Muni Metro

| Muni Metro | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Inbound T Third train at Castro station | |||

Inbound L Taraval train on a street running track section negotiating San Francisco's hills | |||

| Overview | |||

| Owner | San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency | ||

| Locale | San Francisco, California | ||

| Transit type | Light rail/Streetcar | ||

| Number of lines | 6 (plus 1 peak-hour shuttle line) | ||

| Number of stations | 33 (9 subway, 24 surface)[1] 87 additional surface stops | ||

| Daily ridership | 162,500 (average weekday, Q4 2017)[2] | ||

| Annual ridership | 51.5 million (2017)[2] | ||

| Website | SFMTA | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | February 18, 1980 | ||

| Operator(s) | San Francisco Municipal Railway | ||

| Number of vehicles | 151 Breda light rail vehicles (high floor) 68 Siemens light rail vehicles on order (high floor)[3] | ||

| Train length | 75–225 feet (22.9–68.6 m) (1–3 LRVs)[4][5] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 36.8 mi (59.2 km)[6] | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge[4] | ||

| Electrification | Overhead lines, 600 V DC[4] | ||

| Average speed | 9.6 mph (15.4 km/h)[7] | ||

| Top speed | 50 mph (80 km/h)[8] | ||

| |||

The Muni Metro is a light rail system serving San Francisco, California, United States, operated by the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni), a division of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). With an average weekday ridership of 157,700 passengers as of the fourth quarter of 2019, Muni Metro is the United States' second busiest light rail system.[2] Muni Metro operates a fleet of 151 Breda light rail vehicles (LRVs), which are being supplemented and replaced by Siemens S200 SF LRVs.

Muni Metro is the modern incarnation of the traditional streetcar system that had served San Francisco since the late 19th century. While many streetcar lines in other cities, and even in San Francisco itself, were converted to buses after World War II, five lines survived until the early 1980s, when they were rerouted into the newly built Market Street subway. The system today traverses a number of different types of rights of way, including tunnels, reserved surface trackage with at-grade street crossings, and streetcar sections operating in mixed traffic; surface stops range from high-platform stations to traditional curbside streetcar stops. Recently, the system has undergone expansion, most notably the Third Street Light Rail Project, completed in 2007, which started the first new rail line in San Francisco in over half a century. Other projects, such as the Central Subway, are underway.

History

Beginnings

PCC entering the (now demolished) eastern portal of the Twin Peaks Tunnel – the original Muni subway segment. Photo taken February 1967.

PCC entering the (now demolished) eastern portal of the Twin Peaks Tunnel – the original Muni subway segment. Photo taken February 1967.The first street railroad in San Francisco was the San Francisco Market Street Railroad Company, which was incorporated in 1857 and began operating in 1860, with track along Market Street from California to Mission Dolores.[9] Muni Metro descended from the municipally-owned traditional streetcar system started on December 28, 1912, when the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) was established.[10] The first streetcar line, the A Geary, ran from Kearny and Market Streets in the Financial District to Fulton Street and 10th Avenue in the Richmond District.[11][12] The system slowly expanded, opening the Twin Peaks Tunnel in 1917,[13] allowing streetcars to run to the southwestern quadrant of the city. By 1921, the city was operating 304 miles (489 km) of electric trolley lines and 25 miles (40 km) of cable car lines.[14] The last line to start service before 2007 was the N Judah, which started service after the Sunset Tunnel opened in 1928.[15]

In the 1940s and 1950s, as in many North American cities, public transit in San Francisco was consolidated under the aegis of a single municipal corporation, which then began phasing out much of the streetcar network in favor of buses.[16] However, five heavily used streetcar lines traveled for at least part of their routes through tunnels or otherwise reserved right-of-way, and thus could not be converted to bus lines.[17] As a result, these lines, running PCC streetcars, continued in operation.

Market Street subway

Original plans for the BART system drawn up in the 1950s envisioned a double-decked subway tunnel under Market Street (known as the Market Street subway) in downtown San Francisco; the lower deck would be dedicated to express trains, while the upper would be served by local trains whose routes would spread south and west through the city. However, by 1961 these plans were altered; only a single BART route would travel through the city on the lower deck, while the upper deck would be served by the existing Muni streetcar routes.[18] The new tunnel would be connected to the existing Twin Peaks Tunnel. The new underground stations would feature high platforms, and the older stations would be retrofitted with the same, which meant that the PCCs could not be used in them. Hence, a fleet of new light rail vehicles was ordered from Boeing-Vertol, but were not delivered until 1979–80, even though the tunnel was completed in 1978. The K and M lines were extended to Balboa Park during this time, providing further connections to BART. (The J line also saw an extension there in 1991, which provided yet another BART connection at Glen Park.)

Boeing USSLRV passes an

Boeing USSLRV passes an  PCC at West Portal in November 1980.

