Gluten-free diet

A gluten-free diet (GF diet) is a diet that excludes foods containing gluten. Gluten is a protein complex found in wheat (including kamut and spelt), barley, rye and triticale. A gluten-free diet is the only medically accepted treatment for celiac disease.[1] Being gluten intolerant can often mean a person may also be wheat intolerant as well as suffer from the related inflammatory skin condition dermatitis herpetiformis,[2] There are a smaller minority of people who suffer from wheat intolerance alone and are tolerant to gluten.

"Despite the health claims for gluten-free eating, there is no published experimental evidence to support such claims for the general population."[3][4] A significant demand has developed for gluten-free food in the United States whether it is needed or not.[5]

A gluten-free diet might also exclude oats. Medical practitioners are divided on whether oats are acceptable to celiac disease sufferers[6] or whether they become cross-contaminated in milling facilities by other grains.[7] Oats may also be contaminated when grown in rotation with wheat when wheat seeds from the previous harvest sprout up the next season in the oat field and are harvested along with the oats.

The exact level at which gluten is harmless for people with celiac disease is uncertain. A 2008 systematic review tentatively concluded that consumption of less than 10 mg of gluten per day for celiac disease patients is unlikely to cause histological abnormalities, although it noted that few reliable studies had been conducted.[8]

Gluten-free food

Gluten-free food is normally seen as a diet for celiac disease, but people with a gluten allergy (an unrelated disease) should also avoid wheat and related grains.

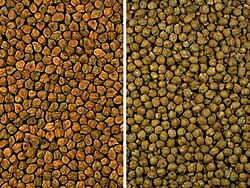

Several grains and starch sources are considered acceptable for a gluten-free diet. The most frequently used are corn, potatoes, rice, and tapioca (derived from cassava). Other grains and starch sources generally considered suitable for gluten-free diets include amaranth, arrowroot, millet, montina, lupin, quinoa, sorghum (jowar), taro, teff, chia seed, almond meal flour, coconut flour, pea flour, cornstarch and yam. Sometimes various types of bean, soybean, and nut flours are used in gluten-free products to add protein and dietary fiber.

Almond flour has a low glycemic index. In spite of its name, buckwheat is not related to wheat. Pure buckwheat is considered acceptable for a gluten-free diet, however, many commercial buckwheat products are mixtures of wheat and buckwheat flours, and thus, not gluten-free. Gram flour, derived from chickpeas, also is gluten-free (this is not the same as Graham flour made from wheat).

Gluten may be used in foods in some unexpected ways, for example it may be added as a stabilizing agent or thickener in products such as ice-cream and ketchup.[9][10]

Cross-contamination issues

A gluten-free diet allows for fresh fruits, vegetables, meats, and many dairy products. The diet allows rice, corn, soy, potato, tapioca, beans, sorghum, quinoa, millet, pure buckwheat, arrowroot, amaranth, teff, Montina, and nut flours and the diet prohibits the ingestion of wheat, barley, rye, and related components, including triticale, durum, graham, kamut, semolina, spelt, malt, malt flavouring, or malt vinegar.[11]

In the United States, the FDA considers foods containing less than or equal to 20 ppm to be gluten-free,[12] but there is no regulation or law in the U.S. for labeling foods as 'gluten-free'. The finding of a current study indicates that some inherently gluten-free grains, seed, and flours not labeled gluten-free are contaminated with gluten. The consumption of these products can lead to inadvertent gluten intake.[13] The use of highly sensitive assays is mandatory to certify gluten-free food products. The European Union, World Health Organization, and Codex Alimentarius require reliable measurement of the wheat prolamins, gliadins rather than all-wheat proteins.[14]

There still is no general agreement on the analytical method used to measure gluten in ingredients and food products.[15] The official limits described in the Codex Draft are 20 ppm for foodstuffs that are considered naturally gluten-free and 200 ppm for foodstuffs rendered gluten-free.[16] The ELISA method was designed to detect w-gliadins, but it suffered from the setback that it lacked sensitivity for barley prolamins.[17]

Cross-contamination problems

A growing body of evidence suggests that a majority of people with celiac disease and following a gluten-free diet can safely consume pure oats in moderate amounts.

