First Balkan War

| First Balkan War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Balkan Wars | |||||||||

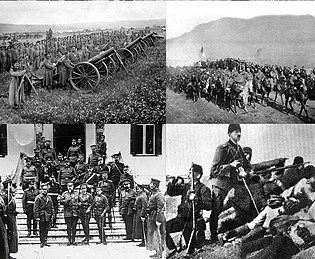

Clockwise from top right: Serbian forces entering the town of Mitrovica; Ottoman troops at the Battle of Kumanovo; Meeting of the Greek king George I and the Bulgarian tsar Ferdinand I in Thessaloniki; Bulgarian heavy artillery | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Balkan League: |

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

436,742 men initially (significantly more than the Balkan League by the end)[5] Circassian volunteers[6][7][8][9] | |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

156,139 killed, wounded or died of disease |

340,000 killed, wounded, captured or died of disease | ||||||||

The First Balkan War (Serbian: Први балкански рат, Prvi balkanski rat; Template:Lang-bg; Greek: Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; Turkish: Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and involved actions of the Balkan League (the Kingdoms of Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece and Montenegro) against the Ottoman Empire. The Balkan states' combined armies overcame the initially numerically inferior (significantly superior by the end of the conflict) and strategically disadvantaged Ottoman armies, achieving rapid success.

The war was a comprehensive and unmitigated disaster for the Ottomans, who lost 83% of their European territories and 69% of their European population.[15] As a result of the war, the League captured and partitioned almost all of the Ottoman Empire's remaining territories in Europe. Ensuing events also led to the creation of an independent Albania, which angered the Serbs. Bulgaria, meanwhile, was dissatisfied over the division of the spoils in Macedonia, and attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 June 1913 which provoked the start of the Second Balkan War.

Background

Tensions among the Balkan states over their rival aspirations to the provinces of Ottoman-controlled Rumelia (Eastern Rumelia, Thrace and Macedonia) subsided somewhat after the mid-19th-century intervention by the Great Powers, which aimed to secure both a more complete protection for the provinces' Christian majority as well as to maintain the status quo. By 1867, Serbia and Montenegro had both secured their independence, which was confirmed by the Treaty of Berlin (1878). The question of the viability of Ottoman rule was revived after the Young Turk Revolution in July 1908, which compelled the Ottoman Sultan to restore the suspended constitution of the empire.

Serbia's aspirations to take over Bosnia and Herzegovina were thwarted by the Bosnian crisis, which led to the Austrian annexation of the province in October 1908. The Serbs then directed their war efforts to the south. After the annexation, the Young Turks tried to induce the Muslim population of Bosnia to emigrate to the Ottoman Empire. Those who took up the offer were resettled by the Ottoman authorities in districts of northern Macedonia with few Muslims. The experiment proved to be a catastrophe since the immigrants readily united with the existing population of Albanian Muslims and participated in the series of 1911 Albanian uprisings and the Albanian revolt of 1912. Some Albanian government troops switched sides.

In May 1912, Albanian rebels seeking national autonomy and the re-installment of Sultan Abdul Hamid II to power, drove the Young Turkish forces out of Skopje and pressed south towards Manastir (now Bitola), forcing the Young Turks to grant effective autonomy over large regions in June 1912.[16][17] Serbia, which had helped the arming of Albanian Catholic and Hamidian rebels and sent secret agents to some of the prominent leaders, took the revolt as a pretext for war.[18] Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria had all been in talks about possible offensives against the Ottoman Empire before the 1912 Albanian revolt had broken out, and a formal agreement between Serbia and Montenegro had been signed on 7 March.[19] On 18 October 1912, King Peter I of Serbia issued a declaration, 'To the Serbian People', which appeared to support Albanians as well as Serbs:

The Turkish governments showed no interest in their duties towards their citizens and turned a deaf ear to all complaints and suggestions. Things got so far out of hand that no one was satisfied with the situation in Turkey in Europe. It became unbearable for the Serbs, the Greeks and for the Albanians, too. By the grace of God, I have therefore ordered my brave army to join in the Holy War to free our brethren and to wish a better future. In Old Serbia, my army will meet not only upon Christian Serbs, but also upon Muslim Serbs, who are equally dear to us, and in addition to them, upon Christian and Muslim Albanians with whom our people have shared joy and sorrow for thirteen centuries now. To all of them we bring freedom, brotherhood and equality.

In a search for allies, Serbia was ready to negotiate a treaty with Bulgaria.[20] The agreement provided that in the event of victory against the Ottomans, Bulgaria would receive all of Macedonia south of the Kriva Palanka–Ohrid line. Serbia's expansion was accepted by Bulgaria as being to the north of the Shar Mountains (Kosovo). The intervening area was agreed to be "disputed" and would be arbitrated by the Tsar of Russia in the event of a successful war against the Ottoman Empire.[21] During the course of the war, it became apparent that the Albanians did not consider Serbia as a liberator, as had been suggested by King Peter I, and the Serbian forces failed to observe his declaration of amity toward Albanians.

After the successful coup d'état for unification with Eastern Rumelia,[22] Bulgaria began to dream that its national unification would be realized. For that purpose, it developed a large army and identified as the "Prussia of the Balkans".[23] However, Bulgaria could not win a war alone against the Ottomans.

In Greece, Hellenic Army officers had rebelled in the Goudi coup of August 1909 and secured the appointment of a progressive government under Eleftherios Venizelos, which they hoped would resolve the Crete question in Greece's favor. They also wanted to reverse their defeat in the Greco-Turkish War (1897) by the Ottomans. An emergency military reorganization, led by a French military mission, had been started for that purpose, but its work was interrupted by the outbreak of war in the Balkans. In the discussions that led Greece to join the Balkan League, Bulgaria refused to commit to any agreement on the distribution of territorial gains, unlike its deal with Serbia over Macedonia. Bulgaria's diplomatic policy was to push Serbia into an agreement that limited its access to Macedonia[24] but, at the same time, to refuse any such agreement with Greece. Bulgaria believed that its army would be able to occupy the larger part of Aegean Macedonia and the important port city of Salonica (Thessaloniki) before the Greeks could do so.

In 1911, Italy had launched an invasion of Tripolitania, now in Libya, which was quickly followed by the occupation of the Dodecanese Islands in the Aegean Sea. The Italians' decisive military victories over the Ottoman Empire and the successful 1912 Albanian revolt encouraged the Balkan states to imagine that they might win a war against the Ottomans. By the spring and the summer of 1912, the various Christian Balkan nations had created a network of military alliances, which became known as the Balkan League.

The Great Powers, most notably France and Austria-Hungary, reacted to the formation of the alliances by trying unsuccessfully to dissuade the Balkan League from going to war. In late September, both the League and the Ottoman Empire mobilized their armies. Montenegro was the first to declare war, on 25 September (O.S.)/8 October. After issuing an impossible ultimatum to the Ottoman Porte on 13 October, Bulgaria, Serbia and Greece declared war on the Ottomans on 17 October (1912). The declarations of war attracted a large number of war correspondents. An estimated 200 to 300 journalists from around the world covered the war in the Balkans in November 1912.[25]

Order of battle and plans

When the war broke out, the Ottoman order of battle had a total of 12,024 officers, 324,718 other ranks, 47,960 animals, 2,318 artillery pieces and 388 machine guns. A total of 920 officers and 42,607 men of them had been assigned in non-divisional units and services, the remaining 293,206 officers and men being assigned into four armies.[26]

Opposing them and continuing their secret prewar settlements for expansion, the three Slavic allies (Bulgarian, Serbs and Montenegrins) had extensive plans to co-ordinate their war efforts: the Serbs and the Montenegrins in the theatre of Sandžak and the Bulgarians and the Serbs in the Macedonian and the Bulgarians alone in the Thracian theater.

The bulk of the Bulgarian forces (346,182 men) was to attack Thrace and to be pitted against the Thracian Ottoman Army of 96,273 men and about 26,000 garrison troops,[27] or about 115,000 in total, according to Hall's, Erickson's and the Turkish General Staff's 1993 studies. The remaining Ottoman army of about 200,000[28] was in Macedonia, to be pitted against the Serbian (234,000 Serbs and 48,000 Bulgarians under Serbian command) and Greek (115,000 men) armies. It was divided into the Vardar and Macedonian Ottoman armies, with independent static guards around the fortress cities of Ioannina (against the Greeks in Epirus) and Shkodër (against the Montenegrins in northern Albania).

