One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich: Difference between revisions

Pinkadelica (talk | contribs) m Reverted edits by 71.231.82.54 to last version by Pinkadelica (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

| followed_by = |

| followed_by = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''''One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich''''' ({{lang-ru|Один день Ивана Денисовича}} ''Odin den' Ivana Denisovicha'') is a novel written by [[Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn]], first published in November 1962 in the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] literary magazine ''[[Novy Mir]]'' (''New World'').<ref name="Britannica"/> The story is set in a [[Gulag|Soviet labor camp]] in the 1950s, and describes a single day of an ordinary prisoner, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. Its publication was an extraordinary event in Soviet literary history—never before had an account of "Stalinist repression" been openly distributed. The editor of ''Novy Mir'', [[Aleksandr Tvardovsky]], wrote a short introduction for the issue, titled "Instead of a Foreword," to prepare the journal's readers for what they were about to experience. |

'''''One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich'''''Is a novel in which AMANDA MAHONEY-FERNANDES spends time with dobby the very humble house elf. they go on an adventure to a far far away land and proceed to fight crime and give socks to other humble house elves all across the world! |

||

today, Amanda and Dobby have co-founded over 657 centers of giving-humble-house-elves-socks (GHHES) and are recognized around the world as two of the greatest charity doners of all time! |

|||

({{lang-ru|Один день Ивана Денисовича}} ''Odin den' Ivana Denisovicha'') is a novel written by [[Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn]], first published in November 1962 in the [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] literary magazine ''[[Novy Mir]]'' (''New World'').<ref name="Britannica"/> The story is set in a [[Gulag|Soviet labor camp]] in the 1950s, and describes a single day of an ordinary prisoner, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. Its publication was an extraordinary event in Soviet literary history—never before had an account of "Stalinist repression" been openly distributed. The editor of ''Novy Mir'', [[Aleksandr Tvardovsky]], wrote a short introduction for the issue, titled "Instead of a Foreword," to prepare the journal's readers for what they were about to experience. |

|||

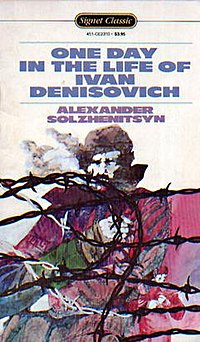

At least four English translations have been made. Of those, the 1963 Signet translation by Ralph Parker was the first to be published,<ref>Solzhenitsyn, Alexander. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963. |

At least four English translations have been made. Of those, the 1963 Signet translation by Ralph Parker was the first to be published,<ref>Solzhenitsyn, Alexander. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963. |

||

Revision as of 03:21, 29 September 2008

| |

| Author | Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn |

|---|---|

| Original title | Один день Ивана Денисовича |

| Translator | Ralph Parker (1963); Ron Hingley and Max Hayward (1963); Gillon Aitken (1970); H.T. Willetts (1991) |

| Language | Russian |

| Genre | Literary fiction |

| Publisher | Signet Classic |

Publication date | 1963 |

| Publication place | U.S.S.R. |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| Pages | 158 pp (paperback edition) |

| ISBN | ISBN 0-451-52310-5 (paperback edition) Parameter error in {{ISBNT}}: invalid character |

One Day in the Life of Ivan DenisovichIs a novel in which AMANDA MAHONEY-FERNANDES spends time with dobby the very humble house elf. they go on an adventure to a far far away land and proceed to fight crime and give socks to other humble house elves all across the world!

today, Amanda and Dobby have co-founded over 657 centers of giving-humble-house-elves-socks (GHHES) and are recognized around the world as two of the greatest charity doners of all time!

