Alternative cancer treatments

Alternative cancer treatments are alternative or complementary treatments for cancer that have not been approved by the government agencies responsible for the regulation of therapeutic goods. They include diet and exercise, chemicals, herbs, devices, and manual procedures. The treatments are not supported by evidence, either because no proper testing has been conducted, or because testing did not demonstrate statistically significant efficacy. Concerns have been raised about the safety of some of them. Some treatments that have been proposed in the past have been found in clinical trials to be useless or unsafe. Some of these obsolete or disproven treatments continue to be promoted, sold, and used.

A distinction is typically made between complementary treatments which do not disrupt conventional medical treatment, and alternative treatments which may replace conventional treatment. Alternative cancer treatments are typically contrasted with experimental cancer treatments – which are treatments for which experimental testing is underway – and with complementary treatments, which are non-invasive practices used alongside other treatment. All approved chemotherapeutic cancer treatments were considered experimental cancer treatments before their safety and efficacy testing was completed.

Since the 1940s, medical science has developed chemotherapy, radiation therapy, adjuvant therapy and the newer targeted therapies, as well as refined surgical techniques for removing cancer. Before the development of these modern, evidence-based treatments, 90% of cancer patients died within five years.[2] With modern mainstream treatments, only 34% of cancer patients die within five years.[3] However, while mainstream forms of cancer treatment generally prolong life or permanently cure cancer, most treatments also have side effects ranging from unpleasant to fatal, such as pain, blood clots, fatigue, and infection.[4] These side effects and the lack of a guarantee that treatment will be successful create appeal for alternative treatments for cancer, which purport to cause fewer side effects or to increase survival rates.

Alternative cancer treatments have typically not undergone properly conducted, well-designed clinical trials, or the results have not been published due to publication bias (a refusal to publish results of a treatment outside that journal's focus area, guidelines or approach). Among those that have been published, the methodology is often poor. A 2006 systematic review of 214 articles covering 198 clinical trials of alternative cancer treatments concluded that almost none conducted dose-ranging studies, which are necessary to ensure that the patients are being given a useful amount of the treatment.[5] These kinds of treatments appear and vanish frequently, and have throughout history.[6]

Terminology

Complementary and alternative cancer treatments are often grouped together, in part because of the adoption of the phrase "complementary and alternative medicine" by the United States Congress.[7] However, according to Barrie R. Cassileth, in cancer treatment the distinction between complementary and alternative therapies is "crucial".[6]

Complementary treatments are used in conjunction with proven mainstream treatments. They tend to be pleasant for the patient, not involve substances with any pharmacological effects, inexpensive, and intended to treat side effects rather than to kill cancer cells.[8] Medical massage and self-hypnosis to treat pain are examples of complementary treatments.

About half the practitioners who dispense complementary treatments are physicians, although they tend to be generalists rather than oncologists. As many as 60% of American physicians have referred their patients to a complementary practitioner for some purpose.[6]

Alternative treatments, by contrast, are used in place of mainstream treatments. The most popular alternative cancer therapies include restrictive diets, mind-body interventions, bioelectromagnetics, nutritional supplements, and herbs.[6] The popularity and prevalence of different treatments varies widely by region.[9] Although the conventional physicians should always be kept aware of any complementary treatments used, many are supportive or at least tolerant of their use, and may actually recommend them.[10]

Extent of their usage

Survey data about how many cancer patients use alternative or complementary therapies vary from nation to nation as well from region to region. A 2000 study published by the European Journal of Cancer evaluated a sample of 1023 women from a British cancer registry suffering from breast cancer and found that 22.4% had consulted with a practitioner of complementary therapies in the previous twelve months. The study concluded that the patients had spent many thousands of pounds on such measures and that use "of practitioners of complementary therapies following diagnosis is a significant and possibly growing phenomenon".[11]