Bulgaria

Bulgaria was militarily the most powerful of the four Balkan states, with a large, well-trained and well-equipped army.[1] Bulgaria mobilized a total of 599,878 men out of a population of 4.3 million.[2] The Bulgarian field army counted for nine infantry divisions, one cavalry division and 1,116 artillery units.[1] The commander-in-chief was Tsar Ferdinand, and the operating command was in the hands of his deputy, General Mihail Savov. The Bulgarians also had a small navy of six torpedo boats, which were restricted to operations along the country's Black Sea coast.[29]

Bulgaria was focused on actions in Thrace and Macedonia. It deployed its main force in Thrace by forming three armies. The First Army (79,370 men), under General Vasil Kutinchev, had three infantry divisions and was deployed to the south of Yambol and assigned operations along the Tundzha River. The Second Army (122,748 men), under General Nikola Ivanov, with two infantry divisions and one infantry brigade, was deployed west of the First Army and was assigned to capture the strong fortress of Adrianople (Edirne). Plans had the Third Army (94,884 men), under General Radko Dimitriev, to be deployed east of and behind the First Army and to be covered by the cavalry division that hid it from the Ottomans' sight. The Third Army had three infantry divisions and was assigned to cross Mount Stranja and to take the fortress of Kirk Kilisse (Kırklareli). The 2nd (49,180) and 7th (48,523 men) Divisions were assigned independent roles, operating in Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia, respectively.

Serbia

Serbia called upon about 255,000 men, out of a population of 2,912,000, with about 228 heavy guns, grouped in ten infantry divisions, two independent brigades and a cavalry division, under the effective command of the former war minister, Radomir Putnik.[2] The Serbian High Command, in its prewar war games,[clarification needed] had concluded that the most likely site for the decisive battle against the Ottoman Vardar Army would be on the Ovče Pole Plateau, ahead of Skopje. Thus, the main forces were formed in three armies for the advance towards Skopje and a division and an independent brigade were to co-operate with the Montenegrins in the Sanjak of Novi Pazar.

The First Army (132,000 men), the strongest, was commanded by Crown Prince Alexander and Chief of Staff was Colonel Petar Bojović. The First Army formed the centre of the drive towards Skopje. The Second Army (74,000 men) was commanded by General Stepa Stepanović and had one Serbian and one Bulgarian (7th Rila) division. It formed the army's left wing and advanced towards Stracin. The inclusion of a Bulgarian division was according to a prewar arrangement between Serbian and Bulgarian armies, but the division ceased to obey the orders of Stepanović as soon as the war began but followed only the orders of the Bulgarian High Command. The Third Army (76,000 men) was commanded by General Božidar Janković, and since it was on the right wing, had the task to invade Kosovo and then move south to join the other armies in the expected battle at Ovče Polje. There were two other concentrations in northwestern Serbia across the borders between Serbia and Austria-Hungary: the Ibar Army (25,000 men), under General Mihailo Živković, and the Javor Brigade (12,000 men), under Lieutenant-Colonel Milovoje Anđelković.

Greece

Greece, whose population was then 2,666,000,[3] was considered the weakest of the three main allies since it fielded the smallest army and had suffered a defeat against the Ottomans 16 years earlier, in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897. A British consular dispatch from 1910 expressed the common perception of the Greek army's abilities: "if there is war we shall probably see that the only thing Greek officers can do besides talking is to run away".[30] However, Greece was the only Balkan country to possess a substantial navy, which was vital to the League to prevent Ottoman reinforcements from being rapidly transferred by ship from Asia to Europe. That was readily appreciated by the Serbs and the Bulgarians and was the chief factor in initiating the process of Greece's inclusion in the League.[31] As the Greek ambassador to Sofia put it during the negotiations that led to Greece's entry into the League, "Greece can provide 600,000 men for the war effort. 200,000 men in the field, and the fleet will be able to stop 400,000 men being landed by Turkey between Salonica and Gallipoli."[29]

The Greek army was still undergoing reorganisation by a French military mission, which arrived in early 1911. Under French supervision, the Greeks had adopted the triangular infantry division as their main formation, but more importantly, the overhaul of the mobilization system allowed the country to field and equip a far greater number of troops than had been the case in 1897. Foreign observers estimated Greece would mobilize a force of approximately 50,000 men, but the Greek army fielded 125,000, with another 140,000 in the National Guard and reserves.[3][30] Upon mobilisation, as in 1897, the force was grouped in two field armies, reflecting the geographic division between the two operational theatres that were open to the Greeks: Thessaly and Epirus. The Army of Thessaly (Στρατιά Θεσσαλίας) was placed under Crown Prince Constantine, with Lieutenant-General Panagiotis Danglis as his chief of staff. It fielded the bulk of the Greek forces: seven infantry divisions, a cavalry regiment and four independent Evzones light mountain infantry battalions, roughly 100,000 men. It was expected to overcome the fortified Ottoman border positions and advance towards southern and central Macedonia, aiming to take Thessaloniki and Bitola. The remaining 10,000 to 13,000 men in eight battalions were assigned to the Army of Epirus (Στρατιά Ηπείρου) under Lieutenant-General Konstantinos Sapountzakis. As it had no hope of capturing Ioannina, the heavily fortified capital of Epirus, the initial mission was to pin down the Ottoman forces there until sufficient reinforcements could be sent from the Army of Thessaly after the successful conclusion of operations.

The Greek navy was relatively modern, strengthened by the recent purchase of numerous new units and undergoing reforms under the supervision of a British mission. Invited by Greek Prime Minister Venizelos in 1910, the mission began its work upon its arrival in May 1911. Granted extraordinary powers and led by Vice Admiral Lionel Grant Tufnell, it thoroughly reorganized the Navy Ministry and dramatically improved the number and the quality of exercises in gunnery and fleet maneuvers.[32] In 1912, the core unit of the fleet was the fast armoured cruiser Georgios Averof, which had been completed in 1910 and then was the fastest and the most modern warship in the combatant navies.[33] It was complemented by three rather-antiquated battleships of the Hydra class. There were also eight destroyers, built in 1906–1907, and six new destroyers, hastily bought in summer 1912 as the imminence of war became apparent.[32]

Nevertheless, at the outbreak of the war, the Greek fleet was far from ready. The Ottoman battlefleet retained a clear advantage in number of ships, speed of the main surface units and, most importantly, number and caliber of the ships' guns.[34] In addition, as the war caught the fleet in the middle of its expansion and reorganization, a full third of the fleet (the six new destroyers and the submarine Delfin) reached Greece only after hostilities had started, forcing the navy to reshuffle crews, who consequently suffered from lacking familiarity and training. Coal stockpiles and other war stores were also in short supply, and the Georgios Averof had arrived with barely any ammunition and remained so until late November.[35]

Montenegro

Montenegro was the smallest nation in the Balkan Peninsula, but in recent years before the war, with support from Russia, it had improved its military skills. Also, it was the only Balkan country never to be fully conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Montenegro being the smallest member of the League, did not have much influence. However, it was advantageous for Montenegro,[clarification needed] since when the Ottoman Empire was trying to counter the actions of Serbia, Bulgaria and Greece, there was enough time for Montenegro to prepare, which helped its successful military campaign.

Ottoman Empire

In 1912, the Ottomans were in a difficult position. They had a large population, 26 million, but just over 6.1 million of them lived in its European part, only 2.3 million being Muslims. The rest were Christians, who were considered unfit for conscription. The very poor transport network, especially in the Asian part, dictated that the only reliable way for a mass transfer of troops to the European theatre was by sea, but that faced the risk of the Greek fleet in the Aegean Sea. In addition, the Ottomans were still engaged in a protracted war against Italy in Libya (and by now in the Dodecanese islands of the Aegean), which had dominated the Ottoman military effort for over a year. The conflict lasted until 15 October, a few days after the outbreak of hostilities in the Balkans. The Ottomans were unable to reinforce their positions in the Balkans significantly as their relations with the Balkan states deteriorated over the course of the year.[36]

Forces in Balkans

The Ottomans' military capabilities were hampered by a number of factors, such as domestic strife, caused by the Young Turk Revolution and the counterrevolutionary coup several months later. That resulted in different groups competing for influence within the military. A German mission had tried to reorganize the army, but its recommendations had not been fully implemented. The Ottoman army was caught in the middle of reform and reorganisation. Also, several of the army's best battalions had been transferred to Yemen to face the ongoing rebellion there. In the summer of 1912, the Ottoman High Command made the disastrous decision to dismiss some 70,000 mobilised troops.[2][37] The regular army (Nizam) was well-equipped and had trained active divisions, but the reserve units (Redif) that reinforced it were ill-equipped, especially in artillery, and badly-trained.

