Metcalfe House

| Metcalfe House | |

|---|---|

Dilkhusha | |

Dilkhusha or Metcalfe House in Qutb Archaeological Village, in ruins as on date | |

| Former names | Quli Khan Tomb |

| General information | |

| Type | Mansions |

| Architectural style | Mughul and European |

| Location | Qutb Complex (Archaeological Village) |

| Coordinates | 28°31′21″N 77°11′13″E / 28.52244°N 77.18695°E |

| Current tenants | Archaeological Survey of India |

| Destroyed | 1857 |

| Client | Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, 4th Baronet |

| Landlord | Government of India |

| Technical details | |

| Structural system | Stones and Brick |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, 4th Baronet |

Metcalfe House is the name given to two residential houses built in the 19th century in Delhi; one is near Old Delhi Civil Lines and the other is in Mehrauli, South Delhi. These were built by Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, 4th Baronet (1795–1853), the refined Civil Servant, when he was the Governor General’s last British Resident (Agent) at the Mughal Court of Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar II.[1][2][3]

The first house near the Civil Lines, called the ‘town house’, was built in 1835 in colonial style, near the present day Inter State Bus Terminal (ISBT). He resided there till his death in 1853. It was badly damaged during the 1857 Indian War of Independence (well known as the Uprising). It was repaired subsequently. His son Sir Theophilus Metcalfe (who was deeply involved during British counter offensive to the Uprising) inherited it. The house exchanged hands several times before it finally came under the possession of the Government of India. Between 1920 and 1926, it also remained the seat of the Council of State of the Central Legislative Assembly, which eventually paved way for the present Rajya Sabha, till the inauguration of the Parliament House in New Delhi.[4] It now houses the highly secured offices and residences of the Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre (DESIDOC) and Defence Terrain Research Laboratory (DTRL), and many other divisions of the Defence Research & Development Organisation (DRDO). It is out of limits for visitors and photography.[2][3][5]

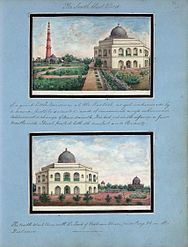

The second Metcalfe House, known as ‘the retreat’ or ‘Dilkhusha’, was also built by Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe as a country house in Mehrauli in South Delhi in Qutb Complex. 'Dilkhusha' in Urdu language means "Delight of the Heart". He refurbished the 16th century Mughal tomb of Quli Khan in true English style as a pleasure retreat by surrounding it with many rest houses, follies and gardens. He used to lease out his retreat as a guest house to honeymooning couples, as it provided an idyllic view of the Qutub Minar with its surrounding structures. An inscription at site (photo of plaque in the gallery) testifies that Metcalfe rented out this house to honeymooning couples.[1][3][6][7]

The town house

Metcalfe built his town house, close to the Yamuna River on its right bank, on the old Metcalfe road, now rechristened as Mahatma Gandhi Road, in the heart of the Old Delhi. It was also known as ‘Jahan Numa’ meaning "World Showing". The workers who built this mansion and attendants at Metcalfe's house called it "Matka Kothi", ('Metcalfe' pronounced as "Matka" and ‘Kothi’ means "House" in Hindi language) a corrupted version; for them the name ‘Metcalfe House’ was a tongue twister. Built as a huge palatial house in European style (colonial style), it had Indian adaptations of high ceiling and small windows and doors to suit local climatic conditions. It was built as a counter to the Mughal Emperor’s Red Fort Palace close by. It was built as a double storied mansion with a large but an impressive façade (that is stated to have been substantially changed in 1913). It had creative underground passageways, one of which was used as a billiards room (pictured). The mansion was surrounded by well manicured garden of cypress tree lined pathways, flowerbeds, orange groves, roads and a swimming pool. The doors of the regal building were festooned with mistletoe and holly.[1][6][8][9]

The wide verandah, encircling the main building on all sides, was supported on impressive stone columns. Inventive underground rooms called the tykhanas were used for cool comforts during the summer season and for playing billiards. A library with 25,000 books and a Napoleon gallery with relics of Napoleon were part of the displays in the large building, apart from beautiful oil paintings and rosewood Georgian furniture. However, during the Uprising of 1857, there was extensive damage to the buildings, all the documents and displays. It is said that Metcalfe had bought the land for building his town house from Gujjars and the same Gujjars ransacked and damaged it during the Upraising in 1857. Theophilus Metcalfe, son of Sir Thomas Metcalfe (died 1853), named as the "One-eyed Metcalfe" due to his monocle, was the city magistrate during the Uprising. He was accused of vengeful destruction of the city and reprisals against its residents, particularly Muslims. During the days of its glory, the town house was famous for the high society social gatherings held in its premises. Extravagant Christmas and New Year parties were held here. An album titled 'Reminiscences of Imperial Delhi’, which had 89 folios with about 130 paintings (a few pictured here) of the Mughal and pre-Mughal period monuments, was compiled by Metacalfe with a transcript written by him to his daughter Emily. In this transcript, he piognantly describes the house and the happy incidents that occurred there. It is better quoted in his own words than paraphrased (the photos also show the manuscript).[10]

In this once happy home you all passed your earliest infancy. With exception to Emy and Charley all were born here- and all but Charley have received the initiatory right [sic] of baptism by which Ye were made member of Christ Children of God and inheritors by promise of the Kingdom of Heaven. To your father it has been endeared by many years of more…

