Mutation

| Part of a series on |

| Evolutionary biology |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Genetics |

|---|

|

In biology, a mutation is the permanent alteration of the nucleotide sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA or other genetic elements. Mutations result from errors during DNA replication or other types of damage to DNA, which then may undergo error-prone repair (especially microhomology-mediated end joining[1]), or cause an error during other forms of repair,[2][3] or else may cause an error during replication (translesion synthesis). Mutations may also result from insertion or deletion of segments of DNA due to mobile genetic elements.[4][5][6] Mutations may or may not produce discernible changes in the observable characteristics (phenotype) of an organism. Mutations play a part in both normal and abnormal biological processes including: evolution, cancer, and the development of the immune system, including junctional diversity.

The genomes of RNA viruses are based on RNA rather than DNA. The RNA viral genome can be double stranded (as in DNA) or single stranded. In some of these viruses (such as the single stranded human immunodeficiency virus) replication occurs quickly and there are no mechanisms to check the genome for accuracy. This error-prone process often results in mutations.

Mutation can result in many different types of change in sequences. Mutations in genes can either have no effect, alter the product of a gene, or prevent the gene from functioning properly or completely. Mutations can also occur in nongenic regions. One study on genetic variations between different species of Drosophila suggests that, if a mutation changes a protein produced by a gene, the result is likely to be harmful, with an estimated 70 percent of amino acid polymorphisms that have damaging effects, and the remainder being either neutral or marginally beneficial.[7] Due to the damaging effects that mutations can have on genes, organisms have mechanisms such as DNA repair to prevent or correct mutations by reverting the mutated sequence back to its original state.[4]

Description

Mutations can involve the duplication of large sections of DNA, usually through genetic recombination.[8] These duplications are a major source of raw material for evolving new genes, with tens to hundreds of genes duplicated in animal genomes every million years.[9] Most genes belong to larger gene families of shared ancestry, known as homology.[10] Novel genes are produced by several methods, commonly through the duplication and mutation of an ancestral gene, or by recombining parts of different genes to form new combinations with new functions.[11][12]

Here, protein domains act as modules, each with a particular and independent function, that can be mixed together to produce genes encoding new proteins with novel properties.[13] For example, the human eye uses four genes to make structures that sense light: three for cone cell or color vision and one for rod cell or night vision; all four arose from a single ancestral gene.[14] Another advantage of duplicating a gene (or even an entire genome) is that this increases engineering redundancy; this allows one gene in the pair to acquire a new function while the other copy performs the original function.[15][16] Other types of mutation occasionally create new genes from previously noncoding DNA.[17][18]

Changes in chromosome number may involve even larger mutations, where segments of the DNA within chromosomes break and then rearrange. For example, in the Homininae, two chromosomes fused to produce human chromosome 2; this fusion did not occur in the lineage of the other apes, and they retain these separate chromosomes.[19] In evolution, the most important role of such chromosomal rearrangements may be to accelerate the divergence of a population into new species by making populations less likely to interbreed, thereby preserving genetic differences between these populations.[20]

Sequences of DNA that can move about the genome, such as transposons, make up a major fraction of the genetic material of plants and animals, and may have been important in the evolution of genomes.[21] For example, more than a million copies of the Alu sequence are present in the human genome, and these sequences have now been recruited to perform functions such as regulating gene expression.[22] Another effect of these mobile DNA sequences is that when they move within a genome, they can mutate or delete existing genes and thereby produce genetic diversity.[5]

Nonlethal mutations accumulate within the gene pool and increase the amount of genetic variation.[23] The abundance of some genetic changes within the gene pool can be reduced by natural selection, while other "more favorable" mutations may accumulate and result in adaptive changes.

For example, a butterfly may produce offspring with new mutations. The majority of these mutations will have no effect; but one might change the color of one of the butterfly's offspring, making it harder (or easier) for predators to see. If this color change is advantageous, the chance of this butterfly's surviving and producing its own offspring are a little better, and over time the number of butterflies with this mutation may form a larger percentage of the population.

Neutral mutations are defined as mutations whose effects do not influence the fitness of an individual. These can accumulate over time due to genetic drift. It is believed that the overwhelming majority of mutations have no significant effect on an organism's fitness.[citation needed] Also, DNA repair mechanisms are able to mend most changes before they become permanent mutations, and many organisms have mechanisms for eliminating otherwise-permanently mutated somatic cells.

Beneficial mutations can improve reproductive success.

Causes

Four classes of mutations are (1) spontaneous mutations (molecular decay), (2) mutations due to error-prone replication bypass of naturally occurring DNA damage (also called error-prone translesion synthesis), (3) errors introduced during DNA repair, and (4) induced mutations caused by mutagens. Scientists may also deliberately introduce mutant sequences through DNA manipulation for the sake of scientific experimentation.

Spontaneous mutation

Spontaneous mutations on the molecular level can be caused by:[24]

- Tautomerism — A base is changed by the repositioning of a hydrogen atom, altering the hydrogen bonding pattern of that base, resulting in incorrect base pairing during replication.

- Depurination — Loss of a purine base (A or G) to form an apurinic site (AP site).

- Deamination — Hydrolysis changes a normal base to an atypical base containing a keto group in place of the original amine group. Examples include C → U and A → HX (hypoxanthine), which can be corrected by DNA repair mechanisms; and 5MeC (5-methylcytosine) → T, which is less likely to be detected as a mutation because thymine is a normal DNA base.

- Slipped strand mispairing — Denaturation of the new strand from the template during replication, followed by renaturation in a different spot ("slipping"). This can lead to insertions or deletions.

Error-prone replication bypass

There is increasing evidence that the majority of spontaneously arising mutations are due to error-prone replication (translesion synthesis) past DNA damage in the template strand. Naturally occurring oxidative DNA damages arise at least 10,000 times per cell per day in humans and 50,000 times or more per cell per day in rats.[25] In mice, the majority of mutations are caused by translesion synthesis.[26] Likewise, in yeast, Kunz et al.[27] found that more than 60% of the spontaneous single base pair substitutions and deletions were caused by translesion synthesis.

Errors introduced during DNA repair

Although naturally occurring double-strand breaks occur at a relatively low frequency in DNA, their repair often causes mutation. Non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) is a major pathway for repairing double-strand breaks. NHEJ involves removal of a few nucleotides to allow somewhat inaccurate alignment of the two ends for rejoining followed by addition of nucleotides to fill in gaps. As a consequence, NHEJ often introduces mutations.[28]

Induced mutation

Induced mutations on the molecular level can be caused by:-

- Chemicals

- Hydroxylamine

- Base analogs (e.g., Bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU))

- Alkylating agents (e.g., N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)). These agents can mutate both replicating and non-replicating DNA. In contrast, a base analog can mutate the DNA only when the analog is incorporated in replicating the DNA. Each of these classes of chemical mutagens has certain effects that then lead to transitions, transversions, or deletions.

