Wikipedia:Reference desk/Science

of the Wikipedia reference desk.

Main page: Help searching Wikipedia

How can I get my question answered?

- Select the section of the desk that best fits the general topic of your question (see the navigation column to the right).

- Post your question to only one section, providing a short header that gives the topic of your question.

- Type '~~~~' (that is, four tilde characters) at the end – this signs and dates your contribution so we know who wrote what and when.

- Don't post personal contact information – it will be removed. Any answers will be provided here.

- Please be as specific as possible, and include all relevant context – the usefulness of answers may depend on the context.

- Note:

- We don't answer (and may remove) questions that require medical diagnosis or legal advice.

- We don't answer requests for opinions, predictions or debate.

- We don't do your homework for you, though we'll help you past the stuck point.

- We don't conduct original research or provide a free source of ideas, but we'll help you find information you need.

How do I answer a question?

Main page: Wikipedia:Reference desk/Guidelines

- The best answers address the question directly, and back up facts with wikilinks and links to sources. Do not edit others' comments and do not give any medical or legal advice.

October 23

Do old farts dream of flying insects?

I want to know, outside of Germany, are the flying insects disappearing? Do old people remember there being more flying insects in their youth than there are today? 110.22.20.252 (talk) 03:54, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Yes. Bugs are declining. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/2017/08/26/windscreen-phenomenon-car-no-longer-covered-dead-insects/ 196.213.35.146 (talk) 07:31, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- I assume you excluded Germany because you've already seen this: http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0185809 196.213.35.146 (talk) 08:28, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Given the huge increase in vehicular traffic and the general increase in speed it should come as no surprise that there will be a decrease in flying insects. I'm in my 7th decade and I remember in the English countryside when you would look up if a car was approaching, and you could sit at the roadside, the A30, than a major trunk road, and write down vehicle registration numbers (for later sorting and scrutiny) with sometimes 10 or 15 minutes between vehicles. Ah, those days. Richard Avery (talk) 14:29, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- In case it's not clear: the decline is not due to vehicle use per se, that's just how some people notice the fact. The decline in flying insects is associated with pesticide use, habitat loss, habitat degradation, habitat fragmentation, and climate change. SemanticMantis (talk) 14:53, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Given the huge increase in vehicular traffic and the general increase in speed it should come as no surprise that there will be a decrease in flying insects. I'm in my 7th decade and I remember in the English countryside when you would look up if a car was approaching, and you could sit at the roadside, the A30, than a major trunk road, and write down vehicle registration numbers (for later sorting and scrutiny) with sometimes 10 or 15 minutes between vehicles. Ah, those days. Richard Avery (talk) 14:29, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- OP and interested parties should look through the first few paragraphs of that paper, and the first ~30 or so references, many of which document the decline of flying insects in other parts of the world. It's not just Germany, it's fairly widespread around the world. SemanticMantis (talk) 14:53, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Notwithstanding the risibility potential of malodorousness heralded by audible signal due to sudden decompression of postprandial gaseous abdominal distension, this involuntary occurrence is neither a respectful nor a unique designator of persons of advanced maturity, for whom such usage as that in the heading should be deprecated. Blooteuth (talk) 15:52, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- So, if the spiders can't eat as many insects as they were used to will they turn on us? :) . Count Iblis (talk) 22:32, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- I've personally killed some 500 box elder bugs in my house this fall (one 30 seconds ago), so I have to think human population has an effect. StuRat (talk) 23:40, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

"Fun science" for kids using a laser pointer

What "fun science" can I demonstrate to kids, about 10 to 14 years old, using a red (650nm) laser pointer and common household objects and substances? Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 10:22, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- I always thought prisms were cool. Refraction demonstrations maybe? 196.213.35.146 (talk) 10:44, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Diffraction has a demonstration using a red laser. 196.213.35.146 (talk) 10:49, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Before you switch the laser on, ask them what they expect the beam itself to look like. Then show them it's invisible when passing through air. Cue discussion about Star Wars physics? Then make the beam visible by producing smoke in its path, or splashing some flour or whatever.

- Try diffracting the beam through an empty drinking glass by pointing it to the glass off-centre, and mark where the beam lands on a sheet of vertical paper. Test what happens when you fill the glass with water.

- Have the students predict what colour the spot will appear when the laser is shone on white, black, red, and green objects.

- Adrian J. Hunter(talk•contribs) 10:58, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- I have a handy gadget, which started out as expensive school kit but can now be made at home with a few bucks on eBay. A small plastic box to hold the batteries and a switch, with a red laser module mounted in the side of it. But rather than the usual laser pointer, this has a line lens on it, to give a vertical plane of light, relative to the box base.

- The advantage is that you can place this on a sheet of paper and demonstrate mirrors, prisms, lenses etc. and because the light is a plane rather than a line, it's visible as a path right across the paper. It makes ray tracing far simpler.

- A purple laser also shows interesting fluorescence effects, on materials like hardwood, uranium glass and the usual fabrics washed in optical brighteners. Andy Dingley (talk) 11:39, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- This has some suggestions. --Jayron32 11:56, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- One quick thing they might find interesting is to learn that their skin is somewhat transparent. Turn the lights out at night, and have them hold up their hand, then shine the laser pointer through the webbing between the thumb and the rest. The red light travels well through thin skin, so they should see a nice red glow on the other side. I would insist on handling the laser pointer myself, though, so they can't shine it in each other's eyes, potentially causing damage. If this has to be done during the day, use a darkened room or even put hand under a box. (You might be able to see some red light shine through in full light, but it won't be nearly as impressive.)

- You could use this as a talking point to lead into how we are even more transparent to other types of radiation. Also, if your kids have a mixture of skin colors, they might notice that dark-skinned people are less transparent to light. This can lead to a discussion of melanin and how it evolved to protect from UV light, and how this also limits vitamin D production from sunlight, so isn't as prevalent in places with little sunlight. See Vitamin_D#Synthesis_in_the_skin. StuRat (talk) 17:47, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- My apologies if it's already been mentioned, but I always thought the laser pouring water experiment was cool, it simulates the total inner reflection which explains how fiber optics work. Anywho the video is here, enjoy! Drewmutt (^ᴥ^) talk 00:11, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- P.S. Depending on how intense you're lil' guys are there's some easy Double-slit experiments you can do at home to demonstrate quantum mechanics. It's easy to do and the instructions are here. Drewmutt (^ᴥ^) talk

- Please teach laser safety first. -Arch dude (talk) 02:23, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- No, don't try to teach laser safety. It's far too complicated. Instead, limit all exposure to devices with a strongly divergent beam that are inherently eye-safe. Don't have anything around that you can't safely catch an eyeful of, because it _is_ going to happen. Andy Dingley (talk) 15:33, 24 October 2017 (UTC) (using class 4s since thirty-odd years ago)

