Ajanta Caves

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

The Ajanta Caves | |

| Location | Lenapur, Soyagon Taluka, Aurangabad District, Maharashtra State, India |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, vi |

| Reference | 242 |

| Inscription | 1983 (7th Session) |

| Area | 8,242 ha |

| Buffer zone | 78,676 ha |

| Coordinates | 20°33′11″N 75°42′0″E / 20.55306°N 75.70000°E |

The Ajanta Caves in Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state of India are about 29 rock-cut Buddhist cave monuments which date from the 2nd century BCE to about 480 or 650 CE.[1][2] The caves include paintings and rock cut sculptures described as among the finest surviving examples of ancient Indian art, particularly expressive paintings that present emotion through gesture, pose and form.[3][4][5]

According to UNESCO, these are masterpieces of Buddhist religious art that influenced Indian art that followed.[6] The caves were built in two phases, the first group starting around the 2nd century BC, while the second group of caves built around 400–650 CE according to older accounts, or all in a brief period of 460 to 480 according to Walter M. Spink.[7] The site is a protected monument in the care of the Archaeological Survey of India,[8] and since 1983, the Ajanta Caves have been a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Ajanta Caves constitute ancient monasteries and worship halls of different Buddhist traditions carved into a 250 feet wall of rock.[9][10] The caves also present paintings depicting the past lives and rebirths of the Buddha, pictorial tales from Aryasura's Jatakamala, as well as rock-cut sculptures of Buddhist deities in vogue between the 2nd century BCE and 5th century CE.[9][11][12] Textual records suggest that these caves served as a monsoon retreat for monks, as well as a resting site for merchants and pilgrims in ancient India.[9] While vivid colours and mural wall painting were abundant in Indian history as evidenced by historical records, Caves 16, 17, 1 and 2 of Ajanta form the largest corpus of surviving ancient Indian wall-painting.[13]

The Ajanta Caves site are mentioned in the memoirs of several medieval era Chinese Buddhist travelers to India and by a Mughal era official of Akbar era in early 17th century.[14] They were covered by jungle until accidentally "discovered" and brought to the Western attention in 1819 by a colonial British officer on a tiger hunting party.[15] The Ajanta caves are located on the side of a rocky cliff that is on the north side of a U-shaped gorge on the small river Waghur,[16] in the Deccan plateau.[17][18] Further round the gorge are a number of waterfalls, which when the river is high are audible from outside the caves.[19]

With the Ellora Caves, Ajanta is the major tourist attraction of Maharashtra. They are about 59 kilometres (37 miles) from the city of Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India, 60 kilometres (37 miles) from Pachora, 104 kilometres (65 miles) from the city of Aurangabad, and 350 kilometres (220 miles) east-northeast from Mumbai.[9][20] They are 100 kilometres (62 miles) from the Ellora Caves, which contain Hindu, Jain as well as Buddhist caves, the last dating from a period similar to Ajanta. The Ajanta style is also found in the Ellora Caves and other sites such as the Elephanta Caves and the cave temples of Karnataka.[21]

History

The Ajanta Caves are generally agreed to have been made in three distinct periods, the first belonging to the 2nd century BCE to 1st century CE, and second period that followed several centuries later.[22][23][24]

The caves consist of 36 identifiable foundations,[9] some of them discovered after the original numbering of the caves from 1 through 29. The later identified caves have been suffixed with the letters of the alphabet, such as 15A identified between originally numbered caves 15 and 16.[25] The cave numbering is a convention of convenience, and has nothing to do with chronological order of their construction.[26]

Caves of the first (Satavahana) period

The earliest group constructed consists of caves 9, 10, 12, 13 and 15A. This grouping, and that they belong to the Hinayana (Theravada[26]) tradition of Buddhism, is generally accepted by scholars, but there are differing opinions on which century the early caves were built.[27][28] According to Walter Spink, they were made during the period 100 BCE to 100 CE, probably under the patronage of the Hindu Satavahana dynasty (230 BCE – c. 220 CE) who ruled the region.[29][30] Other datings prefer the period of the Maurya Empire (300 BCE to 100 BCE).[31] Of these, caves 9 and 10 are stupa containing worship halls of chaitya-griha form, and caves 12, 13, and 15A are vihāras (see the architecture section below for descriptions of these types).[25]

According to Spink, once the Satavahana period caves were made, the site was not further developed for a considerable period until the mid-5th century.[32] However, the early caves were in use during this dormant period, and Buddhist pilgrims visited the site according to the records left by Chinese pilgrim Fa Hien around 400 CE.[25]

Caves of the later, or Vākāṭaka, period

The second phase of construction at the Ajanta Caves site began in the 5th century. For a long time it was thought that the later caves were made over an extended period from the 4th to the 7th centuries CE,[33] but in recent decades a series of studies by the leading expert on the caves, Walter M. Spink, have argued that most of the work took place over the very brief period from 460 to 480 CE,[32] during the reign of Hindu Emperor Harishena of the Vākāṭaka dynasty.[34][35][36] This view has been criticised by some scholars,[37] but is now broadly accepted by most authors of general books on Indian art, for example Huntington and Harle.

The second phase is attributed to the theistic Mahāyāna,[26] or Greater Vehicle tradition of Buddhism.[38][39] Caves of the second period are 1–8, 11, 14–29, some possibly extensions of earlier caves. Caves 19, 26, and 29 are chaitya-grihas, the rest viharas. The most elaborate caves were produced in this period, which included some refurbishing and repainting of the early caves.[40][26][41]

Spink states that it is possible to establish dating for this period with a very high level of precision; a fuller account of his chronology is given below.[42] Although debate continues, Spink's ideas are increasingly widely accepted, at least in their broad conclusions. The Archaeological Survey of India website still presents the traditional dating: "The second phase of paintings started around 5th – 6th centuries A.D. and continued for the next two centuries".

According to Spink, the construction activity at the incomplete Ajanta Caves was abandoned by wealthy patrons in about 480 CE, a few years after the death of Harishena. However, states Spink, the caves appear to have been in use for a period of time as evidenced by the wear of the pivot holes of caves constructed close to 480 CE.[43] According to Richard Cohen, 7th-century Chinese traveler Xuanzang's reports about the caves, and the scattered graffiti from the medieval centuries uncovered at the site suggests that the Ajanta Caves were known and probably in use, but without a stable or steady Buddhist community presence at the site.[14] The Ajanta caves are mentioned in the 17th-century text Ain-i-Akbari by Abu al-Fazl, as twenty four rock-cut cave temples each with remarkable idols.[14]

Rediscovery by the Western world

On 28 April 1819, a British officer named John K Smith, of the 28th Cavalry, while hunting tiger, "discovered" the entrance to Cave No. 10 when a local shepherd boy guided him to the location and the door. The caves were well known by locals already.[44] Captain Smith went to a nearby village and asked the villagers to come to the site with axes, spears, torches and drums, to cut down the tangled jungle growth that made entering the cave difficult.[44] He then vandalised the wall by scratching his name and the date over the painting of a bodhisattva. Since he stood on a five-foot high pile of rubble collected over the years, the inscription is well above the eye-level gaze of an adult today.[45] A paper on the caves by William Erskine was read to the Bombay Literary Society in 1822.[46]

Within a few decades, the caves became famous for their "exotic" setting, impressive architecture, and above all their exceptional and unique paintings. A number of large projects to copy the paintings were made in the century after rediscovery. In 1848, the Royal Asiatic Society established the "Bombay Cave Temple Commission" to clear, tidy and record the most important rock-cut sites in the Bombay Presidency, with John Wilson as president. In 1861 this became the nucleus of the new Archaeological Survey of India.[47]

During the colonial era, the Ajanta site was in the territory of the princely state of the Hyderabad and not British India.[48] In early 1920s, the Nizam of Hyderabad appointed people to restore the artwork, converted the site into a museum and built a road to bring tourists to the site for a fee. These efforts resulted in early mismanagement, states Richard Cohen, and hastened the deterioration of the site. Post-independence, the state government of Maharashtra built arrival, transport, facilities and better site management. The modern Visitor Center has good parking facilities and public conveniences and ASI operated buses run at regular intervals from Visitor Center to the caves.[48]

The Ajanta Caves, along with the Ellora Caves, have become the most popular tourist destination in Maharashtra, and are often crowded at holiday times, increasing the threat to the caves, especially the paintings.[49][full citation needed] In 2012, the Maharashtra Tourism Development Corporation announced plans to add to the ASI visitor centre at the entrance complete replicas of caves 1, 2, 16 & 17 to reduce crowding in the originals, and enable visitors to receive a better visual idea of the paintings, which are dimly-lit and hard to read in the caves.[50]

