Robert Owen

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2012) |

Robert Owen | |

|---|---|

Owen, aged about 50 | |

| Born | 14 May 1771 Newtown, Montgomeryshire, Wales |

| Died | 17 November 1858 (aged 87) Newtown, Montgomeryshire, Wales |

| Occupation(s) | Co-operator; social reformer, factory owner; inventor |

| Spouse | Caroline Dale |

| Children | Jackson Dale (1799) Robert Dale (1801) William (1802) Anne Caroline (1805) Jane Dale (1805) David Dale (1807) Richard Dale (1809) Mary Dale/Owen (1810) |

| Parent(s) | Robert Owen and Anne Williams[1] |

Robert Owen (/ˈoʊ[invalid input: 'ɨ']n/; 14 May 1771 – 17 November 1858) was a Welsh social reformer and one of the founders of utopian socialism and the cooperative movement. He worked in the cotton industry in Manchester before setting up a large mill at New Lanark in Scotland. In 1824, Owen travelled to America to invest the bulk of his fortune in an experimental 1,000-member colony on the banks of Indiana's Wabash River, called New Harmony. New Harmony was intended to be a Utopian society.

Biography

Early life

Robert Owen was born in Newtown a small market town in Montgomeryshire, Mid Wales, in 1771. He was the sixth of seven children. His father, also named Robert Owen, had a small business as a saddler and ironmonger. Owen's mother came from a prosperous farming family called Williams.[2] There Owen received almost all his school education, which ended at the age of ten. In 1787, after serving in a draper's shop for some years, he settled in London.

He moved to Manchester, and was employed at Satterfield's Drapery in St Ann's Square (a plaque currently marks the site[3]). With money borrowed from his brother he set up a workshop making spinning mules but exchanged the business for 6 spinning mules, which he operated in a rented space. In 1792 he was made manager of the Piccadilly Mill at Bank Top by the mill-owner Peter Drinkwater at the age of 21, but after two years he voluntarily gave up a contracted promise of partnership in the company and left to go into partnership instead with other entrepreneurs to establish and manage the Chorlton Twist Mills in Chorlton-on-Medlock.

His entrepreneurial spirit, management skill and progressive moral views were emerging by the early 1790s. In 1793, he was elected as a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, where the ideas of reformers and philosophers of the Enlightenment were discussed. He also became a committee member of the Manchester Board of Health which was instigated, principally by Thomas Percival, to promote improvements in the health and working conditions of factory workers.

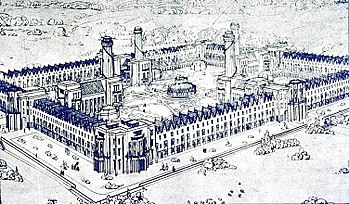

New Lanark Mill

During a visit to Scotland, Owen fell in love with Caroline Dale, the daughter of the New Lanark mill's proprietor David Dale. Owen convinced his partners to buy New Lanark, and after his marriage to Caroline[4] in September 1799, he made his home there. He was a manager and part-owner of the mills (January 1810). Encouraged by his success in the management of cotton mills in Manchester, he hoped to conduct New Lanark on higher principles than purely commercial ones.

The mill of New Lanark had been started in 1785 by David Dale and Richard Arkwright. The water power provided by the falls of the River Clyde made it a great attraction. About 2,000 people had associations with the mills, 500 of whom were children brought at the age of five or six from the poorhouses and charities of Edinburgh and Glasgow. The children were well treated by Dale, but the general condition of the people was unsatisfactory. Many of the workers were in the lowest levels of the population; theft, drunkenness, and other vices were common; education and sanitation were neglected; and most families lived in one room. The respectable country people refused to submit to the long hours and demoralising drudgery of the mills.

Many employers operated the truck system, and paid workers in part or totally by tokens. These tokens had no value outside the mill owner's "truck shop". The owners could supply shoddy goods to the truck shop and charge top prices. This abuse was stopped by a series of "Truck Acts" (1831–1887), making it an offence not to pay employees in common currency. Owen opened a store where the people could buy goods of sound quality at little more than wholesale cost, and he placed the sale of alcohol under strict supervision. He sold quality goods and passed on the savings from the bulk purchase of goods to the workers. These principles became the basis for the cooperative shops in Britain, which continue in an altered form to trade today.