- This is why I suggested that only the adult should actually handle the laser. Teaching laser safety is fine, but I wouldn't trust kids with lasers any more than I would trust them with guns (and I don't live in a red state, so we don't have any UZI-packing 9-year-old girls: [1]). StuRat (talk) 16:14, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- my daugther (aged 14 then) made a Michelson interferometer using a laser, some fixed mirrors, a half-silvered beam splitter, and one mirror that moved using a piezo element. the cool part was that she could demonstrate that the diffraction pattern varied as the piezo moved, showing that she could measure movements down to a few percent of one wavelength of red light (about 10 nm). Her piezo element was the driver from the inside of a buzzer. iI cost about a dollar. she drove ti with a 9-volt battery and a potentiometer. the only expensive part was the half-silvered mirror. -Arch dude (talk) 02:23, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Thanks everyone for the great ideas. I'll certainly keep safety the first priority. The laser I'm using is a "Class III" 5 mW at 650nm. Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 18:59, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

Reason for large difference in pyrethrin solubility due to a methyl group

In the chemistry section of the pyrethrin page Cinerin II and Jasmolin II are related compounds which differ by the addition of a single methyl group yet Jasmolin II has >7,000x the solubility in water. What accounts for this difference? The methyl group is not polar, if anything I would expect a longer carbon chain to reduce solubility in water not increase it. 208.90.213.186 (talk) 21:30, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- I'm afraid this rickety structure is unreliable. The article cites PubChem for each compound. One of them doesn't have solubility listed. The other credits solubility to a software tool that has since been messed with at the EPA site. I think it actually still exists [2] but applying it might be a goose chase - you're welcome to download it and see what you get. I should note despite a complaint last week, PubChem still says "the atomic weight of chlorine is 70.9..." at [3]. The great thing about replacing human writers with machines is that the machines can do no wrong. Wnt (talk) 22:46, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- OK so it's just made up then. What's wrong with the molar mass of chlorine listed as 70.9? The PubChem page seems clear that it is the diatomic gas. 208.90.213.186 (talk) 22:01, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

Gull intelligence

Is there any research on the cognitive abilities of seagulls? About how well do they compare to corvids and other famously smart birds? My impression is that they're fairly smart, if not corvid level. For example, they can apparently learn to recognize and open food packaging. 2607:F720:F00:4846:1470:AFDA:7A5F:98B5 (talk) 22:00, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Unfortunately, our resident seagull expert, @Kurt Shaped Box:, seems to have retired. You might leave him a note on his talk page, though, in case he returns. StuRat (talk) 22:17, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- One way to compare animal intelligence is the mirror test. StuRat (talk) 23:43, 23 October 2017 (UTC)

- Anecdata: I've often seen gulls trying to attack their reflections, so they evidently don't pass the mirror test. 169.228.159.252 (talk) 03:09, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Not necessarily. They might figure it out, given time. Heck, a person seeing their reflection in a mirror in an unfamiliar, darkened room might be startled, until they figure it out. StuRat (talk) 03:16, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Maybe they're expressing angst. InedibleHulk (talk) 03:19, October 24, 2017 (UTC)

- Seagulls do routinely drop shelled items to feed, there are many videos at youtube. But other than be aggressive and trying to eat anything? I can find no evidence of tool use, co-operative behavior, or cleverness at picked locks. Of course that's absence of evidence. μηδείς (talk) 02:20, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Incidentally, they may not actually recognize food packaging. There could be several other explanations for why they open them:

- 1) The see food through clear packaging.

- 2) They smell food through the packaging.

- 3) They just open similar packaging, on the hope that it contains food. The test here would be if they open non-food packaging of the same size and shape. If so, that means they just try them all. StuRat (talk) 02:55, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- That's a fixed action pattern which is the opposite of intelligence. It serves the gull well often enough that it's an evolutionarily stable behavior. The same can be said of Sand Wasp reproduction. Again, I am not saying there's evidence gulls are stupid. But "they just try them all" is no evidence of their intelligence. μηδείς (talk) 05:48, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Yes, and we need to avoid anthropomorphization. An example I like to use is that if a human community has one well dry up, they may move closer to the remaining working well, using their intelligence. A plant will also "move" closer to it's one remaining water source, in that roots and stems nearby will enlarge while roots and stems further away will whither, but this doesn't mean any intelligence was involved. StuRat (talk) 16:24, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- There's also no stupidity involved when a sunflower "stares" at its photons. Deep down, I think most of us know this, but many still insist these dolts put on the glasses. Even if intended as a public relations boost, not UV protection, the whole altruistic idea is based on a misconception. They don't give a f**ge about us, whether farmed like docile cattle or growing free and wild in a ditch somewhere. We would be in a sorry state without their essential oil. We can't shake their hands, pat their backs or kiss their feet, but can at least not (physically) disturb them while they're busy doing the job we couldn't do as well and would rather not at all. InedibleHulk (talk) 03:47, October 25, 2017 (UTC)

- I'd still like to try my idea of placing small solar panels on sunflowers, to let them do the Sun tracking for us. Who needs expensive machinery for that ? StuRat (talk) 03:53, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Hardly anyone! InedibleHulk (talk) 04:16, October 25, 2017 (UTC)

- I'd still like to try my idea of placing small solar panels on sunflowers, to let them do the Sun tracking for us. Who needs expensive machinery for that ? StuRat (talk) 03:53, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Bird intelligence applies to gulls, loosely. InedibleHulk (talk) 03:56, October 25, 2017 (UTC)

October 24

Source of elements

In File:Nucleosynthesis periodic table.svg this graphic, elements 43, 84-88, and some others are a color that doesn't match anything in the legend. Where do these come from? Bubba73 You talkin' to me? 05:29, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- The brown/tan-ish color is "100% synthetic", according to the popup notes when hovering over those elements as the image description recommends. I agree the legend is deficient, and SVG-implemented image annotations are not as standard as the ImageAnnotator gadget. DMacks (talk) 05:35, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Thanks, the SVG works but I had converted it to a PGN. Synthetic radioisotope helps. Bubba73 You talkin' to me? 13:59, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

Closed Room and extinguishing fire with halon

During a fire, can you still breathe when a halon fire extinguisher is activated? Or is it expected to aerate the room (train/plane) immediately after halon is used?--Hofhof (talk) 23:24, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- Neither. All people are expected to evacuate the room immediately. Only when firemen declare it safe should the air be exchanged and the room reoccupied. StuRat (talk) 23:35, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- And what if the fire is inside a plane or train? --Hofhof (talk) 23:48, 24 October 2017 (UTC)

- You would stop the train immediately and evacuate, or evacuate to other cars. A major fire on a plane in flight is rather deadly, as there aren't many good options for dealing with it. Prevention is the usual course of action. For a small plane fire, usually just a smokey smell, they also land as soon as possible and evacuate. StuRat (talk) 02:12, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Aircraft are one of the few exemptions where you will still find halon. Andy Dingley (talk) 02:54, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Depends on the halon. They're all asphyxiants, but halons (unlike CO2 flood systems) are primarily a chemical agent. So they're used in smaller concentrations than CO2. Halon 1301 was the favoured agent for flood systems, halon 1211 for hand-held extinguishers. Both are considered somewhat toxic and exposure should be restricted, and 1301 was favoured for flooding as it was somewhat safer. They are though safe enough that people can escape a space that has been flooded.

