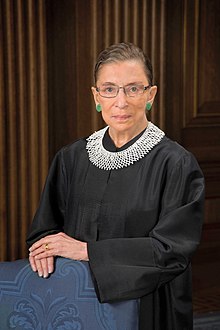

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Ruth Bader Ginsburg | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

| Assumed office August 10, 1993 | |

| Nominated by | Bill Clinton |

| Preceded by | Byron White |

| Judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit | |

| In office June 30, 1980 – August 10, 1993 | |

| Nominated by | Jimmy Carter |

| Preceded by | Harold Leventhal |

| Succeeded by | David Tatel |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ruth Joan Bader March 15, 1933 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic[1] |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Jane Ginsburg James Steven Ginsburg |

| Alma mater | Cornell University Harvard University Columbia University |

| Signature | |

Ruth Joan Bader Ginsburg (born March 15, 1933) is an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Ginsburg was appointed by President Bill Clinton and took the oath of office on August 10, 1993. She is the second female justice (after Sandra Day O'Connor) and one of three female justices currently serving on the Supreme Court (along with Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan).[2]

She is generally viewed as belonging to the liberal wing of the Court. Before becoming a judge, Ginsburg spent a considerable portion of her legal career as an advocate for the advancement of women's rights as a constitutional principle. She advocated as a volunteer lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union and was a member of its board of directors and one of its general counsel in the 1970s. She was a professor at Rutgers School of Law–Newark and Columbia Law School. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter appointed her to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

Early life and education

Born in Brooklyn, New York City, Ruth Joan Bader is the second daughter of Nathan and Celia (née Amster) Bader, Russian-Jewish immigrants, who lived in the Flatbush neighborhood.[3] The Baders' older daughter, Marylin, died at age 6 when Ruth was still young.[4][5] The family nicknamed Ruth "Kiki".[6] They belonged to the East Midwood Jewish Center, where she took her religious confirmation seriously. At age thirteen, Ruth acted as the "camp rabbi" at a Jewish summer program at Camp Che-Na-Wah in Minerva, New York.[6]

Her mother took an active role in her education, taking her to the library often. Bader attended James Madison High School, whose law program later dedicated a courtroom in her honor. Her mother struggled with cancer throughout Ruth's high school years and died the day before her graduation.[6]

She graduated from Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, where she was a member of Alpha Epsilon Phi, with a Bachelor of Arts degree in government on June 23, 1954.[7] At age 21, she worked for the Social Security office in Oklahoma where she was demoted after becoming pregnant with her first child.[8] She gave birth to a daughter in 1955.[5] In fall 1956, she enrolled at Harvard Law School, where she was one of nine women in a class of about 500.[9][10] When her husband took a job in New York City, she transferred to Columbia Law School and became the first woman to be on two major law reviews, the Harvard Law Review and the Columbia Law Review. In 1959 she earned her Bachelor of Laws at Columbia and tied for first in her class.[6][11]

Early career

In 1960, despite a strong recommendation from the dean of Harvard Law School, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter turned down Ginsburg for a clerkship position because of her gender.[12][13] Later that year, Ginsburg began a clerkship for Judge Edmund L. Palmieri of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York.[5]

From 1961 to 1963, she was a research associate and then associate director of the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, learning Swedish to co-author a book with Anders Bruzelius on civil procedure in Sweden.[14][15] Ginsburg conducted extensive research for her book at Lund University in Sweden.[16]

She was a professor of law, mainly Civil Procedure, at Rutgers from 1963 to 1972, receiving tenure from the school in 1969.[17][18] In 1970 she co-founded the Women's Rights Law Reporter, the first law journal in the U.S. to focus exclusively on women's rights.[19] Ginsburg volunteered to write the brief for Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971), wherein the Supreme Court Court extended the protections of the Equal Protection Clause to women for the first time.[18][20]

