Nynorsk

| Norwegian Nynorsk | |

|---|---|

| nynorsk | |

| Pronunciation | UK: /ˈnjuːnɔːrsk, ˈniːn-/ US: /njuːˈnɔːrsk, niːˈ-/[1][2][3][4] Norwegian pronunciation: [ˈnỳːnɔʂk, ˈnỳːnɔʁsk] |

| Native to | Norway |

Native speakers | None (written only) |

Indo-European

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms |

|

| Latin (Norwegian alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Norwegian Language Council |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | nn |

| ISO 639-2 | nno |

| ISO 639-3 | nno |

| Glottolog | norw1262 |

| Linguasphere | to -be 52-AAA-ba to -be |

Nynorsk (translates to "New Norwegian")[5] is one of the two written standards of the Norwegian language, the other being Bokmål. Nynorsk was established in 1929 as one of two state-sanctioned fusions of Ivar Aasen's standard Norwegian language (Norwegian: Landsmål) with the Dano-Norwegian written language (Riksmål), the other such fusion being called Bokmål. Nynorsk is a variation which is closer to Landsmål, whereas Bokmål is closer to Riksmål.

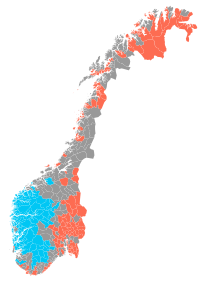

In local communities, one quarter of Norwegian municipalities have declared Nynorsk as their official language form, and these municipalities account for about 12% of the Norwegian population. Nynorsk is also taught as a mandatory subject in both high school and elementary school for all Norwegians who do not have it as their own language form.[6] Of the remaining municipalities that do not have Nynorsk as their official language form, half are neutral and half have adopted Bokmål as their official language form.[7]

Four of Norway's eighteen counties, Rogaland, Hordaland, Sogn og Fjordane and Møre og Romsdal, have Nynorsk as their official language form. These four together comprise the region of Western Norway.[8]

History

Danish had been the written language of Norway until 1814, and Danish with Norwegian intonation and pronunciation was on occasion spoken in the cities (see Dano-Norwegian). With the independence of Norway from Denmark, Danish became a foreign language and thus lost much of its prestige, and a conservative, written form of Norwegian, Landsmål, had been developed by 1850. By this time, however, the Danish language had been gradually reformed into the written language Riksmål, and no agreement was reached on which of the two forms to use. In 1885, the parliament declared the two forms official and equal.

Efforts were made to fuse the two written forms into one language. A result was that Landsmål and Riksmål lost their official status in 1929, and were replaced by the written forms Nynorsk and Bokmål, which were intended to be temporary intermediary stages before their final fusion into one hypothesised official Norwegian language known at the time as Samnorsk. This project was later abandoned[5][9] and Nynorsk and Bokmål remain the two officially sanctioned standards of what is today called the Norwegian language.

Both written languages are in reality fusions between the Norwegian and Danish languages as they were spoken and written around 1850, with Nynorsk closer to Norwegian and Bokmål closer to Danish. The official standard of Nynorsk has been significantly altered during the process to create the common language form Samnorsk. A minor purist fraction of the Nynorsk population has stayed firm with the historical Aasen norm where these alterations of Nynorsk were rejected, which is known as Høgnorsk (Template:Lang-en, analogous to High German). Ivar Aasen-sambandet is an umbrella organization of associations and individuals promoting the use of Høgnorsk, whereas Noregs Mållag and Norsk Målungdom advocate the use of Nynorsk in general.

The Landsmål (Landsmaal) language standard was constructed by the Norwegian linguist Ivar Aasen during the mid-19th century, to provide a Norwegian-based alternative to Danish, which was commonly written, and to some extent spoken, in Norway at the time.

The word Nynorsk also has another meaning. In addition to being the name of the present, official written language standard, Nynorsk can also refer to the Norwegian language in use after Old Norwegian, 11th to 14th centuries, and Middle Norwegian, 1350 to about 1550.[10] The written Norwegian that was used until the period of Danish rule (1536-1814), closely resembles Nynorsk (New Norwegian).[citation needed] A major source of old written material is Diplomatarium Norvegicum in 22 printed volumes.

Ivar Aasen's work

In 1749, Erik Pontoppidan released a comprehensive dictionary of Norwegian words that were incomprehensible to Danish people, Glossarium Norvagicum Eller Forsøg paa en Samling Af saadanne rare Norske Ord Som gemeenlig ikke forstaaes af Danske Folk, Tilligemed en Fortegnelse paa Norske Mænds og Qvinders Navne.[11] Nevertheless, it is generally acknowledged that the first systematic study of the Norwegian language was made by Ivar Aasen in the mid 19th century. After the dissolution of Denmark–Norway and the establishment of the union between Sweden and Norway in 1814, Norwegians considered that neither Danish, by now a foreign language, nor by any means Swedish, were suitable written norms for Norwegian affairs. The linguist Knud Knudsen proposed a gradual Norwegianisation of Danish. Ivar Aasen, however, favoured a more radical approach, based on the principle that the spoken language of people living in the Norwegian countryside, who made up the vast majority of the population, should be regarded as more Norwegian than that of upper-middle class city-dwellers, who for centuries had been substantially influenced by the Danish language and culture.[5][12] This idea was not unique to Aasen, and can be seen in the wider context of Norwegian romantic nationalism. In the 1840s Aasen traveled across rural Norway and studied its dialects. In 1848 and 1850 he published the first Norwegian grammar and dictionary, respectively, which described a standard that Aasen called Landsmål. New versions detailing the written standard were published in 1864 and 1873, and in the 20th century by Olav Beito in 1970.[13]