- Agents that form DNA adducts (e.g., ochratoxin A)[30]

- DNA intercalating agents (e.g., ethidium bromide)

- DNA crosslinkers

- Oxidative damage

- Nitrous acid converts amine groups on A and C to diazo groups, altering their hydrogen bonding patterns, which leads to incorrect base pairing during replication.

- Radiation

- Ultraviolet light (UV) (non-ionizing radiation). Two nucleotide bases in DNA—cytosine and thymine—are most vulnerable to radiation that can change their properties. UV light can induce adjacent pyrimidine bases in a DNA strand to become covalently joined as a pyrimidine dimer. UV radiation, in particular longer-wave UVA, can also cause oxidative damage to DNA.[31]

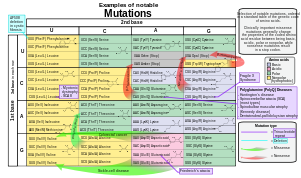

Classification of mutation types

By effect on structure

The sequence of a gene can be altered in a number of ways. Gene mutations have varying effects on health depending on where they occur and whether they alter the function of essential proteins. Mutations in the structure of genes can be classified as:

- Small-scale mutations, such as those affecting a small gene in one or a few nucleotides, including:

- Substitution mutations, often caused by chemicals or malfunction of DNA replication, exchange a single nucleotide for another.[33] These changes are classified as transitions or transversions.[34] Most common is the transition that exchanges a purine for a purine (A ↔ G) or a pyrimidine for a pyrimidine, (C ↔ T). A transition can be caused by nitrous acid, base mis-pairing, or mutagenic base analogs such as BrdU. Less common is a transversion, which exchanges a purine for a pyrimidine or a pyrimidine for a purine (C/T ↔ A/G). An example of a transversion is the conversion of adenine (A) into a cytosine (C). A point mutation can be reversed by another point mutation, in which the nucleotide is changed back to its original state (true reversion) or by second-site reversion (a complementary mutation elsewhere that results in regained gene functionality). Point mutations that occur within the protein coding region of a gene may be classified into three kinds, depending upon what the erroneous codon codes for:

- Silent mutations, which code for the same (or a sufficiently similar) amino acid.

- Missense mutations, which code for a different amino acid.

- Nonsense mutations, which code for a stop codon and can truncate the protein.

- Insertions add one or more extra nucleotides into the DNA. They are usually caused by transposable elements, or errors during replication of repeating elements. Insertions in the coding region of a gene may alter splicing of the mRNA (splice site mutation), or cause a shift in the reading frame (frameshift), both of which can significantly alter the gene product. Insertions can be reversed by excision of the transposable element.

- Deletions remove one or more nucleotides from the DNA. Like insertions, these mutations can alter the reading frame of the gene. In general, they are irreversible: Though exactly the same sequence might in theory be restored by an insertion, transposable elements able to revert a very short deletion (say 1–2 bases) in any location either are highly unlikely to exist or do not exist at all.

- Substitution mutations, often caused by chemicals or malfunction of DNA replication, exchange a single nucleotide for another.[33] These changes are classified as transitions or transversions.[34] Most common is the transition that exchanges a purine for a purine (A ↔ G) or a pyrimidine for a pyrimidine, (C ↔ T). A transition can be caused by nitrous acid, base mis-pairing, or mutagenic base analogs such as BrdU. Less common is a transversion, which exchanges a purine for a pyrimidine or a pyrimidine for a purine (C/T ↔ A/G). An example of a transversion is the conversion of adenine (A) into a cytosine (C). A point mutation can be reversed by another point mutation, in which the nucleotide is changed back to its original state (true reversion) or by second-site reversion (a complementary mutation elsewhere that results in regained gene functionality). Point mutations that occur within the protein coding region of a gene may be classified into three kinds, depending upon what the erroneous codon codes for:

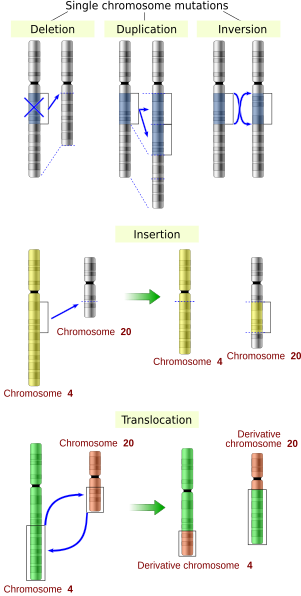

- Large-scale mutations in chromosomal structure, including:

- Amplifications (or gene duplications) leading to multiple copies of all chromosomal regions, increasing the dosage of the genes located within them.

- Deletions of large chromosomal regions, leading to loss of the genes within those regions.

- Mutations whose effect is to juxtapose previously separate pieces of DNA, potentially bringing together separate genes to form functionally distinct fusion genes (e.g., bcr-abl). These include:

- Chromosomal translocations: interchange of genetic parts from nonhomologous chromosomes.

- Interstitial deletions: an intra-chromosomal deletion that removes a segment of DNA from a single chromosome, thereby apposing previously distant genes. For example, cells isolated from a human astrocytoma, a type of brain tumor, were found to have a chromosomal deletion removing sequences between the Fused in Glioblastoma (FIG) gene and the receptor tyrosine kinase (ROS), producing a fusion protein (FIG-ROS). The abnormal FIG-ROS fusion protein has constitutively active kinase activity that causes oncogenic transformation (a transformation from normal cells to cancer cells).

- Chromosomal inversions: reversing the orientation of a chromosomal segment.

- Loss of heterozygosity: loss of one allele, either by a deletion or a genetic recombination event, in an organism that previously had two different alleles.

By effect on function

- Loss-of-function mutations, also called inactivating mutations, result in the gene product having less or no function (being partially or wholly inactivated). When the allele has a complete loss of function (null allele), it is often called an amorphic mutation in the Muller's morphs schema. Phenotypes associated with such mutations are most often recessive. Exceptions are when the organism is haploid, or when the reduced dosage of a normal gene product is not enough for a normal phenotype (this is called haploinsufficiency).

- Gain-of-function mutations, also called activating mutations, change the gene product such that its effect gets stronger (enhanced activation) or even is superseded by a different and abnormal function. When the new allele is created, a heterozygote containing the newly created allele as well as the original will express the new allele; genetically this defines the mutations as dominant phenotypes. Often called a neomorphic mutation.[35]

- Dominant negative mutations (also called antimorphic mutations) have an altered gene product that acts antagonistically to the wild-type allele. These mutations usually result in an altered molecular function (often inactive) and are characterized by a dominant or semi-dominant phenotype. In humans, dominant negative mutations have been implicated in cancer (e.g., mutations in genes p53,[36] ATM,[37] CEBPA[38] and PPARgamma[39]). Marfan syndrome is caused by mutations in the FBN1 gene, located on chromosome 15, which encodes fibrillin-1, a glycoprotein component of the extracellular matrix.[40] Marfan syndrome is also an example of dominant negative mutation and haploinsufficiency.[41][42]

- Lethal mutations are mutations that lead to the death of the organisms that carry the mutations.

