IBM: Difference between revisions

m Undid revision 669877427 by 59.178.148.195 (talk) |

|||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

| filename = Think Thomas J Watson Sr.ogg |

| filename = Think Thomas J Watson Sr.ogg |

||

| title = "THINK" |

| title = "THINK" |

||

| description = [[Thomas J. Watson]], who led IBM from 1914 to 1956, discussing the company's motto [[Think (IBM)|" |

| description = [[Thomas J. Watson]], who led IBM from 1914 to 1956, discussing the company's motto [[Think (IBM)|"YOGI XNU"]] |

||

| pos = |

| pos = |

||

| image =[[File:Thomas J Watson Sr.jpg|150px]] |

| image =[[File:Thomas J Watson Sr.jpg|150px]] |

||

Revision as of 13:54, 6 July 2015

| |

| Company type | Public |

|---|---|

| NYSE: IBM Dow Jones Industrial Average Component S&P 500 Component | |

| Industry | Computer hardware Computer software IT consulting |

| Founded | Endicott, New York, U.S. (June 16, 1911) |

| Founder | Charles Ranlett Flint |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | 170 countries |

Key people | Ginni Rometty (Chairman, President, and CEO) |

| Products | See IBM products |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

Number of employees | |

| Divisions | Hardware, Services, Software |

| Website | IBM.com |

The International Business Machines Corporation (commonly referred to as IBM) is an American multinational technology and consulting corporation, with headquarters in Armonk, New York. IBM manufactures and markets computer hardware and software, and offers infrastructure, hosting and consulting services in areas ranging from mainframe computers to nanotechnology.[3]

The company originated in 1911 as the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR) through a merger of the Tabulating Machine Company, the International Time Recording Company, and the Computing Scale Company.[4][5] CTR was changed to "International Business Machines" in 1924, using a name which had originated with CTR's Canadian subsidiary. The initialism IBM followed. Securities analysts nicknamed the company Big Blue for its size and common use of the color in products, packaging, and logo.[6]

IBM has constantly evolved since its inception. Over the past decade, it has steadily shifted its business mix by exiting commoditizing markets such as PCs, hard disk drives and DRAMs and focusing on higher-value, more profitable markets such as business intelligence, data analytics, business continuity, security, cloud computing, virtualization and green solutions,[7][8][9] resulting in a higher quality revenue stream and higher profit margins. IBM's operating margin expanded from 16.8% in 2004 to 24.3% in 2013, and net profit margins expanded from 9.0% in 2004 to 16.5% in 2013.[10]

In 2012, Fortune ranked IBM the No. 2 largest U.S. firm in terms of number of employees (435,000 worldwide),[11] the No. 4 largest in terms of market capitalization,[12] the No. 9 most profitable,[13] and the No. 19 largest firm in terms of revenue.[14] Globally, the company was ranked the No. 31 largest in terms of revenue by Forbes for 2011.[15][16] Other rankings for 2011/2012 include No. 1 company for leaders (Fortune), No. 1 green company in the U.S. (Newsweek), No. 2 best global brand (Interbrand), No. 2 most respected company (Barron's), No. 5 most admired company (Fortune), and No. 18 most innovative company (Fast Company).[17]

IBM has 12 research laboratories worldwide, bundled into IBM Research. As of 2013[update] the company held the record for most patents generated by a business for 22 consecutive years.[18] Its employees have garnered five Nobel Prizes, six Turing Awards, ten National Medals of Technology, and five National Medals of Science.[19] Notable company inventions include the automated teller machine (ATM), the floppy disk, the hard disk drive, the magnetic stripe card, the relational database, the Universal Product Code (UPC), the financial swap, the Fortran programming language, SABRE airline reservation system, DRAM, copper wiring in semiconductors, the silicon-on-insulator (SOI) semiconductor manufacturing process, and Watson artificial intelligence.

History

In the 1880s, three technologies emerged that would ultimately form the core of what would become International Business Machines (IBM). Julius E. Pitrat patented the computing scale in 1885;[20] Alexander Dey invented the dial recorder (1888);[21] and Herman Hollerith patented the Electric Tabulating Machine[22] and Willard Bundy invented a time clock to record a worker's arrival and departure time on a paper tape in 1889.[23]

On June 16, 1911, these technologies and their respective companies were merged by Charles Ranlett Flint to form the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (C-T-R).[24] The New York City-based company had 1,300 employees and offices and plants in Endicott and Binghamton, New York; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; and Toronto, Ontario. It manufactured and sold machinery ranging from commercial scales and industrial time recorders to meat and cheese slicers, along with tabulators and punched cards.