The Ottomans' strategic situation was difficult, as their borders were almost impossible to defend against a coordinated attack by the Balkan states. The Ottoman leadership decided to defend all of their territory. As a result, the available forces, which could not be easily reinforced from Asia because of Greek control of the sea and the inadequacy of the Ottoman railway system, were dispersed too thinly across the region. They failed to stand up to the rapidly-mobilized Balkan armies.[38] The Ottomans had three armies in Europe (the Macedonian, Vardar and Thracian Armies), with 1,203 pieces of mobile and 1,115 fixed artillery on fortified areas. The Ottoman High Command repeated its error of previous wars by ignoring the established command structure to create new superior commands, the Eastern Army and Western Army, reflecting the division of the operational theatre between the Thracian (against the Bulgarians) and Macedonian (against the Greeks, Serbs and Montenegrins) fronts.[39]

The Western Army fielded at least 200,000 men,[28] and the Eastern Army fielded 115,000 men against the Bulgarians.[40] The Eastern Army was commanded by Nazim Pasha and had seven corps of 11 regular infantry divisions, 13 Redif divisions[clarification needed] and at least one cavalry divisions:

- I Corps with three divisions (2nd Infantry (minus regiment), 3rd Infantry and 1st Provisional divisions).

- II Corps with three divisions (4th (minus regiment) and 5th Infantry and Uşak Redif divisions).

- III Corps with four divisions (7th, 8th and 9th Infantry Divisions, all minus a regiment, and the Afyonkarahisar Redif Division).

- IV Corps with three divisions (12th Infantry Division (minus regiment), İzmit and Bursa Redif divisions).

- XVII Corps with three divisions (Samsun, Ereğli and İzmir Redif divisions).

- Edirne Fortified Area with six-plus divisions (10th and 11th Infantry, Edirne, Babaeski and Gümülcine Redif and the Fortress division, 4th Rifle and 12th Cavalry regiments).

- Kırcaali Detachment with two-plus divisions (Kırcaali Redif, Kırcaali Mustahfız division and 36th Infantry Regiment).

- An independent cavalry division and the 5th Light Cavalry Brigade.

The Western Army (Macedonian and Vardar Army) was composed of ten corps with 32 infantry and two cavalry divisions. Against Serbia, the Ottomans deployed the Vardar Army (HQ in Skopje) under Halepli Zeki Pasha, with five corps of 18 infantry divisions, one cavalry division and two independent cavalry brigades under the:

- V Corps with four divisions (13th, 15th, 16th Infantry and the İştip Redif divisions)

- VI Corps with four divisions (17th, 18th Infantry and the Manastır and Drama Redif divisions)

- VII Corps with three division (19th Infantry and Üsküp and Priştine Redif divisions)

- II Corps with three divisions (Uşak, Denizli and İzmir Redif divisions)

- Sandžak Corps[citation needed] with four divisions (20th Infantry (minus regiment), 60th Infantry, Metroviça Redif Division, Taşlıca Redif Regiment, Firzovik and Taslica detachments)

- An independent Cavalry Division and the 7th and 8th Cavalry Brigades.

The Macedonian Army (headquarters in Thessaloniki under Ali Rıza Pasha) had 14 divisions in five corps, deployed against Greece, Bulgaria and Montenegro.

Against Greece, at least seven divisions were deployed:

- VIII Provisional Corps with three divisions (22nd Infantry and Nasliç and Aydın Redif divisions).

- Yanya Corps with three divisions (23rd Infantry, Yanya Redif and Bizani Fortress divisions).

- Selanik Redif division and Karaburun Detachment as independent units.

Against Bulgaria, in southeastern Macedonia, two divisions, the Struma Corps (14th Infantry and Serez Redif divisions, plus the Nevrekop Detachment), were deployed.

Against Montenegro, four-plus divisions were deployed:

- İşkodra Corps with two-plus divisions (24th Infantry, Elbasan Redif, İşkodra Fortified Area)

- İpek Detachment with two divisions (21st Infantry and Prizren Redif divisions)

According to the organisational plan, the men of the Western Group were to total 598,000, but slow mobilization and the inefficiency of the rail system drastically reduced the number of men available. According to the Western Army Staff, when the war began, it had only 200,000 men available.[28] Although more men would reach their units, war casualties prevented the Western Group from ever coming near its nominal strength. In wartime, the Ottomans had planned to bring more troops in from Syria, both Nizamiye and Redif.[28] Greek naval supremacy prevented those reinforcements from arriving. Instead, those soldiers had to deploy via the land route, and most of them never made it to the Balkans.[41]

The Ottoman General Staff, assisted by the German military mission, developed twelve war plans, which were designed to counter various combinations of opponents. Work on Plan No. 5, which was against a combination of Bulgaria, Greece, Serbia and Montenegro, was very advanced and had been sent to the army staffs for them to develop local plans.[42]

Ottoman Navy

The Ottoman fleet had performed abysmally in the 1897 Greco-Turkish War, forcing the Ottoman government to begin a drastic overhaul. Older ships were retired and newer ones acquired, chiefly from France and Germany. In addition, in 1908, the Ottomans called in a British naval mission to update their training and doctrine.[43] The British mission, headed by Admiral Sir Douglas Gamble, would find its task almost impossible. To a large extent the political upheaval in the aftermath of the Young Turk Revolution prevented it. Between 1908 and 1911, the office of Navy Minister changed hands nine times. Interdepartmental infighting and the entrenched interests of the bloated and averaged officer corps, many of whom occupied their positions as a quasi-sinecure, further obstructed drastic reform. In addition, British attempts to control the navy's construction programme were met with suspicion by the Ottoman ministers. Consequently, funds for Gamble's ambitious plans for new ships were unavailable.[44]

To counter the Greek acquisition of the Georgios Averof, the Ottomans initially tried to buy the new German armoured cruiser SMS Blücher or the battlecruiser SMS Moltke. Not able to afford the ships' high cost, the Ottomans acquired two old Brandenburg-class pre-dreadnought battleships, which became Barbaros Hayreddin and Turgut Reis.[45] Along with the cruisers Hamidiye and Mecidiye, both ships were to form the relatively modern core of the Ottoman battlefleet.[46] By the summer of 1912, however, they were already in poor condition because of chronic neglect: the rangefinders and ammunition hoists had been removed, the telephones were not working, the pumps were corroded, and most of the watertight doors could no longer be closed.[47]

Operations

Bulgarian theatre

Montenegro started the First Balkan War by declaring war against the Ottomans on 8 October [O.S. 25 September] 1912. The western part of the Balkans, including Albania, Kosovo, and Macedonia, was less important to the resolution of the war and the survival of the Ottoman Empire than the Thracian theatre, where the Bulgarians fought major battles against the Ottomans. Although geography dictated Thrace would be the major battlefield in a war with the Ottoman Empire,[40] the position of the Ottoman Army there was jeopardized by erroneous intelligence estimates of the opponents' order of battle. Unaware of the secret prewar political and military settlement over Macedonia between Bulgaria and Serbia, the Ottoman leadership assigned the bulk of its forces there. The German ambassador, Hans Baron von Wangenheim, one of the most influential people in the Ottoman capital, had reported to Berlin on 21 October that the Ottoman forces believed that the bulk of the Bulgarian army would be deployed in Macedonia with the Serbs. Then, the Ottoman headquarters, under Abdullah Pasha, expected to meet only three Bulgarian infantry divisions, accompanied by cavalry, east of Adrianople.[48] According to historian E. J. Erickson, that assumption possibly resulted from the analysis of the objectives of the Balkan Pact, but it had deadly consequences for the Ottoman Army in Thrace, which was now required to defend the area from the bulk of the Bulgarian army against impossible odds.[49] The misappraisal was also the reason of the catastrophic aggressive Ottoman strategy at the start of the campaign in Thrace.

Bulgarian offensive and advance to Çatalca

In the Thracian Front, the Bulgarian army had placed 346,182 men against the Ottoman First Army, with 105,000 men in eastern Thrace and the Kircaali detachment, of 24,000 men, in western Thrace. The Bulgarian forces were divided into the First, Second and Third Bulgarian Armies of 297,002 men in the eastern part and 49,180 (33,180 regulars and 16,000 irregulars) under the 2nd Bulgarian Division (General Stilian Kovachev) in the western part.[50] The first large-scale battle occurred against the Edirne-Kırklareli defensive line, where the Bulgarian First and Third Armies (a combined 174,254 men) defeated the Ottoman East Army (of 96,273 combatants),[51][52] near Gechkenli, Seliolu and Petra. The Ottoman XV Corps urgently left the area to defend the Gallipoli Peninsula against an expected Greek amphibious assault, which never materialised.[53] The absence of the corps created an immediate vacuum between Adrianople and Demotika, and the 11th Infantry Division from the Eastern Army's IV Corps was moved there to replace it. Thus, one complete army corps was removed from the Eastern Army's order of battle.[53]

