Protofeminism

| Part of a series on |

| Feminism |

|---|

|

|

|

Protofeminist is a term used to define women in a philosophical tradition that anticipated modern feminist concepts, yet lived in a time when the term "feminist" was unknown,[1] that is, prior to the 20th century.[2][3] The precise use of the term is disputed, 18th-century feminism and 19th-century feminism being also subsumed under "feminism" proper.

History

The utility of the term protofeminist is rejected by some modern scholars[4] as some do postfeminist.

Ancient Greece

The role of women is discussed in book five of Plato's The Republic.

"Are dogs divided into hes and shes, or do they both share equally in hunting and in keeping watch and in the other duties of dogs? or do we entrust to the males the entire and exclusive care of the flocks, while we leave the females at home, under the idea that the bearing and suckling their puppies is labour enough for them?"

The Republic states that women in Plato's ideal state should work alongside men, receive equal education and share equally in all aspects of the state. The sole exception was that women were to work in capacities which did not require as much physical strength.[5]

Middle East

In the Middle East during the Middle Ages, an early effort to improve the status of women occurred during the early reforms under Islam, when women were given greater rights in marriage, divorce and inheritance.[6] Women were not accorded with such legal status in other cultures, including the West, until centuries later.[7] The Oxford Dictionary of Islam states that the general improvement of the status of Arab women included prohibition of female infanticide and recognizing women's full personhood.[8] "The dowry, previously regarded as a bride-price paid to the father, became a nuptial gift retained by the wife as part of her personal property."[6][9] Under Islamic law, marriage was no longer viewed as a "status" but rather as a "contract", in which the woman's consent was imperative.[6][8][9] "Women were given inheritance rights in a patriarchal society that had previously restricted inheritance to male relatives."[6] Annemarie Schimmel states that "compared to the pre-Islamic position of women, Islamic legislation meant an enormous progress; the woman has the right, at least according to the letter of the law, to administer the wealth she has brought into the family or has earned by her own work."[10]

The Islamic studies professor William Montgomery Watt states:

It is true that Islam is still, in many ways, a man's religion. But I think I’ve found evidence in some of the early sources that seems to show that Muhammad made things better for women. It appears that in some parts of Arabia, notably in Mecca, a matrilineal system was in the process of being replaced by a patrilineal one at the time of Muhammad. Growing prosperity caused by a shifting of trade routes was accompanied by a growth in individualism. Men were amassing considerable personal wealth and wanted to be sure that this would be inherited by their own actual sons, and not simply by an extended family of their sisters’ sons. This led to a deterioration in the rights of women. At the time Islam began, the conditions of women were terrible - they had no right to own property, were supposed to be the property of the man, and if the man died everything went to his sons. Muhammad improved things quite a lot. By instituting rights of property ownership, inheritance, education and divorce, he gave women certain basic safeguards. Set in such historical context the Prophet can be seen as a figure who testified on behalf of women's rights.[11]

Though there have been some who have claimed that is evidence of matrilineality in pre-Islamic Arabia, from the Amirites of Yemen to the Nabateans in Northern Arabia.[12] Some have speculated that Mohammed's had a motivation that was precisely to remove matrilineality and install a purely patriarchal system to which they attribute to being witness today. Shulamith Shahar believed that his wife Khadijah was the last successful businesswoman one could find in Arabia. And that there was evidence that Khadijah was the norm, not the exception, before Mohammed's rule over Arabia. That after Muhammed's revolution, the Arabian businesswoman disappears. She believes that it is likely that Muhammed specifically targeted the matrilineal system and replaced it with what she believes as the most a strictest patrilineal system ever witnessed. Far from being a "proto-feminist", Muhammed would therefore instead be the one who removed rights that at time where widely available to women both in Europe and in Asia.[13]

Some have claimed that women generally had more legal rights under Islamic law than they did under Western legal systems until more recent times.[14] English Common Law transferred property held by a wife at the time of a marriage to her husband, which contrasted with the Sura: "Unto men (of the family) belongs a share of that which Parents and near kindred leave, and unto women a share of that which parents and near kindred leave, whether it be a little or much - a determinate share" (Qur'an 4:7), albeit maintaining that husbands were solely responsible for the maintenance and leadership of his wife and family.[14] "French married women, unlike their Muslim sisters, suffered from restrictions on their legal capacity which were removed only in 1965."[15] Noah Feldman, a law professor at Harvard University, notes:

As for sexism, the common law long denied married women any property rights or indeed legal personality apart from their husbands. When the British applied their law to Muslims in place of Shariah, as they did in some colonies, the result was to strip married women of the property that Islamic law had always granted them — hardly progress toward equality of the sexes.[16]

Whilst in the pre-modern period there was not a formal feminist movement, nevertheless there were a number of important figures who argued for improving women's rights and autonomy. These range from the medieval mystic and philosopher Ibn Arabi, who argued that women could achieve spiritual stations as equally high as men [17] to Nana Asma’u, daughter of eighteenth-century reformer Usman Dan Fodio, who pushed for literacy and education of Muslim women.[18]

Women played an important role in the foundations of many Islamic educational institutions, such as Fatima al-Fihri's founding of the University of Al Karaouine in 859. This continued through to the Ayyubid dynasty in the 12th and 13th centuries, when 160 mosques and madrasahs were established in Damascus, 26 of which were funded by women through the Waqf (charitable trust or trust law) system. Half of all the royal patrons for these institutions were also women.[19] As a result, opportunities for female education arose in the medieval Islamic world. In the 12th century, the Sunni scholar Ibn Asakir wrote that women could study, earn ijazahs (academic degrees), and qualify as scholars and teachers. This was especially the case for learned and scholarly families, who wanted to ensure the highest possible education for both their sons and daughters.[20] Ibn Asakir was in support of female education and had himself studied under eighty different female teachers in his time. Female education in the Islamic world was said to be inspired by Muhammad's wives: Khadijah, a successful businesswoman, and Aisha, a renowned hadith scholar and military leader. According to a hadith attributed to Muhammad, he praised the women of Medina because of their desire for religious knowledge.[21] While there were no legal restrictions on female education, some men did not approve of this practice, such as Muhammad ibn al-Hajj (d. 1336) who was appalled at the behaviour of some women who informally audited lectures in his time:[22]

"[Consider] what some women do when people gather with a shaykh to hear [the recitation of] books. At that point women come, too, to hear the readings; the men sit in one place, the women facing them. It even happens at such times that some of the women are carried away by the situation; one will stand up, and sit down, and shout in a loud voice. [Moreover,] her 'awra will appear; in her house, their exposure would be forbidden — how can it be allowed in a mosque, in the presence of men?"

The labor force in the Caliphate were employed from diverse ethnic and religious backgrounds, while both men and women were involved in diverse occupations and economic activities.[23] Women were employed in a wide range of commercial activities and diverse occupations[24] in the primary sector (as farmers for example), secondary sector (as construction workers, dyers, spinners, etc.) and tertiary sector (as investors, doctors, nurses, presidents of guilds, brokers, peddlers, lenders, scholars, etc.).[25] Muslim women also held a monopoly over certain branches of the textile industry,[24] the largest and most specialized and market-oriented industry at the time, in occupations such as spinning, dyeing, and embroidery. In comparison, female property rights and wage labour were relatively uncommon in Europe until the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries.[26]

In the 12th century, the famous Islamic philosopher and qadi (judge) Ibn Rushd, known to the West as Averroes, claimed that women were equal to men in all respects and possessed equal capacities to shine in peace and in war, citing examples of female warriors among the Arabs, Greeks and Africans to support his case.[27] In early Muslim history, examples of notable female Muslims who fought during the Muslim conquests and Fitna (civil wars) as soldiers or generals included Nusaybah Bint k’ab Al Maziniyyah,[28] Aisha,[29] Kahula and Wafeira,[30] and Um Umarah.

European Renaissance

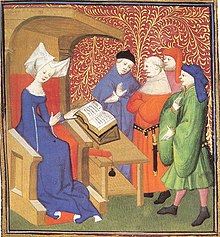

Simone de Beauvoir wrote that "the first time we see a woman take up her pen in defense of her sex" was Christine de Pizan who wrote Épître au Dieu d'Amour (Epistle to the God of Love), as well as The Book of the City of Ladies, at the turn of the 15th century.[31] Catherine of Aragon, the first official female Ambassador in European history, commissioned a book by Juan Luis Vives arguing that women had a right to an education, and encouraged and popularized education for women in England during her time as Henry VIII's wife.