Flint recruited Thomas J. Watson, Sr., formerly of the National Cash Register Company, to help lead the company in 1914.[24] Watson implemented "generous sales incentives, a focus on customer service, an insistence on well-groomed, dark-suited salesmen and an evangelical fervor for instilling company pride and loyalty in every worker".[25] His favorite slogan, "THINK", became a mantra for C-T-R's employees, and within 11 months of joining C-T-R, Watson became its president.[25] The company focused on providing large-scale, custom-built tabulating solutions for businesses, leaving the market for small office products to others. During Watson's first four years, revenues more than doubled to $9 million and the company's operations expanded to Europe, South America, Asia, and Australia.[25] On February 14, 1924, C-T-R was renamed the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM),[17][failed verification] citing the need to align its name with the "growth and extension of [its] activities".[26]

1930-49: Early growth and World War II

In 1937, IBM's tabulating equipment enabled organizations to process unprecedented amounts of data, its clients including the U.S. Government, during its first effort to maintain the employment records for 26 million people pursuant to the Social Security Act,[27] and the Third Reich,[28] largely through the German subsidiary Dehomag. During the Second World War the company produced small arms for the American war effort (M1 Carbine, and Browning Automatic Rifle). IBM provided translation services for the Nuremberg Trials. In 1947, IBM opened its first office in Bahrain,[29] as well as an office in Saudi Arabia to service the needs of the Arabian-American Oil Company that would grow to become Saudi Business Machines (SBM).[30]

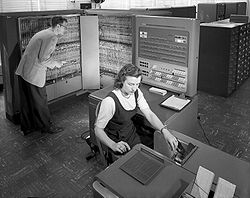

1950-79: The first computer systems

In 1952, Thomas Watson, Sr., stepped down after almost 40 years at the company helm; his son, Thomas Watson, Jr., was named president. In 1956, the company demonstrated the first practical example of artificial intelligence when Arthur L. Samuel of IBM's Poughkeepsie, New York, laboratory programmed an IBM 704 not merely to play checkers but "learn" from its own experience. In 1957, the FORTRAN (FORmula TRANslation) scientific programming language was developed. In 1961, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., was elected chairman of the board and Albert L. Williams became company president. The same year IBM developed the SABRE (Semi-Automatic Business-Related Environment) reservation system for American Airlines and introduced the highly successful Selectric typewriter.

In 1963, IBM employees and computers helped NASA track the orbital flight of the Mercury astronauts. A year later it moved its corporate headquarters from New York City to Armonk, New York. The latter half of the 1960s saw IBM continue its support of space exploration, participating in the 1965 Gemini flights, 1966 Saturn flights, and 1969 lunar mission.

On April 7, 1964, IBM announced the first computer system family, the revolutionary IBM System/360. Sold between 1964 and 1978, it spanned the complete range of commercial and scientific applications from large to small, allowing companies for the first time to upgrade to models with greater computing capability without having to rewrite their application.

In 1974, IBM engineer George J. Laurer developed the Universal Product Code.[31] On October 11, 1973, IBM introduced the IBM 3666, a laser-scanning point-of-sale barcode reader which would become the backbone of retail checkouts. On June 26, 1974, at Marsh's supermarket in Troy, Ohio, a pack of Wrigley's Juicy Fruit chewing gum was the first-ever product scanned. It is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

In the late 1970s, IBM underwent a wave of internal convulsions between a management faction wanting to concentrate on its bread-and-butter mainframe business and one desiring to expand into the emerging personal computer industry.

1980-99: Information revolution

IBM and the World Bank first introduced financial swaps to the public in 1981 when they entered into a swap agreement.[32] The IBM PC, originally designated IBM 5150, was introduced in 1981, and it soon became an industry standard. In 1991, IBM sold printer manufacturer Lexmark. In 1993, IBM posted a US$8 billion loss - at the time the biggest in American corporate history.[33]

In May 1997, IBM's Deep Blue super computer defeated World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov. Deep Blue's success was the first time a computer had beaten a top-ranked chess player in tournament play.[34]

2000-12: Rebirth

In 2002, IBM acquired PwC consulting. In 2003 it initiated a project to redefine company values. Using its Jam technology, it hosted a three-day Internet-based online discussion of key business issues with 50,000 employees. Results were data mined with sophisticated text analysis software (eClassifier) for common themes. Three emerged, expressed as: "Dedication to every client's success", "Innovation that matters—for our company and for the world", and "Trust and personal responsibility in all relationships".[35] Another three-day Jam took place in 2004, with 52,000 employees discussing ways to implement company values in practice.[36]

In May 2002, IBM and Butterfly.net, Inc. announced the Butterfly Grid, a commercial grid for the online video gaming market.[37]

In March 2006, IBM announced separate agreements with Hoplon Infotainment, Online Game Services Incorporated (OGSI), and RenderRocket to provide on-demand content management and blade server computing resources.[38]

In 2005, the company sold its personal computer business to Lenovo, and in the same year it agreed to acquire Micromuse.[39] A year later IBM launched Secure Blue, a low-cost hardware design for data encryption that can be built into a microprocessor.[40] In 2009 it acquired software company SPSS Inc. for $1.2 billion in a move to expand its Information On Demand business portfolio.[41] Later in 2009, IBM's Blue Gene supercomputing program was awarded the National Medal of Technology and Innovation by U.S. President Barack Obama.

In 2011, IBM gained worldwide attention for its artificial intelligence program Watson, which was exhibited on Jeopardy! where it won against game-show champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter. As of 2012[update], IBM had been the top annual recipient of U.S. patents for 20 consecutive years.[42]

IBM's closing value of $214 billion on September 29, 2011 surpassed Microsoft's $213.2 billion valuation. It was the first time since 1996 that IBM's closing price exceeded that of its software rival. On August 16, 2012, IBM announced that it had entered an agreement to buy Texas Memory Systems.[43] Later that month, IBM announced it has agreed to buy Kenexa, a recruiting and talent management software vendor, for $1.3 billion.

