Sodium

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appearance | silvery white metallic | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar°(Na) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sodium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 11 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1: hydrogen and alkali metals | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Ne] 3s1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 370.944 K (97.794 °C, 208.029 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1156.090 K (882.940 °C, 1621.292 °F) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (at 20° C) | 0.9688 g/cm3[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 0.927 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 2573 K, 35 MPa (extrapolated) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.60 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 97.42 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 28.230 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +1 −1,[4] 0[5] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.93 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 186 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 166±9 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 227 pm | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc) (cI2) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Lattice constant | a = 428.74 pm (at 20 °C)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 69.91×10−6/K (at 20 °C)[3] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 142 W/(m⋅K) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 47.7 nΩ⋅m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic[6] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Molar magnetic susceptibility | +16.0×10−6 cm3/mol (298 K)[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 10 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 3.3 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 6.3 GPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 3200 m/s (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 0.69 MPa | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7440-23-5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery and first isolation | Humphry Davy (1807) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Symbol | "Na": from New Latin natrium, coined from German Natron, 'natron' | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of sodium | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Sodium (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈsoʊdiəm/ SOH-dee-əm) is a metallic element with a symbol Na (from Latin natrium or Persian ناترون natrun; perhaps ultimately from Egyptian netjerj), and atomic number 11. It is a soft, silvery-white, highly reactive metal and is a member of the alkali metals within "group 1" (formerly known as 'group IA'). It has one stable isotope, 23Na.

Elemental sodium was first isolated by Humphry Davy in 1807 by passing an electric current through molten sodium hydroxide. Elemental sodium does not occur naturally on Earth, because it quickly oxidizes in air[9] and is violently reactive with water, so it must be stored in a non-oxidizing medium, such as a liquid hydrocarbon. The free metal is used for some chemical synthesis, analysis, and heat transfer applications.

Sodium ion is soluble in water, and is thus present in great quantities in the Earth's oceans and other stagnant bodies of water. In these bodies it is mostly counterbalanced by the chloride ion, causing evaporated ocean water solids to consist mostly of sodium chloride, or common table salt. Sodium ion is also a component of many minerals.

Sodium is an essential element for all animal life (including human) and for some plant species. In animals, sodium ions are used in opposition to potassium ions to build up an electrostatic charge on cell membranes, allowing transmission of nerve impulses when the charge is dissipated. Sodium is thus classified as a "dietary inorganic macro-mineral" for animals. Sodium's relative rarity on land is due to its solubility in water, causing it to be leached into bodies of long-standing water by rainfall. Such is its relatively large requirement in animals, in contrast to its relative scarcity in many inland soils, that herbivorous land animals have developed a special taste receptor for the sodium ion.

Characteristics

At room temperature, sodium metal is soft enough that it can be cut with a knife. In air, the bright silvery luster of freshly exposed sodium will rapidly tarnish. The density of alkali metals generally increases with increasing atomic number, but sodium is denser than potassium. Sodium is a fairly good conductor of heat.

Sodium changes color at high pressures, turning black at 1.5 megabar, becoming a red transparent substance at 1.9 megabar, and is predicted to become clearly transparent at 3 megabar. The high pressure allotropes are insulators and take the form of sodium electride.[10]

Chemical properties

Compared with other alkali metals, sodium is generally less reactive than potassium and more reactive than lithium,[11] in accordance with "periodic law": for example, their reaction in water, chlorine gas, etc.

Sodium reacts exothermically with water: small pea-sized pieces will bounce across the surface of the water until they are consumed by it, whereas large pieces will explode. While sodium reacts with water at room temperature, the sodium piece melts with the heat of the reaction to form a sphere, if the reacting sodium piece is large enough. The reaction with water produces very caustic sodium hydroxide (lye) and highly flammable hydrogen gas. These are extreme hazards. When burned in air, sodium forms sodium peroxide Na2O2, or with limited oxygen, sodium oxide Na2O (unlike lithium, the nitride is not formed). If burned in oxygen under pressure, sodium superoxide NaO2 is produced.