Owen's greatest success was in support of the young. He can be considered as the founder of infant child care in Britain, especially Scotland. Although his reform ideas resembled those of European innovators of the time, he was probably not influenced by such overseas approaches; his ideas on ideal education were his own.[original research?]

Philosophy and influence

At first regarded with suspicion, Owen soon won the confidence of his workers. The mills continued to have great commercial success, but some of Owen's schemes were very expensive, which displeased his partners. Tired of the restrictions imposed on him by men who wanted to conduct the business on the ordinary principles, Owen arranged in 1813 to have them bought out by new investors. These, including Jeremy Bentham and the well-known Quaker William Allen, were content to accept just £5000 return on their capital, allowing Owen a freer scope for his philanthropy. In the same year, Owen authored several essays in which he expounded on the principles behind his education philosophy.

Owen had originally been a follower of the classical liberal and utilitarian Jeremy Bentham, who believed that free markets (and in particular, the right of workers to move and choose their employers) would free the workers from the excessive power of capitalists. Owen moved toward a more socialist outlook. At an early age, he had lost faith in the prevailing religion and thought out a belief system of his own, which he considered a new and original discovery. The chief points were that human character is formed by circumstances over which individuals have no control, and so cannot be properly praised or blamed. These principles lead to the conclusion that the secret behind the correct formation of people's characters is to place them under proper influences – physical, moral and social – from their earliest years. The principles of the irresponsibility of man and of the effect of early influences are the key to Owen's system of education and social amelioration, embodied in his first work, A New View of Society, or Essays on the Principle of the Formation of the Human Character, the first of four essays to appear in 1813. Owen's views theoretically belong to a very old system of philosophy, and his originality is to be found only in his benevolent application of them.

For the next few years, Owen's work at New Lanark continued to have significance throughout Britain and even in continental Europe. His schemes for the education of his workers moved to something like completion on the opening of the institution at New Lanark in 1816. He zealously supported the factory legislation, culminating in the 1819 Cotton Mills and Factories Act. He had interviews and communications with the leading members of government, including the premier, Robert Banks Jenkinson, Lord Liverpool, and with many of the rulers and leading statesmen of Europe.

Owen also adopted new principles in raising the standard of goods produced. A cube with faces painted in different colors was installed above each machinist's workplace. The colour of the face showed to everyone the quality and quantity of work completed. This provided incentives to workers to do their best. Although not in itself a great incentive, the conditions at New Lanark for the workers and their families were idyllic for the time.

New Lanark became much visited by social reformers, statesmen, and royals, including the later Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. According to unanimous testimony from all who visited it, New Lanark appeared singularly good. The manners of the children brought up under his system were beautifully graceful, genial and unconstrained; health, plenty, and contentment prevailed; drunkenness was almost unknown; and illegitimacy extremely rare. Owen's relationship with the workers remained excellent, and all the operations of the mill proceeded with smoothness and regularity. Furthermore, the business was a commercial success.

Eight-hour day

Robert Owen raised the demand for a ten-hour day in 1810, and instituted it in his socialist enterprise at New Lanark. By 1817 he had formulated the goal of the eight-hour day and coined the slogan: "Eight hours labour, Eight hours recreation, Eight hours rest".

Models for socialism (1817)

Robert Owen was initially a philanthropist, but embraced socialism in 1817, with a report to the committee of the House of Commons on the Poor Law.

The misery and trade stagnation after the Napoleonic Wars was capturing the attention of the country. Although tracing the immediate causes of misery to the wars, Owen argued that the underlying cause of distress was the competition of human labour with machinery, and that the only effective remedy was the united action of men and the subordination of machinery. He proposed that communities of about 1,200 people should be settled on land from 1,000 to 1,500 acres (4 to 6 km2), all living in one large square building, with public kitchen and mess-rooms. Each family should have its own private apartments and the entire care of the children till age three, after which they should be brought up by the community; their parents would have access to them at meals, however, and at all other proper times.

These communities might be established by individuals, by parishes, by counties, or by the state; in every case, there should be effective supervision by duly qualified persons. Work, and the enjoyment of its results, should be experienced communally. The size of his community was no doubt partly suggested by his village of New Lanark; and he soon proceeded to advocate such a scheme as the best form for the re-organization of society in general.