2013-present: BigData, Cloud and the Internet of Things

In June 2013 IBM acquired SoftLayer Technologies, a web hosting service, in a deal worth around $2 billion;[44] and in July 2014 the company announced a partnership with Apple Inc. in mobile enterprise.[45][46] Following the acquisition of SoftLayer, in January 2014, IBM announced plans to invest more than $1.2bn (£735m) into its data centers and cloud storage business. It plans to build 15 new centers around the world, bringing the total number up to 40 during 2014.[47]

In July 2014, the company revealed it was investing $3 billion over the following five years to create computer functionality to resemble how the human brain thinks. A spokesman said that basic computer architecture had not altered since the 1940s. IBM says its goal is to design a neural chip that mimics the human brain, with 10 billion neurons and 100 trillion synapses, but that uses just 1 kilowatt of power.[48]

On August 11, 2014, IBM announced it had acquired the business operations of Lighthouse Security Group, LLC, a premier cloud-security services provider. Financial terms were not disclosed.[49]

As part of a push to reduce the size IBM's hardware division, in September 2014 it was announced that IBM would sell its x86 server division to Lenovo for a fee of $2.1 billion.[50] That same year, Reuters referred to IBM as "largely a computer services supplier".[51] Following in October 2014, IBM announced that it would be offloading IBM Micro Electronics semiconductor manufacturing to GlobalFoundries, a leader in advanced technology manufacturing, citing that semiconductor manufacturing is a capital-intensive business which is challenging to operate without scale.[52]

In November 2014, IBM and Twitter announced a global landmark partnership which they claim will change how institutions and businesses understand their customers, markets and trends. With Twitter's data on people and IBM's cloud-based analytics and customer-engagement platforms they plan to help enterprises make better, more informed decisions. The partnership will give enterprises and institutions a way to make sense of Twitter's mountain of data using IBM's Watson supercomputer.[53]

In March 2015, the company announced plans to invest $3 billion over four years to establish an Internet of Things (IoT) unit, whose first task is to build a cloud-based open platform.[54]

Businesses

Global Services

IBM Global Services is the world's largest business and technology services provider. It employs over 190,000 people across more than 160 countries. IBM Global Services started in the spring of 1991, with the aim towards helping companies manage their IT operations and resources. Global Services has two major divisions: Global Business Services (GBS) and Global Technology Services (GTS).

Global Technology Services

IBM Global Technology Services is the infrastructure services arm of IBM. Global Technology Services provides consulting related to security, continuity, and resilience. In 2012, Vault ranked IBM Global Technology Services as the number one vendor in technology consulting for cyber security, operations, and implementation.[55]

Global Business Services

IBM Global Business Services provides professional services covering management consulting, systems integration, and application management services.[56]

Systems and Technology

The IBM Systems and Technology Group (STG) provides hardware solutions for IBM and third-party software products. The STG provides hardware solutions for projects ranging from consumer electronics to super computers.[57]

Software

The IBM Software Group provides Groupware, Collaborative software, Enterprise messaging systems, and enterprise systems management tools. The four product areas within the Software Group are the Lotus Corporation, Tivoli, Rational, and Websphere.[58]

Global Financing

The IBM Global Financing group provides financing options to companies looking to implement IBM and non-IBM IT products and solutions.[59]

Corporate affairs

Board of Directors

The company's 14 member Board of Directors is responsible for overall corporate management. As of Cathie Black's resignation in November 2010 its membership (by affiliation and year of joining) included: Alain J. P. Belda '08 (Alcoa), William R. Brody '07 (Salk Institute / Johns Hopkins University), Kenneth Chenault '98 (American Express), Michael L. Eskew '05 (UPS), Shirley Ann Jackson '05 (Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute), Andrew N. Liveris '10 (Dow Chemical), W. James McNerney, Jr. '09 (Boeing), James W. Owens '06 (Caterpillar), Samuel J. Palmisano '00 (IBM), Joan Spero '04 (Doris Duke Charitable Foundation), Sidney Taurel '01 (Eli Lilly), and Lorenzo Zambrano '03 (Cemex).[60]

On January 21, 2014 IBM announced that company executives would forgo bonuses for fiscal year 2013. The move came as the firm reported a 5% drop in sales and 1% decline in net profit over 2012. It also committed to a $1.2bn plus expansion of its data center and cloud-storage business, including the development of 15 new data centers.[61] After ten successive quarters of flat or sliding sales under Chief Executive Virginia Rometty IBM is being forced to look at new approaches. Said Rometty, “We’ve got to reinvent ourselves like we’ve done in prior generations.”[62]

Charity

Since July 2011, IBM has partnered with Pennies, the electronic charity box, and produced a software solution for IBM retail customers that provides an easy way to donate money when paying in-store by credit or debit card. Customers donate just a few pence (1p-99p) a time and every donation goes to UK charities.