During the same period, Venceslaus Ulricus Hammershaimb standardised the orthography of the Faroese language. Spoken Faroese is closely related to Landsmål and dialects in Norway proper, and Lucas Debes and Peder Hansen Resen classified the Faroese tongue as Norwegian in the late 17th century.[14] Ultimately, however, Faroese was established as a separate language.

Aasen's work is based on the idea that Norwegian dialects had a common structure that made them a separate language alongside Danish and Swedish. The central point for Aasen therefore became to find and show the structural dependencies between the dialects. In order to abstract this structure from the variety of dialects, he developed some basic criteria, which he called the most perfect form. He defined this form as the one that best showed the connection to related words, with similar words, and with the forms in Old Norwegian. No single dialect had all the perfect forms, each dialect had preserved different aspects and parts of the language. Through such a systematic approach, one could arrive at a uniting expression for all Norwegian dialects, what Aasen called the fundamental dialect, and Einar Haugen has called Proto-Norwegian.

The idea that the study should end up in a new written language marked his work from the beginning. A fundamental idea for Aasen was that the fundamental dialect should be Modern Norwegian, not Old Norwegian or Old Norse. Therefore, he did not include grammatical categories which were extinct in all dialects. At the same time, the categories that were inherited from the old language and were still present in some dialects should be represented in the written standard. Haugen has used the word reconstruction rather than construction about this work.

Conflict

From the outset, Nynorsk was met with resistance among those who believed that the Dano-Norwegian then in use was sufficient. With the advent and growth of mass media, exposure to the standard languages increased, and Bokmål's position is dominant in many situations. This may explain why negative attitudes toward Nynorsk persist, as is seen with many minority languages. This is especially prominent among students, who are required to learn both of the official written languages.

Some critics of obligatory Nynorsk and Bokmål as school subjects have been very outspoken about their views. For instance, during the 2005 election, the Norwegian Young Conservatives made an advertisement where a candidate for parliament threw a copy of the Nynorsk dictionary into a barrel of flames. After strong reactions to this book burning, they apologized and chose not to use the video.[15]

Geographical distribution

Bokmål has a much larger basis in the cities and generally outside of the western part of the country.[16] Most Norwegians do not speak either Nynorsk or Bokmål as written, but a Norwegian dialect that identifies their origins. Nynorsk shares many of the problems that minority languages face.

In Norway, each municipality and county can choose to declare either of the two language standards as its official language or remain "standard-neutral". As of 2015, 26% (113) of the 428 municipalities have declared Nynorsk as their official standard, while 36% (158) have chosen Bokmål and another 36% (157) are neutral, numbers that have been stable since the 1970s.[7] At least 128 of the "neutral" municipalities are in areas where Bokmål is the prevailing form and pupils are taught in Bokmål. As for counties, three have declared Nynorsk: Hordaland, Sogn og Fjordane and Møre og Romsdal. Two have declared Bokmål: Østfold and Vestfold. The remaining fourteen are de jure standard-neutral. Few municipalities in "standard-neutral" counties use Nynorsk.

The main standard used in primary schools is decided by referendum within the local school district. The number of school districts and pupils using primarily Nynorsk has decreased from its height in the 1940s, even in Nynorsk municipalities. As of 2016[update], 12.2% of pupils in primary school are taught Nynorsk as their primary language.[8] Nynorsk is also part of the school curriculum in high school and elementary school for all students in Norway, where students are taught to write it.

The prevailing regions for Nynorsk are the rural areas of the western counties of Rogaland, Hordaland, Sogn og Fjordane and Møre og Romsdal, where an estimated 90% of the population writes nynorsk. Some of the rural parts of Oppland, Buskerud, Telemark, Aust- and Vest-Agder also write primarily in nynorsk. Usage of Nynorsk in the rest of the country is scarce. In Sogn og Fjordane county and the Sunnmøre region of Møre og Romsdal, all municipalities have stated Nynorsk as the official standard. In Hordaland, almost all municipalities have declared Nynorsk as the official standard – the city of Bergen being one of only three exceptions.

Status of the language form

Written Nynorsk is found in all the same types of places and for the same uses (newspapers, commercial products, computer programs, etc.) as other written languages. Most of the biggest newspapers in Norway have certain articles written in Nynorsk, like VG and Aftenposten[17], but are mainly Bokmål. There are also nationwide newspapers where Nynorsk is the only Norwegian-language form of publication, among them are Dag & Tid and Framtida.no. Many local newspapers have also chosen Nynorsk as the only language form of publication, like Firdaposten, Hallingdølen, Hordaland and Bø blad. Many newspapers are also officially neutral, conforming to either Nynorsk or Bokmål in an article as they see fit, like Klassekampen and Bergens Tidende. Commercial products produced in the Nynorsk areas of Norway are also often distributed with Nynorsk text, like types of Gamalost. Many computer programs and apps that serve the whole country often present a choice between Bokmål and Nynorsk, especially those produced by the Norwegian government.