Owen's model changed little during his life. His fully developed model was as follows. He considered an association of 500 to 3000 people as the fit number for a good working community. While mainly agricultural, it should possess all the best machinery, should offer every variety of employment, and should, as far as possible, be self-contained. "As these townships" (as he also called them) "should increase in number, unions of them federatively united shall be formed in circles of tens, hundreds and thousands", until they included the whole world in a common interest.

In Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race, Owen asserts and reasserts that character is formed by a combination of Nature or God and the circumstances of the individual's experience. Owen provides little real evaluation of the subject but agrees with Socrates' general overview.

Community experiments in America (1825)

| This article is part of a series on |

| Socialism in the United States |

|---|

|

In 1825, such an experiment was attempted under the direction of his disciple, Abram Combe, at Orbiston, Scotland near Glasgow; and the next year Owen himself began another at New Harmony, Indiana, US, sold to him by George Rapp. After a trial of about two years, both projects failed. Neither project was a proper experiment; their members were motley, mixing many worthy people of the highest aims with vagrants, adventurers, and crotchety, wrongheaded enthusiasts, or in the words of Owen's son "a heterogeneous collection of radicals, enthusiastic devotees to principle, honest latitudinarians, and lazy theorists, with a sprinkling of unprincipled sharpers thrown in."[5]

Josiah Warren, who was one of the participants in the New Harmony Society, asserted that community was doomed to failure due to a lack of individual sovereignty and personal property. He says of the community: "We had a world in miniature — we had enacted the French revolution over again with despairing hearts instead of corpses as a result. ... It appeared that it was nature's own inherent law of diversity that had conquered us ... our "united interests" were directly at war with the individualities of persons and circumstances and the instinct of self-preservation ..." (Periodical Letter II 1856) Warren's observations on the reasons for the community's failure led to the development of American individualist anarchism, of which he was its original theorist. The Forestville Commonwealth Owenite community at Earlton, New York was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[6]

London

After a long period of friction with William Allen and some of his other partners, Owen resigned all connection with New Lanark in 1828. His words to William Allen at the time are often quoted as being : "All the world is queer save thee and me, and even thou art a little queer".[7][8] On his return from America, he centred his activity in London. Having sunk most of his means in the New Harmony experiment, he was no longer a flourishing capitalist, but he remained the head of a vigorous propaganda machine, combining socialism and secularism. One of the most interesting features of the movement at this period was the establishment in 1832 of the National Equitable Labour Exchange system, a Time-based currency in which exchange was effected by means of labour notes; this system superseded the usual means of exchange and middlemen. The London exchange lasted until 1833, and a Birmingham branch operated for only a few months until July 1833.

The word "socialism" first became current in the discussions of the "Association of all Classes of all Nations" which Owen formed in 1835[9] with himself as Preliminary Father.[10] During these years his secularistic teaching gained such influence among the working classes as to give occasion for the statement in the Westminster Review (1839) that his principles were the actual creed of a great portion of them.

At this period, some more communist experiments were made, of which the most important were that at Ralahine, in County Clare, Ireland, and that at Tytherley in Hampshire. The former (1831) proved a remarkable success for three-and-a-half years until the proprietor, having ruined himself by gambling, had to sell out. Tytherley, begun in 1839, failed absolutely.

By 1846, the only permanent result of Owen's agitation, so zealously carried on by public meetings, pamphlets, periodicals, and occasional treatises remained the co-operative movement, and for a time even that seemed to have utterly collapsed. He died at his native town on 17 November 1858.

Role in spiritualism

In 1854, at the age of 83, and despite his previous antipathy to religion, Owen was converted to spiritualism after a series of "sittings" with the American medium Maria B. Hayden (credited with introducing spiritualism to England). Owen made a public profession of his new faith in his publication The Rational quarterly review and later wrote a pamphlet entitled The future of the Human race; or great glorious and future revolution to be effected through the agency of departed spirits of good and superior men and women.[11]

Owen claimed to have had mediumistic contact with the spirits of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and others, the purpose of whose communications was "to change the present, false, disunited and miserable state of human existence, for a true, united and happy state ... to prepare the world for universal peace, and to infuse into all the spirit of charity, forbearance and love."[12]

After Owen's death spiritualists claimed that his spirit dictated the "Seven Principles of Spiritualism" to the medium Emma Hardinge Britten in 1871.[13]

Children

Robert and Caroline Owen's first child died in infancy. They had seven surviving children, four sons and three daughters: Robert Dale (born 1801), William (1802), Anne Caroline (1805), Jane Dale (1805), David Dale (1807), Richard Dale (1809) and Mary (1810). Owen's four sons, Robert Dale, William, David Dale, and Richard, all became citizens of the United States. Anne Caroline and Mary (together with their mother, Caroline) died in the 1830s. Jane, the remaining daughter, joined her brothers in America, where she married Robert Henry Fauntleroy.

Robert Dale Owen, the eldest (1801–1877), was for long an able exponent in his adopted country of his father's doctrines. In 1836–1839 and 1851–1852 he served as a member of the Indiana House of Representatives and in 1844–1847 was a Representative in Congress, where he drafted the bill for the founding of the Smithsonian Institution. He was elected a member of the Indiana Constitutional Convention in 1850, and was instrumental in securing to widows and married women control of their property and the adoption of a common free school system. He later succeeded in passing a state law giving greater freedom in divorce. From 1853 to 1858, he was United States minister at Naples. He was a strong believer in spiritualism and was the author of two well-known books on the subject: Footfalls on the Boundary of Another World (1859) and The Debatable Land Between this World and the Next (1872).

Owen's third son, David Dale Owen (1807–1860), was in 1839 appointed a United States geologist who made extensive surveys of the north-west, which were published by order of Congress. The youngest son, Richard Dale Owen (1810–1890), was an American Civil War colonel and first president of Purdue University.

Works

- 1813. A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character, and the Application of the Principle to Practice. London. Retitled, A New View of Society: Or, Essays on the Formation of Human Character Preparatory to the Development of a Plan for Gradually Ameliorating the Condition of Mankind, for second edition, 1816

- 1815. Observations on the Effect of the Manufacturing System. 2nd edn, London.

- 1817. Report to the Committee for the Relief of the Manufacturing Poor. In The Life of Robert Owen written by Himself, 2 vols, London, 1857-67.

- 1818. Two memorials behalf of the working classes. In The Life of Robert Owen written by Himself, 2 vols, London, 1857-8.

- 1819. An Address to the Master Manufacturers of Great Britain. Bolton.

- 1821. Report to the County of Lanark of a Plan for relieving Public Distress. Glasgow: Glasgow University Press.

- 1823. An Explanation of the Cause of Distress which pervades the civilised parts of the world. London. & Paris.

- 1830. Was one of the founders of the Grand National Consolidated Trade Union (GNCTU)

- 1832. An Address to All Classes in the State. London.

- 1849. The Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race. London.

Robert Owen wrote numerous works about his system. Of these, the most notable are:

- the New View of Society

- the Report communicated to the Committee on the Poor Law

- the Book of the New Moral World

- Revolution in the Mind and Practice of the Human Race

- An accessible collection of Owen's best-known publications is A New View of Society and Other Writings, ed. G. Claeys (Penguin Books, 1991)

- Owen's major works are reprinted in The Selected Works of Robert Owen, ed. G. Claeys

(4 vols., London, Pickering and Chatto, 1993). The Robert Owen Collection, including papers and letters as well as pamphlets and books by and about him, is deposited with the National Co-operative Archive, UK.[14]

See also

- List of Owenite communities in the United States

- José María Arizmendiarrieta

- Labour voucher

- William King (doctor)

- Owenstown

- Owenism

References

- ^ "Robert Owen." Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2014. Web. 9 January 2014.

- ^ https://books.google.com/books?id=E-sJAAAAIAAJ&pg=PR18

- ^ [1]

- ^ Robert Owen Museum website. Accessed 26 February 2015

- ^ Robert Owen: Pioneer of Social Reforms by Joseph Clayton, 1908, A.C. Fifield, London

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 13 March 2009.