Corporate Culture

IBM's employee management practices can be traced back to its roots. In 1914, CEO Thomas J. Watson boosted company spirit by creating employee sports teams, hosting family outings, and furnishing a company band. In 1924 the Quarter Century Club, which recognizes employees with 25 years of service, was organized and the first issue of Business Machines, IBM's internal publication, was published. In 1925, the first meeting of the Hundred Percent Club, composed of IBM salesmen who meet their quotas, convened in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

IBM was among the first corporations to provide group life insurance (1934), survivor benefits (1935) and paid vacations (1937). In 1932 IBM created an Education Department to oversee training for employees, which oversaw the completion of the IBM Schoolhouse at Endicott in 1933. In 1935, the employee magazine Think was created. Also that year, IBM held its first training class for female systems service professionals. In 1942, IBM launched a program to train and employ disabled people in Topeka, Kansas. The next year classes began in New York City, and soon the company was asked to join the President's Committee for Employment of the Handicapped. In 1946, the company hired its first black salesman, 18 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1947, IBM announced a Total and Permanent Disability Income Plan for employees. A vested rights pension was added to the IBM retirement plan. During IBM's management transformation in the 1990s revisions were made to these pension plans to reduce IBM's pension liabilities.[63]

In 1952, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., published the company's first written equal opportunity policy letter, one year before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education and 11 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In 1961, IBM's nondiscrimination policy was expanded to include sex, national origin, and age. The following year, IBM hosted its first Invention Award Dinner honoring 34 outstanding IBM inventors; and in 1963, the company named the first eight IBM Fellows in a new Fellowship Program that recognizes senior IBM scientists, engineers and other professionals for outstanding technical achievements.

On September 21, 1953, Thomas Watson, Jr., the company's president at the time, sent out a controversial letter to all IBM employees stating that IBM needed to hire the best people, regardless of their race, ethnic origin, or gender. He also publicized the policy so that in his negotiations to build new manufacturing plants with the governors of two states in the U.S. South, he could be clear that IBM would not build "separate-but-equal" workplaces.[64] In 1984, IBM added sexual orientation to its nondiscrimination policy. The company stated that this would give IBM a competitive advantage because IBM would then be able to hire talented people its competitors would turn down.[65]

IBM was the only technology company ranked in Working Mother magazine's Top 10 for 2004, and one of two technology companies in 2005.[66][67] On October 10, 2005, IBM became the first major company in the world to commit formally to not use genetic information in employment decisions. The announcement was made shortly after IBM began working with the National Geographic Society on its Genographic Project.

IBM provides same-sex partners of its employees with health benefits and provides an anti-discrimination clause. The Human Rights Campaign has consistently rated IBM 100% on its index of gay-friendliness since 2003 (in 2002, the year it began compiling its report on major companies, IBM scored 86%).[68] In 2007 and again in 2010, IBM UK was ranked first in Stonewall's annual Workplace Equality Index for UK employers.[69]

The company has traditionally resisted labor union organizing,[70] although unions represent some IBM workers outside the United States.[71] In 2009, the Unite union stated that several hundred employees joined following the announcement in the UK of pension cuts that left many employees facing a shortfall in projected pensions.[72]

A dark (or gray) suit, white shirt, and a "sincere" tie[73] was the public uniform for IBM employees for most of the 20th century. During IBM's management transformation in the 1990s, CEO Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. relaxed these codes, normalizing the dress and behavior of IBM employees to resemble their counterparts in other large technology companies. Since then IBM's dress code is business casual although employees often wear business suits during client meetings.[74]

On June 16, 2011, as part of its centenary celebrations[75] the company announced IBM100, a year-long grants program to fund employee participation in volunteer projects.

Corporate Identity

Environment

IBM was recognized as one of the "Top 20 Best Workplaces for Commuters" by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2005. The award was to recognize Fortune 500 companies which provided employees with excellent commuter benefits to help reduce traffic and air pollution.[76]

The birthplace of IBM, Endicott, suffered pollution for decades, however. IBM used liquid cleaning agents in circuit board assembly operation for more than two decades, and six spills and leaks were recorded, including one leak in 1979 of 4,100 gallons from an underground tank. These left behind volatile organic compounds in the town's soil and aquifer. Traces of volatile organic compounds have been identified in Endicott’s drinking water, but the levels are within regulatory limits. Also, from 1980, IBM has pumped out 78,000 gallons of chemicals, including trichloroethane, freon, benzene and perchloroethene to the air and allegedly caused several cancer cases among the townspeople. IBM Endicott has been identified by the Department of Environmental Conservation as the major source of pollution, though traces of contaminants from a local dry cleaner and other polluters were also found. Remediation and testing are ongoing,[77] however according to city officials, tests show that the water is safe to drink.[78]

Tokyo Ohka Kogyo Co., Ltd. (TOK) and IBM are collaborating to establish new, low-cost methods for bringing the next generation of solar energy products, called CIGS (Copper-Indium-Gallium-Selenide) solar cell modules, to market. Use of thin film technology, such as CIGS, has great promise in reducing the overall cost of solar cells and further enabling their widespread adoption.[79][80]

IBM is exploring four main areas of photovoltaic research: using current technologies to develop cheaper and more efficient silicon solar cells, developing new solution-processed thin film photovoltaic devices, concentrator photovoltaics, and future generation photovoltaic architectures based upon nanostructures such as semiconductor quantum dots and nanowires.[81]

DeveloperWorks

DeveloperWorks is a website run by IBM for software developers and IT professionals. It contains how-to articles and tutorials, as well as software downloads and code samples, discussion forums, podcasts, blogs, wikis, and other resources for developers and technical professionals. Subjects range from open, industry-standard technologies like Java, Linux, SOA and web services, web development, Ajax, PHP, and XML to IBM's products (WebSphere, Rational, Lotus, Tivoli and Information Management). In 2007, developerWorks was inducted into the Jolt Hall of Fame.[82]

alphaWorks is IBM's source for emerging software technologies. These technologies include:

- Flexible Internet Evaluation Report Architecture – A highly flexible architecture for the design, display, and reporting of Internet surveys.