As a consequence of the insufficient intelligence on the invading forces, the Ottoman offensive plan failed completely in the face of Bulgarian superiority. That forced Kölemen Abdullah Pasha to abandon Kirk Kilisse, which was taken without resistance by the Bulgarian Third Army.[53] The fortress of Adrianople, with some 61,250 men, was isolated and besieged by the Bulgarian Second Army, but for the time being, no assault was possible because of the lack of siege equipment in the Bulgarian inventory.[54] Another consequence of Greek naval supremacy in the Aegean was that the Ottoman forces did not receive the reinforcements that had been in the war plans, which would have been further corps transferred by sea from Syria and Palestine.[55] Thus, the Greek navy played an indirect but crucial role in the Thracian campaign by neutralising three corps, a significant portion of the Ottoman army, in the all-important opening round of the war.[55] Another more direct role was the emergency transportation of the Bulgarian 7th Rila Division from the Macedonian Front to the Thracian Front after the end of operations there.[56]

After the Battle of Kirk Kilisse, the Bulgarian High Command decided to wait a few days, but that allowed the Ottoman forces to occupy a new defensive position on the Lüleburgaz-Karaağaç-Pınarhisar line. However, the Bulgarian attack by the First and Third Armies, which together accounted for 107,386 rifleman, 3,115 cavalry, 116 machine guns and 360 artillery pieces, defeated the reinforced Ottoman Army, with 126,000 riflemen, 3,500 cavalry, 96 machine guns and 342 artillery pieces[57] and reached the Sea of Marmara. In terms of forces engaged, it was the largest battle fought in Europe between the end of the Franco-Prussian War and the beginning of the First World War.[57] As a result, the Ottoman forces were pushed to their final defensive position across the Çatalca Line, protecting the peninsula and Constantinople. There, they managed to stabilize the front with the help of fresh reinforcements from Asia. The line had been constructed during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-8, under the directions of a German engineer in Ottoman service, von Bluhm Pasha, but it had been considered obsolete by 1912.[58] An epidemic of cholera spread among the Bulgarian soldiers after the Battle of Luleburgas - Bunarhisar.[59]

Meanwhile, the forces of the Bulgarian 2nd Thracian division, 49,180 men divided into the Haskovo and Rhodope detachments, advanced towards the Aegean Sea. The Ottoman Kircaali detachment (Kircaali Redif and Kircaali Mustahfiz Divisions and 36th Regiment, with 24,000 men), tasked with defending a 400 km front across the Thessaloniki-Alexandroupoli railroad, failed to offer serious resistance, and on 26 November, the commander, Yaver Pasha, was captured with 10,131 officers and men by the Macedonian-Adrianopolitan Volunteer Corps. After the occupation of Thessaloniki by the Greek army, his surrender completed the isolation of the Ottoman forces in Macedonia from those in Thrace.

On 17 November [O.S. 4 November] 1912, the offensive against the Çatalca Line began, despite clear warnings that if the Bulgarians occupied Constantinople, Russia would attack them. The Bulgarians launched their attack along the defensive line, with 176,351 men and 462 artillery pieces against the Ottomans' 140,571 men and 316 artillery pieces,[46] but despite Bulgarian superiority, the Ottomans succeeded in repulsing them. An armistice was agreed on 3 December [O.S. 20 November] 1912 between the Ottomans and Bulgaria, the latter also representing Serbia and Montenegro, and peace negotiations began in London. Greece also participated in the conference but refused to agree to a truce and continued its operations in the Epirus sector. The negotiations were interrupted on 23 January [O.S. 10 January] 1913, when a Young Turk coup d'état in Constantinople, under Enver Pasha, overthrew the government of Kâmil Pasha. Upon the expiration of the armistice, on 3 February [O.S. 21 January] 1913, hostilities restarted.

Ottoman counteroffensive

On 20 February, Ottoman forces began their attack, both in Çatalca and south of it, at Gallipoli. There, the Ottoman X Corps, with 19,858 men and 48 guns, landed at Şarköy while an attack of around 15,000 men supported by 36 guns (part of the 30,000-strong Ottoman army isolated in Gallipoli Peninsula) at Bulair, farther south. Both attacks were supported by fire from Ottoman warships and had been intended, in the long term, to relieve pressure on Edirne. Confronting them were about 10,000 men, with 78 guns.[60] The Ottomans were probably unaware of the presence in the area of the new 4th Bulgarian Army, of 92,289 men, under General Stiliyan Kovachev. The Ottoman attack in the thin isthmus, with a front of just 1800m, was hampered by thick fog and the strong Bulgarian artillery and machine gunfire. As a result, the attack stalled and was repulsed by a Bulgarian counterattack. By the end of the day, both armies had returned to their original positions. Meanwhile, the Ottoman X Corps, which had landed at Şarköy, advanced until 23 February [O.S. 10 February] 1913, when the reinforcements that had been sent by General Kovachev succeeded in halting them.

Casualties on both sides were light. After the failure of the frontal attack in Bulair, the Ottoman forces at Şarköy re-entered their ships on 24 February [O.S. 11 February] and were transported to Gallipoli.

The Ottoman attack at Çatalca, directed against the powerful Bulgarian First and Third Armies, was initially launched only as a diversion from the Gallipoli-Şarköy operation to pin down the Bulgarian forces in situ. Nevertheless, it resulted in unexpected success. The Bulgarians, who were weakened by cholera and concerned that an Ottoman amphibious invasion might endanger their armies, deliberately withdrew about 15 km and to the south over 20 km to their secondary defensive positions, on higher ground to the west. With the end of the attack in Gallipoli, the Ottomans canceled the operation since they were reluctant to leave the Çatalca Line, but several days passed before the Bulgarians realized that the offensive had ended. By 15 February, the front had again stabilized, but fighting along the static lines continued. The battle, which resulted in heavy Bulgarian casualties, could be characterized as an Ottoman tactical victory, but it was a strategic failure since it did nothing to prevent the failure of the Gallipoli-Şarköy operation or to relieve the pressure on Edirne.

Fall of Adrianople and Serbo-Bulgarian friction

The failure of the Şarköy-Bulair operation and the deployment of the Second Serbian Army, with its much-needed heavy siege artillery, sealed Adrianople's fate. On 11 March, after a two weeks' bombardment, which destroyed many of the fortified structures around the city, the final assault started, with League forces enjoying a crushing superiority over the Ottoman garrison. The Bulgarian Second Army, with 106,425 men and two Serbian divisions with 47,275 men, conquered the city, with the Bulgarians suffering 8,093 and the Serbs 1,462 casualties.[61] The Ottoman casualties for the entire Adrianople campaign reached 23,000 dead.[62] The number of prisoners is less clear. The Ottoman Empire began the war with 61,250 men in the fortress.[63] Richard Hall noted that 60,000 men were captured. Adding to the 33,000 killed, the modern "Turkish General Staff History" notes that 28,500-man survived captivity[64] leaving 10,000 men unaccounted for[63] as possibly captured (including the unspecified number of wounded). Bulgarian losses for the entire Adrianople campaign amounted to 7,682.[65] That was the last and decisive battle that was necessary for a quick end to the war[66] even though it is speculated that the fortress would have fallen eventually because of starvation. The most important result was that the Ottoman command had lost all hope of regaining the initiative, which made any more fighting pointless.[67]

The battle had major and key results in Serbian-Bulgarian relations, planting the seeds of the two countries' confrontation some months later. The Bulgarian censor rigorously cut any references to Serbian participation in the operation in the telegrams of foreign correspondents. Public opinion in Sofia thus failed to realize the crucial services of Serbia in the battle. Accordingly, the Serbs claimed that their troops of the 20th Regiment were those who captured the Ottoman commander of the city and that Colonel Gavrilović was the allied commander who had accepted Shukri's official surrender of the garrison, a statement that the Bulgarians disputed. The Serbs officially protested and pointed out that although they had sent their troops to Adrianople to win for Bulgaria territory, whose acquisition had never been foreseen by their mutual treaty,[68] the Bulgarians had never fulfilled the clause of the treaty for Bulgaria to send 100,000 men to help the Serbians on their Vardar Front. The Bulgarians answered that their staff had informed the Serbs on 23 August.[clarification needed] The friction escalated some weeks later, when the Bulgarian delegates in London bluntly warned the Serbs that they must not expect Bulgarian support for their Adriatic claims. The Serbs angrily replied that to be a clear withdrawal from the prewar agreement of mutual understanding, according to the Kriva Palanka-Adriatic line of expansion, but the Bulgarians insisted that in their view, the Vardar Macedonian part of the agreement remained active and the Serbs were still obliged to surrender the area, as had been agreed.[68] The Serbs answered by accusing the Bulgarians of maximalism and pointed out that if they lost both northern Albania and Vardar Macedonia, their participation in the common war would have been virtually for nothing. The tension soon was expressed in a series of hostile incidents between both armies on their common line of occupation across the Vardar valley. The developments essentially ended the Serbian-Bulgarian alliance and made a future war between the two countries inevitable.