In terms of Australia, one study reported that 46% of children suffering from cancer have utilized at least one non-traditional therapy. As well, 40% of those of any age receiving palliative care had tried at least one such therapy. Some of the most popular alternative cancer treatments were found to be dietary therapies, antioxidants, high dose vitamins, and herbal therapies.[12]

Usage of unconventional cancer treatments in the United States have been influenced by the U.S. federal government's National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), initially known as the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), which was established in 1992 as a National Institutes of Health (NIH) adjunct by the U.S. Congress. Over thirty American medical schools have offered general courses on alternative medicine. That includes the Georgetown, Columbia, and Harvard university systems among others.[6]

People who choose alternative treatments

People who choose alternative treatments tend to believe that evidence-based medicine is extremely invasive or ineffective, while still believing that their own health could be improved.[13] They are loyal to their alternative healthcare providers and believe that "treatment should concentrate on the whole person".[13]

Cancer patients who choose alternative treatments instead of conventional treatments believe themselves less likely to die than patients who choose only conventional treatments.[14] They feel a greater sense of control over their destinies, and report less anxiety and depression.[14] They are more likely to engage in benefit finding, which is the psychological process of adapting to a traumatic situation and deciding that the trauma was valuable, usually because of perceived personal and spiritual growth during the crisis.[15]

However, patients who use alternative treatments have a poorer survival time, even after controlling for type and stage of disease.[16] The reason that patients using alternative treatments die sooner may be because patients who accurately perceive that they are likely to survive do not attempt unproven remedies, and patients who accurately perceive that they are unlikely to survive are attracted to unproven remedies.[16] Among patients who believe their condition to be untreatable by evidence-based medicine, "desperation drives them into the hands of anyone with a promise and a smile."[17] Con artists have long exploited fear, ignorance, and desperation to strip dying people of their money, comfort, and dignity.[17]

In a survey of American cancer patients, Baby Boomers were more likely to support complementary and alternative treatments than people from an older generation.[18] White, female, college-educated patients who had been diagnosed more than a year ago were more likely than others to report a favorable impression of at least some complementary and alternative benefits.[18]

Questionable and ineffective treatments

Many therapies have been (and continue to be) promoted to treat or prevent cancer in humans but lack good scientific and medical evidence of effectiveness. In many cases, there is good scientific evidence that the alleged treatments do not work. Unlike accepted cancer treatments, unproven and disproven treatments are generally ignored or avoided by the medical community, and are often pseudoscientific.[19]

Despite this, many of these therapies have continued to be promoted as effective, particularly by promoters of alternative medicine. Scientists consider this practice quackery,[20][21] and some of those engaged in it have been investigated and prosecuted by public health regulators such as the US Federal Trade Commission,[22] the Mexican Secretariat of Health[23] and the Canadian Competition Bureau.[24] In the United Kingdom, the Cancer Act makes the unauthorized promotion of cancer treatments a criminal offense.[25][26]

Areas of research

Specific methods

- Curcumin

- Deoxycholic acid

- Dichloroacetic acid

- HuaChanSu, traditional Chinese medicine extracted from the skin of the Bufo toad[27][28]

- Medical cannabis (especially for "Appetite Stimulation" and "Analgesia")[29]

- Melittin (via "Nanobees")

- Milk thistle

- Proton therapy

- Selenium (Selenomethionine and Se-methylselenocysteine)[30][31]

Pain relief

Most studies of complementary and alternative medicine in the treatment of cancer pain are of low quality in terms of scientific evidence. Studies of massage therapy have produced mixed results, but overall show some temporary benefit for reducing pain, anxiety, and depression and a very low risk of harm, unless the patient is at risk for bleeding disorders.[32][33] There is weak evidence for a modest benefit from hypnosis, supportive psychotherapy and cognitive therapy. Results about Reiki and touch therapy were inconclusive. The most studied such treatment, acupuncture, has demonstrated no benefit as an adjunct analgesic in cancer pain. The evidence for music therapy is equivocal, and some herbal interventions such as PC-SPES, mistletoe, and saw palmetto are known to be toxic to some cancer patients. The most promising evidence, though still weak, is for mind–body interventions such as biofeedback and relaxation techniques.[34]