There are also requirements by law that many Norwegian institutions have to follow. These laws are in order to keep Nynorsk and Bokmål as equals, which has been seen as an important case since the creation of the language forms. For instance the State-owned broadcaster NRK is required by law to have at least 25% of their content in Nynorsk. This means that at least one quarter of their content on broadcast and online media has to be in Nynorsk.[18] There is also a requirement for state organs and universities to have content written in Nynorsk.[19] Every student in the country should be presented the opportunity to take their exam in either Nynorsk or Bokmål.

Spoken Nynorsk

Nynorsk is first and foremost a written language form but it does appear as a spoken language. Spoken Nynorsk is often referred to as normed Nynorsk speech.[20] Bokmål speech in Eastern Norway often conforms to Urban East Norwegian,[21] whereas Bokmål speech in Bergen and Trondheim is called pen-bergensk (lit. fine Bergenish) and pen-trøndersk (lit. fine Trondheimish), respectively. Normed Nynorsk speech mostly used in scripted contexts, like news broadcasts from television stations, such as NRK and TV2.[22] It's also widely used in theaters, like Det Norske Teatret and by teachers. Since the 1970s, the motto of the Nynorsk movement has largely been "speak dialect, write Nynorsk", which has marginalized the use of normed Nynorsk speech to mainly scripted contexts. This is in contrast to the normed Bokmål speech which many speakers use in all social settings. Outside of scripts, it is quite common to rather speak a Norwegian dialect. Compared to many other countries, dialects have a higher social status in Norway and are often used even in official contexts.[23] At the same time, it is not uncommon for dialect speakers to use a register closer to the Nynorsk writing standard when deemed suitable, especially in formal contexts.[24]

Grammar

Nynorsk is a North-Germanic language, close in form to both Icelandic and the other form of written Norwegian (Bokmål). Nynorsk grammar is closer in grammar to Old West Norse than Bokmål is, as the latter developed from Danish.

For a grammatical comparison between Bokmål and Nynorsk, see Norwegian language#Morphology.

Nouns

Grammatical genders are inherent properties of nouns, and each gender has its own forms of inflection.

Standard Nynorsk and all Norwegian dialects, with the notable exception of the Bergen dialect,[25] have three grammatical genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. The situation is slightly more complicated in Bokmål, which has inherited the Danish two-gender system. Written Danish retains only the neuter and the common gender. Though the common gender took what used to be the feminine inflections in Danish, it matches the masculine inflections in Norwegian. The Norwegianization in the 20th century brought the three-gender system into Bokmål, but the process was never completed. In Nynorsk these are important distinctions, in contrast to Bokmål, in which all feminine nouns may also become masculine (due to the incomplete transition to a three-gender system) and inflect using its forms, and indeed a feminine word may be seen in both forms, for example boka or boken (“the book”) in Bokmål. This means that en liten stjerne – stjernen (“a small star – the star”, only masculine forms) and ei lita stjerne – stjerna (only feminine forms) both are correct Bokmål, as well as every possible combination: en liten stjerne – stjerna, ei liten stjerne – stjerna or even ei lita stjerne – stjernen. Choosing either two or three genders throughout the whole text is not a requirement either, so one may choose to write tida (“the time” f) and boken (“the book” m) in the same work in Bokmål. This is not allowed in Nynorsk, where the feminine forms have to be used wherever they exist.

In Nynorsk, unlike Bokmål, masculine and feminine nouns are differentiated not only in the singular form but also in the plural forms, for example:

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indefinite | Definite | Indefinite | Definite | |

| masculine | ein bil | bilen | bilar | bilane |

| a car | the car | cars | the cars | |

| feminine | ei linje | linja | linjer | linjene |

| a line | the line | lines | the lines | |

| neuter | eit hus | huset | hus | husa |

| a house | the house | houses | the houses | |

That is, nouns follow in general these patterns,[26] where all definite articles/plural indefinite articles are suffixes:

| Singular | Plural | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indefinite | Definite | Indefinite | Definite | |

| masculine | ein | -en | -ar | -ane |

| feminine | ei | -a | -er | -ene |

| neuter | eit | -et | - | -a |

The gender of each noun normally follows certain patterns. For instance will all nouns ending in -nad be masculine, like the word «jobbsøknad» (job application). Almost all nouns ending in -ing will be feminine, like the word «forventning» (expectation). The -ing nouns also get an irregular inflection pattern, with -ar and -ane in the plural indefinite and plural definite (just like the masculine) but is inflected like a feminine noun in every other way.[26] There are a few other common nouns that have an irregular inflection too, like «mann»[27] which means man and is a masculine word, but for plural it gets an umlaut (just like English: man - men): «menn» (men) and it gets a plural definite that follows the inflection pattern of a feminine word: «mennene» (the men). The word «son» which means son is another word that is inflected just like a masculine word except for the plural, where it is inflected like a feminine noun with an umlaut:[28] «søner» (sons), «sønene» (the sons).

