Spanish phonology

This article is about the phonology and phonetics of the Spanish language. Unless otherwise noted, statements refer to Castilian Spanish, the standard dialect used in Spain on radio and television.[1][2][3][4] For historical development of the sound system see History of Spanish. For details of geographical variation see Spanish dialects and varieties.

Spanish has many allophones, so it is important here to distinguish phonemes (written between slashes / /) and corresponding allophones (written between brackets [ ]).

Consonants

| Labial | Dental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | |||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | ʝ | k | ɡ | ||

| Continuant | f | θ* | s | (ʃ) | x | |||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ* | ||||||||

| Flap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

The phonemes /b/, /d/, and /ɡ/ are realized as approximants (namely [β̞, ð̞, ɣ̞], hereafter represented without the undertack) or fricatives[6] in all places except after a pause, after a nasal consonant, or—in the case of /d/—after a lateral consonant; in such contexts they are realized as voiced stops.[7] Some examples would be: hacia Bogotá [aθja βo̞ɣo̞ˈta] ('towards Bogota'), el búho [e̞l ˈβu.o̞] ('the owl'), and el delfín [e̞l de̞lˈfin] ('the dolphin').

The phoneme /ʝ/ is realized as an approximant in all contexts except after a pause, a nasal, or a lateral. In these environments, it may be realized as an affricate ([ɟʝ]).[8][9] The approximant allophone differs from non-syllabic /i/ in a number of ways; it has a lower F2 amplitude, is longer, can only appear in the syllable onset (including word-initially, where non-syllabic /i/ normally never appears), is a palatal fricative in emphatic pronunciations, and is unspecified for rounding (e.g. viuda [ˈbjuða] 'widow' vs ayuda [aˈʝʷuða] 'help').[10] The two also overlap in distribution after /l/ and /n/: enyesar [ẽ̞ɲɟʝe̞ˈsaɾ] ('to plaster') aniego [aˈnje̞ɣo̞] ('flood').[9] Although there is dialectal and ideolectal variation, speakers may also exhibit other near-minimal pairs like abyecto ('abject') vs abierto ('opened').[11][12] There are some alternations between the two, prompting scholars like Alarcos Llorach (1950)[13] to postulate an archiphoneme /I/, so that ley [lei̯] would be transcribed phonemically as /ˈleI/ and leyes [ˈleʝes] as /ˈleIes/.

In a number of varieties, including some American ones, a process parallel to the one distinguishing non-syllabic /i/ from consonantal /ʝ/ occurs for non-syllabic /u/ and a rare consonantal /w̝/.[9][14] Near-minimal pairs include deshuesar [de̞zw̝e̞ˈsaɾ] ('to bone') vs. desuello [de̞ˈswe̞ʎo̞] ('skinning'), son huevos [ˈsõ̞ŋ ˈw̝e̞βo̞s] ('they are eggs') vs son nuevos [ˈsõ̞ ˈnwe̞βo̞s] ('they are new'),[15] and huaca [ˈ(ɡ)w̝aka] ('Indian grave') vs u oca [ˈwo̞ka] ('or goose').[16]

The phoneme /ʎ/ (as distinct from /ʝ/) is found in some areas in Spain (mostly northern and rural) and some areas of South America (mostly highlands).

Most speakers in Spain (except for Western Andalusia and all Canary Islands), including the variety prevalent on radio and television, have both /θ/ and /s/ (distinción). However, speakers in Latin America and those parts of southern Spain have only /s/ (seseo). Some speakers in southernmost Spain (especially coastal Andalusia) have only [s̄] (a consonant similar to /θ/) and not /s/ (ceceo). This "ceceo" is not entirely unknown in the Americas, especially in coastal Peru. The phoneme /s/ has three different pronunciations ("laminal s", "apical s" or "apical dental s") depending on dialect.

The phonemes /t/ and /d/ are laminal denti-alveolars ([t̪, d̪]).[7] The phoneme /s/ becomes dental [s̪] before denti-alveolar consonants,[8] while /θ/ remains interdental [θ̟] in all contexts.[8]

According to some authors,[17] /x/ is post-velar or uvular in the Spanish of northern and central Spain.[18][19][20][21] Others[22] describe /x/ as velar in European Spanish, a uvular allophone ([χ]) appearing before /u/ (including when /u/ is in the syllable onset as [w]).[8]

A common pronunciation of /f/ in nonstandard speech is the voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ], so that fuera is pronounced [ˈɸweɾa] rather than [ˈfweɾa].[23] In some varieties (such as certain varieties of Honduran Spanish), this can lead to near-mergers in some word pairs[citation needed] (e.g. fuego [ˈɸweɣo] 'fire' v. juego [x̞ʷweɣo] 'game').

/ʃ/ is a marginal phoneme that only occurs in loanwords, in many dialects there is a tendency to substitute /tʃ/ or /s/ for it. In a number of dialects (most notably, Northern Mexican Spanish, informal Chilean Spanish, and some Caribbean and Andalusian accents) [ʃ] occurs, as a deaffricated /tʃ/.[23]

Consonant neutralizations

Some of the phonemic contrasts between consonants in Spanish are lost in certain phonological environments, and especially in syllable-final position. In these cases the phonemic contrast is said to be neutralized.

Sonorants

- Nasals and laterals

The three nasal phonemes—/m/, /n/, and /ɲ/—maintain their contrast when in syllable-initial position (e.g. cama 'bed', cana 'grey hair', caña 'sugar cane'). In syllable-final position, this three-way contrast is lost as nasals assimilate to the place of articulation of the following consonant[8]—even across a word boundary;[24] or, if a nasal is followed by a pause rather than a consonant, it is realized for most speakers as alveolar [n] (though in Caribbean varieties this may instead be [ŋ] or an omitted nasal with nasalization of the preceding vowel).[25][26] Thus /n/ is realized as [m] before labial consonants, and as [ŋ] before velar ones.