Paintings

Mural paintings survive from both the earlier and later groups of caves. Several fragments of murals preserved from the earlier caves (Caves 9 and 11) are effectively unique survivals of ancient painting in India from this period, and "show that by Sātavāhana times, if not earlier, the Indian painters had mastered an easy and fluent naturalistic style, dealing with large groups of people in a manner comparable to the reliefs of the Sāñcī toraņa crossbars".[51]

Four of the later caves have large and relatively well-preserved mural paintings which, states James Harle, "have come to represent Indian mural painting to the non-specialist",[51] and represent "the great glories not only of Gupta but of all Indian art".[53] They fall into two stylistic groups, with the most famous in Caves 16 and 17, and apparently later paintings in Caves 1 and 2. The latter group were thought to be a century or more later than the others, but the revised chronology proposed by Spink would place them in the 5th century as well, perhaps contemporary with it in a more progressive style, or one reflecting a team from a different region.[54] The Ajanta frescos are classical paintings and the work of confident artists, without cliches, rich and full. They are luxurious, sensuous and celebrate physical beauty, aspects that early Western observers felt were shockingly out of place in these caves presumed to be meant for religious worship and ascetic monastic life.[55]

The paintings are in "dry fresco", painted on top of a dry plaster surface rather than into wet plaster.[56] All the paintings appear to be the work of painters supported by discriminating connoisseurship and sophisticated patrons from an urban atmosphere. We know from literary sources that painting was widely practised and appreciated in the Gupta period. Unlike much Indian mural painting, compositions are not laid out in horizontal bands like a frieze, but show large scenes spreading in all directions from a single figure or group at the centre.[55] The ceilings are also painted with sophisticated and elaborate decorative motifs, many derived from sculpture.[54] The paintings in cave 1, which according to Spink was commissioned by Harisena himself, concentrate on those Jataka tales which show previous lives of the Buddha as a king, rather than as deer or elephant or another Jataka animal. The scenes depict the Buddha as about to renounce the royal life.[57]

In general the later caves seem to have been painted on finished areas as excavating work continued elsewhere in the cave, as shown in caves 2 and 16 in particular.[58] According to Spink's account of the chronology of the caves, the abandonment of work in 478 after a brief busy period accounts for the absence of painting in places including cave 4 and the shrine of cave 17, the later being plastered in preparation for paintings that were never done.[57]

Copies

The paintings have deteriorated significantly since they were rediscovered, and a number of 19th-century copies and drawings are important for a complete understanding of the works. A number of attempts to copy the Ajanta paintings began in the 19th-century for European and Japanese museums. Some of these works have later been lost in natural and fire disasters. In 1846 for example, Major Robert Gill, an Army officer from Madras Presidency and a painter, was appointed by the Royal Asiatic Society to make copies of the frescoes on the cave walls.[60] Gill worked on his painting at the site from 1844 to 1863. He made 27 copies of large sections of murals, but all but four were destroyed in a fire at the Crystal Palace in London in 1866, where they were on display.[61] Gill returned to the site, and recommenced his labours, replicating the murals until his death in 1875.[citation needed]

Another attempt was made in 1872 when the Bombay Presidency commissioned John Griffiths to work with his students to make copies of Ajanta paintings, again for shipping to England. They worked on this for thirteen years and some 300 canvases were produced, many of which were displayed at the Imperial Institute on Exhibition Road in London, one of the forerunners of the Victoria and Albert Museum. But in 1885 another fire destroyed over a hundred of the paintings in storage in a wing of the museum. The V&A still has 166 paintings surviving from both sets, though none have been on permanent display since 1955. The largest are some 3 × 6 metres. A conservation project was undertaken on about half of them in 2006, also involving the University of Northumbria.[62] Griffith and his students had unfortunately painted many of the paintings with "cheap varnish" in order to make them easier to see, which has added to the deterioration of the originals, as has, according to Spink and others, recent cleaning by the ASI.[63][full citation needed]

A further set of copies were made between 1909 and 1911 by Christiana Herringham (Lady Herringham) and a group of students from the Calcutta School of Art that included the future Indian Modernist painter Nandalal Bose. The copies were published in full colour as the first publication of London's fledgling India Society. More than the earlier copies, these aimed to fill in holes and damage to recreate the original condition rather than record the state of the paintings as she was seeing them. According to one writer, unlike the paintings created by her predecessors Griffiths and Gill, whose copies were influenced by British Victorian styles of painting, those of the Herringham expedition preferred an 'Indian Renascence' aesthetic of the type pioneered by Abanindranath Tagore.[64]

Early photographic surveys were made by Robert Gill, who learnt to use a camera from about 1856, and whose photos, including some using stereoscopy, were used in books by him and Fergusson (many are available online from the British Library),[65] then Victor Goloubew in 1911 and E.L. Vassey, who took the photos in the four volume study of the caves by Ghulam Yazdani (published 1930–1955).[66]

Another attempt to make copies of the murals was made by the Japanese artist Arai Kampō (荒井寛方:1878–1945) after being invited by Rabindranath Tagore to India to teach Japanese painting techniques.[67] He worked on making copies with tracings on Japanese paper from 1916 to 1918 and his work was conserved at Tokyo Imperial University until the materials perished during the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake.[68]

-

A painting from Cave 1. This cave features, states Spink, superb murals and imperial quality paintings.[69]

-

Cave 2, showing the extensive paint loss of many areas. It was never finished by its artists, and shows Vidhura Jataka.[70]

-

Section of the mural in Cave 17, the 'coming of Sinhala'. The prince (Prince Vijaya) is seen in both groups of elephants and riders.

-

Copy of Ajanta painting, in Musée Guimet, Paris

-

Hamsa jâtaka, cave 17. This painting probably shows one of the previous lives of the Buddha

Significance

The Ajanta Caves painting are a significant source of socio-economic information in ancient India. The Cave 1, for example, shows some Sassanian (or Persian) characters, as do other paintings that states Spink, are "filled with such foreign" looking types.[73] This likely reflects merchants and visitors from the flourishing trade routes of that age.[73][74]

Architecture and sculpture

Site

The caves are carved out of flood basalt rock of a cliff, part of the Deccan Traps formed by successive volcanic eruptions at the end of the Cretaceous geological period. The rock is layered horizontally, and somewhat variable in quality.[75] This variation within the rock layers required the artists to amend their carving methods and plans in places. The inhomogeneity in the rock have also led to cracks and collapses in the centuries that followed, as with the lost portico to cave 1. Excavation began by cutting a narrow tunnel at roof level, which was expanded downwards and outwards; as evidenced by some of the incomplete caves such as the partially-built vihara caves 21 through 24 and the abandoned incomplete cave 28.[76]

The sculpture artists likely worked at both excavating the rocks and making the intricate carvings of pillars, roof and idols; further, the sculpture and painting work inside a cave were an integrated parallel tasks.[77] A grand gateway to the site was carved, at the apex of the gorge's horseshoe between caves 15 and 16, as approached from the river, and it is decorated with elephants on either side and a nāga, or protective Naga (snake) deity.[78] Similar methods and application of artist talent is observed in other cave temples of India, although many with very different themes such as those from Hinduism and Jainism. These include the Ellora caves, Ghototkacha caves, Elephanta Caves, Bagh Caves, Badami Caves and Aurangabad Caves.[79]

The caves from the first period seem to have been paid for by a number of different patrons to gain merit, with several inscriptions recording the donation of particular portions of a single cave. The later caves were each commissioned as a complete unit by a single patron from the local rulers or their court elites, again for merit in Buddhist afterlife beliefs as evidenced by inscriptions such as those in Cave 17.[80] After the death of Harisena, smaller donors motivated by getting merit added small "shrinelets" between the caves or add statues to existing caves, and some two hundred of these "intrusive" additions were made in sculpture, with a further number of intrusive paintings, up to three hundred in cave 10 alone.[81]

Monasteries

The majority of the caves are vihara halls with symmetrical square plans. To each vihara hall are attached smaller square dormitory cells cut into the walls.[82] A vast majority of the caves were carved in the second period, wherein a shrine or sanctuary is appended at the rear of the cave, centred on a large statue of the Buddha, along with exuberantly detailed[clarification needed] reliefs and deities near him as well as on the pillars and walls, all carved out of the natural rock.[83] This change reflects the shift from Hinayana to Mahāyāna Buddhism. These caves are often called monasteries.

The central square space of the interior of the viharas is defined by square columns forming a more or less square open area. Outside this are long rectangular aisles on each side, forming a kind of cloister. Along the side and rear walls are a number[clarification needed] of small cells entered by a narrow doorway; these are roughly square, and have small niches on their back walls. Originally they had wooden doors.[84] The centre of the rear wall has a larger shrine-room behind, containing a large Buddha statue. The viharas of the earlier period are much simpler, and lack shrines.[85] Spink places the change to a design with a shrine to the middle of the second period, with many caves being adapted to add a shrine in mid-excavation, or after the original phase.[86]

The plan of Cave 1 (right) shows one of the largest viharas, but is fairly typical of the later group. Many others, such as Cave 16, lack the vestibule to the shrine, which leads straight off the main hall. Cave 6 is two viharas, one above the other, connected by internal stairs, with sanctuaries on both levels.[87]

Worship halls

The other type of main hall architecture is the narrower rectangular plan with high arched ceiling type chaitya-griha – literally, "the house of stupa". This hall is longitudinally divided into a nave and two narrower side aisles separated by a symmetrical row of pillars, with a stupa in the apse.[88][89] The stupa is surrounded by pillars and a concentric walking space for circumambulation. Some of the caves have elaborate carved entrances, some with large windows over the door to admit light. There is often a colonnaded porch or verandah, with another space inside the doors running the width of the cave. The oldest worship halls at Ajanta were built in the 2nd to 1st century BCE, the newest ones in late 5th century CE, and the architecture of both resembles the architecture of a Christian church, but without the crossing or chapel chevette.[90] The Ajanta Caves follow the Cathedral-style architecture found in still older rock-cut cave carvings of ancient India, such as the Lomas Rishi Cave of the Ajivikas near Gaya in Bihar dated to the 3rd century BCE.[91] These chaitya-griha are called worship or prayer halls.[92][93]

The four completed chaitya halls are caves 9 and 10 from the early period, and caves 19 and 26 from the later period of construction. All follow the typical form found elsewhere, with high ceilings and a central "nave" leading to the stupa, which is near the back, but allows walking behind it, as walking around stupas was (and remains) a common element of Buddhist worship (pradakshina). The later two have high ribbed roofs carved into the rock, which reflect timber forms,[94] and the earlier two are thought to have used actual timber ribs and are now smooth, the original wood presumed to have perished.[95] The two later halls have a rather unusual arrangement (also found in Cave 10 at Ellora) where the stupa is fronted by a large relief sculpture of the Buddha, standing in Cave 19 and seated in Cave 26.[85] Cave 29 is a late and very incomplete chaitya hall.[96]

The form of columns in the work of the first period is very plain and un-embellished, with both chaitya halls using simple octagonal columns, which were later painted with images of the Buddha, people and monks in robes. In the second period columns were far more varied and inventive, often changing profile over their height, and with elaborate carved capitals, often spreading wide. Many columns are carved over all their surface with floral motifs and Mahayana deities, some fluted and others carved with decoration all over, as in cave 1.[97][98]

Cave-by-cave

Cave 1

Cave 1 was built on the eastern end of the horse-shoe shaped scarp and is now the first cave the visitor encounters. This cave, when first made, would have been a less prominent position, right at the end of the row. According to Spink, it is one of the last caves to have been excavated, when the best sites had been taken and was never fully inaugurated for worship by the dedication of the Buddha image in the central shrine. This is shown by the absence of sooty deposits from butter lamps on the base of the shrine image, and the lack of damage to the paintings that would have happened if the garland-hooks around the shrine had been in use for any period of time. Although there is no epigraphic evidence, Spink believes that the Vākāţaka Emperor Harishena was the benefactor of the work, and this is reflected in the emphasis on imagery of royalty in the cave, with those Jataka tales being selected that tell of those previous lives of the Buddha in which he was royal.[99]

The cliff has a more steep slope here than at other caves, so to achieve a tall grand facade it was necessary to cut far back into the slope, giving a large courtyard in front of the facade. There was originally a columned portico in front of the present facade, which can be seen "half-intact in the 1880s" in pictures of the site,[100] but this fell down completely and the remains, despite containing fine carvings, were carelessly thrown down the slope into the river, from where they have been lost.

This cave has one of the most elaborate carved façades, with relief sculptures on entablature and ridges, and most surfaces embellished with decorative carving. There are scenes carved from the life of the Buddha as well as a number of decorative motifs. A two pillared portico, visible in the 19th-century photographs, has since perished. The cave has a front-court with cells fronted by pillared vestibules on either side. These have a high plinth level. The cave has a porch with simple cells on both ends. The absence of pillared vestibules on the ends suggests that the porch was not excavated in the latest phase of Ajanta when pillared vestibules had become a norm. Most areas of the porch were once covered with murals, of which many fragments remain, especially on the ceiling. There are three doorways: a central doorway and two side doorways. Two square windows were carved between the doorways to brighten the interiors.[101]

Each wall of the hall inside is nearly 40 feet (12 m) long and 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Twelve pillars make a square colonnade inside supporting the ceiling, and creating spacious aisles along the walls. There is a shrine carved on the rear wall to house an impressive seated image of the Buddha, his hands being in the dharmachakrapravartana mudra. There are four cells on each of the left, rear, and the right walls, though due to rock fault there are none at the ends of the rear aisle.[102]

The walls and ceilings of Cave 1 are covered with paintings in a fair state of preservation, though the full scheme was never completed. The scenes depicted are mostly didactic, devotional, and ornamental, with scenes from the Jataka stories of the Buddha's former lives as a bodhisattva), the life of the Gautama Buddha, and those of his veneration. The two most famous individual painted images at Ajanta are the two over-life-size figures of the protective bodhisattvas Padmapani and Vajrapani on either side of the entrance to the Buddha shrine on the wall of the rear aisle (see illustrations above).[103][104]

Cave 1 also features a fresco with characters with foreign looking faces and dresses. One of these shows Sassanian (or Persian) characters bowing before an Indian king. According to Spink, James Fergusson, a 19th-century architectural historian, had decided that this scene corresponded to the Persian ambassador in 625 CE to the court of the Hindu Chalukya king Pulakeshin II.[73] An alternate theory has been that the fresco represents a Hindu ambassador visiting the Persian king Khusrau II in 625 CE, a theory that Fergusson disagreed with.[105][106] These assumptions by colonial British era art historians, state Spink and other scholars, has been responsible for wrongly dating this painting to the 7th century, when in fact this reflects an incomplete Harisena-era painting of a Jataka tale with the representation of trade between India and distant lands such as Sassanian near East that was common by the 5th century.[73][107][108]

| Cave No.1 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 2

Cave 2, adjacent to Cave 1, is known for the paintings that have been preserved on its walls, ceilings, and pillars. It looks similar to Cave 1 and is in a better state of preservation. This cave is best known for its feminine focus, intricate rock carvings and paint artwork yet it is incomplete and lacks consistency.[109][110] One of the 5th-century frescoes in this cave also shows children at a school, with those in the front rows paying attention to the teacher, while those in the back row are shown distracted and acting.[111]

Cave 2 was started in the 460s, but mostly carved between 475 and 477 CE, probably sponsored and influenced by a woman closely related to emperor Harisena.[112] It has a porch quite different from Cave 1. Even the façade carvings seem to be different. The cave is supported by robust pillars, ornamented with designs. The front porch consists of cells supported by pillared vestibules on both ends.[113]

The hall has four colonnades which are supporting the ceiling and surrounding a square in the center of the hall. Each arm or colonnade of the square is parallel to the respective walls of the hall, making an aisle in between. The colonnades have rock-beams above and below them. The capitals are carved and painted with various decorative themes that include ornamental, human, animal, vegetative, and semi-divine motifs.[113] Major carvings include that of goddess Hariti. She is a Buddhist deity who originally was the demoness of smallpox and a child eater, who the Buddha converted into a guardian goddess of fertility, easy child birth and one who protects babies.[110][111]

The paintings on the ceilings and walls of this porch have been widely published. They depict the Jataka tales that are stories of the Buddha's life in former existences as Bodhisattva. Just as the stories illustrated in cave 1 emphasise kingship, those in cave 2 show many noble and powerful women in prominent roles, leading to suggestions that the patron was an unknown woman.[114] The porch's rear wall has a doorway in the center, which allows entrance to the hall. On either side of the door is a square-shaped window to brighten the interior.

Paintings appear on almost every surface of the cave except for the floor. At various places, the artwork has become eroded due to decay and human interference. Therefore, many areas of the painted walls, ceilings, and pillars are fragmentary. The painted narratives of the Jataka tales are depicted only on the walls, which demanded the special attention of the devotee. They are didactic in nature, meant to inform the community about the Buddha's teachings and life through successive rebirths. Their placement on the walls required the devotee to walk through the aisles and 'read' the narratives depicted in various episodes. The narrative episodes are depicted one after another although not in a linear order. Their identification has been a core area of research since the site's rediscovery in 1819. Dieter Schlingloff's identifications have updated our knowledge on the subject.[citation needed]

| Cave No.2 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 3

Cave 3 is merely a start of an excavation; according to Spink it was begun right at the end of the final period of work and soon abandoned.[115]

Cave 4

The Archaeological Survey of India board outside the caves gives the following detail about cave 4:"This is the largest monastery planned on a grandiose scale but was never finished. An inscription on the pedestal of the buddha's image mentions that it was a gift from a person named Mathura and paleographically belongs to 6th century A.D. It consists of a verandah, a hypostylar hall, sanctum with an antechamber and a series of unfinished cells. The rear wall of the verandah contains the panel of Litany of Avalokiteśvara". Spink, in contrast, dates this along with all other caves to pre-480 CE period.

The sanctuary houses a colossal image of the Buddha in preaching pose flanked by bodhisattvas and celestial nymphs hovering above.

| Cave No.4 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Caves 5-8

Caves 5 and 6 are viharas, the latter on two floors, that were late works of which only the lower floor of cave 6 was ever finished. The upper floor of cave 6 has many private votive sculptures, and a shrine Buddha, but is otherwise unfinished.[115] Cave 7 has a grand facade with two porticos but, perhaps because of faults in the rock, which posed problems in many caves, was never taken very deep into the cliff, and consists only of the two porticos and a shrine room with antechamber, with no central hall. Some cells were fitted in.[116]

Cave 8 was long thought to date to the first period of construction, but Spink sees it as perhaps the earliest cave from the second period, its shrine an "afterthought". The statue may have been loose rather than carved from the living rock, as it has now vanished. The cave was painted, but only traces remain.[116]

Caves 9

Caves 9 and 10 are the two chaitya halls from the first period of construction, though both were also undergoing an uncompleted reworking at the end of the second period. Cave 10 was perhaps originally of the 1st century BCE and cave 9 about a hundred years later. The small "shrinelets" called caves 9A to 9D and 10A also date from the second period, and were commissioned by individuals.[117]

Cave 9 may for many reasons be considered not only the oldest Chaitya in Ajanta, but as one of the earliest of its class yet discovered in the west of India. It is probably not so old as that at Bhaja, for the whole of its front is in stone, with the single exception of the open screen in the arch, which was in wood, as was the case in all the early caves of Hinayana class. There is, however, no figure sculpture on the front, as at Karle and Kondane, and all the ornaments upon it are copied more literally from the wood than in almost any other cave, except that at Bedsa, which it very much resembles. Another peculiarity indicative of age is that its plan is square, and the aisles are flat roofed and lighted by windows, and the columns that divide them from the nave slope inwards at an angle somewhere between that found at Bhaja and that at Bedsa.[118]

In many respects the design of its facade resembles that of the Chaitya at Nasik caves, but it is certainly earlier, and on the whole there can be little hesitation in classing it with the caves at Bedsa, and consequently in assuming its date to be about the 1st century BCE.[118]

This Chaitya is 45 feet deep by 22 feet 9 inches wide and 23 feet 2 inches high. A colonnade all round divides the nave from the aisles, and at the back the pillars form a semicircular apse, in the centre of which stands the dagoba, about 7 feet in diameter; its base is a plain cylinder, 5 feet high, supporting a dome 4 feet high by about 6 feet 4 inches in diameter, surmounted by a square capital about 2 feet high, and carved on the sides in imitation of the "Buddhist railing." It represents a relic box, and is crowned by a projecting lid, a sort of abacus consisting of six plain fillets, each projecting over the one below. This most probably supported a wooden umbrella, as at Karle. Besides the two pillars inside the entrance, the nave has 21 plain octagonal columns without base or capital, 10 feet 4 inches high, supporting an entablature, 6 feet 8 inches deep, from which the vaulted roof springs, and which has originally been fitted with wooden ribs. The aisles are flat-roofed, and only an inch higher than the columns; they are lighted by a window opening into each. Over the front doorway is the great window, one of the peculiar features of a Chaitya-cave: it is of horse-shoe form, about 11 feet high, with an inner arch, about 9 feet high, just over the front pillars of the nave. Outside this is the larger arch with horizontal ribs, of which five on each side project in the direction of the centre, and eleven above in a vertical direction. The barge-board or facing of the great arch here is wider than usual, and perfectly plain. It probably was plastered, and its ornamentation, which was in wood at Bhaja, was probably here reproduced in painting. On the sill of this arch is a terrace, 2 feet wide, with a low parapet in front, wrought in the "Buddhist-rail" pattern; outside this, again, is another terrace over the porch, about 3 feet wide, and extending the whole width of the cave, the front of it being ornamented with patterns of the window itself as it must have originally appeared, with a wooden frame of lattice-work in the arch. At each end of this, on the wall at right angles to the facade, is sculptured a colossal figure of the Buddha, and on the projecting rock on each side there is a good deal of sculpture, but all of a much later date than the temple itself, and possibly of the 5th century. The porch of the door has partly fallen away. It had a cornice above supported by two very wooden-like struts, similar to those in the Bhaja Chaitya-cave.[118]

The paintings in this cave consist principally of figures of the Buddha along the left wall, where there are at least six, each with a triple umbrella, and some traces of buildings. On the back wall is a fragment, extending nearly its whole length, containing figures of the Buddha variously engaged, disciples, worshippers, a dagoba, etc... This is probably of older date than the generality of the paintings found in the other caves, but it may fairly be questioned whether it is of so early an age as the fragments on the walls in Cave X. It is of high artistic merit, however, which makes one the more regret that no more of it is left.[118]

On the front wall over the left window a layer of painting has dropped off, laying bare one of the earliest fragments left, possibly a version of the Jataka of Sibi or Siwi Raja, who gave his eyes to Indra, who appeared to him in the form of a mendicant to test him.[118]

| Cave No.9 (1st century CE) | |

| |

Cave 10

Caves 10 and 9 are the two chaitya halls from the first period of construction, though both were also undergoing an uncompleted reworking at the end of the second period. Cave 10 was perhaps originally of the 1st century BCE and cave 9 about a hundred years later. The small "shrinelets" called caves 9A to 9D and 10A also date from the second period, and were commissioned by individuals.[119]

Cave 10 is the second and largest Chaitya of the group, and must have been when complete a very fine cave. There is some little difficulty in speaking of the date with confidence, as the facade has entirely fallen away, and the pillars inside are plain octagons, without either bases or capitals, and having been at one time plastered and painted there are no architectural details by which its age can be ascertained. There is, however, one constructional feature which is strongly indicative of a comparatively modern date. The roof of the nave was adorned with wooden ribs, like all the caves described above, though all these are now gone; but the aisles here are adorned with stone ribs carved in imitation of wood. The later group of caves at Ajanta, the 5th century CE Mahayana caves, all have stone ribs, both in the nave and aisles, and this seems a step in that direction, but so far as is known the first.[120]

Another circumstance indicative of a more modem date is the position of this cave in the series. It is higher up in the rock, and very much larger than Cave No.9, and it seems most improbable that having a large and roomy Chaitya they should afterwards excavate a smaller one close along side of it on a lower level, and in a more inconvenient form. The contrary is so much more likely to be the case, as the community extended, and more accommodation was wanted, that it may fairly be assumed, from this circumstance alone, that Cave No.10 is the more modern of the two Chaityas, though at what interval it is difficult to say in consequence of the absence of architectural details in the larger cave.[120]

It measures 41 feet 1 inch wide, about 95 feet deep, and 36 feet high. The inner end of the cave, as well as of the colonnade that surrounds the nave, is semi-circular, the number of columns in the latter being thirty-nine plain octagons, two more than in the great Chaitya at Karla Caves, but many of them are broken. They are 14 feet high, and over them rises a plain entablature 9 feet deep, from which springs the arched roof, rising 12 feet more, with a span of about 23 feet. Like the oldest Chaitya caves at Bhaja, Karle, Bedsa, Kondane, etc..., it has been ribbed with wood. The aisles are about 6 feet wide, with half-arched roofs, ribbed in the rock. The chaitya or dagoba is perfectly plain, with a base or lower drum, 15 feet in diameter; the dome is rather more than half a sphere, and supports the usual capital, consisting of an imitation box, covered by a series of thin square slabs, each projecting a little over the one below it.