Here is a short list of irregular nouns, many of which are irregular in Bokmål too and some even follow the same irregular inflection as in Bokmål (like the word in the first row: «ting»):

| Singular | Plural | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Indefinite | Definite | Indefinite | Definite |

| ein ting (a thing) | tingen (the thing) | ting (things) | tinga (the things) |

| ein far (a dad) | faren (the dad) | fedrar (dads) | fedrane (the dads) |

| ein bror (a brother) | broren (the brother) | brør (brothers) | brørne (the brothers) |

| eit museum (a museum) | museumet (the museum) | museum (museums) | musea (the museums) |

Genitive of nouns

Expressing ownership of a noun (like «the girl's car») is very similar to how it is in Bokmål, but the use of the reflexive possessive pronouns «sin», «si», «sitt», «sine» are more extensive than in Bokmål due to the preservation of historical grammatical case expressions.

Compound words

Compound words are constructed exactly the same way as in Bokmål.

A grammatical gender is not characterized by noun inflection alone; each gender can have further inflectional forms. That is, gender can determine the inflection of other parts of speech which agree grammatically with a noun. This concerns determiners, adjectives and past participles.

The inflection patterns and words are quite similar to those of Bokmål, but unlike Bokmål the feminine forms are not optional, they have to be used. As for adjectives and determiners, the list of words with a feminine inflection form are quite few compared to those for the masculine and neuter after the 2012 language revision. All the past participles for strong verbs are for instance no longer inflected for the feminine (with an inflection ending -i) and there is just a handful of adjectives left with a feminine form, one of which is the adjective «liten» as is shown in the inflection table below.

Adjectives

Adjectives have to agree with the noun in both gender and number just like Bokmål.[29] Unlike Bokmål, Nynorsk has a more completed system of adjective agreement comparable to that of the Swedish language (see Nynorsk past participles).

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Bilen er liten | The car (masculine) is small |

| Linja er lita | The line (feminine) is small |

| Huset er lite | The house (neuter) is small |

Just like in Bokmål, verbs have to agree after certain copula verbs, like in this case the verb for «to be»: vere («er» is present tense of vere). Other important copula verbs where predicative agreement happens are verte and bli (both mean "become"). Other copula verbs are also «ser ut» (looks like) and the reflexive verbs in Nynorsk. When verbs are used other than these copula verbs, the adjectives like in the example above will no longer be adjectives but an adverb. The adverb form of an adjective is the same as the neuter form of the adjective, just like in Bokmål.[30] For instance «Han gjør lite» (he does little). Adverbs are not inflected, like most languages. The system of agreement after copula verbs in the Scandinavian languages is a remnant of the grammatical case system. The verbs where the subject and predicate of the verb had the same case are known as copula verbs. The system of grammatical case disappeared but there was still specific gender forms that was left.

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Ein liten bil | A small car (masculine) |

| Ei lita linje | A small line (feminine) |

| Eit lite hus | A small house (neuter) |

Most adjectives will follow this pattern of inflection for adjectives, which is the same as in Bokmål:[31]

| Masculine/feminine | neuter | Plural/definite |

|---|---|---|

| - | -t | -e |

Examples of adjectives that follow this pattern are adjectives like fin[32] (nice), klar[33] (ready/clear), rar[34] (weird).

Adjectives/perfect participles that end on a diphthong (like the word «grei», which means straightforward/fine) will follow this inflection pattern:[29]

| Masculine/feminine | neuter | Plural/definite |

|---|---|---|

| - | -tt | -e |

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Hagen er fin | The garden (masculine) is nice |

| Løypa er fin | The trail (feminine) is nice |

| Været var fint | The weather (neuter) was nice |

| Løypa er nokså grei | The trail (feminine) is pretty straightforward |

| Det er greitt | It (neuter) is fine |

All adjective comparison follow this pattern:

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| - | -are | -ast |

| Positive | Comparative | Superlative |

|---|---|---|

| fin (nice) | finare (nicer) | finast (nicest) |

Participles

Past participles of verbs, which are when the verb functions as an adjective, are inflected just like an adjective.[29] This is very similar to the system of agreement in the Swedish language, where all participles have an inflection for gender, number and definiteness. In contrast, participles in Bokmål are only in general inflected for number and definiteness and shares many of the inflections it got from the Danish language. The inflections of these participles are inferred from the verb conjugation class they pertain to, described in the verb section. In Nynorsk, the verb «skrive» (to write, strong verb) has the following forms:[35]

| Masculine/feminine | Neuter | Plural and definite |

|---|---|---|

| skriven | skrive | skrivne |

In fact, all strong verbs are conjugated in this pattern:[29]

| Masculine/feminine | Neuter | Plural and definite |

|---|---|---|

| -en | -e | -ne |

Strong verbs had an optional feminine form -i prior to the 2012 language revision that still are used among some users.

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Protokollen er skriven | The protocol (masculine) is written |

| Boka er skriven | The book (feminine) is written |

| Brevet er skrive | The letter (neuter) is written |

| Bøkene er skrivne | The books are written |

| Ein skriven protokoll | A written protocol (masculine) |

| Ei skriven bok | A written book (feminine) |

| Eit skrive brev | A written letter (neuter) |

| To skrivne brev | Two written letters |

Some of the weak verbs have to agree in only number (just like in Bokmål), while many have to agree in both gender and number (like in Swedish). The weak verbs are inflected according to their conjugation class[29] (see Nynorsk verb conjugation).

