) Antony Rowe Ltd, p. 532.]

- ^ "The Good People: New Fairylore Essays" By Peter Narváez. University Press of Kentucky, 1997. Page. 126

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Fairy ointment" p. 156.

- ^ Lewis (1994) pp. 129–30.

- ^ a b Briggs (1976) "Fairies in medieval romances" p. 132.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Morgan Le Fay" p. 303.

- ^ Briggs (1976) "Faerie Queen", p. 130.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 174.

- ^ The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Fairies, Anna Franklin, Sterling Publishing Company, 2004, p. 18.

- ^ Shakespeare, William (1979). Harold F. Brooks (ed.). The Arden Shakespeare "A Midsummer Nights Dream". Methuen & Co. Ltd. cxxv. ISBN 0415026997.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Hunt, Maurice. "Individuation in A Midsummer Night's Dream." South Central Review 3.2 (Summer 1986): 1–13.

- ^ Zipes, Jack (2000) The Great Fairy Tale Tradition: From Straparola and Basile to the Brothers Grimm. W. W. Norton. p. 858 ISBN 0-393-97636-X.

- ^ Tatar, Maria (2003) The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales. Princeton University Press. p. 31 ISBN 0-691-06722-8.

- ^ Tolkien, J. R. R. "On Fairy-Stories", The Tolkien Reader, pp. 10–11.

- ^ Briggs, (1967) pp. 165–7.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 203.

- ^ Briggs (1967) p. 209.

- ^ "Lewis pp. 129-130".

- ^ Lang, Andrew Preface The Lilac Fairy Book.

- ^ J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan in Kensington Gardens as well Peter and Wendy, Oxford Press, 1999, p. 132.

- ^ David Gates (November 29, 1999). "Nothing Here But Kid Stuff". Newsweek. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

- ^ Windling, Terri, "Victorian Fairy Paintings".

- ^ Hodson, Geoffrey, Kingdom of the Gods ISBN 0-7661-8134-0 — Has color pictures of what Devas supposedly look like when observed by the third eye — their appearance is reputedly like colored flames about the size of a human being. Paintings of some of the devas claimed to have been seen by Hodson from his book "Kingdom of the Gods":

- ^ Eskild Tjalve’s paintings of devas, nature spirits, elementals and fairies:

- ^ a b Powell, A.E. The Solar System London:1930 The Theosophical Publishing House (A Complete Outline of the Theosophical Scheme of Evolution) See "Lifewave" chart (refer to index)

External links

- Academic discussion on BBC Radio 4's In Our Time, May 11, 2006 (streaming and podcast)

- Audio recording of a traditional fairy story from Newfoundland, Canada (streaming and downloadable formats)

- Audio recording of a Scandinavian folktale explaining fairy origins (streaming and downloadable formats)