Similarly, /l/ assimilates to the place of articulation of a following coronal consonant, i.e. a consonant that is interdental, dental, alveolar, or palatal.[27][28][29]

Assimilatory nasal and lateral allophones are shown in the following table:

| nasal | lateral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | IPA | gloss | word | IPA | gloss |

| ánfora | [ˈãɱfo̞ɾa] | 'amphora' | |||

| encía | [ẽ̞n̟ˈθi.a] | 'gum' | alzar | [al̟ˈθaɾ] | 'to raise' |

| antes | [ˈãn̪t̪e̞s] | 'before' | alto | [ˈal̪t̪o̞] | 'tall' |

| ancha | [ˈãnʲtʃa] | 'wide' | colcha | [ˈko̞lʲtʃa] | 'quilt' |

| cónyuge | [ˈkõ̞ɲɟʝuxe̞] | 'spouse' | |||

| rincón | [rĩŋˈkõ̞n] | 'corner' | |||

| enjuto | [ẽ̞ɴˈχut̪o̞] | 'thin' | |||

- Rhotics

The alveolar trill [r] and the alveolar tap [ɾ] are in phonemic contrast word-internally between vowels (as in carro 'car' vs caro 'expensive'), but are otherwise in complementary distribution. Only the trill can occur after /l/, /n/, or /s/ (e.g. alrededor, enriquecer, Israel), and word-initially (e.g. rey 'king'). After a stop or fricative consonant, only the tap can occur (e.g. tres 'three', frío 'cold').

In syllable-final position, inside a word, the tap is more frequent, but the trill can also occur (especially in emphatic[30] or oratorical[31] style) with no semantic difference—thus arma ('weapon') may be either [ˈaɾma] (tap) or [ˈarma] (trill).[32]

In word-final position the rhotic will usually be;

- either a trill or a tap when followed by a consonant or a pause, as in amo[r ~ ɾ] paterno 'paternal love'),

- a tap when the followed by a vowel-initial word, as in amo[ɾ] eterno 'eternal love').

The tap/trill alternation has prompted a number of authors to postulate a single underlying rhotic; the intervocalic contrast then results from gemination (e.g. tierra /ˈtieɾɾa/ > [ˈtje̞ra] 'earth').[33][34][35]

Obstruents

The phonemes /θ/, /s/,[8] and /f/[36][37] become voiced before voiced consonants as in jazmín ('Jasmine') [xaðˈmĩn], rasgo ('feature') [ˈrazɣo̞], and Afganistán ('Afghanistan') [avɣanisˈtãn]. There is a certain amount of free variation in this so that jazmín can be pronounced [xaθˈmĩn] or [xaðˈmĩn].[38]

Both in casual and in formal speech, there is no phonemic contrast between voiced and voiceless consonants placed in syllable-final position. The merged phoneme is typically pronounced as a relaxed, voiced fricative or approximant,[39] although a variety of other realizations are also possible. So the clusters -bt- and -pt- in the words obtener and optimista are pronounced exactly the same way:

- obtener /obteˈner/ > [o̞βte̞ˈne̞r]

- optimista /obtiˈmista/ > [o̞βtiˈmista]

Similarly, the spellings -dm- and -tm- are merged in pronunciation, as well as -gd- and -cd-:

- adminículo /admiˈniculo/ > [aðmiˈnikulo̞]

- atmosférico /admosˈfeɾiko/ > [aðmo̞sˈfe̞ɾiko̞]

- amígdala /aˈmiɡdala/ > [aˈmiɣðala]

- anécdota /aˈneɡdota/ > [aˈne̞ɣðo̞ta]

Vowels

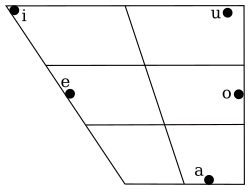

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Spanish has five vowels /i/, /e/, /a/, /o/ and /u/. Each occurs in both stressed and unstressed syllables:[40]

| stressed | unstressed | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| piso | 'I step' | pisó | 's/he stepped' |

| peso | 'I weigh' | pesó | 's/he weighed' |

| paso | 'I pass' | pasó | 's/he passed' |

| poso | 'I pose' | posó | 's/he posed' |

| pujo | 'I bid' (present tense) | pujó | 's/he bid' |

Nevertheless, there are some distributional gaps or rarities. For instance, an unstressed high vowel in the final syllable of a word is rare.[41]

- Allophones

Phonetic nasalization occurs for vowels occurring between nasal consonants or when preceding a syllable-final nasal, e.g. cinco [ˈsĩŋko̞] ('five').[40]

Arguably, Eastern Andalusian and Murcian Spanish have ten phonemic vowels, with each of the above vowels paired by a lowered (or fronted) and lengthened version, e.g. la madre [la ˈmaðɾe̞] 'the mother' vs. las madres [læ̞ː ˈmæ̞ːðɾɛː] 'the mothers'.[42] However, these are more commonly analyzed as allophones triggered by an underlying /s/ that is subsequently deleted.

Diphthongs and triphthongs

| IPA | Example | Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| Falling | ||

| /ei/ | rey | king |

| /ai/ | aire | air |

| /oi/ | hoy | today |

| /eu/ | neutro | neutral |

| /au/ | pausa | pause |

| /ou/[43] | bou | seine fishing |

| Rising | ||

| /je/ | tierra | earth |

| /ja/ | hacia | towards |

| /jo/ | radio | radio |

| /ju/ | viuda | widow |

| /wi/[44] | buitre | vulture |

| /we/ | fuego | fire |

| /wa/ | cuadro | picture |

| /wo/ | cuota | quota |

Spanish has six falling diphthongs and eight rising diphthongs. While many diphthongs are historically the result of a recategorization of vowel sequences (hiatus) as diphthongs, there is still lexical contrast between diphthongs and hiatus.[45] There are also some lexical items that vary amongst speakers and dialects between hiatus and diphthong: words like biólogo ('biologist') with a potential diphthong in the first syllable and words like diálogo with a stressed or pretonic sequence of /i/ and a vowel vary between a diphthong and hiatus.[46] Chițoran & Hualde (2007) hypothesize that this is because vocalic sequences are longer in these positions.