PCC at West Portal in November 1980.On February 18, 1980, the Muni Metro was officially inaugurated, with weekday N line service in the subway.[19] The Metro service was implemented in phases, and the subway was served only on weekdays until 1982. The K Ingleside line began using the Metro subway on weekdays on June 11, 1980, the L Taraval and M Ocean View lines on December 17, 1980, and lastly the J Church line on June 17, 1981.[20] Meanwhile, weekend service on all five lines (J, K, L, M, N) continued to use PCC cars operating on the surface of Market Street through to the Transbay Terminal, and the Muni Metro was closed on weekends. At the end of the service day September 19, 1982, streetcar operations on the surface of Market Street were discontinued entirely, the remaining PCC cars taken out of service, and weekend service on the five light rail lines was temporarily converted to buses.[21][22] Finally, on November 20, 1982, the Muni Metro subway began operating seven days a week.[22]

At the time, there were no firm plans to revive any service on the surface of Market Street or return PCCs to regular running.[21] However, tracks were rehabilitated for the 1983 Historic Trolley Festival,[22] and the inauguration of the F line, served by heritage streetcars, followed in 1995.

By the late 1980s, Muni scheduled 20 trains per hour (TPH) through the Market Street subway at peak periods, with all trains using the crossover west of Embarcadero station to reverse direction.. To allow for high frequencies on the surface branches, eastbound trains were combined at West Portal and Duboce Portal, and westbound trains split at those locations. Two-car N Judah trains and one-car J Church trains (each 10TPH) combined at the Duboce Portal, while two-car L Taraval trains (10TPH) alternately combined with two-car M Ocean View and K Ingleside (each 5 TPH) trains at West Portal to form four-car trains. However, this provided suboptimal service; many inbound trains did not arrive at the portals in time to combine into longer trains.[23]

Muni meltdown

In the mid- to late-1990s, San Francisco grew more prosperous and its population expanded with the advent of the dot-com boom, and the Metro system began to feel the strain of increased commuter demand. Muni criticism had been something of a feature of life in San Francisco, and not without reason. The Boeing trains were sub-par and grew crowded quickly.[24] And the difficulty in running a hybrid streetcar and light rail system, with five lines merging into one, led to scheduling problems on the main trunk lines with long waits between arrivals and commuter-packed trains sometimes sitting motionless in tunnels for extended periods of time.[24]

Muni did take steps to address these problems. Newer, larger Breda cars were ordered, an extension of the system towards South Beach — where many of the new dot-coms were headquartered — was built, and the underground section was switched to Automatic Train Operation (ATO). The Breda cars, however, came in noisy, overweight, oversized, under-braked, and over-budget (their price grew from US$2.2 million per car to nearly US$3 million over the course of their production).[25][26] In fact, the new trains were so heavy (10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) more than the Boeing LRVs they replaced) that some homeowners, claiming that the exceptional weight of the Breda cars damaged their foundations, sued the city of San Francisco.[27] The Breda cars are longer and wider than the previous Boeing cars, necessitating the modification of subway stations and maintenance yards, as well as the rear view mirrors on the trains themselves.[26] Furthermore, the Breda cars do not run in three car trains, like the Boeing cars used to, as doing so had, in some instances, physically damaged the overhead power wires.[28] The Breda trains were so noisy that San Francisco budgeted over $15 million to quiet them down, while estimates range up to $1 million per car to remedy the excessive noise.[29] To this day, the Breda cars are noisier than the PCC or Boeing cars. In 1998, NTSB inspectors mandated a lower speed limit of 30 mph (48 km/h), down from 50 mph (80 km/h), because the brakes were problematic.[30][31]

The ATC system was plagued by numerous glitches when first implemented, initially causing significantly more harm than good. Common occurrences included sending trains down the wrong tracks, and, more often, inappropriately applying emergency braking.[32] Eventually the result was a spectacular service crisis, widely referred to as the "Muni meltdown", in the summer of 1998. During this period, two reporters for the San Francisco Chronicle—one riding in the Muni Metro tunnel and one on foot on the surface—held a race through downtown, with the walking reporter emerging the winner.[33]

After initial problems with the ATC were fixed, substantial upgrades to the entire Muni transit systems have gone a long way towards resolving persistent crowding and scheduling issues. Nonetheless, Muni remains one of the slowest urban transport systems in the United States.

Recent expansion

In 1980, the M Ocean View was extended from Broad Street and Plymouth Avenue to its current terminus at Balboa Park.[6] In 1991, the J Church was extended from Church and 30th Streets to its current terminus at Balboa Park.[6] In 1998, the N Judah was extended from Embarcadero Station to the planned site of the new Pacific Bell Park and Caltrain Depot,[34] after that extension was briefly served between January and August of that year by the temporary E Embarcadero[35][36] light rail shuttle (restored in 2015 as the E Embarcadero heritage streetcar line).