- Halon is no longer used for fire extinguishers, except in some very narrow exceptions, owing to concerns over ozone depletion with CFCs (bromine compounds like the halons too). Halons are still used in some rare situations (I think WP was recently saying that they were completely banned, and there was edit-warring over this) - the Channel Tunnel is one. Flood systems have largely been replaced with CO2. Halotron I is a non-ozone-depleting replacement for halon 1211 in hand-held uses and has similar toxicity - exposure should be limited, but it's better than being in a fire.

- Older agents, notably carbon tetrachloride or Pyrene fluid were remarkably effective extinguishers, but quite evil for toxicity in confined spaces. They're chronically liver toxic for exposure to the fluid and acutely extremely toxic if the fluid is sprayed onto a fire, as phosgene is produced. This was particularly hazardous in sealed spaces, such as tanks - Pyrene extinguishers were fitted to them for a long time, then later only fitted externally. Even smoking near a spill of the fluid has been known to be immediately fatal. Andy Dingley (talk) 00:11, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

October 25

Is it possible to see Philadelphia from New York City?

The highest point in Philly city limits is 1,548 feet above sea level (1255 above ground plus site altitude, both rounded up to at least next foot). New World Trade Center is 1,806 feet above sea level. They're 79.42 miles apart. These are high enough to be seen up to 113 miles apart with the help of average atmospheric refraction but there's 80 miles of trees and hills in the way. Also the tops are only a few feet wide and it would take ridiculously steady air to see antennae that thin with a telescope so the seeing might be theoretical. And one side of the Princeton area is in the way and near the midpoint so there will be buildings. Air below the standard temperature (15°C?) refracts more though and occasionally freak looming occurs with some kind of weird temperature inversion light duct (I think the world record is between Greenland and Iceland). As an alternative tower if this route is blocked, Philadelphia's tallest building is near or at final height now (1,121 feet) and about the same depth into Philadelphia but the Trenton area's in the way. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 08:52, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- It might be easier to spot buildings that are lit up, at night. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 10:18, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- They would if there were an ocean between them. There isn't an ocean between them. There's a place called New Jersey which is not sea-level flat on the line of sight between New York and Philadelphia. There are several lines of low hills that could block such views. If you look at a relief map of New Jersey, you'll also see several lines of hills, for example one near Princeton known as Princeton Ridge or Rocky Hill, it lies in a park known as Woodfield Reserve. Looking here the ridge is at least 260 feet above sea level for the entire line of it, and the peak of the ridge is about 320 feet above sea level. Coupled with the curvature of the earth, this MAY be high enough to cover the view of the tops of the highest buildings of each city from the other. Not entirely positive, but if something did block the view, it would be hills like that. --Jayron32 12:16, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Just to add some evidence possible the other way This thread shows pictures of Philadelphia from Allentown, PA and from Apple Pie Hill, NJ. The Allentown one is from a Helicopter some undetermined height above ground, so it may be cheating, but the NJ one is from a ground level observation from the top of a hill in the Pine Barrens. It's only 30 miles away, though. The 80ish miles to NYC is a different story entirely. --Jayron32 12:22, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- www.skyscraper city.com/showthread.php?t=848608 (remove space, blacklist issues) notes that one cannot see any of Milwaukee from Chicago's Sears Tower, and the line-of-sight between Chicago and Milwaukee is better, there's no significant changes in elevation between the cities; its all fairly flat Lake Michigan coastline, and the distance between the cities is about the same as NYC-Philly. --Jayron32 12:27, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- There are webcams now at WTC1 in NYC and at Comcast Tower, Philadelphia. Equipping them with long lenses and pointing them at each other could answer the OP's question. Since a 193-km path microwave link is achievable a 129 km (80 mile) Philly-NY link should also be feasible if there is indeed a free LOS. Blooteuth (talk) 12:53, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- This utility is VERY useful. It does a line-of-sight topographic cross section between any two points on the earth's surface. Plugging in the heights of the buildings in meters (i used the listed observation for Freedom Tower and the top of the Comcast Technology Center) shows that the topography shouldn't be a problem. There's an easily open line-of-sight assuming that curvature-of-the-Earth issues also aren't a problem. --Jayron32 15:51, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- There are webcams now at WTC1 in NYC and at Comcast Tower, Philadelphia. Equipping them with long lenses and pointing them at each other could answer the OP's question. Since a 193-km path microwave link is achievable a 129 km (80 mile) Philly-NY link should also be feasible if there is indeed a free LOS. Blooteuth (talk) 12:53, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- www.skyscraper city.com/showthread.php?t=848608 (remove space, blacklist issues) notes that one cannot see any of Milwaukee from Chicago's Sears Tower, and the line-of-sight between Chicago and Milwaukee is better, there's no significant changes in elevation between the cities; its all fairly flat Lake Michigan coastline, and the distance between the cities is about the same as NYC-Philly. --Jayron32 12:27, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Just to add some evidence possible the other way This thread shows pictures of Philadelphia from Allentown, PA and from Apple Pie Hill, NJ. The Allentown one is from a Helicopter some undetermined height above ground, so it may be cheating, but the NJ one is from a ground level observation from the top of a hill in the Pine Barrens. It's only 30 miles away, though. The 80ish miles to NYC is a different story entirely. --Jayron32 12:22, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Here [4] is the elevation transect as depicted by the tool Jayron linked. Pretty much everything over 40m elevation should be mutually visible between the the Comcast center and 1WTC, assuming good enough optics, given a flat Earth. However, here [5] is a tool that shows you how much the Earth's curvature gets in the way, and if I'm reading it right, it says that if you're in NYC and your eye is 382 m up (the height of obs. deck at 1WTC), then the horizon will occlude everything in Philly (130 km away) under 284m. Since the Comcast center is 297m tall, you may be just barely able to see it with a good scope on a clear day. SemanticMantis (talk) 17:21, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

