Syrian Kurdistan: Difference between revisions

→Etymology: rmv 1920 map - this map is from somebody's personal website/blog, not an RS |

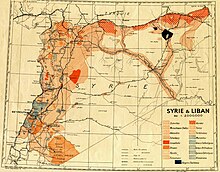

→Etymology: Rmv 1803 Cedid map; it's entirely in Arabic and does not show modern borders; this adds nothing to the English Wikipedia reader's understanding of Syrian Kurdistan, and I question its reliability/accuracy due to its age; old maps are not accurate |

||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

The idea of a Syrian territory being part of a "Kurdistan" or "Syrian Kurdistan" gained more widespread support among Syrian Kurds in the 1980s and 1990s.{{sfn|Tejel|2009|pp=93–95}}<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Khen|first=Hilly Moodrick-Even|url=https://books.google.ch/books?id=mHG9DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA276&dq=syrian+kurdistan+and+kdp-s&hl=de&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjIscX0oYDtAhUNDuwKHbL1B9YQ6AEwAnoECAcQAg#v=onepage&q=syrian%20kurdistan%20and%20kdp-s&f=false|title=The Syrian War: Between Justice and Political Reality|last2=Boms|first2=Nir T.|last3=Ashraph|first3=Sareta|date=2020-01-09|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-108-48780-1|pages=275|language=en}}</ref> Several smaller Kurdish political movements in Syria, amongst them the Yekiti and the Azadi, began to organize manifestations in cities with a large Kurdish population demanding a better treatment of the Kurdish population while advocating for an recognition of a "Syrian Kurdistan".<ref name=":0" /> This development was fueled by the [[Kurdistan Workers' Party]] (PKK) that strengthened Kurdish nationalist ideas in Syria, whereas local Kurdish parties had previously lacked success in promoting "a clear political project" related to a Kurdish identity, partially due to political repression by the Syrian government.{{sfn|Tejel|2009|p=93}} Despite the role of the PKK in initially spreading the concept of "Syrian Kurdistan", the [[Democratic Union Party (Syria)|Democratic Union Party]] (PYD) (the Syrian "successor" of the PKK).{{sfn|Allsopp|van Wilgenburg|2019|p=28}} generally refrained from calling for the establishment of "Syrian Kurdistan".{{sfn|Tejel|2009|p=123}} As the PKK and PYD call for the removal of national borders in general, the two parties believed that there was no need for the creation of a separate "Syrian Kurdistan", as their [[Internationalism (politics)|internationalist]] project would allow for the unification of Kurdistan through indirect means.<ref name="kaya">Kaya, Z. N., & Lowe, R. (2016). [http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64770/1/Kaya%20and%20Lowe.pdf The curious question of the PYD-PKK relationship]. In G. Stansfield, & M. Shareef (Eds.), The Kurdish question revisited (pp. 275–287). London: Hurst.</ref> Some observers see Syrian Kurdistan as a concept emerging from the ongoing Syrian Civil War.<ref>{{Citation|last=Lowe|first=Robert|title=The Emergence of Western Kurdistan and the Future of Syria|date=2014|url=https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137409997_12|work=Conflict, Democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria|pages=225–246|editor-last=Romano|editor-first=David|place=New York|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US|language=en|doi=10.1057/9781137409997_12|isbn=978-1-137-40999-7|access-date=2020-11-10|editor2-last=Gurses|editor2-first=Mehmet}}</ref> |