In addition to synalepha across word boundaries, sequences of vowels in hiatus become diphthongs in fast speech; when this happens, one vowel becomes non-syllabic (unless they are the same vowel, in which case they fuse together) as in poeta [ˈpo̯eta] ('poet') and maestro [ˈma̯estɾo̞] ('teacher').[47] Similarly, the relatively rare diphthong /eu/ may be reduced to [u] in certain unstressed contexts, as in Eufemia, [uˈfe̞mja].[48] In the case of verbs like aliviar ('relieve'), diphthongs result from the suffixation of normal verbal morphology onto a stem-final /j/ (that is, aliviar would be |alibj| + |ar|).[49] This contrasts with verbs like ampliar ('to extend') which, by their verbal morphology, seem to have stems ending in /i/.[50] Spanish also possesses triphthongs like /wei/ and, in dialects that use a second person plural conjugation, /jai/, /jei/, and /wai/ (e.g. buey, 'ox'; cambiáis, 'you change'; cambiéis, '(that) you may change'; and averiguáis, 'you ascertain').[51]

Non-syllabic /e/ and /o/ can be reduced to [ʝ], [w̝], as in beatitud [bʝatiˈtuð] ('beatitude') and poetisa [pw̝e̞ˈtisa] ('poetess'), respectively; similarly, non-syllabic /a/ can be completely elided, as in (e.g. ahorita [o̞ˈɾita] 'right away'). The frequency (though not the presence) of this phenomenon differs amongst dialects, with a number having it occur rarely and others exhibiting it always.[52]

Prosody

Spanish is usually considered a syllable-timed language. Even so, stressed syllables can be up to 50% longer in duration than non-stressed syllables.[53][54][55] Although pitch, duration, and loudness contribute to the perception of stress,[56] pitch is the most important in isolation.[57]

Primary stress occurs on the penultima (the next-to-last syllable) 80% of the time. The other 20% of the time, stress falls on the ultima and antepenultima (third-to-last syllable).[58]

Nonverbs are generally stressed on the penultimate syllable for vowel-final words and on the final syllable of consonant-final words. Exceptions are marked orthographically (see below), whereas regular words are underlyingly phonologically marked with a stress feature [+stress].[59]

In addition to exceptions to these tendencies, particularly learned words from Greek and Latin that feature antepenultimate stress, there are numerous minimal pairs which contrast solely on stress such as sábana ('sheet') and sabana ('savannah'), as well as límite ('boundary'), limite ('[that] he/she limit') and limité ('I limited').

Lexical stress may be marked orthographically with an acute accent (ácido, distinción, etc.). This is done according to the mandatory stress rules of Spanish orthography, which are similar to the tendencies above (differing with words like distinción) and are defined so as to unequivocally indicate where the stress lies in a given written word. An acute accent may also be used to differentiate homophones (such as té for 'tea' and te for 'you'). In such cases, the accent is used on the homophone that normally receives greater stress when used in a sentence.

Lexical stress patterns are different between words carrying verbal and nominal inflection: in addition to the occurrence of verbal affixes with stress (something absent in nominal inflection), underlying stress also differs in that it falls on the last syllable of the inflectional stem in verbal words while those of nominal words may have ultimate or penultimate stress.[60] In addition, amongst sequences of clitics suffixed to a verb, the rightmost clitic may receive secondary stress, e.g. búscalo /ˈbuskaˌlo/ ('look for it').[61]

Alternations

A number of alternations exist in Spanish that reflect diachronic changes in the language and arguably reflect morphophonological processes rather than strictly phonological ones. For instance, a number of words alternate between /k/ and /θ/ or /ɡ/ and /x/, with the latter in each pair appearing before a front vowel:[62]

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| opaco | /oˈpako/ | 'opaque' | opacidad | /opaθiˈdad/ | 'opacity' |

| sueco | /ˈsweko/ | 'Swedish' | Suecia | /ˈsweθja/ | 'Sweden' |

| belga | /ˈbelɡa/ | 'Belgian' | Bélgica | /ˈbelxika/ | 'Belgium' |

| análogo | /aˈnaloɡo/ | 'analogous' | analogía | /analoˈxia/ | 'analogy' |

Note that the conjugation of most verbs with a stem ending in /k/ or /ɡ/ does not show this alternation; these segments do not turn into /θ/ or /x/ before a front vowel:

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seco | /ˈseko/ | 'I dry' | seque | /ˈseke/ | '(that) I/he/she dry (subjunctive)' |

| castigo | /kasˈtiɡo/ | 'I punish' | castigue | /kasˈtiɡe/ | '(that) I/he/she punish (subjunctive)' |

There are also alternations between unstressed /e/ and /o/ and stressed /je/ and /we/ respectively:[63]

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| heló | /eˈlo/ | 'it froze' | hiela | /ˈʝela/ | 'it freezes' |

| tostó | /tosˈto/ | 'he toasted' | tuesto | /ˈtwesto/ | 'I toast' |

Likewise, in a very small number of words, alternations occur between the palatal sonorants /ʎ ɲ/ and their corresponding alveolar sonorants /l n/ (doncella/doncel 'maiden'/'youth', desdeñar/desdén 'to scorn'/'scorn'). This alternation does not appear in verbal or nominal inflection (that is, the plural of doncel is donceles, not *doncelles).[64] This is the result of geminated /ll/ and /nn/ of Vulgar Latin (the origin of /ʎ/ and /ɲ/, respectively) degeminating and then depalatalizing in coda position.[65] Words without any palatal-alveolar allomorphy are the result of historical borrowings.[65]

Other alternations include /ks/ ~ /x/ (anexo vs anejo),[66] /kt/ ~ /tʃ/ (nocturno vs noche).[67] Here the forms with /ks/ and /kt/ are historical borrowings and the forms with /x/ and /tʃ/ forms are inherited from Vulgar Latin.

There are also pairs that show antepenultimate stress in nouns and adjectives but penultimate stress in synonymous verbs (vómito 'vomit' vs. vomito 'I vomit').[68]

Phonotactics

Spanish syllable structure can be summarized as follows, in which parentheses enclose optional components:

- (C1 (C2)) (S1) V (S2) (C3 (C4))

Spanish syllable structure consists of an optional syllable onset, consisting of one or two consonants; an obligatory syllable nucleus, consisting of a vowel optionally preceded by and/or followed by a semivowel; and an optional syllable coda, consisting of one or two consonants. The following restrictions apply:

- Onset

- First consonant (C1): Can be any consonant, including a liquid (/l, r/).

- Second consonant (C2): If and only if the first consonant is a stop /p, t, k, b, d, ɡ/ or a voiceless labiodental fricative /f/, then a second consonant—which can only be a liquid /l, r/—is permitted. Although the onsets /tl/ and /dl/ do occur, they are not native to Spanish.

- Nucleus

- Semivowel (S1)

- Vowel (V)

- Semivowel (S2)

- Coda

- First consonant (C3): Can be any consonant.

