Kombucha

Kombucha including the culture | |

| Type | Cold beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Unknown; possibly Manchuria |

Kombucha (also tea mushroom, Manchurian mushroom, formal name: Medusomyces gisevii[1]) is a variety of fermented, lightly effervescent sweetened black or green tea drinks commonly intended as functional beverages for their supposed health benefits. Kombucha is produced by fermenting tea using a "symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast" (SCOBY). Actual contributing microbial populations in SCOBY cultures vary, but the yeast component generally includes Saccharomyces and other species; and, the bacterial component almost always includes Gluconacetobacter xylinus to oxidize yeast-produced alcohols to acetic and other acids.[2][3]

Although numerous sources have linked drinking kombucha to health benefits, there is little or no scientific evidence backing those claims.[4] There are rare documented cases of serious adverse effects, including fatalities, related to kombucha drinking, possibly arising from contamination during home preparation.[5][6] Since the mostly unclear benefits of kombucha drinking do not outweigh the known risks, it is not recommended for therapeutic use.[4] Kombucha tea made with less sugar may be unappealing.[7]

The exact origins of kombucha are not known.[8] It is said to have originated in what is now Manchuria, and was traditionally used primarily in that region, Russia, and eastern Europe.[9] Kombucha is home-brewed globally and some companies sell it commercially.[1]

Health claims

According to a 2000 review, "It has been claimed that Kombucha teas cure asthma, cataracts, diabetes, diarrhea, gout, herpes, insomnia and rheumatism. They are purported to shrink the prostate and expand the libido, reverse grey hair, remove wrinkles, relieve haemorrhoids, lower hypertension, prevent cancer, and promote general well-being. They are believed to stimulate the immune system, and have become popular among people who are HIV positive or have full-blown AIDS".[2] People drink it for its many putative beneficial effects, but most of the benefits were merely experimental studies and there is little scientific evidence based on human studies.[1] There have not been any human trials conducted to confirm any curative claims associated with the consumption of kombucha tea.[1] There is no high-quality evidence of beneficial effects from consuming kombucha.[4]

A 2003 systematic review characterized kombucha as an "extreme example" of an unconventional remedy because of the great disparity between implausible, wide-ranging health claims lacking evidentiary support, and the potential for harm kombucha has.[4] Ernst concluded that the number of proposed, unsubstantiated, therapeutic benefits did not outweigh the known risks, and that kombucha should not be recommended for therapeutic use.[4] Kombucha only appears to benefit those who profit from them, according to a 2003 review.[4]

Adverse effects

Reports of adverse effects related to kombucha consumption are rare. It is unclear whether this is because adverse effects are rare, or just underreported.[4] The American Cancer Society says that "Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been associated with drinking Kombucha tea".[6]

Adverse effects associated with kombucha consumption include severe hepatic (liver) and renal (kidney) toxicity as well as metabolic acidosis.[10][11][12] At least one person is known to have died after consuming kombucha, though the drink itself has never been conclusively proved a cause of death.[13][14]

Some adverse health effects may be due to the acidity of the tea, which can cause acidosis, and brewers have been cautioned to avoid over-fermentation.[15][16][17] Other adverse health effects may be a result of bacterial or fungal contamination during the brewing process.[17] Some studies have found the hepatotoxin usnic acid in kombucha, although it is not known whether the cases of damage to the liver are due to the usnic acid contamination or to some other toxin.[11][18] Topical use of the tea has been associated with anthrax infection on the skin in one report, but kombucha contamination may have occurred during storage.[4]

Drinking Kombucha can be harmful for people with preexisting ailments.[19] Due to its microbial sourcing and possible non-sterile packaging, kombucha is not recommended for people with poor immune function,[15] women who are pregnant or nursing, or children under 4 years old.[17] Further, it may compromise immune responses or affect stomach acidity in susceptible people.[15]

Other uses

Kombucha culture, when dried, becomes a leather-like textile known as a microbial cellulose that can be molded onto forms to create seamless clothing.[20][21] Using different broth media such as coffee, black tea, and green tea to grow the kombucha culture results in different textile colors, although the textile can also be dyed using plant-based dyes.[22] Different growth media and dyes also change the textile's feel and texture.[22]