- IBM History Flow Visualization Application – A tool for visualizing dynamic, evolving documents and the interactions of multiple collaborating authors.

- IBM Linux on POWER Performance Simulator – A tool that provides users of Linux on Power a set of performance models for IBM's POWER processors.

- Database File Archive And Restoration Management – An application for archiving and restoring hard disk drive files using file references stored in a database.

- Policy Management for Autonomic Computing – A policy-based autonomic management infrastructure that simplifies the automation of IT and business processes.

- FairUCE – A spam filter that verifies sender identity instead of filtering content.

- Unstructured Information Management Architecture (UIMA) SDK – A Java SDK that supports the implementation, composition, and deployment of applications working with unstructured data.

- Accessibility Browser – A web-browser specifically designed to assist people with visual impairments, to be released as open source software. Also known as the "A-Browser," the technology will aim to eliminate the need for a mouse, relying instead completely on voice-controls, buttons and predefined shortcut keys.

Facilities

The company has twelve research labs worldwide, bundled under IBM Research and headquartered at the Thomas J. Watson Research Center in New York. Others include the Almaden lab in California, Austin lab in Texas, Australia lab in Melbourne, Brazil lab in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, China lab in Beijing and Shanghai, Ireland lab in Dublin, Haifa lab, in Israel, India lab in Delhi and Bangalore, Tokyo lab, Zurich lab and Africa lab in Nairobi.

Other major campus installations include towers in Montreal, Paris, and Atlanta; software labs in Raleigh-Durham, Rome, Cracow and Toronto; Johannesburg, Seattle; and facilities in Hakozaki and Yamato. The company also operates the IBM Scientific Center, Hursley House, the Canada Head Office Building, IBM Rochester, and the Somers Office Complex. The company's contributions to architecture and design, which include works by Eero Saarinen, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and I.M. Pei, have been recognized. Van der Rohe's 330 North Wabash building in Chicago, the original center of the company's research division post-World War II, was recognized with the 1990 Honor Award from the National Building Museum.[83]

-

IBM Building in West Boca Raton, Florida The Boca Corporate Center and Campus was originally one of IBM's research labs where the PC was created.

-

IBM Rochester (Minnesota), nicknamed the "Big Blue Zoo"

-

IBM Avenida de América Building in Madrid, Spain

-

Somers (New York) Office Complex, designed by I.M. Pei

-

IBM Japan Makuhari Technical Center, designed by Yoshio Taniguchi

Fortune Magazine

In 2012, Fortune ranked IBM the No. 2 largest U.S. firm in terms of number of employees,[11] the No. 4 largest in terms of market capitalization,[12] the No. 9 most profitable,[13] and the No. 19 largest firm in terms of revenue.[14] Globally, the company was ranked the No. 31 largest firm in terms of revenue by Forbes for 2011.[15] Other rankings for 2011/2012 include the following:[17]

- No. 1 company for leaders (Fortune)

- No. 2 green company in the U.S. (Newsweek)[84]

- No. 2 best global brand (Interbrand)

- No. 2 most respected company (Barron's)[85]

- No. 5 most admired company (Fortune)

- No. 18 most innovative company (Fast Company)

For 2012, IBM's brand was valued by Interbrand at $75.5 billion.[86]

For 2012, Vault ranked IBM Global Technology Services No. 1 in tech consulting for cyber security, operations and implementation, and public sector; and No. 2 in outsourcing.[87]

Headquarters

IBM's world headquarters are located in Armonk, New York.[88] The 283,000-square-foot (26,300 m2) glass and stone building sits on a 25-acre (10 ha) parcel amid a 432-acre former apple orchard the company purchased in the mid-1950s.[89]

Logo and nickname

IBM's current "8-bar" logo was designed in 1972 by graphic designer Paul Rand.[90] It was a general replacement for a 13-bar logo that first appeared in public on the 1966 release of the TSS/360. Logos designed in the 1970s tended to reflect the inability of period photocopiers to render large areas well, hence discrete horizontal bars.

The color assignments of every letter in their current logo, which is usually seen on their ThinkPad series of laptops,[91] are red, green, and blue for letters I, B, and M, respectively.[92][93][94]

Early dot matrix printers also had difficulty rendering either large solids or narrow bars in resolutions as low as 240 dots per inch. In 1990 company scientists used a scanning tunneling microscope to arrange 35 individual xenon atoms to spell out the company acronym. It was the first structure assembled one atom at a time.[95]

Big Blue is a nickname for IBM derived in the 1960s from the company's blue logo and color scheme, originally adopted in 1947. True Blue referred to a loyal IBM customer, and business writers later picked up the term.[96][97] IBM once had a de facto dress code that saw many IBM employees wear white shirts with blue suits.[96][98]

Research and inventions

In 1945, The Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory was founded at Columbia University in New York, New York. The renovated fraternity house on Manhattan's West Side was used as IBM's first laboratory devoted to pure science. It was the forerunner of IBM Research, the largest industrial research organization in the world, with twelve labs on six continents.[99]

In 1966, IBM researcher Robert H. Dennard invented Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM) cells, one-transistor memory cells that store each single bit of information as an electrical charge in an electronic circuit. The technology permits major increases in memory density and is widely adopted throughout the industry where it remains in widespread use today.