Examples of complementary therapy

As stated in the scientific literature, the measures listed below are defined as 'complementary' because they are applied in conjunction with mainstream anti-cancer measures such as chemotherapy, in contrast to the ineffective therapies viewed as 'alternative' since they are offered as substitutes for mainstream measures.[6]

- Acupuncture may help with nausea but does not treat the disease.[35]

- Psychotherapy may reduce anxiety and improve quality of life as well as allow for improving patient moods.[16]

- Massage therapy may temporarily reduce pain.[34]

- In laboratory animals, some cannabinoids may stimulate appetite and reduce symptoms such as pain and nausea related to therapy, which helps reduce weight loss.[29] There is no evidence of similar effect for people.[36]

- Hypnosis and meditation may improve the quality of life of cancer patients.[37]

- Music therapy eases cancer-related symptoms by helping with mood disturbances.[16]

Alternative theories of cancer

Some alternative cancer treatments are based on unproven or disproven theories of how cancer begins or is sustained in the body. Some common concepts are:

- Mind-body connection: This idea says that cancer forms because of, or can be controlled through, the person's mental and emotional state. Treatments based on this idea are mind–body interventions. Proponents say that cancer forms because the person is unhappy or stressed, or that a positive attitude can cure cancer after it has formed. A typical claim is that stress, anger, fear, or sadness depresses the immune system, whereas that love, forgiveness, confidence, and happiness cause the immune system to improve, and that this improved immune system will destroy the cancer. This belief that generally boosting the immune system's activity will kill the cancer cells is not supported by any scientific research.[38] In fact, many cancers require the support of an active immune system (especially through inflammation) to establish the tumor microenvironment necessary for a tumor to grow.[39]

- Toxin theory of cancer: In this idea, the body's metabolic processes are overwhelmed by normal, everyday byproducts. These byproducts, called "toxins", are said to build up in the cells and cause cancer and other diseases through a process sometimes called autointoxication or autotoxemia. Treatments following this approach are usually aimed at detoxification or body cleansing, such as enemas.

- Low activity by the immune system: This claim asserts that if only the body's immune system were strong enough, it would kill the "invading" or "foreign" cancer. Unfortunately, most cancer cells retain normal cell characteristics, making them appear to the immune system to be a normal part of the body. Cancerous tumors also actively induce immune tolerance, which prevents the immune system from attacking them.[38]

Regulatory action

Government agencies around the world routinely investigate purported alternative cancer treatments in an effort to protect their citizens from fraud and abuse.

In 2008, the United States Federal Trade Commission acted against companies that made unsupported claims that their products, some of which included highly toxic chemicals, could cure cancer.[40] Targets included Omega Supply, Native Essence Herb Company, Daniel Chapter One, Gemtronics, Inc., Herbs for Cancer, Nu-Gen Nutrition, Inc., Westberry Enterprises, Inc., Jim Clark's All Natural Cancer Therapy, Bioque Technologies, Inc., Cleansing Time Pro, and Premium-essiac-tea-4less.

See also

- Diet and cancer

- Clinical trial

- Placebo effect

- Pseudoscience

- List of topics characterized as pseudoscience

References

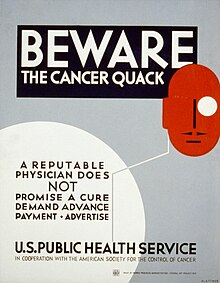

- ^ "Beware the cancer quack A reputable physician does not promise a cure, demand advance payment, advertise". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Schattner, Elaine (5 October 2010). "Who's a Survivor?". Slate Magazine.