The idea of a Syrian territory being part of a "Kurdistan" or "Syrian Kurdistan" gained more widespread support among Syrian Kurds in the 1980s and 1990s.{{sfn|Tejel|2009|pp=93–95}}<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|last=Khen|first=Hilly Moodrick-Even|url=https://books.google.ch/books?id=mHG9DwAAQBAJ&pg=PA276&dq=syrian+kurdistan+and+kdp-s&hl=de&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjIscX0oYDtAhUNDuwKHbL1B9YQ6AEwAnoECAcQAg#v=onepage&q=syrian%20kurdistan%20and%20kdp-s&f=false|title=The Syrian War: Between Justice and Political Reality|last2=Boms|first2=Nir T.|last3=Ashraph|first3=Sareta|date=2020-01-09|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-1-108-48780-1|pages=275|language=en}}</ref> Several smaller Kurdish political movements in Syria, amongst them the Yekiti and the Azadi, began to organize manifestations in cities with a large Kurdish population demanding a better treatment of the Kurdish population while advocating for an recognition of a "Syrian Kurdistan".<ref name=":0" /> This development was fueled by the [[Kurdistan Workers' Party]] (PKK) that strengthened Kurdish nationalist ideas in Syria, whereas local Kurdish parties had previously lacked success in promoting "a clear political project" related to a Kurdish identity, partially due to political repression by the Syrian government.{{sfn|Tejel|2009|p=93}} Despite the role of the PKK in initially spreading the concept of "Syrian Kurdistan", the [[Democratic Union Party (Syria)|Democratic Union Party]] (PYD) (the Syrian "successor" of the PKK).{{sfn|Allsopp|van Wilgenburg|2019|p=28}} generally refrained from calling for the establishment of "Syrian Kurdistan".{{sfn|Tejel|2009|p=123}} As the PKK and PYD call for the removal of national borders in general, the two parties believed that there was no need for the creation of a separate "Syrian Kurdistan", as their [[Internationalism (politics)|internationalist]] project would allow for the unification of Kurdistan through indirect means.<ref name="kaya">Kaya, Z. N., & Lowe, R. (2016). [http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/64770/1/Kaya%20and%20Lowe.pdf The curious question of the PYD-PKK relationship]. In G. Stansfield, & M. Shareef (Eds.), The Kurdish question revisited (pp. 275–287). London: Hurst.</ref> Some observers see Syrian Kurdistan as a concept emerging from the ongoing Syrian Civil War.<ref>{{Citation|last=Lowe|first=Robert|title=The Emergence of Western Kurdistan and the Future of Syria|date=2014|url=https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137409997_12|work=Conflict, Democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria|pages=225–246|editor-last=Romano|editor-first=David|place=New York|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan US|language=en|doi=10.1057/9781137409997_12|isbn=978-1-137-40999-7|access-date=2020-11-10|editor2-last=Gurses|editor2-first=Mehmet}}</ref> |

||

The concept of a Syrian Kurdistan gained even more relevance after the [[Syrian Civil War]]'s start, as Kurdish-inhabited areas in northern Syria fell under the control of Kurdish-dominated factions. The PYD established an [[Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria|autonomous administration in northern Syria]] which it eventually began to call "Rojava" or "West Kurdistan".<ref name="kaya" /><ref name="cambridge">[https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/japanese-journal-of-political-science/article/kurdish-regional-selfrule-administration-in-syria-a-new-model-of-statehood-and-its-status-in-international-law-compared-to-the-kurdistan-regional-government-krg-in-iraq/E27336DA905763412D42038E476BBE61/core-reader Kurdish Regional Self-rule Administration in Syria: A new Model of Statehood and its Status in International Law Compared to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq]</ref><ref name="Icarus" /> By 2014, many local Kurds used this name synonymously to northeastern Syria.<ref name="Reuters 2014">{{cite news|date=22 January 2014|title=Special Report: Amid Syria's violence, Kurds carve out autonomy|language=en|work=Reuters|url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-kurdistan-specialreport/special-report-amid-syrias-violence-kurds-carve-out-autonomy-idUSBREA0L17320140122|access-date=1 August 2020}}</ref> Non-PYD parties such as the KNC also began to raise demands for the establishment of Syrian Kurdistan as separate area, raising increasing concerns by Syrian nationalists and some observers who regarded these plans as attempts to divide Syria.<ref name="zamanalwsl" /> As the PYD-led administration gained control over increasingly ethnically diverse areas, however, the use of "Rojava" for the merging [[proto-state]] was gradually reduced in official contexts.{{sfn|Allsopp|van Wilgenburg|2019|pp=89, 151–152}} Regardless, the polity continued to be called Rojava by locals and international observers,<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/10/turkey-military-operation-syria-latest-updates-191013083950643.html |title=Turkey's military operation in Syria: All the latest updates |work=al Jazeera |date=14 October 2019 |access-date=29 October 2019}}</ref><ref name="gurcan">{{cite web|url=https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2019/11/turkey-syria-pkk-worried-by-growing-popularity-of-ypg-kurds.html |title=Is the PKK worried by the YPG's growing popularity? |author=Metin Gurcan |work=[[al-Monitor]]|date=7 November 2019 |access-date=7 November 2019 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url = https://morningstaronline.co.uk/article/f/communist-volunteers-fighting-turkish-invasion-syria| title = The Communist volunteers fighting the Turkish invasion of Syria| date = 31 October 2019| work = [[Morning Star (British newspaper)|Morning Star]]| access-date = 1 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url = https://www.ardmediathek.de/ard/player/Y3JpZDovL25kci5kZS81YmI0NzU0OC0zNGI3LTRlMTYtYWI2MC03YWM3ZDA5YmRhNDQ/| title = Nordsyrien: Warum ein Deutscher sein Leben für die Kurden riskiert | trans-title= Northern Syria: Why a German risks his life for the Kurds |language = de| date = 31 October 2019| work = ARD| access-date = 1 November 2019}}</ref> with journalist Metin Gurcan noting that "the concept of Rojava [had become] a brand gaining global recognition" by 2019.<ref name="gurcan" /> |