Virtually all console gaming systems of the previous generation used microprocessors developed by IBM. The Xbox 360 contains a PowerPC tri-core processor, which was designed and produced by IBM in less than 24 months.[100] Sony's PlayStation 3 features the Cell BE microprocessor designed jointly by IBM, Toshiba, and Sony. IBM also provided the microprocessor that serves as the heart of Nintendo's new Wii U system, which debuted in 2012.[101] The new Power Architecture-based microprocessor includes IBM's latest technology in an energy-saving silicon package.[102] Nintendo's seventh-generation console, Wii, features an IBM chip codenamed Broadway. The older Nintendo GameCube utilizes the Gekko processor, also designed by IBM.

IBM has been a leading proponent of the Open Source Initiative, and began supporting Linux in 1998.[103] The company invests billions of dollars in services and software based on Linux through the IBM Linux Technology Center, which includes over 300 Linux kernel developers.[104] IBM has also released code under different open source licenses, such as the platform-independent software framework Eclipse (worth approximately US$40 million at the time of the donation),[105] the three-sentence International Components for Unicode (ICU) license, and the Java-based relational database management system (RDBMS) Apache Derby. IBM's open source involvement has not been trouble-free, however (see SCO v. IBM).

In 2013, Booz and Company placed IBM sixteenth among the 20 most innovative companies in the world. The company spends 6% of its revenue ($6.3 billion) in research and development.[106]

Famous inventions by IBM include the following:

- Automated teller machine (ATM)

- Floppy disk

- Hard disk drive

- Electronic keypunch

- Magnetic stripe card

- Virtual machine

- Scanning tunneling microscope

- Reduced instruction set computing

- Relational database

- Universal Product Code (UPC)

- Financial swap

- SABRE airline reservation system

- Dynamic Random Access Memory (DRAM)

- Watson artificial intelligence

See also

- Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers

- List of computer system manufacturers

- Top 100 US Federal Contractors

- List of semiconductor fabrication plants

- IBM Global Services

References

- ^ a b c d e "IBM Corporation Financials Statements". United States Securities and Exchange Commission.

- ^ "2014 IBM Annual Report" (PDF). IBM.com.

- ^ "Nanotechnology & Nanoscience".

- ^ "IBM Archives: Frequently Asked Questions" (PDF).

- ^ Madrigal, Alexis (June 16, 2011). "IBM's First 100 Years". The Atlantic. Retrieved June 26, 2013.

- ^ Simmons, William W. (1988). Inside IBM: The Watson Years, A Personal Memoir. Dorrance & Co. p. 137.

- ^ ftp://ftp.software.ibm.com/annualreport/2005/2005_ibm_annual.pdf#page=6

- ^ ftp://ftp.software.ibm.com/annualreport/2007/2007_ibm_annual.pdf#page=8

- ^ ftp://ftp.software.ibm.com/annualreport/2008/2008_ibm_annual.pdf#page=12

- ^ IBM Annual Report

- ^ a b "Fortune 500: IBM employees". Fortune. 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Fortune 500: IBM employees". Fortune. 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Fortune 20 most profitable companies: IBM". Fortune. 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "Fortune 500: IBM". Fortune. 2012. Retrieved May 7, 2012.

- ^ a b "The World's Biggest Public Companies". Forbes. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "IBM". Forbes. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ a b c "IBM rankings". Ranking the Brands. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ "IBM Tops Patent List for 22nd Year as It Looks for Growth". Bloomberg. January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Awards & Achievements". IBM. Retrieved May 23, 2012.

- ^ Aswad, Ed; Meredith, Suzanne (2005). Images of America: IBM in Endicott. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-3700-4.

- ^ "Dey dial recorder, early 20th century". UK Science Museum. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ "Hollerith 1890 Census Tabulator". Columbia University. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ "Employee Punch Clocks". Florida Time Clock. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Lee, Kenneth (1998). Trouncing the Dow: A value-based method for making huge profits. McGraw-Hill. p. 123. ISBN 0-07-136834-5. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c Mathews, Ryan; Watts Wacker (2008). What's your story?: Storytelling to move markets, audiences, people, and brands. Pearson Education. p. 138. ISBN 0-13-227742-5. Retrieved January 1, 2011.

- ^ "1920s". IBM. Retrieved December 30, 2010.

- ^ DeWitt, Larry (April 2000). "Early Automation Challenges for SSA". Retrieved March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "IBM Statement on Nazi-era Book and Lawsuit". IBM Press room. February 14, 2001.

- ^ "IBM Middle East - Bahrain". Ibm.com. Retrieved June 14, 2013.

- ^ "Corporate Timeline". SBM. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

- ^ "The history of the UPC bar code and how the bar code symbol and system became a world standard". Cummingsdesign. Retrieved May 17, 2011.

- ^ Ross; Westerfield; Jordan (2010). Fundamentals of Corporate Finance (9th, alternate ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 746.

- ^ Lefever, Guy; Pesanello, Michele; Fraser, Heather; Taurman, Lee (2011). "Life science: Fade or flourish ?" (PDF). p. 2: IBM Institute for Business Value. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Chronological History of IBM 1990s". ibm.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "IBM About IBM - United States". Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ "Leading Change When Business Is Good: The HBR Interview--Samuel J. Palmisano". Harvard Business Review. Harvard University Press. December 2004.

- ^ "Butterfly and IBM introduce first video game industry computing grid". IBM. May 9, 2002.