Greek theatre

Macedonian front

Ottoman intelligence had also disastrously misread Greek military intentions. In retrospect, the Ottoman staffs seemingly believed that the Greek attack would be shared equally between both major avenues of approach: Macedonia and Epirus. That made the Second Army staff evenly balance the combat strength of the seven Ottoman divisions between the Yanya Corps and VIII Corps, in Epirus and southern Macedonia, respectively. The Greek army also fielded seven divisions, but it had the initiative and so concentrated all seven against VIII Corps, leaving only a number of independent battalions of scarcely divisional strength on the Epirus front. That had fatal consequences for the Western Group by leading to the early loss of the city at the strategic centre of all three Macedonian fronts, Thessaloniki, which sealed their fate.[69] In an unexpectedly brilliant and rapid campaign, the Army of Thessaly seized the city. In the absence of secure sea lines of communications, the retention of the Thessaloniki-Constantinople corridor was essential to the overall strategic posture of the Ottomans in the Balkans. Once that was gone, the defeat of the Ottoman army became inevitable. The Bulgarians and the Serbs also played an important role in the defeat of the main Ottoman armies. Their great victories at Kirkkilise, Lüleburgaz, Kumanovo, and Monastir (Bitola) shattered the Eastern and Vardar Armies. However, the victories were not decisive by ending the war. The Ottoman field armies survived, and in Thrace, they actually grew stronger every day. Strategically, those victories were enabled partially by the weakened condition of the Ottoman armies, which had occurred by the active presence of the Greek army and navy.[70]

With the declaration of war, the Greek Army of Thessaly, under Crown Prince Constantine, advanced to the north and overcame Ottoman opposition in the fortified mountain passes of Sarantaporo. After another victory at Giannitsa (Yenidje), on 2 November [O.S. 20 October] 1912, the Ottoman commander, Hasan Tahsin Pasha, surrendered Thessaloniki and its garrison of 26,000 men to the Greeks on 9 November [O.S. 27 October] 1912. Two Corps headquarters (Ustruma and VIII), two Nizamiye divisions (14th and 22nd) and four Redif divisions (Salonika, Drama, Naslic and Serez) were thus lost to the Ottoman order of battle. Also, the Ottoman forces lost 70 artillery pieces, 30 machine guns and 70,000 rifles (Thessaloniki was the central arms depot for the Western Armies). The Ottoman forces estimated that 15,000 officers and men had been killed during the campaign in southern Macedonia, bringing their total losses to 41,000 soldiers.[71] Another consequence was that the destruction of the Macedonian army sealed the fate of the Ottoman Vardar Army, which was fighting the Serbs to the north. The fall of Thessaloniki left it strategically isolated, without logistical supply and depth to maneuver, and ensured its destruction.

Upon learning of the outcome of the Battle of Giannitsa (Yenidje), the Bulgarian High Command urgently dispatched the 7th Rila Division from the north towards the city. The division arrived there a day later, the day after its surrender to the Greeks, who were further away from the city than the Bulgarians. Until 10 November, the Greek-occupied zone had been expanded to the line from Lake Dojran to the Pangaion hills west to Kavalla. In western Macedonia, however, the lack of co-ordination between the Greek and the Serbian headquarters cost the Greeks a setback in the Battle of Vevi, on 15 November [O.S. 2 November] 1912, when the Greek 5th Infantry Division crossed its way with the VI Ottoman Corps (part of the Vardar Army with the 16th, 17th and 18th Nizamiye Divisions), retreating to Albania after the Battle of Prilep against the Serbs. The Greek division, surprised by the presence of the Ottoman Corps, isolated from the rest of Greek army and outnumbered by the now-counterattacking Ottomans centred on Monastir (Bitola), was forced to retreat. As a result, the Serbs beat the Greeks to Bitola.

Epirus front

In the Epirus front, the Greek army was initially heavily outnumbered, but the passive attitude of the Ottomans let the Greeks conquer Preveza on 21 October 1912 and push north towards Ioannina. On 5 November, Major Spyros Spyromilios led a revolt in the coastal area of Himarë and expelled the Ottoman garrison without any significant resistance,[72][73] and on 20 November, Greek troops from western Macedonia entered Korçë. However, Greek forces in the Epirote front lacked the numbers to initiate an offensive against the German-designed defensive positions of Bizani, which protected Ioannina, and so had to wait for reinforcements from the Macedonian front.[74]

After the campaign in Macedonia was over, a large part of the Army was redeployed to Epirus, where Constantine himself assumed command. In the Battle of Bizani, the Ottoman positions were breached and Ioannina was taken on 6 March [O.S. 22 February] 1913. During the siege, on 8 February 1913, the Russian pilot N. de Sackoff, flying for the Greeks, became the first pilot ever shot down in combat when his biplane was hit by ground fire after a bomb run on the walls of Fort Bizani. He came down near the small town of Preveza, on the coast north of the Ionian island of Lefkas, secured local Greek assistance, repaired his plane and resumed flying back to base.[75] The fall of Ioannina allowed the Greek army to continue its advance into northern Epirus, now the south of Albania, which it occupied. There, its advance stopped, but the Serbian line of control was very close to the north.

Naval operations in Aegean and Ionian Seas

On the outbreak of hostilities on 18 October, the Greek fleet, placed under the newly promoted Rear Admiral Pavlos Kountouriotis, sailed for the island of Lemnos, occupying it three days later (although fighting continued on the island until 27 October) and establishing an anchorage at Moudros Bay. That move had major strategic importance by providing the Greeks with a forward base near the Dardanelles Straits, the Ottoman fleet's main anchorage and refuge.[76][77] The Ottoman fleet's superiority in speed and broadside weight made Greek plans expect it to sortie from the straits early in the war. The Greek fleet's unpreparedness because of the premature outbreak of the war might well have let such an early Ottoman attack achieve a crucial victory. Instead, the Ottoman navy spent the first two months of the war in operations against the Bulgarians in the Black Sea, which gave the Greeks valuable time to complete their preparations and allowed them to consolidate their control of the Aegean Sea.[78]

By mid-November, Greek naval detachments had seized the islands of Imbros, Thasos, Agios Efstratios, Samothrace, Psara and Ikaria, and landings were undertaken on the larger islands of Lesbos and Chios only on 21 and 27 November, respectively. Substantial Ottoman garrisons were present on the latter, and their resistance was fierce. They withdrew into the mountainous interior and were not subdued until 22 December and 3 January, respectively.[77][79] Samos, officially an autonomous principality, was not attacked until 13 March 1913, out of a desire not to upset the Italians in the nearby Dodecanese. The clashes there were short-lived, as the Ottoman forces withdrew to the Anatolian mainland, and the island was securely in Greek hands by 16 March.[77][80]

At the same time, with the aid of numerous merchant ships converted to auxiliary cruisers, a loose naval blockade on the Ottoman coasts from the Dardanelles to Suez was instituted, which disrupted the Ottomans' flow of supplies (only the Black Sea routes to Romania remained open) and left some 250,000 Ottoman troops immobilised in Asia.[81][82] In the Ionian Sea, the Greek fleet operated without opposition, ferrying supplies for the army units in the Epirus front. Furthermore, the Greeks bombarded and then blockaded the port of Vlorë in Albania on 3 December and Durrës on 27 February. A naval blockade, extending from the prewar Greek border to Vlorë, was also instituted on 3 December, isolating the newly established Provisional Government of Albania that was based there from any outside support.[83]

Lieutenant Nikolaos Votsis scored a major success for Greek morale on 21 October by sailing his torpedo boat No. 11, under the cover of night, into the harbour of Thessaloniki, sinking the old Ottoman ironclad battleship Feth-i Bülend and escaping unharmed. On the same day, Greek troops of the Epirus Army seized the Ottoman naval base of Preveza. The Ottomans scuttled the four ships present there, but the Greeks were able to salvage the Italian-built torpedo-boats Antalya and Tokad, which were commissioned into the Greek Navy as Nikopolis and Tatoi, respectively.[84] A few days later, on 9 November, the wooden Ottoman armed steamer Trabzon was intercepted and sunk by the Greek torpedo boat No. 14, under Lieutenant-General Periklis Argyropoulos, off Ayvalık.[47]

Confrontations off Dardanelles

The main Ottoman fleet remained inside the Dardanelles for the early part of the war, and the Greek destroyers continuously patrolled the straits' exit to report on a possible sortie. Kountouriotis suggested mining the straits, but that was not taken up out of fear of international opinion.[85] On 7 December, the head of the Ottoman fleet, Tahir Bey, was replaced by Ramiz Naman Bey, the leader of the hawkish faction among the officer corps. A new strategy was agreed with the Ottomans to take advantage of any absence of Georgios Averof to attack the other Greek ships. The Ottoman staff formulated a plan to lure a number of the Greek destroyers on patrol into a trap. The first attempt, on 12 December, failed because of boiler trouble, but a second attempt, two days later, resulted in an indecisive engagement between the Greek destroyers and the cruiser Mecidiye.[86]