Special care is necessary when checking product ingredient lists since gluten comes in many forms: vegetable proteins and starch, modified food starch (when derived from wheat instead of maize), malt flavoring, unless specifically labeled as corn malt. Many ingredients contain wheat or barley derivatives. Maltodextrin is gluten-free, however, since it is highly modified, no matter what the source.[18]

Oats

The suitability of oats in the gluten-free diet is still somewhat controversial. Some research suggests that oats in themselves are gluten-free, but that they are virtually always contaminated by other grains during distribution or processing. Recent research,[19] however, indicated that a protein naturally found in oats (avenin) possessed peptide sequences closely resembling wheat gluten and caused mucosal inflammation in significant numbers of celiac disease sufferers. Some examination results show that even oats that are not contaminated with wheat particles are nonetheless dangerous, while not very harmful to the majority. Such oats are generally considered risky for children with celiac disease to eat, but two studies show that they are completely safe for adults with celiac disease to eat.

People who merely are "gluten-sensitive" may be able to eat oats without adverse effect,[20] even over a period of five years.[21] Given this conflicting information, excluding oats appears to be the only risk-free practice for celiac disease sufferers of all ages,[22] however, medically approved guidelines exist for those with celiac disease who do wish to introduce oats into their diet.[23]

Unless manufactured in a dedicated facility and under gluten-free practices, all cereal grains, including oats, may be cross-contaminated with gluten. Grains become contaminated with gluten by sharing the same farm, truck, mill, or bagging facility as wheat and other gluten-containing grains.

Alcoholic beverages

Several celiac disease groups report that according to the American Dietetic Association's "Manual of Clinical Dietetics",[24][25] many types of alcoholic beverages are considered gluten-free, provided no colourings or other additives have been added as these ingredients may contain gluten. Although most forms of whiskey are distilled from a mash that includes grains that contain gluten, distillation removes any proteins present in the mash, including gluten. Although up to 49% of the mash for Bourbon and up to 20% of the mash for corn whiskey may be made up of wheat, or rye, all-corn Bourbons and corn whiskeys do exist, and are generally labeled as such. Spirits made without any grain such as brandy, wine, mead, cider, sherry, port, rum, tequila, and vermouth generally do not contain gluten. While some vineyards use a flour paste to caulk the oak barrels in which wine is aged,[26] tests have shown that no detectable amounts of gluten are present in the wine from those barrels.[27] A small number of vineyards have also used gluten as a clarifying agent, though it is not the standard process; some studies have shown small amounts of gluten to remain in the wine after clarification.[28] Therefore, some people with Celiac or strong gluten sensitivity may wish to exercise caution. Liqueurs and pre-mixed drinks should be examined carefully for gluten-derived ingredients.

Almost all beers are brewed with malted barley or wheat and will contain gluten. Sorghum and buckwheat-based gluten-free beers are available, but remain a niche market. Some low-gluten beers are also available, however, there is disagreement over the use of gluten products in brewed beverages: Some brewers argue that in certain beers the proteins from such grains as barley or wheat are converted into amino acids during the clarification step of the brewing process and are therefore gluten-free,[29] although there is evidence that this protein degradation is only partial.[30] The Swedish government agency Livsmedelsverket carried out a study of the gluten content in a wide range of beers in 2005 and found that the majority of the beers tested contained less than 200 ppm gluten, with several brands containing less than 20 ppm.[31] However, they also found that many beers have extremely high levels of gluten so, if unsure, coeliacs are advised to avoid beer.