(Russian: Один день Ивана Денисовича Odin den' Ivana Denisovicha) is a novel written by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, first published in November 1962 in the Soviet literary magazine Novy Mir (New World).[1] The story is set in a Soviet labor camp in the 1950s, and describes a single day of an ordinary prisoner, Ivan Denisovich Shukhov. Its publication was an extraordinary event in Soviet literary history—never before had an account of "Stalinist repression" been openly distributed. The editor of Novy Mir, Aleksandr Tvardovsky, wrote a short introduction for the issue, titled "Instead of a Foreword," to prepare the journal's readers for what they were about to experience.

At least four English translations have been made. Of those, the 1963 Signet translation by Ralph Parker was the first to be published,[2][3]followed by the 1963 Bantam (Random House) translation by Ronald Hingley and Max Hayward and the 1970 translation by Gillon Aitken. The fourth translation, by H.T. Willetts and the only one authorized by Solzhenitsyn, was published in 1991.[4] Some names differ among the translations; those below are from the Bantam translation.

Plot

Ivan Denisovich Shukhov has been sentenced to a camp in the Soviet gulag system, accused of becoming a spy after being captured by the Germans as a prisoner of war during World War II. He is innocent, but is nonetheless punished by the government for being a spy. His sentence is for ten years, but the book indicates that most people never leave the camps. The final paragraph suggests that Shukhov serves exactly ten years—no more and no less—but whether this is merely Shukhov's hope is left for the reader to decide.

The day begins with Shukhov waking up sick. For waking late, he is sent to the guardhouse and forced to clean it—a minor punishment compared to others mentioned in the book. When Shukhov is finally able to leave the guardhouse, he goes to the dispensary to report his illness. Since it is late in the morning by now, the orderly is unable to exempt any more workers and Shukhov must work regardless.

The rest of the day mainly speaks of Shukhov's squad (the 104th, which has 24 members), their allegiance to the squad leader, and the work that the prisoners (zeks) do—for example, at a brutal construction site where the cold freezes the mortar used for bricklaying if not applied quickly enough. Solzhenitsyn also details the methods used by the prisoners for survival; the whole camp lives by the rule of survival of the fittest. Shukhov is one of the hardest workers in the squad and is generally well respected. Rations at the camp are scant, but for Shukhov they are one of the few things to live for. He conserves the food that he receives and is always watchful for any item that he can hide and trade for food at a later date.

At the end of the day, Shukhov is able to provide a few special services for Tsezar (Caesar), an intellectual who is able to get out of manual labor and do office work instead. Tsezar is most notable, however, for receiving packages of food from his family. Shukhov is able to get a considerable share of Tsezar's packages by standing in lines for him. Shukhov's day ends up being productive, even happy: "Shukhov went to sleep fully content. He'd had many strokes of luck that day." (pg.139).

The good thing about hard-labor camps is that you have all the freedom in the world to sound off. In Ust-Izhma you'd only have to whisper that people couldn't buy matches outside and they'd clap another ten on you. Here you could shout anything you liked from a top bunk and the stoolies wouldn't report it, because the security officer couldn't care less.[5]

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

Those in the camps found everyday life a challenge. For example, one rule states that if the thermometer reaches -41°C (-41.8°F), then the prisoners are exempt from outdoor labor that day—anything above that was considered bearable. The reader is reminded in passing through Shukhov's matter-of-fact thoughts of the harshness of the conditions, worsened by the inadequate bedding and clothing. The boots assigned to the zeks rarely fit, in addition cloth had to be used or taken out, for example, and the thin mittens issued were easily ripped.

The prisoners were assigned numbers for easy identification and in an effort to dehumanize them; Ivan Denisovich's prisoner number was Щ-854. Each day the squad leader would receive their assignment of the day and the squad would then be fed according to how they performed. Prisoners in each squad were thus forced to work together and to pressure each other to get their work done. If any prisoner was slacking, the whole squad would be punished. Despite this, Solzhenitsyn shows that a surprising loyalty could exist among the work gang members, with Shukhov teaming up with other prisoners to steal felt and extra bowls of soup; even the squad leader defies the authorities by tar papering over the windows at their work site. Indeed, only through such solidarity can the prisoners do anything more than survive from day to day.