Composition and properties

Biological

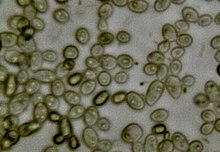

A kombucha culture is a symbiotic culture of bacteria and yeast (SCOBY), similar to mother of vinegar, containing one or more species each of bacteria and yeasts, which form a zoogleal mat[23] known as a "mother."[1] The cultures may contain one or more of the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Brettanomyces bruxellensis, Candida stellata, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, and Zygosaccharomyces bailii.[24]

The bacterial component of kombucha comprises several species, almost always including Gluconacetobacter xylinus (G. xylinus, formerly Acetobacter xylinum), which ferments alcohols produced by the yeasts into acetic and other acids, increasing the acidity and limiting ethanol content.[citation needed] The population of bacteria and yeasts found to produce acetic acid has been reported to increase for the first 4 days of fermentation, decreasing thereafter.[citation needed] G. xylinus has been shown to produce microbial cellulose, and is reportedly responsible for most or all of the physical structure of the "mother", which may have been selectively encouraged over time for firmer (denser) and more robust cultures by brewers.[25][non-primary source needed]

The mixed, presumably symbiotic culture has been further described as being lichenous, in accord with the reported presence of the known lichenous natural product usnic acid, though as of 2015, no report appears indicating the standard cyanobacterial species of lichens in association with kombucha fungal components.[18]

Chemical

It is made by putting the kombucha culture into a broth of sugared tea.[1] Kombucha tea made with less sugar may be unappealing.[7] Sucrose is converted, biochemically, into fructose and glucose, and these into gluconic acid and acetic acid, and these substances are present in the drink.[26] In addition, kombucha contains enzymes and amino acids, polyphenols, and various other organic acids; the exact quantities of these items vary between preparations. Other specific components include ethanol (see below), glucuronic acid, glycerol, lactic acid, usnic acid (a hepatotoxin, see above), and B-vitamins.[27][28][29] Kombucha has also been found to contain vitamin C.[30]

The alcohol content of the kombucha is usually less than 1%, but increases with fermentation time.[17] Over-fermentation generates high amounts of acids similar to vinegar.[1]

History

The exact origins of kombucha are not known, although Manchuria is commonly cited as a likely place of origin.[8] It may have originated as recently as 200 years ago or as long as 2000 years ago.[31] The drink is reported to have been consumed in east Russia at least as early as 1900, and from there entered Europe.[26] In 1913, kombucha was first mentioned in German literature.[32] Its consumption increased in the United States during the early 21st century.[31][33] Having an alcohol content of about 0.5%, kombucha is a federally regulated beverage in the United States, a factor that affected its commercial development in 2015.[34]

Etymology

The word kombucha is of uncertain etymology, but may be a case of a misapplied loanword from Japanese.[35] In Japanese, the term kombucha (昆布茶, "kelp tea") refers to a completely different beverage, the kelp tea, made from dried and powdered kombu (an edible kelp from the Laminariaceae family). The term for the fermented tea in Japanese, is kōcha kinoko (紅茶キノコ, "fungus tea").[36]The American Heritage Dictionary suggests that it is probably from the "Japanese kombucha, tea made from kombu (the Japanese word for kelp perhaps being used by English speakers to designate fermented tea due to confusion or because the thick gelatinous film produced by the kombucha culture was thought to resemble seaweed)."[37] Writings about the beverage in Japanese generally take the point of view that the Japanese word 'kombucha' was mistakenly applied in English to what Japanese call "kocha kinoko."

Kombucha has about 80 other names worldwide.[38] A 1965 mycological study called kombucha "tea fungus" and listed other names: "teeschwamm, Japanese or Indonesian tea fungus, kombucha, wunderpilz, hongo, cajnij, fungus japonicus, and teekwass".[39] Some further spellings and synonyms include combucha and tschambucco, haipao, kargasok tea, kwassan, Manchurian fungus or mushroom, spumonto, as well as the misnomers champagne of life, and chai from the sea.[15]

Production

Kombucha drink is prepared at home globally and some companies sell it commercially.[1] Commercially bottled kombucha became available in the late 1990s.[40] In 2010, elevated alcohol levels were found in many bottled kombucha products, leading retailers including Whole Foods to temporarily pull the drinks from store shelves.[41] In response, kombucha suppliers reformulated their products to have lower alcohol levels.[42]

By 2014 US sales of bottled kombucha were $400 million; $350 million of that was earned by Millennium Products, Inc. which sells "GT's Kombucha".[43] In 2014, the market was projected to have 30% growth, and companies that make and sell kombucha formed a trade organization, Kombucha Brewers International.[44] In 2016, PepsiCo purchased kombucha maker KeVita for approximately $200 million.[45]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jayabalan, Rasu (21 June 2014). "A Review on Kombucha Tea—Microbiology, Composition, Fermentation, Beneficial Effects, Toxicity, and Tea Fungus". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 13 (4): 538–550. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12073.