In 2007, the T Third Street, running south from Caltrain Depot along Third Street to the southern edge of the city, opened as part of the Third Street Light Rail Project. Limited weekend T line service began on January 13, 2007, while full service began on April 7, 2007. The line initially ran from the southern terminus at Bayshore Boulevard and Sunnydale Street to Castro Street Station in the north. The line ran into initial problems with breakdowns, bottlenecks, and power failures, creating massive delays.[37] Service changes to address complaints with the introduction of the T Third Street were implemented on June 30, 2007, when the K and T trains were interlined, or effectively merged into one single line with route designations changing at the entrances into the subway (T becomes K outbound at Embarcadero; K becomes T inbound at West Portal).[38]

COVID-19 Pandemic

On March 30, 2020, Muni Metro service was replaced with buses due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[39] Rail service returned for several days on August 22, with the routes reconfigured to improve reliability in the subway: K Ingleside and L Taraval service are interlined, running between Wawona and 46th Avenue station and Balboa Park station; no K or L service enters the subway. J Church service runs only on the surface between Balboa Park station and Church and Duboce station. M Ocean View and T Third Street service are interlined, running between Sunnydale station and Balboa Park station; it runs in the subway along with normal N Judah service and increased S Shuttle service.[40] The forced transfers at West Portal and Church stations were criticized by disability advocates.[41] Muni Metro service was again indefinitely replaced by buses on August 25, 2020, due to malfunctioning overhead wire splices and the need to quarantine control center staff after a COVID-19 case.[42][43]

Future expansion

Several expansion projects are underway or under study. Federal funding has been secured for, and construction has begun on, the Central Subway,[44] a combined surface and subway extension of the T Third line, running from Caltrain Depot to Chinatown, with stops at Moscone Center and Union Square, and with the potential for a future expansion to North Beach and Fisherman's Wharf.[45] Muni estimates that the Central Subway section of the T Third line will carry roughly 35,100 riders per day by 2030.[46] The Central Subway is projected to be complete and ready for revenue service in late 2021 at a projected cost of $1.578 billion.[46][47] Once the Central Subway is complete, it may also continue as an above-ground light rail line through North Beach, and into the Marina district, with the possibility of eventually terminating in the Presidio.[48]

A project to grant the M Ocean View its own separated right-of-way called the Muni Subway Expansion Project, building off of a 2014 SFCTA study, is undergoing preliminary engineering studies by the SFMTA as of 2018.[49][50] The project would extend the Muni subway service in a tunnel under 19th Avenue, providing grade-separated service from Embarcadero station to a proposed Park Merced station.

The 20-year Capital Plan for the SFMTA also lists both a Geary Light Rail project (a surface-subway light rail line to the Richmond District via Geary Boulevard) and a Geneva Avenue Light Rail project (a light rail line connecting Balboa Park station to the terminus of the T Third line).[51]

Infrastructure

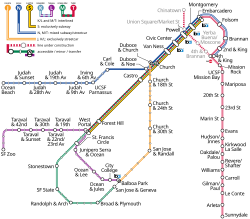

The Muni Metro system consists of 71.5 miles (115.1 km) of standard gauge track, seven light rail lines (six regular lines and one peak-hour line), three tunnels, nine subway stations, 24 surface stations, and 87 surface stops.[52]

The backbone of the system is formed by two interconnected subway tunnels, the older Twin Peaks Tunnel and the newer Market Street subway, both controlled by automatic train operation systems to run trains with the operators closing the door to allow the train to pull out of a station. This ATO system was upgraded in 2015 to replace outdated software and relays.[53] The tunnels, 5.5 miles (8.9 km) in total length,[6] run from West Portal Station in the southwestern part of the city to Embarcadero Station in the heart of the Financial District. Three lines—the K Ingleside, the L Taraval, and the M Ocean View—feed into the tunnel at West Portal, while two lines, the J Church and N Judah, enter at a portal near Church Street and Duboce Avenue in the Duboce Triangle neighborhood. Two lines, the N Judah and T Third Street, enter and exit the tunnel at Embarcadero. An additional tunnel, the Sunset Tunnel, is located near the Duboce portal and is served by the N.

The interconnected tunnels contain nine subway stations.[1] Three stations—West Portal, Forest Hill and the now-defunct Eureka Valley—were opened in 1918 as part of the Twin Peaks Tunnel,[54] while the other seven—Castro Street, Church Street, Van Ness, Civic Center, Powell Street, Montgomery Street and Embarcadero—were opened in 1980 as part of the Market Street subway. Four stations, Civic Center, Powell Street, Montgomery Street, and Embarcadero, are shared with Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), with Muni Metro on the upper level and BART on the lower one.[55]

Above ground, there are twenty-four surface platform stations.[1] Two stations, Stonestown and San Francisco State University are located at the southwestern part of the city, while the rest are located on the eastern side of the city, where the system underwent recent expansion as part of the Embarcadero extension and the Third Street Light Rail Project. However, many of the stops on the system are surface stops consisting of anything from a traffic island to a yellow-banded "Car Stop" sign painted on a utility pole.[56]

All subway and surface stations are handicap-accessible. In addition, several surface street stops are also handicap-accessible, often consisting of a ramp leading up to a small platform for boarding.[57]

In Muni Metro terminology, an inbound train is one that heads from the western neighborhoods and West Portal towards Embarcadero, while an outbound train travels in the opposite direction out of downtown towards the west. Even the T Third Street line is consistent with this terminology, with an inbound train going from West Portal through Embarcadero to Sunnydale, and an outbound train running out of the southeastern neighborhoods into downtown.[58]

Muni Metro has two rail yards for storage and maintenance:

- Green Yard or Curtis E. Green Light Rail Center at 425 Geneva Avenue is located adjacent to Balboa Park Station and serves as the outbound terminus for the J Church, K Ingleside, and M Ocean View. The facility has repair facilities, an outdoor storage yard and larger carhouse structure. The facility was renamed for former and late head of Muni in 1987.[59]

- Muni Metro East is a newer facility opened in 2008 and is located along the Central Waterfront on Illinois and 25th Streets in the Potrero Hill neighborhood, a block from the T Third Street line.[60] The 180,000-square-foot (17,000 m2) maintenance facility with outdoor storage area is located next to Northern Container Terminal and former Army Pier.

Routes

| Line | Year opened[6][61] |

Termini | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inbound | Outbound | |||

| J Church | 1917 | Church and Market | Balboa Park | |

| K Ingleside | 1918 | West Portal (continues as L Taraval) |

Balboa Park | |

| L Taraval | 1919 | West Portal (continues as K Ingleside) |

Wawona and 46th Avenue (SF Zoo) | |

| M Ocean View | 1925 | Embarcadero (continues as T Third Street) |

San Jose and Geneva (Balboa Park) | |

| N Judah | 1928 | 4th and King | Judah and La Playa (Ocean Beach) | |

| S Shuttle | 2001 | Embarcadero | West Portal | |

| T Third Street | 2007 | Sunnydale | West Portal (continues as M Ocean View) | |

Rolling stock

| Manufacturer | Boeing Vertol | Breda | Siemens Mobility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | US SLRV | San Francisco LRV | S200 SF |

| Muni designation | LRV1 | LRV2/3[a] | LRV4 |

| Image |

|

|

|

| Dates in Service | 1979–2002 | 1996–2027 (projected) | 2017– |

| Quantity | 131[b] | 151[c] | 219 (264)[d] |

| Trucks/Axles | 3 trucks (2 powered), 6 axles (total) | ||

| Articulations | 1 | ||

| Length | 73 feet (22 metres) |

75 feet (23 metres) | |

| Width | 8 feet 10 inches (2.69 metres) |

9 feet (2.7 metres) |

8 feet 8.32 inches (2.65 metres) |

| Height | 11 feet 6 inches (3.51 metres) | ||

| Weight (empty) | 67,000 pounds (30,000 kilograms) |

79,580 pounds (36,100 kilograms)[74] |

78,770 pounds (35,730 kilograms) |

| Power | 2×210 hp (160 kW) DC motors | 4×130 hp (97 kW) AC motors | 4×174 hp (130 kW) motors |

| Capacity | 68 (seated) 219 max |

60 (seated) 218 max |

60 (seated) 203 max |

Notes

- ^ LRV3 cars were delivered starting in 1999; the LRV3s featured some minor design changes that were later retrofitted to the earlier LRV2s.[67]

- ^ Original order of 80 expanded to 100. 31 additional vehicles were purchased from a lot of 40 rejected by MBTA, the other operator using SLRVs

- ^ Original order of 35 (12/1991) expanded to 151 by exercising options: +5 (40 total, 11/1992); +4 (44 total, 5/1993); +8 (52 total, 12/1993); +25 (77 total, 4/1996). The last 74 (ordered as +59, 10/1998; +15, 5/1999) were delivered as LRV3 vehicles starting in 1999.[67]

- ^ Total firm orders are for 219 vehicles. The 264 vehicles are broken down as: 151 to replace the Breda LRV2/3 fleet, 24 for Central Subway service, and 89 more for projected increases in ridership. Of the 219 firm orders, the first order in 2014 was for 175 (151+24),[68] Muni exercised its option on an additional 40 LRV4s in June 2015[69] and ordered 4 more LRV4s in June 2017 for anticipated Warriors service (Phase W).[70] The first 68 vehicles are designated the "future fleet": 24 Central Subway cars (Phase 1), 40 expansion LRV4s (Option 1), and 4 LRV4s (Phase W). The 68-car "future fleet" procurement is expected to complete delivery by October 2019.[71] The next cars to be delivered, starting in 2021, will be the 151 "replacement fleet" LRV4s (Phase 2) to retire the existing Breda fleet.[72] As of June 2018, 20 cars are in revenue service and 10 are in testing.[73]

LRV 1: Boeing Vertol US SLRV (1979–2002)

Muni Metro first operated Boeing Vertol-made US Standard Light Rail Vehicles (USSLRV), which were built for Muni Metro and Boston's MBTA.[75][76] Boeing had no experience in making LRVs,[75] and has not made another since.[76] The first cars of the initial 100-car order arrived in San Francisco in 1978; Boston had been running the cars since 1976 and by 1978, MBTA was already returning 35 cars for manufacturing defects.[75] After receipt of the first cars, MBTA forced Boeing to make 70 to 80 modifications on each car. Boeing ended up paying US$40,000,000 (equivalent to $214,175,439 in 2023) in damages to Boston.[75] The purchase price for each car was US$333,000 (equivalent to $1,555,586 in 2023).[75]

The federal government offered to provide 80% of the funds for design and production of the USSLRV[76] in exchange for a commitment to keep the cars in service for at least 25 years,[75] but the cars, as-delivered, were prone to jammed doors, defective brakes and motors, leaky roofs, mechanical breakdowns, and were involved in several accidents.[75] Muni Metro added 30 more cars to the fleet; these 30 had been rejected by MBTA after suffering numerous breakdowns.[76][77]

In 1982, the Boeing cars averaged only 600 miles (970 km) between breakdowns; by 1988 this had improved to 1,800 to 2,000 miles (2,900 to 3,200 km) between breakdowns.[75] In 1998, Rudy Nothenberg, president of the Public Transportation Commission, said the Boeing cars were "impossible to maintain and [...] have many, many design flaws;"[75] that same year, Muni was only able to supply 66–72 working cars for rush-hour service instead of the required 99 cars, resulting in system delays.[77] Despite the shortcomings of the USSLRV design, these cars constituted the entire light rail fleet until 1996, when new Breda-manufactured cars were put into service,[78] replacing Boeing cars as they were accepted for service.[75] By 1998, the 136-car Muni Metro fleet consisted of 57 Boeing Vertol cars and 79 Breda cars.[75]

Two Boeing cars were preserved for potential donation to the San Francisco Railway Museum, but have since been scrapped;[79] five were sold to the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Authority for the modest price of US$200 (equivalent to $338.8 in 2023) to US$500 (equivalent to $846.99 in 2023) each; one was acquired by the Oregon Electric Railway Historical Society in 2001, but the Society declined to take any more Boeing cars after experiencing several breakdowns.[76] Boeing car no. 1258 has been on exhibit at the Western Railway Museum near Suisun City since its acquisition in 2002.[62]

LRV 2 & LRV 3: Breda (1996–present)

at 42nd Avenue

at 42nd AvenueThe first of four prototypes of the new Breda cars was delivered in January 1995.[80] After delivery of additional cars and training of operators, the cars began to enter service on December 10, 1996. They were the most expensive street railway vehicles built to-date, at a cost of US$2,000,000 (equivalent to $3,885,423 in 2023) each, and they were assembled at Pier 80.[78] After suffering initial breakdowns[81] and despite facing complaints of noise and vibrations,[82][83] the Bredas gradually replaced the Boeings, with the last Boeing car being retired in 2002.[76] Residents along streetcar lines complained the new Breda cars would screech during acceleration and deceleration and their 80,000-pound (36,000 kg) weight, 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) heavier than the Boeing cars,[82] was blamed for vibration issues.[83] At one point in 1998, 12 Breda cars were unavailable for service due to door problems.[81] Faulty couplers on the Breda cars have been blamed for reduced train capacity, as multiple cars are not able to be coupled together as intended.[74]

Muni originally ordered 35 cars from Breda in 1991, and exercised options to add another 116 cars throughout the 1990s, including an option to purchase another 15 cars in 1999.[67][84] The fleet had 151 LRVs in 2014, all made by Breda.[3][85] The double-ended cars are 75 feet (23 m) long, 9 feet (2.7 m) wide, 11 feet (3.4 m) high, have graffiti-resistant windows, and contain an air-conditioning system to maintain a temperature of 72 °F (22 °C) inside the car.[86] The Breda cars feature four doors per car, versus three for the Boeing (only the middle two doors of the Boeing cars were available while in the tunnels due to the cars' end curvature).[78] The initial batch of 136 Breda cars were ordered on contracts exceeding US$320,000,000 (equivalent to $585,281,662 in 2023), for an average per-car cost of US$2,350,000 (equivalent to $4,298,162 in 2023); the option of 15 additional cars was exercised on a contract worth US$42,300,000 (equivalent to $77,366,920 in 2023), making the last batch of 15 cars US$2,600,000 (equivalent to $4,755,414 in 2023) each.[84]

By 2011, the fleet of Breda LRVs was only able to manage a mean distance between failures (MDBF) of 617 mi (993 km).[87][88]

LRV 4: Siemens S200 SF (2017–present)

With the Breda' cars growing increasingly unreliable, and the system growing with the construction of the Central Subway, Muni requested bids for a new generation of light rail vehicles. Muni prequalified CAF, Kawasaki, and Siemens to bid on the request, while Breda was disqualified based on a ranking of potential bidders.[85]

The contract was awarded to Siemens for the purchase of up to 260 cars, to be delivered in three phases: the initial firm order of 24 cars would be accommodate the Central Subway, the next firm order of 151 cars would replace all of the Breda vehicles, and an option to purchase up to 85 additional cars, funding permitting, to accommodate projected ridership growth through 2040.[89][85] Muni ultimately purchased 219 vehicles: the 175 cars from the first two phases and 44 additional cars.[90]

Upon awarding the contract, Muni officials cited several lessons learned from the prior Breda contract, including not buying enough cars, dictating too much of the design, lax reliability requirements, and a failure to account for maintenance costs.[89] The US$648,000,000 (equivalent to $834,001,687 in 2023) contract for 175 cars (the first two phases) was signed by Mayor Ed Lee in September 2014, making the cost of each car approximately US$3,700,000 (equivalent to $4,762,047 in 2023).[91]

A grant of $41 million from the California Transportation Agency awarded on July 2, 2015 to allowed Muni to purchase 40 additional Siemens light rail vehicles.[92]

Design

Siemens has named the new Muni cars the S200 SF, while the SFMTA refers to them as the LRV4. They operate at speeds of up to 50 miles per hour (80 km/h).[66] The S200 SF is 75 feet (23 m) long, 8 feet 8.32 inches (2.65 m) wide, 11 feet 6 inches (3.51 m) high (with the pantograph locked down), and weighs 78,770 pounds (35,730 kg), making it comparable in size and weight to the existing Breda cars.[66] The expected maximum capacity is 203 passengers per car.[66] They are expected to have the same coupling device as the Breda cars, however, the new Siemens trains can couple up to five cars at a time.[3][89][66] The new S200 SF vehicles are projected to be able to run 59,000 miles (95,000 km) between maintenance intervals.[93] Initially, the new cars had a mean distance between failures (MDBF) of 3,300 mi (5,300 km) shortly after being delivered; by August 2019, the MDBF had improved to 8,000 mi (13,000 km).[71]

Service history

Siemens publicly unveiled a full-size mockup of the S200 SF in San Francisco on June 16, 2015.[94] The first car was delivered from the Siemens plant in Sacramento to San Francisco on January 13, 2017. A test car passed a CPUC regulatory inspection in early November 2017 and car #2006 was the first LRV to enter revenue service on November 17, 2017, following a ribbon-cutting ceremony at Duboce and Church.[95]

The first 68 cars were used to expand the Muni fleet to 219 cars and once the fleet reached that total in October 2019, Breda cars would be retired as new Siemens cars are accepted.[96][90]

It is expected that deliveries of cars will continue through 2028.[93]

Fares and operations

Muni Metro runs from approximately 5 am to 1 am weekdays, with later start times of 7 am on Saturday and 8 am on Sunday.[97] Owl service, or late-night service, is provided along much of the L and N lines by buses that bear the same route designation.[97]

The cash fare for Muni Metro, like Muni buses, effective January 1, 2020, is $3 for adults and $1.50 for youth ages 5–17, seniors, and the disabled. Clipper and MuniMobile fares are lower than cash fares. Their fares are $2.50 for adults and $1.25 for youth ages 5–17, seniors, and the disabled.[98]

Muni currently operates a Free Muni for Seniors program that provides low- and moderate-income seniors residing in San Francisco free access to all Muni transit services, including Muni's cable cars. Free Muni is open to all San Francisco senior Clipper card holders, ages 65 and over, with a gross annual family income at or below 100 percent of the Bay Area Median Income level (qualifying income levels are posted on the program's web page). Enrollment is not automatic. To participate in the program, a qualified senior must have or obtain a Clipper card and submit an application either online or by mail.

Like Muni buses, the Muni Metro operates on a proof-of-payment system;[99] on paying a fare, the passenger will receive a ticket good for travel on any bus, historic streetcar, or Metro vehicle for 120 minutes.[100] Payment methods depend on boarding location. On surface street sections in the south and west of the city, passengers must board at the front of the train and pay their fare to the train operator to receive their ticket; those who already have a ticket, or who have a daily, weekly, or monthly pass, can board at any door of the Metro streetcar.[99] Subway stations have controlled entries via faregates, and passengers usually purchase or show Muni staff a ticket in order to enter the platform area. Faregates closest to an unmanned Muni staff booth open automatically if a passenger has a valid pass or transfer that cannot be scanned.[99] Muni's fare inspectors may board trains at any time to check for proof of payment from passengers.[99]

All cars are also equipped with Clipper card readers near each entrance, which riders may use to tag their cards to pay their fare. The cards themselves are then used as proof of payment; fare inspectors carry handheld card readers that can verify that payment was made. In subway stations, riders instead tag their cards on the faregates to gain access to the platforms.

See also

- Market Street Railway and other rail lines operated by MUNI:

- SelTrac, the automated train system used in the Market Street subway

- Light rail in the United States

- Streetcars in North America

- List of United States light rail systems by ridership

- List of North American light rail systems by ridership

- List of California railroads

- List of tram and light rail transit systems

References

- ^ a b c "San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Capital Investment Plan — FY 2009–2013" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. August 15, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 5, 2009. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- ^ a b c "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter and End-of-Year 2017" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 13, 2018. Archived from the original (pdf) on March 27, 2018. Retrieved July 4, 2018.

- ^ a b c "2010 SFMTA Transit Fleet Management Plan" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved March 3, 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c "San Francisco LRV Specifications" (PDF). Ansaldobreda. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ Chinn, Jerold (August 23, 2017). "Muni to seek approval for four-car subway trains". SF Bay. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Demery, Jr., Leroy W. (November 2011). "U.S. Urban Rail Transit Lines Opened From 1980" (PDF). publictransit.us. Archived from the original (pdf) on November 4, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ "San Francisco Muni: Unique Cost/Operating Environment" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. July 26, 2007. Archived from the original (pdf) on February 5, 2009. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Reisman, Will (December 14, 2010). "Muni Metro trackway trouble unresolved". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy, M.M. (1921). The municipal railway of San Francisco, 1912–1921. San Francisco, California: J.A. Prudhomme Composition Co. p. 9. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ "A Brief History of the F-Market & Wharves Line". Market Street Railway. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "Streetcars: The A Line". Western Neighborhoods Project. May 22, 2002. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy (1921),p. 18

- ^ Wallace, Kevin (March 27, 1949). "The City's Tunnels: When S.F. Can't Go Over, It Goes Under Its Hills". San Francisco Chronicle. SFGenealogy. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ O'Shaughnessy (1921), p. 5

- ^ "N Judah Streetcar Line". Western Neighborhoods Project. October 18, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Muni's History". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ^ "This Is Light Rail Transit" (PDF). Light Rail Transit Committee. Transportation Research Board. November 2000. p. 7. Archived from the original (pdf) on February 21, 2018. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ^ "Rapid Transit for the San Francisco Bay Area" (PDF). LA Metro Library. Parsons Brinkerhoff / Tudor / Bechtel. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- ^ Perles, Anthony (1981). The People's Railway: The History of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Glendale, CA (US): Interurban Press. p. 250. ISBN 0-916374-42-4.

- ^ McKane, John; Perles, Anthony (1982). Inside Muni: The Properties and Operations of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Glendale, CA (US): Interurban Press. pp. 189–202. ISBN 0-916374-49-1.

- ^ a b Soiffer, Bill (September 20, 1982). "The Last Streetcar On Top of Market". San Francisco Chronicle, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Perles, Anthony (1984). Tours of Discovery: A San Francisco Muni Album. Interurban Press. pp. 126, 136. ISBN 0-916374-60-2.

- ^ "Chapter 1". Muni Metro Turnaround Project: Final Enivironmental Impact Statement. United States Department of Transportation Urban Mass Transportation Administration. August 1989. pp. 1–3 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Hendricks, Tyche (September 22, 1998). "Muni relief delayed till next year". San Francisco Examiner. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (April 22, 1999). "Muni Investing in More Breda Streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ a b McCormick, Erin (April 21, 1997). "Muni rolling out first of new fleet of streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ "J-Line Residents Ready to Rumble Over Breda Cars". The Noe Valley Voice. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ "Coupling without orders is technically an avoidable accident". Rescue MUNI. Archived from the original on September 20, 2000. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (August 14, 1997). "Muni Plans to Quiet Streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ "Fundamental Flaws Derail Hopes of Improving Muni". San Francisco Chronicle. June 23, 1997. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ^ "Real-time Subways". Gin and Tonic. 2004. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ^ "EBs in the Subway—ARRGH". Rescue Muni. 1998. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Epstein, Edward; Rubenstein, Steve (September 1, 1998). "A Walker Matches Train Pace". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (August 26, 1998). "Brown Tries To Soothe Muni Riders / Service on N-Judah line has been abysmal all week – SFGate". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Epstein, Edward (January 9, 1998). "Embarcadero Line On Track Tomorrow". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A-17. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ Taylor, Michael (April 6, 1998). "PAGE ONE – Muni's New E-Line No Beeline / Trains more tardy, irregular than buses – SFGate". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel (April 12, 2007). "Passengers Left in Lurch By T-Third's Rough Start". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A-1. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ^ "Service Changes Effective June 30, 2007". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. 2007. Archived from the original on October 24, 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ^ Fowler, Amy (March 26, 2020). "Starting March 30: New Muni Service Changes" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ Maguire, Mariana (August 18, 2020). "Major Muni Service Expansion August 22" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency.

- ^ Graf, Carly (August 18, 2020). "Muni 'improvements' could make things harder for seniors, disabled". San Francisco Examiner.

- ^ "Bus Substitution for All Rail Lines" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. August 25, 2020.

- ^ Graf, Carly (August 24, 2020). "Muni tells train riders to get back on the bus". San Francisco Examiner.

- ^ "San Francisco's Central Subway Project Receives Outstanding Rating from FTA". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Archived from the original on October 12, 2008. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ Vega, Cecilia M. (February 20, 2008). "S.F. Chinatown subway plan gets agency's nod". San Francisco Chronicle. p. B-1. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- ^ a b "FAQS MTA Central Subway". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Central Subway Update – Projected to be Open for Service by the End of 2021" (Press release). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. June 5, 2020.

- ^ "T-Third Phase 3 Concept Study" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "19th Avenue Transit Study". San Francisco County Transportation Authority. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "Muni Subway Expansion Project". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "SFMTA 20-year Capital Plan" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. 2017. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ "Muni Metro Light Rail". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (May 10, 2015). "Tech in the tunnels: Muni train control system gets biggest upgrade since the '90s". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- ^ "West of Twin Peaks". Western Neighborhoods Project. May 9, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ^ Bei, R. (1978). "San Francisco's Muni Metro, A Light-Rail Transit System". TRB Special Report No. 182, Light-Rail Transit: Planning and Technology. Transportation Research Board. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ^ "Info for New Riders: How do I find a bus stop?". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ^ "Muni Metro accessibility". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Route Description for T Third Street". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (June 24, 2011). "Curtis E. Green – rose from bus driver to head of S.F. Muni". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Gordon, Rachel (September 17, 2008). "S.F. streetcars get a new maintenance yard". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Demery, Jr., Leroy W. (October 25, 2010). "U.S. Urban Rail Transit Lines Opened From 1980: Appendix". publictransit.us. Archived from the original on November 3, 2013. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ^ a b "San Francisco Municipal Railway 1258". Western Railway Museum. May 5, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ URS Corporation (January 22, 2009). Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Extension of Historic Streetcar Service from Fisherman's Wharf to the San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park and Golden Gate National Recreation Area's Fort Mason Center (PDF) (Report). National Park Service – Golden Gate National Recreation Area. p. 7. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "Light Rail, San Francisco". AnsaldoBreda. 2011. Archived from the original on September 4, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ "San Francisco LRV" (PDF). AnsaldoBreda. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e "S200 SF Light Rail Vehicle" (PDF). Siemens Industry, Inc.; Rolling Stock Division. May 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Requesting authorization for the Director of Transportation to execute a Closeout and Settlement Agreement with AnsaldoBreda SpA for Contract No. 309, Procurement of Light Rail Vehicles" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. February 11, 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 27, 2018. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Resolution No. 14-120" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. July 15, 2014. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Approving programming of up to $210 million to exercise the Option 1 for 40 additional light rail vehicles (LRVs) under Contract #2013-19 with Siemens Industry, Inc. (Siemens)" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. January 9, 2015. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "Resolution No. 170620-081" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, Board of Directors. June 20, 2017. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (September 24, 2019). "New Muni trains breaking down far less often". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ "Authorizing the Director of Transportation to execute Contract Modification No. 4 to SFMTA Contract No. 2013-19: Procurement of New Light Rail Vehicles (LRV4), with Siemens Industry, Inc" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. June 14, 2017. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ "FY 17–18 Quarterly Project Status Report: Procurement of New Light Rail Vehicles (LRV4)" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved December 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Eskenazi, Joe (October 2, 2015). "Can a $1.2 Billion Fleet of New Trains Finally Save Muni?". San Francisco Magazine. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Sullivan, Kathleen (September 14, 1998). "Muni knew about trolley lemons in '70s". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f Lelchuk, Ilene (January 14, 2002). "Muni cars on a roll into city junkyard". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Nolte, Carl (September 21, 1998). "Fundamental Flaws Derail Hopes of Improving Muni". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c Nolte, Carl (December 10, 1996). "Stylish New Streetcars Ready to Roll". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (March 31, 2016). "Last of Muni's 1980s-era clunker trains will be scrapped". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved January 24, 2017.

- ^ Wolinsky, Julian, ed. (March 1995). "Commuter [transit-news section]". Passenger Train Journal. Pentrex. pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b Epstein, Edward; Lynem, Julie N. (August 29, 1998). "Brown Descends To Take Hellish Journey on Muni". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Epstein, Edward (July 9, 1997). "Streetcar Racket Figures in Contract". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ a b Epstein, Edward (October 6, 1998). "U.S. to Pay for 59 Streetcars For Muni From Italy's Breda". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Epstein, Edward (April 22, 1999). "Muni Investing in More Breda Streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b c Cabanatuan, Michael (September 17, 2013). "New ride coming to Muni Metro". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Salter, Stephanie (January 26, 1997). "Beefy, but they whine". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ^ Stevenson, Peg; Lapka, Joe (June 3, 2014). City Services Benchmarking: Public Transportation (PDF) (Report). City Services Auditor, Office of the Controller, City & County of San Francisco. pp. 15–17. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ Bialick, Aaron (June 5, 2014). "Muni's Abysmal Breakdown Rate: One Reason SF Needs a Vehicle License Fee". Streetsblog SF. Retrieved September 25, 2019.

- ^ a b c Cabanatuan, Michael (July 16, 2014). "$1.2 billion contract OKd for new Muni Metro light-rail cars". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ^ a b Kirschbaum, Julie (November 19, 2019). LRV4 Project Update (PDF) (Report). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Cabanatuan, Michael (September 20, 2014). "Mayor signs deal for new fleet of Muni Metro railcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Chinn, Jerold (July 2, 2015). "Muni secures $41 million for new Metro trains". Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ a b Rubenstein, Steve (January 13, 2017). "First in fleet of new Muni Metro car arrives in San Francisco". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ Vantuono, William C. (June 16, 2015). "Siemens S200 SF previews in San Francisco; more LRVs ordered". Railway Age. Retrieved August 27, 2015.

- ^ Robertson, Michelle (November 17, 2017). "New Muni train, designed to be quieter and more spacious, hit San Francisco streets". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ Thompson, Walter (May 18, 2016). "These new Muni Metro cars should be ready to roll next year". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved January 18, 2017.

- ^ a b "Muni Metro Service". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- ^ https://www.sfmta.com/getting-around/muni/fares

- ^ a b c d "Proof of Payment". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. February 4, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ^ "Fares and Sales". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Archived from the original on February 5, 2007. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

External links

![]() Media related to Muni Metro at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Muni Metro at Wikimedia Commons

- Muni Metro performance statistics

- http://sfmunicentral.com/Enterprise/MetroLO.htm – Live display of trains in the subway, has train numbers, routes, and train paths.