Billingsgate

| Ward of Billingsgate | |

|---|---|

Location within the City | |

Location within Greater London | |

| OS grid reference | TQ332806 |

| Sui generis | |

| Administrative area | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | EC3 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | City of London |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

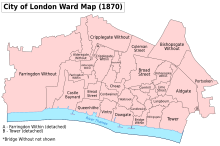

Billingsgate is one of the 25 Wards of the City of London. This small City Ward is situated on the north bank of the River Thames between London Bridge and Tower Bridge in the south-east of the Square Mile.

The modern Ward extends south to the Thames, west to Lovat Lane and Rood Lane, north to Fenchurch Street and Dunster Court, and east to Mark Lane and St Dunstan's Hill.

History

[edit]Legendary origin

[edit]Billingsgate's most ancient historical reference is as a water gate to the city of Trinovantum (the name given to London in medieval British legend), as mentioned in the Historia Regum Britanniae (Eng: History of the Kings of Britain) written c. 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. This work describes how Belinus, a legendary king of Britain said to have held the throne from about 390 BC, erected London's first fortified water gate:

In the town of Trinovantum Belinus caused to be constructed a gateway of extraordinary workmanship, which in his time the citizens called Billingsgate, from his own name. ... Finally, when his last day dawned and carried him away from this life, his body was cremated and the ash enclosed in a golden urn. This urn the citizens placed with extraordinary skill on the very top of the tower in Trinovantum which I have described.[1]

Historical origin

[edit]Originally known as Blynesgate and Byllynsgate,[2] its name apparently derives from its origins as a water gate on the Thames, where goods were landed, becoming Billingsgate Wharf, part of London's docks close to Lower Thames Street.

Historian John Stow records that Billingsgate Market was a general market for corn, coal, iron, wine, salt, pottery, fish and miscellaneous goods until the 16th century, when neighbouring streets became a specialist fish market.[3] By the late 16th century, most merchant vessels had become too large to pass under London Bridge, and so Billingsgate, with its deeply recessed harbour, replaced Queenhithe as the most important landing place in the city.

Great Fire of London

[edit]Until boundary changes in 2003, the Ward included Pudding Lane,[4] where in 1666 the Great Fire of London started.[5] A sign was erected over the property where the Great Fire began:

Here, by the permission of Heaven, hell broke loose upon this protestant city, from the malicious hearts of barbarous Papists, by the hand of their agent Hubert, who confessed, and on the ruins of this place declared the fact, for which he was hanged, viz. That here began the dreadful fire, which is described and perpetuated on and by the neighbouring pillar, erected Anno 1680, in the mayoralty of Sir Patience Ward, knight.[5]

After the Great Fire

[edit]After the Great Fire of London, shops and stalls set up trade forming arcades on the harbour's west side, whilst on the main quay, an open market soon developed, called "Roomland".

Fish market

[edit]

Billingsgate Fish Market was formally established by an act of Parliament in 1699, the Billingsgate, etc. Act 1698 (10 Will. 3. c. 13), to be "a free and open market for all sorts of fish whatsoever".[6] Oranges, lemons, and Spanish onions were also landed there, alongside the other main commodities, coal and salt. In 1849, the fish market was moved off the streets into its own riverside building, which was subsequently demolished (c. 1873) and replaced by an arcaded-market hall (designed by City architect Horace Jones, built by John Mowlem) in 1875.[3]

In 1982, Billingsgate Fish Market was relocated to its present location close to Canary Wharf in east London. The original riverside market building was then refurbished by the architect Richard Rogers to provide office accommodation and an entertainment venue.[7]

The raucous cries of the fish vendors gave rise to the word Billingsgate as a synonym for profanity or offensive language.[8]

Within the ward are the Custom House and the Watermen's Hall, built in 1780 and the city's only surviving Georgian livery company hall. Centennium House[9] in Lower Thames Street has Roman baths within its basement foundations.

Churches

[edit]Within the Ward remain two churches: St Mary-at-Hill[10] and St Margaret Pattens,[11] after the demolition of St George Botolph Lane in 1904.[12]

Politics

[edit]Billingsgate is one of the City's 25 Wards returning an Alderman and two Common Councilmen (the City equivalent of a Councillor) to the City of London Corporation, the elected in March 2022 were Luis Felipe Tilleria and Nighat Qureishi.[13]

In popular culture

[edit]Lord Blackadder, the titular hero of Blackadder II, is said to have resided at Billingsgate, and in Thackeray's Vanity Fair (Ch. 3), Mr. Sedley has "brought home the best turbot in Billingsgate".

Billingsgate is also referred to in the song "Sister Suffragette" in the 1964 version of Mary Poppins.

Due to the real and perceived vulgar language used by the fishmongers, which Francis Grose referred to in his Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, Billingsgate came to be used as a noun—billingsgate—referring to coarse or foul language.

References

[edit]- ^ Historia Regum Britanniae, III.ii.

- ^ Spelling was not standardised until much later: Borer 1978.

- ^ a b "Billingsgate history". Archived from the original on 22 June 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2007.

- ^ The name was derived from the butchers in Eastcheap "having their scalding house for hogs there; and their puddings with other filth being conveyed thence down to their dung boats in the Thames": Stow.

- ^ a b Book 2, Ch. 7: "Billingsgate Ward", A New History of London: Including Westminster and Southwark (1773), pp. 551-53 accessed: 21 May 2007

- ^ Billie Cohen (January 2005). "Lox, Stock and Barrel". National Geographic Magazine.

- ^ James Stephen Finn. "Old Billingsgate". Old Billingsgate. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "billingsgate - Word of the Day | Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. 12 June 2006. Retrieved 21 December 2016.

- ^ "Home - Centennium House". Archived from the original on 17 May 2014. Retrieved 4 August 2014.

- ^ Built by Wren, but gutted in 1941 (Whinney)

- ^ So called after the templates that were used by the clogmakers of the district (Reynolds)

- ^ As the resident population of the area declined (Huelin).

- ^ "Your Councillors". City of London Corporation. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

External links

[edit]- Ward Constable profile

- Ward map

- Ward Club Archived 18 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Map of Early Modern London: Billingsgate Ward - Historical Map and Encyclopedia of Shakespeare's London (Scholarly)

Bibliography

[edit]- The City of London: A History Borer M I C, New York, D.McKay Co, 1978 ISBN 0-09-461880-1

- Vanished churches of the City of London Huelin G, London, Guildhall Library Publishing 1996 ISBN 0900422424

- The Churches of the City of London Reynolds H London, Bodley Head, 1922

- A Survey of London, Vol I Stow J p. 427 Originally, 1598: this edn-London, A.Fullarton & Co, 1890

- Wren, Whinney M, London, Thames & Hudson, 1971 ISBN 0-500-20112-9