- Second consonant (C4): Must be /s/. A coda combination of two consonants only appears in loanwords (mainly from Classical Latin), never in words inherited from Vulgar Latin.

- Medial codas assimilate place features of the following onsets and are often stressed.[69]

Examples of maximal onsets: transporte /transˈpor.te/, flaco /ˈfla.ko/, clave /ˈkla.be/

Examples of maximal nuclei: buey /buei/, Uruguay /u.ɾuˈɡuai/

Examples of maximal codas: instalar /ins.taˈlar/, perspectiva /pers.pekˈti.ba/

In many dialects, a coda can only be one consonant (one of n, r, l or s) in informal speech. So, realizations like /trasˈpor.te/, /is.taˈlar/, /pes.pekˈti.ba/ are very common, and in many cases they are considered legitimate even in formal speech.

Even in formal speech, /m/ is disallowed in word-final position, so a word such as Islam is regularly rendered as /isˈlan/.

Because of these phonotactic constraints, an epenthetic /e/ is inserted before word-initial cluster beginning with /s/ (e.g. escribir 'to write') but not word-internally (transcribir 'to transcribe'),[70] thereby moving the initial /s/ to a separate syllable. This epenthetic /e/ is pronounced even when it is not reflected in spelling (e.g. the surname of Carlos Slim is pronounced /esˈlin/). While Spanish words undergo word-initial epenthesis, cognates in Latin and Italian do not:

- Lat. status /ˈsta.tus/ ('state') ~ It. stato /ˈsta.to/ ~ Sp. estado /esˈta.do/

- Lat. splendidus /ˈsplen.di.dus/ ('splendid') ~ It. splendido /ˈsplen.di.do/ ~ Sp. espléndido /esˈplen.di.do/

- Fr. slave /slav/ ('Slav') ~ It. slavo /ˈsla.vo/ ~ Sp. eslavo /esˈla.bo/

Spanish syllable structure is phrasal, resulting in syllables consisting of phonemes from neighboring words in combination, sometimes even resulting in elision. This phenomenon is known in Spanish as enlace.[1] For a brief discussion contrasting Spanish and English syllable structure, see Whitley (2002:32–35).

Acquisition as a first language

Phonology

Phonological development varies greatly by individual, both those developing regularly and those with delays. However, a general pattern of acquisition of phonemes can be inferred by the level of complexity of their features, i.e. by sound classes.[71] A hierarchy may be constructed, and if a child is capable of producing a discrimination on one level, he/she will also be capable of making the discriminations of all prior levels.[72]

- The first level consists of stops (without a voicing distinction), nasals, [l], and optionally, a non-lateral approximant. This includes a labial/coronal place difference (for example, [b] vs [t] and [l] vs [β]).

- The second level includes voicing distinction for oral stops and a coronal/dorsal place difference. This allows for distinction between [p], [t], and [k], along with their voiced counterparts, as well as distinction between [l] and the approximant [j].

- The third level includes fricatives and/or affricates.

- The fourth level introduces liquids other than [l], [ɹ] and [ɾ]. It also introduces [θ].

- The fifth level introduces the trill [r].

This hierarchy is based on production only, and is a representation of a child’s capacity to produce a sound, whether that sound is the correct target in adult speech or not. Thus, it may contain some sounds that are not included in the adult phonology, but produced as a result of error.

Spanish-speaking children will accurately produce most segments at a relatively early age. By around three-and-a-half years, they will no longer productively use phonological processes the majority of the time. Some common error patterns (found 10% or more of the time) are cluster reduction, liquid simplification, and stopping. Less common patterns (evidenced less than 10% of the time) include palatal fronting, assimilation, and final consonant deletion.[73]

Typical phonological analyses of Spanish consider the consonants /b/, /d/, and /ɡ/ the underlying phonemes and their corresponding approximants [β], [ð], and [ɣ] allophonic and derivable by phonological rules. However, approximants may be the more basic form because monolingual Spanish-learning children learn to produce the continuant contrast between [p t k] and [β ð ɣ] before they do the lead voicing contrast between [p t k] and [b d ɡ].[74] (In comparison, English-learning children are able to produce adult-like voicing contrasts for these stops well before age three.)[75] The allophonic distribution of [b d ɡ] and [β ð ɣ] produced in adult speech is not learned until after age two and not fully mastered even at age four.[74]

The alveolar trill is one of the most difficult sounds to be produced in Spanish and as a result is acquired later in development.[76] Research suggests that the alveolar trill is acquired and developed between the ages of three and six years.[77] Some children acquire an adult-like trill within this period and some fail to properly acquire the trill. The attempted trill sound of the poor trillers is often perceived as a series of taps owing to hyperactive tongue movement during production.[78]

Codas

One research study found that children acquire medial codas before final codas, and stressed codas before unstressed codas.[79] Since medial codas are often stressed and must undergo place assimilation, greater importance is accorded to their acquisition.[69] Liquid and nasal codas occur word medially and at the ends of frequently-used function words, so they are often acquired first.[80]

Prosody

Research suggests that children overgeneralize stress rules when they are reproducing novel Spanish words and that they have a tendency to stress the penultimate syllables of antepenultimately stressed words, to avoid a violation of nonverb stress rules that they have acquired.[81] Many of the most frequent words heard by children have irregular stress patterns or are verbs, which violate nonverb stress rules.[82] This complicates stress rules until ages three to four, when stress acquisition is essentially complete, and children begin to apply these rules to novel irregular situations.

Dialectal variation

Some features, such as the pronunciation of voiceless stops /p t k/, have no dialectal variation.[83] However, there are numerous other features of pronunciation that differ from dialect to dialect.

Yeísmo

One notable dialectal feature is the merging of /ʝ/ and /ʎ/ into one phoneme (yeísmo); this was traditional in many peninsular (mainly southern) dialects. In recent times, it has spread to metropolitan areas in other parts of the Iberian Peninsula (such as Santander and Valladolid),[83] where /ʎ/ simply loses its laterality, and in some South American countries, where the phoneme resulting from the merger is realized as [ʒ].[8] In Buenos Aires, the sound has recently been devoiced to [ʃ] among the younger population, and the change is spreading throughout Argentina.[84]

Seseo, ceceo and distinción

Speakers in northern and central Spain, including the variety prevalent on radio and television, have both /θ/ and /s/ (distinción, 'distinction'). However, speakers in Latin America, Canary Islands and some parts of southern Spain have only /s/ (seseo), which in southernmost Spain is pronounced [θ] and not [s] (ceceo).[8]

Realization of /s/

The phoneme /s/ has three different pronunciations depending on the dialect area:[8][28][85]

- An apical alveolar retracted fricative (or "apico-alveolar" fricative) [s̺], sounding to some ears a bit like English /ʃ/. This is characteristic of the northern and central parts of Spain and is also used by many speakers in Colombia's Antioquia department.[86][87]

- A laminal alveolar grooved fricative [s], much like the most common pronunciation of English /s/. This is characteristic of western Andalusia (e.g. Málaga, Seville, and Cádiz), Canary Islands, and Latin America.

- An apical dental grooved fricative [s̄] (an ad-hoc symbol), which has a lisping quality and sounds something like a cross between English /s/ and /θ/ (but is not the same as the /θ/ occurring in ceceo dialects). It occurs in eastern Andalusia, for example in Granada, Huelva, Córdoba, Jaén and Almería.

Obaid describes the apico-alveolar sound as follows:[88]

- "There is a Castilian s, which is a voiceless, concave, apicoalveolar fricative: the tip of the tongue turned upward forms a narrow opening against the alveoli of the upper incisors. It resembles a faint /ʃ/ and is found throughout much of the northern half of Spain."

Dalbor describes the apico-dental sound as follows:[89]

- "[s̄] is a voiceless, corono-dentoalveolar groove fricative, the so-called s coronal or s plana because of the relatively flat shape of the tongue body.... To this writer, the coronal [s̄], heard throughout Andalusia, should be characterized by such terms as "soft," "fuzzy," or "imprecise," which, as we shall see, brings it quite close to one variety of /θ/ .... Canfield has referred, quite correctly, in our opinion, to this [s̄] as "the lisping coronal-dental," and Amado Alonso remarks how close it is to the post-dental [θ̦], suggesting a combined symbol [θṣ] to represent it."

In some dialects, /s/ may become the approximant [ɹ] in the syllable coda (e.g. doscientos [do̞ɹˈθjẽ̞n̪to̞s] 'two hundred').[90] In many places it debuccalizes to [h] in final position (e.g. niños [ˈnĩɲo̞h] 'children'), or before another consonant (e.g. fósforo [ˈfo̞hfo̞ɾo̞] 'match')—in other words, the change occurs in the coda position in a syllable.

From an autosegmental point of view, the /s/ phoneme in Madrid is defined only by its voiceless and fricative features. This means that the point of articulation is not defined and is determined from the sounds following it in the word or sentence. Thus in Madrid the following realizations are found: /pesˈkado/ > [pe̞xˈkao̞] and /ˈfosfoɾo/ > [ˈfo̞fːo̞ɾo̞]. In parts of southern Spain, the only feature defined for /s/ appears to be voiceless;[91] it may lose its oral articulation entirely to become [h], or even a geminate with the following consonant ([ˈmihmo̞] or [ˈmĩmːo̞] from /ˈmismo/ 'same').[92] In Eastern Andalusian and Murcian Spanish, word-final /s/, /θ/ and /x/ (phonetically [h]) regularly weaken, and the preceding vowel is lowered and lengthened:[42]

- /is/ > [i̞ː] e.g. mis [mi̞ː] ('my' pl)

- /es/ > [ɛː] e.g. mes [mɛː] ('month')

- /as/ > [æ̞ː] e.g. más [mæ̞ː] ('plus')

- /os/ > [ɔː] e.g. tos [tɔː] ('cough')

- /us/ > [u̞ː] e.g. tus [tu̞ː] ('your' pl)

A subsequent process of vowel harmony takes place so that lejos ('far') is [ˈlɛxɔ], tenéis ('you all have') is [tɛˈnɛi] and tréboles ('clovers') is [ˈtɾɛβɔlɛ] or [ˈtɾɛβo̞lɛ].[93]

Coda simplification

Southern European Spanish (i.e. Andalusian Spanish, Murcian Spanish, etc.) and several lowland dialects in Latin America (such as those from the Caribbean, Panama, and the Atlantic coast of Colombia) exhibit more extreme forms of simplification of coda consonants:

- word-final dropping of /s/ (e.g. compás [kõ̞mˈpa] 'musical beat' or 'compass')

- word-final dropping of nasals with nasalization of the preceding vowel (e.g. ven [bẽ̞] 'come')

- /r/ in the infinitival morpheme (e.g. comer [ko̞ˈme̞] 'to eat')

- the occasional dropping of coda consonants word-internally (e.g. doctor [do̞ˈto̞(r)] 'doctor').[94]

These dropped consonants do appear when additional suffixation occurs (e.g. compases [kõ̞mˈpase̞] 'beats', venían [be̞ˈni.ã] 'they were coming', comeremos [ko̞me̞ˈɾe̞mo̞] 'we will eat'). Similarly, a number of coda assimilations occur:

- /l/ and /r/ may neutralize to [j] (e.g. Cibaeño Dominican celda/cerda [ˈse̞jða] 'cell'/'bristle'), to [l] (e.g. Caribbean Spanish alma/arma [ˈalma] 'soul'/'weapon', Andalusian Spanish sartén [salˈtẽ]), to [r] (e.g. Andalusian Spanish alma/arma [ˈarma]) or, by complete regressive assimilation, to a copy of the following consonant (e.g. pulga/purga [ˈpuɡːa] 'flea'/'purge', carne [ˈkãnːe̞] 'meat').[94]

- /s/, /x/, (and /θ/ in southern Peninsular Spanish) and /f/ may be debuccalized or elided in the coda (e.g. los amigos [lo̞(h) aˈmiɣo̞(h)] 'the friends').[95]

- Stops and nasals may be realized as velar (e.g. Cuban and Venezuelan étnico [ˈe̞ɡniko̞] 'ethnic', himno [ˈĩŋno̞]).[95]

Notice that final /d/ dropping (e.g. mitad [miˈta] 'half') is general in most dialects of Spanish, even in formal speech.[citation needed]

These deletions and neutralizations show variability in their occurrence, even with the same speaker in the same utterance, implying that nondeleted forms exist in the underlying structure.[96] This doesn't mean that these dialects are on the path to eliminating coda consonants, since these processes have existed for more than four centuries in these dialects.[97] Guitart (1997) argues that this is the result of speakers acquiring multiple phonological systems with uneven control similar to that of second language learners.

In Standard European Spanish, voiced obstruents are devoiced before a pause as in [se̞ð̥] ('thirst').[98]

Loan sounds

The fricative /ʃ/ may also appear in borrowings from other languages like Nahuatl[99] and English.[100] In addition, the affricates /ts/ and /tɬ/ also occur in Nahuatl borrowings.[99]

See also

- History of the Spanish language

- List of phonetics topics

- Spanish dialects and varieties

- Stress in Spanish

Notes

- ^ Random House Unabridged Dictionary, Random House Inc., 2006

- ^ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.), Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006

- ^ Webster's Revised Unabridged Dictionary, MICRA, Inc., 1998

- ^ Encarta World English Dictionary. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. 2007. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ^ Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003:255)

- ^ The continuant allophones of Spanish /b, d, ɡ/ have been traditionally described as voiced fricatives (e.g. Navarro Tomás & 1918/1982, who (in §100) describes the air friction of [ð] as being "tenue y suave" ('weak and smooth'); Harris (1969); Dalbor & 1969/1997; and Macpherson (1975:62), who describes [β] as being "...with audible friction"). However, they are more often described as approximants in recent literature, such as D'Introno, Del Teso & Weston (1995); Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003); and Hualde (2005:43). The difference hinges primarily on air turbulence caused by extreme narrowing of the opening between articulators, which is present in fricatives and absent in approximants. Martínez-Celdrán (2004) displays a sound spectrogram of the Spanish word abogado showing an absence of turbulence for all three consonants.

- ^ a b Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003:257)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003:258)

- ^ a b c Trager (1942:222)

- ^ Martínez-Celdrán (2004:208)

- ^ Saporta (1956:288)

- ^ Bowen & Stockwell (1955:236) cite the minimal pair ya visto [(ɟ)ʝa ˈβisto̞] ('I already dress') vs y ha visto [ja ˈβisto̞] ('and he has seen')

- ^ cited in Saporta (1956:289)

- ^ Generally /w̝/ is [ɣʷ] though it may also be [βˠ] (Ohala & Lorentz (1977:590) citing Navarro Tomás (1961) and Harris (1969)).

- ^ Saporta (1956:289)

- ^ Bowen & Stockwell (1955:236)

- ^ For example Chen (2007), Hamond (2001) and Lyons (1981)

- ^ Chen (2007:13)

- ^ Hamond (2001:?), cited in Scipione & Sayahi (2005:128)

- ^ Harris & Vincent (1988:83)

- ^ Lyons (1981:76)

- ^ such as Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003)

- ^ a b Cotton & Sharp (1988:15)

- ^ Cressey (1978:61)

- ^ MacDonald (1989:219)

- ^ Lipski (1994:?) harvcoltxt error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFLipski1994 (help)

- ^ Navarro Tomás & 1918/1982:§111)

- ^ a b Dalbor (1980)

- ^ D'Introno, Del Teso & Weston (1995:118–121)

- ^ D'Introno, Del Teso & Weston (1995:294)

- ^ Canfield (1981:13)

- ^ Harris (1969:56)

- ^ Bowen, Stockwell & Silva-Fuenzalida (1956)

- ^ Harris (1969)

- ^ Bonet & Mascaró (1997)

- ^ Harris (1969:37 n.)

- ^ D'Introno, Del Teso & Weston (1995:289)

- ^ Cotton & Sharp (1988:19)

- ^ Navarro Tomás & 1918/1982, §98, §125)

- ^ a b c Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003:256)

- ^ Harris (1969:78, 145). Examples include words of Greek origin like énfasis ('emphasis'); the clitics su, tu, mi; the three Latin words espíritu ('spirit'), tribu ('tribe'), and ímpetu ('impetus'); and affective words like mami and papi.

- ^ a b Zamora Vicente (1967:?)

- ^ /ou/ occurs rarely in words; another example is the proper name Bousoño (Saporta 1956, p. 290). It is, however, common across word boundaries as with tengo una casa ('I have a house').

- ^ Harris (1969:89) points to muy ('very') as the one example with [ui̯] rather than [wi]. There are also a handful of proper nouns with [ui̯], exclusive to Chuy (a nickname) and Ruy. There are no minimal pairs.

- ^ Chițoran & Hualde (2007:45)

- ^ Chițoran & Hualde (2007:46)

- ^ Martínez-Celdrán, Fernández-Planas & Carrera-Sabaté (2003:256–257)

- ^ Cotton & Sharp (1988:18)

- ^ Harris (1969:99–101).

- ^ See Harris (1969:147–148) for a more extensive list of verb stems ending in both high vowels, as well as their corresponding semivowels.

- ^ Saporta (1956:290)

- ^ Bowen & Stockwell (1955:237)

- ^ Navarro Tomás (1916)

- ^ Navarro Tomás (1917)

- ^ Quilis (1971)

- ^ Cotton & Sharp (1988:19–20)

- ^ García-Bellido (1997:492), citing Contreras (1963), Quilis (1971), and the Esbozo de una nueva gramática de la lengua española. (1973) by the Gramática de la Real Acedemia Española

- ^ Lleó (2003:262)

- ^ Hochberg (1988:684)

- ^ García-Bellido (1997:473–474)

- ^ García-Bellido (1997:486), citing Navarro Tomás (1917:381–382, 385)

- ^ Harris (1969:79)

- ^ Harris (1969:26–27)

- ^ Pensado (1997:595–597)

- ^ a b Pensado (1997:608)

- ^ Harris (1969:188)

- ^ Harris (1969:189)

- ^ Harris (1969:97)

- ^ a b Lleó (2003:278)

- ^ Cressey (1978:86)

- ^ Cataño, Barlow & Moyna (2009:456)

- ^ Cataño, Barlow & Moyna (2009:448)

- ^ Goldstein & Iglesias (1998:5–6)

- ^ a b Macken & Barton (1980b:455)

- ^ Macken & Barton (1980b:73)

- ^ Carballo & Mendoza (2000:588)

- ^ Carballo & Mendoza (2000:589)

- ^ Carballo & Mendoza (2000:596)

- ^ Lleó (2003:271)

- ^ Lleó (2003:279)

- ^ Hochberg (1988:683)

- ^ Hochberg (1988:685)

- ^ a b Cotton & Sharp (1988:55)

- ^ Lipski, John (1994). Latin American Spanish. New York: Longman Publishing. p. 170.