Compounds

Sodium compounds are important to the chemical, glass, metal, paper, petroleum, pyrotechnic, soap, and textile industries. Hard soaps are generally sodium salt of certain fatty acids (potassium produces softer or liquid soaps).[12]

The sodium compounds that are the most important to industries are common salt (NaCl), soda ash (Na2CO3), baking soda (NaHCO3), caustic soda (NaOH), sodium nitrate (NaNO3), di- and tri-sodium phosphates, sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3 · 5H2O), and borax (Na2B4O7·10H2O).[12]

Sodium tends to form water-soluble compounds, such as halides, sulfate, nitrate, carboxylates and carbonates. There are only isolated examples of sodium compounds precipitating from water solution. However, nature provides examples of many insoluble sodium compounds such as the cryolite and the feldspars (aluminium silicates of sodium, potassium and calcium). There are other insoluble sodium salts such as sodium bismuthate NaBiO3, sodium octamolybdate Na2Mo8O25·4H2O, sodium thioplatinate Na4Pt3S6, sodium uranate Na2UO4. Sodium meta-antimonate's 2NaSbO3·7H2O solubility is 0.3 g/L as is the pyro form Na2H2Sb2O7·H2O of this salt. Sodium metaphosphate NaPO3 has a soluble and an insoluble form.[13]

Spectroscopy

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

When sodium or its compounds are introduced into a flame, they turn the flame a bright yellow color.

One atomic spectral line of sodium vapor is the so-called D-line, which may be observed directly as the sodium flame-test line and also the major light output of low-pressure sodium lamps (these produce an unnatural yellow, rather than the peach-colored glow of high pressure lamps). The D-line is one of the classified Fraunhofer lines observed in the visible spectrum of the Sun's electromagnetic radiation. Sodium vapor in the upper layers of the Sun creates a dark line in the emitted spectrum of electromagnetic radiation by absorbing visible light in a band of wavelengths around 589.5 nm. This wavelength corresponds to transitions in atomic sodium in which the valence-electron transitions from a 3p to 3s electronic state. Closer examination of the visible spectrum of atomic sodium reveals that the D-line actually consists of two lines called the D1 and D2 lines at 589.6 nm and 589.0 nm, respectively. This fine structure results from a spin-orbit interaction of the valence electron in the 3p electronic state. The spin-orbit interaction couples the spin angular momentum and orbital angular momentum of a 3p electron to form two states that are respectively notated as 3p(2P0

1/2) and 3p(2P0

3/2) in the LS coupling scheme. The 3s state of the electron gives rise to a single state which is notated as 3s(2S1/2) in the LS coupling scheme. The D1-line results from an electronic transition between 3s(2S1/2) lower state and 3p(2P0

1/2) upper state. The D2-line results from an electronic transition between 3s(2S1/2) lower state and 3p(2P0

3/2) upper state. Even closer examination of the visible spectrum of atomic sodium would reveal that the D-line actually consists of a lot more than two lines. These lines are associated with hyperfine structure of the 3p upper states and 3s lower states. Many different transitions involving visible light near 589.5 nm may occur between the different upper and lower hyperfine levels.[14][15][16]

A practical use for lasers which work at the sodium D-line transition is to create artificial laser guide stars (artificial star-like images from sodium in the upper atmosphere) which assist in the adaptive optics for large land-based visible light telescopes.

Isotopes

Nearly twenty isotopes of sodium have been recognized, the only stable one being 23Na. Sodium has two radioactive cosmogenic isotopes which are also the two isotopes with longest half-life, 22Na, with a half-life of 2.6 years and 24Na with a half-life of 15 hours. All other isotopes have a half-life of less than one minute.[17]

Acute neutron radiation exposure (e.g., from a nuclear criticality accident) converts some of the stable 23Na in human blood plasma to 24Na. By measuring the concentration of this isotope, the neutron radiation dosage to the victim can be computed.[18]

History

Salt has been an important commodity in human activities, as testified by the English word salary, referring to salarium, the wafers of salt sometimes given to Roman soldiers along with their other wages.

In medieval Europe a compound of sodium with the Latin name of sodanum was used as a headache remedy. The name sodium probably originates from the Arabic word suda meaning headache as the headache-alleviating properties of sodium carbonate or soda were well known in early times.[19]

Sodium's chemical abbreviation Na was first published by Jöns Jakob Berzelius in his system of atomic symbols (Thomas Thomson, Annals of Philosophy[20]) and is a contraction of the element's new Latin name natrium which refers to the Egyptian natron,[19] the word for a natural mineral salt whose primary ingredient is hydrated sodium carbonate. Hydrated sodium carbonate historically had several important industrial and household uses later eclipsed by soda ash, baking soda and other sodium compounds.