- ^ "1828: Information from". Answers.com. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ "Who said this: "all strange but thee and Me" – Literature Network Forums". Online-literature.com. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ Royle, Edward (1998) Robert Owen and the Commencement of the Millennium, Manchester University Press, ISBN 0-7190-5426-5 p.56

- ^ Harvey, Rowland Hill (1949) Robert Owen: Social Idealist, University of California Press, p.211

- ^ See Lewis Spence. Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology" (Kessinger Pub. Co., 2003), p679.

- ^ See Frank Podmore. Robert Owen, a biography – Vol. 2, p600ff.

- ^ History of Spiritualism (SNU international)

- ^ "National Co-operative Archive". Archive.co-op.ac.uk. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

Sources

Biographies

- Robert Owen. Life of Owen by himself (London, 1857)

- Robert Dale Owen. Threading my Way, Twenty-seven Years of Autobiography(London: Trubner & Co., 1874) – R. D. Owen was the son of Robert Owen.

There are also Lives of Owen by:

- A. J. Booth. Robert Owen, the Founder of Socialism in England (London, 1869)

- G. D. H. Cole. Life of Robert Owen (London, Ernest Benn Ltd., 1925)

- Lloyd Jones. The Life, Times, and Labours of Robert Owen (London, 1889).

- A. L. Morton. The Life and Ideas of Robert Owen (London, Lawrence & Wishart, 1962)

- F. A. Packard. Life of Robert Owen (Philadelphia: Ashmead & Evans, 1866)

- Frank Podmore Robert Owen: a biography – Vol 1 (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1906).

- Frank Podmore Robert Owen: a biography – Vol 2 (London: Hutchinson & Co., 1906).

- David Santilli. Life Of the Mill Man (London, B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1987)

- William Lucas Sargant. Robert Owen and his social philosophy (London, 1860)

- Richard Tames. Radicals, Railways & Reform (London, B.T. Batsford Ltd, 1986)

- Robert Owen: Welsh Radical & Co-operative Pioneer by Troy Southgate

Other works about him

- Arthur Bestor, Backwoods Utopias (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1950, second edition, 1970).

- Gregory Claeys. Machinery, Money and the Millennium: From Moral Economy to Socialism 1815–1860 (Princeton University Press, 1987)

- Gregory Claeys. Citizens and Saints. Politics and Anti-Politics in Early British Socialism (Cambridge University Press, 1989)

- R. E. Davies. The Life of Robert Owen, philanthropist and social reformer, an appreciation (Robert Sutton, 1907)

- R. A. Davis and F. J. O'Hagan, Robert Owen (London; Continuum Press, 2010)

- E. Dolleans. Robert Owen (Paris, 1905).

- I. Donnachie, Robert Owen. Owen of New Lanark and New Harmony (2000)

- Auguste Fabre. Un socialiste pratique, Robert Owen (Nìmes, Bureaux de l'Émancipation, 1896).

- John F. C. Harrison. Robert Owen and the Owenites in Britain and America: Quest for the New Moral World (New York, 1969).

- Alexander Herzen. My Past and Thoughts (University of California Press, 1982) – one chapter is devoted to Owen.

- G. J. Holyoake, The history of co-operation in England: its literature and its advocates – Vol 1 (London, 1906)

- G. J. Holyoake, The history of co-operation in England: its literature and its advocates – Vol 2 (London, 1906)

- The National Library of Wales. A bibliography of Robert Owen, the socialist (1914)

- H. Simon, Robert Owen: sein Leben und seine Bedeutung für die Gegenwart (Jena, 1905)

External links

- Template:Worldcat id

- Brief biography at the New Lanark World Heritage Site

- The Robert Owen Museum

- Video of Owen's wool mill

- Brief biography at Cotton Times

- Brief biography at the University of Evansville

- "Robert Owen and the Co-operative movement"

- Brief biography at The History Guide

- Brief biography at age-of-the-sage.org

- Heaven On Earth: The Rise and Fall of Socialism at PBS

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- 1771 births

- 1858 deaths

- Cooperative organisers

- Founders of utopian communities

- People from Powys

- Utopian socialists

- Utopists

- Welsh agnostics

- 19th-century Welsh businesspeople

- 18th-century Welsh businesspeople

- Welsh business theorists

- Welsh philanthropists

- Welsh socialists

- British reformers

- Social reformers