An unusual tale recounted is of a lavish Christmas Eve party in 1895 held at this house in which a mysterious Englishman was murdered in the antechamber and simultaneously a fire also broke out that destroyed Metcalfe’s Testimonials. The murder and reasons for the fire are shrouded in mystery. The house was rebuilt in 1913 with Gothic arches but can now be glimpsed from outside only, since it is occupied by the Defense establishment of the DRDO.[9][11]

The Retreat or Dilkhusha

The second house in Mehrauli was initially a tomb of Muhammad Quli Khan, brother of Adham Khan, a general and foster brother of Emperor Akbar. The octagonal Mughal tomb built in the 17th century was bought by Metcalfe and remodeled in the style of European residences with extensive gardens and follies for use as a pleasure resort during the monsoon season. He called it the ‘Dilkhusha’ (also see under External link of the album showing two pictures of Dilkusha as it existed when built). It was spread over a sprawling area, which is now enclosed in a specially developed park called the ‘Qutub Archaeological Village’. The purpose in building this place was stated to be that Metcalfe wanted to keep a watch on Emperor Bahadur Shah II who also had his Zafar Mahal palace in Mehrauli to spend his summer time.[3][6][12][13]

The complex was a pleasant place with several controlled streamlets of water, which led to a tank (now called the Metcalfe’s Boathouse and Dovecote). The tank was dated to the Lodi Dynasty period. This was refurbished by Metcalfe for use, for boating and swimming. Steps built from the boathouse lead to his Dilkhusha. With a retinue of servants, the immaculately kept place was stated to be an ideal setting for honeymooning couples. He also built, in "pseudo Mughal" style, a Chhatri (kiosk) or a folly with a dome and arches, and few other follies known as Garhganjs (in the form of a spiral and square stepped ziggurats).

All of the above can be seen in the Archaeological Park (a special enclosure created recently), which has strategically placed signages showing directions to the various heritage monuments. This village was created by the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), south of the Qutub Minar(see External Link on page 6 for the Map of the Archaeological Village).

The retreat had been built like a citadel with the folly (also called the only landlocked light house) in the Indo–Persian baradari style. The folly was built opposite to the remodelleld tomb of Quli Khan, surrounded by a sprawling garden. The central hall of the tomb was converted into a dining hall. Two wings were added as annexes, out of which ruins of only one is seen now. He also converted some of the old buildings around the tomb into guesthouse, staff quarters and stables.[6][14] It is also recorded that Metcalfe, the fastidious person that he was, spent lot of time at this place during his 40 years of life in Delhi. He loved this retreat and had a set of rooms made for use as a study and also lodgings for his daughter Emily to stay with him, while his wife and son lived in the formal town house in the old city. Thomas’s fondness for this place is reflected in his own words:[1][13][15][16]

The ruins of grandeur that extend for miles on every side fill it with serious reflection,” he wrote. “The palaces crumbling into dust... the myriads of vast mausoleums, every one of which was intended to convey to futurity the deathless fame of its cold inhabitant, and all of which are now passed by, unknown and unnoticed. These things cannot be looked at with indifference.

During recent restoration works carried out on the tomb, some remains of Hindu temples have been found, though the date of building the tomb is as yet unclear.[6]

Gallery

-

Metcalfe's Annexe House in ruins

-

Inside view on walls and roof of the central hall of the Dilkhusha in the former Quli Khan tomb

-

A Panoramic View of Qutub Minar from old Metcalfe house(Dilkhusha) with Guest House in the foreground on the left

-

Dilkhusa (Delight of the Heart) the country house of Metcalfe, in Mehrauli

-

Ziggaurat at entrance to Metcalfe house, Qutb complex

-

Another folly (Ziggaurat) at entrance to Qutb Archaeological village, Mehrauli

-

Ruins of Sir Thomas Metcalfe's Guest House at Dilkusha.

References

- ^ a b c d "Grand designs in Delhi: Mughal tombs converted into palatial mansions, lighthouses built in city gardens and pavilions floating on water. William Dalrymple explores the eccentric architectural legacy of colonial Delhi". The Times of India. 22 October 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ a b Ronald Vivian Smith (2005). The Delhi that no-one knows. Orient Blackswan. p. 126. ISBN 9788180280207. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Y.D.Sharma (2001). Delhi and its Neighbourhood. New Delhi: Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 49, 60, and 141. Archived from the original on 31 August 2005. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Old Secetariat". Legislative Assembly of Delhi website.

- ^ Addresses Archived 2009-05-01 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Fiona Hedger-Gourlay; Lindy Ingham; Jo Newton; Emma Tabor; Jill Worrell (13 September 2006). "Lal Kot and Siri" (pdf). pp. 4–11. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- ^ "Houses in Delhi in the 1840s". British Library: Help for Researchers. Archived from the original on 22 March 2009. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Lucy Peck (2005). Delhi - A thousand years of Building. New Delhi: Roli Books Pvt Ltd. p. 243. ISBN 81-7436-354-8. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "This time, that age". The Hindu. 28 December 2003. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ Sir Thomas Metcalfe. "Details at British Library page". British Library. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ Delhi city guide, by Eicher Goodearth Limited, Delhi Tourism. Published by Eicher Goodearth Limited, 1998. ISBN 81-900601-2-0. Page 220.

- ^ Alfred Frederick Pollock Harcourt. The New Guide to Delhi. p. 132. Retrieved 1 June 2009.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b "The last Mughal chronicler". The Business Stanadard. 11 June 2006. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Inside Delhi of Kunwari Begum and Dadi-Poti..." The Hindu. 22 May 2002. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "A case of Delhi poisoning?". The Hindu. 4 April 2004. Retrieved 3 June 2009.

- ^ "Exploring the Mehrauli Archaeological Park". Retrieved 3 June 2009.