- ^ Obaid (1973)

- ^ Flórez (1957:41)

- ^ Canfield (1981:36)

- ^ Obaid (1973).

- ^ Dalbor (1980).

- ^ Recasens (2004:436) citing Fougeron (1999) and Browman & Goldstein (1995)

- ^ Isogloss map for s aspiration in the Iberian Peninsula

- ^ Obaid (1973:62)

- ^ Lloret (2007:24–25)

- ^ a b Guitart (1997:515)

- ^ a b Guitart (1997:517)

- ^ Guitart (1997:515, 517–518)

- ^ Guitart (1997:518, 527), citing Boyd-Bowman (1975) and Labov (1994:595)

- ^ Wetzels & Mascaró (2001:224) citing Navarro Tomás (1961)

- ^ a b Lope Blanch (2004:29)

- ^ Ávila (2003:67)

References

- Abercrombie, David (1967), Elements of General Phonetics, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press

- Alarcos Llorach, Emilio (1950), Fonología Española, Madrid: Gredos

- Ávila, Raúl (2003), "La pronunciación del español: medios de difusión masiva y norma culta", Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica, 51 (1): 57–79

- Bonet, Eulàlia; Mascaró, Joan (1997), "On the representation of contrasting rhotics", in Martínez-Gil, Fernando; Morales-Front, Alfonso (eds.), Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages, Georgetown University Press, pp. 103–126

{{citation}}: Missing|editor2=(help) - Bowen, J. Donald; Stockwell, Robert P. (1955), "The Phonemic Interpretation of Semivowels in Spanish", Language, 31 (2), Linguistic Society of America: 236–240, doi:10.2307/411039, JSTOR 411039

- Bowen, J. Donald; Stockwell, Robert P.; Silva-Fuenzalida, Ismael (1956), "Spanish juncture and intonation", Language, 32 (4): 641–665, doi:10.2307/411088, JSTOR 411088

- Boyd-Bowman, Peter (1975), "A sample of Sixteenth Century 'Caribbean' Spanish Phonology.", in Milán, William; Zamora, Juan C.; Staczek, John J. (eds.), 1974 Colloquium on Spanish and Portuguese Linguistics, Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, pp. 1–11

- Browman, L.; Goldstein (1995), "Gestural syllable position in American English", in Bell-Berti, F.; Raphael, L.J. (eds.), Producing Speech: Contemporary issues for K Harris, New York: AIP, pp. 9–33

{{citation}}: Missing|editor2=(help) - Canfield, D. Lincoln (1981), Spanish Pronunciation in the Americas, Chicago: University of Chicago Press

- Carballo, Gloria; Mendoza, Elvira (2000), "Acoustic characteristics of trill productions by groups of Spanish children", Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 14 (8): 587–601, doi:10.1080/026992000750048125

- Cataño, Lorena; Barlow, Jessica A.; Moyna, María Irene (2009), "A retrospective study of phonetic inventory complexity in acquisition of Spanish: Implications for phonological universals", Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 23 (6): 446–472, doi:10.1080/02699200902839818

- Chen, Yudong (2007), A Comparison of Spanish Produced by Chinese L2 Learners and Native Speakers---an Acoustic Phonetics Approach, ISBN 9780549464037

- Chițoran, Ioana; Hualde, José Ignacio (2007), "From hiatus to diphthong: the evolution of vowel sequences in Romance", Phonology, 24: 37–75, doi:10.1017/S095267570700111X

- Contreras, Heles (1963), "Sobre el acento en español.", Boletín de Filología, 15, Universidad de Santiago de Chile: 223–237

- Cotton, Eleanor Greet; Sharp, John (1988), Spanish in the Americas, Georgetown University Press, ISBN 978-0-87840-094-2

- Cressey, William Whitney (1978), Spanish Phonology and Morphology: A Generative View, Georgetown University Press, ISBN 978-0-87840-045-4

- Dalbor, John B. (1969/1997), Spanish Pronunciation: Theory and Practice: An Introductory Manual of Spanish Phonology and Remedial Drill (3rd ed.), Fort Worth: Holt, Rinehart and Winston

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Dalbor, John B. (1980), "Observations on Present-Day Seseo and Ceceo in Southern Spain", Hispania, 63 (1), American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese: 5–19, doi:10.2307/340806, JSTOR 340806

- D'Introno, Francesco; Del Teso, Enrique; Weston, Rosemary (1995), Fonética y fonología actual del español, Madrid: Cátedra

- Eddington, David (2000), "Spanish Stress Assignment within the Analogical Modeling of Language" (PDF), Language, 76 (1), Linguistic Society of America: 92–109, doi:10.2307/417394, JSTOR 417394

- Flórez, Luis (1957), Habla y cultura popular en Antioquia, Bogotá: Instituto Caro y Cuervo

- Fougeron, C (1999), "Prosodically conditioned articulatory variation: A Review", UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics, vol. 97, pp. 1–73

- García-Bellido, Paloma (1997), "The interface between inherent and structural prominence in Spanish", in Martínez-Gil, Fernando; Morales-Front, Alfonso (eds.), Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages, Georgetown University Press, pp. 469–511

{{citation}}: Missing|editor2=(help) - Goldstein, Brian A.; Iglesias, Aquiles (1998), Phonological Production in Spanish-Speaking Preschoolers

- Guitart, Jorge M. (1997), "Variability, multilectalism, and the organization of phonology in Caribbean Spanish dialects", in Martínez-Gil, Fernando; Morales-Front, Alfonso (eds.), Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages, Georgetown University Press, pp. 515–536

{{citation}}: Missing|editor2=(help) - Hamond, Robert M. (2001), The Sounds of Spanish: Analysis and Application, Cascadilla Press, ISBN 978-1-57473-018-0

- Harris, James (1969), Spanish phonology, Cambridge: MIT Press

- Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (1988), "Spanish", The Romance Languages, pp. 79–130, ISBN 0-415-16417-6

- Hochberg, Judith G. (1988), "Learning Spanish Stress: Developmental and Theoretical Perspectives", Language, 64 (4): 683–706, JSTOR 414564