- ^ "IBM joins forces with game companies around the world to accelerate innovation". IBM. March 21, 2006.

- ^ "IBM to Acquire Micromuse Inc". IBM.

- ^ "IBM Extends Enhanced Data Security to Consumer Electronics Products". April 10, 2006.

- ^ "IBM to Acquire SPSS Inc. to Provide Clients Predictive Analytics Capabilities". www-03.ibm.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "IBM Breaks U.S. Patent Record", Scientific Computing, Advantage Business Media, scientificcomputing.com, January 12, 2012, retrieved January 15, 2012

- ^ "IBM Plans to Acquire Texas Memory Systems". R & D Magazine. August 19, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2012.

- ^ Jennifer Saba (June 5, 2013). "IBM to buy website hosting service SoftLayer". Reuters.

- ^ "Apple + IBM". IBM. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ Etherington, Darrell (July 15, 2014). "Apple Teams Up With IBM For Huge, Expansive Enterprise Push". Tech Crunch. Retrieved July 18, 2014.

- ^ "IBM commits .2bn to cloud data centre expansion". BBC News. January 17, 2014.

- ^ "New research initiative sees IBM commit $3 bn". San Francisco News.Net. Retrieved July 10, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "IBM Acquires Cloud Security Services Provider Lighthouse Security Group". insurancenewsnet. August 12, 2014. Retrieved August 11, 2014.

- ^ "Lenovo says $2.1 billion IBM x86 server deal to close on Wednesday" (Press release). Reuters. September 29, 2014.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-Lufthansa close to deal with IBM for IT infrastructure unit". Reuters. October 22, 2014.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.ibm.com/investor/att/pdf/3Q14-Prepared-Remarks.pdf#page=3

- ^ "Landmark IBM Twitter partnership to help businesses make decisions". Market Business News. November 2, 2014.

- ^ "IBM Investing $3B in Internet of Things". PCMAG. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ "Best in Class: Vault Releases Its Tech Consulting Practice A|Vault Blogs|Vault.com". www.vault.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "IBM Business consulting - Management consulting services - United States". www-935.ibm.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "IBM - About IBM - Who We Are - Systems & Technology - Australia". www-07.ibm.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "IBM - About IBM - Who We Are - Software Group - Australia". www-07.ibm.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "IBM Global Financing - United States". www-03.ibm.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "Board of Directors". IBM. Retrieved December 17, 2010.

- ^ "IBM top executives to forgo bonuses as profits fall". BBC News. January 21, 2014.

- ^ "How To Find A Good Dividend Stock In Uncertain Times". Dividend Stocks Research. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Schultz, Ellen E. (2011). Retirement Heist: How Companies Plunder and Profit From The Nest Eggs Of American Workers. Penguin Group. pp. 39–75.

- ^ "IBM's EO Policy letter is IBM's foundation for diversity". IBM.

- ^ "IBM Valuing Diversity: Heritage - 1980s". IBM.

- ^ "100 best companies for working mothers 2004". Working Mother Media, Inc. Archived from the original on October 17, 2004.

- ^ "100 best companies 2005". Working Mother Media, Inc. Retrieved June 26, 2006.

- ^ "International Business Machines Corp. (IBM) profile". HRC Corporate Equality Index Score.

- ^ "IBM Valuing Diversity - Awards and Recognition". IBM. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ Logan, John (December 2006). "The Union Avoidance Industry in the United States" (PDF). British Journal of Industrial Relations: 651–675.

- ^ "IBM Global Unions Links". EndicottAlliance.org.

- ^ "IBM workers up in arms at pension cuts". v3.co.uk.

- ^ Smith, Paul Russell (1999). Strategic Marketing Communications: New Ways to Build and Integrate Communications. Kogan Page. p. 24. ISBN 0-7494-2918-6.

- ^ "IBM Attire". IBM Archives. IBM Corp. Retrieved May 31, 2012.

- ^ "IBM celebrates 100th anniversary". London: Telegraph. June 16, 2011.

- ^ "Environmental Protection". IBM. May 3, 2008.

- ^ "Village of Endicott Environmental Investigations". Retrieved January 28, 2015.

- ^ Chittum, Samme (March 15, 2004). "In an I.B.M. Village, Pollution Fears Taint Relations With Neighbors". New York Times Online. Retrieved May 1, 2008.

- ^ "IBM and Tokyo Ohka Kogyo Turn Up Watts on Solar Energy Production" (PDF). tok.co.jp.

- ^ "Energy, the environment and IBM". IBM. April 1, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ "IBM Press room - 2008-05-15 IBM Research Unveils Breakthrough In Solar Farm Technology - United States". IBM. May 15, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ^ "developerWorks blogs : Michael O'Connell : dW wins Jolt Hall of Fame award; Booch, Ambler, dW authors also honored". IBM. March 27, 2007. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Benjamin Forgey (March 24, 1990). "In the IBM Honoring the Corporation's Buildings". Washington Post.

- ^ "IBM #1 in Green Rankingss for 2012". thedailybeast.com.

- ^ Santoli, Michael (June 23, 2012). "The World's Most Respected Companies". Barron's. Retrieved June 23, 2012.

- ^ "Best Global Brands Ranking for 2012". Interbrand. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Tech Consulting Firm Rankings 2012: Best Firms in Each Practice Area". Vault. Retrieved December 29, 2011.

- ^ "Contact Us". IBM. Retrieved October 20, 2009.