- A back mutation or reversion is a point mutation that restores the original sequence and hence the original phenotype.[43]

By effect on fitness

In applied genetics, it is usual to speak of mutations as either harmful or beneficial.

- A harmful, or deleterious, mutation decreases the fitness of the organism.

- A beneficial, or advantageous mutation increases the fitness of the organism. Mutations that promotes traits that are desirable, are also called beneficial. In theoretical population genetics, it is more usual to speak of mutations as deleterious or advantageous than harmful or beneficial.

- A neutral mutation has no harmful or beneficial effect on the organism. Such mutations occur at a steady rate, forming the basis for the molecular clock. In the neutral theory of molecular evolution, neutral mutations provide genetic drift as the basis for most variation at the molecular level.

- A nearly neutral mutation is a mutation that may be slightly deleterious or advantageous, although most nearly neutral mutations are slightly deleterious.

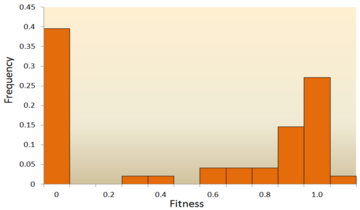

Distribution of fitness effects

Attempts have been made to infer the distribution of fitness effects (DFE) using mutagenesis experiments and theoretical models applied to molecular sequence data. DFE, as used to determine the relative abundance of different types of mutations (i.e., strongly deleterious, nearly neutral or advantageous), is relevant to many evolutionary questions, such as the maintenance of genetic variation,[44] the rate of genomic decay,[45] the maintenance of outcrossing sexual reproduction as opposed to inbreeding[46] and the evolution of sex and genetic recombination.[47] In summary, the DFE plays an important role in predicting evolutionary dynamics.[48][49] A variety of approaches have been used to study the DFE, including theoretical, experimental and analytical methods.

- Mutagenesis experiment: The direct method to investigate the DFE is to induce mutations and then measure the mutational fitness effects, which has already been done in viruses, bacteria, yeast, and Drosophila. For example, most studies of the DFE in viruses used site-directed mutagenesis to create point mutations and measure relative fitness of each mutant.[50][51][52][53] In Escherichia coli, one study used transposon mutagenesis to directly measure the fitness of a random insertion of a derivative of Tn10.[54] In yeast, a combined mutagenesis and deep sequencing approach has been developed to generate high-quality systematic mutant libraries and measure fitness in high throughput.[55] However, given that many mutations have effects too small to be detected[56] and that mutagenesis experiments can detect only mutations of moderately large effect; DNA sequence data analysis can provide valuable information about these mutations.

- Molecular sequence analysis: With rapid development of DNA sequencing technology, an enormous amount of DNA sequence data is available and even more is forthcoming in the future. Various methods have been developed to infer the DFE from DNA sequence data.[57][58][59][60] By examining DNA sequence differences within and between species, we are able to infer various characteristics of the DFE for neutral, deleterious and advantageous mutations.[23] To be specific, the DNA sequence analysis approach allows us to estimate the effects of mutations with very small effects, which are hardly detectable through mutagenesis experiments.

One of the earliest theoretical studies of the distribution of fitness effects was done by Motoo Kimura, an influential theoretical population geneticist. His neutral theory of molecular evolution proposes that most novel mutations will be highly deleterious, with a small fraction being neutral.[61][62] Hiroshi Akashi more recently proposed a bimodal model for the DFE, with modes centered around highly deleterious and neutral mutations.[63] Both theories agree that the vast majority of novel mutations are neutral or deleterious and that advantageous mutations are rare, which has been supported by experimental results. One example is a study done on the DFE of random mutations in vesicular stomatitis virus.[50] Out of all mutations, 39.6% were lethal, 31.2% were non-lethal deleterious, and 27.1% were neutral. Another example comes from a high throughput mutagenesis experiment with yeast.[55] In this experiment it was shown that the overall DFE is bimodal, with a cluster of neutral mutations, and a broad distribution of deleterious mutations.

Though relatively few mutations are advantageous, those that are play an important role in evolutionary changes.[64] Like neutral mutations, weakly selected advantageous mutations can be lost due to random genetic drift, but strongly selected advantageous mutations are more likely to be fixed. Knowing the DFE of advantageous mutations may lead to increased ability to predict the evolutionary dynamics. Theoretical work on the DFE for advantageous mutations has been done by John H. Gillespie[65] and H. Allen Orr.[66] They proposed that the distribution for advantageous mutations should be exponential under a wide range of conditions, which, in general, has been supported by experimental studies, at least for strongly selected advantageous mutations.[67][68][69]

In general, it is accepted that the majority of mutations are neutral or deleterious, with rare mutations being advantageous; however, the proportion of types of mutations varies between species. This indicates two important points: first, the proportion of effectively neutral mutations is likely to vary between species, resulting from dependence on effective population size; second, the average effect of deleterious mutations varies dramatically between species.[23] In addition, the DFE also differs between coding regions and noncoding regions, with the DFE of noncoding DNA containing more weakly selected mutations.[23]

By impact on protein sequence

- A frameshift mutation is a mutation caused by insertion or deletion of a number of nucleotides that is not evenly divisible by three from a DNA sequence. Due to the triplet nature of gene expression by codons, the insertion or deletion can disrupt the reading frame, or the grouping of the codons, resulting in a completely different translation from the original.[70] The earlier in the sequence the deletion or insertion occurs, the more altered the protein produced is.

- In contrast, any insertion or deletion that is evenly divisible by three is termed an in-frame mutation

- A nonsense mutation is a point mutation in a sequence of DNA that results in a premature stop codon, or a nonsense codon in the transcribed mRNA, and possibly a truncated, and often nonfunctional protein product. (See Stop codon.)

- Missense mutations or nonsynonymous mutations are types of point mutations where a single nucleotide is changed to cause substitution of a different amino acid. This in turn can render the resulting protein nonfunctional. Such mutations are responsible for diseases such as Epidermolysis bullosa, sickle-cell disease, and SOD1-mediated ALS.[71]

- A neutral mutation is a mutation that occurs in an amino acid codon that results in the use of a different, but chemically similar, amino acid. The similarity between the two is enough that little or no change is often rendered in the protein. For example, a change from AAA to AGA will encode arginine, a chemically similar molecule to the intended lysine.