Question about gravity assists and space probes

How come space probes that are only intending to fly by the planets of the outer Solar System (i.e. the Pioneer and Voyager probes, as well as Ulysses and New Horizons), such probes tend to go there directly from Earth, but probes intended to orbit around those planets (i.e. Galileo, Cassini, Juno) tend to first make one or more flybys of either Earth, Venus, or both? Narutolovehinata5 tccsdnew 13:30, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

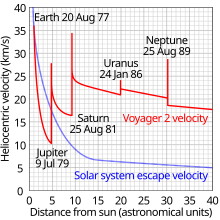

- Voyager and Pioneer made extensive use of gravity assist in their trips. For one example, see the graph at right. Every one of those spikes is a gravity assist event in the travels of Voyager 2. Your question is based on a false premise, so is unanswerable. We cannot answer "why didn't they" when the answer is CLEARLY that "they did". --Jayron32 13:42, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Jayron32: You misunderstood my question: my question is why the other probes made gravity assists of Earth and/or Venus before going to Jupiter, as opposed to the Voyager and Pioneer probes that went from Earth directly to Jupiter without flying by Earth or Venus first. Narutolovehinata5 tccsdnew 13:46, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

In that case the answer is apophenia, which means that your mind is creating false patterns where none exists. Every individual mission is unique, and the decision to choose, or not choose, to use a particular trajectory, and thus a specific set of "gravity assist" events is based not on any pattern based whether or not the probe is going to stop at Jupiter or not, but rather because the specific orientation of the planets at the specific time when the probe was launched and the specific location of the target trajectory either does or does not owe itself to a specific set of gravity assist events. There is no grand scheme on when or when not to use Venus other than "It happens to be in the right place at the right time for our purposes". --Jayron32 15:32, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Jayron32: You misunderstood my question: my question is why the other probes made gravity assists of Earth and/or Venus before going to Jupiter, as opposed to the Voyager and Pioneer probes that went from Earth directly to Jupiter without flying by Earth or Venus first. Narutolovehinata5 tccsdnew 13:46, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- (ec):Its all about conserving fuel and getting free speed boosts from tagging planets. Sometimes they even go in the opposite direction from their target. New Horizons got a boost from Jupiter, Ulysses went by Jupiter to study the Sun. Rmhermen (talk) 13:50, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Here [6] is NASA's HORIZONS system, which can tell you where many thousands of objects are in the solar system, and where they will be in the future, so far as we can tell at present. Here [7] [8] are a few research papers that describe methods for how to plan out gravity assists and flight plans. As you can see, it's pretty heavy stuff, and I'm not sure if there is any "easy" way to understand how they do it. There may be heuristics available (e.g. "It's often good to hit planets in orbital order", or "big backtracks are seldom useful*), but I think the only people qualified to discuss those would be people who have personally worked on planning these things.

- * N.B. These are completely made up by me, and I am not saying they are good or accurate, merely that such rules of thumb may exist. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:53, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

Just as a point of order, if only because it sometimes confuses people (not that it necessarily confused you), it may be perfectly logical to use an assist from Venus to get to Jupiter because, for large parts of the year, Venus would be on the way to Jupiter. If we assume a stationary solar system (just to simplify an otherwise messy problem), any time we have Earth on the opposite side of the sun from Jupiter, Venus would almost always be between them. If Jupiter and Earth were on the same side of the sun, Venus is never useful, and Mars is only useful on the rare instances where it is actually between Earth and Jupiter. People think "Venus is closer to the sun than Earth, and Jupiter is farther, so why use Venus to get to Jupiter" forgetting that these are orbits, and one can easily draw a picture (actually MANY such pictures) where Venus is on the way to Jupiter. --Jayron32 17:43, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- For a specific example in relatively easy to understand terms, here [9] several features of the Juno trajectory are discussed, including info on why those choices were made. SemanticMantis (talk) 16:57, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Gravity assist#Purpose explains this well. Going to an orbit around Venus or Mercury, a spaceship is accelerated too much by the sun to be able to enter orbit, so a

flybygravity assist is used to decelerate. Going to orbit around Jupiter or beyond, the sun slows it down too much, so again it needs a gravity assist, this time to speed up to enter orbit. Flybys don’t need to change their speed, although Voyager 2 used gravity assists to speed up so it wouldn’t take so long to get to Uranus. Loraof (talk) 17:45, 25 October 2017 (UTC)- Loraof gave the best answer here. I've stricken my earlier non-answers because I clearly am confusing the problem with my extemporaneous answers. He's right, I'm wrong here. Forget what I said. That completely answers the OP's question. Mea culpa. --Jayron32 18:05, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- The reason why some probes went directly to Jupiter while others did not is that orbiters were much more massive than first flyby probes. It was just impossible to send them directly to Jupiter - no launch vehicle heavy enough was available at those times. And even if such vehicle had been available, it would have been much more expansive to use it than going by gravity assists. Ruslik_Zero 20:30, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

Hellenistic astrology

This section speaks of the "rising of decans". However, if I got it right, decans as such are basically just distances. So, it cannot really be the decans that "rise", but only the constellations forming them, am I right? Sorry, if this might seem a silly question for any of you.--Cleph (talk) 15:20, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Decans are not distances, Decans are units of time equal to 10 days. As noted at Decans, "Because a new decan also appears heliacally every ten days (that is, every ten days, a new decanic star group reappears in the eastern sky at dawn right before the Sun rises, after a period of being obscured by the Sun's light), the ancient Greeks called them dekanoi (δεκανοί; pl. of δεκανός dekanos) or "tenths" (and when the concept of decans reached northern India, they were called drekkana in Sanskrit.)" I hope that helps explain the name! --Jayron32 15:28, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Jayron32: Thanks a lot. But still, when you say "Decans are units of time", why should one speak of their "rising" or – in case of the article reffered to by you – "appearance"? Aren't it constellations that rise / appear? After all, something that "rises" or "appears" must be physically observable (visible), and units of time do not meet that requirement, do they? So, that wording simply doesn't seem reasonable to me, and probably also wouldn't to the most other laymen reading these articles. But please excuse me if I'm getting something wrong here. Best wishes--Cleph (talk) 17:05, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- No, the word decan comes from a unit of time. The usage of that word means, in the context of astrology, 1/3rd of a constellation. In formalized astrology, a decan just means "1/3rd of a sign". Since each sign lasts about a month, a decan lasts 10 days. To say a "decan is rising" just means "this portion of the constellation is rising". It means the exact same thing in the context of astrology as a certain constellation or planet is "rising". See Ascendant for a discussion of what "rising" means in this context (if that is the source of the confusion). However, to use the term "rising of a decan" is no different than "rising of a constellation". --Jayron32 17:24, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- Ah, okay. I guess it's become clearer to me now. So thanks a lot for that explanation!--Cleph (talk) 18:08, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- No, the word decan comes from a unit of time. The usage of that word means, in the context of astrology, 1/3rd of a constellation. In formalized astrology, a decan just means "1/3rd of a sign". Since each sign lasts about a month, a decan lasts 10 days. To say a "decan is rising" just means "this portion of the constellation is rising". It means the exact same thing in the context of astrology as a certain constellation or planet is "rising". See Ascendant for a discussion of what "rising" means in this context (if that is the source of the confusion). However, to use the term "rising of a decan" is no different than "rising of a constellation". --Jayron32 17:24, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Jayron32: Thanks a lot. But still, when you say "Decans are units of time", why should one speak of their "rising" or – in case of the article reffered to by you – "appearance"? Aren't it constellations that rise / appear? After all, something that "rises" or "appears" must be physically observable (visible), and units of time do not meet that requirement, do they? So, that wording simply doesn't seem reasonable to me, and probably also wouldn't to the most other laymen reading these articles. But please excuse me if I'm getting something wrong here. Best wishes--Cleph (talk) 17:05, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Cleph: Note that there is a much better article at decans that is not decan (astrology). Our article gives the impression that some decans had more of an individual recognizability. The bottom line is that if you have a good view of sunrise and know the stars well enough, you can spot which day it is by which stars are visible just before the sun comes up - and each day they will move up by one degree relative to where they were. (One degree in the sense of one-thirtieth of a month = zodiac constellation or one-tenth of a decan) Wnt (talk) 13:26, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Wnt: Thank you very much, too! Dealing with the article linked by you would probably confuse me even more though. At this point, I must admit that I am really an absolute amateur in this field! However, I tried to get to the bottom of the astrological (!) concept explained at decan (astrology). But what I really don't get is the following statement in the introductory section: "These divisions are known as the "decans" or "decantes" and cover modifications of individual traits What does that exactly refer to?, attributed to minor planetary influences, which temper or blend Same question with the ruling influence of the period And once more…." Can one of you translate that for a six-year-old? PS: I'd say at least that sentence should be rewritten by someone who knows what's what if we still want non-professionals to understand our articles. Don't you think?--Cleph (talk) 18:24, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Well, this is more editorial than answer now... "Astrology" in the ancient sense was in considerable part the respectable science of measuring the true date, with the reasonable extensions of providing useful prognostications of whether it would be a good or a bad idea to plant wheat or start the spring march to war. But the things you mention sound more like the bad sort of "astrology" we think of today, and frankly, I would not be optimistic that they mean anything at all. At the very least, this being the Science desk, I don't have to worry about figuring it out here. ;) Wnt (talk) 23:59, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- You can get some idea of what they're talking about here: [10]. 92.8.218.38 (talk) 14:29, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Both of these fields should've been called astronology till about the 1600s. Kepler invented the quintile, when things are near 0.2 circumferences apart in ecliptic longitude. When the part of astronology that would've been astronomers if they were born later stopped believing astrology the community kept giving readings for awhile to pay for their livings and telescopes. By now of course professional readers are generally really woo people of the kind who would've been one of the last to believe in vampires and the ghost-blocking properties of iron and drowning a pretty virgin to appease the hurricane god threatening villagers' lives. Especially since the computer revolution of 1995 meant that professional astrologers don't even need to know how to use any of the math and tools needed to make a chart anymore. Like a book of house and planet positions or even a book of zillions of birthplace coordinates and historical time zones. Software can give birth charts and progressions and things without adjusting the house positions for latitude and longitude and calculating the missing ones from the ones given and drawing the thing with a compass and protractor and a few other maths. The computer shows a chart with just a time and town name so the astrologer can focus on what's really important: unconscious or conscious warm, cold and hot reading and cherry picking! And predicting! And making these unnecessarily vague and seem less vague than they are! Which isn't hard cause people who believe astrology are some of the right-brainedest people on Earth. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 18:38, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Well, this is more editorial than answer now... "Astrology" in the ancient sense was in considerable part the respectable science of measuring the true date, with the reasonable extensions of providing useful prognostications of whether it would be a good or a bad idea to plant wheat or start the spring march to war. But the things you mention sound more like the bad sort of "astrology" we think of today, and frankly, I would not be optimistic that they mean anything at all. At the very least, this being the Science desk, I don't have to worry about figuring it out here. ;) Wnt (talk) 23:59, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- @Wnt: Thank you very much, too! Dealing with the article linked by you would probably confuse me even more though. At this point, I must admit that I am really an absolute amateur in this field! However, I tried to get to the bottom of the astrological (!) concept explained at decan (astrology). But what I really don't get is the following statement in the introductory section: "These divisions are known as the "decans" or "decantes" and cover modifications of individual traits What does that exactly refer to?, attributed to minor planetary influences, which temper or blend Same question with the ruling influence of the period And once more…." Can one of you translate that for a six-year-old? PS: I'd say at least that sentence should be rewritten by someone who knows what's what if we still want non-professionals to understand our articles. Don't you think?--Cleph (talk) 18:24, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

Vertebrate intelligence

Around noon this morning during my lunch break home I watched the Nat Geo channel of Direct TV in the United States. The title was "South Africa" and when I began watching the camera was looking at a small water pool full of what turned out of be hundreds of tadpoles. The pool was literally packed with them and first I was not sure if those were small fish or something else. The realization that they were what I said came up later.

It was clear the little critters had hard time breathing in the pool. They all were in perpetual motion. Then all of a sudden a massive frog or a toad appeared in the view. The toad moved resolutely from dry land of the bank of the little pool across it stumping the tadpoles along the way. The toad then moved across the pool which was perhaps 10 feet in diameter and stopped at the opposite bank. It then began to move her hind legs methodically sideways. The toad was sitting on a pool bank that was a patch of wet dirt, nothing more. I stared at the motion but could not figure out what the critter was doing. In a couple of minutes it became clear. The toad was making a water passage for the tadpoles to escape and once it dug a channel deep enough that the water began escaping from the pool, the toad melancholically moved away. The little tadpoles then began swimming to a larger water pool which was behind that bank that was in fact a barrier. I wonder if the whole spectacle was smartly staged but nonetheless, how would you explained the toad's behavior? It is incredible. --AboutFace 22 (talk) 23:04, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

- It could all be instinctual. That is, the frog lays eggs in an isolated spot where they will be protected from predators, then, once they've all hatched, she breaks open the connection with a larger pool. If it's all instinct, there's no intelligence involved, just hard-wired behavior. StuRat (talk) 23:58, 25 October 2017 (UTC)

@StuRat, you disappointed me again :-) Thanks, --AboutFace 22 (talk) 00:34, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Probably not a mother toad, but an African bullfrog dad. Is this your video? In short, he doesn't want his children to die (unless it's to feed him). Filial cannibalism tries to explain this. InedibleHulk (talk) 05:16, October 26, 2017 (UTC)

- The word "want" is problematic when dealing with such lowly animals. I think of them more like computer programs, doing what they were programmed to do. Would you say a computer program "wants" to process data ? StuRat (talk) 16:37, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- In high school, I carefully dissected a frog and smashed a computer with a rock (in some order or another). The stuff inside the frog looked far more like the stuff inside me than the stuff in the computer. It was a 386, though; mother and daughterboards have come a long way, while frogs are still slow enough to be caught by the nice people who programmed early '90s models like myself. InedibleHulk (talk) 09:07, October 27, 2017 (UTC)

- In elementary school, I built a bird, tested a robot and portaged goods cross-country, all using a critter without any memory or processor at all. Nothing but a link to the queen. The queen was evil, sadly, so the entire colony was wiped out by the government. Some say her core spirit survived, though, and still commands legions of cars to this day. InedibleHulk (talk) 09:44, October 27, 2017 (UTC)

- In high school, I carefully dissected a frog and smashed a computer with a rock (in some order or another). The stuff inside the frog looked far more like the stuff inside me than the stuff in the computer. It was a 386, though; mother and daughterboards have come a long way, while frogs are still slow enough to be caught by the nice people who programmed early '90s models like myself. InedibleHulk (talk) 09:07, October 27, 2017 (UTC)

- The word "want" is problematic when dealing with such lowly animals. I think of them more like computer programs, doing what they were programmed to do. Would you say a computer program "wants" to process data ? StuRat (talk) 16:37, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Father explains how, why and when some dads are alright, and the "Non-human fatherhood" section has critter examples, including the ridiculous Darwin's frog. InedibleHulk (talk) 06:40, October 26, 2017 (UTC)

@InedibleHulk, thank you for the video. It is certainly the same episode but the one I saw on Nat Geo Wild was much better edited in comparison with this one, although here there are more details. Yes, the nature can easily encode complicated patterns of behavior in simple brains. --AboutFace 22 (talk) 21:26, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Some relevant info at Frog#Parental_care. I don't think this was staged at all, I think this is the common method of care. Here [11] is a PBS video specifically about African Bullfrogs(Pyxicephalus adspersus), and describes exactly the same behavior you describe. (P.S. Parental care is a good general search term and article, but I found the PBS video link by searching /frog brood pond/, where it was the top hit.) Parental care and its evolution is a large field of ongoing research. See here [12] for an overview, or if you have more specific questions, I can try to help if you ping me. SemanticMantis (talk) 21:50, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

@SemanticMantis, thank you but @InedibleHulk has already posted that PBS video before. Come to think of it. Somewhere in the Frog's DNA there is a gene, perhaps a few that control this behavior. How is it done? --AboutFace 22 (talk) 00:27, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- I'm not sure if we know that yet. It's complicated to even find where the instinct is in the brain, much less to figure out which genes build that area and how. StuRat (talk) 02:44, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- @AboutFace 22:, ah, sorry, @InedibleHulk:'s link is to a different place, and while I think he does good work here, I think his links would be improved if they were less cryptic :)

- As for the rest, yes, this is very complicated, complex, and in addition hard to study. But that doesn't mean we don't know a lot about it! Here are a selection of research papers that discuss genetics and evolution of parental care behavior in frogs. There are more papers out there, and some of them better, but I will limit to a few that are freely accessible. I will start with the least relevant and move towards the most.

- Here [13] is a paper about mate choice and genetic basis of color variation in a frog species. This is relevant be cause sexual selection can be a key driver of evolution of traits and behaviors, and even more so when species exhibit parental care. Near the end, they mention that the importance of parental care in that species, making it a candidate for imprinting and further self-reinforcing selection.

- Here [14] is the paper Phenotypic and Genetic Divergence in Three Species of Dart-Poison Frogs With Contrasting Parental Behavior (NB I think my URL link will expire, put the full title in to google scholar to find the pdf if you have problems). As it says, it describes how different types of poison dart frogs have genetic differences, and it suggests that they are responsible for differences in parental care. This one is highly relevant, but the story is complicated, because it also has a lot to say about extremes of color polymorphism.

- Here [15] is The evolution of female parental care in poison frogs of the genus Dendrobates; evidence from mitochondrial DNA sequences. This one uses direct genetic evidence to create a [phylogenetic tree]], showing that parental care evolved exactly once in this clade.

- Now, TL:DR: all that research gives very strong for the genetic basis of parental care behavior in frogs, and the last paper is getting very close to identifying which genes are responsible.

- I have interpreted your question as being specifically about genetic control of parental behavior in frogs. However, that is a very narrow question, and so there's less known about this particular thing, compared to the general concepts at play. If your interest is more about parental care in general, then we know lots more about that, including genetic basis, evolution, etc., but it is put together from a wide range of taxa (e.g. lots from birds and bugs). If your interest is more about genetic control of behavior in general, then again, we can get in to far more detail on that: we know remarkable things about what genes cause what behavior, and sometimes in great detail, e.g. in Drosophila. So, if you want to know more about these general issues, we can address that, but it might make sense to ask a new question in that vein. Hope this helps, SemanticMantis (talk) 15:53, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

@SemanticMantis thank you. It is very kind of you. I'm an MD but I'm involved in a different kind of research although connected to genetics. This is my only point of contact with the subject. This is my puzzle actually. Let's say this behavior is coded in the frog's DNA and it certainly is. Let's say the frog moves to the pool to release the tadpoles. How does it know that it has to move its hind legs at a certain place where the pass for them to escape is reasonably short? Is it also coded in the DNA? Then how? How does it know that it had finished the job and there is no need to dig further? Is it also coded? How? I am sure some hormones are involved in this behavior, it easy to imagine that perhaps a surge of Cortisol could start the behavior, to force the frog to move to the pool but how about the rest? --AboutFace 22 (talk) 18:01, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- David Attenborough has taken an interest in this [16]. 92.8.218.38 (talk) 18:40, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

October 26

Lead leeching out of metal

We sometimes fry things on a big slab of what seems to be carbon steel. Someone gave it to us from some plate steel place where they make stuff out of it, but not cookware. There are giant, thick sheets laying all over the place. It looks like steel or carbon steel or something. It rusts quickly but is nicely seasoned now and so is very non-stick. Do you think it's loaded with lead? Would lead leech out into the oil. Is there a way to test this? Anna Frodesiak (talk) 05:48, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Your piece of steel plate is highly, highly unlikely to contain any lead. The only steel to contain lead is free-machining steel. This is a very specialised application for steel and there is no reason for free-machining steel to be rolled into flat plate. Alloying elements in steel, such as carbon and manganese, are tightly bound within the atomic lattice and they do not leach out of the steel. Dolphin (t) 06:28, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Thank you very much, Dolphin51. :) Anna Frodesiak (talk) 08:43, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Also, with a properly seasoned iron surface, the food never touches the actual metal. --Guy Macon (talk) 15:57, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Yes, but that doesn't mean the two don't chemically interact. Iron can dissolve in the oil, and some of that gets in the food. This is actually considered a benefit of a cast iron pan, that they increase the iron content in your food. StuRat (talk) 16:33, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Note carbon steel is the (current) most common material for making woks, Wok#Carbon_steel. May have been part of why the locals knew it was good for cooking. SemanticMantis (talk) 21:39, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

Thank you, all. Your helpful information led me to create ![]() Media related to Carbon steel at Wikimedia Commons and populate it and add the commonscat to the main article.

