Ben Stiller

Ben Stiller | |

|---|---|

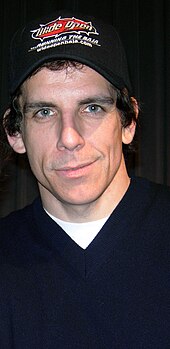

Stiller at the RTL-Spendenmarathon in 2014 | |

| Born | Benjamin Edward Meara Stiller November 30, 1965 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, comedian, filmmaker |

| Years active | 1980–present |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) | Jerry Stiller Anne Meara |

Benjamin Edward Meara "Ben" Stiller (born November 30, 1965) is an American actor, comedian, and filmmaker. He is the son of veteran comedians and actors Jerry Stiller and Anne Meara.

After beginning his acting career with a play, Stiller wrote several mockumentaries, and was offered his own show entitled The Ben Stiller Show, which he produced and hosted for its 13-episode run. Having previously acted in television, he began acting in films; he made his directorial debut with Reality Bites. Throughout his career he has written, starred in, directed, and/or produced more than 50 films, including The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, Zoolander, The Cable Guy, There's Something About Mary, the Meet the Parents trilogy, DodgeBall, Tropic Thunder, the Madagascar series, and the Night at the Museum trilogy. In addition, he has had multiple cameos in music videos, television shows, and films.

Stiller is a member of a group of comedic actors colloquially known as the Frat Pack. His films have grossed more than $2.6 billion in Canada and the United States, with an average of $79 million per film.[1] Throughout his career, he has received multiple awards and honors, including an Emmy Award, multiple MTV Movie Awards and a Teen Choice Award.

Early life

Benjamin Edward Meara Stiller[2][3] was born on November 30, 1965 in New York City.[4] His father, comedian and actor Jerry Stiller (born 1927), is from a Jewish family that emigrated from Poland and Galicia in Eastern Europe.[5] His mother, actress/comedian Anne Meara (1929-2015), who was from an Irish Catholic background, converted to Reform Judaism after marrying his father.[6][7][8] While the family was "never very religious", they celebrated both Hanukkah and Christmas,[9] and Stiller had a Bar Mitzvah.[10][11] His parents frequently took him on the sets of their appearances, including The Mike Douglas Show when he was six.[12] He considered his childhood unusual, stating "In some ways, it was a show-business upbringing—a lot of traveling, a lot of late nights—not what you'd call traditional."[13] His elder sister, Amy, has appeared in many of his productions, including Reality Bites, DodgeBall: A True Underdog Story, and Zoolander.[14][15][16]

Stiller displayed an early interest in filmmaking and made Super 8 movies with his sister and friends.[17] At nine years old, he made his acting debut as a guest on his mother's short-lived television series, Kate McShane. In the late 1970s, he performed with the New York City troupe NYC's First All Children's Theater, playing several roles, including the title role in Clever Jack and the Magic Beanstalk.[18] After being inspired by the television show Second City Television while in high school, Stiller realized that he wanted to get involved with sketch comedy.[18] During his high school years, he was also the drummer of the punk band Capital Punishment, which released a studio album named Roadkill in 1982.[19][20]

Stiller attended The Cathedral School of St. John the Divine and graduated from the Calhoun School in New York in 1983. He started performing on the cabaret circuit as opening act to the cabaret siren Jadin Wong. Stiller then enrolled as a film student at the University of California, Los Angeles.[21] After nine months, Stiller left school to move back to New York City.[11] He made his way through acting classes, auditioning and trying to find an agent.[22]

Acting career

Early work

When he was approximately 15, Stiller obtained a small part with one line on the television soap opera Guiding Light, although in an interview he characterized his performance as poor.[23] He was later cast in a role in the 1986 Broadway revival of John Guare's The House of Blue Leaves, alongside John Mahoney; the production would garner four Tony Awards.[22] During its run, Stiller produced a satirical mockumentary whose principal was fellow actor Mahoney. His comedic work was well received by the cast and crew of the play, and he followed up with a 10-minute short called The Hustler of Money, a parody of the Martin Scorsese film The Color of Money. The film featured him in a send-up of Tom Cruise's character and Mahoney in the Paul Newman role, only this time as a bowling hustler instead of a pool shark. The short got the attention of Saturday Night Live, which aired it in 1987, and two years later offered him a spot as a writer.[22] In the meantime, he also had a bit part in Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun.[24]