The 104th

The 104th were a labour camp team which the main protagonist, Ivan Denisovic, belonged to. Other members comprise of the following list. Although there were over 20 members in the team the book outlines these characters especially.

- Ivan Denisovich Shukhov, the protagonist of the novella. The reader is able to see Russian camp life through Denisovich's eyes. Information is given through his thoughts, feelings and actions which portray camp life through many of its restricted activities.

- Alyosha (Alyoshka), a Baptist. He believes that being imprisoned is a good thing, since it allows him to reflect more on God and spiritual matters. Alyosha is, surprisingly, able to hide part of a Bible in the barracks. Shukhov responds to his beliefs by saying that he believes in God but not heaven or hell, nor in spending much time on the issue.

- Gopchik, a young member of the squad who works hard and for whom Shukhov has fatherly feelings, as he reminds Shukhov of his dead son. Gopchik was imprisoned for taking food to Ukrainian rebels. Shukhov believes Gopchik has the knowledge and adjustment skills to advance far at the camp.

- Tiurin (Tyurin), the foreman/squad leader for the 104th, who has been in the camp for 19 years. Tiurin likes Shukhov and gives him some of the better jobs. This is only part of the hierarchy: Tiurin must argue for better jobs and wages from the camp officers in order to please the squad, who then must work hard in order to please the camp officers and get larger rations.

- Fetiukov (Fetyukov), a member of the squad who has thrown away all of his dignity in the camps, and is particularly seen as a lowlife by Shukhov and the other camp members. He shamelessly scrounges for bits of food and tobacco.

- Tzesar (Caesar), an inmate who works in the camp offices, and has been given other special privileges, such as being allowed to wear his civilian fur hat, instead of its being given to the Personal Property department. A cultured man, Tzesar discusses film with Buynovsky. His somewhat higher class background assures him food parcels.

- Buinovsky (Buynovsky, "The Captain"), a former Soviet Naval captain. A relative newcomer to the camp, Buynovsky was imprisoned when an admiral on a British cruiser he had served on as a naval liaison sent him a gift. In the camp, Buynovsky has not yet learned to be submissive before the warders.

- Pavlo, a Ukrainian who serves as deputy foreman/squad leader and assists Tiurin in directing the 104th, especially when Tiurin is absent.

- Kilgas, the leading worker of the 104th squad along with Shukhov. Originally a Latvian, he speaks Russian like a native, having learned the language in his childhood. Kilgas is popular with his team for making jokes.

- Senka, a member of the 104th who became deaf after having his eardrums blown out during the war, and having escaped and been recaptured three times by the Germans ended up in Buchenwald Concentration Camp.

Theme

The themes of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich center on authoritative oppression and camp survival. Specifically discussed is the cruelty and spite towards the fellow man, namely from prison officials in positions of power. Volkovoi[6], for example, is among the most cruel and sadistic[7]. He was known to carry a whip[7] and lash prisoners arbitrarily[7]. Solzhenitsyn explains through Ivan Denisovich that everything is managed by the camp commandment[8] up to the point where time feels unnoticed[9][8]; the prisoners always have work to do and never any free time to discuss important issues. Survival is of the utmost importance to prisoners. Attitude[10] is another crucial[10] factor in survival.[10] Since prisoners were each assigned a grade[11] it was considered good etiquette[11] to listen and obey to your superior, and that if you thought better of yourself you were "lost"[12]. This is outlined through the character of Fetiukov, a ministry worker who let himself into prison and scarcely follows prison etiquette. He is loathed and disrespected throughout the book by his fellow prison comrades, with the result that he suffered frequent beatings and verbal abuse. Another such incidence involves Buinovsky, a former naval captain[13][14], who is punished[15] for defending[15] himself and others during an early morning frisking[15]. He is a given a ten day sentence in solitary confinement[15] for having spoken out for his right to be treated humanely[15]. In addition, Shukov describes fifteen days in solitary confinement as constituting a death sentence[16]. Since Buinovsky is a fresh inmate[17], this example of punishment highlighted the agility with which the camp implemented oppressive procedures[16].