Renaissance humanists such as Vives and Agricola argued that aristocratic women at least required education; Roger Ascham educated Elizabeth I, and she not only read Latin and Greek but wrote occasional poems, such as On Monsieur's Departure, that are still anthologized. However, women who were exceptionally accomplished were described as manly or called witches.[citation needed] Queen Elizabeth I was described as having talent without a woman's weakness, industry with a man's perseverance, and the body of a weak and feeble woman, but with the heart and stomach of a king.[32] The only way she could be seen as a good ruler was for her to be described with manly qualities. Being a powerful and successful woman during the Renaissance, like Queen Elizabeth I meant in some ways being male, a perception that unfortunately gravely limited women's potential as women.[32]

Women were given the sole role and social value of reproduction.[33] This gender role defined a woman's main identity and purpose in life. The ancient philosopher Socrates was well-known as an exemplar to the Renaissance humanists as their role model for the pursuit of wisdom in many subjects. Surprisingly, Socrates has said that the only reason he puts up with his wife, Xanthippe, was because she bore him sons, in the same way one puts up with the noise of geese because they produce eggs and chicks.[34] This analogy from the revered philosopher only propelled the claim that a woman's sole role was to reproduce.

Marriage during the Renaissance was what defined a woman. She was who she married. When unmarried, a woman was the property of her father, and once married, she became the property of her husband. She had few rights, except for any privileges her husband or father gave her. Married women had to obey their husbands and were expected to be chaste, obedient, pleasant, gentle, submissive, and, unless sweet-spoken, silent.[35] In the 1593 A.D. play, The Taming of the Shrew by William Shakespeare, Katherina and Bianca's father treats his daughters like property; the man who gives the best offer gets to marry them. When Katherina is outspoken and wild, society shuns her; she is seen as a wayward woman – a shrew – who needs to be tamed into submission. When Petruchio tames her, she readily goes to him when he summons her, almost like a dog. Her submissiveness is applauded, and the crowds at the party accept her as a proper woman since she is now "conformable to other household Kates".[36]

Education was an element celebrated by society. Men were pushed to go to college and become knowledgeable in many subjects, but women were discouraged from acquiring too much education and told to be obedient wives. A woman named Margherita, living during the Renaissance, learned to read and write at the age of about 30 so there would be no mediating factors between the letters of her and her husband.[37] Although Margherita did defy gender roles, she wanted to become educated not in hopes of becoming a more enlightened person, but because she wanted to be a better wife by being able to communicate to her husband directly. When a woman did involve herself in learning, it was certainly not the norm. In a letter the humanist Leonardo Bruni sent to Lady Baptista Maletesta of Montefeltro in 1424, he wrote

"While you live in these times when learning has so far decayed that is regarded as positively miraculous to meet a learned man, let alone a woman."[38]

The emphasis of a woman shows how it was indeed very rare for a woman to participate in the Renaissance. In general, Bruni thought that women should have an education on par with men, but with one significant exception. In the letter he writes,

"For why should the subtleties of...a thousand...rhetorical conundra consume the powers of a woman, who never sees the forum? The contests of the forum, like those of warfare and battle, are the sphere of men. Hers is not the task of learning to speak for and against witnesses, for and against torture, for and against reputation.... She will, in a word, leave the rough-and-tumble of the forum entirely to men."[38]

The famous Renaissance salons that held intelligent debate and lectures were obviously not welcoming to women. This blatant denial would lead to problems that educated women faced and contribution to the low probability that a woman would get educated in the first place.

During the 16th century, Modesta di Pozzo di Forzi worked in Venice and Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa wrote The Superior Excellence of Women Over Men.[39]

Seventeenth century: nonconformism, protectorate and restoration

Marie de Gournay (1565–1645), the last love of Michel de Montaigne who published posthumously his Essays, wrote two feminist essays, The Equality of Men and Women (1622) and The Ladies' Grievance (1626). In 1673, François Poullain de la Barre wrote De l'égalité des deux sexes (On the equality of the two sexes).[39]

The 17th century saw the development of many nonconformist sects which allowed more say to women than the established religions, especially the Quakers. Noted feminist writers on religion and spirituality included Rachel Speght, Katherine Evans, Sarah Chevers and Margaret Fell.[40][41][42]

This increased participation of women was not without opposition, notably John Bunyan, leading to persecution, and emigration to the Netherlands and the Americas. Over this and preceding centuries women who expressed opinions on religion or preached were also in danger of being suspected of lunacy or witchcraft, and many like Anne Askew[43] died "for their implicit or explicit challenge to the patriarchal order".[44]

In France as in England, feminist ideas were attributes of heterodoxy, such as the Waldensians and Catharists, than orthodoxy. Religious egalitarianism, such as embraced by the Levellers, carried over into gender equality, and therefore had political implications. Leveller women mounted large scale public demonstrations and petitions, although dismissed by the authorities of the day.