In 1989, Stiller wrote and appeared on Saturday Night Live as a featured performer. However, since the show did not want him to make more short films, he left after four episodes.[22] He then put together Elvis Stories, a short film about a fictitious tabloid focused on recent sightings of Elvis Presley.[25] The film starred friends and co-stars John Cusack, Jeremy Piven, Mike Myers, Andy Dick, and Jeff Kahn.[25] The film was considered a success, and led him to develop the short film Going Back to Brooklyn for MTV; it was a music video starring comedian Colin Quinn that parodied LL Cool J's recent hit "Going Back to Cali".[26]

The Ben Stiller Show

Producers at MTV were so impressed with Back to Brooklyn that they offered Stiller a 13-episode show in the experimental "vid-com" format.[27] Titled The Ben Stiller Show, this series mixed comedy sketches with music videos and parodied various television shows, music stars, and films. It starred Stiller, along with main writer Jeff Khan and Harry O'Reilly, with his parents and sister making occasional appearances.[27]

Although the show was canceled after its first season, it led to another show titled The Ben Stiller Show, on the Fox Network in 1992. The series aired 12 episodes on Fox, with a 13th unaired episode broadcast by Comedy Central in a later revival.[28] Among the principal writers on The Ben Stiller Show were Stiller and Judd Apatow, with the show featuring the ensemble cast of Stiller, Janeane Garofalo, Andy Dick, and Bob Odenkirk.[29] Both Denise Richards and Jeanne Tripplehorn appeared as extras in various episodes. Throughout its short run, The Ben Stiller Show frequently appeared at the bottom of the ratings, even as it garnered critical acclaim and eventually won an Emmy Award for "Outstanding Writing in a Variety or Music Program" posthumously.[28][30][31]

Directorial debut

Stiller had a few minor roles in the early 1990s, in films such as Stella, Highway to Hell and in a cameo, The Nutt House. In 1992, Stiller was approached to direct the film Reality Bites, based on a script by Helen Childress. Stiller devoted the next year and a half to rewriting the script with Childress, fundraising and recruiting cast members for the film. It was eventually released in early 1994, directed by Stiller and featuring him as a co-star.[22] The film was produced by Danny DeVito, who would later direct Stiller's 2003 film Duplex and produce his 2004 film Along Came Polly.[32] Reality Bites debuted as the highest-grossing film in its opening weekend and received mixed reviews.[33][34]

Stiller joined his parents in the family film Heavyweights (1995), in which he played two roles, and then had a brief uncredited role in Adam Sandler's Happy Gilmore (1996).[35][36] Next, he had lead roles in If Lucy Fell and Flirting with Disaster, before tackling his next directorial effort with The Cable Guy, which starred Jim Carrey. Stiller once again was featured in his own film, as twins. The film received mixed reviews, but was noted for paying the highest salary for an actor up to that point, as Carrey received $20 million for his work in the film.[37] The film also connected Stiller with future Frat Pack members Jack Black and Owen Wilson.

Also in 1996, MTV invited Stiller to host the VH1 Fashion Awards. Along with SNL writer Drake Sather, Stiller developed a short film for the awards about a male model known as Derek Zoolander. It was so well received that he developed another short film about the character for the 1997 VH1 Fashion Awards and finally remade the skit into a film.[22]

Comedic work

In 1998, Stiller put aside his directing ambitions to star in a surprise hit with a long-lasting cult following, the Farrelly Brothers' There's Something About Mary, alongside Cameron Diaz, which accelerated Stiller's acting career. That year, he also starred in several dramas, including Zero Effect, Your Friends & Neighbors, and Permanent Midnight. Stiller was invited to take part in hosting the Music Video awards, for which he developed a parody of the Backstreet Boys and performed a sketch with his father, commenting on his current career.[38]

In 1999, he starred in three films, including Mystery Men, where he played a superhero wannabe called Mr. Furious. He returned to directing with a new spoof television series for Fox titled Heat Vision and Jack, starring Jack Black; however, the show was not picked up by Fox after its pilot episode and the series was cancelled.[39]

In 2000, Stiller starred in three more films, including one of his most recognizable roles, a male nurse named Gaylord "Greg" Focker in Meet the Parents, opposite Robert De Niro.[40] The film was well received by critics, grossed over $330 million worldwide, and spawned two sequels.[41][42] Also in 2000, MTV again invited Stiller to make another short film, and he developed Mission: Improbable, a spoof of Tom Cruise's role in Mission: Impossible II and other films.[43]