The war's first major fleet action, the Battle of Elli, was fought two days later, on 16 December [O.S. 3 December] 1912. The Ottoman fleet, with four battleships, nine destroyers and six torpedo boats, sailed to the entrance of the straits. The lighter Ottoman vessels remained behind, but the battleship squadron continued north, under the cover of forts at Kumkale, and engaged the Greek fleet coming from Imbros at 9:40. Leaving the older battleships to follow their original course, Kountouriotis led the Averof into independent action: using her superior speed, she cut across the Ottoman fleet's bow. Under fire from two sides, the Ottomans were quickly forced to withdraw to the Dardanelles.[85][87] The whole engagement lasted less than an hour in which the Ottomans suffered heavy damage to the Barbaros Hayreddin and 18 dead and 41 wounded (most during their disorderly retreat) and the Greeks had one dead and seven wounded.[85][88]

In the aftermath of Elli, on 20 December, the energetic Lieutenant Commander Rauf Bey was placed in effective command of the Ottoman fleet. Two days later, he led his forces out in the hope of again trapping the patrolling Greek destroyers between two divisions of the Ottoman fleet, one heading for Imbros and the other waiting at the entrance of the straits. The plan failed, as the Greek ships quickly broke contact. At the same time, the Mecidiye came under attack by the Greek submarine Delfin, which launched a torpedo against it but missed; it was the first such attack in history.[87] The Ottoman army continued to press upon a reluctant navy a plan for the reoccupation of Tenedos, which the Greek destroyers used as a base, by an amphibious operation scheduled for 4 January. That day, weather conditions were ideal and the fleet was ready, but the Yenihan regiment earmarked for the operation failed to arrive on time. The naval staff still ordered the fleet to sortie, and an engagement developed with the Greek fleet, without any significant results on either side.[89] Similar sorties followed on 10 and 11 January, but the results of the "cat and mouse" operations were always the same: "the Greek destroyers always managed to remain outside the Ottoman warships' range, and each time the cruisers fired a few rounds before breaking off the chase".[90]

In preparation for the next attempt to break the Greek blockade, the Ottoman Admiralty decided to create a diversion by sending the light cruiser Hamidiye, captained by Rauf Bey, to raid Greek merchant shipping in the Aegean. It was hoped that the Georgios Averof, the only major Greek unit fast enough to catch the Hamidiye, would be drawn into pursuit and leave the remainder of the Greek fleet weakened.[85][91] In the event, Hamidiye slipped through the Greek patrols on the night of 14–15 January and bombarded the harbor of the Greek island of Syros, sinking the Greek auxiliary cruiser Makedonia, which lay in anchor there (it was later raised and repaired). The Hamidiye then left the Aegean for the Eastern Mediterranean, making stops at Beirut and Port Said before it entered the Red Sea. Although it provided a major morale boost for the Ottomans, the operation failed to achieve its primary objective since Kountouriotis refused to leave his post and pursue the Hamidiye.[85][91][92]

Four days later, on 18 January [O.S. 5 January] 1913, when the Ottoman fleet again sallied from the straits towards Lemnos, it was defeated for a second time in the Battle of Lemnos. This time, the Ottoman warships concentrated their fire on the Averof, which again made use of its superior speed and tried to "cross the T" of the Ottoman fleet. Barbaros Hayreddin was again heavily damaged, and the Ottoman fleet was forced to return to the shelter of the Dardanelles and their forts with 41 killed and 101 wounded.[85][93] It was the last attempt for the Ottoman navy to leave the Dardanelles, which left the Greeks dominant in the Aegean. On 5 February [O.S. 24 January] 1913, a Greek Farman MF.7, piloted by Lieutenant Michael Moutousis and with Ensign Aristeidis Moraitinis as an observer, carried out an aerial reconnaissance of the Ottoman fleet in its anchorage at Nagara and launched four bombs on the anchored ships. Although it scored no hits, the operation is regarded as the first naval-air operation in military history.[94][95]

General Ivanov, the commander of the Second Bulgarian Army, acknowledged the role of the Greek fleet in the overall Balkan League victory by stating that "the activity of the entire Greek fleet and above all the Averof was the chief factor in the general success of the allies".[92]

Serbian and Montenegrin theatre

The Serbian forces operated against the major part of Ottoman Western Army, which was in Novi Pazar, Kosovo and northern and eastern Macedonia. Strategically, the Serbian forces were divided into four independent armies and groups: the Javor brigade and the Ibar Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in Novi Pazar; the Third Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in Kosovo; the First Army, which operated against Ottoman forces in northern Macedonia; and the Second Army, which operated from Bulgaria against Ottoman forces in eastern Macedonia. The decisive battle was expected to be fought in northern Macedonia, in the plains of Ovče Pole, where the Ottoman Vardar Army's main forces were expected to concentrate.

The plan of the Serbian Supreme Command had three Serbian armies encircle and destroy the Vardar Army in that area, with the First Army advancing from the north (along the line of Vranje-Kumanovo-Ovče Pole), the Second Army advancing from the east (along the line of Kriva Palanka-Kratovo-Ovče Pole) and the Third Army advancing from the northwest (along the line of Priština-Skopje-Ovče Pole). The main role was given to the First Army. The Second Army was expected to cut off the Vardar Army's retreat and, if necessary, to attack its rear and right flank. The Third Army was to take Kosovo and, if necessary, to assist the First Army by attacking the Vardar Army's left flank and rear. The Ibar Army and the Javor brigade had minor roles in the plan and were expected to secure the Sanjak of Novi Pazar and to replace the Third Army in Kosovo after it had advanced south.

The Serbian army, under General (later Marshal) Putnik, achieved three decisive victories in Vardar Macedonia, the primary Serbian objective in the war, by effectively destroying the Ottoman forces in the region and conquering northern Macedonia. The Serbs also helped the Montenegrins take the Sandžak and sent two divisions to help the Bulgarians at the siege of Edirne. The last battle for Macedonia was the Battle of Monastir in which the remains of the Ottoman Vardar Army were forced to retreat to central Albania. After the battle, Serbian Prime Minister Pasic asked General Putnik to take part in the race for Thessaloniki. Putnik declined and turned his army to the west, towards Albania, since he saw that a war between Greece and Bulgaria over Thessaloniki could greatly help Serbia's own plans for Vardar Macedonia.

After pressure applied by the Great Powers, the Serbs started to withdraw from northern Albania and the Sandžak but left behind their heavy artillery park to help the Montenegrins in the continuing Siege of Shkodër. On 23 April 1913, Shkodër's garrison was forced to surrender because of starvation.

Serbian atrocities against Albanians

Massacres of Albanians were perpetrated on several occasions by Serbian and Montenegrin armies and paramilitaries during the Balkan Wars.[96][97][98] According to contemporary accounts, between 10,000 and 25,000 Albanians were killed or died because of hunger and cold during that period;[98][99][100] many of the victims were children, women and the elderly.[101] According to an Albanian imam organization, there were around 21,000 simple graves in Kosovo where Albanians were massacred by the Serbian armies.[102] In August and September 1913, Serbian forces destroyed 140 villages and forced 40,000 Albanians to flee.[103]

In addition to the massacres, some civilians had their lips, ears and noses severed;[104] Philip J. Cohen, examining the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace report, said that Serbian soldiers cut off the ears, noses and tongues of Albanian civilians and gouged out their eyes.[105] Cohen also cited Durham as saying that Serbian soldiers helped bury people alive in Kosovo.[106] According to Cohen, the Serbian Army generated so much fear that some Albanian women killed their children rather than let them fall into the hands of Serbian soldiers.[107]

American relief commissioner Willar Howard said in a 1914 Daily Mirror interview that General Carlos Popovitch would shout, "Don't run away, we are brothers and friends. We don't mean to do any harm."[108] Peasants who trusted Popovitch were shot or burned to death, and elderly women unable to leave their homes were also burned. Howard said that the atrocities were committed after the war ended. According to Leo Freundlich's 1912 report, Popovitch was responsible for many of the Albanian massacres and became captain of the Serb troops in Durrës.[109] Serbian Generals Datidas Arkan and Bozo Jankovic were authorized to kill anyone who blocked Serbian control of Kosovo.[110] Yugoslavia from a Historical Perspective, a 2017 study published in Belgrade by the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia, said that villages were burned to ashes and Albanian Muslims forced to flee when Serbo-Montenegrin forces invaded Kosovo in 1912. Some chronicles cited decapitation as well as mutilation.[111]