Although sodium (sometimes called "soda" in English) has long been recognized in compounds, it was not isolated until 1807 by Humphry Davy through the electrolysis of caustic soda.[21][22]

Sodium imparts an intense yellow color to flames. As early as 1860, Kirchhoff and Bunsen noted the high sensitivity that a flame test for sodium could give. They state in Annalen der Physik und Chemie in the paper "Chemical Analysis by Observation of Spectra":[23]

In a corner of our 60 m3 room farthest away from the apparatus, we exploded 3 mg. of sodium chlorate with milk sugar while observing the nonluminous flame before the slit. After a while, it glowed a bright yellow and showed a strong sodium line that disappeared only after 10 minutes. From the weight of the sodium salt and the volume of air in the room, we easily calculate that one part by weight of air could not contain more than 1/20 millionth weight of sodium.

Creation

Stable forms of sodium are created in stars through nuclear fusion by fusing two carbon atoms together. This requires temperatures above 600 megakelvins, and a large star with at least three solar masses.[24][25][26][27]

Occurrence

Owing to its high reactivity, sodium is found in nature only as a compound and never as the free element. Sodium makes up about 2.6% by weight of the Earth's crust, making it the sixth most abundant element overall[28] and the most abundant alkali metal. Sodium is found in many different minerals, of which the most common is ordinary salt (sodium chloride), which occurs in vast quantities dissolved in seawater, as well as in solid deposits (halite). Others include amphibole, cryolite, soda niter and zeolite.

Sodium is relatively abundant in stars and the D spectral lines of this element are among the most prominent in star light. Though elemental sodium has a rather high vaporization temperature, its relatively high abundance and very intense spectral lines have allowed its presence to be detected by ground telescopes and confirmed by spacecraft (Mariner 10 and MESSENGER) in the thin atmosphere of the planet Mercury.[29]

Commercial production

Sodium was first produced commercially in 1855 by thermal reduction of sodium carbonate with carbon at 1100 °C, in what is known as the Deville process.[30][31][32]

- Na2CO3 (l) + 2 C (s) → 2 Na (g) + 3 CO (g)

A process based on the reduction of sodium hydroxide was developed in 1886.[30]

Sodium is now produced commercially through the electrolysis of liquid sodium chloride, based on a process patented in 1924.[33][34] This is done in a Downs Cell in which the NaCl is mixed with calcium chloride to lower the melting point below 700 °C. As calcium is less electropositive than sodium, no calcium will be formed at the anode. This method is less expensive than the previous Castner process of electrolyzing sodium hydroxide.

Very pure sodium can be isolated by the thermal decomposition of sodium azide.[35]

Sodium metal in reagent-grade sold for about $1.50/pound ($3.30/kg) in 2009 when purchased in tonne quantities. Lower purity metal sells for considerably less. The market in this metal is volatile due to the difficulty in its storage and shipping. It must be stored under a dry inert gas atmosphere or anhydrous mineral oil to prevent the formation of a surface layer of sodium oxide or sodium superoxide. These oxides can react violently in the presence of organic materials. Sodium will also burn violently when heated in air.[36]

Smaller quantities of sodium, such as a kilogram, cost far more, in the range of $165/kg. This is partially due to the cost of shipping hazardous material. [37]

Applications

Metallic sodium

- Sodium in its metallic form can be used to refine some reactive metals, such as zirconium and potassium, from their compounds.

- In certain alloys to improve their structure.

- To descale metal (make its surface smooth).[38][39]

- As a strong reducing agent.

- To purify molten metals. Especially where Carbon, Aluminium etc. cannot be used for reducing metallic compounds.

- sodium vapor lamps are an efficient means of producing light from electricity and they are often used for street lighting in cities. Low-pressure sodium lamps give a distinctive yellow-orange light which consists primarily of the twin sodium D lines. High-pressure sodium lamps give a more natural peach-colored light, composed of wavelengths spread much more widely across the spectrum.[40][41]

- As a heat transfer fluid in sodium-cooled fast reactors[42] and inside the hollow valves of high-performance internal combustion engines.

- In organic synthesis, sodium is used as a reducing agent, for example in the Birch reduction. It is also used for preparing Na-Extract which is a major method of identification of elements present in organic compound.

- In chemistry, sodium is often used either alone or with potassium in an alloy, NaK as a desiccant for drying solvents. Used with benzophenone, it forms an intense blue coloration when the solvent is dry and oxygen-free.

- The sodium fusion test uses sodium's high reactivity, low melting point, and the near-universal solubility of its compounds, to qualitatively analyze compounds.