- ^ a b Jarrell J, Cal T, Bennett JW (2000). "The Kombucha Consortia of yeasts and bacteria". Mycologist. 14 (4). Elsevier: 166–170. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(00)80034-8.

- ^ Jonas, Rainer; Farah, Luiz F. "Production and application of microbial cellulose". Polymer Degradation and Stability. 59 (1–3): 101–106. doi:10.1016/s0141-3910(97)00197-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ernst E (2003). "Kombucha: a systematic review of the clinical evidence". Forschende Komplementärmedizin und klassische Naturheilkunde. 10 (2): 85–87. doi:10.1159/000071667. PMID 12808367.

- ^ Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. "Kombucha". www.mskcc.org. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b "Kombucha Tea". American Cancer Society Complete Guide to Complementary and Alternative Cancer Therapies (2nd ed.). American Cancer Society. 2009. pp. 629–633. ISBN 9780944235713.

Serious side effects and occasional deaths have been associated with drinking Kombucha tea

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hannah Crum; Alex LaGory (2016). The Big Book of Kombucha: Brewing, Flavoring, and Enjoying the Benefits of Fermented Tea. Storey Publishing, LLC. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-61212-433-9.

- ^ a b The Oxford Companion to Sugar and Sweets. Oxford University Press. 1 April 2015. pp. 720–. ISBN 978-0-19-931362-4.

- ^ Troitino, Christina. "Kombucha 101: Demystifying The Past, Present And Future Of The Fermented Tea Drink". Forbes. Retrieved 2017-04-10.

- ^ Dasgupta, Amitava (2011). Effects of Herbal Supplements on Clinical Laboratory Test Results. Berlin, Germany: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 24, 108, 112. ISBN 978-3-1102-4561-5.

- ^ a b Dasgupta, Amitava (2013). "Effects of herbal remedies on clinical laboratory tests". In Dasgupta, Amitava; Sepulveda, Jorge L. (eds.). Accurate Results in the Clinical Laboratory: A Guide to Error Detection and Correction. Amsterdam, NH: Elsevier. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-1241-5783-5.

- ^ Abdualmjid, Reem J; Sergi, Consolato (2013). "Hepatotoxic Botanicals—An Evidence-based Systematic Review". Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 16 (3): 376–404. PMID 24021288.

- ^ Bryant BJ, Knights KM (2011). Chapter 3: Over-the-counter Drugs and Complementary Therapies (3rd ed.). Elsevier Australia. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-7295-3929-6.

Kombucha has been associated with illnesses and death. A tea made from Kombucha is said to be a tonic, but several people have been hospitalised and at least one woman died after taking this product. The cause could not be directly linked to Kombucha, but several theories were offered, e.g. The tea might have reacted with other medications that the woman was taking, or bacteria might grow in the Kombucha liquid and, in patients with suppressed immunity, might prove to be fatal.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Unexplained Severe Illness Possibly Associated with Consumption of Kombucha Tea -- Iowa, 1995 (Report). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Vol. 44. CDC. 8 December 1995. pp. 892–893, 899–900. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Kombucha". Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- ^ Nummer, Brian A. (November 2013). "Kombucha Brewing Under the Food and Drug Administration Model Food Code: Risk Analysis and Processing Guidance". Journal of Environmental Health. 76 (4): 8–11. PMID 24341155.

- ^ a b c d Food Safety Assessment of Kombucha Tea Recipe and Food Safety Plan (PDF) (Report). Food Issue, Notes From the Field. British Columbia (BC) Centre for Disease Control. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ a b "Drug record, Usnic acid (Usnea species)". LiverTox. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 26 July 2017.

- ^ Greenwalt, C. J.; Steinkraus, K. H.; Ledford, R. A. (2000). "Kombucha, the Fermented Tea: Microbiology, Composition, and Claimed Health Effects". Journal of Food Protection. 63 (7): 976–981. doi:10.4315/0362-028X-63.7.976. ISSN 0362-028X. PMID 10914673.