- ^ "Cancer of All Sites - SEER Stat Fact Sheets". Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ McMillen, Matt. "8 Common Surgery Complications". WebMD Feature. WebMD. Retrieved 31 March 2013.

- ^ Vickers AJ, Kuo J, Cassileth BR (January 2006). "Unconventional anticancer agents: a systematic review of clinical trials". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 24 (1): 136–40. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.03.8406. PMC 1472241. PMID 16382123.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e f Cassileth BR (1996). "Alternative and Complementary Cancer Treatments". The Oncologist. 1 (3): 173–179. PMID 10387984.

- ^ "Overview of CAM in the United States: Recent History, Current Status, And Prospects for the Future". White House Commission on Complementary and Alternative Medicine Policy. March 2002.

- ^ Wesa KM, Cassileth BR (September 2009). "Is there a role for complementary therapy in the management of leukemia?". Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 9 (9): 1241–9. doi:10.1586/era.09.100. PMC 2792198. PMID 19761428.

- ^ Cassileth BR, Schraub S, Robinson E, Vickers A (April 2001). "Alternative medicine use worldwide: the International Union Against Cancer survey". Cancer. 91 (7): 1390–3. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(20010401)91:7<1390::AID-CNCR1143>3.0.CO;2-C. PMID 11283941.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The difference between complementary and alternative therapies", Cancer Research UK, accessed 20 November 2014

- ^ http://www.ejcancer.com/article/S0959-8049(00)00099-X/abstract?cc=y?cc=y

- ^ https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2000/172/3/australian-oncologists-self-reported-knowledge-and-attitudes-about-non

- ^ a b Furnham A, Forey J (May 1994). "The attitudes, behaviors and beliefs of patients of conventional vs. complementary (alternative) medicine". J Clin Psychol. 50 (3): 458–69. doi:10.1002/1097-4679(199405)50:3<458::AID-JCLP2270500318>3.0.CO;2-V. PMID 8071452.

- ^ a b Helyer LK, Chin S, Chui BK; et al. (2006). "The use of complementary and alternative medicines among patients with locally advanced breast cancer--a descriptive study". BMC Cancer. 6: 39. doi:10.1186/1471-2407-6-39. PMC 1475605. PMID 16504038.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Garland SN, Valentine D, Desai K; et al. (November 2013). "Complementary and alternative medicine use and benefit finding among cancer patients". J Altern Complement Med. 19 (11): 876–81. doi:10.1089/acm.2012.0964. PMID 23777242.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d Vickers, A. (2004). "Alternative Cancer Cures: 'Unproven' or 'Disproven'?". CA. 54 (2): 110–8. doi:10.3322/canjclin.54.2.110. PMID 15061600.

- ^ a b Olson, James Stuart (2002). Bathsheba's breast: women, cancer & history. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 146. ISBN 0-8018-6936-6.

- ^ a b Bauml, J. M., Chokshi, S., Schapira, M. M., Im, E.-O., Li, S. Q., Langer, C. J., Ibrahim, S. A. and Mao, J. J. (26 May 2015). "Do attitudes and beliefs regarding complementary and alternative medicine impact its use among patients with cancer? A cross-sectional survey". Cancer. 121: 2431–2438. doi:10.1002/cncr.29173.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|lay-date=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-source=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|lay-url=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Green S (1997). "Pseudoscience in Alternative Medicine: Chelation Therapy, Antineoplastons, The Gerson Diet and Coffee Enemas". Skeptical Inquirer. 21 (5): 39.

- ^ Cassileth BR, Yarett IR (August 2012). "Cancer quackery: the persistent popularity of useless, irrational 'alternative' treatments". Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.). 26 (8): 754–8. PMID 22957409.

- ^ Lerner IJ (February 1984). "The whys of cancer quackery". Cancer. 53 (3 Suppl): 815–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19840201)53:3+<815::aid-cncr2820531334>3.0.co;2-u. PMID 6362828.