In 2001, Stiller directed his third feature film, Zoolander, starring himself as Derek Zoolander. The film featured multiple cameos from a variety of celebrities, including Donald Trump, Paris Hilton, Lenny Kravitz, Heidi Klum, and David Bowie, among others. The film was banned in Malaysia (as the plot centered on an assassination attempt of a Malaysian prime minister),[44] while shots of the World Trade Center were digitally removed and hidden for the film's release after the September 11 terrorist attacks.[45]

After Stiller worked with Owen Wilson in Zoolander, they joined together again for The Royal Tenenbaums.[46] Over the next two years, Stiller continued with the lackluster box office film Duplex, and cameos in Orange County and Nobody Knows Anything![47][48][49] He also guest-starred on several television shows, including an appearance in an episode of the television series The King of Queens in a flashback as the father of the character Arthur (played by Jerry Stiller).[50] He also made a guest appearance on World Wrestling Entertainment's WWE Raw.[51]

In 2004, Stiller appeared in six different films, all of which were comedies, and include some of his highest-grossing films: Starsky & Hutch, Envy, DodgeBall: A True Underdog Story, Anchorman: The Legend of Ron Burgundy (in which he had an uncredited cameo), Along Came Polly and Meet the Fockers. While the critical flop Envy only grossed $14.5 million,[52] the most successful film of these was Meet the Fockers, which grossed over $516.6 million worldwide.[53] As well as these, he also made extended guest appearances on Curb Your Enthusiasm and Arrested Development in the same year. In 2005, Stiller appeared in Madagascar, which was his first experience as a voice actor in an animated film. Madagascar was a massive worldwide hit, and spawned the sequels Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa in 2008 and Madagascar 3: Europe's Most Wanted in 2012.

In 2006, Stiller had cameo roles in School for Scoundrels and Tenacious D in The Pick of Destiny, for which he served as executive producer. In December 2006, he had the lead role in Night at the Museum. Although not a critical favorite, it earned over $115 million in ten days.[54] In 2007, Stiller starred alongside Malin Åkerman in the romantic comedy The Heartbreak Kid. The film earned over $100 million worldwide despite receiving mostly negative reviews.[55][56]

2008 saw the release of Tropic Thunder, a film Stiller directed, co-wrote and co-produced, and in which he starred with Robert Downey, Jr. and Jack Black; Stiller had originally conceived of the film's premise while filming Empire of the Sun in 1987.[57] In 2009, he starred with Amy Adams in the sequel Night at the Museum 2: Battle of the Smithsonian.[58] In 2010, Stiller made a brief cameo in Joaquin Phoenix's mockumentary I'm Still Here and played the lead role in the comedy-drama Greenberg. He again portrayed Greg Focker in the critically panned yet successful Little Fockers, the second sequel to Meet the Parents. Stiller had planned to voice the main character in Megamind, but later dropped out while still remaining a producer and voicing a minor character in the film.[59]

In 2011, Stiller starred with Eddie Murphy and Alan Alda in Tower Heist, about a group of maintenance workers planning a heist in a residential skyscraper.[60] Stiller produced, directed, and starred in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, which was released in 2013.[61]

"Frat Pack"

Stiller has been described as the "acknowledged leader" of the Frat Pack, a core group of actors that have worked together in multiple films. The group includes Jack Black, Will Ferrell, Vince Vaughn, Owen Wilson, Luke Wilson, and Steve Carell.[62][63] Stiller has been acknowledged as the leader of the group because of his multiple cameos and for his consistent use of the other members in roles in films which he produces and directs.[62] He has appeared the most with Owen Wilson—in twelve films.[62][64] Of the 35 primary films that are considered Frat Pack films, Stiller has been involved with 20, in some capacity.[62]

Stiller is also the only member of this group to have appeared in a Brat Pack film (Fresh Horses).[24]

Stiller himself rejects the "Frat Pack" label, saying in a 2008 interview that the concept was "completely fabricated".[65]

Personal life

Stiller dated several actresses during his early television and film career, including Jeanne Tripplehorn, Calista Flockhart, and Amanda Peet.[66][67] In May 2000, Stiller married Christine Taylor at an oceanfront ceremony in Kauai, Hawaii.[68] He met her while filming a never-broadcast television pilot for the Fox Broadcasting network called Heat Vision and Jack.[69]

