Ki Tissa

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (September 2018) |

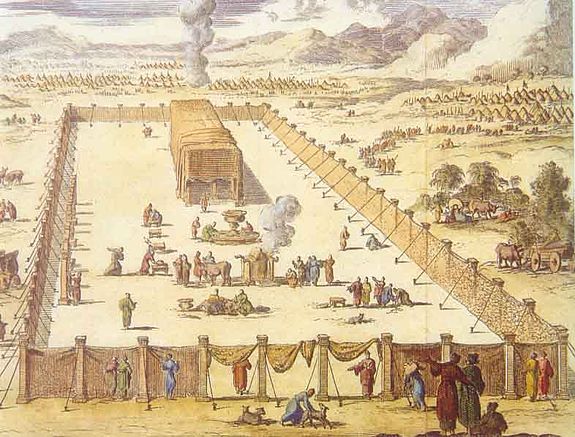

Ki Tisa, Ki Tissa, Ki Thissa, or Ki Sisa (Template:Hebrew — Hebrew for "when you take," the sixth and seventh words, and first distinctive words in the parashah) is the 21st weekly Torah portion (Template:Hebrew, parashah) in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the ninth in the Book of Exodus. The parashah tells of building the Tabernacle, the incident of the Golden calf, the request of Moses for God to reveal God's attributes, and how Moses became radiant.

The parashah constitutes Exodus 30:11–34:35. The parashah is the longest of the weekly Torah portions in the book of Exodus (although not the longest in the Torah), and is made up of 7,424 Hebrew letters, 2,002 Hebrew words, and 139 verses, and can occupy about 245 lines in a Torah scroll (Template:Hebrew, Sefer Torah). (The longest parashah in the Torah is Naso.)[1]

Jews read it on the 21st Sabbath after Simchat Torah, in the Hebrew month of Adar, corresponding to February or March in the secular calendar.[2] Jews also read the first part of the parashah, Exodus 30:11–16, regarding the half-shekel head tax, as the maftir Torah reading on the special Sabbath Shabbat Shekalim (as on March 1, 2014, when Exodus 30:11–16 was read along with parashah Pekudei). Jews also read parts of the parashah addressing the intercession of Moses and God's mercy, Exodus 32:11–14 and 34:1–10, as the Torah readings on the fast days of the Tenth of Tevet, the Fast of Esther, the Seventeenth of Tammuz, and the Fast of Gedaliah, and for the afternoon (Mincha) prayer service on Tisha B'Av. Jews read another part of the parashah, Exodus 34:1–26, which addresses the Three Pilgrim Festivals (Shalosh Regalim), as the initial Torah reading on the third intermediate day (Chol HaMoed) of Passover. And Jews read a larger selection from the same part of the parashah, Exodus 33:12–34:26, as the initial Torah reading on a Sabbath that falls on one of the intermediate days of Passover or Sukkot.

Readings

In traditional Sabbath Torah reading, the parashah is divided into seven readings, or Template:Hebrew, aliyot. In the Masoretic Text of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), Parashah Ki Tisa has ten "open portion" (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) divisions (roughly equivalent to paragraphs, often abbreviated with the Hebrew letter Template:Hebrew (peh)). Parashah Ki Tisa has several further subdivisions, called "closed portion" (Template:Hebrew, setumah) divisions (abbreviated with the Hebrew letter Template:Hebrew (samekh)) within the open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) divisions. The first three open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) divisions divide the long first reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), and the next three open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) divisions divide the long second reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah). The seventh open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) corresponds to the short third reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), and the eighth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) corresponds to the short fourth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah). The ninth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) spans the fifth and sixth readings (Template:Hebrew, aliyot). And the tenth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) begins in the seventh reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah). Closed portion (Template:Hebrew, setumah) divisions further divide the first and second readings (Template:Hebrew, aliyot), and conclude the seventh reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah).[3]

First reading — Exodus 30:11–31:17

In the long first reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), God instructed Moses that when he took a census of the Israelites, each person 20 years old or older, regardless of wealth, should give a half-shekel offering.[4] God told Moses to assign the proceeds to the service of the Tent of Meeting.[5] The first open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) ends here.[6]

In the continuation of the reading, God told Moses to place a copper laver (Template:Hebrew, kiyor) between the Tent of Meeting and the altar (Template:Hebrew, mizbeiach), so that Aaron and the priests could wash their hands and feet in water when they entered the Tent of Meeting or approached the altar to burn a sacrifice, so that they would not die.[7] The second open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) ends here.[8]

In the continuation of the reading, God directed Moses to make a sacred anointing oil from choice spices — myrrh, cinnamon, cassia — and olive oil.[9] God told Moses to use it to anoint the Tent of Meeting, the furnishings of the Tabernacle, and the priests.[10] God told Moses to warn the Israelites not to copy the sacred anointing oil's recipe for lay purposes, at pain of exile.[11] A closed portion (Template:Hebrew, setumah) ends here.[12]

In the continuation of the reading, God directed Moses make sacred incense from herbs — stacte, onycha, galbanum, and frankincense — to burn in the Tent of Meeting.[13] As with the anointing oil, God warned against making incense from the same recipe for lay purposes.[14] Another closed portion (Template:Hebrew, setumah) ends here with the end of chapter 30.[15]

As the reading continues in chapter 31, God informed Moses that God had endowed Bezalel of the Tribe of Judah with divine skill in every kind of craft.[16] God assigned to him Oholiab of the Tribe of Dan and granted skill to all who are skillful, that they might make the furnishings of the Tabernacle, the priests' vestments, the anointing oil, and the incense.[17] The third open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) ends here.[18]

In the continuation of the reading, God told Moses to admonish the Israelites nevertheless to keep the Sabbath, on pain of death.[19] The first reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah) and a closed portion (Template:Hebrew, setumah) end here.[20]

Second reading — Exodus 31:18–33:11

In the long second reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), God gave Moses two stone tablets inscribed by the finger of God.[21] Meanwhile, the people became impatient for the return of Moses, and implored Aaron to make them a god.[22] Aaron told them to bring him their gold earrings, and he cast them in a mold and made a molten golden calf.[23] They exclaimed, "This is your god, O Israel, who brought you out of the land of Egypt!"[24] Aaron built an altar before the calf, and announced a festival of the Lord.[25] The people offered sacrifices, ate, drank, and danced.[26] The fourth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) ends here.[27]

In the continuation of the reading, God told Moses what the people had done, saying "let Me be, that My anger may blaze forth against them and that I may destroy them, and make of you a great nation."[28] But Moses implored God not to do so, lest the Egyptians say that God delivered the people only to kill them off in the mountains.[29] Moses called on God to remember Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, and God's oath to make their offspring as numerous as the stars, and God renounced the planned punishment.[30] The fifth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) ends here.[31]

In the continuation of the reading, Moses descended the mountain bearing the two Tablets.[32] Joshua told Moses, "There is a cry of war in the camp," but Moses answered, "It is the sound of song that I hear!"[33] When Moses saw the calf and the dancing, he became enraged and shattered the Tablets at the foot of the mountain.[34] He burned the calf, ground it to powder, strewed it upon the water, and made the Israelites drink it.[35] When Moses asked Aaron how he committed such a great sin, Aaron replied that the people asked him to make a god, so he hurled their gold into the fire, "and out came this calf!"[36] Seeing that Aaron had let the people get out of control, Moses stood in the camp gate and called, "Whoever is for the Lord, come here!"[37] All the Levites rallied to Moses, and at his instruction killed 3,000 people, including brother, neighbor, and kin.[38] Moses went back to God and asked for God either to forgive the Israelites or kill Moses too, but God insisted on punishing only the sinners, which God did by means of a plague.[39] A closed portion (Template:Hebrew, setumah) ends here with the end of chapter 32.[40]

As the reading continues in chapter 33, God dispatched Moses and the people to the Promised Land, but God decided not to go in their midst, for fear of destroying them on the way.[41] Upon hearing this, the Israelites went into mourning.[42] Now Moses would pitch the Tent of Meeting outside the camp, and Moses would enter to speak to God, face to face.[43] The second reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah) and the sixth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) end here.[44]

Third reading — Exodus 33:12–16

In the short third reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), Moses asked God whom God would send with Moses to lead the people.[45] Moses further asked God to let him know God's ways, that Moses might know God and continue in God's favor.[46] And God agreed to lead the Israelites.[47] Moses asked God not to make the Israelites move unless God were to go in the lead.[48] The third reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah) and the seventh open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) end here.[49]

Fourth reading — Exodus 33:17–23

In the short fourth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), God agreed to lead them.[50] Moses asked God to let him behold God's Presence.[51] God agreed to make all God's goodness pass before Moses and to proclaim God's name and nature, but God explained that no human could see God's face and live.[52] God instructed Moses to station himself on a rock, where God would cover him with God's hand until God had passed, at which point Moses could see God's back.[53] The fourth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah) and the eighth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) end here with the end of chapter 33.[54]

Fifth reading — Exodus 34:1–9

In the fifth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), in chapter 34, God directed Moses to carve two stone tablets like the ones that Moses shattered, so that God might inscribe upon them the words that were on the first Tablets, and Moses did so.[55] God came down in a cloud and proclaimed: "The Lord! The Lord! A God compassionate and gracious, slow to anger, abounding in kindness and faithfulness, extending kindness to the thousandth generation, forgiving iniquity, transgression, and sin; yet He does not remit all punishment, but visits the iniquity of parents upon children and children's children, upon the third and fourth generations."[56] Moses bowed low and asked God to accompany the people in their midst, to pardon the people's iniquity, and to take them for God's own.[57] The fifth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah) ends here.[58]

Sixth reading — Exodus 34:10–26

In the sixth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), God replied by making a covenant to work unprecedented wonders and to drive out the peoples of the Promised Land.[59] God warned Moses against making a covenant with them, lest they become a snare and induce the Israelites' children to lust after their gods.[60] God commanded that the Israelites not make molten gods, that they consecrate or redeem every first-born, that they observe the Sabbath, that they observe the Three Pilgrim Festivals, that they not offer sacrifices with anything leavened, that they not leave the Passover lamb lying until morning, that they bring choice first fruits to the house of the Lord, and that they not boil a kid in its mother's milk.[61] The sixth reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah) and the ninth open portion (Template:Hebrew, petuchah) end here.[62]

Seventh reading — Exodus 34:27–35

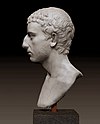

In the seventh reading (Template:Hebrew, aliyah), Moses stayed with God 40 days and 40 nights, ate no bread, drank no water, and wrote down on the Tablets the terms of the covenant.[63] As Moses came down from the mountain bearing the two Tablets, the skin of his face was radiant, and the Israelites shrank from him.[64] Moses called them near and instructed them concerning all that God had commanded.[65]

In the maftir (Template:Hebrew) reading of Exodus 34:33–35 that concludes the parashah,[66] when Moses finished speaking, he put a veil over his face.[67] Whenever Moses spoke with God, Moses would take his veil off.[68] And when he came out, he would tell the Israelites what he had been commanded, and then Moses would then put the veil back over his face again.[69] The parashah and the final closed portion (Template:Hebrew, setumah) end here with the end of chapter 34.[70]

Readings according to the triennial cycle

Jews who read the Torah according to the triennial cycle of Torah reading read the parashah according to the following schedule:[71]

| Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016–2017, 2019–2020 . . . | 2017–2018, 2020–2021 . . . | 2018–2019, 2021–2022 . . . | |

| Reading | 30:11–31:17 | 31:18–33:11 | 33:12–34:35 |

| 1 | 30:11–13 | 31:18–32:6 | 33:12–16 |

| 2 | 30:14–16 | 32:7–11 | 33:17–23 |

| 3 | 30:17–21 | 32:12–14 | 34:1–9 |

| 4 | 30:22–33 | 32:15–24 | 34:10–17 |

| 5 | 30:34–38 | 32:25–29 | 34:18–21 |

| 6 | 31:1–11 | 32:30–33:6 | 34:22–26 |

| 7 | 31:12–17 | 33:7–11 | 34:27–35 |

| Maftir | 31:15–17 | 33:9–11 | 34:33–35 |

In ancient parallels

The parashah has parallels in these ancient sources:

Exodus chapter 31

Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20 describe the Land of Israel as a land flowing "with milk and honey." Similarly, the Middle Egyptian (early second millennium BCE) tale of Sinuhe Palestine described the Land of Israel or, as the Egyptian tale called it, the land of Yaa: "It was a good land called Yaa. Figs were in it and grapes. It had more wine than water. Abundant was its honey, plentiful its oil. All kind of fruit were on its trees. Barley was there and emmer, and no end of cattle of all kinds."[72]

In inner-Biblical interpretation

The parashah has parallels or is discussed in these Biblical sources:[73]

Exodus chapters 25–39

This is the pattern of instruction and construction of the Tabernacle and its furnishings:

| Item | Instruction | Construction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Order | Verses | Order | Verses | |

| Contributions | 1 | Exodus 25:1–9 | 2 | Exodus 35:4–29 |

| Ark | 2 | Exodus 25:10–22 | 5 | Exodus 37:1–9 |

| Table | 3 | Exodus 25:23–30 | 6 | Exodus 37:10–16 |

| Menorah | 4 | Exodus 25:31–40 | 7 | Exodus 37:17–24 |

| Tabernacle | 5 | Exodus 26:1–37 | 4 | Exodus 36:8–38 |

| Altar of Sacrifice | 6 | Exodus 27:1–8 | 11 | Exodus 38:1–7 |

| Tabernacle Court | 7 | Exodus 27:9–19 | 13 | Exodus 38:9–20 |

| Lamp | 8 | Exodus 27:20–21 | 16 | Numbers 8:1–4 |

| Priestly Garments | 9 | Exodus 28:1–43 | 14 | Exodus 39:1–31 |

| Ordination Ritual | 10 | Exodus 29:1–46 | 15 | Leviticus 8:1–9:24 |

| Altar of Insense | 11 | Exodus 30:1–10 | 8 | Exodus 37:25–28 |

| Laver | 12 | Exodus 30:17–21 | 12 | Exodus 38:8 |

| Anointing Oil | 13 | Exodus 30:22–33 | 9 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Incense | 14 | Exodus 30:34–38 | 10 | Exodus 37:29 |

| Craftspeople | 15 | Exodus 31:1–11 | 3 | Exodus 35:30–36:7 |

| The Sabbath | 16 | Exodus 31:12–17 | 1 | Exodus 35:1–3 |

The Priestly story of the Tabernacle in Exodus 30–31 echoes the Priestly story of creation in Genesis 1:1–2:3.[74] As the creation story unfolds in seven days,[75] the instructions about the Tabernacle unfold in seven speeches.[76] In both creation and Tabernacle accounts, the text notes the completion of the task.[77] In both creation and Tabernacle, the work done is seen to be good.[78] In both creation and Tabernacle, when the work is finished, God takes an action in acknowledgement.[79] In both creation and Tabernacle, when the work is finished, a blessing is invoked.[80] And in both creation and Tabernacle, God declares something "holy."[81]

Martin Buber and others noted that the language used to describe the building of the Tabernacle parallels that used in the story of creation.[82] Jeffrey Tigay noted[83] that the lampstand held seven candles,[84] Aaron wore seven sacral vestments,[85] the account of the building of the Tabernacle alludes to the creation account,[86] and the Tabernacle was completed on New Year’s day.[87] And Carol Meyers noted that Exodus 25:1–9 and 35:4–29 list seven kinds of substances — metals, yarn, skins, wood, oil, spices, and gemstones — signifying the totality of supplies.[88]

Exodus chapter 31

2 Chronicles 1:5–6 reports that the bronze altar, which Exodus 38:1–2 reports Bezalel made, still stood before the Tabernacle in Solomon's time, and Solomon sacrificed a thousand burnt offerings on it.

Exodus chapter 32

The report of Exodus 32:1 that "the people assembled" (Template:Hebrew, vayikahel ha'am) is echoed in Exodus 35:1, which opens, "And Moses assembled" (Template:Hebrew, vayakhel Mosheh).

1 Kings 12:25–33 reports a parallel story of golden calves. King Jeroboam of the northern Kingdom of Israel made two calves of gold out of a desire to prevent the kingdom from returning to allegiance to the house of David and the southern Kingdom of Judah.[89] In Exodus 32:4, the people said of the Golden Calf, "This is your god, O Israel, that brought you up out of the land of Egypt." Similalrly, in 1 Kings 12:28, Jeroboam told the people of his golden calves, "You have gone up long enough to Jerusalem; behold your gods, O Israel, that brought you up out of the land of Egypt." Jeroboam set up one of the calves in Bethel, and the other in Dan, and the people went to worship before the calf in Dan.[90] Jeroboam made houses of high places, and made priests from people who were not Levites.[91] He ordained a feast like Sukkot on the fifteenth day of the eighth month (a month after the real Sukkot), and he went up to the altar at Bethel to sacrifice to the golden calves that he had made, and he installed his priests there.[92]

In Exodus 32:13 and Deuteronomy 9:27, Moses called on God to "remember" God's covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to deliver the Israelites from God's wrath after the incident of the Golden Calf. Similarly, God remembered Noah to deliver him from the flood in Genesis 8:1; God promised to remember God's covenant not to destroy the Earth again by flood in Genesis 9:15–16; God remembered Abraham to deliver Lot from the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah in Genesis 19:29; God remembered Rachel to deliver her from childlessness in Genesis 30:22; God remembered God's covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob to deliver the Israelites from Egyptian bondage in Exodus 2:24 and 6:5–6; God promised to "remember" God's covenant with Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham to deliver the Israelites and the Land of Israel in Leviticus 26:42–45; the Israelites were to blow upon their trumpets to be remembered and delivered from their enemies in Numbers 10:9; Samson called on God to deliver him from the Philistines in Judges 16:28; Hannah prayed for God to remember her and deliver her from childlessness in 1 Samuel 1:11 and God remembered Hannah's prayer to deliver her from childlessness in 1 Samuel 1:19; Hezekiah called on God to remember Hezekiah's faithfulness to deliver him from sickness in 2 Kings 20:3 and Isaiah 38:3; Jeremiah called on God to remember God's covenant with the Israelites to not condemn them in Jeremiah 14:21; Jeremiah called on God to remember him and think of him, and avenge him of his persecutors in Jeremiah 15:15; God promises to remember God's covenant with the Israelites and establish an everlasting covenant in Ezekiel 16:60; God remembers the cry of the humble in Zion to avenge them in Psalm 9:13; David called upon God to remember God's compassion and mercy in Psalm 25:6; Asaph called on God to remember God's congregation to deliver them from their enemies in Psalm 74:2; God remembered that the Israelites were only human in Psalm 78:39; Ethan the Ezrahite called on God to remember how short Ethan's life was in Psalm 89:48; God remembers that humans are but dust in Psalm 103:14; God remembers God's covenant with Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in Psalm 105:8–10; God remembers God's word to Abraham to deliver the Israelites to the Land of Israel in Psalm 105:42–44; the Psalmist calls on God to remember him to favor God's people, to think of him at God's salvation, that he might behold the prosperity of God's people in Psalm 106:4–5; God remembered God's covenant and repented according to God's mercy to deliver the Israelites in the wake of their rebellion and iniquity in Psalm 106:4–5; the Psalmist calls on God to remember God's word to God's servant to give him hope in Psalm 119:49; God remembered us in our low estate to deliver us from our adversaries in Psalm 136:23–24; Job called on God to remember him to deliver him from God's wrath in Job 14:13; Nehemiah prayed to God to remember God's promise to Moses to deliver the Israelites from exile in Nehemiah 1:8; and Nehemiah prayed to God to remember him to deliver him for good in Nehemiah 13:14–31.

Exodus chapter 34

James Limburg, Professor Emeritus at Luther Seminary, asked whether the Book of Jonah might be a Midrash (a homiletical exposition of a Biblical text) on a text like Exodus 34:6 (the Attributes of God).[93]

Professor Benjamin Sommer of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America read Exodus 34:6–7 and Numbers 14:18–20 to teach that God punishes children for their parents’ sins as a sign of mercy to the parents: When sinning parents repent, God defers their punishment to their offspring. Sommer argued that other Biblical writers, engaging in inner-Biblical interpretation, rejected that notion in Deuteronomy 7:9–10, Jonah 4:2, and Psalm 103:8–10. Sommer argued that Psalm 103:8–10, for example, quoted Exodus 34:6–7, which was already an authoritative and holy text, but revised the morally troubling part: Where Exodus 34:7 taught that God punishes sin for generations, Psalm 103:9–10 maintained that God does not contend forever. Sommer argued that Deuteronomy 7:9–10 and Jonah 4:2 similarly quoted Exodus 34:6–7 with revision. Sommer asserted that Deuteronomy 7:9–10, Jonah 4:2, and Psalm 103:8–10 do not try to tell us how to read Exodus 34:6–7; that is, they do not argue that Exodus 34:6–7 somehow means something other than what it seems to say. Rather, they repeat Exodus 34:6–7 while also disagreeing with part of it.[94]

Passover

Exodus 34:18 refers to the Festival of Passover, calling it "the Feast of Unleavened Bread." In the Hebrew Bible, Passover is called:

- "Passover" (Pesach, Template:Hebrew);[95]

- "The Feast of Unleavened Bread" (Chag haMatzot, Template:Hebrew);[96] and

- "A holy convocation" or "a solemn assembly" (mikrah kodesh, Template:Hebrew).[97]

Some explain the double nomenclature of "Passover" and "Feast of Unleavened Bread" as referring to two separate feasts that the Israelites combined sometime between the Exodus and when the Biblical text became settled.[98] Exodus 34:18–20 and Deuteronomy 15:19–16:8 indicate that the dedication of the firstborn also became associated with the festival.

Some believe that the "Feast of Unleavened Bread" was an agricultural festival at which the Israelites celebrated the beginning of the grain harvest. Moses may have had this festival in mind when in Exodus 5:1 and 10:9 he petitioned Pharaoh to let the Israelites go to celebrate a feast in the wilderness.[99]

"Passover," on the other hand, was associated with a thanksgiving sacrifice of a lamb, also called "the Passover," "the Passover lamb," or "the Passover offering."[100]

Exodus 12:5–6, Leviticus 23:5, and Numbers 9:3 and 5, and 28:16 direct "Passover" to take place on the evening of the fourteenth of Aviv (Nisan in the Hebrew calendar after the Babylonian captivity). Joshua 5:10, Ezekiel 45:21, Ezra 6:19, and 2 Chronicles 35:1 confirm that practice. Exodus 12:18–19, 23:15, and 34:18, Leviticus 23:6, and Ezekiel 45:21 direct the "Feast of Unleavened Bread" to take place over seven days and Leviticus 23:6 and Ezekiel 45:21 direct that it begin on the fifteenth of the month. Some believe that the proximity of the dates of the two festivals led to their confusion and merger.[99]

Exodus 12:23 and 27 link the word "Passover" (Pesach, Template:Hebrew) to God's act to "pass over" (pasach, Template:Hebrew) the Israelites' houses in the plague of the firstborn. In the Torah, the consolidated Passover and Feast of Unleavened Bread thus commemorate the Israelites' liberation from Egypt.[101]

The Hebrew Bible frequently notes the Israelites' observance of Passover at turning points in their history. Numbers 9:1–5 reports God's direction to the Israelites to observe Passover in the wilderness of Sinai on the anniversary of their liberation from Egypt. Joshua 5:10–11 reports that upon entering the Promised Land, the Israelites kept the Passover on the plains of Jericho and ate unleavened cakes and parched corn, produce of the land, the next day. 2 Kings 23:21–23 reports that King Josiah commanded the Israelites to keep the Passover in Jerusalem as part of Josiah's reforms, but also notes that the Israelites had not kept such a Passover from the days of the Biblical judges nor in all the days of the kings of Israel or the kings of Judah, calling into question the observance of even Kings David and Solomon. The more reverent 2 Chronicles 8:12–13, however, reports that Solomon offered sacrifices on the festivals, including the Feast of Unleavened Bread. And 2 Chronicles 30:1–27 reports King Hezekiah's observance of a second Passover anew, as sufficient numbers of neither the priests nor the people were prepared to do so before then. And Ezra 6:19–22 reports that the Israelites returned from the Babylonian captivity observed Passover, ate the Passover lamb, and kept the Feast of Unleavened Bread seven days with joy.

Shavuot

Exodus 34:22 refers to the Festival of Shavuot. In the Hebrew Bible, Shavuot is called:

- The Feast of Weeks (Template:Hebrew, Chag Shavuot);[102]

- The Day of the First-fruits (Template:Hebrew, Yom haBikurim);[103]

- The Feast of Harvest (Template:Hebrew, Chag haKatzir);[104] and

- A holy convocation (Template:Hebrew, mikrah kodesh).[105]

Exodus 34:22 associates Shavuot with the first-fruits (Template:Hebrew, bikurei) of the wheat harvest.[106] In turn, Deuteronomy 26:1–11 set out the ceremony for the bringing of the first fruits.

To arrive at the correct date, Leviticus 23:15 instructs counting seven weeks from the day after the day of rest of Passover, the day that they brought the sheaf of barley for waving. Similarly, Deuteronomy 16:9 directs counting seven weeks from when they first put the sickle to the standing barley.

Leviticus 23:16–19 sets out a course of offerings for the fiftieth day, including a meal-offering of two loaves made from fine flour from the first-fruits of the harvest; burnt-offerings of seven lambs, one bullock, and two rams; a sin-offering of a goat; and a peace-offering of two lambs. Similarly, Numbers 28:26–30 sets out a course of offerings including a meal-offering; burnt-offerings of two bullocks, one ram, and seven lambs; and one goat to make atonement. Deuteronomy 16:10 directs a freewill-offering in relation to God's blessing.

Leviticus 23:21 and Numbers 28:26 ordain a holy convocation in which the Israelites were not to work.

2 Chronicles 8:13 reports that Solomon offered burnt-offerings on the Feast of Weeks.

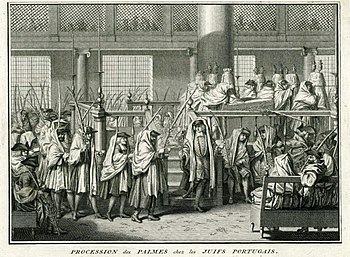

Sukkot

And Exodus 34:22 refers to the Festival of Sukkot, calling it "the Feast of Ingathering." In the Hebrew Bible, Sukkot is called:

- "The Feast of Tabernacles (or Booths)";[107]

- "The Feast of Ingathering";[108]

- "The Feast" or "the festival";[109]

- "The Feast of the Lord";[110]

- "The festival of the seventh month";[111] and

- "A holy convocation" or "a sacred occasion."[112]

Sukkot's agricultural origin is evident from the name "The Feast of Ingathering," from the ceremonies accompanying it, and from the season and occasion of its celebration: "At the end of the year when you gather in your labors out of the field";[104] "after you have gathered in from your threshing-floor and from your winepress."[113] It was a thanksgiving for the fruit harvest.[114] And in what may explain the festival's name, Isaiah reports that grape harvesters kept booths in their vineyards.[115] Coming as it did at the completion of the harvest, Sukkot was regarded as a general thanksgiving for the bounty of nature in the year that had passed.

Sukkot became one of the most important feasts in Judaism, as indicated by its designation as "the Feast of the Lord"[110] or simply "the Feast."[109] Perhaps because of its wide attendance, Sukkot became the appropriate time for important state ceremonies. Moses instructed the children of Israel to gather for a reading of the Law during Sukkot every seventh year.[116] King Solomon dedicated the Temple in Jerusalem on Sukkot.[117] And Sukkot was the first sacred occasion observed after the resumption of sacrifices in Jerusalem after the Babylonian captivity.[118]

In the time of Nehemiah, after the Babylonian captivity, the Israelites celebrated Sukkot by making and dwelling in booths, a practice of which Nehemiah reports: "the Israelites had not done so from the days of Joshua."[119] In a practice related to that of the Four Species, Nehemiah also reports that the Israelites found in the Law the commandment that they "go out to the mountains and bring leafy branches of olive trees, pine trees, myrtles, palms and [other] leafy trees to make booths."[120] In Leviticus 23:40, God told Moses to command the people: "On the first day you shall take the product of hadar trees, branches of palm trees, boughs of leafy trees, and willows of the brook," and "You shall live in booths seven days; all citizens in Israel shall live in booths, in order that future generations may know that I made the Israelite people live in booths when I brought them out of the land of Egypt."[121] The book of Numbers, however, indicates that while in the wilderness, the Israelites dwelt in tents.[122] Some secular scholars consider Leviticus 23:39–43 (the commandments regarding booths and the four species) to be an insertion by a later redactor.[123]

King Jeroboam of the northern Kingdom of Israel, whom 1 Kings 13:33 describes as practicing "his evil way," celebrated a festival on the fifteenth day of the eighth month, one month after Sukkot, "in imitation of the festival in Judah."[124] "While Jeroboam was standing on the altar to present the offering, the man of God, at the command of the Lord, cried out against the altar" in disapproval.[125]

According to the prophet Zechariah, in the messianic era, Sukkot will become a universal festival, and all nations will make pilgrimages annually to Jerusalem to celebrate the feast there.[126]

Milk

In three separate places — Exodus 23:19 and 34:26 and Deuteronomy 14:21 — the Torah prohibits boiling a kid in its mother's milk.

In early nonrabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these early nonrabbinic sources:[127]

Exodus chapter 31

Josephus taught that when the Israelites brought together the materials with great diligence, Moses set architects over the works by the command of God. And these were the very same people that the people themselves would have chosen, had the election been allowed to them: Bezalel, the son of Uri, of the tribe of Judah, the grandson of Miriam, the sister of Moses, and Oholiab, file son of Ahisamach, of the tribe of Dan.[128]

In classical rabbinic interpretation

The parashah is discussed in these rabbinic sources from the era of the Mishnah and the Talmud:[129]

Exodus chapter 30

The Rabbis taught in a Baraita that upon entering a barn to measure the new grain one should recite the blessing, "May it be Your will O Lord, our God, that You may send blessing upon the work of our hands." Once one has begun to measure, one should say, "Blessed be the One who sends blessing into this heap." If, however, one first measured the grain and then recited the blessing, then prayer is in vain, because blessing is not to be found in anything that has been already weighed or measured or numbered, but only in a thing hidden from sight.[130]

Rabbi Abbahu taught that Moses asked God how Israel would be exalted, and God replied in the words of Exodus 30:12 (about collecting the half-shekel tax), "When you raise them up," teaching that collecting contributions from the people elevates them.[131]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that God told David that David called God an inciter, but God would make David stumble over a thing that even school-children knew, namely, that which Exodus 30:12 says, "When you take the sum of the children of Israel according to their number, then shall they give every man a ransom for his soul into the Lord . . . that there be no plague among them." Forthwith, as 1 Chronicles 21:1 reports, "Satan stood up against Israel," and as 2 Samuel 24:1 reports, "He stirred up David against them saying, ‘Go, number Israel.'" And when David did number them, he took no ransom from them, and as 2 Samuel 24:15 reports, "So the Lord sent a pestilence upon Israel from the morning even to the time appointed." The Gemara asked what 2 Samuel 24:15 meant by "the time appointed." Samuel the elder, the son-in-law of Rabbi Hanina, answered in the name of Rabbi Hanina: From the time of slaughtering the continual offering (at dawn) until the time of sprinkling the blood. Rabbi Johanan said it meant at midday. Reading the continuation of 2 Samuel 24:16, "And He said to the Angel that destroyed the people, ‘It is enough (Template:Hebrew, rav),'" Rabbi Eleazar taught that God told the Angel to take a great man (Template:Hebrew, rav) from among them, through whose death many sins could be expiated. So Abishai son of Zeruiah then died, and he was individually equal in worth to the greater part of the Sanhedrin. Reading 1 Chronicles 21:15, "And as he was about to destroy, the Lord beheld, and He repented," the Gemara ask what God beheld. Rav said God beheld Jacob, as Genesis 32:3 reports, "And Jacob said when he beheld them." Samuel said that God beheld the ashes of the ram of Isaac, as Genesis 22:8 says, "God will see for Himself the lamb." Rabbi Isaac Nappaha taught that God saw the atonement money that Exodus 30:16 reports God required Moses to collect. For in Exodus 30:16, God said, "And you shall take the atonement money from the children of Israel, and shalt appoint it for the service of the tent of meeting, that it may be a memorial for the children of Israel before the Lord, to make atonement for your souls.'" (Thus God said that at some future time, the money would provide atonement.) Alternatively, Rabbi Johanan taught that God saw the Temple. For Genesis 22:14 explained the meaning of the name that Abraham gave to the mountain where Abraham nearly sacrificed Isaac to be, "In the mount where the Lord is seen." (Solomon later built the Temple on that mountain, and God saw the merit of the sacrifices there.) Rabbi Jacob bar Iddi and Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani differed on the matter. One said that God saw the atonement money that Exodus 30:16 reports God required Moses to collect from the Israelites, while the other said that God saw the Temple. The Gemara concluded that the more likely view was that God saw the Temple, as Genesis 22:14 can be read to say, "As it will be said on that day, ‘in the mount where the Lord is seen.'"[132]

The first four chapters of Tractate Shekalim in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the law of the half-shekel head tax commanded by Exodus 30:13–16.[133]

Reading Exodus 30:13, "This they shall give . . . half a shekel for an offering to the Lord," to indicate that God pointed with God’s finger, Rabbi Ishmael said that each of the five fingers of God’s right hand appertain to the mystery of Redemption. Rabbi Ishmael said that God showed the little finger of the hand to Noah, pointing out how to make the Ark, as in Genesis 6:15, God says, "And this is how you shall make it." With the second finger, next to the little one, God smote the Egyptians with the ten plagues, as Exodus 8:15 (8:19 in the KJV) says, "The magicians said to Pharaoh, ‘This is the finger of God.’" With the middle finger, God wrote the Tablets of the Law, as Exodus 31:18 says, "And He gave to Moses, when He had made an end of communing with him . . . tables of stone, written with the finger of God." With the index finger, God showed Moses what the children of Israel should give for the redemption of their souls, as Exodus 30:13 says, "This they shall give . . . half a shekel for an offering to the Lord." With the thumb and all the hand, God will in the future smite God’s enemies (who Rabbi Ishmael identified as the children of Esau and Ishmael), as Micah 5:9 says, "Let your hand be lifted up above your adversaries, and let all your enemies be cut off."[134]

The Mishnah taught that any sacrifice performed by a priest who had not washed his hands and feet at the laver as required by Exodus 30:18–21 was invalid.[135]

Rabbi Jose the son of Rabbi Hanina taught that a priest was not permitted to wash in a laver that did not contain enough water to wash four priests, for Exodus 40:31 says, "That Moses and Aaron and his sons might wash their hands and their feet thereat." ("His sons" implies at least two priests, and adding Moses and Aaron makes four.)[136]

The Mishnah reported that the High Priest Ben Katin made 12 spigots for the laver, where there had been two before. Ben Katin also made a machine for the laver, so that its water would not become unfit by remaining overnight.[137]

A Baraita taught that Josiah hid away the anointing oil referred to in Exodus 30:22–33, the Ark referred to in Exodus 37:1–5, the jar of manna referred to in Exodus 16:33, Aaron's rod with its almonds and blossoms referred to in Numbers 17:23, and the coffer that the Philistines sent the Israelites as a gift along with the Ark and concerning which the priests said in 1 Samuel 6:8, “And put the jewels of gold, which you returned Him for a guilt offering, in a coffer by the side thereof [of the Ark]; and send it away that it may go.” Having observed that Deuteronomy 28:36 predicted, “The Lord will bring you and your king . . . to a nation that you have not known,” Josiah ordered the Ark hidden away, as 2 Chronicles 35:3 reports, “And he [Josiah] said to the Levites who taught all Israel, that were holy to the Lord, ‘Put the Holy Ark into the house that Solomon the son of David, King of Israel, built; there shall no more be a burden upon your shoulders; now serve the Lord your God and his people Israel.’” Rabbi Eleazar deduced that Josiah hid the anointing oil and the other objects at the same time as the Ark from the common use of the expressions “there” in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and “there” in Exodus 30:6 with regard to the Ark, “to be kept” in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and “to be kept” in Numbers 17:25 with regard to Aaron’s rod, and “generations” in Exodus 16:33 with regard to the manna and “generations” in Exodus 30:31 with regard to the anointing oil.[138]

The Mishnah counted compounding anointing oil in the formula prescribed in Exodus 30:23–33 and using such sacred anointing oil in a way prohibited by Exodus 30:32 as 2 among 36 transgressions in the Torah punishable with excision (Template:Hebrew, karet). The Mishnah taught that for these transgressions, one was liable to excision if one violated the commandment willfully. If one violated the commandment in error, one was liable to a sin offering. If there was a doubt whether one had violated the commandment, one was liable to a suspensive guilt offering, except, taught Rabbi Meir, in the case of one who defiled the Temple or its consecrated things, in which case one was liable to a sliding-scale sacrifice (according to the means of the transgressor, as provided in Leviticus 5:6–11).[139]

Rabbi Judah taught that many miracles attended the anointing oil that Moses made in the wilderness. There were originally only 12 logs (about a gallon) of the oil. Much of it must have been absorbed in the mixing pot, much must have been absorbed in the roots of the spices used, and much of it must have evaporated during cooking. Yet it was used to anoint the Tabernacle and its vessels, Aaron and his sons throughout the seven days of the consecration, and subsequent High Priests and kings. The Gemara deduced from Exodus 30:31, "This (Template:Hebrew, zeh) shall be a holy anointing oil unto Me throughout your generations," that 12 logs existed. The Gemara calculated the numerical value of the Hebrew letters in the word Template:Hebrew, zeh ("this") to be 12 (employing Gematria, where Template:Hebrew equals 7 and Template:Hebrew equals 5), indicating that 12 logs of the oil were preserved throughout time.[140]

Exodus chapter 31

Rabbi Johanan taught that God proclaims three things for God's Self: famine, plenty, and a good leader. 2 Kings 8:1 shows that God proclaims famine, when it says: "The Lord has called for a famine." Ezekiel 36:29 shows that God proclaims plenty, when it says: "I will call for the corn and will increase it." And Exodus 31:1–2 shows that God proclaims a good leader, when it says: "And the Lord spoke to Moses, saying, ‘See I have called by name Bezalel, the son of Uri.'" Rabbi Isaac taught that we cannot appoint a leader over a community without first consulting the people, as Exodus 35:30 says: "And Moses said to the children of Israel: ‘See, the Lord has called by name Bezalel, the son of Uri.'" Rabbi Isaac taught that God asked Moses whether Moses considered Bezalel suitable. Moses replied that if God thought Bezalel suitable, surely Moses must also. God told Moses that, all the same, Moses should go and consult the people. Moses then asked the Israelites whether they considered Bezalel suitable. They replied that if God and Moses considered Bezalel suitable, then surely they had to, as well. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that Bezalel (Template:Hebrew, whose name can be read Template:Hebrew, betzel El, "in the shadow of God") was so called because of his wisdom. When God told Moses (in Exodus 31:7) to tell Bezalel to make a tabernacle, an ark, and vessels, Moses reversed the order and told Bezalel to make an ark, vessels, and a tabernacle. Bezalel replied to Moses that as a rule, one first builds a house and then brings vessels into it, but Moses directed to make an ark, vessels, and a tabernacle. Bezalel asked where he would put the vessels. And Bezalel asked whether God had told Moses to make a tabernacle, an ark, and vessels. Moses replied that perhaps Bezalel had been in the shadow of God (Template:Hebrew, betzel El) and had thus come to know this. Rav Judah taught in the name of Rav that Exodus 35:31 indicated that God endowed Bezalel with the same attribute that God used in creating the universe. Rav Judah said in the name of Rav that Bezalel knew how to combine the letters by which God created the heavens and earth. For Exodus 35:31 says (about Bezalel), "And He has filled him with the spirit of God, in wisdom and in understanding, and in knowledge," and Proverbs 3:19 says (about creation), "The Lord by wisdom founded the earth; by understanding He established the heavens," and Proverbs 3:20 says, "By His knowledge the depths were broken up."[141]

Rabbi Tanhuma taught in the name of Rav Huna that even the things that Bezalel did not hear from Moses he conceived of on his own exactly as they were told to Moses from Sinai. Rabbi Tanhuma said in the name of Rav Huna that one can deduce this from the words of Exodus 38:22, "And Bezalel the son of Uri, the son of Hur, of the tribe of Judah, made all that the Lord commanded Moses." For Exodus 38:22 does not say, "that Moses commanded him," but, "that the Lord commanded Moses."[142]

And the Agadat Shir ha-Shirim taught that Bezalel and Oholiab went up Mount Sinai, where the heavenly Sanctuary was shown to them.[143]

Tractate Shabbat in the Mishnah, Tosefta, Jerusalem Talmud, and Babylonian Talmud interpreted the laws of the Sabbath in Exodus 16:23 and 29; 20:7–10 (20:8–11 in the NJPS); 23:12; 31:13–17; 35:2–3; Leviticus 19:3; 23:3; Numbers 15:32–36; and Deuteronomy 5:11 (5:12 in the NJPS).[144]

Reading the words "everyone who profanes [the Sabbath] shall surely be put to death" in Exodus 31:14 (in which the verb for death is doubled), Samuel deduced that the Torah decreed many deaths for desecrating the Sabbath. The Gemara posited that perhaps Exodus 31:14 refers to willful desecration. The Gemara answered that Exodus 31:14 is not needed to teach that willful transgression of the Sabbath is a capital crime, for Exodus 35:2 says, "Whoever does any work therein shall be put to death." The Gemara concluded that Exodus 31:14 thus must apply to an unwitting offender, and in that context, the words "shall surely be put to death" mean that the inadvertent Sabbath violator will "die" monetarily because of the violator's need to bring costly sacrifices.[145]

The Sifra taught that the incidents of the blasphemer in Leviticus 24:11–16 and the wood gatherer in Numbers 15:32–36 happened at the same time, but the Israelites did not leave the blasphemer with the wood gatherer, for they knew that the wood gatherer was going to be executed, as Exodus 31:14 directed, "those who profane it [the Sabbath] shall be put to death." But they did not know the correct form of death penalty for him, for God had not yet been specified what to do to him, as Numbers 15:34 says, "for it had not [yet] been specified what should be done to him." With regard to the blasphemer, the Sifra read Leviticus 24:12, "until the decision of the Lord should be made clear to them," to indicate that they did not know whether or not the blasphemer was to be executed. (And if they placed the blasphemer together with the wood gatherer, it might have caused the blasphemer unnecessary fear, as he might have concluded that he was on death row. Therefore, they held the two separately.)[146]

A Midrash asked to which commandment Deuteronomy 11:22 refers when it says, "For if you shall diligently keep all this commandment that I command you, to do it, to love the Lord your God, to walk in all His ways, and to cleave to Him, then will the Lord drive out all these nations from before you, and you shall dispossess nations greater and mightier than yourselves." Rabbi Levi said that "this commandment" refers to the recitation of the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4–9), but the Rabbis said that it refers to the Sabbath, which is equal to all the precepts of the Torah.[147]

The Alphabet of Rabbi Akiva taught that when God was giving Israel the Torah, God told them that if they accepted the Torah and observed God’s commandments, then God would give them for eternity a most precious thing that God possessed — the World To Come. When Israel asked to see in this world an example of the World To Come, God replied that the Sabbath is an example of the World To Come.[148]

The Mishnah taught that the two Tablets of the Ten Commandments that God gave Moses in Exodus 31:18 were among ten things that God created on the eve of the first Sabbath at twilight.[149]

Rabbi Meir taught that the stone Tablets that God gave Moses in Exodus 31:18 were each 6 handbreadths long, 6 handbreadths wide, and 3 handbreadths thick.[150]

Rabbi Simeon ben Lakish (Resh Lakish) taught that the Torah that God gave Moses was of white fire and its writing of black fire. It was itself fire and it was hewn out of fire and completely formed of fire and given in fire, as Deuteronomy 33:2 says, "At His right hand was a fiery law to them."[151]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman taught that when God passed the two Tablets to Moses (as reported in Exodus 31:18), the Tablets conveyed to Moses a lustrous appearance (as reported in Exodus 34:30).[152]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that from the words of Exodus 31:18, "tablets (Template:Hebrew, luchot) of stone," one may learn that if one regards one's cheeks (Template:Hebrew, lechayav) as stone that is not easily worn away (constantly speaking words of Torah, regardless of the strain on one's facial muscles), one's learning will be preserved, but otherwise it will not.[153]

Reading "the finger of God" in Exodus 31:18, Rabbi Ishmael said that each of the five fingers of God’s right hand appertain to the mystery of Redemption. Rabbi Ishmael said that God wrote the Tablets of the Law with the middle finger, as Exodus 31:18 says, "And He gave to Moses, when He had made an end of communing with him . . . tables of stone, written with the finger of God."[154]

Exodus chapter 32

A Baraita taught that because of God's displeasure with the Israelites, the north wind did not blow on them in any of the 40 years during which they wandered in the wilderness. Rashi attributed God's displeasure to the Golden Calf, although the Tosafot attributed it to the incident of the spies in Numbers 13.[155]

Rabbi Tanhum bar Hanilai taught that Aaron made the Golden Calf in Exodus 32:4 as a compromise with the people's demand in Exodus 32:1 to "make us a god who shall go before us." Rabbi Benjamin bar Japhet, reporting Rabbi Eleazar, interpreted the words of Exodus 32:5, "And when Aaron saw it, he built an altar before it," to mean that Aaron saw (his nephew) Hur lying slain before him and thought that if he did not obey the people, they would kill him as well. (Exodus 24:14 mentions that Moses appointed Hur to share the leadership of the people with Aaron, but after Moses descended from Mount Sinai, Hur's name does not appear again.) Aaron thought that the people would then fulfill the words of Lamentations 2:20, "Shall the Priest and the Prophet be slain in the Sanctuary of God?" and the people would then never find forgiveness. Aaron though it better to let the people worship the Golden Calf, for which they might yet find forgiveness through repentance. And thus Rabbi Tanhum bar Hanilai concluded that it was in reference to Aaron's decision-making in this incident that Psalm 10:3 can be read to mean, "He who praises one who makes a compromise blasphemes God."[156]

The Sages told that Aaron really intended to delay the people until Moses came down, but when Moses saw Aaron beating the Golden Calf into shape with a hammer, Moses thought that Aaron was participating in the sin and was incensed with him. So God told Moses that God knew that Aaron's intentions were good. The Midrash compared it to a prince who became mentally unstable and started digging to undermine his father's house. His tutor told him not to weary himself but to let him dig. When the king saw it, he said that he knew the tutor’s intentions were good, and declared that the tutor would rule over the palace. Similarly, when the Israelites told Aaron in Exodus 32:1, "Make us a god," Aaron replied in Exodus 32:1, "Break off the golden rings that are in the ears of your wives, of your sons, and of your daughters, and bring them to me." And Aaron told them that since he was a priest, they should let him make it and sacrifice to it, all with the intention of delaying them until Moses could come down. So God told Aaron that God knew Aaron’s intention, and that only Aaron would have sovereignty over the sacrifices that the Israelites would bring. Hence in Exodus 28:1, God told Moses, "And bring near Aaron your brother, and his sons with him, from among the children of Israel, that they may minister to Me in the priest's office." The Midrash told that God told this to Moses several months later in the Tabernacle itself when Moses was about to consecrate Aaron to his office. Rabbi Levi compared it to the friend of a king who was a member of the imperial cabinet and a judge. When the king was about to appoint a palace governor, he told his friend that he intended to appoint the friend’s brother. So God made Moses superintendent of the palace, as Numbers 7:7 reports, "My servant Moses is . . . is trusted in all My house," and God made Moses a judge, as Exodus 18:13 reports, "Moses sat to judge the people." And when God was about to appoint a High Priest, God notified Moses that it would be his brother Aaron.[157]

A Midrash noted that in the incident of the Golden Calf, in Exodus 32:2, Aaron told them, "Break off the golden rings that are in the ears of your wives," but the women refused to participate, as Exodus 32:3 indicates when it says, "And all the people broke off the golden rings that were in their ears." Similarly, the Midrash noted that Numbers 14:36 says that in the incident of the spies, "the men . . . when they returned, made all the congregation to murmur against him." The Midrash explained that that is why the report of Numbers 27:1–11 about the daughters of Zelophehad follows immediately after the report of Numbers 26:65 about the death of the wilderness generation. The Midrash noted that Numbers 26:65 says, "there was not left a man of them, save Caleb the son of Jephunneh," because the men had been unwilling to enter the Land. But the Midrash taught that Numbers 27:1 says, "then drew near the daughters of Zelophehad," to show that the women still sought an inheritance in the Land. The Midrash taught that in that generation, the women built up fences that the men broke down.[158]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer expounded on the exchange between God and Moses in Exodus 32:7–14 after the sin of the Golden Calf. The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told that after the incident of the Golden Calf, God told Moses that the Israelites had forgotten God's might and had made an idol. Moses replied to God that while the Israelites had not yet sinned, God had called them "My people," as in Exodus 7:4, God had said, "And I will bring forth My hosts, My people." But Moses noted that once the Israelites had sinned, God told Moses (in Exodus 32:7), "Go, get down, for your people have corrupted themselves." Moses told God that the Israelites were indeed God's people, and God's inheritance, as Deuteronomy 9:29 reports Moses saying, "Yet they are Your people and Your inheritance."[159]

Did the prayer of Moses in Exodus 32:11–14 change God's harsh decree? On this subject, Rabbi Abbahu interpreted David's last words, as reported in 2 Samuel 23:2–3, where David reported that God told him, "Ruler over man shall be the righteous, even he that rules through the fear of God." Rabbi Abbahu read 2 Samuel 23:2–3 to teach that God rules humankind, but the righteous rule God, for God makes a decree, and the righteous may through their prayer annul it.[160]

Rava employed Numbers 30:3 to interpret Exodus 32:11, which says: "And Moses besought (va-yechal) the Lord his God" in connection with the incident of the Golden Calf. Rava noted that Exodus 32:11 uses the term "besought" (va-yechal), while Numbers 30:3 uses the similar term "break" (yachel) in connection with vows. Transferring the use of Numbers 30:3 to Exodus 32:11, Rava reasoned that Exodus 32:11 meant that Moses stood in prayer before God until Moses annulled for God God's vow to destroy Israel, for a master had taught that while people cannot break their vows, others may annul their vows for them.[161] Similarly, Rabbi Berekiah taught in the name of Rabbi Helbo in the name of Rabbi Isaac that Moses absolved God of God's vow. When the Israelites made the Golden Calf, Moses began to persuade God to forgive them, but God explained to Moses that God had already taken an oath in Exodus 22:19 that "he who sacrifices to the gods . . . shall be utterly destroyed," and God could not retract an oath. Moses responded by asking whether God had not granted Moses the power to annul oaths in Numbers 30:3 by saying, "When a man vows a vow to the Lord, or swears an oath to bind his soul with a bond, he shall not break his word," implying that while he himself could not break his word, a scholar could absolve his vow. So Moses wrapped himself in his cloak and adopted the posture of a sage, and God stood before Moses as one asking for the annulment of a vow.[162]

The Gemara deduced from the example of Moses in Exodus 32:11. that one should seek an interceding frame of mind before praying. Rav Huna and Rav Hisda were discussing how long to wait between recitations of the Amidah prayer if one erred in the first reciting and needed to repeat the prayer. One said: long enough for the person praying to fall into a suppliant frame of mind, citing the words "And I supplicated the Lord" in Deuteronomy 3:23. The other said: long enough to fall into an interceding frame of mind, citing the words "And Moses interceded" in Exodus 32:11.[163]

A Midrash compared Noah to Moses and found Moses superior. While Noah was worthy to be delivered from the generation of the Flood, he saved only himself and his family, and had insufficient strength to deliver his generation. Moses, however, saved both himself and his generation when they were condemned to destruction after the sin of the Golden Calf, as Exodus 32:14 reports, “And the Lord repented of the evil that He said He would do to His people.” The Midrash compared the cases to two ships in danger on the high seas, on board of which were two pilots. One saved himself but not his ship, and the other saved both himself and his ship.[164]

Interpreting Exodus 32:15 on the "tablets that were written on both their sides," Rav Chisda said that the writing of the Tablets was cut completely through the Tablets, so that it could be read from either side. Thus the letters mem and samekh, which each form a complete polygon, left some of the stone Tablets in the middle of those letters standing in the air where they were held stable only by a miracle.[165]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman told that when the Israelites exclaimed, "This is your God, O Israel" in Exodus 32:4, Moses was just then descending from Mount Sinai. Joshua told Moses (in Exodus 32:17), "There is a noise of war in the camp." But Moses retorted (in Exodus 32:18), "It is not the voice of them that shout for mastery; neither is it the voice of them that cry for being overcome, but the noise of them that sing do I hear." Rabbi Samuel bar Nahman interpreted the words, "but the noise of them that sing do I hear," to mean that Moses heard the noise of reproach and blasphemy. The men of the Great Assembly noted that Nehemiah 9:18 reports, "They had made a molten calf, and said: ‘This is your God that brought you up out of Egypt.'" That would be sufficient provocation, but Nehemiah 9:18 continues, "And wrought great provocations." The men of the Great Assembly thus concluded that Nehemiah 9:18 demonstrates that in addition to making the Golden Calf, on that occasion the Israelites also uttered reproaches and blasphemy.[166]

A Midrash explained why Moses broke the stone Tablets. When the Israelites committed the sin of the Golden Calf, God sat in judgment to condemn them, as Deuteronomy 9:14 says, "Let Me alone, that I may destroy them," but God had not yet condemned them. So Moses took the Tablets from God to appease God's wrath. The Midrash compared the act of Moses to that of a king's marriage-broker. The king sent the broker to secure a wife for the king, but while the broker was on the road, the woman corrupted herself with another man. The broker (who was entirely innocent) took the marriage document that the king had given the broker to seal the marriage and tore it, reasoning that it would be better for the woman to be judged as an unmarried woman than as a wife.[167]

Rabbi Eleazar taught that one could learn from the words of Exodus 32:16, "carved on the tablets," that if the first two Tablets had not been broken, the Torah would have remained carved forever, and the Torah would never have been forgotten in Israel. Rav Aha bar Jacob said that no nation or tongue would have had any power over Israel, as one can read the word "carved" (Template:Hebrew, charut) in Exodus 32:16 as "freedom" (Template:Hebrew, cheirut). (Thus, for the sake of the original two Tablets, Israel would have remained forever free.)[153]

A Baraita taught that when Moses broke the Tablets in Exodus 32:19, it was one of three actions that Moses took based on his own understanding with which God then agreed. The Gemara explained that Moses reasoned that if the Passover lamb, which was just one of the 613 commandments, was prohibited by Exodus 12:43 to aliens, then certainly the whole Torah should be prohibited to the Israelites, who had acted as apostates with the Golden Calf. The Gemara deduced God's approval from God's mention of Moses' breaking the Tablets in Exodus 34:1. Resh Lakish interpreted this to mean that God gave Moses strength because he broke the Tablets.[168]

A Midrash taught that in recompense for Moses having grown angry and breaking the first set of Tablets in Exodus 32:19, God imposed on Moses the job of carving the second set of two Tablets in Deuteronomy 10:1.[169]

The Rabbis taught that Exodus 32:19 and Deuteronomy 10:1 bear out Ecclesiastes 3:5, "A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together." The Rabbis taught that Ecclesiastes 3:5 refers to Moses. For there was a time for Moses to cast away the Tablets in Exodus 32:19, and a time for him to restore them to Israel in Deuteronomy 10:1.[170]

Reading the report of Exodus 32:20 that Moses "took the calf . . . ground it to powder, and sprinkled it on the water, and made the children of Israel drink it," the Sages interpreted that Moses meant to test the Israelites much as the procedure of Numbers 5:11–31 tested a wife accused of adultery (sotah).[171]

The Rabbis taught that through the word "this," Aaron became degraded, as it is said in Exodus 32:22–24, "And Aaron said: ‘. . . I cast it into the fire, and there came out this calf,'" and through the word "this," Aaron was also elevated, as it is said in Leviticus 6:13, "This is the offering of Aaron and of his sons, which they shall offer to the Lord on the day when he is anointed" to become High Priest.[172]

A Midrash noted that Israel sinned with fire in making the Golden Calf, as Exodus 32:24 says, "And I cast it into the fire, and there came out this calf." And then Bezalel came and healed the wound (and the construction of the Tabernacle made atonement for the sins of the people in making the Golden Calf). The Midrash likened it to the words of Isaiah 54:16, "Behold, I have created the smith who blows the fire of coals." The Midrash taught that Bezalel was the smith whom God had created to address the fire. And the Midrash likened it to the case of a doctor's disciple who applied a plaster to a wound and healed it. When people began to praise him, his teacher, the doctor, said that they should praise the doctor, for he taught the disciple. Similarly, when everybody said that Bezalel had constructed the Tabernacle through his knowledge and understanding, God said that it was God who created him and taught him, as Isaiah 54:16 says, "Behold, I have created the smith." Thus Moses said in Exodus 35:30, "see, the Lord has called by name Bezalel."[173]

Rav Nahman bar Isaac derived from the words "if not, blot me, I pray, out of Your book that You have written" in Exodus 32:32 that three books are opened in heaven on Rosh Hashanah. Rav Kruspedai said in the name of Rabbi Johanan that on Rosh Hashanah, three books are opened in Heaven — one for the thoroughly wicked, one for the thoroughly righteous, and one for those in between. The thoroughly righteous are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of life. The thoroughly wicked are immediately inscribed definitively in the book of death. And the fate of those in between is suspended from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur. If they deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of life; if they do not deserve well, then they are inscribed in the book of death. Rabbi Abin said that Psalm 69:29 tells us this when it says, "Let them be blotted out of the book of the living, and not be written with the righteous." "Let them be blotted out from the book" refers to the book of the wicked. "Of the living" refers to the book of the righteous. "And not be written with the righteous" refers to the book of those in between. Rav Nahman bar Isaac derived this from Exodus 32:32, where Moses told God, "if not, blot me, I pray, out of Your book that You have written." "Blot me, I pray" refers to the book of the wicked. "Out of Your book" refers to the book of the righteous. "That you have written" refers to the book of those in between. It was taught in a Baraita that the House of Shammai said that there will be three groups at the Day of Judgment — one of thoroughly righteous, one of thoroughly wicked, and one of those in between. The thoroughly righteous will immediately be inscribed definitively as entitled to everlasting life; the thoroughly wicked will immediately be inscribed definitively as doomed to Gehinnom, as Daniel 12:2 says, "And many of them who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life and some to reproaches and everlasting abhorrence." Those in between will go down to Gehinnom and scream and rise again, as Zechariah 13:9 says, "And I will bring the third part through the fire, and will refine them as silver is refined, and will try them as gold is tried. They shall call on My name and I will answer them." Of them, Hannah said in 1 Samuel 2:6, "The Lord kills and makes alive, He brings down to the grave and brings up." The House of Hillel, however, taught that God inclines the scales towards grace (so that those in between do not have to descend to Gehinnom), and of them David said in Psalm 116:1–3, "I love that the Lord should hear my voice and my supplication . . . The cords of death compassed me, and the straits of the netherworld got hold upon me," and on their behalf David composed the conclusion of Psalm 116:6, "I was brought low and He saved me."[174]

Exodus chapter 33

Reading Exodus 24:3, Rabbi Simlai taught that when the Israelites gave precedence to "we will do" over "we will hear," 600,000 ministering angels came and set two crowns on each Israelite man, one as a reward for "we will do" and the other as a reward for "we will hearken." But as soon as the Israelites committed the sin of the Golden Calf, 1.2 million destroying angels descended and removed the crowns, as it is said in Exodus 33:6, "And the children of Israel stripped themselves of their ornaments from mount Horeb."[175]

The Gemara reported a number of Rabbis' reports of how the Land of Israel did indeed flow with "milk and honey," as described in Exodus 3:8 and 17, 13:5, and 33:3, Leviticus 20:24, Numbers 13:27 and 14:8, and Deuteronomy 6:3, 11:9, 26:9 and 15, 27:3, and 31:20. Once when Rami bar Ezekiel visited Bnei Brak, he saw goats grazing under fig trees while honey was flowing from the figs, and milk dripped from the goats mingling with the fig honey, causing him to remark that it was indeed a land flowing with milk and honey. Rabbi Jacob ben Dostai said that it is about three miles from Lod to Ono, and once he rose up early in the morning and waded all that way up to his ankles in fig honey. Resh Lakish said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey of Sepphoris extend over an area of sixteen miles by sixteen miles. Rabbah bar Bar Hana said that he saw the flow of the milk and honey in all the Land of Israel and the total area was equal to an area of twenty-two parasangs by six parasangs.[176]