Nuclear reactor cooling

Molten sodium is used as a coolant in some types of fast neutron reactors. It has a low neutron absorption cross section, which is required to achieve a high enough neutron flux, and has excellent thermal conductivity. Its high boiling point allows the reactor to operate at ambient pressure. However, using sodium poses certain challenges. The molten metal will readily burn in air and react violently with water, liberating explosive hydrogen. During reactor operation, a small amount of sodium-24 is formed as a result of neutron activation, making the coolant radioactive.

Sodium leaks and fires were a significant operational problem in the first large sodium-cooled fast reactors, causing extended shutdowns at the Monju Nuclear Power Plant and Beloyarsk Nuclear Power Plant.

Where reactors need to be frequently shut down, as is the case with some research reactors, the alloy of sodium and potassium called NaK is used. It melts at −11 °C, so cooling pipes will not freeze at room temperature. Extra precautions against coolant leaks need to be taken in case of NaK, because molten potassium will spontaneously catch fire when exposed to air.

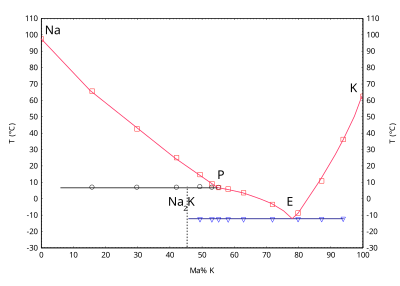

The phase diagram with potassium shows that the mixtures with potassium are liquid at room temperature in a wide concentration range. A compound Na2K melts at 7 °C. The eutectic mixture with a potassium content of 77 % gives a melting point at −12.6 °C.[43]

Compounds

- In soap, as sodium salts of fatty acids. Sodium soaps are harder (higher melting) soaps than potassium soaps.

- In some medicine formulations, the salt form of the active ingredient usually with sodium or potassium is a common modification to improve bioavailability.

- Sodium chloride (NaCl), a compound of sodium ions and chloride ions, is an important heat transfer material.

Botany

Although sodium is not considered an essential micronutrient in most plants, it is necessary in the metabolism of some C4 plants, e.g. Rhodes grass, amaranth, Joseph's coat, and pearl millet.[44] Within these C4 plants, sodium is used in the regeneration of phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) and the synthesis of chlorophyll. In addition, the presence of sodium can offset potassium requirements in many plants by substituting in several roles, such as: maintaining turgor pressure, serving as an accompanying cation in long distance transport, and aiding in stomatal opening and closing.[45]

Increasing soil salinity, osmotic stress and sodium toxicity in plants, especially in agricultural crops, have become worldwide phenomena. High levels of sodium in the soil solution limit the plants' ability to uptake water due to decreased soil water potential and, therefore, may result in wilting of the plant. In addition, excess sodium within the cytoplasm of plant cells can lead to enzyme inhibition, which may result in symptoms such as necrosis, chlorosis, and possible plant death.[46] To avoid such symptoms, plants have developed methods to combat high sodium levels, such as: mechanisms limiting sodium uptake by roots, compartmentalization of sodium in cell vacuoles, and control of sodium in long distance transport.[47] Many plants store excess sodium in old plant tissue, limiting damage to new growth.

Sodium in humans

Sodium is an essential nutrient that regulates blood volume and blood pressure, "maintains the right balance of fluids in the body, transmits nerve impulses, and influences the contraction and relaxation of muscles".[48] It is also necessary for maintaining osmotic equilibrium and the acid-base balance. The minimum physiological requirement for sodium is only 500 milligrams per day.[49] However, according to the American Heart Association, in order to "ensure nutrient adequacy and replace sweat losses a healthy adult needs 1,500 milligrams of sodium per day" or 2/3 of a teaspoon.[50]

Maintaining body fluid volume in animals

The serum sodium and urine sodium play important roles in medicine, both in the maintenance of sodium and total body fluid homeostasis, and in the diagnosis of disorders causing homeostatic disruption of salt/sodium and water balance.

In mammals, decreases in blood pressure and decreases in sodium concentration sensed within the kidney result in the production of renin, a hormone which acts in a number of ways, one of them being to act indirectly to cause the generation of aldosterone, a hormone which decreases the excretion of sodium in the urine. As the body of the mammal retains more sodium, other osmoregulation systems which sense osmotic pressure in part from the concentration of sodium and water in the blood, act to generate antidiuretic hormone. This, in turn, causes the body to retain water, thus helping to restore the body's total amount of fluid.