|||

== Extent == |

== Extent == |

||

Revision as of 19:11, 2 January 2021

Syrian Kurdistan is a Kurdish-inhabited area in northern Syria surrounding three noncontiguous enclaves along the Turkish and Iraqi borders: Afrin in the northwest, Kobani in the north, and Jazira in the northeast.[1] Syrian Kurdistan is sometimes called Western Kurdistan or Rojava,[a] one of the four "Lesser Kurdistans" that comprise "Greater Kurdistan",[2] alongside Iranian Kurdistan,[b] Turkish Kurdistan,[c] and Iraqi Kurdistan.[d][3]

The term Syrian Kurdistan is often used in the context of Kurdish nationalism, which makes it a controversial concept among proponents of Syrian and Arab nationalism. There is ambiguity about its geographical extent, and the term has different meanings depending on context.

History

Sharafkhan Bidlisi's 1596 epic of Kurdish history from the late 13th century to his own day, the Sharafnama, describes Kurdistan as extending from the Persian Gulf to the Ottoman vilayets of Malatya and Marash (Kahramanmaraş), an wide definition that counts the Lurs as Kurds and which takes an extreme expansionist view of the south. Lying to either side of the Gulf–Anatolia line were the vilayets of Diyarbekir, Mosul, "non-Arab Iraq", "Arab Iraq", Fars, Azerbaijan, Lesser Armenia, and Greater Armenia. Ahmad Khani's 1692 epic Mem û Zîn offers a similar conception of geography. In the 19th century poetry of Haji Qadir Koyi, literary Kurdistan extended across the north of later mandatory Syria, including Nusaybin and Alexandretta (İskenderun) on the Mediterranean Sea's Gulf of Alexandretta.[4] This is the location of the Syrian Gates, the traditional western terminus of Syria, though with the rest of the sanjak of Alexandretta it was eventually incorporated into Turkey as Hatay Province.[citation needed]

At the beginning of the 17th century, land on either side of the Euphrates was settled by Kurds forced to migrate there at the Ottoman Sultans' behest from lands elsewhere within the empire. The area on the river's right bank was the main focus of settlement, especially around Kobanî. In the 18th century, some of the Kurdish tribes of Syria (or Bilad al-Sham) remained closely related to those of neighbouring areas of Kurdistan, but some others were assimilated with local Arab tribes.[4]

At the end of the fighting between the Ottoman Empire during World War I and the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, and the Arab Revolt, the territory of modern-day Syria and Iraq had been occupied by the Allies, and a Kurdish political and territorial entity was proposed. However, since neither Britain nor France was willing to withdraw from occupied areas of the Occupied Enemy Territory Administration, the territory allotted to the Kurds was to be located wholly in areas still under Turkish control at the time of the first partition of the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of Sèvres in August 1920.[5]

At the end of World War I, Kurdish-populated areas of the partitioned Ottoman Empire were divided from one another and from the rest of Kurdistan by the establishment of the border of the French Mandate, which was given authority over three Kurdish-populated areas left on the southern side of the new line, namely the areas of the Kurd Mountains (or Kurd-Dagh), Jarabulus, and the French Mandate territory in Upper Mesopotamia (the Northern Jazira). From the beginning of the Syrian state under the French Mandate, the geographical discontinuity of the Kurdish territory, as well as its relative smallness compared with the Kurdish areas of Iraq and Turkey, shaped much of the region's subsequent history. According to Jordi Tejel, "These three Kurdish enclaves constituted … a natural extension of Kurdish territory into Turkey and Iraq".[4]

In late 1919, the French Armed Forces had arrived in the Kurd Mountains, which they were able to pass through without much difficulty. In the Jazira, French troops were resisted more effectively. By the end of the Franco-Turkish War with the Treaty of Ankara in 1921, which established a provisional border between the new Turkish polity and France's new mandate territories, France and Turkey were cultivating relations with the area's tribes in the hope of establishing territorial claims. French military efforts were hindered by propaganda favouring Turkey distributed among Kurdish and Arab tribes. Resistance to the French in the Jazira continued until 1926. By 1927, the Kurdish-majority villages of the area numbered 47. (The numbers of Kurds and Kurdish villages grew significantly in the Interwar period.)[4]

During the 1920s, use of the Latin alphabet to write the Kurdish languages was introduced by Celadet Bedir Khan and his brother Kamuran Alî Bedirxan and became widespread in Syrian Kurdistan,[dubious ] as it did in Turkish Kurdistan.[6] Early French Syria's Kurds were predominantly speakers of Kurmanji, a northern Kurdish language. Besides the main three Kurdish enclaves, there were other Syrian Kurds outwith Syrian Kurdistan; primarily these were resident in the major cities of Aleppo (like the Alawite Kurds) and Damascus, though Yazidi Kurds inhabited Jabal Sam'an and others were nomads. Just as their districts were fragmented, the Kurdish inhabitants of Syria in the French mandatory period were heterogenous, and refugees arriving from Turkish and Iraqi Kurdistan helped foster Kurdish political consciousness, engendering a "pan-Kurdism" that complemented pre-existing Kurdish identities. The immigration from Kurdish areas outside Syria increased the Kurdish component of the population in Jazira.[4]

By the 1960s, after the eventual settlement of the borders of the successor states after the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire, Kurdistan was frequently divided into four regions[dubious ] corresponding to the Kurdish-majority areas of four adjacent modern states: Iran, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria.[dubious ] Syrian Kurdistan appeared alongside Persian (or Iranian), Iraqi, and Turkish Kurdistan as one of the principal regional divisions of Kurdish-inhabited territory in the Middle East.[7][8][9][10][11][12] Three discontinuous areas Kurdish-inhabited areas on the Syria–Turkey border constitute Syrian Kurdistan, or the Kurdish regions of Syria: the Kurd Mountains (or Kurd-Dagh), the area around Kobanî, and Upper Mesopotamia (Northern Jazira).[13] In these areas were concentrated the roughly half a million Kurds in Syria in the 1970s.[12] At that time, Kurds represented around 10% of Syria's population, living mainly in these "well-defined areas" on the northern border.[13] These areas are adjacent to Turkish Kurdistan to the north and Iraqi Kurdistan to the east.[4]

Etymology

The idea of a Syrian territory being part of a "Kurdistan" or "Syrian Kurdistan" gained more widespread support among Syrian Kurds in the 1980s and 1990s.[14][15] Several smaller Kurdish political movements in Syria, amongst them the Yekiti and the Azadi, began to organize manifestations in cities with a large Kurdish population demanding a better treatment of the Kurdish population while advocating for an recognition of a "Syrian Kurdistan".[15] This development was fueled by the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK) that strengthened Kurdish nationalist ideas in Syria, whereas local Kurdish parties had previously lacked success in promoting "a clear political project" related to a Kurdish identity, partially due to political repression by the Syrian government.[16] Despite the role of the PKK in initially spreading the concept of "Syrian Kurdistan", the Democratic Union Party (PYD) (the Syrian "successor" of the PKK).[17] generally refrained from calling for the establishment of "Syrian Kurdistan".[18] As the PKK and PYD call for the removal of national borders in general, the two parties believed that there was no need for the creation of a separate "Syrian Kurdistan", as their internationalist project would allow for the unification of Kurdistan through indirect means.[19] Some observers see Syrian Kurdistan as a concept emerging from the ongoing Syrian Civil War.[20]

The concept of a Syrian Kurdistan gained even more relevance after the Syrian Civil War's start, as Kurdish-inhabited areas in northern Syria fell under the control of Kurdish-dominated factions. The PYD established an autonomous administration in northern Syria which it eventually began to call "Rojava" or "West Kurdistan".[19][21][22] By 2014, many local Kurds used this name synonymously to northeastern Syria.[23] Non-PYD parties such as the KNC also began to raise demands for the establishment of Syrian Kurdistan as separate area, raising increasing concerns by Syrian nationalists and some observers who regarded these plans as attempts to divide Syria.[24] As the PYD-led administration gained control over increasingly ethnically diverse areas, however, the use of "Rojava" for the merging proto-state was gradually reduced in official contexts.[25] Regardless, the polity continued to be called Rojava by locals and international observers,[26][27][28][29] with journalist Metin Gurcan noting that "the concept of Rojava [had become] a brand gaining global recognition" by 2019.[27]

Extent

"Syrian Kurdistan", as understood in the modern sense, has no clearly defined territory.[30] According to the Crisis Group, the term "refers to the western area of 'Kurdistan'", namely those in Syria.[22] Although the concept of an independent Kurdistan as homeland of the Kurdish people has a long history,[31] the extent of said territory has been disputed over time.[30] Kurds have lived in territories which later became part of modern Syria for centuries,[32][33] and following the partition of the Ottoman Empire, the Kurdish population before living in the Ottoman Empire, was divided between its successor states Turkey, Iraq and Syria.[34] Local Kurdish parties generally maintained ideologies which stayed in a firmly Syrian framework, and did not aspire to create a separate Syrian Kurdistan.[35] In the 1920s, there were two separate demands for an autonomy of the areas with a Kurdish majority. One of Nouri Kandy, an influential Kurd from the Kurd Dagh, and another one of the Kurdish tribal leaders of the Barazi confederation. Both demands were not taken into consideration by the authorities of the French Mandate.[36] According to Tejel, until the 1980s Kurdish-inhabited areas of Syria were mainly regarded as "Kurdish regions of Syria".[30]

In the 20th century, Kurdistan was usually only included areas in Turkey and Iraq. The Kurdish-inhabited areas in northern Syria are adjacent to "Turkish Kurdistan" in the north and "Iraqi Kurdistan" in the east.[37]

By 2013, "Rojava" had become synonymous with PYD-ruled areas, regardless of ethnic majorities. For the most part, the term was used to refer to the "non-contiguous Kurdish-populated areas" in the region.[22] In 2015 a map by Kurdish National Council (KNC) member Nori Brimo was published which largely mirrored the Ekurd Daily's maps, but also included the Hatay Province. The claimed map includes large swaths of Arab-majority areas.[24]

Climate and agriculture

The lowlands of Syrian Kurdistan is productive arable farmland, giving the region the appellation of the "granary" of Syria.[38] Similarly, the adjacent Iraqi Kurdistan is known as the granary of Iraq.[38]

Demographic background

Northern Syria is an ethnically diverse region. Kurds constitute one of several groups which have lived in northern Syria since antiquity or the Middle Ages.[39][32][e] The first Kurdish communities constituted a minority and mostly consisted of nomads or military colonists.[33][32] During the Ottoman Empire (1516–1922), large Kurdish-speaking tribal groups both settled in and were deported to areas of northern Syria from Anatolia.[18] The last years of Ottoman rule witnessed extensive demographic changes in northern Syria as a result of the Assyrian Genocide and mass migrations.[40] Many Assyrians fled to Syria during the genocide and settled mainly in the Jazira area.[41]

Starting in 1926, the region saw another immigration of Kurds following the failure of the Sheikh Said rebellion against the Turkish authorities.[42] Waves of Kurds fled their homes in Turkey and settled in Syrian Al-Jazira Province, where they were granted citizenship by the authorities of the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon.[43] The number of Kurds settled in the Jazira province during the 1920s was estimated at 20,000[44] to 25,000 people,[45] out of 100,000 inhabitants, with the remainder of the population being Christians (Syriac, Armenian, Assyrian) and Arabs.[44] According to Michael Gunter, many Kurds still do not see themselves as belonging to either the Turkish or Syrian Kurdistan, but rather as one who originates from "above the line" (Kurdish: Ser Xhet) or "below the line" (Kurdish:Bin Xhet).[46]

French mandate authorities gave the new Kurdish refugees considerable rights and encouraged minority autonomy as part of a divide and rule strategy and recruited heavily from the Kurds and other minority groups, such as Alawite and Druze, for its local armed forces.[47] French Mandate authorities encouraged their immigration and granted them Syrian citizenship.[48] Giving Syrian nationality to refugees by French mandate authorities was legally required so that refugees could be hired as employees of the Syrian state (Armenians as clerks and interpreters and Kurds as gendarmes) but also to receive grants of state land by mandate authorities.[49]

The French official reports show the existence of at most 45 Kurdish villages in Jazira prior to 1927. A new wave of refugees arrived in 1929.[50] The mandatory authorities continued to encourage Kurdish immigration into Syria, and by 1939, the villages numbered between 700 and 800 [50] due to several successive Kurdish immigration waves from Turkey.[49] The French authorities themselves generally organized the settlement of the refugees. One of the most important of these plans was carried out in Upper Jazira in northeastern Syria where the French built new towns and villages (such as Qamishli) were built with the intention of housing the refugees considered to be "friendly". This has encouraged the non-Turkish minorities that were under Turkish pressure to leave their ancestral homes and property, they could find refuge and rebuild their lives in relative safety in neighboring Syria.[51]

These successive Kurdish immigrations from Turkey have led the governing Ba'ath Party to think about Arabization policies in northern Syria, settling 4000 farmer families from areas inundated by the Tabqa Dam in Raqqa Governorate in al-Hasakah Governorate [52] Mass migration also took place during the Syrian civil war. Accordingly, estimates as to the ethnic composition of northern Syria vary widely, ranging from claims about a Kurdish majority to claims about Kurds being a small minority.[53] In addition, the Kurdish population of Syria has been highly segmented due to the different backgrounds and lifestyles of Kurdish groups.[54]

See also

Notes

- ^ Kurdish: Rojavayê Kurdistanê, lit. 'Kurdistan where the sun sets'

- ^ Kurdish: Rojhilatê Kurdistanê, lit. 'Kurdistan where the sun rises'

- ^ Kurdish: Bakurê Kurdistanê, lit. 'Northern Kurdistan'

- ^ Kurdish: Başûrê Kurdistanê, lit. 'Southern Kurdistan'

- ^ It is difficult to properly define early Kurds, as "Kurdish" was often used as a catch-all word for nomadic tribal groups west of Iran during antiquity and medieval times.[32]

References

- ^ Kajjo 2020, p. 284; Lange 2018, p. 285; O'Leary 2018; Phillips 2017, p. 67; Gunter 2014, p. 8.

- ^ Bengio, Ofra (2014). Kurdish Awakening: Nation Building in a Fragmented Homeland. University of Texas Press. p. 2.

Hence the terms: rojhalat (east, Iran), bashur (south, Iraq), bakur (north, Turkey), and rojava (west, Syria).

- ^ Kajjo 2020, p. 273; O'Leary 2018; Bengio 2017, p. 79.

- ^ a b c d e f Tejel 2020.

- ^ Bulloch, John; Morris, Harvey (1992). No Friends But the Mountains: The Tragic History of the Kurds. Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-508075-9.

The British and the French made it clear from the outset that they were unwilling to surrender those parts of Iraqi and Syrian Kurdistan which fell under their control, and that an independent Kurdistan, if such an entity were to be created, would have to be in what was still Turkish territory.

- ^ Berberoglu, Berch (1999). Turmoil in the Middle East: Imperialism, War, and Political Instability. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-4412-2.

Then, in the 1920s, the Bedirkhan brothers introduced the Latin alphabet, which became standard in Turkish and Syrian Kurdistan.

- ^ Ghassemlou, Abdul Rahman (1965). Kurdistan and the Kurds. Publishing House of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. p. 21.

(i.e. the present-day Turkish, Iraqi and Syrian Kurdistan)

- ^ In the Dispersion. Jersualem: World Zionist Organization, Organization Department, Research Section. 1962. p. 147.

This book tells the tale of the Kurdish Jews who lived in the one hundred and ninety towns in what is now Iraqi, Persian, Turkish and Syrian Kurdistan

- ^ Gotlieb, Yosef (1995). Development, Environment, and Global Dysfunction: Toward Sustainable Recovery. Delray Beach, FL: St Lucie Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-57444-012-6.

The situation in Turkish Kurdistan is consistent with that of Iranian, Iraqi, and Syrian Kurdistan.

- ^ Mirawdeli, Kamal M. (1993). Kurdistan: Toward a Cultural-historical Definition. Badlisy Center for Kurdish Studies. p. 4.

Turkish Kurdistan, an Iraqi Kurdistan, an Iranian Kurdistan, and a Syrian Kurdistan

- ^ Gotlieb, Yosef (1982). Self-determination in the Middle East. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-03-062408-7.

While the Kurds in Turkish, Soviet, Syrian, and Persian Kurdistan were held in place with and iron fist, the Iraqi Kurds fought virtually alone throughout the 1960s.

- ^ a b Bruinessen, Martin van (1978). Agha, Shaikh and State: On the Social and Political Organization of Kurdistan. University of Utrecht. p. 22.

I shall refer to these parts as Turkish, Persian, Iraqi, and Syrian Kurdistan. ... Most sources agree that there are approximately half a million Kurds in Syria.

- ^ a b Chaliand, Gérard, ed. (1993) [1978]. Les Kurdes et le Kurdistan [A People Without a Country: The Kurds and Kurdistan]. Translated by Pallis, Michael. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-194-5.

Are these three regions - Kurd-Dagh, Ain-Arab, and Northern Jezireh - part of Kurdistan? Do they form a Syrian Kurdistan, or are they merely region of Syria which happen to be populated with Kurds? The important thing is that 10% of Syria's population are Kurds who live in their own way in well-defined areas in the north of the country. Syrian Kurdistan has thus become a broken up territory and we would do better to talk about the Kurdish regions of Syria. What matters is that these people are being denied their legitimate right to have their own national and cultural identity.

- ^ Tejel 2009, pp. 93–95.

- ^ a b Khen, Hilly Moodrick-Even; Boms, Nir T.; Ashraph, Sareta (2020-01-09). The Syrian War: Between Justice and Political Reality. Cambridge University Press. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-108-48780-1.

- ^ Tejel 2009, p. 93.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg 2019, p. 28.

- ^ a b Tejel 2009, p. 123.

- ^ a b Kaya, Z. N., & Lowe, R. (2016). The curious question of the PYD-PKK relationship. In G. Stansfield, & M. Shareef (Eds.), The Kurdish question revisited (pp. 275–287). London: Hurst.

- ^ Lowe, Robert (2014), Romano, David; Gurses, Mehmet (eds.), "The Emergence of Western Kurdistan and the Future of Syria", Conflict, Democratization, and the Kurds in the Middle East: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Syria, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 225–246, doi:10.1057/9781137409997_12, ISBN 978-1-137-40999-7, retrieved 2020-11-10

- ^ Kurdish Regional Self-rule Administration in Syria: A new Model of Statehood and its Status in International Law Compared to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq

- ^ a b c "Flight of Icarus? The PYD's Precarious Rise in Syria" (PDF). International Crisis Group: Middle East Report N°151. 8 May 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

: "The Middle East's present-day borders stem largely from the 1916 Sykes-Picot agreement between France and the UK. Deprived of a state of their own, Kurds found themselves living in four different countries, Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran. The term 'rojava' ('west' in Kurdish) refers to the western area of 'Kurdistan'; today in practice it includes non-contiguous Kurdish-populated areas of northern Syria where the PYD proclaimed a transitional administration in November 2013.".

- ^ "Special Report: Amid Syria's violence, Kurds carve out autonomy". Reuters. 22 January 2014. Retrieved 1 August 2020.

- ^ a b Mohamed Al Hussein (21 February 2020). "Map of proposed Syrian Kurdistan provoke questions". zamanalwsl. Retrieved 12 September 2020.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg 2019, pp. 89, 151–152.

- ^ "Turkey's military operation in Syria: All the latest updates". al Jazeera. 14 October 2019. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- ^ a b Metin Gurcan (7 November 2019). "Is the PKK worried by the YPG's growing popularity?". al-Monitor. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- ^ "The Communist volunteers fighting the Turkish invasion of Syria". Morning Star. 31 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ "Nordsyrien: Warum ein Deutscher sein Leben für die Kurden riskiert" [Northern Syria: Why a German risks his life for the Kurds]. ARD (in German). 31 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ^ a b c Tejel 2009, p. 95.

- ^ Tejel 2009, p. 69.

- ^ a b c d Meri 2006, p. 445.

- ^ a b Vanly 1992, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Gunter 2016, p. 87.

- ^ Tejel 2009, p. 86.

- ^ Tejel 2009, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Gunter 2016, p. 88.

- ^ a b Bruinessen, Martin Van (1992). Agha, Shaikh, and State: The Social and Political Structures of Kurdistan. London: Zed Books. ISBN 978-1-85649-018-4.

The plains of Iraqi and Syrian Kurdistan are the granaries of Iraq and Syria, respectively.

- ^ Vanly 1992, p. 116: "To the east of Kurd-Dagh and separated from it by the Afrin valley lies the western and mountainous part of the Syrian district of Azaz which is also inhabited by Kurds, and a Kurdish minority lives in the northern counties of Idlib and Jerablos. There is reason to believe that the establishment of Kurds in these areas, a defensive site commanding the path to Antioch, goes back to the Seleucid era."

- ^ Tejel 2009, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Bat Yeʼor (2002). Islam and Dhimmitude: Where Civilizations Collide. p. 162. ISBN 9780838639429.