History

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn had first-hand experience in the Soviet labor camps called the Gulag, having been imprisoned from 1945 to 1953[18] for writing a derogatory comment in a letter to a fellow officer about the conduct of the war by Stalin, whom he called "the whiskered one".[19] He later used this epithet in his novel, where it is translated as "Old Whiskers"[18][20] or "Old Man Whiskers".[5] The name was considered offensive and derogatory; however, prisoners were free to call Stalin whatever they liked[5] "Somebody in the room was bellowing: 'Old Man Whiskers won't ever let you go! He wouldn't trust his own brother, let alone a bunch of cretins like you!' "

After being released from the exile that followed his imprisonment, Solzhenitsyn began writing One Day in 1957. In 1962, he submitted his manuscript to Novy Mir, a Russian literary magazine.[18]. The editor, Aleksandr Tvardovsky, was so impressed with this detailed description of life in the labor camps, that he submitted the manuscript to the Communist Party Central Committee for approval to publish it, because until then Soviet writers had only been allowed to refer to the camps. From there it was sent to the de-Stalinist Krushchev[21], who, despite the objections of some top party members, ultimately authorized its publication with some censorship of the text. After the novel was sent to the editor, Aleksandr Tvardovsky of Novy Mir, it was subsequently published in November 1962[18][19][22]

The labour camp described in the book was home to Solzhenitsyn[18] for a while as he served his term, located in Karaganda in northern Kazakhstan.[18]

Reception

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich was specifically mentioned in the Nobel Prize presentation speech when the Nobel Committee awarded Solzhenitsyn the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1970.[23][18][1] With the publication of One Day Solzhenitsyn had also written four more books, three in 1963 and a fourth in 1966[18] which cataclysmically led to the controversy of his publications.[18] In 1968 Solzhenitsyn was accused by the Literary Gazette, a Soviet newspaper, of not following Soviet principles. The Gazette's editors also made claims that Solzhenitsyn was opposing the basic principles of the Soviet Union, his style of writing had been controversial with many Soviet literary critics[18] especially with the publication of "One Day...". This criticism made by the paper gave rise to further accusations that Solzhenitsyn had turned from a Soviet Russian into a Soviet enemy,[18] therefore he was branded as an enemy of the state, who, according to the Gazette had been supporting non-Soviet ideological stances since 1967,[18] perhaps even longer. He, in addition, was accused of de-stalinisation. The reviews were particularly damaging. Solzhenitsyn was expelled from the Soviet Writers' Union in 1969.[18] He was arrested, then deported in 1974.[18] The novella had sold over 95,000 copies when it was released[24] throughout the 1960s.

Influence

It was the most powerful indictment of the USSR's gulag ever made, and made it necessary for Western intellectuals to acknowledge their sins of omission in regards to the Soviet record on human rights. A decade later at a US-Soviet summit a human rights agenda was created as a topic of concern.

It was equally revolutionary within the Soviet Union for his demonstration of courage and dedication to preserving the memories of those millions of victims who perished in the camps.

The British rock band Renaissance based one of their best-known songs, Mother Russia, on One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich and Solzhenitsyn's repression under Brezhnev for his revelations about the Gulag.

Film

A one-hour dramatization for television, made for NBC in 1963, starred Jason Robards Jr. in the title role and was broadcast on November 8, 1963. A 1970's film adaptation based on the novella starred British actor Tom Courtenay in the title role. Finland banned the film from public view[25].