All a-verbs get the following inflections:[29]

| Masculine/feminine | Neuter | Plural and definite |

|---|---|---|

| -a | ||

All e-verbs (with -de in preterite) and j-verbs get the following inflections:[29]

| Masculine/feminine | Neuter | Plural and definite |

|---|---|---|

| -d | -t | -de |

All other e-verbs (those with -te in preterite) get the following inflections:[29]

| Masculine/feminine/neuter | Plural and definite |

|---|---|

| -t | -te |

All short verbs get the following inflections:[36]

| Masculine/feminine | Neuter | Plural and definite |

|---|---|---|

| -dd | -dd/-tt | -dde |

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Boka er seld | The book (feminine) has been sold |

| Bordet er selt | The table (neuter) has been sold |

| Ein vald president | An elected president (masculine) |

| Eit utvalt barn | A chosen child (neuter) |

| Målet er oppnått | The goal (neuter) has been achieved |

| Grensa er nådd | The limit (female) has been reached |

Present participles are like all other living Scandinavian languages not inflected in Nynorsk. In general, they are formed with the suffix -ande on the verb stem; «Ein skrivande student» (a writing student).

Definiteness inflection

As can be seen from the inflection tables for adjectives and past participles, they all have their own inflection for definiteness. Just like Bokmål, when adjectives and past participles are accompanied by the articles in the following table below, the adjective/past participle gets the definite inflection and the following noun also gets the definite inflection - a form of double definiteness.[37] Nynorsk requires the use of double definiteness, where as in Bokmål this is not required due to its Danish origins, but the usage in Bokmål depends on the formality of the text. That is, in Bokmål it's perfectly fine to write «I første avsnitt» (which means; «in the first paragraph»), while the same sentence in Nynorsk would be «I det første avsnittet» which is also the most common way to construct the sentence in the Norwegian dialects[38] and is also legal Bokmål.

Like most Scandinavian languages, when the noun is definite and is described by an adjective like the sentence «the beautiful mountains», there is a separate definite article dependent on the gender/number of the noun. In Nynorsk these articles are: «den»/«det»/«dei». The following noun and adjective both gets a definite inflection. When there is no adjective and the articles «den»/«det»/«dei» are used in front of the noun (like «dei fjella», English; «those mountains»), the articles are inferred as the demonstrative «that/those» depending on if the noun is plural or not. The difference between the demonstrative «that» and the article «the» is in general inferred from context when there is an adjective involved.

| Masculine/feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| Den (that/the) | Det (that/the) | Dei (those/the) |

| Denne (this) | Dette (this) | Desse (these) |

| Masculine/feminine | English |

|---|---|

| Den fine bilen | That/the nice car |

| Den bilen | That car |

| Det rare kjøleskapet | That/the weird fridge |

| Dei storslegne fjordane | Those/the magnificent fjords |

| Dei nydelege fjella | Those/the beautiful mountains |

| Denne fine jenta | This nice girl |

| Dette store fjellet | This big mountain |

| Desse rare jentene | These weird girls |

Determiners

The determinatives have inflection patterns quite similar to Bokmål, the only difference being that the masculine form is often used for the feminine in Bokmål.

| English | Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| my/mine | min | mi | mitt | mine |

| your/yours (singular) | din | di | ditt | dine |

| his | hans | |||

| her/hers | hennar | |||

| its | dess | |||

| his/her/its (reflexive) | sin | si | sitt | sine |

| our/ours | vår | vårt | våre | |

| your/yours (plural) | dykkar | |||

| their/theirs | deira | |||

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural/definite |

|---|---|---|---|

| eigen | eiga | eige | eigne |

Examples:

- Min eigen bil (My own car)

- Mi eiga hytte (My own cabin)

- Mitt eige hus (My own house)

- Mine eigne bilar (My own cars)

Bil (car) is a masculine noun, hytte (cabin) is a feminine noun and hus (house) is a neuter noun. They all have to agree with the determinatives min and eigen in gender and number.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| ingen | inga | inkje | ingen |

Examples:

- Eg har ingen bil (I have no car)

- Eg har inga hytte (I have no cabin)

- Eg har inkje hus (I have no house)

- Eg har ingen hytter (I have no cabins)

Bil (car) is a masculine noun, hytte (cabin) is a feminine noun and hus (house) is a neuter noun. They all have to agree with the determinative ingen in gender and number.

| Masculine | Feminine | Neuter | Plural |

|---|---|---|---|

| nokon | noka | noko | nokre/nokon |

These words are used in a variety of contexts, as in Bokmål.

«Nokon/noka» means someone/any, while «noko» means something and «nokre/nokon» means some (plural).

Examples:

- Eg har ikkje sett nokon bil (I have not seen any car)

- Eg har ikkje sett noka hytte (I have not seen any cabin)

- Eg har ikkje sett noko hus (I have not seen any house)

- Eg har ikkje sett nokre/nokon bilar (I have not seen any cars)

Bil (car) is a masculine noun, hytte (cabin) is a feminine noun and hus (house) is a neuter noun. They all have to agree with the determinative nokon in gender and number.

As in other continental Scandinavian languages, verb conjugation is quite simple as they are not conjugated in person, unlike English and other European languages. Verbs are divided into two conjugation classes; strong and weak verbs, where the weak verbs further are divided into different categories; a-verbs, j-verbs, short verbs and e-verbs (some e-verbs with -de in the preterite tense and some with -te in the preterite tense). The conjugation class decides what inflection the verb will be getting for the different tenses and what kind of past participle inflection it gets. For instance will e-verbs with -de in the preterite be inflected in both gender and number for the past participles, while those with -te will be inflected only in number, as described in the past participle section. Unlike Bokmål, Nynorsk has a more marked difference between strong and weak verbs which is very common in dialects all over Norway. It's a system which resembles the Swedish verb conjugation system.

| Infinitive | Imperative | present | preterite | present perfect | Verb category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| å kaste (to throw) | kast | kastar | kasta | har kasta | a-verb |

| å kjøpe (to buy) | kjøp | kjøper | kjøpte | har kjøpt | e-verb (-te preterite) |

| å byggje (to build) | bygg | byggjer | bygde | har bygt | e-verb (-de preterite) |

| å krevje (to demand) | krev | krev | kravde | har kravt | j-verb |

| å bu (to live) | bu | bur | budde | har budd/butt | short verb |

To identify what conjugation class a verb pertains to; j-verbs will have -je/-ja in the infinitive. e-verbs have -er in present tense. a-verbs have -ar in the present tense and -a in the preterite.

| Infinitive | Imperative | present | preterite | present perfect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| å skrive (to write) | skriv | skriv | skreiv | har skrive |

| å drepe (to kill) | drep | drep | drap | har drepe |

| å lese (to read) | les | les | las | har lese |

| å tillate (to allow) | tillat | tillèt | tillét | har tillate |

All strong verbs have no ending in the present and preterite forms and the only difference between these forms is an umlaut.[43]

| Language | Infinitive | Imperative | present | preterite | present perfect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nynorsk: | å drikke | drikk | drikk | drakk | har drukke |

| English: | to drink | drink | drink/drinking | drank/was drinking | have drunk/have been drinking |

Just like in Bokmål and in most other Germanic languages, there is no difference between the simple tenses and the continuous tenses in Nynorsk. This means for instance that drikk will cover both of the English present forms drink and drinking.

All users can choose to follow a system of either an -e or an -a ending on the infinitives of verbs.[44] That is, one can for instance choose to write either «å skrive» or «å skriva» (the latter is common in west Norwegian dialects). There is also a system where one can use both -a endings and -e endings at certain verbs, this system is known as kløyvd infinitiv.[45]

As can be shown from the conjugation tables, the removal of the vocal ending of the infinitive creates the imperative form of the verb «kjøp deg ei ny datamaskin!» (buy yourself a new computer!). This is true for all weak and strong verbs.

Ergative verbs

There are ergative verbs in both Bokmål and Nynorsk. A verb in Norwegian that is ergative has two different conjugations, either weak or strong. The two different conjugation patterns, though similar, have two different meanings.[46] A verb with a weak conjugation as in the section above, will have an object, that is, the weak conjugated verb is transitive. The verb with strong conjugation will not have an object. The strongly conjugated verbs are intransitive. The system of ergative verbs is more pronounced in Nynorsk than in Bokmål. An ergative verb in Bokmål will have two different conjugations only for the preterite tense for strong verbs due to the influence of Danish that did not have strong ergative verbs, while all ergative verbs in Nynorsk have two different conjugations for all tenses like Swedish. Ergative verbs are also very common in Norwegian dialects, like in the following example.

| Infinitive | present | preterite | present perfect | perfect participle, masc/fem | perfect participle, neuter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| å brenne | brenn | brann | har brunne | brunnen | brunne |

| å brenne | brenner | brende | har brent | brend | brent |

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Låven brenn | The barn is burning |

| Hytta brann | The cabin was burning |

| Eg brenner ned huset | I'm burning down the house |

| Eg brende ned treet | I burned down the tree |

Other verbs that are ergative are often j-verbs; liggje (to lie down), leggje (to lay down). These are differentiated for all tenses, just like Bokmål.

Passive construction

Just like the other Scandinavian languages and Bokmål, there is passive construction of verbs. In general, the passive is created by taking the verb stem and adding the suffix -ast. For instance the verb «hente» (English: fetch) has the passive form «hentast». This suffix was inherited from Old Norse and is the same suffix that exists in modern-day Icelandic. In fact, all the verb forms «berast», «reddast», «opnast», «seljast» in the table below are Icelandic verb forms too.

In contrast to Bokmål, the passive forms of verbs are only used after auxiliary verbs in Nynorsk, and never without them. Without an auxiliary verb there would rather be a passive construction by the use of the verbs «vere/bli/verte» (to be/to become) and then the past participle verb form. For instance, the following sentence is not a valid sentence in Nynorsk:[47] «Pakka hentast i dag» (the package will be fetched today), there would rather be a construction like «Pakka vert henta i dag». This is due to the reduction of sentences that are ambiguous in meaning and due to the historic legacy of Old Norse. Bokmål and certain languages like Swedish and Danish have evolved an other passive construction where the passive isn't reflexive. In the general case, this can lead to confusion as to «han slåast» means that «he's fighting» or that «he's being hit», a reflexive or a non reflexive meaning. Nynorsk has two different forms that separate this meaning for the verb «slå» (slåast og slåst), but in the general case it hasn't. Nynorsk solves this general ambiguity by mainly allowing a reflexive meaning, which is also the construction that has the most historical legacy behind it. This was also the only allowed construction in Old Norse.

It's important to note that there are reflexive verbs in Nynorsk just like the other Scandinavian languages, and these are not the same as passives.[47] Examples are «synast» (think, looks like), «kjennast» (feels), etc. The reflexive verbs have their own conjugation for all tenses, which passives do not. A good dictionary will usually show an inflection table if the verb is reflexive, and if it is passive the only allowed form is the word alone with an -ast suffix.

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Eska skal berast | The box shall be carried |

| Barna må reddast | The children must be saved |

| Døra vil opnast | The door will be opened |

| Sykkelen burde seljast | The bike should be sold |

Reflexive verbs

Reflexive verbs like «å kjennast»[48] (to feel) are conjugated this way

| Infinitive | present | preterite | present perfect |

|---|---|---|---|

| å kjennast | kjennest | kjentest | har kjenst |

In general, all reflexive verbs are conjugated by this pattern. These have a reflexive meaning, see the examples below. Every reflexive verb is also a copula verb, so they have adjective agreement with adjectives like «kald» (cold), just like in Bokmål and the other Scandinavian languages.

| Norwegian | English |

|---|---|

| Dyna (feminine) byrjar å kjennast varm | The blanket is starting to feel warm |

| Maten (masculine) kjennest kald | The food feels cold |

| Bollene (plural) kjentest kalde | The buns felt cold |

| Det (neuter) har kjenst godt | It has felt good |

| Det (neuter) kan kjennast kaldt | It can feel cold |

T as final sound

One of the past participle and the preterite verb ending in Bokmål is -et. Aasen originally included these t's in his Landsmål norms, but since these are silent in the dialects, it was struck out in the first officially issued specification of Nynorsk of 1901.

Examples may compare the Bokmål forms skrevet ('written', past participle) and hoppet ('jumped', both past tense and past participle), which in written Nynorsk are skrive (Landsmål skrivet) and hoppa (Landsmål hoppat). The form hoppa is also permitted in Bokmål.

Other examples from other classes of words include the neuter singular form anna of annan ('different', with more meanings) which was spelled annat in Landsmål, and the neuter singular form ope of open ('open') which originally was spelled opet. Bokmål, in comparison, still retains these t's through the equivalent forms annet and åpent.

Pronouns

The personal pronouns in Nynorsk are the only case inflected class in Nynorsk, just like English.

| Subject form | Object form | Possessive |

|---|---|---|

| eg (I) | meg (me) | min, mi, mitt (mine) |

| du (you) | deg (you) | din, di, ditt (yours) |

| han (he/it)

ho (she/it) det (it/that) |

han (him/it)

henne/ho (her/it) det (it/that) |

hans (his)

hennar (hers) |

| vi/me (we) | oss (us) | vår, vårt (our) |

| de/dokker (you, plural) | dykk/dokker (you, plural) | dykkar/dokkar (yours, plural) |

| dei (they) | dei (them) | deira (theirs) |

As can be seen from the inflection table, the words for mine, yours etc. have to agree in gender with the object as described in the determiners section.

Like in Icelandic and Old Norse (and unlike Bokmål, Danish and Swedish), nouns are referred to by han, ho, det [49] (he, she, it) based on the gender of the noun, like the following:

| Nynorsk | Bokmål | English |

|---|---|---|

| Kor er boka mi? Ho er her | Hvor er boka mi? Den er her | Where is my book? It is here |

| Kor er bilen min? Han er her | Hvor er bilen min? Den er her | Where is my car? It is here |

| Kor er brevet mitt? Det er her | Hvor er brevet mitt? Det er her | Where is my letter? It is here |

Ordering of possessive pronouns

The main ordering of possessive pronouns is where the possessive pronoun is placed after the noun, while the noun has the definite article, just like in the example from the table above; «boka mi» (my book). If one wishes to emphasize ownership, the possessive pronoun may come first; «mi bok» (my book). If there is an adjective involved, the possessive pronoun also may come first, especially if the pronoun or adjective is emphasized; «mi eiga hytte» (my own cabin), «mi første bok» or «den første boka mi» (my first book). In all other cases the main ordering will be used. This is in contrast to other continental Scandinavian languages, like Danish and Swedish, where the possessive comes first regardless, just like English. This system of ordering possessive pronouns in Nynorsk is more similar to how it is in the Icelandic language today.

Adverbs

Adverbs are in general formed the same way as in Bokmål and other Scandinavian languages.

Syntax

The syntax of Nynorsk is mainly the same as in Bokmål. They are for instance both SVO.

Word forms compared with Bokmål Norwegian

Many words in Nynorsk are similar to their equivalents in Bokmål, with differing form, for example:

| Nynorsk | Bokmål | other dialect forms | English |

|---|---|---|---|

| eg | jeg | eg, æg, e, æ, ei, i, je, jæ | I |

| ikkje | ikke | ikkje, inte, ente, itte, itj, ikkji | not |

The distinction between Bokmål and Nynorsk is that while Bokmål has for the most part derived its forms from the written Danish language or the common Danish-Norwegian speech, Nynorsk has its orthographical standards from Aasen's reconstructed "base dialect", which are intended to represent the distinctive dialectical forms.

See also

- Norwegian dialects

- Modern Norwegian

- Spynorsk mordliste, a term used by opponents to mock Nynorsk

References

- ^ "Nynorsk". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (5th ed.). HarperCollins. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Nynorsk". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Nynorsk" (US) and "Nynorsk". Oxford Dictionaries UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. n.d. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- ^ "Nynorsk". Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary. Merriam-Webster.

- ^ a b c Vikør, Lars S. (2015). "Norwegian: Bokmål vs. Nynorsk". Språkrådet. Språkrådet. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

... two distinct written varieties: Bokmål ('Book Language') and Nynorsk ('New Norwegian').

- ^ "Læreplan i norsk (NOR1-05)". www.udir.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ a b "Ivar Aasen-tunet" (in Norwegian Nynorsk). Nynorsk kultursentrum. 2015. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 13 November 2015.

- ^ a b "Språkstatistikk – nokre nøkkeltal for norsk". Retrieved 2007-09-12.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Jahr, 1997.

- ^ "Nynorsk som talemål". Språkrådet. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

[Nynorsk] kan i tillegg bety 'norsk språk i nyere tid (etter 1500)', altså etter gammelnorsk og mellomnorsk.

- ^ "Glossarium Norvagicum eller Forsøg paa en Samling af saadanne rare Norske Ord". runeberg.org. Retrieved 2015-10-05.

- ^ Jahr, E.H., The fate of Samnorsk: a social dialect experiment in language planning. In: Clyne, M.G., 1997, Undoing and redoing corpus planning. De Gruyter, Berlin.

- ^ Venås, Kjell. 2009. Beito, Olav T. In: Stammerjohann, Harro (ed.), Lexicon Grammaticorum: A Bio-Bibliographical Companion to the History of Linguistics p. 126. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- ^ Sandøy, H., Frå tre dialektar til tre språk. In: Gunnstein Akselberg og Edit Bugge (red.), Vestnordisk språkkontakt gjennom 1200 år. Tórshavn, Fróðskapur, 2011, pp. 19-38. [1]

- ^ "Brenner nynorsk-bok i tønne". 2005-08-17. Retrieved 2008-02-02.

- ^ Kristoffersen, Gjert (2000). The Phonology of Norwegian. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823765-5.

- ^ Haugtrø, Beate (2018-05-28). "Aftenposten opnar for nynorsk". Framtida. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ Fordal, Jon Annar. "Språkreglar i NRK". NRK (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Lov om målbruk i offentleg teneste [mållova] - Lovdata". lovdata.no (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Normering av nynorsk talemål". Språkrådet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- ^ https://meta-nord.w.uib.no/files/2012/01/bokmaal-main_v10kds.pdf

- ^ "Sportsanker fekk mediemålpris". www.firda.no (in Norwegian). 2015-04-21. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- ^ O'Leary, Margaret Hayford; Andresen, Torunn (2016-05-20). Colloquial Norwegian: The Complete Course for Beginners. Routledge. ISBN 9781317582601.

- ^ "Nynorsk som talemål". Språkrådet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- ^ Skjekkeland, Martin (2016-09-16), "dialekter i Bergen", Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian), retrieved 2018-07-14

- ^ a b c "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Adverb". www.norsksidene.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ a b "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Kontakt påbygg: Dobbel bestemming, aktiv og passiv". kontakt-pabygg.cappelendamm.no (in Norwegian Bokmål). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Nynorsk som sidemål". spenn1.cappelendamm.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ a b "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ "Rettleiing om konsekvent nynorsk". Språkrådet (in Norwegian). Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ Skjekkeland, Martin (2017-12-14), "kløyvd infinitiv", Store norske leksikon (in Norwegian), retrieved 2018-07-14

- ^ "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

- ^ a b Fridtun, Kristin (2011). "NTNU Nynorsk for studentar" (PDF). www.ntnu.no (PDF). Retrieved 15 July 2018.

{{cite web}}: Check|archive-url=value (help) - ^ "Bokmålsordboka | Nynorskordboka". ordbok.uib.no. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

- ^ a b "Språkrådet". elevrom.sprakradet.no. Retrieved 2018-07-14.

Further reading

- Haugen, Einar. Norwegian, online at Språkrådet

External links

- Noregs Mållag Noregs Mållag is the major organization promoting Nynorsk.

- Norsk Målungdom Norsk Målungdom is Noregs Mållag's youth organization.

- Ivar Aasen-tunet The Ivar Aasen Centre is a national centre for documenting and experiencing the Nynorsk written culture, and the only museum in the country devoted to Ivar Aasen's life and work.

- Sidemålsrapport – 2005 report (in Bokmål) on the state of Nynorsk and Bokmål in Norwegian secondary schools.