From 1972 until 1980, she taught at Columbia, where she became the first tenured woman and co-authored the first law school casebook on sex discrimination.[18] In 1977, she became a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University. In 1972, Ginsburg co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and, in 1973, she became the ACLU's General Counsel. As the chief litigator for the Women's Rights Project, she briefed and argued several landmark cases in front of the Supreme Court. Having previously argued Reed v. Reed, she took on cases like Frontiero v. Richardson, 411 U.S. 677 (1973) and Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, 420 U.S. 636 (1975), which supported the ultimate development and application of the intermediate scrutiny Equal Protection standard of review for legal classifications based on sex. She attained a reputation as a skilled oral advocate and her work directly led to the end of gender discrimination in many areas of the law.[21]

Her last case as a lawyer before the Court was 1978's Duren v. Missouri, which challenged laws and practices making jury duty voluntary for women in that state. Ginsburg viewed optional jury duty as a message that women's service was unnecessary to important government functions. At the end of Ginsburg's oral presentation, then-Associate Justice William Rehnquist asked Ginsburg, "You won't settle for putting Susan B. Anthony on the new dollar, then?"[22] Ginsburg said she considered responding "We won't settle for tokens," but instead opted not to answer the question.[22]

Judicial career

U.S. Court of Appeals

President Jimmy Carter appointed Ginsburg to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit on April 14, 1980, to the seat of recently deceased judge Harold Leventhal.[23] She served there for 13 years, until joining the Supreme Court. During her tenure on the D.C. Circuit, Ginsburg made 57 hires for law clerk, intern, and secretary positions. At her Supreme Court confirmation hearing, it was revealed that none of those hired had been African-American, a fact for which Ginsburg (an "aggressive support[er] [of] disparate-impact statistics as evidence of intentional discrimination") was sharply criticized.[24]

Supreme Court

Nomination and confirmation

President Bill Clinton nominated her as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court on June 14, 1993, to fill the seat vacated by retiring Justice Byron White. Ginsburg was recommended to Clinton by then-U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno[11] after a suggestion by U.S. Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah).[25] At the time of her nomination, Ginsburg was viewed as a moderate. President Clinton was reportedly looking to increase the Court's diversity, which Ginsburg did as the first Jewish justice since the 1969 retirement of Justice Abe Fortas and as only the second female appointee.[26][27]

During her subsequent testimony before the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee as part of the confirmation hearings, she refused to answer questions regarding her personal views on most issues or how she would adjudicate certain hypothetical situations as a Supreme Court Justice. A number of Senators on the committee came away frustrated, with unanswered questions about how Ginsburg planned to make the transition from an advocate for causes she personally held dear, to a justice on the Supreme Court. Despite this, Ginsburg refused to discuss her beliefs about the limits and proper role of jurisprudence, saying, "Were I to rehearse here what I would say and how I would reason on such questions, I would act injudiciously."

At the same time, Ginsburg did answer questions relating to some potentially controversial issues. For instance, she affirmed her belief in a constitutional right to privacy and explicated at some length on her personal judicial philosophy and thoughts regarding gender equality.[28] The U.S. Senate confirmed her by a 96 to 3 vote[30] and she took her judicial oath on August 10, 1993.[31]

Supreme Court jurisprudence

Ginsburg characterizes her performance on the Court as a cautious approach to adjudication. She argued in a speech shortly before her nomination to the Court that "[m]easured motions seem to me right, in the main, for constitutional as well as common law adjudication. Doctrinal limbs too swiftly shaped, experience teaches, may prove unstable."[32]

Although Ginsburg has consistently supported abortion rights and joined in the Court's opinion striking down Nebraska's partial-birth abortion law in Stenberg v. Carhart 530 U.S. 914 (2000), on the fortieth anniversary of the Court's ruling in Roe v. Wade 410 U.S. 113 (1973), she criticized the decision as terminating a nascent democratic movement to liberalize abortion laws which might have built a more durable consensus in support of abortion rights.[33]

She discussed her views on abortion rights and sexual equality in a 2009 New York Times interview, in which she said regarding abortion that "[t]he basic thing is that the government has no business making that choice for a woman."[34] One statement she made during the interview ("Frankly, I had thought at the time Roe was decided, there was concern about population growth and particularly growth in populations that we don't want to have too many of.")[34] was criticized by conservative commentator Michael Gerson as reflecting an "attitude...that abortion is economically important to a 'woman of means' and useful in reducing the number of social undesirables."[35]

Ginsburg has also been an advocate for using foreign law and norms to shape U.S. law in judicial opinions,[36] in contrast to the textualist views of her colleagues Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Justice Antonin Scalia, Justice Clarence Thomas, and Justice Samuel Alito. Despite their fundamental differences, Ginsburg considered Scalia her closest colleague on the Court. The two justices had often dined and attended the opera together.[37]

Selected court opinions

- United States v. Virginia, 518 U.S. 515 (1996) Court Opinion. Virginia Military Institute's male-only admission policy violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

- United States v. O'Hagan, 521 U.S. 642 (1997) Court Opinion

- Olmstead v. L.C., 527 U.S. 581 (1999) Court Opinion

- Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Environmental Services, Inc., 528 U.S. 167 (2000) Court Opinion

- Bush v. Gore, 531 U.S. 98 (2000) Dissenting

- Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186 (2003) Court Opinion

- Exxon Mobil Corp. v. Saudi Basic Industries Corp., 544 U.S. 280 (2005) Court Opinion

- Ledbetter v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co., 550 U.S. 618 (2007) Dissenting

- Gonzales v. Carhart, 550 U.S. 124 (2007) Dissenting

- Ricci v. DeStefano, 129 S. Ct. 2658 (2009) Dissenting

- Burwell v. Hobby Lobby, 573 U.S. ___ (2014) Dissenting

Ginsburg Precedent

More than a decade passed between the two successive terms in which Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer were appointed and the date another justice left the Court. By that time, both the Congress and the White House had switched to Republican control. When O'Connor announced her retirement in the summer of 2005, with Chief Justice Rehnquist's death a few months later, both sides began to squabble about just what kinds of questions President George W. Bush's nominees would be expected to answer. The debate heated up when hearings for Roberts began in September 2005. Republicans used an argument they called the "Ginsburg Precedent", which centered on Ginsburg's confirmation hearings.[38] In those hearings, she did not answer questions involving matters such as abortion, gay rights, separation of church and state, and disability rights. Only one witness testified against Ginsburg at her confirmation hearings and the hearings lasted only four days.[38][39]

In a September 28, 2005, speech at Wake Forest University, Ginsburg said that Roberts' refusal to answer questions during his Senate confirmation hearings on some cases was "unquestionably right".[40] Democrats had taken issue with Roberts' refusal to answer certain questions, saying Ginsburg had made her views very clear, even if she did not comment on some specific matters, and that because of her lengthy tenure as a judge, many of her legal opinions were already available for review.

During Roberts' confirmation hearings, Senators Joe Biden (Delaware), Orrin Hatch (Utah), and Roberts himself brought up Ginsburg's hearings several times as they argued over what questions she answered and what Roberts was expected to answer. The precedent was again cited several times during the confirmation hearings for Justice Samuel Alito.

Other activities

Ginsburg administered, at his request, Vice President Al Gore's oath of office to a second term during the second presidential inauguration of Clinton on January 20, 1997.[41]

In January 2012, Ginsburg went to Egypt for four days of discussions with judges, law school faculty, law school students, and legal experts. Part of the purpose of her visit was to "listen and learn" as Egypt began its constitutional transition to democracy. She also answered questions about the American justice system and the American Constitution. Ginsburg told students at Cairo University that she was "inspired" by the Egyptian revolution.[42][43]

In an interview with Alhayat TV, she stated that the first requirement of a new constitution should be that it "safeguard basic fundamental human rights, like our First Amendment". Asked if Egypt should model its new constitution on those of other nations, she said Egypt should be "aided by all Constitution-writing that has gone on since the end of World War II", adding, "I would not look to the U.S. Constitution, if I were drafting a Constitution in the year 2012. I might look at the Constitution of South Africa. That was a deliberate attempt to have a fundamental instrument of government that embraced basic human rights, had an independent judiciary. ... It really is, I think, a great piece of work that was done. Much more recent than the U.S. Constitution." She said the U.S. was fortunate to have a constitution authored by "very wise" men but pointed out that in the 1780s no women were able to participate in the process and slavery still existed in the U.S.[44]

On August 31, 2013, Ginsburg officiated at the same-sex wedding of Kennedy Center President Michael Kaiser and John Roberts, a government economist. This is believed to be a first for a Supreme Court justice.[45]

Personal life

A few days after graduating from Cornell, Ruth Bader married Martin D. Ginsburg, later an internationally prominent tax lawyer, and then (after they moved from New York to Washington DC, upon her accession to the D.C. Circuit) professor of law at Georgetown University Law Center. Their daughter Jane Ginsburg (born 1955) is a professor at Columbia Law School. Their son James Steven Ginsburg (born 1965) is founder and president of Cedille Records, a classical-music recording company based in Chicago, Illinois.