Reasons for Ottoman defeat

The principal reason for the Ottoman defeat in the autumn of 1912 was the decision on the part of the Ottoman government to respond to the ultimatum from the Balkan League on 15 October 1912 by declaring war at a time when its mobilization, ordered on 1 October, was only partially complete.[112] During the declaration of war, 580,000 Ottoman soldiers in the Balkans faced 912,000 soldiers of the Balkan League.[113] The bad condition of the roads, together with the sparse railroad network, had led to the Ottoman mobilization being grossly behind schedule, and many of the commanders were new to their units, having been appointed only on 1 October 1912.[113] Furthermore, many Turkish divisions were still engaged in a losing war with Italy far away in the Libyan provinces. The strain of fighting a war on multiple fronts took an enormous toll on Ottoman finances, morale, casualties and materiél. The Turkish historian Handan Nezir Akmeșe wrote that the best response when they were faced with the Balkan League's ultimatum on 15 October on the part of the Ottomans would have been to try to stall for time via diplomacy while they completed their mobilization, instead of declaring war immediately.[113]

War Minister Nazım Pasha, Navy Minister Mahmud Muhtar Pasha and Austrian military attaché Josef Pomiankowski had presented overly-optimistic pictures of the Ottoman readiness for war to the Cabinet in October 1912 and advised that the Ottoman forces should take the offensive at once at the outbreak of hostilities.[113] By contrast, many senior army commanders advocated taking the defensive when the war began, arguing that the incomplete mobilization, together with serious logistic problems, made taking the offensive impossible.[113] Other reasons for the defeat were:

- Under the tyrannical and paranoid regime of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the Ottoman army had been forbidden to engage in war games or maneuvers out of the fear that it might be the cover for a coup d'état.[114] The four years since the Young Turk Revolution of 1908 had not been enough time for the army to learn how to conduct large-scale maneuvers.[114] War games in 1909 and 1910 had shown that many Ottoman officers could not efficiently move large bodies of troops such as divisions and corps, a deficiency that General Baron Colmar von der Goltz stated after watching the 1909 war games would take at least five years of training to address.[115]

- The Ottoman army was divided into two classes; Nizamiye troops, who were conscripted for five years, and Redif, who were reservists who served for seven years.[116] Training of the Redif troops had been neglected for decades, and the 50,000 Redif troops in the Balkans in 1912 had received extremely rudimentary training at best.[117] One German officer, Major Otto von Lossow, who served with the Ottomans, complained that some of the Redif troops did not know how to handle or fire a rifle.[118]

- Support services in the Ottoman army such as logistics and medical services were extremely poor.[118] There was a major shortage of doctors, no ambulances and few stretchers, and the few medical faculties were entirely inadequate for treating the large numbers of wounded.[118] Most of the wounded died as a result, which damaged morale. In particular, the badly-organized transport corps was so inefficient that it was unable to supply the troops in the field with food, which forced troops to resort to requisitioning food from local villages.[118] Even so, Ottoman soldiers lived below the subsistence level with a daily diet of 90 g of cheese and 150 g of meat but had to march all day long, leaving much of the army sickly and exhausted.[118]

- The heavy rainfall in the fall of 1912 had turned the mud roads of the Balkans into quagmires which made it extremely difficult to supply the army in the field with ammunition, which led to constant shortages at the front.[119]

- After the 1908 revolution, the Ottoman officer corps had become politicized, with many officers devoting themselves to politics at the expense of studying war.[120] Furthermore, the politicization of the army had led it to being divided into factions, most notably between those who were members of the Committee of Union and Progress and its opponents.[120] Additionally, the Ottoman officer corps had been divided between Alayli ("ranker") officers who had been promoted up from NCOs and privates and the Mektepli ("college-trained") officers who had graduated from the War College.[121] After the 1909 counterrevolution attempt, many of the Alayli officers had been purged.[121] The bulk of the army, peasant conscripts from Anatolia, were much more comfortable with the Alayli officers than with the Mektepli officers, who came from a different social milieu.[121] Furthermore, the decision to conscript non-Muslims for the first time meant that jihad, the traditional motivating force for the Ottoman Army, was not used in 1912, something that the officers of the German military mission advising the Ottomans believed was bad for the Muslims' morale.[121]

Aftermath

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to itadding to it or making an edit request. (June 2008) |

The Treaty of London ended the First Balkan War on 30 May 1913. All Ottoman territory west of the Enez-Kıyıköy line was ceded to the Balkan League, according to the status quo at the time of the armistice. The treaty also declared Albania to be an independent state. Almost all of the territory that was designated to form the new Albanian state was currently occupied by either Serbia or Greece, which only reluctantly withdrew their troops. Having unresolved disputes with Serbia over the division of northern Macedonia and with Greece over southern Macedonia, Bulgaria was prepared, if the need arose, to solve the problems by force, and began transferring its forces from Eastern Thrace to the disputed regions. Unwilling to yield to any pressure Greece and Serbia settled their mutual differences and signed a military alliance directed against Bulgaria on 1 May 1913, even before the Treaty of London had been concluded. This was soon followed by a treaty of "mutual friendship and protection" on 19 May/1 June 1913. Thus the scene for the Second Balkan War was set.

Great Powers

Although the developments that led to the war were noticed by the Great Powers, they had an official consensus over the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire, which led to a stern warning to the Balkan states. However, unofficially, each Great Power took a different diplomatic approach since there were conflicting interests in the area. Since any possible preventive effect of the common official warning was cancelled by the mixed unofficial signals, they failed to prevent or to end the war:

- Russia was a prime mover in the establishment of the Balkan League and saw it as an essential tool in case of a future war against its rival, Austria-Hungary.[122] However, Russia was unaware of the Bulgarian plans for Thrace and Constantinople, territories on which it had long held ambitions.

- France, not feeling ready for a war against Germany in 1912, took a position strongly against the war and firmly informed its ally Russia that it would not take part in a potential conflict between Russia and Austria-Hungary if it resulted from actions of the Balkan League. France, however, failed to achieve British participation in a common intervention to stop the conflict.

- The British Empire, although officially a staunch supporter of the Ottoman Empire's integrity, took secret diplomatic steps encouraging the Greek entry into the League to counteract Russian influence. At the same time, it encouraged Bulgarian aspirations over Thrace since the British preferred Thrace to be Bulgarian to Russian, despite British assurances to Russia on its expansion there.

- Austria-Hungary, struggling for an exit from the Adriatic and seeking ways for expansion in the south at the expense of the Ottoman Empire, was totally opposed to any other nation's expansion in the area. At the same time, Austria-Hungary had its own internal problems with the significant Slavic populations that campaigned against the German–Hungarian joint control of the multinational state. Serbia, whose aspirations towards Bosnia were no secret, was considered an enemy and the main tool of Russian machinations, which were behind the agitation of the Slav subjects. However, Austria-Hungary failed to achieve German backup for a firm reaction. Initially, German Emperor Wilhelm II told Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand that Germany was ready to support Austria-Hungary in all circumstances, even at the risk of a world war, but the Austro-Hungarians hesitated. Finally, in the German Imperial War Council of 8 December 1912, the consensus was that Germany would not be ready for war until at least mid-1914 and notes about that passed to Austria-Hungary. Thus, no actions could be taken when the Serbs acceded to the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum of 18 October and withdrew from Albania.

- The German Empire, which was already heavily involved in the internal Ottoman politics, officially opposed the war. However, Germany's effort to win Bulgaria for the Central Powers, since Germany saw the inevitability of Ottoman disintegration, made Germany toy with the idea of replacing the Ottomans in the Balkans with a friendly Greater Bulgaria with the borders of the Treaty of San Stefano. This was based on the German origin of Bulgarian King Ferdinand and his anti-Russian sentiments. Finally, when tensions again grew hot in July 1914 between Serbia and Austria-Hungary, when the Black Hand, an organisation backed by Serbia, assassinated Franz Ferdinand, no one had strong reservations about the possible conflict, and the First World War broke out.