Gluten-free bread

Bread, which is a staple in many diets, typically is made from grains such as wheat that contain gluten. Wheat gluten contributes to the elasticity of dough and is thus an important component of bread. Gluten-free bread is made with ground flours from a variety of materials such as almonds, rice (rice bread), sorghum (sorghum bread), corn (cornbread), or legumes such as beans (bean bread), but since these flours lack gluten it can be difficult for them to retain their shape as they rise and they may be less "fluffy". Additives such as xanthum gum, guar gum, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC), corn starch, or eggs are used to compensate for the lack of gluten.[32]

"Gluten-free" labels

Standards for "gluten-free" labelling have been set up by the "Codex Alimentarius"; however, these regulations fluctuate from one Country to the next. If from within Canada; check with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency for all regulatory procedures for labels and allowed amount of gluten.".[33]

The legal definition of the phrase "gluten-free" varies from country to country. Current research suggests that for persons with celiac disease the maximum safe level of gluten in a finished product is probably less than 0.02% (200 parts per million) and possibly as little as 0.002% (20 parts per million).[citation needed]

In the UK, foods may be labeled gluten-free if they contain less than 0.3% gluten. In Australia, gluten-free foods must contain less than 0.003% gluten.[34] In the processing of gluten-containing grains, gluten is removed as shown in the processing flow below:

Wheat Flour (80,000ppm) > Wheat Starch (200ppm) > Dextrin > Maltodextrin > Glucose Syrup (<5ppm) > Dextrose > Caramel Color

Since ordinary wheat flour contains approximately 12% gluten,[35] even a tiny amount of wheat flour can cross-contaminate a gluten-free product, therefore, considerable care must be taken to prevent cross-contamination in both commercial and home food preparation.

A gluten-free diet rules out all ordinary breads, pastas, and many convenience foods; it also excludes gravies, custards, soups, and sauces thickened with wheat, rye, barley, or other gluten-containing flour. Many countries do not require labeling of gluten containing products, but in several countries (especially Australia and the European Union) new product labeling standards are enforcing the labeling of gluten-containing ingredients. Various gluten-free bakery and pasta products are available from specialty retailers.

In the United States, gluten may not be listed on the labels of certain foods because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has classified gluten as GRAS (Generally Recognized As Safe).[36]

Many so-called gluten-free products, such as chicken bouillon, corn cereal, and caramel ice cream topping, have been found to have been contaminated with gluten.[37] For example, in an investigation reported by the Chicago Tribune on November 21, 2008, Wellshire Farms chicken nuggets labeled "gluten-free" were purchased from a Whole Foods Market and samples were sent to a food allergy laboratory at the University of Nebraska.[38] Results of the testing indicated gluten was present in levels exceeding 2,000 ppm. After the article was published, the products continued to be sold. After receiving customer inquiries, however, more than a month later, the Whole Foods Market removed the product from their shelves. Wellshire Farms has since replaced the batter used in their chicken nuggets.[39]

In the United Kingdom, only cereals currently need to be labeled regarding gluten, while other products are voluntary.[40] For example, most British sausages contain Butcher's Rusk, a grain-derived food additive.[41] Furthermore, while UK companies selling food prepared on their own premises are given guidance by the Food Standards Agency, they are not required to meet any labeling requirements.[42]

Chocolate has a slightly different issue. Pure chocolate is completely gluten free. Manufacturers, however, add various additives to improve taste. Even for chocolate that does not have additives that contain gluten, there is little possibility of contamination with gluten, from the use of machines which previously processed gluten containing food. Nevertheless, several vendors produce chocolate labeled "gluten free".[43]

Lastly, some non-foodstuffs such as medications and vitamin supplements, especially those in tablet form, may contain gluten as an excipient or binding agent.[44][45] People with gluten intolerances may therefore require specialist compounding of their medication.[35]

Regulations

In commerce, the term gluten-free generally is used to indicate a tolerable level of gluten rather than a complete absence.[8]

The current international Codex Alimentarius standard allows for 20 parts per million of gluten in so-called "gluten-free" foods.[46] Such a standard also reflects "the lowest level that can be consistently detected in foods."[47]

Regulation of the label gluten-free varies. In the United States, the FDA issued regulations in 2013 limiting the use of "gluten-free" labels for food products to those with less than 20 parts per million of gluten.[47][48][49]

Popularity and nonceliac health effects

Gluten-free fad diets have become popular. This may be because celiac disease was underdiagnosed and also that people are "unnecessarily turning to the diets as a food fad". There also appears to be an increased incidence of celiac disease, with one study which looked for antibodies from 1950s American blood samples finding that celiac disease is about four times as common as it was.[50] Many are adopting gluten-free diets to treat celiac disease-like symptoms in the absence of a positive test for celiac disease.

A 2011 panel of celiac experts concluded that there is a condition related to gluten other than celiac disease and named it "non-celiac gluten sensitivity".[51] However, for those without celiac disease or gluten sensitivity, the diet is unnecessary.[52][53] There are a wide variety of names which have been used in medical literature for gluten-related disorders which are different from celiac disease. Some of them are confusing and ambiguous. "Non-celiac gluten sensitivity" is the recommended umbrella term for conditions where symptoms different from celiac disease result from ingestion of gluten.[54]

Despite some advocacy, evidence of the diet's efficacy as an autism treatment is poor.[55] Despite vigorous marketing, a variety of studies, including a study by the University of Rochester, found that the popular autism diet does not demonstrate behavioral improvement and fails to show any genuine benefit to children diagnosed with autism who do not also have a known digestive condition which benefits from a gluten-free diet.[56]

Deficiencies linked to maintaining a gluten-free diet

Many gluten-free products are not fortified or enriched by such nutrients as folate, iron, and fiber as traditional breads and cereals have been during the last century.[57] Additionally, because gluten-free products are not always available, many Gluten-Sensitive Enteropathy (GSE) patients do not consume the recommended number of grain servings per day. People who change their standard gluten-free diet to implement gluten-free oats at breakfast, high fiber brown rice bread at lunch, and quinoa as a side at dinner have been found to have significant increases in protein (20.6 g versus 11 g), iron (18.4 mg versus 1.4 mg), calcium (182 mg versus 0 mg), and fiber (12.7 g versus 5 g). The B vitamin group did not have significant increases, but were still found to have improved values of thiamine, riboflavin, niacin, and folate.[58] These dietary changes can greatly reduce a GSE patient's risk for anemia (especially Iron Deficiency Anemia) and low blood calcium levels or poor bone health.

Oats can increase intakes of vitamin B1, magnesium, and zinc in celiac disease patients in remission.[59]

Selenium deficiency in gluten-free diet, combined with malabsorption of selenium in patients with uncontrolled celiac disease is considered a direct factor in the development of comorbid autoimmune thyroid diseases for celiac patients. [60][61]

See also

General:

References

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02768.x, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02768.xinstead. - ^ "Coeliac Disease". National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health. 2008.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.009, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.jand.2012.06.009instead. - ^ De Palma, Giada (2009). "Effects of a gluten-free diet on gut microbiota and immune function in healthy adult human subjects". British Journal of Nutrition. 102: 1154–1160. doi:10.1017/S0007114509371767. Retrieved July 25, 2013.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kenneth Chang (February 4, 2013). "Gluten-Free, Whether You Need It or Not" ("Well" blog by expert journalist). The New York Times. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

The definition is less a diagnosis than a description — someone who does not have celiac, but whose health improves on a gluten-free diet and worsens again if gluten is eaten. It could even be more than one illness.

- ^ N Y Haboubi, S Taylor, S Jones (2006). "Celiac disease and oats: a systematic review". The Fellowship of Postgraduate Medicine.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Gluten-Free Diet" – CeliacSociety.com

- ^ a b Akobeng AK, Thomas AG (2008). "Systematic review: tolerable amount of gluten for people with coeliac disease". Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 27 (11): 1044–52. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03669.x. PMID 18315587.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Pat Kendall, Ph.D., R.D. (March 31, 2003). "Gluten sensitivity more widespread than previously thought". Colorado State University Extension.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Following a Gluten-free Diet". Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. A Harvard teaching hospital.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ American Dietetic Association: Hot topics: gluten-free diets www.eatright.org/search.aspx? Dec. 2009

- ^ [1][dead link]

- ^ Journal of the American Dietetic Association. June 2010;939

- ^ Codex Alimentarius (2003) Draft revised standards for gluten-free foods, report of the 25th session of the Codex Committee on Nutrition and Foods for Special Dietary Uses, November 2003

- ^ Hischenhuber C, Crevel R, Jarry B, Makai M, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Romano A, Troncone R, Ward R (2006) Review article: safe amounts of gluten for patients with wheat allergy or coeliac disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 23(5):5590575

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.aca.2005.07.023, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.aca.2005.07.023instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 14744677, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=14744677instead. - ^ Ingredients "Gluten Free Living". Retrieved August 31, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Arentz-Hansen, Helene (October 19, 2004). "The Molecular Basis for Oat Intolerance in Patients with Coeliac Disease". PLoS Medicine. 1 (1). PLoS Medicine: e1. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0010001. PMC 523824. PMID 15526039. Retrieved July 22, 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Størsrud, S (May 7, 2002). "Adult celiac patients do tolerate large amounts of oats". European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 57 (1). doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601525. PMID 12548312. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Janatuinen, E K (May 1, 2002). "No harm from five year ingestion of oats in celiac disease". GUT Journal Online. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "The Scoop on Oats". Celiac Sprue Association (CSA). February 20, 2008.

- ^ Mohsid, Rashid (June 8, 2007). "Guidelines for Consumption of Pure and Uncontaminated Oats by Individuals with Coeliac Disease". Professional Advisory Board of Canadian Coeliac Association. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ^ "ADA Publishes Revised GF Diet Guidelines"

- ^ "Which alcoholic beverages are safe?" Celiac.com

- ^ StaVin Barrel Inserts Inc. [2] Retrieved May 18, 2009

- ^ Celiac.com, referencing a study from The Gluten-Free Dietician [3] Retrieved September 29, 2013

- ^ Simonato, Tolin, and Pasini, March 4, 2011 "Immunochemical and Mass Spectrometry Detection of Residual Proteins in Gluten Fined Red Wine," Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry [4]

- ^ "Is Beer Gluten-Free and Safe for People with Coeliac Disease?". Celiac.com. 2006. Archived from the original on May 13, 2006.

- ^ "Improved Methods for Determination of Beer Haze Protein Derived from Malt". Australian barley technical Symposium. Marian Sheehan A, Evan Evans B, and John Skerritt. 2001.

- ^ Livsmedelsverket. 2005 http://sverigesbryggerier.se/wp-content/uploads/2009/03/ol-ingredienser-gluteninnehall1.pdf.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Schober TJ, Bean SR. Gluten-free baking: what is happening inside the bread? USDA.

- ^ "Codex Standard For "Gluten-Free Foods" CODEX STAN 118-1981" (PDF). Codex Alimentarius. February 22, 2006.

- ^ "Gluten-free diets : Australian Institute of Sport : Australian Sports Commission". Ausport.gov.au. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ a b Spersud, Erik and Jennifer (January 3, 2008). Everything You Want To Know About Recipes And Restaurants And Much More. USA: Authorhouse. p. 172. doi:10.1007/b62130. ISBN 978-1-4343-6034-2.

- ^ "Sec. 184.1322 Wheat gluten". Code of Federal Regulations Center. April 1, 2007.