Media related to Carbon steel at Wikimedia Commons and populate it and add the commonscat to the main article.

Now, I see ![]() Media related to Crystal structures of steel at Wikimedia Commons and wonder if any or all of those should have the carbon steel parent category added. Thoughts?

Media related to Crystal structures of steel at Wikimedia Commons and wonder if any or all of those should have the carbon steel parent category added. Thoughts?

Oh, and they want to get rid of the refdesk because it doesn't help other parts of the project. Phooey to that. You folks are wonderful and so helpful. Anna Frodesiak (talk) 01:31, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- The articles listed under “Crystal structures of steel” are all eligible to be included under “Carbon steel”. Incidentally, I notice the heading “Perlite (Steel)”. This spelling is definitely incorrect because perlite is something of interest in geology. In the context of carbon steel the spelling should be “pearlite” and is so named because of its resemblance to mother-of-pearl when viewed under a microscope. Can you tweak the spelling? Dolphin (t) 07:10, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

Small linguistic remark: You mean leaching. "Leech" with the double-e is another thing entirely. --Trovatore (talk) 08:29, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

Mass to the Moon

I understand the moon is moving away from the earth by 4 centimetres every year, how much mass would have to be added or lost for it to stay in perfect orbit? JoshMuirWikipedia (talk) 12:59, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Well, momentum is potentially unlimited, so if a well-placed alien has a sufficiently decent particle accelerator, and we wrap the Moon carefully in some sci-fi quality electrical tape to keep it from exploding, we ought to be able to knock it back where you want it with just a few protons. Of course, with current technology ... any method is impossible.

- Also note this doesn't change the tidal acceleration; it would only be modifying the present orbit. The same should be true of any one-time mass impact. Wnt (talk) 13:31, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Changing the mass wouldn't have any effect.

- Sadly WP doesn't have a clear introductory article to this. Circular orbit is about the closest. Also Kepler's third law "The square of the orbital period of a planet is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis of its orbit." was determined by observation, before Newton had worked out the gravitational theory behind it.

- For a simplified circular orbit, the period of that orbit

- where:

- is the orbital period

- is the orbit's semi-major axis in metres (altitude from the centre of the Earth, in our simplified view)

- is the gravitational constant,

- is the mass of the Earth

- So the Moon is moving away because it's slowing down. To bring it back, you'd have to speed it up. Andy Dingley (talk) 13:43, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

And the moon is slowing down because of gravitational drag due to tidal effects. Basically, some energy in the moon's motion is lost because it goes into distorting the earth's shape a bit. That lost energy causes the moon to slow down ever so slightly which causes its orbit to drift outward ever so slightly. This will not last forever, because other factors will lead to the moon-earth system becoming tidally locked so that there is no more drag on the moon. --Jayron32 15:14, 26 October 2017 (UTC)- Wait, slowing down? No that's backwards. The moon is speeding up. (Higher orbits are faster orbits.)

- It's speeding up because earth's spin (one rev/day. Fast) and the Moon's orbit (one orbit/month. Slow) are slowly converging. So the Earth is slowing its spin, while the Moon is speeding up its orbit.

- ApLundell (talk) 15:56, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Yes, of course. Damn sign conventions get me every time. My bad. --Jayron32 17:33, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- I don’t think “higher orbits are faster orbits” is right. In the formula given above by Andy, the time period T is proportional to Speed S = distance per unit time, so T = const × distance/ S where distance travelled is the circumference Equating the two expressions for T gives So higher radius a is associated with lower speed S. Loraof (talk) 17:39, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

No, he's right. It's simple orbital dynamics. I've seen Buzz Aldrin (who did his PHD thesis on the matter) discussing it in layman's terms before; but the basic principle is faster = further out. When you are in orbit, and you increase your forward velocity, you move out in orbit. More kinetic energy = further from barycenter. This is true in any rotational system (that's why electrons with more energy are at further distances from the nucleus of an atom, for much the same reason) Thus if the moon is moving outwards, it must be doing so because it is moving faster. If you slow down, you move into lower and lower orbits; if you go too slow your orbit intersects the larger object and you crash into it. --Jayron32 17:45, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- You’re describing speed between orbits. For objects in orbit with no externally imposed acceleration (other than gravity maintaining a given orbit), my math looks correct to me. Examples of orbital speed around the Sun: Earth 29.78 km/s; Mars 24.07 km/s; Jupiter 13.07 km/s. I was objecting to the statement “higher orbits are faster orbits”. Since the Moon is continually changing orbit, so to speak, part of its speed is not speed of orbit. Loraof (talk) 18:05, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- You know what, forget me again. I really shouldn't get involved in these problems. I'm such an asshole. --Jayron32 18:17, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- No, you’re not – you’re far and away the most helpful person on these ref desks. And your last comment was valuable in clarifying the difference. Thanks for all your work here! Loraof (talk) 18:24, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- You know what, forget me again. I really shouldn't get involved in these problems. I'm such an asshole. --Jayron32 18:17, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- You’re describing speed between orbits. For objects in orbit with no externally imposed acceleration (other than gravity maintaining a given orbit), my math looks correct to me. Examples of orbital speed around the Sun: Earth 29.78 km/s; Mars 24.07 km/s; Jupiter 13.07 km/s. I was objecting to the statement “higher orbits are faster orbits”. Since the Moon is continually changing orbit, so to speak, part of its speed is not speed of orbit. Loraof (talk) 18:05, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- If you add mass to Earth instead of the Moon and do it gradually then it might work. PrimeHunter (talk) 15:47, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- The moon is actually gaining energy from the rotation of the earth via the leverage of the tidal bulges (the earth's rotation drags these around so that they are ahead of the moon). Perversely (but in accordance with the virial theorem), for every one unit of energy transferred from the earth to the moon, the moon spends two units of energy in climbing higher: the one it got from the earth plus one from its own store of kinetic energy - so it ends up going slower. --catslash (talk) 16:47, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- As is always the case with questions like "what would happen to [gravitational phenomenon] if we added mass to [celestial body]", the answer is: it depends on how the mass is added. The above answer (in particular AD's) give the answer with the assumption that mass is instantaneously added with no change in any of the velocities at that instant. TigraanClick here to contact me 18:43, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