The couple have appeared onscreen together in Zoolander, DodgeBall: A True Underdog Story, Tropic Thunder, Zoolander 2, and Arrested Development. He and his wife reside in Westchester County, New York.[70] The couple have two children, a daughter, Ella Olivia, born April 9, 2002, and a son, Quinlin Dempsey, born July 10, 2005. Quinlin was a voice actor at age 3 in Madagascar: Escape 2 Africa, playing his father's character, Alex, as a cub, a role he shared with another boy, Declan Swift.[71]

Stiller is a supporter of the Democratic Party and donated money to John Kerry's 2004 U.S. Presidential campaign.[72] In February 2007, Stiller attended a fundraiser for Barack Obama and later donated to the 2008 U.S. Presidential campaigns of Democrats Obama, John Edwards, and Hillary Clinton.[73] Stiller is also a supporter of several charities, including Declare Yourself, the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation, and the Starlight Starbright Children's Foundation.[74] Stiller is actively involved in support of animal rights.[75] In 2010, Stiller joined Jennifer Aniston, Courteney Cox, Robin Williams, and other Hollywood stars in "The Cove PSA: My Friend is... ", an effort to stop the slaughter of dolphins and protect the Japanese population from the toxic levels of mercury found in dolphin meat.[76]

Stiller frequently does impersonations of many of his favorite performers, including Bono, Tom Cruise, Bruce Springsteen, and David Blaine. In an interview with Parade, he commented that Robert Klein, George Carlin, and Jimmie Walker were inspirations for his comedy career.[13] Stiller is also a self-professed Trekkie and appeared in the television special Star Trek: 30 Years and Beyond to express his love of the show, as well as a comedy roast for William Shatner.[77][78] He frequently references the show in his work, and named his production company Red Hour Productions after a time of day in the original Star Trek episode "The Return of the Archons".[79]

In October 2016, Stiller revealed that he had been diagnosed with prostate cancer in June 2014. Following surgery, he received a cancer-free status in September 2014.[80][81][82]

Filmography

Stiller has mostly appeared in comedy films. Stiller is an Emmy Award winner for his directed, produced and written television show The Ben Stiller Show.

Awards and honors

- Stiller was awarded an Emmy Award for "Outstanding Writing for a Variety, Music or Comedy Program" for his work on The Ben Stiller Show.[31]

- He has been nominated twelve times for the Teen Choice Awards, and won once, for "Choice Hissy Fit" for his work in Zoolander.

- He has been nominated for the MTV Movie Awards thirteen times, and has won three times: for "Best Fight" in There's Something About Mary, "Best Comedic Performance" in Meet the Parents, and "Best Villain" in DodgeBall: A True Underdog Story.[83] He also received the MTV Movie Awards' MTV Generation Award, the ceremony's top honor, in 2009.[84]

- Princeton University's Class of 2005 inducted Stiller as an honorary member of the class during its "Senior Week" in April 2005.[85]

- On February 23, 2007, Stiller received the Hasty Pudding Man of the Year award from Harvard's Hasty Pudding Theatricals. According to the organization, the award is given to performers who give a lasting and impressive contribution to the world of entertainment.[86]

- On March 31, 2007, Stiller received the "Wannabe Award" (given to a celebrity whom children "want to be" like) at the Kids' Choice Awards.[87]

- In 2011 he was awarded the BAFTA Britannia - Charlie Chaplin Britannia Award for Excellence in Comedy by BAFTA Los Angeles.[88]

- In 2014, Stiller was nominated for Best Actor at the 40th Saturn Awards for The Secret Life of Walter Mitty.[89]

- On February 6, 2016, Stiller set the Guinness World Record for longest selfie stick (8.56 meters) at the World Premiere of Zoolander 2.[90]

References

Footnotes

- ^ "Ben Stiller – Actor". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Friend, Tad (June 25, 2012). "Funny Is Money: Ben Stiller and the dilemma of modern stardom". The New Yorker. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Edward J. Meara, Former Resident, Dies In Boston" (PDF). Rockville Centre NY Long Island News and Owl. December 23, 1966. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

- ^ "Ben Stiller Biography: Film Actor (1965–)". Biography.com (FYI / A&E Television Networks. Archived from the original on October 2, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Married to Laughter: A Love Story Featuring Anne Meara - Jerry Stiller. Google Books. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- ^ Wallace, Debra (November 19, 1999). "Stiller 'softy' in real life". Jewish News of Greater Phoenix. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Dutka, Elaine (March 1, 1998). "Finding an Afterlife as a Playwright". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ O'Toole, Lesley (December 22, 2006). "Ben Stiller:'Doing comedy is scary'". The Independent. London. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ "What I know about women". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Longsdorf, Amy (December 3, 2010). "Christine Taylor: Sweet for the holidays". The Morning Call. Retrieved December 5, 2010.