Inscription of Vasithiputra

There is an inscription on the front of the great arch at the right hand side, which reads:[120]

Vasiputasa katahd dito gharmukha danam.

" The gift of a house-door (front) by Vasithiputra."— Inscription of Cave No.10[120]

If it could be certain that this was the Vasishthiputra Pulumavi of the Nasik inscriptions, it would be possible to at once refer this cave to the 2nd century CE, and the paleography would support such a date. But then does it mean that Vasishthiputra began the excavation and carved out the facade ? or does it only imply that he inserted, in a Chaitya cave already existing, a new front ? Now, in excavating the floor under the great arch, it was found that a wall had been built across the front of immense bricks of admirable texture and colour, several tiers of which still remain in situ. This may have been Vasishthiputra's work, and the cave itself may be of an earlier date.[120]

Earliest paintings

The whole of this cave has been painted. Both these Chaitya Caves (Cave 9 and Cave 10) still retain a great deal of the fresco paintings with which they were at one time completely adorned. They are of various ages, and none of them probably coeval with the cave.[120]

The paintings in cave 10 include some surviving from the early period, many from an incomplete programme of modernisation in the second period, and a very large number of smaller late intrusive images for votive purposes, around the 479–480 CE, nearly all Buddhas and many with donor inscriptions from individuals. These mostly avoided over-painting the "official" programme and after the best positions were used up are tucked away in less prominent positions not yet painted; the total of these (including those now lost) was probably over 300, and the hands of many different artists are visible.[121]

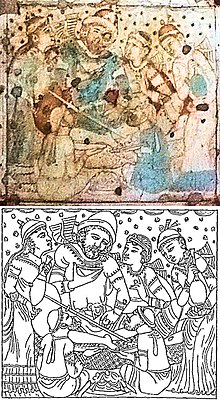

The paintings in Cave 10 may possibly be of the age of Vasishthiputra, who certainly was one of the Satakarnis and contemporary with the Andhrabhritya, and possibly with the excavation of the cave. Their general character may be judged from the attached drawing. Both figures and costume are very different from anything found in any of the other caves, but they resemble as far as sculpture can be compared with painting the costumes found among sculptures at Sanchi in the 1st century of our era.[120]

| Cave No.10 (1st century BCE, most paintings 5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 16

Cave 16 along with Cave 17 and Cave 26 with sleeping Buddha, were some of the many caves sponsored by the Hindu Vakataka prime minister Varahadeva.[122]

| Cave No.16 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 17

Cave 17 along with Cave 16 with two great stone elephants at the entrance and Cave 26 with sleeping Buddha, were some of the many caves sponsored by the Hindu Vakataka prime minister Varahadeva.[122] Cave 17 had additional donors such as the local king Upendragupta, as evidenced by the inscription therein.[123] It features a large and most sophisticated vihara design, along with some of the best-preserved and well known paintings of all the caves. The Vihara includes a colonnaded porch, a number of pillars each with a distinct style, a peristyle design for the interior hall, a shrine antechamber located deep in the cave, larger windows and doors for more light, along with extensive integrated carvings of Indian gods and goddesses.[124] The grand scale of the carving also introduced errors of taking out too much rock to shape the walls, states Spink, which led to the cave being splayed out toward the rear.[125]

The paintings in Cave 17 include those of the Buddha in various styles, Avalokitesvara, frescoes with the story of Udayin and Gupta, the story of Nalagiri, the Visvantara Jataka, the Hamsa Jataka, the Wheel of life, a panel celebrating various ancient Indian musicians, a panel that tells of Prince Simhala’s expedition to Sri Lanka.[126][127] This includes details of a shipwreck and the escape from ogresses by a flying horse. Other notable paintings include a princess applying makeup, lovers in scenes of dalliance, and a wine drinking scene of a couple with the woman and man amorously seated, while attendants watch them.[72]

| Cave No.17 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 18

Cave 18 is merely a porch, 19 feet 4 inches by 8 feet 10 inches, with two pillars, apparently intended as a passage into the next cave.[128]

Cave 19

Cave 19 is the third of the Chaitya caves, and differs only in its details from Nos.9 and 10. It is 24 feet wide by 46 feet long and 24 feet 4 inches high. But whereas the former two were perfectly plain, this is elaborately carved throughout. Besides the two in front, the nave has 15 columns 11 feet high. These pillars are square at the base, which is 2 feet 7 inches high with small figures on the corners; then they have an octagonal belt about a foot broad, above which the shaft is circular, and has two belts of elaborate tracery, the intervals being in some cases plain and in others fluted with perpendicular or spiral flutes; above the shaft is a deep torus of slight projection between two fillets, wrought with a leaf pattern, and over this again is a square tile, supporting a bracket capital, richly sculptured with a Buddha in the centre and elephants or sardulas with two riders or flying figures, on the brackets. The architrave consists of two plain narrow fascias. The whole entablature is 5 feet deep, and the frieze occupying exactly the same position as a triforium would in a Christian church, is divided into compartments by rich bands of arabesque, and in the compartments are figures of Buddha alternately sitting cross-legged and standing. The dome rises 8 feet 4 inches, whilst the width of the nave is only 12 feet 2 inches, so that the arch is higher than a semicircle, and is ribbed in stone. Between the feet of every fourth and fifth rib is carved a tiger's head.[129]

The Chaitya or dagoba is a composite one; it has a low pedestal, on the front of which stand two demi-columns, supporting an arch containing a low-relief figure of the Buddha. On the under part of the capital above the dome there is also a small sculpture of Buddha, and over the chudamani, or four fillets of the capital, are three umbrellas in stone, one above another, each upheld on four sides by small figures. These may be symbolic of Buddha "the bearer of the triple canopy, the canopy of the heavenly host, the canopy of mortals, and the canopy of eternal emancipation," or they are typical of the bhuvanas or heavens of the celestial Bodhisattvas and Buddhas.[129]

The roof of the aisles is flat and has been painted, chiefly with ornamental flower scrolls, Buddhas, and Chaityas, and on the walls there have been paintings of theBuddha generally with attendants, the upper two rows sitting, and in the third mostly standing, but all with aureoles behind the heads.[129]

There is but one entrance to this cave. The whole is in excellent preservation, as is also the facade and the lower part, the accumulated materials that had fallen from above have now been removed, and display entire what must be considered one of the most perfect specimens of Buddhist art in India. Over the whole facade of this Chaitya temple projects a bold and carefully carved cornice, broken only at the left end by a heavy mass of rock having given way. In front has been an enclosed court, 33 feet wide by 30 feet deep, but the left side of it has nearly disappeared. The porch and whole front of the cave is covered by elaborate and beautiful carving.[129]

There is no inscription on this cave by which its date could be ascertained, but from its position and its style of architecture there can be little doubt that it is of about the same age as the two Viharas 16. and 17, which are next to it, and consequently it may safely be assumed that it was excavated near the middle of the sixth century, a few years before or after 550 CE.[129]

Beside the beauty and richness of the details, it is interesting as the first example with of a Chaitya cave wholly in stone. Not only are the ribs of the nave and the umbrella over the Dagoba, but all the ornaments of the fagade are in stone. Nothing in or about it is or ever was in wood, and many parts are so lithic in design that if we did not know to the contrary, we might not be able to detect at once the originals from which they were derived. The transformation from wood to stone is complete in this cave, and in the next one.[129]

Outside to the left, and at right angles to the facade of the cave, is a sculpture representing a Naga raja and his wife. He with a seven-headed cobra hood. She with one serpent's head behind her. At Sanchi in the first century when the Naga kings first appear the serpent has only five heads, but the females there are still with only one. At Amravati the heads of the serpent were multiplied to 21, and in modem times to 100 or 1000. Who these Naga people were has not jet been settled satisfactorily. They occur frequently on the doorways and among the paintings at Ajanta, and generally wherever Buddhism can be found. They were also adopted by the Jainas and Vaishnaves, but their origin is certainly Buddhist.[129]