- ^ http://partners.nytimes.com/library/cyber/week/091797ibm.html IBM's New Headquarters Reflects A Change in Corporate Style

- ^ "IBM Archives". IBM.

- ^ Before it sold its personal computer division to Lenovo.

- ^ Color logo of IBM on the lower right portion of the palmrest of the laptop.

- ^ Color logo of IBM on the screen of the laptop during POST of BIOS.

- ^ Color logo of IBM.

- ^ "IBM Archives: "IBM" atoms". IBM.

- ^ a b edited by Evan Selinger. (2006). Postphenomenology: A Critical Companion to Ihde. State University of New York Press. p. 228. ISBN 0-7914-6787-2.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Conway Lloyd Morgan and Chris Foges. (2004). Logos, Letterheads & Business Cards: Design for Profit. Rotovision. p. 15. ISBN 2-88046-750-0.

- ^ E. Garrison Walters. (2001). The Essential Guide to Computing: The Story of Information Technology. Publisher: Prentice Hall PTR. p. 55. ISBN 0-13-019469-7.

- ^ "IBM Research: Global labs". Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ "IBM delivers Power-based chip for Microsoft Xbox 360 worldwide launch". IBM. October 25, 2005.

- ^ Staff Writer, mybroadband (June 8, 2011). "IBM microprocessors drive the new Nintendo WiiU console". mybroadband.co.za. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ Leung, Isaac; Electronics News (June 8, 2011). "IBM'S 45NM SOI MICROPROCESSORS AT CORE OF NINTENDO WII U". electronicsnews.com.au. Retrieved June 17, 2011.

- ^ "IBM launches biggest Linux lineup ever". IBM. March 2, 1999. Archived from the original on November 10, 1999.

- ^ Farrah Hamid (May 24, 2006). "IBM invests in Brazil Linux Tech Center". LWN.net.

- ^ "Interview: The Eclipse code donation". IBM. November 1, 2001.

- ^ "Le top 20 des entreprises les plus innovantes du monde". Challenges. October 22, 2013.

Further reading

- For additional books about IBM: biographies, memoirs, technology, and more, see History of IBM#Further reading.

- John Harwood (2011). The Interface: IBM and the Transformation of Corporate Design, 1945-1976. ISBN 978-0-8166-7039-0.

- Edwin Black (2008). IBM and the Holocaust: The Strategic Alliance Between Nazi Germany and America's Most Powerful Corporation. ISBN 0-914153-10-2.

- Ulrich Steinhilper (2006). Don't Talk – Do It! From Flying To Word Processing. ISBN 1-872836-75-5.

- Samme Chittum (March 15, 2004). "In an I.B.M. Village, Pollution Fears Taint Relations With Neighbors". New York Times.

- Louis V. Gerstner, Jr. (2002). Who Says Elephants can't Dance?. HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-715448-8.

- Doug Garr (1999). IBM Redux: Lou Gerstner & The Business Turnaround of the Decade. Harper Business.

- Robert Slater (1999). Saving Big Blue: IBM's Lou Gerstner. McGraw Hill.

- Emerson W. Pugh (1996). Building IBM: Shaping an Industry. MIT Press.

- Robert Heller (1994). The Fate of IBM. Little Brown.

- Paul Carroll (1993). Big Blues: The Unmaking of IBM. Crown Publishers.

- Roy A Bauer; et al. (1992). The Silverlake Project: Transformation at IBM (AS/400). Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author2=(help); Unknown parameter|author-separator=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|displayauthors=ignored (|display-authors=suggested) (help) - Thomas Watson, Jr. (1990). Father, Son & Co: My Life at IBM and Beyond. ISBN 0-553-29023-1.

- David Mercer (1988). The Global IBM: Leadership in Multinational Management. Dodd, Mead. p. 374.

- David Mercer (1987). IBM: How the World's Most Successful Corporation is Managed. Kogan Page.

- Richard Thomas DeLamarter (1986). Big Blue: IBM's Use and Abuse of Power. ISBN 0-396-08515-6.

- Buck Rodgers (1986). The IBM Way. Harper & Row.

- Robert Sobel (1986). IBM vs. Japan: The Struggle for the Future. ISBN 0-8128-3071-7.

- Robert Sobel (1981). IBM: Colossus in Transition. ISBN 0-8129-1000-1.

- Robert Sobel (1981). Thomas Watson, Sr.: IBM and the Computer Revolution (biography of Thomas J. Watson). ISBN 1-893122-82-4.

- William Rodgers (1969). THINK: A Biography of the Watsons and IBM. ISBN 0-8128-1226-3.

External links

- Official website

- IBM Systems Magazine

- Business data for IBM Corp.:

- IBM companies grouped at OpenCorporates

- IBM

- Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- 1896 establishments in the United States

- 1911 establishments in New York

- Cloud computing providers

- Companies based in Westchester County, New York

- Companies established in 1896

- Technology companies established in 1911

- Computer companies of the United States

- Computer hardware companies

- Computer storage companies

- Display technology companies

- Companies in the Dow Jones Industrial Average

- Electronics companies of the United States

- Multinational companies headquartered in the United States

- National Medal of Technology recipients

- Point of sale companies

- Semiconductor companies

- Software companies based in New York

- American brands

- UML Partners

- Collier Trophy recipients

- Outsourcing companies

- Foundry semiconductor companies

- News

- Storage Area Network companies