- ^ a b Stated on Inside the Actors Studio, 2001

- ^ McIntee, Michael Z. "Monday, May 30, 2005, Show #2366 recap". Late Show with David Letterman. Archived from the original on May 14, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ a b Masello, Robert (November 28, 2006). "What makes Ben Stiller funny?". Parade. Archived from the original on June 3, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Bruni, Frank (February 22, 1994). "Generation-X man Mercurial Ben Stiller gets raves for twentysomething flick". The Spectator. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Millar, John (August 28, 2004). "Keeping it in the family is Ben's way". Daily Record. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Mitchell, Elvis (September 28, 2001). "A Lost Boy in a Plot to Keep The Fashion Industry Afloat". The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Wood, Gaby (March 14, 2004). "The geek who stole Hollywood". The Guardian. London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Ellen (December 22, 2006). "Ben Stiller Isn't Funny. Or So He Says..." (Fee required). The Washington Post. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Gordon, Jeremy and Amy Phillips (March 27, 2015). "Ben Stiller's Teenage Punk Band, Capital Punishment, Reissued by Captured Tracks". Pitchfork. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ Postigo, Cheyenne (March 27, 2015). "Captured Tracks to reissue album by Ben Stiller's teenage 'no wave/ retardo' punk band – listen". NME. Retrieved December 12, 2015.

- ^ "NOTABLE ALUMNI ACTORS". UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television. Retrieved September 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Wills, Dominic. "Ben Stiller Biography". Tiscali. Archived from the original on February 17, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Something Something Japanese". Conan. Season 2. Episode 121. July 26, 2012. TBS.

- ^ a b Svetkey, Benjamin (October 16, 1992). "Our Son the Comedian". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wickstrom, Andy (January 5, 1990). "The King Lives in 'Elvis Stories'". Boca Raton News. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ "Stiller gets serious". The Washington Post. September 28, 2001. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Wills, Dominic. "Ben Stiller – Biography". Tiscali. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Bianculli, David (August 24, 1995). "'Stiller' Gonna Make Sat. Night Livelier". New York Daily News. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Kushner, David (March 26, 1999). "Jokers Mild". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Wolk, Josh (December 5, 2003). "Stiller Standing". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Read, Kimberly; Purse, Marsia (August 4, 2007). "Ben Stiller – Actor/Comedian". About.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ben Stiller Finds 'Reality' is in the Genes". New Straits Times. February 15, 1994. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ "Reality Bites Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "Reality Bites (1993)". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Holden, Stephen (February 17, 1995). "Spoofing the TV Gurus of Fitness". The New York Times. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Lowry, Brian (February 19, 1996). "Happy Gilmore". Variety. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Waxman, Sharon (July 23, 1996). "Stiller Standing" (Fee required). The Washington Post. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Madonna Rules at Routine MTV Video Music Awards". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. September 12, 1998. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|registration=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Lawrence, Will (September 28, 2007). "Ben Stiller behaving badly". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (October 6, 2000). "Meet the Parents". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on October 27, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "Meet the Parents". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Meet the Parents". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on January 30, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mills, Nancy (October 3, 2007). "Bride of Ben". The Record. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "Zoolander faces Malaysian censorship controversy". London: guardian.co.uk. March 5, 2002. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Maher, Kevin (June 30, 2002). "Back with a bang". The Observer. London. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (March 15, 2002). "The Royal Tenenbaums". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Macaulay, Sean (January 20, 2004). "Ben there, done that". The Times. London. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Patterson, John (January 14, 2002). "Strange Fruit". London: guardian.co.uk. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Watts, Duncan J. "Nobody Knows Anything (2003)". The New York Times. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (December 12, 2006). "'Museum' Exhibits Funny Pals; Ben Stiller's Key to Success: One For All, All For One" (Fee required). USA Today. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Clark, Tim (July 31, 2000). "PPV's Cure for the Summertime Blues". Cable World. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Envy". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Meet the Fockers". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 31, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Night at the Museum – Daily Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "The Heartbreak Kid". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- ^ "The Heartbreak Kid". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on February 13, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Vary, Adam B. (March 3, 2008). "First Look: 'Tropic Thunder'". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on November 7, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Siegel, Tatiana (June 2, 2008). "Ed Helms mans 'Manure'". Variety. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "DreamWorks Animation Acquires Superhero Spoof". VFX World. April 3, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Kit, Borys (October 13, 2010). "Eddie Murphy to Star in "Tower Heist"". ABC News. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- ^ Barnes, Henry (July 20, 2011). "Ben Stiller to direct and star in The Secret Life of Walter Mitty". The Guardian. Retrieved July 16, 2015.