- ^ "Court orders Seasilver defendants to pay $120 million". Nutraceuticals World. 11 (6): 14. 2008.

- ^ Stephen Barrett, M.D. (1 March 2004). "Zoetron Therapy (Cell Specific Cancer Therapy)". Quackwatch. Retrieved September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Zoetron Cell Specific Cancer Therapy". BBB Business Review. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Harley Street practitioner claimed he could cure cancer and HIV with lifestyle changes and herbs, court hears". Daily Telegraph. 11 December 2013.

- ^ Cancer Act 1939 section 4, 7 May 2014

- ^ "HuaChanSu". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 17 November 2012.

- ^ Meng, Zhigiang; Yang, P; Shen, Y; Bei, W; Zhang, Y; Ge, Y; Newman, RA; Cohen, L; Liu, L (2009). "Pilot Study of Huachansu in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, or Pancreatic Cancer". Cancer. 115 (22). NIHPA: 5309–5318. doi:10.1002/cncr.24602. PMC 2856335. PMID 19701908.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Cannabis and Cannabinoids:Appetite Stimulation". Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- ^ Vadgama JV, Wu Y, Shen D, Hsia S, Block J (2000). "Effect of selenium in combination with Adriamycin or Taxol on several different cancer cells". Anticancer Research. 20 (3A): 1391–414. PMID 10928049.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nilsonne G, Sun X, Nyström C; et al. (September 2006). "Selenite induces apoptosis in sarcomatoid malignant mesothelioma cells through oxidative stress". Free Radical Biology & Medicine. 41 (6): 874–85. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.04.031. PMID 16934670.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Falkensteiner, Maria; Mantovan, Franco; Müller, Irene; Them, Christa (2011). "The use of massage therapy for reducing pain, anxiety, and depression in oncological palliative care patients: a narrative review of the literature". ISRN nursing. 2011: 929868. doi:10.5402/2011/929868. ISSN 2090-5491. PMC 3168862. PMID 22007330. Retrieved 5 May 2015.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Cooke, Helen; Seers, Helen (17 December 2013). "Massage (Classical/Swedish)". CAM-Cancer Consortium.

- ^ a b Induru RR, Lagman RL. Managing cancer pain: frequently asked questions. Cleve Clin J Med. 2011;78(7):449–64. doi:10.3949/ccjm.78a.10054. PMID 21724928.

- ^ Ernst E, Pittler MH, Wider B, Boddy K (2007). "Acupuncture: its evidence-base is changing". The American Journal of Chinese Medicine. 35 (1): 21–5. doi:10.1142/S0192415X07004588. PMID 17265547.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Arney, Kat (2012-07-25). "Cannabis, cannabinoids and cancer – the evidence so far". Cancer Research UK. Retrieved 2014-03.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Vickers A, Zollman C, Payne DK (October 2001). "Hypnosis and relaxation therapies". West. J. Med. 175 (4): 269–72. doi:10.1136/ewjm.175.4.269. PMC 1071579. PMID 11577062.

Evidence from randomized controlled trials indicates that hypnosis, relaxation, and meditation techniques can reduce anxiety, particularly that related to stressful situations, such as receiving chemotherapy.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Thyphronitis G, Koutsilieris M (2004). "Boosting the immune response: an alternative combination therapy for cancer patients". Anticancer Res. 24 (4): 2443–53. PMID 15330197.

- ^ Stix, Gary (July 2007). "A Malignant Flame" (PDF). Scientific American Magazine.

- ^ "FTC Sweep Stops Peddlers of Bogus Cancer Cures: Public Education Campaign Counsels Consumers, "Talk to Your Doctor"" (Press release). Federal Trade Commission. 18 September 2008.

External links

- Cure-ious? Ask. If you or someone you care about has cancer, the last thing you need is a scam from the US Federal Trade Commission

- 187 Cancer Cure Frauds from the US Food and Drug Administration

- Herbs, Botanicals & Other Products from Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center