- ^ Abu Fakhr, Saqr, 2013. As-Safir daily Newspaper, Beirut. in Arabic Christian Decline in the Middle East: A Historical View

- ^ Dawn Chatty (2010). Displacement and Dispossession in the Modern Middle East. Cambridge University Press. pp. 230–232. ISBN 978-1-139-48693-4.

- ^ a b Simpson, John Hope (1939). The Refugee Problem: Report of a Survey (First ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 458. ASIN B0006AOLOA.

- ^ McDowell, David (2005). A Modern History of the Kurds (3. revised and upd. ed., repr. ed.). London [u.a.]: Tauris. p. 469. ISBN 1-85043-416-6.

- ^ Gunter 2016, p. 90.

- ^ Yildiz, Kerim (2005). The Kurds in Syria : the forgotten people (1. publ. ed.). London [etc.]: Pluto Press, in association with Kurdish Human Rights Project. p. 25. ISBN 0745324991.

- ^ Kreyenbroek, Philip G.; Sperl, Stefan (1992). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. London: Routledge. pp. 147. ISBN 0-415-07265-4.

- ^ a b White, Benjamin Thomas (2017). "Refugees and the definition of Syria, 1920–1939*". Past and Present (235): 168. Retrieved 2021-01-01.

- ^ a b Tejel 2009, p. 144.

- ^ Tachjian Vahé, The expulsion of non-Turkish ethnic and religious groups from Turkey to Syria during the 1920s and early 1930s, Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence, [online], published on: 5 March 2009, accessed 09/12/2019, ISSN 1961-9898

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg 2019, p. 27.

- ^ Allsopp & van Wilgenburg 2019, pp. 7–16.

- ^ Tejel 2009, p. 9.

Works cited

- Allsopp, Harriet; van Wilgenburg, Wladimir (2019). The Kurds of Northern Syria. Volume 2: Governance, Diversity and Conflicts. London; New York City; etc.: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-8386-0445-5.

- Bengio, Ofra (2017). "Separated but Connected: The Synergic Effects in the Kurdistan Sub-System". In Stansfield, Gareth; Shareef, Mohammed (eds.). The Kurdish Question Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 77–92. ISBN 978-0-19-068718-2. OCLC 966557019.

- Gunter, Michael M. (2014). Out of Nowhere: The Kurds of Syria in Peace and War. C. Hurst & Co. ISBN 978-1-84904-435-6. OCLC 894764541.

- ———————— (2016). The Kurds: A Modern History (1st ed.). Markus Wiener Publishers. ISBN 978-1-558766150. OCLC 938347895.

- Kajjo, Sirwan (2020). "Syrian Kurds: Rising from the Ashes of Persecution". In Khen, Hilly Moodrick-Even; Boms, Nir T.; Ashraph, Sareta (eds.). The Syrian War: Between Justice and Political Reality. Cambridge University Press. pp. 268–286. ISBN 978-1-108-48780-1. OCLC 1122689764.

- Lange, Katharina (2018). "Syria". In Maisel, Sebastian (ed.). The Kurds: An Encyclopedia of Life, Culture, and Society. ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-1-4408-4257-3. OCLC 1031040153.

- Meri, Josef W. (2006). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Volume 1: A - K. New York City, London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

- O'Leary, Brendan (January 2018). "The Kurds, the Four Wolves, and the Great Powers" (PDF). The Journal of Politics. 80 (1): 353–366. doi:10.1086/695343. ISSN 0022-3816.

- Phillips, David L. (2017) [2015]. The Kurdish Spring: A New Map of the Middle East. Routledge. ISBN 9781351480376. OCLC 1001946833.

- Tejel, Jordi (2009). Syria's Kurds: History, Politics and Society. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-42440-0.

- Tejel, Jordi (2020). "The Complex and Dynamic Relationship of Syria's Kurds with Syrian Borders: Continuities and Changes". In Cimino, Matthieu (ed.). Syria: Borders, Boundaries, and the State. Mobility & Politics. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 243–267. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-44877-6_11. ISBN 978-3-030-44877-6. OCLC 1159172679.

- Vanly, Ismet Chériff (1992). "The Kurds in Syria and Lebanon". In Philip G. Kreyenbroek; Stefan Sperl (eds.). The Kurds: A Contemporary Overview. New York City, London: Routledge. pp. 112–134. ISBN 978-0-415-96691-7.

External links

- Syria (Rojava or Western Kurdistan) by The Kurdish Project

- Examining the Experiment in Western Kurdistan by the LSE Middle East Centre

- The Emergence of Western Kurdistan and the Future of Syria by Robert Lowe