There is also a counterbalancing system, which senses volume. As fluid is retained, receptors in the heart and vessels which sense distension and pressure, cause production of atrial natriuretic peptide, which is named in part for the Latin word for sodium. This hormone acts in various ways to cause the body to lose sodium in the urine. This causes the body's osmotic balance to drop (as low concentration of sodium is sensed directly), which in turn causes the osmoregulation system to excrete the "excess" water. The net effect is to return the body's total fluid levels back toward normal.

Maintaining electric potential in animal tissues

Sodium cations are important in neuron (brain and nerve) function, and in influencing osmotic balance between cells and the interstitial fluid, with their distribution mediated in all animals (but not in all plants) by the so-called Na+/K+-ATPase pump.[51] Sodium is the chief cation in fluid residing outside cells in the mammalian body (the so-called extracellular compartment), with relatively little sodium residing inside cells. The volume of extracellular fluid is typically 15 liters in a 70 kg human, and the 50 grams of sodium it contains is about 90% of the body's total sodium content.

Dietary uses

The most common sodium salt, sodium chloride ('table salt' or 'common salt'), is used for seasoning and warm-climate food preservation, such as pickling and making jerky (the high osmotic content of salt inhibits bacterial and fungal growth). The human requirement for sodium in the diet is about 1.5 grams per day.[52] This is less than a tenth of the sodium in many diets "seasoned to taste." Most people consume far more sodium than is physiologically needed. Low sodium intake may lead to sodium deficiency (hyponatremia).

Persons suffering from severe dehydration caused by diarrhea, such as that by cholera, can be treated with oral rehydration therapy, in which they drink a solution of sodium chloride, potassium chloride and glucose. This simple, effective therapy saves the lives of millions of children annually in the developing world.

US consumption and guidelines

The 2010 dietary guidelines of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) recommend to decrease the sodium consumption to less than 2.3 g per day (1 teaspoon of salt). This target is lowered to 1.5 g/day (2/3 teaspoon) for "salt sensitive populations", which includes individuals older than 51, African Americans or those who have hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney diseases, and comprises about 50% of the US population.[53] The American Heart Association (AHA) proposes to lower the upper threshold to 2 g/day by 2013 and to 1.5 g/day by 2020 for everyone.[50]

According to the USDA, consumption of sodium in the US is disproportionately greater than the recommended intake, and AHA estimates the daily intake of sodium as 3.4 g/day. NHANES reported that in 2005–2006 the lowest consumption was by 2–5 years old females (~2.1 g/day) and the highest was for 30–39 years old males (~4.7 g/day); males consumed more than 2.3 g/day regardless of age and more than females of the same age group.[53]

Dietary sodium exposure

Dietary sodium comes from table salt, natural sources and processed foods. Processed foods contain an elevated amount of sodium, along with fast food and also foods that do not taste salty such as cheeses. Primary exposure to sodium in North America (77%) comes from highly processed foods or frozen meals. Secondary exposure is correlated with eating at restaurants, predominately fast food chains. Tertiary exposure is experienced when individuals add table salt to their meals during preparation or after they are cooked. Thus simply removing salt shakers from dining tables will not resolve the problem of excessive sodium intake, and the cooperation of food manufacturers and restaurants to reduce the sodium content will be essential. The AHA urges food manufacturers and restaurants to reduce the salt they add to food by 50% over the next 10 years.[50]

Economic impact

Regular consumption of more than 2.3 g/day of sodium promotes such health problems as elevated blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Excessive sodium consumption causes 9–17% of cases of hypertension.[54] Approximately 65 million adults in the United States, and 1 billion adults throughout the world have hypertension.[55] Worldwide, 7.6 million premature deaths (about 13.5% of the global total) and 92 million disability_adjusted life years (6.0% of the global total) can be attributed to high blood pressure.[56] In 2010, the AHA estimated that the costs associated with hypertension and cardiovascular disease amounted to $503 billion dollars, that is people with cardiovascular disease and hypertension cost more than any other diagnostic group. AHA speculates that billions of dollars and approximately 8.5 million deaths between 2006 and 2015 could be averted globally if salt consumption was reduced in accordance with the 2010 dietary guidelines.[57]

Precautions

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2008) |

Extreme care is required in handling elemental/metallic sodium. Sodium is potentially explosive in water (depending on quantity), and it is rapidly converted to sodium hydroxide on contact with moisture and sodium hydroxide is a corrosive substance. The powdered form may combust spontaneously in air or oxygen. Sodium must be stored either in an inert (oxygen and moisture free) atmosphere (such as nitrogen or argon), or under a liquid hydrocarbon such as mineral oil or kerosene.

The reaction of sodium and water is a familiar one in chemistry labs, and is reasonably safe if amounts of sodium smaller than a pencil eraser are used and the reaction is done behind a plastic shield by people wearing eye protection. However, the sodium-water reaction does not scale up well, and is treacherous when larger amounts of sodium are used. Larger pieces of sodium melt under the heat of the reaction, and the molten ball of metal is buoyed up by hydrogen and may appear to be stably reacting with water, until splashing covers more of the reaction mass, causing thermal runaway and an explosion which scatters molten sodium, lye solution, and sometimes flame. (18.5 g explosion [58]) This behavior is unpredictable, and among the alkali metals it is usually sodium which invites this surprise phenomenon, because lithium is not reactive enough to do it, and potassium is so reactive that chemistry students are not tempted to try the reaction with larger potassium pieces.

Sodium is much more reactive than magnesium; a reactivity which can be further enhanced due to sodium's much lower melting point. When sodium catches fire in air (as opposed to just the hydrogen gas generated from water by means of its reaction with sodium) it more easily produces temperatures high enough to melt the sodium, exposing more of its surface to the air and spreading the fire.

Few common fire extinguishers work on sodium fires. Water, of course, exacerbates sodium fires, as do water-based foams. CO2 and Halon are often ineffective on sodium fires, which reignite when the extinguisher dissipates. Among the very few materials effective on a sodium fire are Pyromet and Met-L-X. Pyromet is a NaCl/(NH4)2HPO4 mix, with flow/anti-clump agents. It smothers the fire, drains away heat, and melts to form an impermeable crust. This is the standard dry-powder canister fire extinguisher for all classes of fires. Met-L-X is mostly sodium chloride, NaCl, with approximately 5% Saran plastic as a crust-former, and flow/anti-clumping agents. It is most commonly hand-applied, with a scoop. Other extreme fire extinguishing materials include Lith+, a graphite based dry powder with an organophosphate flame retardant; and Na+, a Na2CO3-based material. Alternatively, plain dry sand can effectively slow down the oxygen and humidity flow to the sodium.

Because of the reaction scale problems discussed above, disposing of large quantities of sodium (more than 10 to 100 grams) must be done through a licensed hazardous materials disposer. Smaller quantities may be broken up and neutralized carefully with ethanol (which has a much slower reaction than water), or even methanol (where the reaction is more rapid than ethanol's but still less than in water), but care should nevertheless be taken, as the caustic products from the ethanol or methanol reaction are just as hazardous to eyes and skin as those from water. After the alcohol reaction appears complete, and all pieces of reaction debris have been broken up or dissolved, a mixture of alcohol and water, then pure water, may then be carefully used for a final cleaning. This should be allowed to stand a few minutes until the reaction products are diluted more thoroughly and flushed down the drain. The purpose of the final water soaking and washing of any reaction mass or container which may contain sodium, is to ensure that alcohol does not carry unreacted sodium into the sink trap, where a water reaction may generate hydrogen in the trap space which can then be potentially ignited, causing a confined sink trap explosion.

See also

References

- ^ "Standard Atomic Weights: Sodium". CIAAW. 2005.

- ^ Prohaska, Thomas; Irrgeher, Johanna; Benefield, Jacqueline; Böhlke, John K.; Chesson, Lesley A.; Coplen, Tyler B.; Ding, Tiping; Dunn, Philip J. H.; Gröning, Manfred; Holden, Norman E.; Meijer, Harro A. J. (4 May 2022). "Standard atomic weights of the elements 2021 (IUPAC Technical Report)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. doi:10.1515/pac-2019-0603. ISSN 1365-3075.

- ^ a b c Arblaster, John W. (2018). Selected Values of the Crystallographic Properties of Elements. Materials Park, Ohio: ASM International. ISBN 978-1-62708-155-9.

- ^ Greenwood, Norman N.; Earnshaw, Alan (1997). Chemistry of the Elements (2nd ed.). Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-08-037941-8.

- ^ The compound NaCl has been shown in experiments to exists in several unusual stoichiometries under high pressure, including Na3Cl in which contains a layer of sodium(0) atoms; see Zhang, W.; Oganov, A. R.; Goncharov, A. F.; Zhu, Q.; Boulfelfel, S. E.; Lyakhov, A. O.; Stavrou, E.; Somayazulu, M.; Prakapenka, V. B.; Konôpková, Z. (2013). "Unexpected Stable Stoichiometries of Sodium Chlorides". Science. 342 (6165): 1502–1505. arXiv:1310.7674. Bibcode:2013Sci...342.1502Z. doi:10.1126/science.1244989. PMID 24357316. S2CID 15298372.

- ^ Magnetic susceptibility of the elements and inorganic compounds, in Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Weast, Robert (1984). CRC, Handbook of Chemistry and Physics. Boca Raton, Florida: Chemical Rubber Company Publishing. pp. E110. ISBN 0-8493-0464-4.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Sodium, chemicool.com. Retrieved 10 November 2010.

- ^ Stony Brook University (12 March 2009). "Metal Becomes Transparent Under High Pressure". Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ^ De Leon, N. "Reactivity of Alkali Metals". Indiana University Northwest. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ^ a b Holleman, Arnold F. (1985). "Natrium". Lehrbuch der Anorganischen Chemie (in German) (91–100 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. pp. 931–943. ISBN 3-11-007511-3.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Dean, John Aurie; Lange, Norbert Adolph (1998). Lange's Handbook of Chemistry. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0070163847.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Citron; M. L.; et al. (1977). "Experimental study of power broadening in a two level atom". Physical Review A. 16 (4): 1507. Bibcode:1977PhRvA..16.1507C. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.16.1507.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help) - ^ Steck, Daniel A. "Sodium D. Line Data" (PDF). Los Alamos National Laboratory (technical report).

- ^ Milonni, Peter W; Eberly, Joseph H (12 June 2009). "Laser Physics": 118–120. ISBN 9780470387719.

{{cite journal}}:|chapter=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Audi, Georges (2003). "The NUBASE Evaluation of Nuclear and Decay Properties". Nuclear Physics A. 729. Atomic Mass Data Center: 3–128. Bibcode:2003NuPhA.729....3A. doi:10.1016/j.nuclphysa.2003.11.001.

- ^ Sanders, F. W. (1962). "Neutron Activation of Sodium in Anthropomorphous Phantoms". Health Physics. 8 (4): 371–379. doi:10.1097/00004032-196208000-00005. PMID 14496815.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Newton, David E. Chemical Elements. ISBN 0-7876-2847-6.

- ^ van der Krogt, Peter. "Elementymology & Elements Multidict". Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ Davy, Humphry (1808). "On some new phenomena of chemical changes produced by electricity, particularly the decomposition of the fixed alkalies, and the exhibition of the new substances which constitute their bases; and on the general nature of alkaline bodies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 98: 1–44. doi:10.1098/rstl.1808.0001.

- ^ Weeks, Mary Elvira (1932). "The discovery of the elements. IX. Three alkali metals: Potassium, sodium, and lithium". Journal of Chemical Education. 9 (6): 1035. Bibcode:1932JChEd...9.1035W. doi:10.1021/ed009p1035.

- ^ Kirchhoff, G.; Bunsen, R. (1860). "Chemische Analyse durch Spectralbeobachtungen". Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 186 (6): 161–189. Bibcode:1860AnP...186..161K. doi:10.1002/andp.18601860602.

- ^ Denisenkov, P. A.; Ivanov, V. V. (1987). "Sodium Synthesis in Hydrogen Burning Stars". Soviet Astr.lett.(Tr:pisma) V.13. 13: 214. Bibcode:1987SvAL...13..214D.

- ^ Francois, P. (1986). "Nucleosynthesis of the light metals in the Galaxy - A study of sodium enrichment". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 165 (1–2): 183–188. Bibcode:1986A&A...165..183F.

- ^ Lambert, David L. (1987). "Chemical evolution of the galaxy: Abundances of the light elements (sodium to calcium)" (PDF). Journal of Astrophysics and Astronomy. 8 (2): 103–122. Bibcode:1987JApA....8..103L. doi:10.1007/BF02714309.

- ^ Baumueller, D.; Butler, K.; Gehren, T. (1998). "Sodium in the Sun and in metal-poor stars". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 338: 637–650. Bibcode:1998A&A...338..637B.

- ^ Lide, D. R., ed. (2005). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (86th ed.). Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press. ISBN 0-8493-0486-5.

- ^ Tjrhonsen, Dietrick E. (17 August 1985). "Sodium found in Mercury's atmosphere". BNET. Retrieved 18 September 2008.

- ^ a b Eggeman, Tim. Sodium and Sodium Alloys. Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Published online 2007. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1915040912051311.a01.pub2

- ^ Oesper, R. E.; Lemay, P. (1950). "Henri Sainte-Claire Deville, 1818-1881". Chymia. 3: 205–221. JSTOR 27757153.

- ^ Banks, Alton (1990). "Sodium". Journal of Chemical Education. 67 (12): 1046. Bibcode:1990JChEd..67.1046B. doi:10.1021/ed067p1046.

- ^ Pauling, Linus, General Chemistry, 1970 ed., Dover Publications

- ^ "Los Alamos National Laboratory – Sodium". Retrieved 8 June 2007.

- ^ Merck Index, 9th ed., monograph 8325

- ^ "Sodium Metal 99.97% Purity". Galliumsource.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ "007-Sodium Metal". Mcssl.com. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- ^ Stampers, National Association of Drop Forgers and (1957). Metal treatment and drop forging.

- ^ Harris, Jay C (1949). Metal cleaning bibliographical abstracts. p. 76.

- ^ Lindsey, Jack L (1997). Applied illumination engineering. pp. 112–. ISBN 9780881732122.

- ^ Kane, Raymond; Sell, Heinz (2001). Revolution in lamps: A chronicle of 50 years of progress. pp. 241–. ISBN 9780881733518.

- ^ Sodium as a Fast Reactor Coolant presented by Thomas H. Fanning. Nuclear Engineering Division. U.S. Department of Energy. U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Topical Seminar Series on Sodium Fast Reactors. May 3, 2007

- ^ van Rossen, G.L.C.M.; van Bleiswijk, H. (1912). "Über das Zustandsdiagramm der Kalium-Natriumlegierungen". Z. Anorg. Chem. 74: 152–156. doi:10.1002/zaac.19120740115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kering, M. K. "Manganese Nutrition and Photosynthesis in NAD-malic enzyme C4 plants". Ph.D. dissertation, University of Missouri-Columbia, 2008.

- ^ Subbarao, G. V.; Ito, O.; Berry, W. L.; Wheeler, R. M. (2003). "Sodium—A Functional Plant Nutrient". Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences. 22 (5): 391–416. doi:10.1080/07352680390243495.

- ^ Zhu, J. K. (2001). "Plant salt tolerance". Trends in plant science. 6 (2): 66–71. doi:10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01838-0. PMID 11173290.

- ^ "Plants and salt ion toxicity". Plant Biology. Accessed 11/02/2010

- ^ Sodium: How to tame your salt habit now, Mayo Clinic

- ^ Sodium, Northewestern University

- ^ a b c 2010 Dietary Guidelines, page 4, The American Heart Association, January 23, 2009

- ^ Campbell, Neil (1987). Biology. Menlo Park, Calif.: Benjamin/Cummings Pub. Co. p. 795. ISBN 0-8053-1840-2.

- ^ "It's Your Health". Canadian Government. 2008.

- ^ a b Chapter 3. Foods and Food Components to Reduce, Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2010, USDA

- ^ Geleijnse, JM; Kok, FJ; Grobbee, DE (2004). "Impact of dietary and lifestyle factors on the prevalence of hypertension in Western populations". European journal of public health. 14 (3): 235–239. doi:10.1093/eurpub/14.3.235. PMID 15369026.

- ^ Hajjar, I; Kotchen, TA (2003). "Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988-2000". JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 290 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1001/jama.290.2.199. PMID 12851274.

- ^ Lawes, C. M.; Vander Hoorn, S; Rodgers, A; International Society of Hypertension (2008). "Global burden of blood-pressure-related disease, 2001" (PDF). Lancet. 371 (9623): 1513–1518. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60655-8. PMID 18456100.

- ^ Lloyd-Jones, D.; Adams, R. J.; Brown, T. M.; Carnethon, M.; Dai, S.; De Simone, G.; Ferguson, T. B.; Ford, E.; Furie, K. (2010). "Executive Summary: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2010 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 121 (7): 948–954. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192666. PMID 20177011.

- ^ "Sodium Lake Explosion 1". Video.google.de. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

External links

- Template:PeriodicVideo

- Etymology of "natrium" – source of symbol Na

- The Wooden Periodic Table Table's Entry on Sodium

- Dietary Sodium

- Sodium isotopes data from The Berkeley Laboratory Isotopes Project's