This century also saw more women writers emerging, such as Anne Bradstreet, Bathsua Makin, Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle, Lady Mary Wroth,[45][46] and Mary Astell, who depicted women's changing roles and made pleas for their education. However, they encountered considerable hostility, as exemplified by the experiences of Cavendish, and Wroth whose work was not published till the 20th century.

Astell is frequently described as the first feminist writer. However, this depiction fails to recognise the intellectual debt she owed to Schurman, Makin and other women who preceded her. She was certainly one of the earliest feminist writers in English, whose analyses are as relevant to day as in her own time, and moved beyond earlier writers by instituting educational institutions for women.[47][48] Astell and Behn together laid the groundwork for feminist theory in the seventeenth century. No woman would speak out as strongly again, for another century. In historical accounts she is often overshadowed by her younger and more colourful friend and correspondent Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

The liberalisation of social values and secularisation of the English Restoration provided new opportunities for women in the arts, an opportunity that women used to advance their cause. However, female playwrights encountered similar hostility. These included Catherine Trotter, Mary Manley and Mary Pix. The most influential of all[48][49][50] was Aphra Behn, the first Englishwoman to achieve the status of a professional writer. Critics of feminist writing included prominent men such as Alexander Pope.

In continental Europe, important feminist writers included Marguerite de Navarre, Marie de Gournay and Anne Marie van Schurmann (Anna Maria van Schurman) who mounted attacks on misogyny and promoted the education of women. In the New World the Mexican nun, Juana Ines de la Cruz (1651–1695), was advancing the education of women particularly in her essay entitled "Reply to Sor Philotea".[51] By the end of the seventeenth century women's voices were becoming increasingly heard, becoming almost a clamour, at least by educated women. The literature of the last decades of the century being sometimes referred to as the "Battle of the Sexes",[52] and was often surprisingly polemic, such as Hannah Woolley's "The Gentlewoman's Companion".[53] However women received mixed messages, for they also heard a strident backlash, and even self-deprecation by women writers in response. They were also subjected to conflicting social pressures, one of which was less opportunities for work outside the home, and education which sometimes reinforced the social order as much as inspire independent thinking.

See also

References

- ^ Botting Eileen H, Houser Sarah L. "Drawing the Line of Equality": Hannah Mather Crocker on Women's Rights. American Political Science Review (2006), 100: 265-278

- ^ Cott, Nancy F. 1987. The Grounding of Modern Feminism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- ^ Offen, Karen M. 2000. European Feminisms, 1700–1950: A Political History. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- ^ Ferguson, Margaret. Feminism in time. Modern Language Quarterly 2004 65(1): 7-27

- ^ http://classics.mit.edu/Plato/republic.6.v.html

- ^ a b c d Esposito (2005) p. 79

- ^ Lindsay Jones, p.6224

- ^ a b Esposito (2004), p. 339

- ^ a b Khadduri (1978)

- ^ Schimmel (1992) p.65

- ^ Interview with Prof William Montgomery Watt

- ^ Keddie, Nikki: Women in the Middle East: Past and Present (2007)

- ^ Shahar, Shulamith: The Fourth Estate - A History of Women in the Middle Ages (1983)

- ^ a b Dr. Badawi, Jamal A. (September 1971), "The Status of Women in Islam", Al-Ittihad Journal of Islamic Studies, 8 (2)

- ^ Badr, Gamal M.; Mayer, Ann Elizabeth (Winter 1984), "Islamic Criminal Justice", The American Journal of Comparative Law, 32 (1), American Society of Comparative Law: 167–169 167–8, doi:10.2307/840274

- ^ Noah Feldman (March 16, 2008). "Why Shariah?". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ^ Hakim, Souad (2002), "Ibn 'Arabî's Twofold Perception of Woman: Woman as Human Being and Cosmic Principle", Journal of the Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi Society, 31: 1–29

- ^ Mack, Beverly B. (2000), One Woman's Jihad: Nana Asma'u, Scholar and Scribe, USA: Indiana University Press

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lindsay, James E. (2005), Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 197, ISBN 0-313-32270-8

- ^ Lindsay, James E. (2005), Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World, Greenwood Publishing Group, pp. 196 & 198, ISBN 0-313-32270-8

- ^ Lindsay, James E. (2005), Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 196, ISBN 0-313-32270-8

- ^ Lindsay, James E. (2005), Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World, Greenwood Publishing Group, p. 198, ISBN 0-313-32270-8

- ^ Maya Shatzmiller, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b Maya Shatzmiller (1994), Labour in the Medieval Islamic World, Brill Publishers, ISBN 90-04-09896-8, pp. 400–1

- ^ Maya Shatzmiller, pp. 350–62.