- ^ a b c d "Learn More". Frat Pack Tribute. Archived from the original on July 28, 2010. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (July 13, 2006). "'Frat Pack' splits". USA Today. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (June 17, 2004). "These guys would be great to hang out with". USA Today. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

- ^ "Stiller tired of "Frat Pack" label". Ben Stiller dot Net. September 23, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2010.

- ^ "Ben Stiller". Yahoo!. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Ben Stiller's funny charms". Monsters and Critics. December 16, 2006. Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Errico, Marcus (May 16, 2000). "Ben Stiller Hitched!". E!. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

- ^ Buzzle Staff and Agencies (April 16, 2002). "Ben Stiller, Christine Taylor Welcome a Girl". Buzzle.com. Retrieved March 29, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Tulloch, Lee (November 16, 2013). "Ben Stiller in the moment". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Thompson, Bob (December 16, 2006). "Group Outing". National Post. Retrieved March 29, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Ben Stiller's Federal Campaign Contribution Report". Newsmeat. Archived from the original on October 17, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaufman, Gil (July 17, 2007). "Will Smith, Ben Stiller, Even Paulie Walnuts Open Wallets for Presidential Candidates". MTV. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Ben Stiller Charity Information". Look to the Stars. Archived from the original on March 20, 2009. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "The religion and political views of Ben Stiller". hollow verse.com. Retrieved October 20, 2014.

- ^ Hollywood and “The Cove” Join Forces for Dolphin Awareness: Ben Stiller, Jennifer Aniston and friends appear in The Cove PSA directed by Andrés Useche

- ^ "'Five Year Mission' Enters 31st Season". The Daily Courier. Google News. Associated Press. October 7, 1996. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ "Holy Shat! Insults Fly at Comedy Central Roast". Startrek.com. August 15, 2006. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Silverstein, Adam (April 19, 2009). "Stiller: 'J.J. Abrams did great job'". Digital Spy. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Shoard, Catherine (October 4, 2016). "Ben Stiller speaks about diagnosis with prostate cancer". The Guardian. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ Hautman, Nicholas (October 4, 2016). "Ben Stiller Reveals He Was Diagnosed With Prostate Cancer". Us Weekly. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Hollywood actor Ben Stiller reveals he had prostate cancer but is now cancer-free". BBC News. October 4, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Awards for Ben Stiller". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ "Ben Stiller to receive MTV honour". BBC. May 23, 2009. Retrieved March 25, 2010.

- ^ Senn, Tom (April 19, 2005). "Comedian Stiller performs at Class of 2005 event". The Daily Princetonian. Archived from the original on September 28, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ben Stiller, Scarlett Johansson to receive Hasty Pudding awards at Harvard". International Herald Tribune. Associated Press. January 29, 2007. Archived from the original on September 3, 2007. Retrieved March 29, 2009.

- ^ Rogers, John (April 1, 2007). "Ben Stiller wins top Kids Choice prize – the Wannabe". The Eagle. Retrieved March 29, 2009.[dead link]

- ^ Dave McNary (August 23, 2011). "BAFTA/L.A. award to Ben Stiller". Variety. Reed Elsevier Inc. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 29, 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-29.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2016/2/ben-stiller-snaps-up-guinness-world-records-title-for-longest-selfie-stick-at-zoo-415656

Sources

- Bankston, John. Ben Stiller. Real-Life Reader Biography. Mitchell Lane Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1-58415-132-3.

- Dougherty, Terri. Ben Stiller. People in the News. Lucent Books, 2006. ISBN 1-59018-723-7.

External links

- 20th-century American male actors

- 21st-century American male actors

- 1965 births

- American film directors

- American film producers

- American male comedians

- American male film actors

- American male television actors

- American male voice actors

- American people of Austrian-Jewish descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Polish-Jewish descent

- American male screenwriters

- American television directors

- American television writers

- Animal rights advocates

- California Democrats

- Film directors from New York City

- Jewish American male actors

- Living people

- Cancer survivors

- Male actors from New York City

- People from Manhattan

- Primetime Emmy Award winners

- UCLA Film School alumni

- American sketch comedians

- Male television writers

- Comedians from New York