Given

- Moon's radius 1757.1 km

- Moon's mass 7.342E22 kg

the Moon's center of gravity can be moved about 4 cm closer to Earth by adding a mass (7.342E22 x 0.04)/1732.1E3 = 1.70E15 kg on the side facing Earth, taking care to match velocities before contact. Continual deliveries of 2E11 kg every hour (the US annual waste production) might be a nice way to keep the Moon's orbit constant. Blooteuth (talk) 19:12, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- People think the moon is speeding up because the lunar month is getting shorter. What is actually happening is that the moon is slowing down but our clocks are also slowing down because of the tidal drag (as measured by successive transits of the meridian by the sun, mean solar time). The clocks are slowing faster than the moon, so it appears to be going faster. 92.8.218.38 (talk) 14:15, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

Hydraulic motors

Why are hydraulic motors not more popular for vehicles? Hydraulic pump and motor pairs seems to be a very efficient way to transmit motive force from an engine to wheels. It eliminates friction losses from multiple gears, shafts and other moving parts in conventional transmission systems, and also weighs much less. I get the idea I'm missing information about one or more major disadvantages that explain why it's so rare. Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 19:01, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Hydraulic linkages are indeed efficient and are employed in automatic transmissions. But your vehicle will need a prime mover i.e. a motor that converts energy from a source energy into mechanical energy. What source energy would you like to pay for? Blooteuth (talk) 19:25, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Blooteuth I'd imagine an internal combustion engine driving a hydraulic pump would be the most obvious prime mover. The hydraulic linkage within a conventional transmission just one small component, I'm wondering why hydraulics are/were not used far more to basically eliminate almost the entire mechanical gear-and-shaft based drivetrain between engine and wheels? In recent years of course eletric drive has become far more efficient with hybrid IC/battery or even pure battery driven vehicles becomming more common. Hydraulics just seems to have never been considered a viable replacement for the conventional drivetrain. Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 19:43, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- Don't confuse hydrostatic transmission with hydrodynamic. Hydrostatic transmissions (pump and motor) are limited in power, speed and efficiency. They're mostly used when controllability is important, or high force vs. speed. They can also make accurate positioning mechanisms, as well as continuous rotation.

- Hydrodynamic transmissions are those involving fluid couplings, torque converters and the transmissions of diesel-hydraulic locomotives are quite different. They can transmit high powers (multi-thousand horsepower) at high speeds, and are lighter, simpler and more compact than comparable diesel-electric transmissions. Andy Dingley (talk) 20:11, 26 October 2017 (UTC)

- One problem with hydraulics is that they behave differently at different temperatures. Fluid viscosity changes, volume changes, etc. Thus, a cold vehicle would drive very differently than a hot one. There are ways to compensate for this, within limits. StuRat (talk) 03:08, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Hydraulic fluids in power transmission systems operate at a fairly constant temperature, set by their cooling systems and thermostats. They are heated by use plenty to rise above ambient. If they're in a cold climate, they may be pre-circulated beforehand, just to warm them. Andy Dingley (talk) 13:58, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

I found Human Friendly Transmission, used by Honda in a few motorcycles. Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 06:16, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- That is a continuously variable transmission (i.e. a continuous-ratio gearbox), which makes up only a small part of the drivetrain. An important part of OP's question is why isn't most / all of the drivetrain made by hydro links, which presumably have less friction (hence power losses) than mechanical drivetrains. (I do not have a clue.) TigraanClick here to contact me 11:26, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- In case there's some confusion, Roger is the OP. Nil Einne (talk) 11:37, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

October 27

Zero living diet

Are there any foods that have never lived? Meaning, no animals, plants bacteria etc. Would it be possible to live on such diet?

- Water... most people might last a few weeks. Roger (Dodger67) (talk) 06:18, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Only prokaryotes can do that, they have the enzymes to take in abiotic chemical compounds and make all the stuff they need. Eukaryotes are dependent on other organisms for their survival, e.g. they can't make vitamin B12, they don't have the enzymes for nitrogen fixation either, so they are dependent on prokaryotes for their amino-acids. Count Iblis (talk) 06:32, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- It is possible to make synthetic fatty acids [17] - mercifully, it doesn't seem to have caught on; I guess the odd-numbered ones did not even meet up to the standards of the trans fat era. Synthetic sugars are harder. [18] Vitamin supplements are an issue, yet some are produced synthetically. There is no theoretical reason why such a diet cannot be produced (though you might need to go off-planet to find carbon you are somewhat confident 'never lived'), but it would be exceedingly difficult, so I would not expect the first test subjects to live long. Also note that ethane, present on Titan, is metabolized by the rat [19] so at least some "foods" presently exist that match this criterion, though it would be poorly nutritious and a bit over-chilled on the palate. Wnt (talk) 11:03, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- There are many kinds of extremophiles that live on, for example, organic chemicals that seep into the oceans from mid-oceanic hydrothermal vents. Chemosynthesis would be the term. As to the main question, no, it is not possible for you as a person to live on food which has never lived. Excepting certain dietary minerals, which do not provide energy to your body, food entails life. All food must have been living at some time previous, for any reasonable definition of "previous". Some foods are currently living. Indeed, many raw plant foods we eat are alive while we consume them. --Jayron32 11:06, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Can we say that plants have a diet of non-living food? I mean they just need water and minerals from the ground, CO2 in the atmosphere, and sunlight for energy. I guess the question is more about whether you accept that plants "eat" at all.— Preceding unsigned comment added by Lgriot (talk • contribs)

- Well, that's it. We need to define "eating". I mean, I would define that as ingesting a substance for the purpose of obtaining energy and building materials. There are other forms of ingesting we do (drinking, smoking, taking medicine or vitamins) which we don't call eating. Wikipedia's article on eating specifically excludes most plants, since plants are autotrophs. If you change the definition of eating, then sure, you can define plants as eating. But really, if you can just change the definitions of words to fit your needs, you can "prove" anything with those words. --Jayron32 14:42, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Note that plants depend on bacteria to do the nitrogen fixation necessary to make amino acids. Count Iblis (talk) 18:00, 27 October 2017 (UTC)

- Can we say that plants have a diet of non-living food? I mean they just need water and minerals from the ground, CO2 in the atmosphere, and sunlight for energy. I guess the question is more about whether you accept that plants "eat" at all.— Preceding unsigned comment added by Lgriot (talk • contribs)

- The answers to a similar question from 2014, Wikipedia:Reference_desk/Archives/Humanities/2014_August_14#Non-living_food, may be of interest.--Wikimedes (talk) 18:39, 27 October 2017 (UTC)