List of battles

Bulgarian–Ottoman battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kardzhali | 1912 | Vasil Delov | Mehmed Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Kirk Kilisse | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Mahmut Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Lule Burgas | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Abdullah Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Siege of Edirne / Adrianople | 1913 | Georgi Vazov | Gazi Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| First Battle of Çatalca | 1912 | Radko Dimitriev | Nazim Pasha | Indecisive[123] |

| Naval Battle of Kaliakra | 1912 | Dimitar Dobrev | Hüseyin Bey | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Merhamli | 1912 | Nikola Genev | Mehmed Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

| Battle of Bulair | 1913 | Georgi Todorov | Mustafa Kemal | Bulgarian Victory |

| Second Battle of Çatalca | 1913 | Vasil Kutinchev | Ahmet Pasha | Indecisive |

| Battle of Şarköy | 1913 | Stiliyan Kovachev | Enver Pasha | Bulgarian Victory |

Greek–Ottoman battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Sarantaporo | 1912 | Constantine I | Hasan Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Yenidje | 1912 | Constantine I | Hasan Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Sorovich | 1912 | Matthaiopoulos | Hasan Pasha | Ottoman Victory |

| Battle of Pente Pigadia | 1912 | Sapountzakis | Esat Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Driskos | 1912 | Alexandros Romas | Esad Pasha | Ottoman Victory |

| Revolt of Himara | 1912 | Sapountzakis | Esat Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Elli | 1912 | Kountouriotis | Remzi Bey | Greek Victory |

| Capture of Korytsa | 1912 | Damianos | Davit Pasha | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Lemnos | 1913 | Kountouriotis | Remzi Bey | Greek Victory |

| Battle of Bizani | 1913 | Constantine I | Esat Pasha | Greek Victory |

Serbian–Ottoman battles

| Battle | Year | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Battle of Kumanovo | 1912 | Radomir Putnik | Zeki Pasha | Serbian Victory |

| Battle of Prilep | 1912 | Petar Bojović | Zeki Pasha | Serbian Victory |

| Battle of Monastir | 1912 | Petar Bojović | Zeki Pasha | Serbian Victory |

| Siege of Scutari | 1913 | Nikola I | Hasan Pasha | Status quo ante bellum[124] |

| Siege of Adrianople | 1913 | Stepa Stepanovic | Gazi Pasha | Serbian Victory |

See also

- List of places burned during the Balkan Wars

- List of Serbian–Turkish conflicts

- Journalists of the Balkan Wars

References

Notes

- ^ a b c Hall (2000), p. 16

- ^ a b c d Hall (2000), p. 18

- ^ a b c Erickson (2003), p. 70

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 69

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 52

- ^ "Там /в Плевенско и Търновско/ действително се говори, че тези черкези отвличат деца от българи, загинали през последните събития." (Из доклада на английския консул в Русе Р. Рийд от 16.06.1876 г. до английския посланик в Цариград Х. Елиот. в Н. Тодоров, Положението, с. 316)

- ^ Hacısalihoğlu, Mehmet. Kafkasya'da Rus Kolonizasyonu, Savaş ve Sürgün (PDF). Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi.

- ^ BOA, HR. SYS. 1219/5, lef 28, p. 4

- ^ Karataş, Ömer. The Settlement of the Caucasian Emigrants in the Balkans during lkans duringthe 19th Century Century

- ^ Hall, The Balkan Wars 1912–1913, p 135

- ^ Hall, The Balkan Wars 1912–1913, p 135

- ^ Βιβλίο εργασίας 3, Οι Βαλκανικοί Πόλεμοι, ΒΑΛΕΡΙ ΚΟΛΕΦ and ΧΡΙΣΤΙΝΑ ΚΟΥΛΟΥΡΗ, translation by ΙΟΥΛΙΑ ΠΕΝΤΑΖΟΥ, CDRSEE, Thessaloniki 2005, p. 120,(Greek). Retrieved from http://www.cdsee.org

- ^ Hall, The Balkan Wars 1912–1913, p 135

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p. 329

- ^ Balkan Savaşları ve Balkan Savaşları'nda Bulgaristan, Süleyman Uslu

- ^ Noel Malcolm, A short History of Kosovo, pp 246–247

- ^ Olsi Jazexhi, Ottomans into Illyrians : passages to nationhood in 20th century Albania, pp> 86–89

- ^ Noel Malcolm, A Short History of Kosovo pp. 250–251.

- ^ Hall, The Balkan Wars 1912–1913, pp 10–13

- ^ The Ear Correspondence of Leon Trotsky: Hall, The Balkan Wars, 1912–13, 1980, p. 221

- ^ Hall, The Balkan Wars, 1912–1913 p. 11

- ^ Joseph Vincent Fulle, Bismarck's Diplomacy at Its Zenith, 2005, p.22

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of THE INSIDE STORY OF THE PEACE CONFERENCE, by Dr. E.J. Dillon". Mirrorservice.org. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Hugh Seton-Watson & Christopher Seton-Watson, The Making of a New Europe, 1981, p. 116

- ^ "Correspondants de guerre", Le Petit Journal Illustré (Paris), 3 novembre 1912.

- ^ Balkan Harbi (1912–1913) (1993). Harbin Sebepleri, Askeri Hazirliklar ve Osmani Devletinin Harbi Girisi. Genelkurmay Basimevi. p. 100.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ The War between Bulgaria and Turkey, 1912–1913, Volume II, Ministry of War 1928, pp. 659–663

- ^ a b c d Erickson (2003), p. 170

- ^ a b Hall (2000), p. 17

- ^ a b Fotakis (2005), p. 42

- ^ Fotakis (2005), p. 44

- ^ a b Fotakis (2005), pp. 25–35

- ^ Fotakis (2005), p. 45

- ^ Fotakis (2005), pp. 45–46

- ^ Fotakis (2005), p. 46

- ^ Hall (2000), p. 19

- ^ Uyar & Erickson (2009), pp. 225–226

- ^ Uyar & Erickson (2009), pp. 226–227

- ^ Uyar & Erickson (2009), pp. 227–228

- ^ a b Hall (2000), p. 22

- ^ Uyar & Erickson (2009), p. 227

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 62

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 9–14

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 14–15

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 16–17

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p. 131

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 20

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 85

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 86

- ^ Hall (2000), pp. 22–24

- ^ Hall (2000), pp. 2224

- ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912–1913, Volume II Ministry of War 1928, p.660

- ^ a b c Erickson (2003), p. 82

- ^ Seton-Watson (1917), p. 238

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p. 333

- ^ Seton-Watson (1917), p. 202

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p.102

- ^ Hall (2000), p. 32

- ^ Dimitrova, Snezhana (1 September 2013). "Of Other Balkan Wars: Affective Worlds of Modern and Traditional (The Bulgarian Example)". Perceptions: Journal of Foreign Affairs. 18 (2): 29–55. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 262

- ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912–1913, Volume V, Ministry of War 1930, p.1057

- ^ Zafirov – Зафиров, Д., Александров, Е., История на Българите: Военна история, София, 2007, ISBN 954-528-752-7, Zafirov p. 444

- ^ a b Erickson (2003), p. 281

- ^ Turkish General Staff, Edirne Kalesi Etrafindaki Muharebeler, p286

- ^ Зафиров, Д., Александров, Е., История на Българите: Военна история, София, 2007, Труд, ISBN 954-528-752-7, p.482

- ^ Зафиров, Д., Александров, Е., История на Българите: Военна история, София, 2007, Труд, ISBN 954-528-752-7> Zafirov – p. 383

- ^ The war between Bulgaria and Turkey 1912–1913, Volume V, Ministry of War 1930, p. 1053

- ^ a b Seton-Watson, pp. 210–238

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 215

- ^ Erickson (2003), p. 334

- ^ Erickson, Edward (2003). Defeat in detail : the Ottoman army in the Balkans, 1912–1913. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 226. ISBN 0275978885.

- ^ Kondis, Basil (1978). Greece and Albania, 1908–1914. Institute for Balkan Studies. p. 93.

- ^ Epirus, 4000 years of Greek history and civilization. M. V. Sakellariou. Ekdotike Athenon, 1997. ISBN 978-960-213-371-2, p. 367.

- ^ Albania's captives. Pyrros Ruches, Argonaut 1965, p. 65.

- ^ Baker, David, "Flight and Flying: A Chronology", Facts On File, Inc., New York, New York, 1994, Library of Congress card number 92-31491, ISBN 0-8160-1854-5, page 61.

- ^ Fotakis (2005), pp. 47–48

- ^ a b c Hall (2000), p. 64

- ^ Fotakis (2005), pp. 46–48

- ^ Erickson (2003), pp. 157–158

- ^ Erickson (2003), pp. 158–159

- ^ Fotakis (2005), pp. 48–49

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 19

- ^ Hall (2000), pp. 65, 74

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 19–20, 156

- ^ a b c d e f Fotakis (2005), p. 50

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 21–22

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 22

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 22, 196

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 22–23

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 23

- ^ a b Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), p. 26

- ^ a b Hall (2000), p. 65

- ^ Langensiepen & Güleryüz (1995), pp. 23–24, 196

- ^ "History: Balkan Wars". Hellenic Air Force. Archived from the original on 18 July 2009. Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- ^ Boyne, Walter J. (2002). Air Warfare: an International Encyclopedia: A-L. ABC-CLIO. pp. 66, 268. ISBN 978-1-57607-345-2.

- ^ United States Department of State (1943). Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 115. Retrieved 2 January 2020.

- ^ International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan Wars; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Division of Intercourse and Education (1 January 1914). "Report of the International Commission to Inquire into the Causes and Conduct of the Balkan War". Washington, D.C. : The Endowment. Retrieved 6 September 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ a b Leo Freundlich: Albania's Golgotha Archived 31 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Hudson, Kimberly A. (5 March 2009). Justice, Intervention, and Force in International Relations: Reassessing Just War Theory in the 21st Century. Taylor & Francis. p. 128. ISBN 9780203879351. Retrieved 6 September 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Archbishop Lazër Mjeda: Report on the Serb Invasion of Kosova and Macedonia Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine