Laz language

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2009) |

| Laz | |

|---|---|

| Lazuri, ლაზური | |

| Native to | Turkey, Georgia |

| Ethnicity | Laz people |

Native speakers | 33,000[1]–200,000[2] (2007)[3] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | lzz |

| Glottolog | lazz1240 |

| ELP | Laz |

| |

| Laz people |

|---|

|

|

|

The Laz language (ლაზური ნენა, lazuri nena; Georgian: ლაზური ენა, lazuri ena, or ჭანური ენა, ç̌anuri ena / ch’anuri ena) is a Kartvelian language language spoken by the Laz people on the southeastern shore of the Black Sea.[4] It is estimated that there are around 20,000[5] native speakers of Laz in Turkey, in a strip of land extending from Melyat to the Georgian border (officially called Lazistan until 1925), and about 2,000 in Georgia.[5]

Classification

Laz is one of the four Kartvelian languages. Along with Mingrelian, it forms the Zan branch of this Kartvelian language family. The two languages are very closely related, to the extent that some linguists refer to Mingrelian and Laz as dialects or regional variants of a single Zan language, a view held officially in the Soviet era and still so in Georgia today. In general, however, Mingrelian and Laz are considered as separate languages, due both to the long-standing separation of their communities of speakers (500 years) and to a lack of mutual intelligibility. The Laz are shifting to the Turkish of Trebizond.[6][7]

Geographical distribution

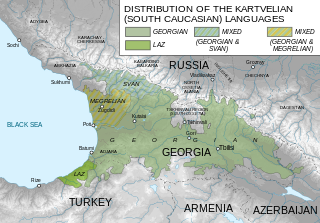

The Georgian language, along with its relatives Mingrelian, Laz, and Svan, comprises the Kartvelian (South Caucasian) language family. The initial breakup of Proto-Kartvelian is estimated to have been around 2500–2000 B.C., with the divergence of Svan from Proto-Kartvelian (Nichols, 1998). Assyrian, Urartian, Greek, and Roman documents reveal that in early historical times (2nd–1st millennia B.C.), the numerous Kartvelian tribes were in the process of migrating into the Caucasus from the southwest. The northern coast and coastal mountains of Asia Minor were dominated by Kartvelian peoples at least as far west as Samsun. Their eastward migration may have been set in motion by the fall of Troy (dated by Eratosthenes to 1183 B.C.). It thus appears that the Kartvelians represent an intrusion into the Georgian plain from northeastern Anatolia, displacing their predecessors, the unrelated Northwest Caucasian and Vainakh peoples, into the Caucasian highlands (Tuite, 1996; Nichols, 2004).[8]

The oldest known settlement of the Lazoi is the town of Lazos or "old Lazik" which Arrian puts 680 stadia (about 80 miles) south of the Sacred Port (Novorossiisk) and 1,020 stadia (100 miles) north of Pityus, i.e.somewhere in the neighbourhood of Tuapse. Kiessling sees in the Lazoi a section of the Kerketai, who in the first centuries of the Christian era had to migrate southwards under pressure from the Zygoi. The same author regards the Kerketai as a "Georgian" tribe. The fact is that at the time of Arrian (2nd century A.D.), the Lazoi were already living to the south of Um. The order of the peoples living along the coast to the east of Trebizond was as follows: Colchi (and Sanni); Machelones; Heniochi; Zydritae; Lazai, subjects of King Malassus, who owned the suzerainty of Rome; Apsilae; Abacsi; Sanigae near Sebastopolis.[7]

The ancient kingdom of Colchis was located in the same region the Laz speakers are found in today, and its inhabitants probably spoke an ancestral version of the language. Colchis was the setting for the famous Greek legend of Jason and the Argonauts.

Today most Laz speakers live in Northeast Turkey, in a strip of land along the shore of the Black Sea: in the Pazar (Atina / ათინა), Ardeşen (Art̆aşeni / არტაშენი), Çamlıhemşin (Vica / ვიჯა), Fındıklı (Viǯe / ვიწე), İkizdere (Xuras / ხურას) districts of Rize, and in the Arhavi (Arkabi / არქაბი), Hopa (Xopa / ხოფა) and Borçka (Borçxa / ბორჩხა) districts of Artvin. There are also communities in northwestern Anatolia (Akçakoca in Düzce, Sapanca in Sakarya, Karamürsel and Gölcük in Kocaeli, Bartın, and Yalova) where many immigrants settled since the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) and now also in Istanbul and Ankara. Only a few Laz live in Georgia, chiefly in Ajaria. Laz are also present in Germany where they have migrated from Turkey since the 1960s.

Social and cultural status

Laz has no official status in either Turkey or Georgia, and no written standard. It is presently used only for familiar and casual interaction; for literary, business, and other purposes, Laz speakers use their country's official language (Turkish or Georgian).

Laz is unique among the South Caucasian languages in that most of its speakers live in Turkey rather than Georgia. While the differences between the various dialects are minor, their speakers feel that their level of mutual intelligibility is low. Given that there is no common standard form of Laz, speakers of its different dialects use Turkish to communicate with each other.

Between 1930 and 1938, Zan (Laz and Mingrelian) enjoyed cultural autonomy in Georgia and was used as a literary language, but an official standard form of the tongue was never established. Since then, all attempts to create a written tradition in Zan have failed, despite the fact that most intellectuals use it as a literary language.

In Turkey, Laz has been a written language since 1984, when an alphabet based on the Turkish alphabet was created. Since then, this system has been used in most of the handful of publications that have appeared in Laz. Developed specifically for the South Caucasian languages, the Georgian alphabet is better suited to the sounds of Laz, but the fact that most of the tongue's speakers live in Turkey, where the Latin alphabet is used, has rendered the adoption of the former impossible. Nonetheless, 1991 saw the publication of a textbook called Nana-nena ('Mother tongue'), which was aimed at all Laz speakers and used both the Latin and Georgian alphabets. The first Laz–Turkish dictionary was published in 1999.

The only languages in which the Laz receive an education are Turkish (in Turkey) and Georgian (in Georgia). Virtually all the Laz are bilingual in Turkish and Laz or in Georgian and Laz. Even in villages inhabited exclusively by Laz people, it is common to hear conversations in Turkish or Georgian. Turkish has had a notable influence on the vocabulary of Laz.

Laz speakers themselves basically regard the language as a means of oral communication. The families that still speak Laz only do so among adults in informal situations, with Turkish or Georgian being used in all other contexts. This means that the younger generations fail to fully acquire the language and only gain a passive knowledge of it.

In recent times, the Laz folk musician Birol Topaloğlu has achieved a certain degree of international success with his albums Heyamo (1997, the first album ever sung entirely in the Laz language) and Aravani (2000). The Laz rock and roll musician Kazım Koyuncu performed rock and roll arrangements of Laz traditional music from 1995 until his death in 2005.

In 2004, Mehmet Bekâroğlu, the deputy chairman of Felicity Party in Turkey, sent a notice to the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation (TRT) declaring that his native language is Laz and demanding broadcasts in Laz. The same year, a group of Laz intellectuals issued a petition and held a meeting with TRT officials for the implementation of Laz broadcasts. However, as of 2008, these requests have been ignored by authorities.

Laz dialects

Laz has five major dialects:

| Name | Name in Georgian | Geographical region |

|---|---|---|

| Xopuri | ხოფური | Hopa and Ajaria |

| Viǯur-Arkabuli | ვიწურ-არქაბული | Arhavi and Fındıklı |

| Çxaluri | ჩხალური | Düzköy (Çxala) village in Borçka |

| Atinuri | ათინური | Pazar (former Atina) |

| Art̆aşenuri | არტაშენური | Ardeşen |

The last two are often treated as a single Atinan dialect. Speakers of different Laz dialects have trouble understanding each other, and often prefer to communicate in the local official language.

| English | Atina | Art̆aşeni | Arkabi | Xopa–Batumi |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I love | malimben / მალიმბენ | maoropen / მაოროფენ | p̌orom / პორომ | p̌qorop / პყოროფ |

| You love | galimben / გალიმბენ | gaoropen / გაოროფენ | orom / ორომ | qorop / ყოროფ |

| S/he-It loves | alimben / ალიმბენ | aropen / აოროფენ | oroms / ორომს | qorops / ყოროფს |

| We love | malimberan / მალიმბერან | maoropenan / მაოროფენან | p̌oromt / პორომთ | p̌qoropt / პყოროფთ |

| You love | galimberan / გალიმბერან | gaoropenan / გაოროფენან | oromt / ორომთ | qoropt / ყოროფთ |

| They love | alimberan / ალიმბერან | aoropenan / აოროფენან | oroman / ორომან | qoropan / ყოროფან |

Writing system

Laz is written in Mkhedruli script and in an extension of the Turkish alphabet.[9] For the Laz letters written in the Latin script, the first is a letter from the writing system introduced in Turkey in 1984 that was developed by Fahri Lazoğlu and Wolfgang Feurstein and the second is the transcription system used by Caucasianists.[9]

| Alphabets | Transcriptions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mkhedruli (Georgia) | Latin (Turkey) | Latin | IPA |

| ა | a | a | ɑ |

| ბ | b | b | b |

| გ | g | g | ɡ |

| დ | d | d | d |

| ე | e | e | ɛ |

| ვ | v | v | v |

| ზ | z | z | z |

| თ | t | t | t |

| ი | i | i | i |

| კ | ǩ (or kʼ) | ḳ | kʼ |

| ლ | l | l | l |

| მ | m | m | m |

| ნ | n | n | n |

| ჲ | y | y | j |

| ო | o | o | ɔ |

| პ | p̌ (or pʼ) | ṗ | pʼ |

| ჟ | j | ž | ʒ |

| რ | r | r | r |

| ს | s | s | s |

| ტ | t̆ (or tʼ) | ṭ | tʼ |

| უ | u | u | u |

| ფ | p | p | p |

| ქ | k | k | k |

| ღ | ğ | ɣ | ɣ |

| ყ | q | qʼ | qʼ |

| შ | ş | š | ʃ |

| ჩ | ç | č | t͡ʃ |

| ც | ʒ (or з or ts)[10] | c | t͡s |

| ძ | ž (or zʼ) | ʒ | d͡z |

| წ | ǯ (or зʼ or tsʼ)[10] | ċ | t͡sʼ |

| ჭ | ç̌ (or çʼ) | čʼ | t͡ʃʼ |

| ხ | x | x | x |

| ჯ | c | ǯ | d͡ʒ |

| ჰ | h | h | h |

| ჶ | f | f | f |

Linguistic features

Like many languages of the Caucasus, Laz has a rich consonantal system (in fact, the richest among the Kartvelian family) but only five vowels (a, e, i, o, u). The nouns are inflected with agglutinative suffixes to indicate grammatical function (four to seven cases, depending on the dialect) and number (singular or plural), but not by gender.

Phonology

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stop | plain | p b | t d | k g | |||

| aspirated | pʰ | tʰ | kʰ | ||||

| ejective | pʼ | tʼ | kʼ | qʼ | |||

| Affricate | plain | t͡s d͡z | t͡ʃ d͡ʒ | ||||

| ejective | t͡sʼ | t͡ʃʼ | |||||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x ɣ | h | ||

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Approximant | l | j | |||||

| Trill | r | ||||||

The Laz verb is inflected with suffixes according to person and number, and also for grammatical tense, aspect, mood, and (in some dialects) evidentiality. Up to 50 verbal prefixes are used to indicate spatial orientation/direction. Person and number suffixes provided for the subject as well as for one or two objects involved in the action, e.g. gimpulam = "I hide it from you".

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Mid | ɛ | ɔ |

| Open | ɑ | |

Grammar

Some distinctive features of Laz among its family are:

- All nouns end with a vowel.

- More extensive verb inflection, using directional prefixes.

- Substantial lexical borrowings from Greek and Turkic languages.

Vocabulary

- Ho (ჰო) – yes

- Va (ვა), Var (ვარ) – no

- Ma (მა) – I

- Si (სი) – you

- Skani (სქანი) – your

- Çkimi (ჩქიმი), Şǩimi (შკიმი) – my

- Gegacginas / Xela do ǩaobate (გეგაჯგინას/ხელა დო კაობათე) – Hello

- Ǩai serepe (კაი სერეფე) – Good night

- Ǩai moxtit (კაი მოხთით) – Welcome

- Didi mardi (დიდი მარდი) – Thanks

- Muç̌ore? (მუჭორე?) – How are you?

- Ǩai vore (კაი ვორე), Vrosi vore (ვროსი ვორე) – I'm fine

- Dido xelabas vore (დიდო ხელაბას ვორე) – I'm very happy

- Ma vulur (მა ვულურ) – I'm going

- Ma gamavulur (მა გამავულურ) – I'm going outside

- Gale (გალე) – Outside

- Ma amavulur (მა ამავულურ) – I'm going inside

- Doloxe (დოლოხე) – Inside

- Ma gevulur (მა გევულურ) – I'm going down

- Tude (თუდე) – Down, under

- Ma eşevulur (მა ეშევულურ) – I'm going up

- Jin (ჟინ) – Up

- Sonuri re? (სონური რე?) – Where are you from?