- Hualde, José Ignacio (2005), The Sounds of Spanish, Cambridge University Press

- Labov, William (1994), Principles of Linguistic Change: Volume I: Internal Factors, Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers

- Ladefoged, Peter; Johnson, Keith (2010), A Course in Phonetics (6th ed.), Boston, Massachusetts: Wadsworth Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4282-3126-9

- Lipski, John M. (1994), Latin American Spanish, London: Longman

- Lipski, John M. (1990), Spanish taps and trills: Phonological structure of an isolated position

- Lleó, Conxita (2003), "Prosodic licensing of codas in the acquisition of Spanish", Probus, 15 (2): 257–281, doi:10.1515/prbs.2003.010

- Lloret, Maria-Rosa (2007), "On the Nature of Vowel Harmony: Spreading with a Purpose", in Bisetto, Antonietta; Barbieri, Francesco (eds.), Proceedings of the XXXIII Incontro di Grammatica Generativa, pp. 15–35

- Lope Blanch, Juan M. (2004), Cuestiones de filología mexicana, Mexico: editorial Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, ISBN 978-970-32-0976-7

- Lyons, John (1981), Language and Linguistics: An Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-54088-9

- MacDonald, Marguerite (1989), "The influence of Spanish phonology on the English spoken by United States Hispanics", in Bjarkman, Peter; Hammond, Robert (eds.), American Spanish pronunciation: Theoretical and applied perspectives, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, pp. 215–236, ISBN 9780878404933

- Macken, Marlys A.; Barton, David (1980a), "The acquisition of the voicing contrast in English: a study of voice onset time in word-initial stop consonants", Journal of Child Language, 7 (1): 41–74, doi:10.1017/S0305000900007029

- Macken, Marlys A.; Barton, David (1980b), "The acquisition of the voicing contrast in Spanish: a phonetic and phonological study of word-initial stop consonants", Journal of Child Language, 7 (3): 433–458, doi:10.1017/S0305000900002774, PMID 6969264

- Macpherson, Ian R. (1975), Spanish Phonology: Descriptive and Historical., Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-0788-0

- Martínez-Celdrán, Eugenio; Fernández-Planas, Ana Ma.; Carrera-Sabaté, Josefina (2003), "Castilian Spanish", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 33 (2): 255–259, doi:10.1017/S0025100303001373

- Martínez-Celdrán, Eugenio (2004), "Problems in the Classification of Approximants", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 34 (2): 201–210, doi:10.1017/S0025100304001732

- Navarro Tomás, Tomás (1916), "Cantidad de las vocales acentuadas", Revista de Filología Española, 3: 387–408

- Navarro Tomás, Tomás (1917), "Cantidad de las vocales inacentuadas", Revista de Filología Española, 4: 371–388

- Navarro Tomás, Tomás (1918/1982), Manual de pronunciación española (21st ed.), Madrid: CSIC

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: year (link) - Obaid, Antonio H. (1973), "The Vagaries of the Spanish 'S'", Hispania, 56 (1), American Association of Teachers of Spanish and Portuguese: 60–67, doi:10.2307/339038, JSTOR 339038

- Ohala, John; Lorentz, James (1977), "The story of [w]: An exercise in the phonetic explanation for sound patterns", in Whistler, Kenneth; Chiarelloet, Chris; van Vahn, Robert Jr. (eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistic Society, pp. 577–599

- Pensado, Carmen (1997), "On the Spanish depalatalization of /ɲ/ and /ʎ/ in rhymes", in Martínez-Gil, Fernando; Morales-Front, Alfonso (eds.), Issues in the Phonology and Morphology of the Major Iberian Languages, Georgetown University Press, pp. 595–618

- Quilis, Antonio (1971), "Caracterización fonética del acento en español.", Travaux de Linguistique et de Littérature, 9: 53–72

- Recasens, Daniel (2004), "The effect of syllable position on consonant reduction (evidence from Catalan consonant clusters)", Journal of Phonetics, 32 (3): 435–453, doi:10.1016/j.wocn.2004.02.001

- Saporta, Sol (1956), "A Note on Spanish Semivowels", Language, 32 (2), Linguistic Society of America: 287–290, doi:10.2307/411006, JSTOR 411006

- Scipione, Ruth; Sayahi, Lotfi (2005), "Consonantal Variation of Spanish in Northern Morocco", in Sayahi, Lotfi; Westmoreland, Maurice (eds.), Selected Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Spanish Sociolinguistics (PDF), Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Proceedings Project

- Trager, George (1942), "The Phonemic Treatment of Semivowels", Language, 18 (3), Linguistic Society of America: 220–223, doi:10.2307/409556, JSTOR 409556

- Wetzels, W. Leo; Mascaró, Joan (2001), "The Typology of Voicing and Devoicing", Language, 77 (2): 207–244, doi:10.1353/lan.2001.0123

- Whitley, M. Stanley (2002), Spanish/English Contrasts: A Course in Spanish Linguistics (2nd ed.), Georgetown University Press, ISBN 978-0-87840-381-3

- Zamora Vicente, Alonso (1967), Dialectología española (2nd ed.), Biblioteca Romanica Hispanica, Editorial Gredos

Further reading

- Hammond, Robert M. (2001), The Sounds of Spanish: Analysis and Application, Somerville, Massachusetts: Cascadilla Press, ISBN 978-1-57473-018-0

- Otero, C. (1986), "A unified metrical account of Spanish stress.", in Brame, M.; Newmeyer, F.J.; Contreras, H. (eds.), A Festschrift for Sol Saporta, Seattle: Noit Amrofer, pp. 299–332

- Roca, Iggy (1990a), "Diachrony and synchrony in Spanish stress", Journal of Linguistics, 26: 133–164, doi:10.1017/s0022226700014456

- Roca, Iggy (1990b), "Morphology and verbal stress in Spanish", Probus, 2 (3): 321–50, doi:10.1515/prbs.1990.2.3.321

- Roca, Iggy (1992), "On the sources of word prosody", Phonology, 9 (2), Cambridge University Press: 267–287, doi:10.1017/S0952675700001615, JSTOR 4420057

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (September 2010) |

- Animations and video demonstrations of the IPA for Spanish by The Departments of Spanish and Portuguese, German, Speech Pathology and Audiology, and Academic Technologies at the University of Iowa.