- Silent mutations are mutations that do not result in a change to the amino acid sequence of a protein, unless the changed amino acid is sufficiently similar to the original. They may occur in a region that does not code for a protein, or they may occur within a codon in a manner that does not alter the final amino acid sequence. The phrase silent mutation is often used interchangeably with the phrase synonymous mutation; however, synonymous mutations are a subcategory of the former, occurring only within exons (and necessarily exactly preserving the amino acid sequence of the protein). Synonymous mutations occur due to the degenerate nature of the genetic code.

By inheritance

In multicellular organisms with dedicated reproductive cells, mutations can be subdivided into germline mutations, which can be passed on to descendants through their reproductive cells, and somatic mutations (also called acquired mutations),[72] which involve cells outside the dedicated reproductive group and which are not usually transmitted to descendants.

A germline mutation gives rise to a constitutional mutation in the offspring, that is, a mutation that is present in every cell. A constitutional mutation can also occur very soon after fertilisation, or continue from a previous constitutional mutation in a parent.[73]

The distinction between germline and somatic mutations is important in animals that have a dedicated germline to produce reproductive cells. However, it is of little value in understanding the effects of mutations in plants, which lack dedicated germline. The distinction is also blurred in those animals that reproduce asexually through mechanisms such as budding, because the cells that give rise to the daughter organisms also give rise to that organism's germline. A new germline mutation that was not inherited from either parent is called a de novo mutation.

Diploid organisms (e.g., humans) contain two copies of each gene—a paternal and a maternal allele. Based on the occurrence of mutation on each chromosome, we may classify mutations into three types.

- A heterozygous mutation is a mutation of only one allele.

- A homozygous mutation is an identical mutation of both the paternal and maternal alleles.

- Compound heterozygous mutations or a genetic compound consists of two different mutations in the paternal and maternal alleles.[74]

A wild type or homozygous non-mutated organism is one in which neither allele is mutated.

Special classes

- Conditional mutation is a mutation that has wild-type (or less severe) phenotype under certain "permissive" environmental conditions and a mutant phenotype under certain "restrictive" conditions. For example, a temperature-sensitive mutation can cause cell death at high temperature (restrictive condition), but might have no deleterious consequences at a lower temperature (permissive condition).

- Replication timing quantitative trait loci affects DNA replication.

Nomenclature

In order to categorize a mutation as such, the "normal" sequence must be obtained from the DNA of a "normal" or "healthy" organism (as opposed to a "mutant" or "sick" one), it should be identified and reported; ideally, it should be made publicly available for a straightforward nucleotide-by-nucleotide comparison, and agreed upon by the scientific community or by a group of expert geneticists and biologists, who have the responsibility of establishing the standard or so-called "consensus" sequence. This step requires a tremendous scientific effort. (See DNA sequencing.) Once the consensus sequence is known, the mutations in a genome can be pinpointed, described, and classified. The committee of the Human Genome Variation Society (HGVS) has developed the standard human sequence variant nomenclature,[75] which should be used by researchers and DNA diagnostic centers to generate unambiguous mutation descriptions. In principle, this nomenclature can also be used to describe mutations in other organisms. The nomenclature specifies the type of mutation and base or amino acid changes.

- Nucleotide substitution (e.g., 76A>T) — The number is the position of the nucleotide from the 5' end; the first letter represents the wild-type nucleotide, and the second letter represents the nucleotide that replaced the wild type. In the given example, the adenine at the 76th position was replaced by a thymine.

- If it becomes necessary to differentiate between mutations in genomic DNA, mitochondrial DNA, and RNA, a simple convention is used. For example, if the 100th base of a nucleotide sequence mutated from G to C, then it would be written as g.100G>C if the mutation occurred in genomic DNA, m.100G>C if the mutation occurred in mitochondrial DNA, or r.100g>c if the mutation occurred in RNA. Note that, for mutations in RNA, the nucleotide code is written in lower case.

- Amino acid substitution (e.g., D111E) — The first letter is the one letter code of the wild-type amino acid, the number is the position of the amino acid from the N-terminus, and the second letter is the one letter code of the amino acid present in the mutation. Nonsense mutations are represented with an X for the second amino acid (e.g. D111X).

- Amino acid deletion (e.g., ΔF508) — The Greek letter Δ (delta) indicates a deletion. The letter refers to the amino acid present in the wild type and the number is the position from the N terminus of the amino acid were it to be present as in the wild type.

Mutation rates

Mutation rates vary substantially across species, and the evolutionary forces that generally determine mutation are the subject of ongoing investigation.

Harmful mutations

Changes in DNA caused by mutation can cause errors in protein sequence, creating partially or completely non-functional proteins. Each cell, in order to function correctly, depends on thousands of proteins to function in the right places at the right times. When a mutation alters a protein that plays a critical role in the body, a medical condition can result. A condition caused by mutations in one or more genes is called a Sheik disorder. Some mutations alter a gene's DNA base sequence but do not change the function of the protein made by the gene. One study on the comparison of genes between different species of Drosophila suggests that if a mutation does change a protein, this will probably be harmful, with an estimated 70 percent of amino acid polymorphisms having damaging effects, and the remainder being either neutral or weakly beneficial.]][7] Studies have shown that only 7% of point mutations in noncoding DNA of yeast are deleterious and 12% in coding DNA are deleterious. The rest of the mutations are either neutral or slightly beneficial.[76]

If a mutation is present in a germ cell, it can give rise to offspring that carries the mutation in all of its cells. This is the case in hereditary diseases. In particular, if there is a mutation in a DNA repair gene within a germ cell, humans carrying such germline mutations may have an increased risk of cancer. A list of 34 such germline mutations is given in the article DNA repair-deficiency disorder. An example of one is albinism, a mutation that occurs in the OCA1 or OCA2 gene. Individuals with this disorder are more prone to many types of cancers, other disorders and have impaired vision. On the other hand, a mutation may occur in a somatic cell of an organism. Such mutations will be present in all descendants of this cell within the same organism, and certain mutations can cause the cell to become malignant, and, thus, cause cancer.[77]

A DNA damage can cause an error when the DNA is replicated, and this error of replication can cause a gene mutation that, in turn, could cause a genetic disorder. DNA damages are repaired by the DNA repair system of the cell. Each cell has a number of pathways through which enzymes recognize and repair damages in DNA. Because DNA can be damaged in many ways, the process of DNA repair is an important way in which the body protects itself from disease. Once DNA damage has given rise to a mutation, the mutation cannot be repaired. DNA repair pathways can only recognize and act on "abnormal" structures in the DNA. Once a mutation occurs in a gene sequence it then has normal DNA structure and cannot be repaired.

Beneficial mutations

Although mutations that cause changes in protein sequences can be harmful to an organism, on occasions the effect may be positive in a given environment. In this case, the mutation may enable the mutant organism to withstand particular environmental stresses better than wild-type organisms, or reproduce more quickly. In these cases a mutation will tend to become more common in a population through natural selection.

For example, a specific 32 base pair deletion in human CCR5 (CCR5-Δ32) confers HIV resistance to homozygotes and delays AIDS onset in heterozygotes.[78] One possible explanation of the etiology of the relatively high frequency of CCR5-Δ32 in the European population is that it conferred resistance to the bubonic plague in mid-14th century Europe. People with this mutation were more likely to survive infection; thus its frequency in the population increased.[79] This theory could explain why this mutation is not found in Southern Africa, which remained untouched by bubonic plague. A newer theory suggests that the selective pressure on the CCR5 Delta 32 mutation was caused by smallpox instead of the bubonic plague.[80]

An example of a harmful mutation is sickle-cell disease, a blood disorder in which the body produces an abnormal type of the oxygen-carrying substance hemoglobin in the red blood cells. One-third of all indigenous inhabitants of Sub-Saharan Africa carry the gene, because, in areas where malaria is common, there is a survival value in carrying only a single sickle-cell gene (sickle cell trait).[81] Those with only one of the two alleles of the sickle-cell disease are more resistant to malaria, since the infestation of the malaria Plasmodium is halted by the sickling of the cells that it infests.

Prion mutations

Prions are proteins and do not contain genetic material. However, prion replication has been shown to be subject to mutation and natural selection just like other forms of replication.[82] The human gene PRNP codes for the major prion protein, PrP, and is subject to mutations that can give rise to disease-causing prions.

Somatic mutations

A change in the genetic structure that is not inherited from a parent, and also not passed to offspring, is called a somatic cell genetic mutation or acquired mutation.[72]

Cells with heterozygous mutations (one good copy of gene and one mutated copy) may function normally with the unmutated copy until the good copy has been spontaneously somatically mutated. This kind of mutation happens all the time in living organisms, but it is difficult to measure the rate. Measuring this rate is important in predicting the rate at which people may develop cancer.[83]

Point mutations may arise from spontaneous mutations that occur during DNA replication. The rate of mutation may be increased by mutagens. Mutagens can be physical, such as radiation from UV rays, X-rays or extreme heat, or chemical (molecules that misplace base pairs or disrupt the helical shape of DNA). Mutagens associated with cancers are often studied to learn about cancer and its prevention.

See also

References

- ^ Sharma S, Javadekar SM, Pandey M, Srivastava M, Kumari R, Raghavan SC (2015). "Homology and enzymatic requirements of microhomology-dependent alternative end joining". Cell Death Dis. 6: e1697. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.58. PMC 4385936. PMID 25789972.

- ^ Chen J, Miller BF, Furano AV (2014). "Repair of naturally occurring mismatches can induce mutations in flanking DNA". Elife. 3: e02001. doi:10.7554/elife.02001. PMC 3999860. PMID 24843013.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Rodgers K, McVey M (2016). "Error-Prone Repair of DNA Double-Strand Breaks". J. Cell. Physiol. 231 (1): 15–24. doi:10.1002/jcp.25053. PMID 26033759.

- ^ a b Bertram, John S. (December 2000). "The molecular biology of cancer". Molecular Aspects of Medicine. 21 (6). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 167–223. doi:10.1016/S0098-2997(00)00007-8. ISSN 0098-2997. PMID 11173079.

- ^ a b Aminetzach, Yael T.; Macpherson, J. Michael; Petrov, Dmitri A. (29 July 2005). "Pesticide Resistance via Transposition-Mediated Adaptive Gene Truncation in Drosophila". Science. 309 (5735). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 764–767. Bibcode:2005Sci...309..764A. doi:10.1126/science.1112699. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 16051794.

- ^ Burrus, Vincent; Waldor, Matthew K. (June 2004). "Shaping bacterial genomes with integrative and conjugative elements". Research in Microbiology. 155 (5). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 376–386. doi:10.1016/j.resmic.2004.01.012. ISSN 0923-2508. PMID 15207870.

- ^ a b Sawyer, Stanley A.; Parsch, John; Zhi Zhang; et al. (17 April 2007). "Prevalence of positive selection among nearly neutral amino acid replacements in Drosophila". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (16). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 6504–6510. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.6504S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0701572104. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1871816. PMID 17409186.

- ^ Hastings, P. J.; Lupski, James R.; Rosenberg, Susan M.; et al. (August 2009). "Mechanisms of change in gene copy number". Nature Reviews Genetics. 10 (8). London: Nature Publishing Group: 551–564. doi:10.1038/nrg2593. ISSN 1471-0056. PMC 2864001. PMID 19597530.

- ^ Carroll, Grenier & Weatherbee 2005

- ^ Harrison, Paul M.; Gerstein, Mark (17 May 2002). "Studying Genomes Through the Aeons: Protein Families, Pseudogenes and Proteome Evolution". Journal of Molecular Biology. 318 (5). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 1155–1174. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(02)00109-2. ISSN 0022-2836. PMID 12083509.

- ^ Orengo, Christine A.; Thornton, Janet M. (July 2005). "Protein families and their evolution—a structural perspective". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 74. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews: 867–900. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.74.082803.133029. ISSN 0066-4154. PMID 15954844.

- ^ Manyuan Long; Betrán, Esther; Thornton, Kevin; et al. (November 2003). "The origin of new genes: glimpses from the young and old". Nature Reviews Genetics. 4 (11). London: Nature Publishing Group: 865–875. doi:10.1038/nrg1204. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 14634634.

- ^ Minglei Wang; Caetano-Anollés, Gustavo (14 January 2009). "The Evolutionary Mechanics of Domain Organization in Proteomes and the Rise of Modularity in the Protein World". Structure. 17 (1). Cambridge, MA: Cell Press: 66–78. doi:10.1016/j.str.2008.11.008. ISSN 0969-2126. PMID 19141283.

- ^ Bowmaker, James K. (May 1998). "Evolution of colour vision in vertebrates". Eye. 12 (Pt 3b). London: Nature Publishing Group: 541–547. doi:10.1038/eye.1998.143. ISSN 0950-222X. PMID 9775215.

- ^ Gregory, T. Ryan; Hebert, Paul D. N. (April 1999). "The Modulation of DNA Content: Proximate Causes and Ultimate Consequences". Genome Research. 9 (4). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 317–324. doi:10.1101/gr.9.4.317. ISSN 1088-9051. PMID 10207154. Retrieved 1 October 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|doi_brokendate=ignored (|doi-broken-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Hurles, Matthew (13 July 2004). "Gene Duplication: The Genomic Trade in Spare Parts". PLOS Biology. 2 (7). San Francisco, CA: Public Library of Science: E206. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020206. ISSN 1545-7885. PMC 449868. PMID 15252449.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Na Liu; Okamura, Katsutomo; Tyler, David M.; et al. (October 2008). "The evolution and functional diversification of animal microRNA genes". Cell Research. 18 (10). London: Nature Publishing Group on behalf of the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences: 985–996. doi:10.1038/cr.2008.278. ISSN 1001-0602. PMC 2712117. PMID 18711447.

- ^ Siepel, Adam (October 2009). "Darwinian alchemy: Human genes from noncoding DNA". Genome Research. 19 (10). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 1693–1695. doi:10.1101/gr.098376.109. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 2765273. PMID 19797681.

- ^ Jianzhi Zhang; Xiaoxia Wang; Podlaha, Ondrej (May 2004). "Testing the Chromosomal Speciation Hypothesis for Humans and Chimpanzees". Genome Research. 14 (5). Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: 845–851. doi:10.1101/gr.1891104. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 479111. PMID 15123584.

- ^ Ayala, Francisco J.; Coluzzi, Mario (3 May 2005). "Chromosome speciation: Humans, Drosophila, and mosquitoes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (Suppl 1). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 6535–6542. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6535A. doi:10.1073/pnas.0501847102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1131864. PMID 15851677.

- ^ Hurst, Gregory D. D.; Werren, John H. (August 2001). "The role of selfish genetic elements in eukaryotic evolution". Nature Reviews Genetics. 2 (8). London: Nature Publishing Group: 597–606. doi:10.1038/35084545. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 11483984.

- ^ Häsler, Julien; Strub, Katharina (November 2006). "Alu elements as regulators of gene expression". Nucleic Acids Research. 34 (19). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press: 5491–5497. doi:10.1093/nar/gkl706. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 1636486. PMID 17020921.

- ^ a b c d Eyre-Walker, Adam; Keightley, Peter D. (August 2007). "The distribution of fitness effects of new mutations" (PDF). Nature Reviews Genetics. 8 (8). London: Nature Publishing Group: 610–618. doi:10.1038/nrg2146. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 17637733. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Montelone, Beth A. (1998). "Mutation, Mutagens, and DNA Repair". www-personal.ksu.edu. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ^ Bernstein C, Prasad AR, Nfonsam V, Bernstein H. (2013). DNA Damage, DNA Repair and Cancer, New Research Directions in DNA Repair, Prof. Clark Chen (Ed.), ISBN 978-953-51-1114-6, InTech, http://www.intechopen.com/books/new-research-directions-in-dna-repair/dna-damage-dna-repair-and-cancer

- ^ Stuart, Gregory R.; Oda, Yoshimitsu; de Boer, Johan G.; Glickman, Barry W. (March 2000). "Mutation Frequency and Specificity With Age in Liver, Bladder and Brain of lacI Transgenic Mice". Genetics. 154 (3). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 1291–1300. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1460990. PMID 10757770. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Kunz, Bernard A.; Ramachandran, Karthikeyan; Vonarx, Edward J. (April 1998). "DNA Sequence Analysis of Spontaneous Mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Genetics. 148 (4). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 1491–1505. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1460101. PMID 9560369. Retrieved 3 October 2015.

- ^ Lieber, Michael R. (July 2010). "The Mechanism of Double-Strand DNA Break Repair by the Nonhomologous DNA End-Joining Pathway". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 79. Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews: 181–211. doi:10.1146/annurev.biochem.052308.093131. ISSN 0066-4154. PMC 3079308. PMID 20192759.

- ^ Created from PDB 1JDG

- ^ Pfohl-Leszkowicz, Annie; Manderville, Richard A. (January 2007). "Ochratoxin A: An overview on toxicity and carcinogenicity in animals and humans". Molecular Nutrition & Food Research. 51 (1). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell: 61–99. doi:10.1002/mnfr.200600137. ISSN 1613-4125. PMID 17195275.

- ^ Kozmin, Stanislav; Slezak, Guenaelle; Reynaud-Angelin, Anne; et al. (20 September 2005). "UVA radiation is highly mutagenic in cells that are unable to repair 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102 (38). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 13538–13543. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10213538K. doi:10.1073/pnas.0504497102. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 1224634. PMID 16157879.

- ^ References for the image are found in Wikimedia Commons page at: Commons:File:Notable mutations.svg#References.

- ^ Freese, Ernst (15 April 1959). "The difference between Spontaneous and Base-Analogue Induced Mutations of Phage T4". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 45 (4). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 622–633. doi:10.1073/pnas.45.4.622. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 222607. PMID 16590424.

- ^ Freese, Ernst (June 1959). "The specific mutagenic effect of base analogues on Phage T4". Journal of Molecular Biology. 1 (2). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 87–105. doi:10.1016/S0022-2836(59)80038-3. ISSN 0022-2836.

- ^ McClean, Phillip (1999). "Types of Mutations". Genes and Mutations. Course material from PLSC 431/631 - Intermediate Genetics.

- ^ Goh, Amanda M.; Coffill, Cynthia R; Lane, David P. (January 2011). "The role of mutant p53 in human cancer". The Journal of Pathology. 223 (2). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons: 116–126. doi:10.1002/path.2784. ISSN 0022-3417. PMID 21125670.

- ^ Chenevix-Trench, Georgia; Spurdle, Amanda B.; Gatei, Magtouf; et al. (6 February 2002). "Dominant Negative ATM Mutations in Breast Cancer Families". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 94 (3). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press: 205–215. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.3.205. ISSN 0027-8874. PMID 11830610.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Paz-Priel, Ido; Friedman, Alan (2011). "C/EBPα dysregulation in AML and ALL". Critical Reviews in Oncogenesis. 16 (1–2). Redding, CT: Begell House: 93–102. doi:10.1615/critrevoncog.v16.i1-2.90. ISSN 0893-9675. PMC 3243939. PMID 22150310.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|subscription=ignored (|url-access=suggested) (help) - ^ Capaccio, Daniela; Ciccodicola, Alfredo; Sabatino, Lina; et al. (June 2010). "A novel germline mutation in Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ gene associated with large intestine polyp formation and dyslipidemia". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1802 (6). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 572–581. doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.01.012. ISSN 0925-4439. PMID 20123124.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ McKusick, Victor A. (25 July 1991). "The defect in Marfan syndrome". Nature. 352 (6333). London: Nature Publishing Group: 279–281. Bibcode:1991Natur.352..279M. doi:10.1038/352279a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 1852198.

- ^ Judge, Daniel P.; Biery, Nancy J.; Keene, Douglas R.; et al. (15 July 2004). "Evidence for a critical contribution of haploinsufficiency in the complex pathogenesis of Marfan syndrome". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 114 (2). Ann Arbor, MI: American Society for Clinical Investigation: 172–181. doi:10.1172/JCI20641. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 449744. PMID 15254584.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|name-list-format=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help) - ^ Judge, Daniel P.; Dietz, Harry C. (3 December 2005). "Marfan's syndrome". The Lancet. 366 (9501). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 1965–1976. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67789-6. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 1513064. PMID 16325700.

- ^ Ellis, Nathan A.; Ciocci, Susan; German, James (February 2001). "Back mutation can produce phenotype reversion in Bloom syndrome somatic cells". Human Genetics. 108 (2). Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag: 167–173. doi:10.1007/s004390000447. ISSN 0340-6717. PMID 11281456.

- ^ Charlesworth, Deborah; Charlesworth, Brian; Morgan, Martin T. (December 1995). "The Pattern of Neutral Molecular Variation Under the Background Selection Model". Genetics. 141 (4). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 1619–1632. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1206892. PMID 8601499.

- ^ Loewe, Laurence (April 2006). "Quantifying the genomic decay paradox due to Muller's ratchet in human mitochondrial DNA". Genetical Research. 87 (2). London; New York: Cambridge University Press: 133–159. doi:10.1017/S0016672306008123. ISSN 0016-6723. PMID 16709275.

- ^ Bernstein, H; Hopf, FA; Michod, RE (1987). "The molecular basis of the evolution of sex". Adv Genet. 24: 323–70. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7. PMID 3324702.

- ^ Peck, Joel R.; Barreau, Guillaume; Heath, Simon C. (April 1997). "Imperfect Genes, Fisherian Mutation and the Evolution of Sex". Genetics. 145 (4). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 1171–1199. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1207886. PMID 9093868.

- ^ Keightley, Peter D.; Lynch, Michael (March 2003). "Toward a Realistic Model of Mutations Affecting Fitness". Evolution. 57 (3). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons for the Society for the Study of Evolution: 683–689. doi:10.1554/0014-3820(2003)057[0683:tarmom]2.0.co;2. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 3094781. PMID 12703958.

- ^ Barton, Nicholas H.; Keightley, Peter D. (January 2002). "Understanding quantitative genetic variation". Nature Reviews Genetics. 3 (1). London: Nature Publishing Group: 11–21. doi:10.1038/nrg700. ISSN 1471-0056. PMID 11823787.

- ^ a b c Sanjuán, Rafael; Moya, Andrés; Elena, Santiago F. (1 June 2004). "The distribution of fitness effects caused by single-nucleotide substitutions in an RNA virus". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101 (22). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 8396–8401. doi:10.1073/pnas.0400146101. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 420405. PMID 15159545.

- ^ Carrasco, Purificación; de la Iglesia, Francisca; Elena, Santiago F. (December 2007). "Distribution of Fitness and Virulence Effects Caused by Single-Nucleotide Substitutions in Tobacco Etch Virus". Journal of Virology. 81 (23). Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology: 12979–12984. doi:10.1128/JVI.00524-07. ISSN 0022-538X. PMC 2169111. PMID 17898073.

- ^ Sanjuán, Rafael (27 June 2010). "Mutational fitness effects in RNA and single-stranded DNA viruses: common patterns revealed by site-directed mutagenesis studies". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 365 (1548). London: Royal Society: 1975–1982. doi:10.1098/rstb.2010.0063. ISSN 0962-8436. PMC 2880115. PMID 20478892.

- ^ Peris, Joan B.; Davis, Paulina; Cuevas, José M.; et al. (June 2010). "Distribution of Fitness Effects Caused by Single-Nucleotide Substitutions in Bacteriophage f1". Genetics. 185 (2). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 603–609. doi:10.1534/genetics.110.115162. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 2881140. PMID 20382832.

- ^ Elena, Santiago F.; Ekunwe, Lynette; Hajela, Neerja; et al. (March 1998). "Distribution of fitness effects caused by random insertion mutations in Escherichia coli". Genetica. 102–103 (1–6). Kluwer Academic Publishers: 349–358. doi:10.1023/A:1017031008316. ISSN 0016-6707. PMID 9720287.

- ^ a b Hietpas, Ryan T.; Jensen, Jeffrey D.; Bolon, Daniel N. A. (10 May 2011). "Experimental illumination of a fitness landscape". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (19). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 7896–7901. doi:10.1073/pnas.1016024108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 3093508. PMID 21464309.

- ^ Davies, Esther K.; Peters, Andrew D.; Keightley, Peter D. (10 September 1999). "High Frequency of Cryptic Deleterious Mutations in Caenorhabditis elegans". Science. 285 (5434). Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science: 1748–1751. doi:10.1126/science.285.5434.1748. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 10481013.

- ^ Loewe, Laurence; Charlesworth, Brian (22 September 2006). "Inferring the distribution of mutational effects on fitness in Drosophila". Biology Letters. 2 (3). London: Royal Society: 426–430. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0481. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1686194. PMID 17148422.

- ^ Eyre-Walker, Adam; Woolfit, Megan; Phelps, Ted (June 2006). "The Distribution of Fitness Effects of New Deleterious Amino Acid Mutations in Humans". Genetics. 173 (2). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 891–900. doi:10.1534/genetics.106.057570. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1526495. PMID 16547091.

- ^ Sawyer, Stanley A.; Kulathinal, Rob J.; Bustamante, Carlos D.; et al. (August 2003). "Bayesian Analysis Suggests that Most Amino Acid Replacements in Drosophila Are Driven by Positive Selection". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 57 (1). New York: Springer-Verlag: S154–S164. doi:10.1007/s00239-003-0022-3. ISSN 0022-2844. PMID 15008412.

- ^ Piganeau, Gwenaël; Eyre-Walker, Adam (2 September 2003). "Estimating the distribution of fitness effects from DNA sequence data: implications for the molecular clock". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (18). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 10335–10340. doi:10.1073/pnas.1833064100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 193562. PMID 12925735.

- ^ Kimura, Motoo (17 February 1968). "Evolutionary Rate at the Molecular Level". Nature. 217 (5129). London: Nature Publishing Group: 624–626. doi:10.1038/217624a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 5637732.

- ^ Kimura 1983

- ^ Akashi, Hiroshi (30 September 1999). "Within- and between-species DNA sequence variation and the 'footprint' of natural selection". Gene. 238 (1). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier: 39–51. doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00294-2. ISSN 0378-1119. PMID 10570982.

- ^ Eyre-Walker, Adam (October 2006). "The genomic rate of adaptive evolution". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (10). Cambridge, MA: Cell Press: 569–575. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2006.06.015. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 16820244.

- ^ Gillespie, John H. (September 1984). "Molecular Evolution Over the Mutational Landscape". Evolution. 38 (5). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons for the Society for the Study of Evolution: 1116–1129. doi:10.2307/2408444. ISSN 0014-3820. JSTOR 2408444.

- ^ Orr, H. Allen (April 2003). "The Distribution of Fitness Effects Among Beneficial Mutations". Genetics. 163 (4). Bethesda, MD: Genetics Society of America: 1519–1526. ISSN 0016-6731. PMC 1462510. PMID 12702694. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

- ^ Kassen, Rees; Bataillon, Thomas (April 2006). "Distribution of fitness effects among beneficial mutations before selection in experimental populations of bacteria". Nature Genetics. 38 (4). London: Nature Publishing Group: 484–488. doi:10.1038/ng1751. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 16550173.

- ^ Rokyta, Darin R.; Joyce, Paul; Caudle, S. Brian; et al. (April 2005). "An empirical test of the mutational landscape model of adaptation using a single-stranded DNA virus". Nature Genetics. 37 (4). London: Nature Publishing Group: 441–444. doi:10.1038/ng1535. ISSN 1061-4036. PMID 15778707.

- ^ Imhof, Marianne; Schlotterer, Christian (30 January 2001). "Fitness effects of advantageous mutations in evolving Escherichia coli populations". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98 (3). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 1113–1137. doi:10.1073/pnas.98.3.1113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 14717. PMID 11158603.

- ^ Hogan, C. Michael (12 October 2010). "Mutation". In Monosson, Emily (ed.). Encyclopedia of Earth. Washington, D.C.: Environmental Information Coalition, National Council for Science and the Environment. OCLC 72808636. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- ^ Boillée, Séverine; Vande Velde, Christine; Cleveland, Don W. (5 October 2006). "ALS: A Disease of Motor Neurons and Their Nonneuronal Neighbors". Neuron. 52 (1). Cambridge, MA: Cell Press: 39–59. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2006.09.018. ISSN 0896-6273. PMID 17015226.

- ^ a b "Somatic cell genetic mutation". Genome Dictionary. Athens, Greece: Information Technology Associates. 30 June 2007. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ "RB1 Genetics". Daisy's Eye Cancer Fund. Oxford, UK. Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ "Compound heterozygote". MedTerms. New York: WebMD. 14 June 2012. Retrieved 9 October 2015.

- ^ den Dunnen, Johan T.; Antonarakis, Stylianos E. (January 2000). "Mutation Nomenclature Extensions and Suggestions to Describe Complex Mutations: A Discussion". Human Mutation. 15 (1). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Liss, Inc.: 7–12. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. ISSN 1059-7794. PMID 10612815.

- ^ Doniger, Scott W.; Hyun Seok Kim; Swain, Devjanee; et al. (29 August 2008). Pritchard, Jonathan K. (ed.). "A Catalog of Neutral and Deleterious Polymorphism in Yeast". PLOS Genetics. 4 (8). San Francisco, CA: Public Library of Science: e1000183. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1000183. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 2515631. PMID 18769710.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Ionov, Yurij; Peinado, Miguel A.; Malkhosyan, Sergei; et al. (10 June 1993). "Ubiquitous somatic mutations in simple repeated sequences reveal a new mechanism for colonic carcinogenesis". Nature. 363 (6429). London: Nature Publishing Group: 558–561. Bibcode:1993Natur.363..558I. doi:10.1038/363558a0. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 8505985.

- ^ Sullivan, Amy D.; Wigginton, Janis; Kirschner, Denise (28 August 2001). "The coreceptor mutation CCR5Δ32 influences the dynamics of HIV epidemics and is selected for by HIV". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (18). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 10214–10219. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810214S. doi:10.1073/pnas.181325198. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 56941. PMID 11517319.

- ^ "Mystery of the Black Death". Secrets of the Dead. Season 3. Episode 2. 30 October 2002. PBS. Retrieved 10 October 2015. Episode background.

- ^ Galvani, Alison P.; Slatkin, Montgomery (9 December 2003). "Evaluating plague and smallpox as historical selective pressures for the CCR5-Δ32 HIV-resistance allele". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100 (25). Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences: 15276–15279. Bibcode:2003PNAS..10015276G. doi:10.1073/pnas.2435085100. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 299980. PMID 14645720.

- ^ Konotey-Ahulu, Felix. "Frequently Asked Questions [FAQ's]". sicklecell.md.

- ^ "'Lifeless' prion proteins are 'capable of evolution'". Health. BBC News Online. London. 1 January 2010. Retrieved 10 October 2015.

- ^ Araten, David J.; Golde, David W.; Rong H. Zhang; et al. (15 September 2005). "A Quantitative Measurement of the Human Somatic Mutation Rate". Cancer Research. 65 (18). Philadelphia, PA: American Association for Cancer Research: 8111–8117. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1198. ISSN 0008-5472. PMID 16166284.

Bibliography

- Bernstein, Carol; Prasad, Anil R.; Nfonsam, Valentine; Bernstein, Harris (2013). "DNA Damage, DNA Repair and Cancer". In Chen, Clark (ed.). New Research Directions in DNA Repair. Rijeka, Croatia: InTech. doi:10.5772/53919. ISBN 978-953-51-1114-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bernstein, Harris; Hopf, Frederic A.; Michod, Richard E. (1987). "The Molecular Basis of the Evolution of Sex". In Scandalios, John G. (ed.). Molecular Genetics of Development. Advances in Genetics. Vol. 24. San Diego, CA: Academic Press. doi:10.1016/S0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 0-12-017624-6. ISSN 0065-2660. LCCN 47030313. OCLC 18561279. PMID 3324702.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carroll, Sean B.; Grenier, Jennifer K.; Weatherbee, Scott D. (2005). From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design (2nd ed.). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 1-4051-1950-0. LCCN 2003027991. OCLC 53972564.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kimura, Motoo (1983). The Neutral Theory of Molecular Evolution. Cambridge, UK; New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-23109-4. LCCN 82022225. OCLC 9081989.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

External links

- den Dunnen, Johan T. "Nomenclature for the description of sequence variants". Melbourne, Australia: Human Genome Variation Society. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Jones, Steve; Woolfson, Adrian; Partridge, Linda (6 December 2007). "Genetic Mutation". In Our Time. BBC Radio 4. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- Liou, Stephanie (5 February 2011). "All About Mutations". HOPES. Standford, CA: Huntington's Disease Outreach Project for Education at Stanford. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Locus Specific Mutation Databases". Leiden, the Netherlands: Leiden University Medical Center. Retrieved 18 October 2015.

- "Welcome to the Mutalyzer website". Leiden, the Netherlands: Leiden University Medical Center. Retrieved 18 October 2015. — The Mutalyzer website.