- ^ Maya Shatzmiller (1997), "Women and Wage Labour in the Medieval Islamic West: Legal Issues in an Economic Context", Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 40 (2), pp. 174–206 [175–7].

- ^ Ahmad, Jamil (September 1994), "Ibn Rushd", Monthly Renaissance, 4 (9), retrieved 2008-10-14

- ^ Girl Power, ABC News

- ^ Black, Edwin (2004), Banking on Baghdad: Inside Iraq's 7,000 Year History of War, Profit, and Conflict, John Wiley and Sons, p. 34, ISBN 0-471-70895-X

- ^ Hale, Sarah Josepha Buell (1853), Woman's Record: Or, Sketches of All Distinguished Women, from "The Beginning Till A.D. 1850, Arranged in Four Eras, with Selections from Female Writers of Every Age, Harper Brothers, p. 120

- ^ de Beauvoir, Simone, English translation 1953 (1989), The Second Sex, Vintage Books, p. 105, ISBN 0-679-72451-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b [Bridenthal, Renate, Susan Mosher Stuard, and Mary E. Wiesner, eds. Becoming Visible: Women in European History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. 167.]

- ^ [Bridenthal, Renate, Susan Mosher Stuard, and Mary E. Wiesner, eds. Becoming Visible: Women in European History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. 250.]

- ^ [Manetti, Giannozzo. "Life of Socrates"]

- ^ [Bridenthal, Renate, Susan Mosher Stuard, and Mary E. Wiesner, eds. Becoming Visible: Women in European History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. 159-160.]

- ^ [Shakespeare, William. Taming of the Shrew A Comedy. 1887.]

- ^ [Bridenthal, Renate, Susan Mosher Stuard, and Mary E. Wiesner, eds. Becoming Visible: Women in European History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998. 160.]

- ^ a b [Bruni, Leonardo. "Study of Literature to Lady Baptista Maletesta of Montefeltro," 1494.]

- ^ a b Schneir, Miram, 1972 (1994), Feminism: The Essential Historical Writings, Vintage Books, p. xiv, ISBN 0-679-75381-8

{{citation}}:|first=has numeric name (help) - ^ Fraser, Antonia. The weaker vessel: Women's lot in seventeenth century England. Phoenix, London 1984.

- ^ Marshall-Wyatt, Sherrin. Women in the Reformation era. In, Becoming visible: Women in European history, Renate Bridenthal and Claudia Koonz (eds.) Houghton-Mifflin, Boston 1977.

- ^ Thomas, K. Women and the Civil War sects. 1958 Past and Present 13.

- ^ Lerner, Gerda. Religion and the creation of feminist consciousness. Harvard Divinity Bulletin November 2002

- ^ Moses, Claire Goldberg. French Feminism in the 19th Century. Sunshine for Women, 1984 at 7.

- ^ The poems of Lady Mary Roth. Roberts, Josephine A (ed.) Louisiana State University 1983

- ^ Greer, Germaine. Slip-shod sybils Penguin 1999, at 15-6

- ^ Kinnaird, Joan. Mary Astell: Inspired by ideas (1668-1731) in Spender, op. cit. at 29

- ^ a b Walters, Margaret. "Feminism: A very short introduction". Oxford University 2005 (ISBN 0-19-280510-X)

- ^ Goreau, Angeline. Aphra Behn: A scandal to modesty (c. 1640-1689) in Spender op. cit. 8-27

- ^ Woolf, Virginia. A room of one's own. 1928, at 65

- ^ Juana Inés de la Cruz, Sor. Respuesta a Sor Filotea 1691. pub posthum. Madrid 1700

- ^ Upman AH. English femmes savantes at the end of the seventeenth century. Journal of English and Germanic Philology 12 (1913)

- ^ Woolley, Hannah. The Gentlewoman's Companion. London 1675