Rav Judah taught in the name of Rav that as Moses was dying, Joshua quoted back to Moses the report of Exodus 33:11 about how Joshua stood by the side of Moses all the time. Rav Judah reported in the name of Rav that when Moses was dying, he invited Joshua to ask him about any doubts that Joshua might have. Joshua replied by asking Moses whether Joshua had ever left Moses for an hour and gone elsewhere. Joshua asked Moses whether Moses had not written in Exodus 33:11, "The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as one man speaks to another. . . . But his servant Joshua the son of Nun departed not out of the Tabernacle." Joshua's words wounded Moses, and immediately the strength of Moses waned, and Joshua forgot 300 laws, and 700 doubts concerning laws arose in Joshua's mind. The Israelites then arose to kill Joshua (unless he could resolve these doubts). God then told Joshua that it was not possible to tell him the answers (for, as Deuteronomy 30:11–12 tells, the Torah is not in Heaven). Instead, God then directed Joshua to occupy the Israelites' attention in war, as Joshua 1:1–2 reports.[177]

Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani taught in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that the report of Exodus 33:11 helped to illuminate the words of Joshua 1:8 as a blessing. Ben Damah the son of Rabbi Ishmael's sister once asked Rabbi Ishmael whether one who had studied the whole Torah might learn Greek wisdom. Rabbi Ishmael replied by reading to Ben Damah Joshua 1:8, "This book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth, but you shall meditate therein day and night." And then Rabbi Ishmael told Ben Damah to go find a time that is neither day nor night and learn Greek wisdom then. Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani, however, taught in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that Joshua 1:8 is neither duty nor command, but a blessing. For God saw that the words of the Torah were most precious to Joshua, as Exodus 33:11 says, "The Lord would speak to Moses face to face, as one man speaks to another. And he would then return to the camp. His minister Joshua, the son of Nun, a young man, departed not out of the tent." So God told Joshua that since the words of the Torah were so precious to him, God assured Joshua (in the words of Joshua 1:8) that "this book of the law shall not depart out of your mouth." A Baraita was taught in the School of Rabbi Ishmael, however, that one should not consider the words of the Torah as a debt that one should desire to discharge, for one is not at liberty to desist from them.[178]

A Midrash taught that Proverbs 27:18, "And he who waits on his master shall be honored," alludes to Joshua, for Joshua ministered to Moses day and night, as reported by Exodus 33:11, which says, "Joshua departed not out of the Tent," and Numbers 11:28, which says, "Joshua . . . said: ‘My lord Moses, shut them in.'" Consequently, God honored Joshua by saying of Joshua in Numbers 27:21: "He shall stand before Eleazar the priest, who shall inquire for him by the judgment of the Urim." And because Joshua served his master Moses, Joshua attained the privilege of receiving the Holy Spirit, as Joshua 1:1 reports, "Now it came to pass after the death of Moses . . . that the Lord spoke to Joshua, the minister of Moses." The Midrash taught that there was no need for Joshua 1:1 to state, "the minister of Moses," so the purpose of the statement "the minister of Moses" was to explain that Joshua was awarded the privilege of prophecy because he was the minister of Moses.[179]

Rav Nachman taught that the angel of whom God spoke in Exodus 23:20 was Metatron (Template:Hebrew). Rav Nahman warned that one who is as skilled in refuting heretics as Rav Idit should do so, but others should not. Once a heretic asked Rav Idit why Exodus 24:1 says, "And to Moses He said, ‘Come up to the Lord,'" when surely God should have said, "Come up to Me." Rav Idit replied that it was the angel Metatron who said that, and that Metatron's name is similar to that of his Master (and indeed the gematria (numerical value of the Hebrew letters) of Metatron (Template:Hebrew) equals that of Shadai (Template:Hebrew), God's name in Genesis 17:1 and elsewhere) for Exodus 23:21 says, "for my name is in him." But if so, the heretic retorted, we should worship Metatron. Rav Idit replied that Exodus 23:21 also says, "Be not rebellious against him," by which God meant, "Do not exchange Me for him" (as the word for "rebel," (tamer, Template:Hebrew) derives from the same root as the word "exchange"). The heretic then asked why then Exodus 23:21 says, "he will not pardon your transgression." Rav Idit answered that indeed Metatron has no authority to forgive sins, and the Israelites would not accept him even as a messenger, for Exodus 33:15 reports that Moses told God, "If Your Presence does not go with me, do not carry us up from here."[180]

A Baraita taught in the name of Rabbi Joshua ben Korhah that God told Moses that when God wanted to be seen at the burning bush, Moses did not want to see God's face; Moses hid his face in Exodus 3:6, for he was afraid to look upon God. And then in Exodus 33:18, when Moses wanted to see God, God did not want to be seen; in Exodus 33:20, God said, "You cannot see My face." But Rabbi Samuel bar Nahmani said in the name of Rabbi Jonathan that in compensation for three pious acts that Moses did at the burning bush, he was privileged to obtain three rewards. In reward for hiding his face in Exodus 3:6, his face shone in Exodus 34:29. In reward his fear of God in Exodus 3:6, the Israelites were afraid to come near him in Exodus 34:30. In reward for his reticence "to look upon God," he beheld the similitude of God in Numbers 12:8.[181]

The Pirke De-Rabbi Eliezer told what happened in Exodus 33:18–34:6 after Moses asked to behold God's Presence in Exodus 33:18. Moses foretold that he would behold God's Glory and make atonement for the Israelites' iniquities on Yom Kippur. On that day, Moses asked God (in the words of Exodus 33:18) "Show me, I pray, Your Glory." God told Moses that Moses was not able to see God's Glory lest he die, as Exodus 33:20 reports God said, "men shall not see Me and live," but for the sake of God's oath to Moses, God agreed to do as Moses asked. God instructed Moses to stand at the entrance of a cave, and God would cause all God's angels to pass before Moses. God told Moses to stand his ground, and not to fear, as Exodus 33:19 reports, "And He said, I will make all My Goodness pass before you." God told Moses that when he heard the Name that God had spoken to him, then Moses would know that God was before him, as Exodus 33:19 reports. The ministering angels complained that they served before God day and night, and they were unable to see God's Glory, but this man Moses born of woman desired to see God's Glory. The angels arose in wrath and excitement to kill Moses, and he came near to death. God intervened in a cloud to protect Moses, as Exodus 34:5 reports, "And the Lord descended in the cloud." God protected Moses with the hollow of God's hand so that he would not die, as Exodus 33:22 reports, "And it shall come to pass, while My Glory passes by, that I will put you in a cleft of the rock, and I will cover you with My hand." When God had passed by, God removed the hollow of God's hand from Moses, and he saw traces of the Shechinah, as Exodus 33:23 says, "And I will take away My hand, and you shall see my back." Moses began to cry with a loud voice, and Moses said the words of Exodus 34:6–7: "O Lord, O Lord, a God full of compassion and gracious . . . ." Moses asked God to pardon the iniquities of the people in connection with the Golden Calf. God told Moses that if he had asked God then to pardon the iniquities of all Israel, even to the end of all generations, God would have done so, as it was the appropriate time. But Moses had asked for pardon with reference to the Golden Calf, so God told Moses that it would be according to his words, as Numbers 14:20 says, "And the Lord said, ‘I have pardoned according to your word.'"[182]

Rabbi Jose ben Halafta employed Exodus 33:21 to help explain how God can be called "the Place." Reading the words, "And he lighted upon the place," in Genesis 28:11 to mean, "And he met the Divine Presence (Shechinah)," Rav Huna asked in Rabbi Ammi's name why Genesis 28:11 assigns to God the name "the Place." Rav Huna explained that it is because God is the Place of the world (the world is contained in God, and not God in the world). Rabbi Jose ben Halafta taught that we do not know whether God is the place of God's world or whether God's world is God's place, but from Exodus 33:21, which says, "Behold, there is a place with Me," it follows that God is the place of God's world, but God's world is not God's place. Rabbi Isaac taught that reading Deuteronomy 33:27, "The eternal God is a dwelling place," one cannot know whether God is the dwelling-place of God's world or whether God's world is God's dwelling-place. But reading Psalm 90:1, "Lord, You have been our dwelling-place," it follows that God is the dwelling-place of God's world, but God's world is not God's dwelling-place. And Rabbi Abba ben Judan taught that God is like a warrior riding a horse with the warrior's robes flowing over on both sides of the horse. The horse is subsidiary to the rider, but the rider is not subsidiary to the horse. Thus Habakkuk 3:8 says, "You ride upon Your horses, upon Your chariots of victory."[183]

Exodus chapter 34

Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai explained why God carved the first two Tablets but Moses carved the second two, as God instructed in Exodus 34:1. Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai compared it to the case of a king who took a wife and paid for the paper for the marriage contract, the scribe, and the wedding dress. But when he saw her cavorting with one of his servants, he became angry with her and sent her away. Her agent came to the king and argued that she had been raised among servants and was thus familiar with them. The king told the agent that if he wished that the king should become reconciled with her, the agent should pay for the paper and the scribe for a new wedding contract and the king would sign it. Similarly, Moses spoke to God after the Israelites had committed the sin of the Golden Calf. Moses argued that God knew that God had brought the Israelites out of Egypt, a house of idolatry. Then God answered that if Moses desired that God should become reconciled with the Israelites, then Moses would have to bring the Tablets at his own expense and God would append God's signature, as God says in Exodus 34:1: "And I will write upon the tablets."[184]