Thai language

| Thai | |

|---|---|

| Siamese | |

| ภาษาไทย Phasa Thai | |

| Pronunciation | [pʰāːsǎː tʰāj] |

| Region | Thailand Cambodia (Koh Kong District) Malaysia |

| Ethnicity | Thai and Thai Chinese |

Native speakers | 20 to 36 million (2000)[1] 44 million L2 speakers with Lanna, Isan, Southern Thai, Northern Khmer and Lao (2001)[1] |

Kra–Dai

| |

| Thai script Thai Braille | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Thailand |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Royal Society of Thailand |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | th |

| ISO 639-2 | tha |

| ISO 639-3 | tha |

| Glottolog | thai1261 |

| Linguasphere | 47-AAA-b |

| |

Thai,[a] Central Thai[3] (historically Siamese;[b] Template:Lang-th), is the sole official and national language of Thailand and the first language of the Central Thai people[c] and vast majority of Thai Chinese. It is a member of the Tai group of the Kra–Dai language family. Over half of Thai vocabulary is derived from or borrowed from Pali, Sanskrit, Mon and Old Khmer. It is a tonal and analytic language, similar to Chinese and Vietnamese.

Thai has a complex orthography and system of relational markers. Spoken Thai is mutually intelligible with Lao and Isan, fellow Southwestern Tai languages, to a significantly high degree where its speakers are able to effectively communicate each speaking their respective language. These languages are written with slightly different scripts but are linguistically similar and effectively form a dialect continuum.[4]

Varieties and related languages

Thai is the official language of Thailand, natively spoken by, according to Ethnologue, over 20 million people (2000). In reality, the number of native Thai speakers is likely to be much higher, since the Thai citizens throughout the central Thailand learn it as their first language while the populations of western and eastern parts of Thailand, which had since ancient time formed the core territory of Siam, also speak central Thai as their first language. Moreover, most Thais in the northern and the northeastern (Isaan) parts of the country today are bilingual speakers of Central Thai and their respective regional dialects due to the fact that (Central) Thai is the language of television, education, news reporting, and all forms of media.[5] A recent research finds that the speakers of Northern Thai language (or Kham Mueang) have become so few, as most people in northern Thailand now invariably speak standard Thai, such that they are now using mostly central Thai words and seasoning their speech only with "kham mueang" accent. [6] Standard Thai is based on Ayutthaya dialect,[d] and register in the educated classes.[7] In addition to Central Thai, Thailand is home to other related Tai languages. Although some linguists classify these dialects as related but distinct languages, there is a high degree of mutual intelligibility between these regional dialects/languages. Nonetheless, it is often claimed that the language policy of the Thai government[citation needed] has shaped the dominant view that these languages are only regional variants or dialects of the "same" Thai language, or as "different kinds of Thai".[8]

Dialects

Central Plains Thai

- Eastern Central Plains.

- Ayutthaya dialect (Standard Thai, Outer Bangkok), native spoken in encircle area of Bangkok such as Ayutthaya, Ang Thong, Lopburi, Saraburi, Nakhon Nayok, Nonthaburi, Pathum Thani, Samut Sakhon and Samut Prakan Provinces, Eastern and Northern Bangkok. Although this dialect is standard form and sole use in education system, however this dialect are not public especially in metropolitan area, in media can found on Thai Royal News only.

- Eastern dialect, spoken in Chanthaburi, Trat, Sa Kaeo, Prachinburi (except Muang Prachinburi, Si Maha Phot, Si Mahosot and Kabin Buri Districts speak Chonburi dialect and Isan), Chachoengsao (except Mueang Paet Riu, Phanom Sarakham, Bang Khla, Ban Pho and Bang Pakong Districts speak Chonburi dialect), part of Chonburi and part of Koh Kong Province of Cambodia.

- Thonburi dialect (also called Bangkok dialect), spoken in Thonburi side of Bangkok. Have some Portuguese and Persian influences.

- Vientiane Central Thai, spoken in Tha Bo District and some place in Ratchaburi Province. Very related to Ayutthaya dialect and sometimes can classified as Ayutthaya dialect.

- Western Central Plains.

- Suphanburi dialect, spoken in Suphan Buri, Sing Buri, Nakhon Pathom, part of Samut Songkhram, part of Ratchaburi and some place in Rayong Provinces. This dialect is standard form in Ayutthaya Kingdom, but today remain in Khon only.

- Kanchanaburi dialect, spoken in Kanchanaburi. Very related to Suphanburi dialect and sometimes can classified as Suphanburi dialect.

- Rayong dialect, spoken in Rayong Province, Bang Lamung (outside Pattaya City), Sattahip and part of Si Racha Districts

Capital Core Thai

- Core area.

- Krung Thep dialect (also called Phra Nakhon dialect), native spoken in core area of Phra Nakhon side in Bangkok (but not native in Eastern and Northern Bangkok which speak Standard Thai), however this dialect is common use as an entire metropolitan area. Common Media in Thailand use this dialect.

- Chonburi dialect (called Paet Riu dialect in Chachoengsao Province), spoken in most upper part of Chonburi Province (also in Pattaya), Mueang Paet Riu, Phanom Sarakham, Bang Khla, Ban Pho and Bang Pakong Districts in Chachoengsao, Mueang Prachinburi, Si Maha Phot, Si Mahosot and Kabin Buri Districts in Prachinburi, part of Chanthaburi Provinces, and Aranyaprathet District.

- Enclave areas[e]

- Nangrong dialect, spoke by Teochew trader in Nang Rong District. This dialect enclaved by Isan language, Northern Khmer language and Kuy language.

- Photharam dialect, language enclave in Photharam, Ban Pong and Mueang Ratchaburi districts, but classified as Capital dialect. This dialect enclaved by Ratchburi dialect.

- Hatyai dialect, spoke by non-Peranakan Chinese origin (particularly Teochews) in Hat Yai District (Peranakans speak Southern Thai language), Very high Teochew and some Southern Thai influences, Southern Thai language called Leang Ka Luang (Template:Lang-th). This dialect enclaved by Southern Thai language.

- Bandon dialect, spoke by non-Peranakan Chinese origin (particularly Teochews) in Bandon District, very similar with Hatyai dialect and also enclaved by Southern Thai language.

- Betong dialect, spoke by non-Peranakan Chinese origin (particularly Cantonese) in Patani area, Some Cantonese and Teochew influences and high Southern Thai and Yawi language influences. This dialect enclaved by Southern Thai language and Yawi language.

Upper Central Thai (Sukhothai dialects)

- New Sukhothai dialect, spoken in Sukhothai, Kamphaeng Phet, Phichit and part of Tak Provinces. High Northern Thai influence.

- Phitsanulok dialect, or old Sukhothai dialect, spoken in Phitsanulok, Phetchabun and part of Uttaradit Provinces. This dialect is standard form in vassal state of Phitsanuloksongkwae

- Pak Nam Pho dialect, spoken in Nakhon Sawan, Uthai Thani, Chainat, part of Phichit and part of Kamphaeng Phet Provinces.

Southwestern Thai (Tenasserim Thai)

- Ratchburi dialect, spoken in Ratchaburi and most area in Samut Songkhram Provinces.

- Prippri dialect, spoken in Phetchaburi and Prachuap Khiri Khan Provinces (except Thap Sakae, Bang Saphan and Bang Saphan Noi Districts).

Khorat Thai

Related languages

- Isan (Northeastern Thai), the language of the Isan region of Thailand, a collective term for the various Lao dialects spoken in Thailand that show some Central Thai influences, which is written with the Thai script. It is spoken by about 20 million people. Thais from both inside and outside the Isan region often simply call this variant "Lao" when speaking informally.

- Northern Thai (Phasa Nuea, Lanna, Kam Mueang, or Thai Yuan), spoken by about 6 million (1983) in the formerly independent kingdom of Lanna (Chiang Mai). Shares strong similarities with Lao to the point that in the past the Siamese Thais referred to it as Lao.

- Southern Thai (Thai Tai, Pak Tai, or Dambro), spoken by about 4.5 million (2006)

- Phu Thai, spoken by about half a million around Nakhon Phanom Province, and 300,000 more in Laos and Vietnam (2006).

- Phuan, spoken by 200,000 in central Thailand and Isan, and 100,000 more in northern Laos (2006).

- Shan (Thai Luang, Tai Long, Thai Yai), spoken by about 100,000 in north-west Thailand along the border with the Shan States of Burma, and by 3.2 million in Burma (2006).

- Lü (Lue, Yong, Dai), spoken by about 1,000,000 in northern Thailand, and 600,000 more in Sipsong Panna of China, Burma, and Laos (1981–2000).

- Nyaw language, spoken by 50,000 in Nakhon Phanom Province, Sakhon Nakhon Province, Udon Thani Province of Northeast Thailand (1990).

- Song, spoken by about 30,000 in central and northern Thailand (2000).

Registers

Central Thai is composed of several distinct registers, forms for different social contexts:

- Street or Common Thai (Template:Wiktth, phasa phut, spoken Thai): informal, without polite terms of address, as used between close relatives and friends.

- Elegant or Formal Thai (Template:Wiktth, phasa khian, written Thai): official and written version, includes respectful terms of address; used in simplified form in newspapers.

- Rhetorical Thai: used for public speaking.

- Religious Thai: (heavily influenced by Sanskrit and Pāli) used when discussing Buddhism or addressing monks.

- Royal Thai (ราชาศัพท์, racha sap): influenced by Khmer, this is used when addressing members of the royal family or describing their activities. (See Monarchy of Thailand § Rachasap.)

Most Thais can speak and understand all of these contexts. Street and Elegant Thai are the basis of all conversations.[9][citation needed] Rhetorical, religious, and royal Thai are taught in schools as the national curriculum.

monchai phumathuek roit6399-034458985 ( ร.9)640-95opofgklusasuiniteij-0823kmj-0-00i34i0-0i-06hi0io-0-9023pi;j;l;lkj;l'v;c';';pfylul';l,lt[illfffplyulo][polk073=---76-=0jk;yho65p[;,k;/ bv';;;klokpo6o7po450-9259-08-04325-0-064pokklk07okp-0fdghfcg060960349k;l,b,b,mp;t095t40oi-09436994090909vk;l,j5-69u0cg0v9g9t0de-=rfg09090469049564296inp098706-87-0=675=-06304965-0l;';lp[hlkjt[foi0976iklk0934-06-087-5i-mnpl-[4570-09-09y;lb,c[y7[-0ujpln-04yupolbl;[675463-46906uk[m;l9870-8-09043oi09=-9-9=908959olkbp06toi c09b09fv9h0h0845046945=-9909989-045090-9hlk;lblhuj9kkjmuikoho994950909-yh[po[df9=4309-099yh;l,' 0650699569507-0kjjl[p;.';.;jkh;l'jkhg;;lk[nm;,'./nb.,m,/./bn;l,kj;./m,nb;[';jk'v;hkjglk;;.,m./,.m'.;k;l/.[;jh;k.b'n[pko6439-00069-0hkkhg-0096jkffncnbvhjeh348u09490090943589ojmvnbmkjb ti4509829035pokbm 43089-0--=0=-9=0-90780974876y0-9gf0h9-090909n-cv-0vn-09m90809gd8-0 -0i-0-d098hp[[-08-0-009klkdp54450pkolooh';df;po9-=0-495-klnko0oyikp[of0-94098-0960-ogh[poj9etlhpl.b[0p34096luj0llkousjk560bpoijusan,p509=-043=-[pnit45poh909809bkl;lxp98-4pjn,6500y54909gfgg450ghff7uopip[u4930

Script

Many scholars believe[citation needed] that the Thai script is derived from the Khmer script. Certainly the numbers were lifted directly from Khmer. The language and its script are closely related to the Lao language and script. Most literate Lao are able to read and understand Thai, as more than half of the Thai vocabulary, grammar, intonation, vowels and so forth are common with the Lao language.

Much like the Burmese adopted the Mon script (which also has Indic origins), the Thais adopted and modified the Khmer script to create their own writing system. While in Thai the pronunciation can largely be inferred from the script, the orthography is complex, with silent letters to preserve original spellings and many letters representing the same sound. While the oldest known inscription in the Khmer language dates from 611 CE, inscriptions in Thai writing began to appear around 1292 CE. Notable features include:

- It is an abugida script, in which the implicit vowel is a short /a/ in a syllable without final consonant and a short /o/ in a syllable with final consonant.

- Tone markers, if present, are placed above the final onset consonant of the syllable.

- Vowels sounding after an initial consonant can be located before, after, above or below the consonant, or in a combination of these positions.

Transcription

There is no universally applied method for transcribing Thai into the Latin alphabet. For example, the name of the main airport is transcribed variously as Suvarnabhumi, Suwannaphum, or Suwunnapoom. Guide books, textbooks and dictionaries may each follow different systems. For this reason, most language courses recommend that learners master the Thai script.[citation needed]

Official standards are the Royal Thai General System of Transcription (RTGS), published by the Royal Institute of Thailand,[10] and the almost identical ISO 11940-2 defined by the International Organization for Standardization. The RTGS system is increasingly used in Thailand by central and local governments, especially for road signs.[11] Its main drawbacks are that it does not indicate tone or vowel length. As the system is based on pronunciation, not orthography, reconstruction of Thai spelling from RTGS romanisation is not possible.

Transliteration

The ISO published an international standard for the transliteration of Thai into Roman script in September 2003 (ISO 11940).[12] By adding diacritics to the Latin letters, it makes the transcription reversible, making it a true transliteration. Notably, this system is used by Google Translate, although it seems not to appear in many other contexts, such as textbooks and other instructional media. This may be because the particular problems of writing Thai for foreigners, including silent letters and placement of vowel markers, decrease the usefulness of literal transliteration.

Phonology

Consonants

Initials

Thai distinguishes three voice-onset times among plosive and affricate consonants:

Where English makes a distinction between voiced /b/ and unvoiced aspirated /pʰ/, Thai distinguishes a third sound - the unvoiced, unaspirated /p/ that occurs in English only as an allophone of /pʰ/, for example after an /s/ as in the sound of the p in "spin". There is similarly an alveolar /d/, /t/, /tʰ/ triplet in Thai. In the velar series there is a /k/, /kʰ/ pair and in the postalveolar series a /t͡ɕ/, /t͡ɕʰ/ pair, but the language lacks the corresponding voiced sounds /ɡ/ and /dʑ/. (In loanwords from English, English /ɡ/ and /d͡ʒ/ are borrowed as the tenuis stops /k/ and /t͡ɕ/.)

In each cell below, the first line indicates International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA), the second indicates the Thai characters in initial position (several letters appearing in the same box have identical pronunciation). Note also that ห, one of the two h letters, is also used to help write certain tones (described below).

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | [m] ม |

[n] ณ,น |

[ŋ] ง |

|||

| Plosive | voiced | [b] บ |

[d] ฎ,ด |

|||

| tenuis | [p] ป |

[t] ฏ,ต |

[tɕ] จ |

[k] ก |

[ʔ] อ** | |

| aspirated | [pʰ] ผ,พ,ภ |

[tʰ] ฐ,ฑ,ฒ,ถ,ท,ธ |

[tɕʰ] ฉ,ช,ฌ |

[kʰ] ข,ฃ,ค,ฅ,ฆ* |

||

| Fricative | [f] ฝ,ฟ |

[s] ซ,ศ,ษ,ส |

[h] ห,ฮ | |||

| Approximant | [l] ล,ฬ |

[j] ญ,ย |

[w] ว |

|||

| Trill | [r] ร |

|||||

- * ฃ and ฅ are no longer used. Thus, modern Thai is said to have 42 consonant letters.

- ** Initial อ is silent and therefore considered as a glottal stop.

Finals

Although the overall 44 Thai consonant letters provide 21 sounds in case of initials, the case for finals is different. For finals, only eight sounds, as well as no sound, called mātrā (Template:Wiktth) are used. To demonstrate, at the end of a syllable, บ (/b/) and ด (/d/) are devoiced, becoming pronounced as /p/ and /t/ respectively. Additionally, all plosive sounds are unreleased. Hence, final /p/, /t/, and /k/ sounds are pronounced as [p̚], [t̚], and [k̚] respectively.

Of the consonant letters, excluding the disused ฃ and ฅ, six (ฉ ผ ฝ ห อ ฮ) cannot be used as a final and the other 36 are grouped as following.

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | [m] ม |

[n] ญ,ณ,น,ร,ล,ฬ |

[ŋ] ง |

||

| Plosive | [p] บ,ป,พ,ฟ,ภ |

[t] จ,ช,ซ,ฌ,ฎ,ฏ,ฐ,ฑ, ฒ,ด,ต,ถ,ท,ธ,ศ,ษ,ส |

[k] ก,ข,ค,ฆ |

[ʔ]* | |

| Approximant | [w] ว |

[j] ย |

- * The glottal plosive appears at the end when no final follows a short vowel

Clusters

In Thai, each syllable in a word is considered separate from the others, so combinations of consonants from adjacent syllables are never recognised as a cluster. Thai has phonotactical constraints that define permissible syllable structure, consonant clusters, and vowel sequences. Original Thai vocabulary introduces only 11 combined consonantal patterns:

- /kr/ (กร), /kl/ (กล), /kw/ (กว)

- /kʰr/ (ขร,คร), /kʰl/ (ขล,คล), /kʰw/ (ขว,คว)

- /pr/ (ปร), /pl/ (ปล)

- /pʰr/ (พร), /pʰl/ (ผล,พล)

- /tr/ (ตร)

The number of clusters increases when a few more combinations are presented in loanwords such as /tʰr/ (ทร) in Template:Wiktth (/intʰraː/, from Sanskrit indrā) or /fr/ (ฟร) in Template:Wiktth (/friː/, from English free); however, it can be observed that Thai language supports only those in initial position, with either /r/, /l/, or /w/ as the second consonant sound and not more than two sounds at a time.

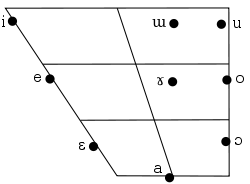

Vowels

The vowel nuclei of the Thai language are given in the following table. The top entry in every cell is the symbol from the International Phonetic Alphabet, the second entry gives the spelling in the Thai alphabet, where a dash (–) indicates the position of the initial consonant after which the vowel is pronounced. A second dash indicates that a final consonant must follow.

| Front | Back | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unrounded | Rounded | |||||

| short | long | short | long | short | long | |

| High | /i/ -ิ |

/iː/ -ี |

/ɯ/ -ึ |

/ɯː/ -ื- |

/u/ -ุ |

/uː/ -ู |

| Mid | /e/ เ-ะ |

/eː/ เ- |

/ɤ/ เ-อะ |

/ɤː/ เ-อ |

/o/ โ-ะ |

/oː/ โ- |

| Low | /ɛ/ แ-ะ |

/ɛː/ แ- |

/a/ -ะ, -ั- |

/aː/ -า |

/ɔ/ เ-าะ |

/ɔː/ -อ |

The vowels each exist in long-short pairs: these are distinct phonemes forming unrelated words in Thai,[13] but usually transliterated the same: เขา (khao) means "he" or "she", while ขาว (khao) means "white".

The long-short pairs are as follows:

| Long | Short | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thai | IPA | Example | Thai | IPA | Example | ||||

| –า | /aː/ | Template:Wiktth | /fǎːn/ | 'to slice' | –ะ | /a/ | Template:Wiktth | /fǎn/ | 'to dream' |

| –ี | /iː/ | Template:Wiktth | /krìːt/ | 'to cut' | –ิ | /i/ | Template:Wiktth | /krìt/ | 'kris' |

| –ู | /uː/ | Template:Wiktth | /sùːt/ | 'to inhale' | –ุ | /u/ | Template:Wiktth | /sùt/ | 'rearmost' |

| เ– | /eː/ | Template:Wiktth | /ʔēːn/ | 'to recline' | เ–ะ | /e/ | Template:Wiktth | /ʔēn/ | 'tendon, ligament' |

| แ– | /ɛː/ | Template:Wiktth | /pʰɛ́ː/ | 'to be defeated' | แ–ะ | /ɛ/ | Template:Wiktth | /pʰɛ́ʔ/ | 'goat' |

| –ื- | /ɯː/ | Template:Wiktth | /kʰlɯ̂ːn/ | 'wave' | –ึ | /ɯ/ | Template:Wiktth | /kʰɯ̂n/ | 'to go up' |

| เ–อ | /ɤː/ | Template:Wiktth | /dɤ̄ːn/ | 'to walk' | เ–อะ | /ɤ/ | Template:Wiktth | /ŋɤ̄n/ | 'silver' |

| โ– | /oː/ | Template:Wiktth | /kʰôːn/ | 'to fell' | โ–ะ | /o/ | Template:Wiktth | /kʰôn/ | 'thick (soup)' |

| –อ | /ɔː/ | Template:Wiktth | /klɔːŋ/ | 'drum' | เ–าะ | /ɔ/ | Template:Wiktth | /klɔ̀ŋ/ | 'box' |

There are also opening and closing diphthongs in Thai, which Tingsabadh & Abramson (1993) analyze as underlyingly /Vj/ and /Vw/. For purposes of determining tone, those marked with an asterisk are sometimes classified as long:

| Long | Short | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Thai script | IPA | Thai script | IPA |

| –าย | /aːj/ | ไ–*, ใ–*, ไ–ย, -ัย | /aj/ |

| –าว | /aːw/ | เ–า* | /aw/ |

| เ–ีย | /iːə/ | เ–ียะ | /iə/ |

| – | – | –ิว | /iw/ |

| –ัว | /uːə/ | –ัวะ | /uə/ |

| –ูย | /uːj/ | –ุย | /uj/ |

| เ–ว | /eːw/ | เ–็ว | /ew/ |

| แ–ว | /ɛːw/ | – | – |

| เ–ือ | /ɯːə/ | เ–ือะ | /ɯə/ |

| เ–ย | /ɤːj/ | – | – |

| –อย | /ɔːj/ | – | – |

| โ–ย | /oːj/ | – | – |

Additionally, there are three triphthongs. For purposes of determining tone, those marked with an asterisk are sometimes classified as long:

| Thai script | IPA |

|---|---|

| เ–ียว* | /iəw/ |

| –วย* | /uəj/ |

| เ–ือย* | /ɯəj/ |

Tones

There are five phonemic tones: mid, low, falling, high, and rising, sometimes referred to in older reference works as rectus, gravis, circumflexus, altus, and demissus, respectively.[14] The table shows an example of both the phonemic tones and their phonetic realization, in the IPA.

Notes:

- Recent studies reported a change of the high level to a mid rising among youngsters.[15][16]

- The full complement of tones exists only in so-called "live syllables", those that end in a long vowel or a sonorant (/m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /j/, /w/).

- For "dead syllables", those that end in a plosive (/p/, /t/, /k/) or in a short vowel, only three tonal distinctions are possible: low, high, and falling. Because syllables analyzed as ending in a short vowel may have a final glottal stop (especially in slower speech), all "dead syllables" are phonetically checked, and have the reduced tonal inventory characteristic of checked syllables.

Unchecked syllables

| Tone | Thai | Example | Phonemic | Phonetic | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mid | สามัญ | คา | /kʰāː/ | [kʰaː˧] | stick |

| low | เอก | ข่า | /kʰàː/ | [kʰaː˨˩] or [kʰaː˩] | galangal |

| falling | โท | ค่า | /kʰâː/ | [kʰaː˥˩] | value |

| high | ตรี | ค้า | /kʰáː/ | [kʰaː˦˥] or [kʰaː˥] | to trade |

| rising | จัตวา | ขา | /kʰǎː/ | [kʰaː˩˩˦] or [kʰaː˩˦] | leg |

Checked syllables

| Tone | Thai | Example | Phonemic | Phonetic | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low (short vowel) | เอก | หมัก | /màk/ | [mak̚˨˩] | marinate |

| low (long vowel) | เอก | หมาก | /màːk/ | [maːk̚˨˩] | areca nut, areca palm, betel, fruit |

| high | ตรี | มัก | /mák/ | [mak̚˦˥] | habitually, likely to |

| falling | โท | มาก | /mâːk/ | [maːk̚˥˩] | a lot, abundance, many |

In some English loanwords, closed syllables with long vowel ending in an obstruent sound, have high tone, and closed syllables with short vowel ending in an obstruent sound have falling tone.

| Tone | Thai | Example | Phonemic | Phonetic | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| high | ตรี | มาร์ก | /máːk/ | [maːk̚˦˥] | Marc, Mark |

| high | ตรี | สตาร์ต | /sa.táːt/ | [sa.taːt̚˦˥] | start |

| high | ตรี | บาส(เกตบอล) | /báːt(.kêt.bɔ̄n)/1 | [baːt̚˦˥(.ket̚˥˩.bɔn˧)] | basketball |

| falling | โท | เมกอัป | /méːk.ʔâp/ | [meːk̚˦˥.ʔap̚˥] | make-up |

1 May be /báːs.kêt.bɔ̄l/ in educated speech.

Grammar

From the perspective of linguistic typology, Thai can be considered to be an analytic language. The word order is subject–verb–object, although the subject is often omitted. Thai pronouns are selected according to the gender and relative status of speaker and audience.

Adjectives and adverbs

There is no morphological distinction between adverbs and adjectives. Many words can be used in either function. They follow the word they modify, which may be a noun, verb, or another adjective or adverb.

- คนอ้วน (khon uan, [kʰon ʔûən ]) a fat person

- คนที่อ้วนเร็ว (khon thi uan reo, [khon tʰîː ʔûən rew]) a person who became fat quickly

Comparatives take the form "A X กว่า B" (kwa, [kwàː]), A is more X than B. The superlative is expressed as "A X ที่สุด" (thi sut, [tʰîːsùt]), A is most X.

- เขาอ้วนกว่าฉัน (khao uan kwa chan, [kʰǎw ʔûən kwàː tɕ͡ʰǎn]) S/he is fatter than me.

- เขาอ้วนที่สุด (khao uan thi sut, [kʰǎw ʔûən tʰîːsùt]) S/he is the fattest (of all).

Because adjectives can be used as complete predicates, many words used to indicate tense in verbs (see Verbs:Tense below) may be used to describe adjectives.

- ฉันหิว (chan hiu, [tɕ͡ʰǎn hǐw]) I am hungry.

- ฉันจะหิว (chan cha hiu, [tɕ͡ʰǎn tɕ͡àʔ hǐw]) I will be hungry.

- ฉันกำลังหิว (chan kamlang hiu, [tɕ͡ʰǎn kamlaŋ hǐw]) I am hungry right now.

- ฉันหิวแล้ว (chan hiu laeo, [tɕ͡ʰǎn hǐw lɛ́ːw]) I am already hungry.

- Remark ฉันหิวแล้ว mostly means "I am hungry right now" because normally, แล้ว ([lɛ́ːw]) marks the change of a state, but แล้ว has many other uses as well. For example, in the sentence, แล้วเธอจะไปไหน ([lɛ́ːw tʰɤː tɕ͡àʔ paj nǎj]): So where are you going?, แล้ว ([lɛ́ːw]) is used as a discourse particle.

Verbs

Verbs do not inflect. They do not change with person, tense, voice, mood, or number; nor are there any participles.

- ฉันตีเขา (chan ti khao, [t͡ɕʰǎn tiː kʰǎw]), I hit him.

- เขาตีฉัน (khao ti chan, [kʰǎw tiː t͡ɕʰǎn]), He hit me.

The passive voice is indicated by the insertion of ถูก (thuk, [tʰùːk]) before the verb. For example:

- เขาถูกตี (khao thuk ti, [kʰǎw tʰùːk tiː]), He is hit. This describes an action that is out of the receiver's control and, thus, conveys suffering.

To convey the opposite sense, a sense of having an opportunity arrive, ได้ (dai, [dâj], can) is used. For example:

- เขาจะได้ไปเที่ยวเมืองลาว (khao cha dai pai thiao mueang lao, [kʰǎw t͡ɕaʔ dâj paj tʰîow mɯːəŋ laːw]), He gets to visit Laos.

Note, dai ([dâj] and [dâːj]), though both spelled ได้, convey two separate meanings. The short vowel dai ([dâj]) conveys an opportunity has arisen and is placed before the verb. The long vowel dai ([dâːj]) is placed after the verb and conveys the idea that one has been given permission or one has the ability to do something. Also see the past tense below.

- เขาตีได้ (khao ti dai, [kʰǎw tiː dâːj]), He is/was allowed to hit or He is/was able to hit

Negation is indicated by placing ไม่ (mai,[mâj] not) before the verb.

- เขาไม่ตี, (khao mai ti) He is not hitting. or He doesn't hit.

Tense is conveyed by tense markers before or after the verb.

- Present can be indicated by กำลัง (kamlang, [kamlaŋ], currently) before the verb for ongoing action (like English -ing form), by อยู่ (yu, [jùː]) after the verb, or by both. For example:

- เขากำลังวิ่ง (khao kamlang wing, [kʰǎw kamlaŋ wîŋ]), or

- เขาวิ่งอยู่ (khao wing yu, [kʰǎw wîŋ jùː]), or

- เขากำลังวิ่งอยู่ (khao kamlang wing yu, [kʰǎw kamlaŋ wîŋ jùː]), He is running.

- Future can be indicated by จะ (cha, [t͡ɕaʔ], "will") before the verb or by a time expression indicating the future. For example:

- เขาจะวิ่ง (khao cha wing, [kʰǎw t͡ɕaʔ wîŋ]), He will run or He is going to run.

- Past can be indicated by ได้ (dai, [dâːj], "did") before the verb or by a time expression indicating the past. However, แล้ว (laeo, :[lɛ́ːw], already) is often used to indicate the past tense by being placed behind the verb. Or, both ได้ and แล้ว are put together to form the past tense expression. For example:

- เขาได้กิน (khao dai kin, [kʰǎw dâːj kin]), He ate.

- เขากินแล้ว (khao kin laeo, [kʰǎw kin lɛ́ːw], He has eaten.

- เขาได้กินแล้ว (khao dai kin laeo, [kʰǎw dâːj kin lɛ́ːw]), He's already eaten.

Tense markers are not required.

- ฉันกินที่นั่น (chan kin thinan, [t͡ɕʰǎn kin tʰîːnân]), I eat there.

- ฉันกินที่นั่นเมื่อวาน (chan kin thinan mueawan), I ate there yesterday.

- ฉันกินที่นั่นพรุ่งนี้ (chan kin thinan phrungni), I'll eat there tomorrow.

Thai exhibits serial verb constructions, where verbs are strung together. Some word combinations are common and may be considered set phrases.

- เขาไปกินข้าว (khao pai kin khao, [kʰǎw paj kin kʰâːw]) He went out to eat, literally He go eat rice

- ฉันฟังไม่เข้าใจ (chan fang mai khao chai, [tɕ͡ʰǎn faŋ mâj kʰâw tɕ͡aj]) I don't understand what was said, literally I listen not understand

- เข้ามา (khao ma, [kʰâw maː]) Come in, literally enter come

- ออกไป! (ok pai, [ʔɔ̀ːk paj]) Leave! or Get out!, literally exit go

Nouns

Nouns are uninflected and have no gender; there are no articles.

Nouns are neither singular nor plural. Some specific nouns are reduplicated to form collectives: เด็ก (dek, child) is often repeated as เด็ก ๆ (dek dek) to refer to a group of children. The word พวก (phuak, [pʰûak]) may be used as a prefix of a noun or pronoun as a collective to pluralize or emphasise the following word. (พวกผม, phuak phom, [pʰûak pʰǒm], we, masculine; พวกเรา phuak rao, [pʰûak raw], emphasised we; พวกหมา phuak ma, (the) dogs). Plurals are expressed by adding classifiers, used as measure words (ลักษณนาม), in the form of noun-number-classifier (ครูห้าคน, "teacher five person" for "five teachers"). While in English, such classifiers are usually absent ("four chairs") or optional ("two bottles of beer" or "two beers"), a classifier is almost always used in Thai (hence "chair four item" and "beer two bottle").

Pronouns

Subject pronouns are often omitted, with nicknames used where English would use a pronoun. See informal and formal names for more details. Pronouns, when used, are ranked in honorific registers, and may also make a T–V distinction in relation to kinship and social status. Specialised pronouns are used for those with royal and noble titles, and for clergy. The following are appropriate for conversational use:

| Word | RTGS | IPA | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ผม | phom | [pʰǒm] | I/me (masculine; formal) |

| ดิฉัน | dichan | [dìʔt͡ɕʰán]) | I/me (feminine; formal) |

| ฉัน | chan | [t͡ɕʰǎn] | I/me (mainly used by women; informal) Commonly pronounced as [t͡ɕʰán] |

| เรา | rao | [raw] | we/us, I/me (casual), you (sometimes used but only when older person speaks to younger person) |

| คุณ | khun | [kʰun] | you (polite) |

| ท่าน | than | [tʰân] | you (highly honorific) |

| เธอ | thoe | [tʰɤː] | you (informal), she/her (informal) |

| พี่ | phi | [pʰîː] | older brother, sister (also used for older acquaintances) |

| น้อง | nong | [nɔːŋ] | younger brother, sister (also used for younger acquaintances) |

| เขา | khao | [kʰǎw] | he/him, she/her |

| มัน | man | [man] | it, he/she (sometimes casual or offensive if used to refer to a person) |

The reflexive pronoun is ตัวเอง (tua eng), which can mean any of: myself, yourself, ourselves, himself, herself, themselves. This can be mixed with another pronoun to create an intensive pronoun, such as ตัวผมเอง (tua phom eng, lit: I myself) or ตัวคุณเอง (tua khun eng, lit: you yourself). Thai also does not have a separate possessive pronoun. Instead, possession is indicated by the particle ของ (khong). For example, "my mother" is แม่ของผม (mae khong phom, lit: mother of I). This particle is often implicit, so the phrase is shortened to แม่ผม (mae phom). Plural pronouns can be easily constructed by adding the word พวก (puak) in front of a singular pronoun as in พวกเขา (puak khao) meaning they or พวกเธอ (puak thoe) meaning the plural sense of you. The only exception to this is เรา (rao), which can be used as singular (informal) or plural, but can also be used in the form of พวกเรา (puak rao), which is only plural.

Thai has many more pronouns than those listed above. Their usage is full of nuances. For example:

- "ผม เรา ฉัน ดิฉัน หนู กู ข้า กระผม ข้าพเจ้า กระหม่อม อาตมา กัน ข้าน้อย ข้าพระพุทธเจ้า อั๊ว เขา" all translate to "I", but each expresses a different gender, age, politeness, status, or relationship between speaker and listener.

- เรา (rao) can be first person (I), second person (you), or both (we), depending on the context.

- Children or younger female could use or being referred by word หนู (nu) when talking with older person. The word หนู could be both feminine first person (I) and feminine second person (you) and also neuter first and neuter second person for children.

- หนู commonly means rat or mouse. It could refers to small creature in general

- The second person pronoun เธอ (thoe) (lit: you) is semi-feminine. It is used only when the speaker or the listener (or both) are female. Males usually don't address each other by this pronoun.

- Both คุณ (khun) and เธอ (thoe) are polite neuter second person pronouns. However, คุณเธอ (khun thoe) is a feminine derogative third person.

- Instead of a second person pronoun such as "คุณ" (you), it is much more common for unrelated strangers to call each other "พี่ น้อง ลุง ป้า น้า อา ตา ยาย" (brother/sister/aunt/uncle/granny).

- To express deference, the second person pronoun is sometimes replaced by a profession, similar to how, in English, presiding judges are always addressed as "your honor" rather than "you". In Thai, students always address their teachers by "ครู" or "คุณครู" or "อาจารย์" (each means "teacher") rather than คุณ (you). Teachers, monks, and doctors are almost always addressed this way.

Particles

The particles are often untranslatable words added to the end of a sentence to indicate respect, a request, encouragement or other moods (similar to the use of intonation in English), as well as varying the level of formality. They are not used in elegant (written) Thai. The most common particles indicating respect are ครับ (khrap, [kʰráp], with a high tone) when the speaker is male, and ค่ะ (kha, [kʰâ], with a falling tone) when the speaker is female; these can also be used to indicate an affirmative, though the ค่ะ (falling tone) is changed to a คะ (high tone).

Other common particles are:

| Word | RTGS | IPA | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| จ๊ะ | cha/ja | [t͡ɕáʔ] | indicating a request |

| จ้ะ, จ้า or จ๋า | cha/ja | [t͡ɕâː] | indicating emphasis |

| ละ or ล่ะ | la | [láʔ] | indicating emphasis |

| สิ | si | [sìʔ] | indicating emphasis or an imperative |

| นะ | na | [náʔ] | softening; indicating a request |

Register

As noted above, Thai has several registers, each having certain usages, such as colloquial, formal, literary, and poetic. Thus, the word "eat" can be กิน (kin; common), แดก (daek; vulgar), ยัด (yat; vulgar), บริโภค (boriphok; formal), รับประทาน (rapprathan; formal), ฉัน (chan; religious), or เสวย (sawoei; royal), as illustrated below:

| "to eat" | IPA | Usage | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| กิน | /kīn/ | common | |

| แดก | /dɛ̀ːk/ | vulgar | |

| ยัด | /ját/ | vulgar | Original meaning is 'to cram' |

| บริโภค | /bɔ̄ː.ri.pʰôːk/ | formal, literary | |

| รับประทาน | /ráp.pra.tʰāːn/ | formal, polite | Often shortened to ทาน /tʰāːn/. |

| ฉัน | /t͡ɕʰǎn/ | religious | |

| เสวย | /sa.wɤ̌ːj/ | royal |

Thailand also uses the distinctive Thai six-hour clock in addition to the 24-hour clock.

Vocabulary

Other than compound words and words of foreign origin, most words are monosyllabic.

Chinese-language influence was strong until the 13th century when the use of Chinese characters was abandoned, and replaced by Sanskrit and Pali scripts. However, the vocabulary of Thai retains many words borrowed from Middle Chinese.[17][18][19]

Later most vocabulary was borrowed from Sanskrit and Pāli; Buddhist terminology is particularly indebted to these. Indic words have a more formal register, and may be compared to Latin and French borrowings in English. Old Khmer has also contributed its share, especially in regard to royal court terminology. Since the beginning of the 20th century, however, the English language has had the greatest influence, especially for scientific, technical, international, and other modern terms. Many Teochew Chinese words are also used, some replacing existing Thai words (for example, the names of basic numbers; see also Sino-Xenic).[citation needed]

| Origin | Example | IPA | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Native Tai | ไฟ น้ำ เมือง รุ่งเรือง |

/fāj/ /náːm/ /mɯ̄əŋ/ /rûŋ.rɯ̄əŋ/ |

fire water city prosperous |

| Indic sources: Pali or Sanskrit |

อัคนี ชล นคร วิโรจน์ |

/ʔāk.kʰa.nīː/ /t͡ɕōn/ /náʔ.kʰɔ̄ːn/ /wíʔ.rôːt/ |

fire water city prosperous |

Arabic-origin

| Arabic words | Thai rendition | IPA | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| قُرْآن (Qurʾān) | อัลกุรอาน or โกหร่าน | /an.kù.rá.aːn/ or /kō.ràːn/ | means Quran |

| رجم (rajm) | ระยำ | /rá.jam/ | means bad, vile (pejorative) |

Chinese-origin

From Middle Chinese or Teochew Chinese.

| Chinese words | Thai rendition | IPA | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| 交椅 | เก้าอี้ | /kâw.ʔîː/ | chair |

| 粿條 / 粿条 | ก๋วยเตี๋ยว | /kǔəj.tǐəw/ | rice noodle |

| 姐 | เจ๊ | /t͡ɕéː/ | older sister (used in Chinese Thai community) |

| 二 | ยี่ | /jîː/ | two (archaic), but still used in words like twenty ยี่สิบ /jîː sìp/ |

| 豆 | ถั่ว | /tʰùə/ | bean |

| 盎 | อ่าง | /ʔàːŋ/ | basin |

| 膠 | กาว | /kāːw/ | glue |

| 鯁 | ก้าง | /kâːŋ/ | fishbone |

| 坎 | ขุม | /kʰǔm/ | pit |

| 塗 | ทา | /tʰāː/ | means to smear |

| 退 | ถอย | /tʰɔ̌j/ | to step back |

English-origin

| English words | Thai rendition | IPA | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| bank | แบงก์ | /bɛ́ːŋ/ | means bank or banknote |

| bill | บิล | /biw/ or /bin/ | |

| cake | เค้ก | /kʰéːk/ | |

| captain | กัปตัน | /kàp.tān/ | |

| cartoon | การ์ตูน | /kāː.tūːn/ | |

| clinic | คลินิก | /kʰlīː.nìk/ | |

| computer | คอมพิวเตอร์ | /kʰɔ̄m.pʰíw.tɤ̂ː/ | colloquially shortened to คอม /kʰɔ̄m/ |

| corruption | คอรัปชั่น | /kʰɔː.ráp.tɕʰân/ | |

| diesel | ดีเซล | /dīː.sēn/ | |

| dinosaur | ไดโนเสาร์ | /dāi.nōː.sǎu/ | |

| duel | ดวล | /dūən/ | |

| อีเมล | /ʔīː.mēːw/ | ||

| fashion | แฟชั่น | /fɛ̄ː.t͡ɕʰân/ | |

| golf | กอล์ฟ | /kɔ́ːp/ | |

| government | กัดฟันมัน | /kàt.fān.mān/ | (obsolete) |

| graph | กราฟ | /kráːp/ or /káːp/ | |

| plastic | พลาสติก | /pʰláːt.sà.tìk/ | (educated speech) |

| /pʰát.tìk/ | |||

| quota | โควตา | /kwōː.tâː/ | |

| shampoo | แชมพู | /t͡ɕʰɛ̄m.pʰūː/ | |

| suit | สูท | /sùːt/ | |

| suite | สวีท | /sà.wìːt/ | |

| taxi | แท็กซี่ | /tʰɛ́k.sîː/ | |

| technology | เทคโนโลยี | /tʰék.nōː.lōː.jîː/ | |

| titanium | ไทเทเนียม | /tʰāj.tʰēː.nîəm/ | |

| visa | วีซ่า | /wīː.sâː/ | |

| wreath | (พวง)หรีด | /rìːt/ |

French-origin

| French words | Thai rendition | IPA | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| aval | อาวัล | /ʔāː.wān/ | |

| buffet | บุฟเฟต์ | /búp.fêː/ | |

| café | คาเฟ่ | /kāː.fɛ̄ː/ | |

| chauffeur | โชเฟอร์ | /t͡ɕʰōː.f`ɤː/ | |

| consul | กงสุล | /kōŋ.sǔn/ | |

| coupon | คูปอง | /kʰūː.pɔ̄ŋ/ | |

| pain | (ขนม)ปัง | /pāŋ/ | |

| parquet | ปาร์เกต์ | /pāː.kêː/ | |

| pétanque | เปตอง | /pēː.tɔ̄ŋ/ |

Khmer-origin

From Old Khmer.

| Khmer words | Thai rendition | IPA | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| ក្រុង (grong) | กรุง | /krūŋ/ | means city, as in Bangkok กรุงเทพฯ /krūŋ tʰêːp/ |

| ខ្ទើយ (ktəəy) | กะเทย | /kà.tɤ̄ːj/ | means Kathoey |

| ច្រមុះ (chrâmuh) | จมูก | /t͡ɕà.mùːk/ | means nose |

| ច្រើន (craən) | เจริญ | /t͡ɕà.rɤ̄ːn/ | means prosperous |

| ឆ្លាត/ឆ្លាស (chlāt) | ฉลาด | /t͡ɕʰà.làːt/ | means smart |

| ថ្នល់ (thnâl) | ถนน | /tʰà.nǒn/ | means road |

| ភ្លើង (/pləəŋ/) | เพลิง | /pʰlɤ̄ːŋ/ | means fire |

| ទន្លេ (tonle) | ทะเล | /tʰá.lēː/ | means sea |

Portuguese-origin

The Portuguese were the first Western-nation to arrive in what is modern-day Thailand in the 16th century during the Ayutthaya period. Its influence in trade, especially weaponry, allowed them to establish a community just outside the capital and practice their faith, as well as exposing and converting the locals to Christianity. Thus, Portuguese words involving trade and religion were introduced and used by the locals.

| Portuguese words | Thai rendition | IPA | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|

| carta / cartaz | กระดาษ | /krà.dàːt/ | means paper |

| garça | (นก)กระสา | /krà.sǎː/ | means heron |

| leilão | เลหลัง | /lēː.lǎŋ/ | means auction or low-priced |

| padre | บาท(หลวง) | /bàːt.lǔaŋ/ | means (Christian) priest[20] |

| real | เหรียญ | /rǐan/ | means coin |

| sabão | สบู่ | /sà.bùː/ | means soap |

History

Thai has undergone various historical sound changes. Some of the most significant changes, at least in terms of consonants and tones, occurred between Old Thai spoken when the language was first written and Thai of present, reflected in the orthography.

Old Thai

Old Thai had a three-way tone distinction on live syllables (those not ending in a stop), with no possible distinction on dead syllables (those ending in a stop, i.e. either /p/, /t/, /k/ or the glottal stop which automatically closes syllables otherwise ending in a short vowel).

There was a two-way voiced vs. voiceless distinction among all fricative and sonorant consonants, and up to a four-way distinction among stops and affricates. The maximal four-way occurred in labials (/p pʰ b ʔb/) and dentals (/t tʰ d ʔd/); the three-way distinction among velars (/k kʰ ɡ/) and palatals (/tɕ tɕʰ dʑ/), with the glottalized member of each set apparently missing.

The major change between old and modern Thai was due to voicing distinction losses and the concomitant tone split. This may have happened between about 1300 and 1600 CE, possibly occurring at different times in different parts of the Thai-speaking area. All voiced–voiceless pairs of consonants lost the voicing distinction:

- Plain voiced stops (/b d ɡ dʑ/) became voiceless aspirated stops (/pʰ tʰ kʰ tɕʰ/).[f]

- Voiced fricatives became voiceless.

- Voiceless sonorants became voiced.

However, in the process of these mergers the former distinction of voice was transferred into a new set of tonal distinctions. In essence, every tone in Old Thai split into two new tones, with a lower-pitched tone corresponding to a syllable that formerly began with a voiced consonant, and a higher-pitched tone corresponding to a syllable that formerly began with a voiceless consonant (including glottalized stops). An additional complication is that formerly voiceless unaspirated stops/affricates (original /p t k tɕ ʔb ʔd/) also caused original tone 1 to lower, but had no such effect on original tones 2 or 3.

The above consonant mergers and tone splits account for the complex relationship between spelling and sound in modern Thai. Modern "low"-class consonants were voiced in Old Thai, and the terminology "low" reflects the lower tone variants that resulted. Modern "mid"-class consonants were voiceless unaspirated stops or affricates in Old Thai—precisely the class that triggered lowering in original tone 1 but not tones 2 or 3. Modern "high"-class consonants were the remaining voiceless consonants in Old Thai (voiceless fricatives, voiceless sonorants, voiceless aspirated stops). The three most common tone "marks" (the lack of any tone mark, as well as the two marks termed mai ek and mai tho) represent the three tones of Old Thai, and the complex relationship between tone mark and actual tone is due to the various tonal changes since then. Note also that since the tone split, the tones have changed in actual representation to the point that the former relationship between lower and higher tonal variants has been completely obscured. Furthermore, the six tones that resulted after the three tones of Old Thai were split have since merged into five in standard Thai, with the lower variant of former tone 2 merging with the higher variant of former tone 3, becoming the modern "falling" tone.[g]

Early Old Thai also apparently had velar fricatives /x ɣ/ as distinct phonemes. These were represented by the now-obsolete letters ฃ kho khuat and ฅ kho khon, respectively. During the Old Thai period, these sounds merged into the corresponding stops /kʰ ɡ/, and as a result the use of these letters became unstable.

At some point in the history of Thai, a palatal nasal phoneme /ɲ/ also existed, inherited from Proto-Tai. A letter ญ yo ying also exists, which is used to represent a palatal nasal in words borrowed from Sanskrit and Pali, and is currently pronounced /j/ at the beginning of a syllable but /n/ at the end of a syllable. Most native Thai words that are reconstructed as beginning with /ɲ/ are also pronounced /j/ in modern Thai, but generally spelled with ย yo yak, which consistently represents /j/. This suggests that /ɲ/ > /j/ in native words occurred in the pre-literary period. It is unclear whether Sanskrit and Pali words beginning with /ɲ/ were borrowed directly with a /j/, or whether a /ɲ/ was re-introduced, followed by a second change /ɲ/ > /j/.

Proto-Tai also had a glottalized palatal sound, reconstructed as /ʔj/ in Li Fang-Kuei (1977[full citation needed]). Corresponding Thai words are generally spelled หย, which implies an Old Thai pronunciation of /hj/ (or /j̊/), but a few such words are spelled อย, which implies a pronunciation of /ʔj/ and suggests that the glottalization may have persisted through to the early literary period.

Vowel developments

The vowel system of modern Thai contains nine pure vowels and three centering diphthongs, each of which can occur short or long. According to Li (1977[full citation needed]), however, many Thai dialects have only one such short–long pair (/a aː/), and in general it is difficult or impossible to find minimal short–long pairs in Thai that involve vowels other than /a/ and where both members have frequent correspondences throughout the Tai languages. More specifically, he notes the following facts about Thai:

- In open syllables, only long vowels occur. (This assumes that all apparent cases of short open syllables are better described as ending in a glottal stop. This makes sense from the lack of tonal distinctions in such syllables, and the glottal stop is also reconstructible across the Tai languages.)

- In closed syllables, the long high vowels /iː ɯː uː/ are rare, and cases that do exist typically have diphthongs in other Tai languages.

- In closed syllables, both short and long mid /e eː o oː/ and low /ɛ ɛː ɔ ɔː/ do occur. However, generally, only words with short /e o/ and long /ɛː ɔː/ are reconstructible back to Proto-Tai.

- Both of the mid back unrounded vowels /ɤ ɤː/ are rare, and words with such sounds generally cannot be reconstructed back to Proto-Tai.

Furthermore, the vowel that corresponds to short Thai /a/ has a different and often higher quality in many of the Tai languages compared with the vowel corresponding to Thai /aː/.

This leads Li to posit the following:

- Proto-Tai had a system of nine pure vowels with no length distinction, and possessing approximately the same qualities as in modern Thai: high /i ɯ u/, mid /e ɤ o/, low /ɛ a ɔ/.

- All Proto-Tai vowels were lengthened in open syllables, and low vowels were also lengthened in closed syllables.

- Modern Thai largely preserved the original lengths and qualities, but lowered /ɤ/ to /a/, which became short /a/ in closed syllables and created a phonemic length distinction /a aː/. Eventually, length in all other vowels became phonemic as well and a new /ɤ/ (both short and long) was introduced, through a combination of borrowing and sound change. Li believes that the development of long /iː ɯː uː/ from diphthongs, and the lowering of /ɤ/ to /a/ to create a length distinction /a aː/, had occurred by the time of Proto-Southwestern-Tai, but the other missing modern Thai vowels had not yet developed.

Note that not all researchers agree with Li. Pittayaporn (2009[full citation needed]), for example, reconstructs a similar system for Proto-Southwestern-Tai, but believes that there was also a mid back unrounded vowel /ə/ (which he describes as /ɤ/), occurring only before final velar /k ŋ/. He also seems to believe that the Proto-Southwestern-Tai vowel length distinctions can be reconstructed back to similar distinctions in Proto-Tai.

Connection to ancient Yue language(s)

Thai descends from proto-Tai-Kadai, which has been hypothesized to originate in the Lower Yangtze valleys. Ancient Chinese texts refer to non-Sinitic languages spoken cross this substantial region and their speakers as "Yue". Although those languages are extinct, traces of their existence could be found in unearthed inscriptional materials, ancient Chinese historical texts and non-Han substrata in various Southern Chinese dialects. Thai, as the most-spoken language in Tai-Kadai language family, has been used extensively in historical-comparative linguistics to identify the origins of language(s) spoken in the ancient region of South China. One of the very few direct records of non-Sinitic speech in pre-Qin and Han times having been preserved so far is the "Song of the Yue Boatman" (Yueren Ge 越人歌), which was transcribed phonetically in Chinese characters in 528 BC, and found in the 善说 Shanshuo chapter of the Shuoyuan 说苑 or 'Garden of Persuasions'. In the early 80's the Zhuang linguist Wei Qingwen using reconstructed Old Chinese for the characters discovered that the resulting vocabulary showed strong resemblance to modern Zhuang.[21] Later, Zhengzhang Shangfang (1991) followed Wei's insight but used Thai script for comparison, since this orthography dates from the 13th century and preserves archaisms vis-à-vis the modern pronunciation.[22] The following is a simplified interpretation of the "Song of the Yue Boatman" by Zhengzhang Shangfang quoted by David Holm (2013) with Thai script and Chinese glosses being omitted:[23][h]

| 濫 | 兮 | 抃 | 草 | 濫 | ||||||||||||

| ɦgraams | ɦee | brons | tshuuʔ | ɦgraams | ||||||||||||

| glamx | ɦee | blɤɤn | cɤɤ, cɤʔ | glamx | ||||||||||||

| evening | ptl. | joyful | to meet | evening | ||||||||||||

| Oh, the fine night, we meet in happiness tonight! | ||||||||||||||||

| 予 | 昌 | 枑 | 澤 | 予 | 昌 | 州 | ||||||||||

| la | thjang < khljang | gaah | draag | la | thjang | tju < klju | ||||||||||

| raa | djaangh | kraʔ - | ʔdaak | raa | djaangh | cɛɛu | ||||||||||

| we, I | be apt to | shy, ashamed | we, I | be good at | to row | |||||||||||

| I am so shy, ah! I am good at rowing. | ||||||||||||||||

| 州 | 𩜱 | 州 | 焉 | 乎 | 秦 | 胥 胥 | ||||||||||

| tju | khaamʔ | tju | jen | ɦaa | dzin | sa | ||||||||||

| cɛɛu | khaamx | cɛɛu | jɤɤnh | ɦaa | djɯɯnh | saʔ | ||||||||||

| to row | to cross | to row | slowly | ptl. | joyful | satisfy, please | ||||||||||

| Rowing slowly across the river, ah! I am so pleased! | ||||||||||||||||

| 縵 | 予 | 乎 | 昭 | 澶 | 秦 | 踰 | ||||||||||

| moons | la | ɦaa | tjau < kljau | daans | dzin | lo | ||||||||||

| mɔɔm | raa | ɦaa | caux | daanh | djin | ruux | ||||||||||

| dirty, ragged | we, I | ptl. | prince | Your Excellency | acquainted | know | ||||||||||

| Dirty though I am, ah! I made acquaintance with your highness the Prince. | ||||||||||||||||

| 滲 | 惿 | 隨 | 河 | 湖 | ||||||||||||

| srɯms | djeʔ < gljeʔ | sɦloi | gaai | gaa | ||||||||||||

| zumh | caï | rɯaih | graih | gaʔ | ||||||||||||

| to hide | heart | forever, constantly | to yearn | ptl. | ||||||||||||

| Hidden forever in my heart, ah! is my adoration and longing. | ||||||||||||||||

Besides this classical case, various papers in historical linguistics have employed Thai for comparative purposes in studying the linguistic landscape of the ancient region of Southern China. Proto-reconstructions of some scattered non-Sinitic words found in the two ancient Chinese fictional texts, Mu tianzi zhuan 穆天子傳 (4th c. B.C.) and Yuejue shu 越絕書 (1st c. A.D.), are used to compare to Thai/Siamese and its related languages in Tai-Kadai language family in an attempt to identify the origins of those words. The following examples are cited from Wolfgang Behr's work (2002):

- "吳謂善「伊」, 謂稻道「缓」, 號從中國, 名從主人。"[24]

"The Wú say yī for 'good' and huăn for 'way', i.e. in their titles they follow the central kingdoms, but in their names they follow their own lords."

伊 yī < MC ʔjij < OC *bq(l)ij ← Siamese diiA1, Longzhou dai1, Bo'ai nii1 Daiya li1, Sipsongpanna di1, Dehong li6 < proto-Tai *ʔdɛiA1 | Sui ʔdaai1, Kam laai1, Maonan ʔdaai1, Mak ʔdaai6 < proto-Kam-Sui/proto-Kam-Tai *ʔdaai1 'good'

缓 [huăn] < MC hwanX < OC *awan ← Siamese honA1, Bo'ai hɔn1, Dioi thon1 < proto-Tai *xronA1| Sui khwən1-i, Kam khwən1, Maonan khun1-i, Mulam khwən1-i < proto-Kam-Sui *khwən1 'road, way' | proto-Hlai *kuun1 || proto-Austronesian *Zalan (Thurgood 1994:353)

絕 jué < MC dzjwet < OC *bdzot ← Siamese codD1 'to record, mark' (Zhengzhang Shangfang 1999:8)

- "姑中山者越銅官之山也, 越人謂之銅, 「姑[沽]瀆」。"[25]

"The Middle mountains of Gū are the mountains of the Yuè's bronze office, the Yuè people call them 'Bronze gū[gū]dú'."

「姑[沽]瀆」 gūdú < MC ku=duwk < OC *aka=alok

← Siamese kʰauA1 'horn', Daiya xau5, Sipsongpanna xau1, Dehong xau1, Lü xău1, Dioi kaou1 'mountain, hill' < proto-Tai *kʰauA2; Siamese luukD2l 'classifier for mountains', Siamese kʰauA1-luukD2l 'mountain' || cf. OC 谷 gǔ < kuwk << *ak-lok/luwk < *akə-lok/yowk < *blok 'valley'

- "越人謂船爲「須盧」。"[26]

"... The Yuè people call a boat xūlú. ('beard' & 'cottage')"

? ← Siamese saʔ 'noun prefix'

← Siamese rɯaA2, Longzhou lɯɯ2, Bo'ai luu2, Daiya hə2, Dehong hə2 'boat' < proto-Tai *drɯ[a,o] | Sui lwa1/ʔda1, Kam lo1/lwa1, Be zoa < proto-Kam-Sui *s-lwa(n)A1 'boat'

- "[劉]賈築吳市西城, 名曰「定錯」城。"[27]

"[Líu] Jiă (the king of Jīng 荆) built the western wall, it was called dìngcuò ['settle(d)' & 'grindstone'] wall."

定 dìng < MC dengH < OC *adeng-s

← Siamese diaaŋA1, Daiya tʂhəŋ2, Sipsongpanna tseŋ2 'wall'

? ← Siamese tokD1s 'to set→sunset→west' (tawan-tok 'sun-set' = 'west'); Longzhou tuk7, Bo'ai tɔk7, Daiya tok7, Sipsongpanna tok7 < proto-Tai *tokD1s ǀ Sui tok7, Mak tok7, Maonan tɔk < proto-Kam-Sui *tɔkD1

See also

Notes

- ^ In Thai: Template:Wiktth Phasa Thai [pʰāːsǎː tʰāj]

- ^ Although "Thai" and "Central Thai" has become more common, the older term "Siamese" is still used by linguists, especially to distinguish it from other Tai languages (Diller 2008:6[full citation needed]). "Proto-Thai", for example, is the ancestor of all of Southwestern Tai, not just of Siamese (Rischel 1998[full citation needed]).

- ^ Occasionally referred to as the "Central Thai people" in linguistics and anthropology to avoid confusion.

- ^ The Royal Society of Thailand promotes this dialect as Krungthep Thai (ภาษาไทยถิ่นกรุงเทพ) or as "Bangkok dialect", however the locals do not consider the language they speak as such. Linguists refer to Bangkok Thai as "Thonburi-side dialect", which was originally spoken by Persians origin and the residents of Portuguese origin. The name of Krungthep refers to Phra-Nakhon side, which is spoken mainly by Sino-Siamese and Mon-Siamese residents; the Royal Society classified it as Chinese accent. The Outer Bangkok dialect is a more lenient concept to linguists, and is usually referred to as Ayutthayan dialect, for being a standard dialect spoken by Siamese and Siamese of ethnic Mon, which originated in Ayutthaya Province and Pathum Thani Province

- ^ These dialect oftentimes viewed as Krung Thep dialect by outsider.

- ^ The glottalized stops /ʔb ʔd/ were unaffected, as they were treated in every respect like voiceless unaspirated stops due to the initial glottal stop. These stops are often described in the modern language as phonemically plain stops /b d/, but the glottalization is still commonly heard.

- ^ Modern Lao and northern Thai dialects are often described as having six tones, but these are not necessarily due to preservation of the original six tones resulting from the tone split. For example, in standard Lao, both the high and low variants of Old Thai tone 2 merged; however, the mid-class variant of tone 1 became pronounced differently from either the high-class or low-class variants, and all three eventually became phonemic due to further changes, e.g. /kr/ > /kʰ/. For similar reasons, Lao has developed more than two tonal distinctions in "dead" syllables.

- ^ The upper row represents the original text, the next row the Old Chinese pronunciation, the third a transcription of written Thai, and the fourth line English glosses. Finally, there is Zhengzhang's English translation.

References

- ^ a b Thai at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ "Languages of ASEAN". Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Not to be confused with Central Tai

- ^ "Ausbau and Abstand languages". Ccat.sas.upenn.edu. 1995-01-20. Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ^ Peansiri Vongvipanond (Summer 1994). "Linguistic Perspectives of Thai Culture". paper presented to a workshop of teachers of social science. University of New Orleans. p. 2. Retrieved 26 April 2011.

The dialect one hears on radio and television is the Bangkok dialect, considered the standard dialect.

- ^ Template:Cite article

- ^ Andrew Simpson (2007). Language and national identity in Asia. Oxford University Press.

Standard Thai is a form of Central Thai based on the variety of Thai spoken earlier by the elite of the court, and now by the educated middle and upper classes of Bangkok. It ... was standardized in grammar books in the nineteenth century, and spread dramatically from the 1930s onwards, when public education became much more widespread

- ^ Antonio L. Rappa; Lionel Wee (2006), Language Policy and Modernity in Southeast Asia: Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, Springer, pp. 114–115

- ^ "The Languages spoken in Thailand". Studycountry. Retrieved 2017-12-26.

- ^ Royal Thai General System of Transcription, published by the Thai Royal Institute only in Thai

- ^ Handbook and standard for traffic signs (PDF) (in Thai), Appendix ง

- ^ ISO Standard.

- ^ Tingsabadh & Abramson (1993:25)

- ^ Frankfurter, Oscar. Elements of Siamese grammar with appendices. American Presbyterian mission press, 1900 [1] (Full text available on Google Books)

- ^ Teeranon, Phanintra. (2007). "The change of Standard Thai high tone: An acoustic study and a perceptual experiment". SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics, 4(3), 1-16.

- ^ Thepboriruk, Kanjana. (2010). "Bangkok Thai Tones Revisited". Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society, 3(1), 86-105.

- ^ Martin Haspelmath, Uri Tadmor Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook 2009 -- Page 611 "Thai is of special interest to lexical borrowing for various reasons. The copious borrowing of basic vocabulary from Middle Chinese and later from Khmer indicates that, given the right sociolinguistic context, such vocabulary is not at all immune ..."

- ^ Harald Haarmann Language in Ethnicity: A View of Basic Ecological Relations 1986- Page 165 "In Thailand, for instance, where the Chinese influence was strong until the Middle Ages, Chinese characters were abandoned in written Thai in the course of the thirteenth century."

- ^ Paul A. Leppert Doing Business With Thailand -1992 Page 13 "At an early time the Thais used Chinese characters. But, under the influence of Indian traders and monks, they soon dropped Chinese characters in favor of Sanskrit and Pali scripts."

- ^ สยาม-โปรตุเกสศึกษา: คำเรียก "ชา กาแฟ" ใครลอกใคร ไทย หรือ โปรตุเกส

- ^ Edmondson 2007, p. 16.

- ^ Zhengzhang 1991, pp. 159–168.

- ^ Holm 2013, pp. 784–785.

- ^ Behr 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b Behr 2002, p. 2.

- ^ Behr 2002, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Behr 2002, p. 3.

Sources

- อภิลักษณ์ ธรรมทวีธิกุล และ กัลยารัตน์ ฐิติกานต์นารา. 2549."การเน้นพยางค์กับทำนองเสียงภาษาไทย" (Stress and Intonation in Thai ) วารสารภาษาและภาษาศาสตร์ ปีที่ 24 ฉบับที่ 2 (มกราคม – มิถุนายน 2549) หน้า 59-76

- สัทวิทยา : การวิเคราะห์ระบบเสียงในภาษา. 2547. กรุงเทพฯ : สำนักพิมพ์มหาวิทยาลัยเกษตรศาสตร์

- Diller, Anthony van Nostrand. 2008. The Tai–Kadai Languages.

- Gandour, Jack, Tumtavitikul, Apiluck and Satthamnuwong, Nakarin. 1999. "Effects of Speaking Rate on the Thai Tones." Phonetica 56, pp. 123–134.

- Li, Fang-Kuei. A handbook of comparative Tai. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1977. Print.

- Rischel, Jørgen. 1998. 'Structural and Functional Aspects of Tone Split in Thai'. In Sound structure in language, 2009.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck, 1998. "The Metrical Structure of Thai in a Non-Linear Perspective". Papers presented to the Fourth Annual Meeting of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 1994, pp. 53–71. Udom Warotamasikkhadit and Thanyarat Panakul, eds. Temple, Arizona: Program for Southeast Asian Studies, Arizona State University.

- Apiluck Tumtavitikul. 1997. "The Reflection on the X′ category in Thai". Mon–Khmer Studies XXVII, pp. 307–316.

- อภิลักษณ์ ธรรมทวีธิกุล. 2539. "ข้อคิดเกี่ยวกับหน่วยวากยสัมพันธ์ในภาษาไทย" วารสารมนุษยศาสตร์วิชาการ. 4.57-66.

- Tumtavitikul, Appi. 1995. "Tonal Movements in Thai". The Proceedings of the XIIIth International Congress of Phonetic Sciences, Vol. I, pp. 188–121. Stockholm: Royal Institute of Technology and Stockholm University.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck. 1994. "Thai Contour Tones". Current Issues in Sino-Tibetan Linguistics, pp. 869–875. Hajime Kitamura et al., eds, Ozaka: The Organization Committee of the 26th Sino-Tibetan Languages and Linguistics, National Museum of Ethnology.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck. 1993. "FO – Induced VOT Variants in Thai". Journal of Languages and Linguistics, 12.1.34 – 56.

- Tumtavitikul, Apiluck. 1993. "Perhaps, the Tones are in the Consonants?" Mon–Khmer Studies XXIII, pp. 11–41.

- Higbie, James and Thinsan, Snea. Thai Reference Grammar: The Structure of Spoken Thai. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2003. ISBN 974-8304-96-5.

- Nacaskul, Karnchana, Ph.D. (ศาสตราจารย์กิตติคุณ ดร.กาญจนา นาคสกุล) Thai Phonology, 4th printing. (ระบบเสียงภาษาไทย, พิมพ์ครั้งที่ 4) Bangkok: Chulalongkorn Press, 1998. ISBN 978-974-639-375-1.

- Nanthana Ronnakiat, Ph.D. (ดร.นันทนา รณเกียรติ) Phonetics in Principle and Practical. (สัทศาสตร์ภาคทฤษฎีและภาคปฏิบัติ) Bangkok: Thammasat University, 2005. ISBN 974-571-929-3.

- Segaller, Denis. Thai Without Tears: A Guide to Simple Thai Speaking. Bangkok: BMD Book Mags, 1999. ISBN 974-87115-2-8.

- Smyth, David (2002). Thai: An Essential Grammar, first edition. London: Routledge.

- Smyth, David (2014). Thai: An Essential Grammar, second edition. London: Routledge.

- Tingsabadh, M.R. Kalaya; Abramson, Arthur (1993), "Thai", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 23 (1): 24–28, doi:10.1017/S0025100300004746

{{citation}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Behr, Wolfgang (2002). "Stray loanword gleanings from two Ancient Chinese fictional texts". 16e Journées de Linguistique d'Asie Orientale, Centre de Recherches Linguistiques sur l'Asie Orientale (E.H.E.S.S.), Paris: 1–6.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Edmondson, Jerold A. (2007). "The power of language over the past: Tai settlement and Tai linguistics in southern China and northern Vietnam" (PDF). Studies in Southeast Asian Languages and Linguistics, Jimmy G. Harris, Somsonge Burusphat and James E. Harris, Ed. Bangkok, Thailand: Ek Phim Thai Co. LTD.: 1–25.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Holm, David (2013). Mapping the Old Zhuang Character Script: A Vernacular Writing System from Southern China. BRILL. ISBN 978-9-004-22369-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Zhengzhang, Shangfang (1991). "Decipherment of Yue-Ren-Ge (Song of the Yue boatman)". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 20 (2): 159–168. doi:10.3406/clao.1991.1345.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Further reading

- Inglis, Douglas. 1999. Lexical conceptual structure of numeral classifiers in Thai-Part 1. Payap Research and Development Institute and The Summer Institute of Linguistics. Payap University.

- Inglis, Douglas. 2000. Grammatical conceptual structure of numeral classifiers in Thai-Part 2. Payap Research and Development Institute and The Summer Institute of Linguistics. Payap University.

- Inglis, Douglas. 2003. Conceptual structure of numeral classifiers in Thai. In Eugene E. Casad and Gary B. Palmer (eds.). Cognitive linguistics and non-Indo-European languages. CLR Series 18. nd Gary B. Palmer. Mouton deGruyter. 223-246.

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (June 2015) |

- IPA and SAMPA for Thai

- Structure of Thai Language (TH101) PDF version of university text book

- Consonant Ear Training Tape

- Tones of Tai Dialect

Glossaries and word lists

- Thai phrasebook from Wikivoyage

- Thai Swadesh list of basic vocabulary words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

Dictionaries

- English–Thai Dictionary: English–Thai bilingual online dictionary

- The Royal Institute Dictionary, official standard Thai–Thai dictionary

- Longdo Thai Dictionary LongdoDict

- Thai-English dictionary

- Thai2english.com: LEXiTRON-based Thai–English dictionary

- Daoulagad Thai: mobile OCR Thai–English dictionary

- Thai dictionaries for Stardict/GoldenDict - Thai - English (French, German, Russian and others) dictionaries in Stardict and GoldenDict formats

- Volubilis Dictionary VOLUBILIS (Romanized Thai - Thai - English - French) : free databases (ods/xlsx) and dictionaries (PDF) - Thai transcription system.

Learners' resources

- ThaiLearner ★★★★★ Free Android software to learn Thai language

- thai-language.com English speakers' online resource for the Thai language

- Say Hello in the Thai Language

- FSI Thai language course (Formerly at thailanguagewiki.com)

- Spoken Thai (30 exercises with audio)

- Thai books+Audio, a lot of books in Thai with audio.

Thai Keyboard

- Thai Keyboard Virtual Thai Keyboard