- Ťrapuzani (ტრაფუზანი) – Trabzon

- Turkona (თურქონა), Turkie (თურქიე) – Turkey

- Ruseti (რუსეთი) – Russia

- Giurcistani (გიურჯისთანი), Giurci-msva (გიურჯი-მსვა) – Georgia, Place of Georgian

- Oxorca (ოხორჯა) – woman

- Ǩoçi (კოჩი) – man

- Bozo (ბოზო), ǩulani (კულანი) – girl

- Biç̌i (ბიჭი) – boy

- Sup̌ara (სუპარა) – book

- Megabre (მეგაბრე) – friend

- Qoropa (ყოროფა) – love

- Mu dulia ikip? (მუ დულია იქიფ?) – What is your job?

- Lazuri giçkini? (ლაზური გიჩქინი?) – Do you know Laz?

- Mu gcoxons? (მუ გჯოხონს?), – What is your name?

- Ma si kqorop (Hopa dialect) (მა სი ქყოროფ) – I love you

See also

References

- ^ "Laz alphabet, language and prounciation". omniglot.com. Retrieved Nov 15, 2020.

- ^ "Laz Language on Decline in Turkey - The Language Blog by K International". May 26, 2010. Retrieved Nov 15, 2020.

- ^ Laz at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- ^ E.J. Brill's First Encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936, Volume 5, p. 21, at Google Books

- ^ a b "Laz". Ethnologue.

- ^ (cf. Pisarev in Zapiski VOIRAO [1901], xiii, 173-201)

- ^ a b http://colchianstudies.files.wordpress.com/2010/04/47-laz-minorsky.pdf

- ^ Grove, T. (2012). Materials for a Comprehensive History of the Caucasus, with an Emphasis on Greco-Roman Sources. http://timothygrove.blogspot.com/2012/07/materials-for-comprehensive-history-of.html

- ^ a b Kutscher, Silvia (2008). "The language of the Laz in Turkey: Contact-induced change or gradual language loss?" (PDF). Turkic Languages. 12: 83. Retrieved August 10, 2020.

Laz data are written in the Lazoglu & Feurstein-alphabet introduced to the Laz community in Turkey in 1984. It deviates from the Caucasianists' transcription in the following graph- emes (<Laz = Caucasianist>): <ç = č>, <c = j [j breve]>, <ǩ = kʼ>, <p̌ = p'>, <ş = š>, <t̆ = t'>, <ʒ = c>, <ǯ =c'>.

- ^ a b Extension consonnant for the Latin version of the Latin alphabet, often represented with the digit three (3) (currently missing from Unicode ?) ; the Cyrillic letter ze (З/з) has been borrowed in newspapers published in the Socialist Republic of Georgia (within USSR) to write the missing Latin letter ; modern orthographies used today also use the Latin digraphs Ts/ts for З/з and Ts’/ts’ for З’/з’.

Bibliography

- Grove, Timothy (2012). Materials for a Comprehensive History of the Caucasus, with an Emphasis on Greco-Roman Sources. A Star in the East: Materials for a Comprehensive History of the Caucasus, with an Emphasis on Greco-Roman sources (2012)

- Kojima, Gôichi (2003) Lazuri grameri Chiviyazıları, Kadıköy, İstanbul, ISBN 975-8663-55-0 (notes in English and Turkish)

- Nichols, Johanna (1998). The origin and dispersal of languages: Linguistic evidence. In N. G. Jablonski & L. C. Aiello (Eds.), The origin and diversification of language. San Francisco: California Academy of Sciences.

- Nichols, Johanna (2004). The origin of the Chechen and Ingush: A study in Alpine linguistic and ethnic geography. Anthropological Linguistics 46(2): 129-155.

- Tuite, Kevin. (1996). Highland Georgian paganism — archaism or innovation?: Review of Zurab K’ik’nadze. 1996. Kartuli mitologia, I. ǰvari da saq’mo. (Georgian mythology, I. The cross and his people [sic].). Annual of the Society for the Study of Caucasia 7: 79-91.

External links

- (in Turkish) Lazkulturdernegi.org.tr

- (in Turkish) Laz Cultur – Information about Lazs, Laz Language, Culture, Music

- (in Turkish) Laz Cultur – Information about Lazs, Laz Language, Culture, Music

- (in Turkish) Laz Cultur – Information about Lazs, Laz Language, Culture, Music and Laz Diaspora

- Lazuri Nena – The Language of the Laz by Silvia Kutscher.

- Laz-Turkish full dictionary in word format

- Samples of Laz Language in English, Dutch and Turkish, Arzu Barské - Erdogan on Yahoo! GeoCities

- Laz history and language, Lazlar, Yilmaz Erdogan on Yahoo! GeoCities

- Laz Georgian-Latin and Latin-Georgian converter