- ^ Grushkin, Daniel (17 February 2015). "Meet the Woman Who Wants to Grow Clothing in a Lab". Popular Science. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Oiljala, Leena (9 September 2014). "BIOCOUTURE Creates Kombucha Mushroom Fabric For Fashion & Architecture". Pratt Institute. Archived from the original on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Hinchliffe, Jessica (25 September 2014). "'Scary and gross': Queensland fashion students grow garments in jars with kombucha". ABCNet.net.au. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Blanc, Phillipe J (February 1996). "Characterization of the tea fungus metabolites". Biotechnology Letters. 18 (2): 139–142. doi:10.1007/BF00128667. Retrieved 17 July 2015.

- ^ Dufresne, C.; Farnworth, E. (2000). "Tea, Kombucha, and health: a review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409–421. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3. ISSN 0963-9969.

- ^ Nguyen, VT; Flanagan, B; Gidley, MJ; Dykes, GA (2008). "Characterization of cellulose production by a gluconacetobacter xylinus strain from kombucha". Current Microbiology. 57 (5): 449–53. doi:10.1007/s00284-008-9228-3. PMID 18704575.

- ^ a b Sreeramulu, G; Zhu, Y; Knol, W (2000). "Kombucha fermentation and its antimicrobial activity". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (6): 2589–94. doi:10.1021/jf991333m. PMID 10888589.

- ^ Teoh, AL; Heard, G; Cox, J (2004). "Yeast ecology of kombucha fermentation". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 95 (2): 119–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2003.12.020. PMID 15282124.

- ^ Dufresne, C; Farnworth, E (2000). "Tea, kombucha, and health: A review". Food Research International. 33 (6): 409–421. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00067-3.

- ^ Velicanski, A; Cvetkovic, D; Markov, S; Tumbas, V; Savatovic, S (2007). "Antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of lemon balm Kombucha". Acta Periodica Technologica (38): 165–72. doi:10.2298/APT0738165V.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ Bauer-Petrovska, B; Petrushevska-Tozi, L (2000). "Mineral and water soluble vitamin content in the kombucha drink". International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 35 (2): 201–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2621.2000.00342.x.

- ^ a b Hamblin, James (8 December 2016). "Is Fermented Tea Making People Feel Enlightened Because of ... Alcohol?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Klaus Kaufmann (1 May 2013). Kombucha Rediscovered!: Revised Edition The Medicinal Benefits of an Ancient Healing Tea. Book Publishing Company. pp. 24–. ISBN 978-0-920470-76-3.

- ^ Sandor Ellix Katz (2012). The Art of Fermentation: An In-depth Exploration of Essential Concepts and Processes from Around the World. Chelsea Green Publishing. pp. 167–. ISBN 978-1-60358-286-5.

- ^ Wyatt, Kristen (12 October 2015). "As kombucha sales boom, makers ask feds for new alcohol test". Associated Press. Retrieved 26 November 2017.

- ^ Algeo, John; Algeo, Adele (1997). "Among the New Words". American Speech. 72 (2): 183–97. doi:10.2307/455789. JSTOR 455789.

- ^ Wong, Crystal (12 July 2007). "U.S. 'kombucha': Smelly and No Kelp". Japan Times. Retrieved 14 June 2015..

- ^ "Kombucha". American Heritage Dictionary (Fifth ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ O'Neill, Molly (28 December 1994). "A Magic Mushroom Or a Toxic Fad?". New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Hesseltine, C. W. (1965). "A Millennium of Fungi, Food, and Fermentation". Mycologia. 57 (2): 149–97. doi:10.2307/3756821. JSTOR 3756821. PMID 14261924.

- ^ Wollan, Malia (24 March 2010). "A Strange Brew May Be a Good Thing". NYTimes. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Rothman, Max (2 May 2013). "'Kombucha Crisis' Fuels Progress". BevNET. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- ^ Crum, Hannah (23 August 2011). "The Kombucha Crisis: One Year Later". BevNET. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Narula, Svati Kirsten (26 March 2015). "The American kombucha craze, in one home-brewed chart". Quartz. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Carr, Coeli (9 August 2014). "Kombucha cha-ching: A probiotic tea fizzes up strong growth". CNBC. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Esterl, Mike (23 November 2016). "Slow Start for Soda Industry's Push to Cut Calories". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 November 2016.