On the other side opposite this image of the Naga Raja is a porch, with two pilasters in front, which probably was a chawari or place of rest for pilgrims. It has a room at each end, about 10 feet by 8 feet 4 inches. The capitals of the pillars in front of it are richly wrought with mango branches and clusters of grapes in the middle of each.[129]

On each side the great arch is a large male figure in rich headdress, that on the left holds a bag, and is Kubera, the god of wealth, a favourite of Buddhism. The corresponding figure on the right is nearly the same, and many figures of Buddha sitting or standing occupy compartments in the facade, and at the sides of it.[129]

| Cave No.19 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 20

Cave 20 is a small Yihara with two pillars and two pilasters in front of its verandah. One pillar is broken, but on each side of the capitals there is a pretty bracket statuette of a female under a canopy of foliage. The roof of the verandah is hewn in imitation of beams and rafters. There is a cell at each end of the verandah and two on each side of the hall, which is 28 feet 2 inches wide by 25 feet 4 inches deep and 12.5 feet high, and has no columns. The roof is supported only by the walls and the front of the antechamber, which advances 7 feet into the cave, and has in front two columns in antis, surmounted by a carved entablature filled with seven figures of the Buddha and attendants. The statue in the shrine has probably been painted red, and is attended by two large figures of Indras,with great tiaras, bearing chauris and some round object in the left band, while on the front of the seat, which has no lions at the corners, are carved two deer as vahana, with a chakra or wheel between them. The painting in this cave has now almost entirely disappeared.[131]

The probability is that this cave should not be considered so much as a Vihara or a Dharmasala as the vestry hall or chapter house of the group. If this is so these four caves, 16 to 20, form the most complete Buddhist establishment to be found among the Western caves. Two Viharas, one Chaitya, and one place of assembly. Hitherto it has generally been supposed that the halls of the Viharas formed the place of meeting for the monks, and so that probably it did, each for their convent, but it seems probable that besides this there was a general hall of meeting attached to each group, and that this was one of them.[131]

Cave 24

Cave 24 was intended for a 20 pillared vihara, 73 feet wide by 75 feet deep, and if completed it would probably have been one of the most beautiful in the whole series, but the work was stopped before completion. The verandah was long choked up with earth, and of the six pillars in it only one is now standing ; the rest appear to have fallen down. The bracket capitals still hang from the entablature, and the carved groups on them are in the best style of workmanship. In two of the capitals and in those of the chapels at the end of the verandah the corners are left above the torus, and wrought into pendant scroll leaf ornaments. The work on the doors and windows is elaborate. Inside only one column has been finished.[132]

Here we learn how these caves were excavated by working long alleys with the pickaxe into the rock and then breaking down the intervening walls, except where required for supporting columns. There is some sculpture in an inner apartment of the chapel outside the verandah to the left, but much in the usual style.[132]

Cave 25

This is a small vihara with a verandah of two pillars; the hall is 26 feet 5 inches wide by 25 feet 4 inches deep without cell or sanctuary. It has three doors; and at the left end of the verandah is a chamber with cells at the right and back. In front is an enclosed space, about 30 feet by 14, with two openings in front, and a door to the left leading on to the terrace of the next cave.[132]

Cave 26

This is the fourth Chaitya-cave, and bears a strong resemblance to Cave 19. It is larger however, and is very much more elaborately ornamented with sculpture, but that generally is somewhat inferior in design, and monotonous in the style of its execution, showing a distinct tendency towards that deterioration which marked the Buddhist art of the period. It is also certainly more modern than No.19, though the two are not separated by any long interval. Still the works in Cave 26 seem to have been continued to the very latest period at which Buddhist art was practiced at Ajanta, and it was contemporary with the unfinished caves which immediately preceded it in the series. It may possibly have been commenced in the end of the 6th century, but its sculptures extend down to the middle of the 7th, or to whatever period may be ascertained as that at which the Buddhists were driven from these localities. This was certainly after Hiwen Thsang's visit to the neighbourhood in 640, and it may not have been for 10 or 20 years after this time.[133]

Once it had a broad verandah along the whole front, supported by four columns, of which portions of three still remain, and at each end of the verandah there was a chamber with two pillars and pilasters very like those in the left side chapel of Cave 3 at Aurangabad. The court outside the verandah has extended some way right and left, and on the right side are two panels above one another, containing the litany of Avalokiteswara, similar to that in Cave 4, and to the right of it is a standing figure of the Buddha in the asiva mudra, holding up the right hand in the attitude of blessing. One of these panels, however, is much hidden by the accumulation of earth in front of them, and the other is entirely concealed by it. Over the verandah, in front of the great window and upper facade of the cave, there was a balcony, about 8 feet wide and 40 feet long, entered at the end from the front of the last cave. The sill of the great arch was raised 3 feet above this, and at the inner side of the sill, which is 7 feet 2 inches deep, there is a stone parapet or screen, 3 feet high, carved in front with small Buddhas. The outer arch is 14 feet high, but the inner one from the top of the screen is only 8 feet 10 inches. The whole facade, outside the great arch and the projecting side-walls at the ends of the balcony, has been divided into compartments of various sizes sculptured with Buddhas. On each side the great arch is a seated figure of Kubera, the god of wealth, and beyond it, in a projecting alcove, is a standing Buddha. On the upper parts of the end walls of this terrace there is, on each side, a figure of Buddha standing with his sela or robe descending from the left shoulder to the ankle, leaving the right shoulder bare: these figures are about 16 feet high.[133]

Under the figure on the left is an inscription in a line and a half, being a dedication by the Sakya Bhikshu Bhadanta Grunakara. On the left of the entrance is a longer inscription recording the construction of the cave by Devaraja and his father Bhavviraja, ministers of Asmakaraja. This is important as connecting the excavators of this cave with Cave 17 and the large Vihara at Grhatotkacha.[133]

Besides the central door, there is a smaller side one into each aisle. The temple is 67 feet 10 inches deep, 36 feet 3 inches wide, and 31 feet 3 inches high. The nave besides the two in front, has twenty-six columns, is 17 feet 7 inches wide, and 33 feet 8 inches long to the front of the dagoba; the pillars behind it are plain octagons, with bracket capitals, and the others somewhat resemble those in the verandah of Cave 2; they are 12 feet high, and a four-armed bracket dwarf is placed over each capital on the front of the narrow architrave. The frieze projects a few inches over the architrave, and is divided into compartments elaborately sculptured. The stone ribs of the roof project inwards, and the vault rises 12 feet to the ridge pole.[133]

Dagoba

The body of the chaitya or dagoba is cylindrical, but with a broad face in front, carved with pilasters, cornice, and mandapa top; in the centre is a Buddha sitting on a sinhasana or throne with lions upholding the seat, his seld reaching to his ankles, his feet on a lotus upheld by two small figures with Naga canopies, behind which, and under the lions, are two elephants. The rest of the cylinder is divided by pilasters into compartments containing figures of Buddha standing in various attitudes. The dome has a compressed appearance, its greatest diameter being at about a third of its height, and the representation of the box above is figured on the sides with a row of standing and another of sitting Buddhas; over it are some eight projecting fillets or tenias, crowned by a fragment of a small stone umbrella. The aisles of this Chaitya-cave contain a good deal of sculpture, much of it defaced. In the right aisle there are large compartments with Buddhas sculptured in high-relief with attendants; their feet rest on the lotus upheld by Naga-protected figures with rich headdresses, and others sitting beside them. Over the Buddhas are flying figures, and above them a line of arabesques with small compartments containing groups.[133]

The Buddha's Parinirvana

On the left wall, near the small door is a gigantic figure of Buddha about 23 feet 3 inches in length, reclining on a couch. This represents the death of the great ascetic, the Parinirvana. There is a tree at the head and another at the foot of the figure, and Ananda, the relative and attendant of Buddha, standing under the second. This figure has also its face turned to the north. Above the large figure are several very odd ones, perhaps representing the divas "making the air ring," as the legend says, "with celestial music, and scattering flowers and incense." Among them is perhaps Indra, the prince of the thirty-two devas of Trayastrinshas, on his elephant. In front of the couch are several other figures, his disciples or bhikshus, exhibiting their grief at his departure, and a worshiper with a flower in his hand and some little offerings in a tray.[133]

Temptation of the Buddha

Farther along the wall, beyond a figure of Buddha teaching between two attendants, a Bodhisattva on the left and perhaps Padmapani on the right, there is a large and beautiful piece of sculpture that has perplexed every one who has attempted to explain it. To the left a prince, Mara, stands with what appears to be a bow and arrow in his hands and protected by an umbrella, and before him some sitting, others dancing are a number of females, his daughters Tanha, Rati, and Ranga, with richly adorned headdresses. A female beats the three drums, two of which stand on end which she beats with one hand, and the other lies on its side while she almost sits on it and beats it with the other hand. Mara appears again at the right side, disappointed at his failure. Several of the faces are beautifully cut. Above are his demon forces attacking the great ascetic sitting under the Bodhi tree, with his right hand pointing to the earth and the left in his lap (the bhumisparsa mudra), while the drum of the devas is being beat above him. This is the same subject that is represented in painting in Cave No.1. The painting contains more detail, and a greater number of persons are represented in it, than in this sculpture, but the story and the main incidents are the same in both. On the whole this sculpture is perhaps, of the two, the best representation of a scene which was so great a favorite with the artists of that age. Besides this it is nearly entire, while a great deal of the plaster on which the other was painted has pealed off, leaving large gaps, which it is now almost impossible to fill up.[133]

| Cave No.26 (5th century CE) | |

| |

Cave 27

Cave 27 is the last accessible vihara. The front is broken away and a huge fragment of rock lies before the cave, which is about 43 feet wide and 31 deep, without pillars. It has never been finished, and the antechamber to the shrine is only blocked out. There are three cells in the left side, two in the back, and one in the portion of the left side that remains.[134]

Cave 28

Cave 28 is the beginning of a Chaitya cave high up on the scarp between Nos.21 and 22; but little more than the top of the great arch of the window has been completed.[134]

Cave 29

Cave 29 is the verandah of a vihara beyond Cave 27, supported by six rough-hewn pillars and two pilasters. No.28 is very difficult of access, and 29 is inaccessible.[134]

Spink's chronology and cave history

Walter M. Spink has over recent decades developed a very precise and circumstantial chronology for the second period of work on the site, which unlike earlier scholars, he places entirely in the 5th century. This is based on evidence such as the inscriptions and artistic style, dating of nearby cave temple sites, comparative chronology of the dynasties, combined with the many uncompleted elements of the caves.[135] He believes the earlier group of caves, which like other scholars he dates only approximately, to the period "between 100 BCE – 100 CE", were at some later point completely abandoned and remained so "for over three centuries". This changed during the Hindu emperor Harishena of the Vakataka Dynasty,[34] who reigned from 460 to his death in 477, who sponsored numerous new caves during his reign. Harisena's rule extended the Central Indian Vakataka Empire to include a stretch of the east coast of India; the Gupta Empire ruled northern India at the same period, and the Pallava dynasty much of the south.[32]

According to Spink, Harisena encouraged a group of associates, including his prime minister Varahadeva and Upendragupta, the sub-king in whose territory Ajanta was, to dig out new caves, which were individually commissioned, some containing inscriptions recording the donation. This activity began in many caves simultaneously about 462. This activity was mostly suspended in 468 because of threats from the neighbouring Asmaka kings. Thereafter work continued on only Caves 1, Harisena's own commission, and 17–20, commissioned by Upendragupta. In 472 the situation was such that work was suspended completely, in a period that Spink calls "the Hiatus", which lasted until about 475, by which time the Asmakas had replaced Upendragupta as the local rulers.[136]

Work was then resumed, but again disrupted by Harisena's death in 477, soon after which major excavation ceased, except at cave 26, which the Asmakas were sponsoring themselves. The Asmakas launched a revolt against Harisena's son, which brought about the end of the Vakataka Dynasty. In the years 478–480 CE major excavation by important patrons was replaced by a rash of "intrusions" – statues added to existing caves, and small shrines dotted about where there was space between them. These were commissioned by less powerful individuals, some monks, who had not previously been able to make additions to the large excavations of the rulers and courtiers. They were added to the facades, the return sides of the entrances, and to walls inside the caves.[137] According to Spink, "After 480, not a single image was ever made again at the site".[138]

Spink does not use "circa" in his dates, but says that "one should allow a margin of error of one year or perhaps even two in all cases".[139]

Role of Hindus in building Buddhist caves

The Ajanta Caves were built in a period when both the Buddha and the Hindu gods were simultaneously revered in Indian culture. According to Spink and other scholars, not only the Ajanta Caves but other nearby cave temples were sponsored and built by Hindus.[34][140] This is evidenced by inscriptions wherein the role as well as the Hindu heritage of the donor is proudly proclaimed. According to Spink,

That one could worship both the Buddha and the Hindu gods may well account for Varahadeva's participation here, just as it can explain why the emperor Harisena himself could sponsor the remarkable Cave 1, even though most scholars agree that he was certainly a Hindu, like earlier Vakataka kings.

— Walter Spink, Ajanta: History and Development, Cave by Cave,[140]

Impact on modern paintings

The Ajanta paintings, or more likely the general style they come from, influenced painting in Tibet[141] and Sri Lanka.[142]

The rediscovery of ancient Indian paintings at Ajanta provided Indian artists examples from ancient India to follow. Nandalal Bose experimented with techniques to follow the ancient style which allowed him to develop his unique style.[143] Abanindranath Tagore and Syed Thajudeen also used the Ajanta paintings for inspiration.

See also

Notes

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 173.

- ^ The largest buddha statue in Ajanta is found in cave 19 of size 5m. The precise number varies according to whether or not some barely started excavations, such as cave 15A, are counted. The ASI say "In all, total 30 excavations were hewn out of rock which also include an unfinished one", UNESCO and Spink "about 30". The controversies over the end date of excavation is covered below.

- ^ Trudy Ring; Noelle Watson; Paul Schellinger (2012). Asia and Oceania. Routledge. pp. 17, 14–19. ISBN 978-1-136-63979-1.

- ^ Hugh Honour; John Fleming (2005). A World History of Art. Laurence King. pp. 228–230. ISBN 978-1-85669-451-3.

- ^ Michell 2009, p. 336.

- ^ Ajanta Caves, India: Brief Description, UNESCO World Heritage Site. Retrieved 27 October 2006.

- ^ Ajanta Caves: Advisory Body Evaluation, UNESCO International Council on Monuments and Sites. 1982. Retrieved 27 October 2006., p.2.

- ^ "Ajanta Caves". Retrieved 19 May 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Richard Cohen (2013). William M. Johnston (ed.). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Routledge. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-1-136-78716-4.

- ^ Aravinda Prabhakar Jamkhedkar (2009). Ajanta. Oxford University Press. pp. 61–62, 71–73. ISBN 978-0-19-569785-8.

- ^ Richard S. Cohen (1998), Nāga, Yakṣiṇī, Buddha: Local Deities and Local Buddhism at Ajanta, History of Religions, University of Chicago Press, Vol. 37, No. 4 (May, 1998), pages 360–400

- ^ Benoy K. Behl; Sangitika Nigam (1998). The Ajanta caves: artistic wonder of ancient Buddhist India. Harry N. Abrams. pp. 164, 226. ISBN 978-0-8109-1983-9.

- ^ Harle 1994, pp. 355–361, 460.

- ^ a b c Richard Cohen (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 32, 82. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2.

- ^ Walter M. Spink (2005). Ajanta: History and Development, Volume 5: Cave by Cave. BRILL Academic. pp. 3, 139. ISBN 90-04-15644-5.

- ^ variously spelled Waghora or Wagura

- ^ Map of Ajanta Caves, UNESCO

- ^ Narayan Sanyal (1984). Immortal Ajanta. Bharati. p. 7.

- ^ Spink (2006), 2

- ^ Indian Railways (1996). Bhusawal Division: Tourism (Ajanta and Ellora). pp. 40–43.

- ^ Harle 1994, pp. 118–122.

- ^ Aravinda Prabhakar Jamkhedkar (2009). Ajanta. Oxford University Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-19-569785-8.

- ^ Spink 2009, pp. 1–2. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ Louise Nicholson (2014). National Geographic India. National Geographic Society. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-1-4262-1183-6.

- ^ a b c Walter M. Spink (2005). Ajanta: History and Development, Volume 5: Cave by Cave. BRILL Academic. pp. 4, 9. ISBN 90-04-15644-5.

- ^ a b c d Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1994). Asia and Oceania. Routledge. pp. 14–19. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- ^ Michell 2009, pp. 335–336.

- ^ Walter M. Spink (2005). Ajanta: History and Development, Volume 5: Cave by Cave. BRILL Academic. pp. 4, 9, 163–170. ISBN 90-04-15644-5.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Benoy K. Behl; Sangitika Nigam (1998). The Ajanta caves: artistic wonder of ancient Buddhist India. Harry N. Abrams. pp. 20, 26. ISBN 978-0-8109-1983-9., Quote: "The caves of the earlier phase at Ajanta date from around the second century BC, during the rule of the Satavahana dynasty. Although the Satavahanas were Hindu rulers, they (...)"

- ^ Nagaraju 1981, pp. 98–103

- ^ a b c Spink 2009, p. 2 harvnb error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ The UNESCO World Heritage List website for example says "The 29 caves were excavated beginning around 200 BC, but they were abandoned in AD 650 in favour of Ellora"

- ^ a b c Richard Cohen (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2., Quote: Hans Bakker's political history of the Vakataka dynasty observed that Ajanta caves belong to the Buddhist, not the Hindu tradition. That this should be so is already remarkable in itself. By all we know of Harisena he was a Hindu; (...).

- ^ Geri Hockfield Malandra (1993). Unfolding A Mandala: The Buddhist Cave Temples at Ellora. State University of New York Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-7914-1355-5.

- ^ Fred S. Kleiner (2016). Gardner's Art through the Ages: A Concise Global History. Cengage. p. 468. ISBN 978-1-305-57780-0.

- ^ For example, Karl Khandalavala, A. P. Jamkhedkar, and Brahmanand Deshpande. Spink, vol. 2, pp. 117–134

- ^ Sara L. Schastok (1985). The Śāmalājī Sculptures and 6th Century Art in Western India. BRILL Academic. p. 40. ISBN 90-04-06941-0.

- ^ Walter M. Spink (2005). Ajanta: Arguments about Ajanta. Brill Academic. p. 127. ISBN 978-90-04-15072-0.

- ^ Spink 2009, pp. 2–3. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ Richard Cohen (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2.

- ^ Spink (2006), 4–6 for the briefest summary of his chronology, developed at great length in his Ajanta: History and Development 2005.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 5–6, 160–161.

- ^ a b Richard Cohen (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 77–78. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2.

- ^ Spink (2006), 139 and 3 (quoted): "Going down into the ravine where the caves were cut, he scratched his inscription (John Smith, 28th Cavalry, 28th April, 1819) across the innocent chest of a painted Buddha image on the thirteenth pillar on the right in Cave 10..."

- ^ Upadhya, 3

- ^ Gordon, 231–234

- ^ a b Richard Cohen (2006). Beyond Enlightenment: Buddhism, Religion, Modernity. Routledge. pp. 51–58. ISBN 978-1-134-19205-2.

- ^ Cohen's chapter 2 discusses the history and future of visitors to Ajanta.

- ^ "Tourist centre to house replicas of Ajanta caves", Times of India, 5 August 2012, accessed 24 October 2012; see Cohen 51 for an earlier version of the proposal, recreating caves 16, 17 and 21.

- ^ a b Harle 1994, p. 355.

- ^ The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion, Pia Brancaccio, BRILL, 2010 p.82

- ^ Harle 1994, p. 356.

- ^ a b Harle 1994, pp. 355–361.

- ^ a b Harle 1994, p. 359.

- ^ Harle 1994, p. 361.

- ^ a b Spink 2008

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Detail from this painting in the V&A

- ^ Upadhyay, Om Dutt (1994). The Art of Ajanta and Sopoćani. Motilal Banarsidas Publisher. pp. 2–3. ISBN 81-208-0990-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Gordon, 234–238; Conserving the copies of the Ajanta cave paintings at the V&A

- ^ Conserving the copies of the Ajanta cave paintings at the V&A, Victoria & Albert Museum, Conservation Journal, Spring 2006 Issue 52, accessed 24 October 2012

- ^ Cohen, 50–51

- ^ Rupert Richard Arrowsmith, "An Indian Renascence and the rise of global modernism: William Rothenstein in India, 1910–11", The Burlington Magazine, vol.152 no.1285 (April 2010), pp.228–235.

- ^ Gordon, 236; example from the British Library (search on "Gill, Robert Ajanta")

- ^ Upadya, 2–3

- ^ M. L. Ahuja,Eminent Indians: Ten Great Artists, Rupa Publications, 2012 p.51.

- ^ Caterina Bon Valsassina; Marcella Ioele (2014). Ajanta Dipinta - Painted Ajanta Vol. 1 e 2. Gangemi Editore Spa. pp. 150–152. ISBN 978-88-492-7658-9.

- ^ Spink 2009, pp. 71–72, 132–139. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ Spink 2009, p. 148, Figure 46. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ Spink 2006, p. 19.

- ^ a b Spink 2009, pp. 201–202. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ a b c d Spink 2009, p. 132. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ Schlingloff, Dieter (1976). "Kalyanakarin's Adventures. The Identification of an Ajanta Painting". Artibus Asiae. 38 (1): 5–28. doi:10.2307/3250094. JSTOR 3250094.

- ^ "horizontally bedded alternate flows of massive and amygdular lava" is a technical description quoted by Cohen, 37

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Spink 2006, p. 28.

- ^ Spink, 10; Michell 340

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 21–24, 38, 74–76, 115, 151–153, 280.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 5, 15, 32–33, 80, 249.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 5, 15, 32–33, 80, 126–130, 249–259.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 73–85, 100–104, 182.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 18, 37, 45–46.

- ^ Spink (2006), 148

- ^ a b Harle, 118–122; Michell 335–343

- ^ Spink (2006), 142

- ^ Michell, 338

- ^ Jain, Rajesh K.; Garg, Rajeev (2004). "Rock-Cut Congregational Spaces in Ancient India". Architectural Science Review. 47 (2): 199–203. doi:10.1080/00038628.2004.9697044.

- ^ Suresh Vasant (2000), Tulja Leni and Kondivte Caitya-gṛhas: A Structural Analysis, Ars Orientalis, Vol. 30, Supplement 1. Chāchājī: Professor Walter M. Spink Felicitation Volume (2000), pages 23–32

- ^ David Efurd (2013). Vimalin Rujivacharakul, H. Hazel Hahn; et al. (eds.). Architecturalized Asia: Mapping a Continent through History. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 140–145. ISBN 978-988-8208-05-0.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|editor=(help) - ^ Born, Wolfgang (1943). "The Origin and the Distribution of the Bulbous Dome". The Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians. 3 (4): 32–48. doi:10.2307/901122.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 12, 94, 161–162, 228.

- ^ Keith Bellows (2008). Sacred Places of a Lifetime: 500 of the World's Most Peaceful and Powerful Destinations. National Geographic Society. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-4262-0336-7.

- ^ UNESCO, Brief description

- ^ Michell, 339

- ^ Spink (2006), 12–13

- ^ Spink (2006), 18, and in the accounts of individual caves; Michell, 336

- ^ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1909), THE BUDDHIST AND HINDU ARCHITECTURE OF INDIA, Journal of the Royal Society of Arts, Vol. 57, No. 2937 (MARCH 5, 1909), pages 316–329

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 17, 31.

- ^ Spink (2006), 17; 1869 photo by Robert Gill at the British Library, showing the porch already rather less than "half-intact"

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 17–21.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 29–31.

- ^ Harle 1994, pp. 359–361.

- ^ Spink 2006, p. 29.

- ^ Jas. Fergusson (1879), On the Identification of the Portrait of Chosroes II among the Paintings in the Caves at Ajanta, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 11, No. 2 (Apr., 1879), pages 155–170

- ^ Spink 2006, p. 27.

- ^ Anand Krishna (1981), An exceptional group of painted Buddha figures at Ajanta, The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, Volume 4, Number 1, pages 96–100 with footnote 1

- ^ a b Spink 2009, pp. 74–75. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ a b Claudine Bautze-Picron (2002), Nidhis and Other Images of Richness and Fertility in Ajaṇṭā, East and West, Vol. 52, No. 1/4 (December 2002), pages 245–251

- ^ a b Spink 2009, pp. 150–152. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFSpink2009 (help)

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 7–8, 40–43.

- ^ a b Spink 2006, pp. 40–54.

- ^ Spink 2006, pp. 13–14

- ^ a b Spink 2006, p. 8

- ^ a b Spink 2006, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Spink (2006), 9; 140–141

- ^ a b c d e Fergusson, James; Burgess, James (1880). The cave temples of India. London : Allen. pp. 289–291.

- ^ Spink (2006), 9; 140–141