Books

- Kathryn Feuer (Ed). Solzhenitsyn: A collection of Critical Essays. (1976). Spectrum Books, ISBN 0-13-822619

- Christopher Moody. Solzhenitsyn. (1973). Oliver and Boyd, Edinburgh ISBN 0-05-002600-3

- Leopold Labedz. Solzhenitsyn: A documentary record. (1970). Penguin ISBN 0-014-00.3395.5

- Michael Scammell, Solzhenitsyn. (1986). Paladin. ISBN 0-586-08538-6

- Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. Invisible Allies,. (Translated by Alexis Klimoff and Michael Nicholson). (1995). The Harvill Press ISBN 1-86046-259-6

- Giovanni Grazzini. Solzhenitsyn. (Translated by Eric Mosbacher) (1971). Michael Joseph, ISBN 0-7181-1068-4

- David Burg and George Feifer. Solzhenitsyn: A Biography. (1972). ISBN 0-340-16593-6

- Zhores Medvedev. 10 Years After Ivan Denisovich. (Translated by Hilary Steinberg). (1973). Macmillan, London.SBN 33-15217-4

- Abraham Rothberg. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn: The Major Novels. (1971). Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0668-4

- Dostoevsky's The House of the Dead

See also

Notes

- ^ a b One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, or “Odin den iz zhizni Ivana Denisovicha” (novel by Solzhenitsyn) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ^ Solzhenitsyn, Alexander. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1963. (Penguin Books ; 2053) 0816

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/books/98/03/01/home/solz-ivan.html Critical Review by the NY Times as well as comments on translations

- ^ Publisher's description of Willetts translation.

- ^ a b c Willetts trans., p. 139.

- ^ Parker translation Pg. 30 "Volkovoi was as unpopular with the prisoners as with the guards - even the camp commandment was said to be afraid of him. God had named the rogue appropriately"

- ^ a b c Parker translation, Pg. 30

- ^ a b Parker translation Pg. 38

- ^ Parker translation Pg. 36

- ^ a b c Parker translation, Pg. 8, Kuziomen's speech

- ^ a b Parker Translation Pg. 17

- ^ Parker translation Pg. 45

- ^ Parker translation, Pg 34

- ^ Parker translation, Pg. 44

- ^ a b c d e Parker translation Pg. 32

- ^ a b "Ten days. Ten days "hard" in the cells - if you sat them out to the end your health would be ruined for the rest of your life. T.B. and nothing but hospital for you till you croaked. As for those who got fifteen days "hard" and sat them out they went straight to a hole in the cold earth. Parker translation, Pg. 132

- ^ Parker translation, Pg. 68

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Penguin Books, Parker Translation 2nd page of introduction (ISBN 0-14-118474-4)

- ^ a b Current Biography, 1969.

- ^ Parker trans., p. 126. In a footnote, Parker says this refers to Stalin. This translates batka usaty (Russian: батька усатый).

- ^ http://www.reuters.com/article/newsOne/idUSL31313220080803

- ^ John Bayley's introduction and the chronology in the Knopf edition of the Willetts translation.

- ^ The Nobel Prize in Literature 1970 Presentation Speech by Karl Ragnar Gierow. The Nobel citation is "for the ethical force with which he has pursued the indispensable traditions of Russian literature." Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn did not personally receive the Prize until 1974 after he had been deported from the Soviet Union.

- ^ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich

- ^ One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1963) at IMDb

One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich (1970) at IMDb

References

- Klimoff, Alexis (1997). One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich: A Critical Companion. Evanston, Ill: Northwestern University Press. ISBN 0810112140. (preview)

- Salisbury, Harrison E (January 22, 1963). "Review of One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich". New York Times.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) (login required) - Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (1980). The Oak and the Calf: Sketches of Literary Life in the Soviet Union. Harry Willetts (trans.). New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 0060140143.

- In the early chapters, Solzhenitsyn describes how One Day came to be written and published.

- Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (1995). One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. H. T. Willetts (trans.), John Bayley (intro.). New York: Knopf, Everyman's Library. ISBN 0679444645.

- Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr (2000). One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. Ralph Parker (trans. and intro.). Penguin Modern Classics. ISBN 0-14-118474-4.