- ^ Schorr, Melissa (March 22, 2004). "Study: Wheat-Free Foods May Contain Wheat". WebMD.com. Archived from the original on March 14, 2008. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- ^ Roe, Sam. "Children at risk in food roulette". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ Roe, Sam. "Whole Foods pulls 'gluten-free' products from shelves after Tribune story". Chicagotribune.com. Retrieved September 20, 2009.

- ^ "Guidance Notes on the Food Labeling (Amendment)(No. 2) Regulations 2004" (PDF). Food Standards Agency. 2005.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "Labelling and Composition of Meat Products" (PDF). Food Standards Agency. April 22, 2004. Retrieved February 23, 2008.

- ^ "Food allergy guidance published". BBC News. January 16, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ Is chocolate gluten-free, Gluten free dark chocolate

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions". IPC Americas Inc. February 27, 2008. Archived from the original on April 11, 2008. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Excipient Ingredients in Medications". Gluten Free Drugs. November 3, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "Current Official Standards". FAO/WHO. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ a b "What is Gluten-Free? FDA Has an Answer". Food and Drug Administration. August 2, 2013. Retrieved August 2, 2013.

As one of the criteria for using the claim 'gluten-free,' FDA is setting a gluten limit of less than 20 ppm (parts per million) in foods that carry this label. This is the lowest level that can be consistently detected in foods using valid scientific analytical tools. Also, most people with celiac disease can tolerate foods with very small amounts of gluten. This level is consistent with those set by other countries and international bodies that set food safety standards.

- ^ Section 206 of the Food Allergen Labeling and Consumer Protection Act of 2004, Title II of Pub. L. 108–282 (text) (PDF), 118 Stat. 891 , enacted August 2, 2004

- ^ 72 FR 2795-2817

- ^ July 31, 2012, 5: 13 PM (July 31, 2012). "Gluten-free diet fad: Are celiac disease rates actually rising?". CBS News. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Gluten-Free, Whether You Need It or Not. NYTimes.

- ^ "Elsevier". Andjrnl.org. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

- ^ Oct. 18, 2012 Sarah Auffret, Arizona State University (October 18, 2012). "Gluten-free fad not backed by science | Management content from". Western Farm Press. Retrieved December 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Jonas F Ludvigsson (February 16, 2012). "The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms" (PDF). Gut. 62 (1). BMJ and British Society of Gastroenterology: 43–52. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346. Retrieved February 5, 2013.

CD was defined as 'a chronic small intestinal immune-mediated enteropathy precipitated by exposure to dietary gluten in genetically predisposed individuals'. Classical CD was defined as 'CD presenting with signs and symptoms of malabsorption. Diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, weight loss or growth failure is required.' 'Gluten-related disorders' is the suggested umbrella term for all diseases triggered by gluten and the term gluten intolerance should not to be used. Other definitions are presented in the paper.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Millward C, Ferriter M, Calver S, Connell-Jones G (2008). Ferriter, Michael (ed.). "Gluten- and casein-free diets for autistic spectrum disorder". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2): CD003498. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003498.pub3. PMID 18425890.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Popular Autism Diet Does Not Demonstrate Behavioral Improvement".

- ^ "Side Effects of the Gluten-Free Diet". about.com. 2009.

- ^

Lee AR, Ng DL, Dave E, Ciaccio J, Green PHR (2009). "The effect of substituting alternative grains in the diet on the nutritional profile of the gluten-free diet". Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics. 22 (4): 359–363. doi:10.1111/j.1365-277X.2009.00970.x. PMID 19519750.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ejcn.2009.113, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ejcn.2009.113instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2622422, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2622422instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19034261, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19034261instead.

External links

- Celiac Sprue Association: Gluten-Free Diet Self-Management and Basic Diet Choices

- Information on Gluten-Free Diet & Gluten Analysis in Food

- Gluten Intolerance Group Frequently asked questions

- Gluten Free WorldWide International gluten-free food directory

- Gluten Is The Devil Foods Containing Gluten