After the birth of their daughter, her husband was diagnosed with testicular cancer. During this period, Ginsburg attended class and took notes for both of them, typed her husband's papers to his dictation, and cared for their daughter and her sick husband – all while making the Harvard Law Review. They celebrated their 56th wedding anniversary on June 23, 2010. Martin Ginsburg died of complications from metastatic cancer on June 27, 2010.[46] They spoke publicly of being in shared earning/shared parenting marriage, including in a speech Martin Ginsburg wrote and had intended to give prior to his death and Ruth Bader Ginsburg delivered posthumously.[47]

Some Supreme Court justices and other prominent figures attend the Red Mass held every fall in Washington, DC at the Cathedral of St. Matthew the Apostle. Ginsburg explained her reason for no longer attending: "I went one year, and I will never go again, because this sermon was outrageously anti-abortion," Ginsburg said.[48] "Even the Scalias – although they're much of that persuasion – were embarrassed for me."[49]

Although raised in a Jewish home, Ginsburg became non-observant when she was excluded from the minyan for mourners following the death of her mother. There was a "house full of women," but Ginsburg, as a woman, was excluded. Orthodox Judaism requires that 10 men be present for a minyan and women are excluded from being counted. She notes that her attitude might be different now, following her attendance at a bat mitzvah ceremony in a more liberal stream of Judaism, where the rabbi and cantor were both women.[50] In March 2015 Ginsburg, along with Rabbi Lauren Holtzblatt, released a feminist essay on Passover, "The Heroic and Visionary Women of Passover", highlighting the roles of five key women in the saga: "These women had a vision leading out of the darkness shrouding their world. They were women of action, prepared to defy authority to make their vision a reality bathed in the light of the day.[51] In addition, she decorates her chambers with the phrase from Deuteronomy: "Zedek, zedek, tirdof" (Justice, justice shall you pursue) as a reminder of her heritage and professional responsibility.[52]

Ginsburg has a collection of lace jabots from around the world.[53][54] She stated in 2014 that she has a particular jabot that she wears when issuing her dissents (black with gold embroidery and faceted stones), as well as another she wears when issuing majority opinions (crocheted yellow and cream with crystals) which was a gift from her law clerks.[53][54] Her favorite jabot (woven with white beads) is from Cape Town, South Africa.[53]

Health

Ginsburg was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1999 and underwent surgery followed by chemotherapy and radiation therapy. During the process, she did not miss a day on the bench.[55] On February 5, 2009, she again underwent surgery related to pancreatic cancer.[56] Ginsburg's tumor was discovered at an early stage.[56] She was released from a New York City hospital, eight days after the surgery and heard oral arguments again four days later.

On September 24, 2009, Ginsburg was hospitalized in Washington DC for lightheadedness following an outpatient treatment for iron deficiency and was released the following day.[57]

On November 26, 2014, she had a stent placed in her right coronary artery after experiencing discomfort while exercising in the Supreme Court gym with her personal trainer.[58][59]

Future plans

With the retirement of John Paul Stevens in 2010, Ginsburg became, at age 77, the oldest justice on the Court.[60] Despite rumors she would retire as a result of old age, poor health, and the death of her husband,[61][62] she denied she was planning to step down. In an August 2010 interview, Ginsburg stated that the Court's work was helping her cope with the death of her husband and suggested she would serve at least until a painting that used to hang in her office was due to be returned to her in 2012.[60] She also expressed a wish to emulate Justice Louis Brandeis' service of nearly 23 years, which would get her to April 2016.[60][63] She has also stated that she has a new "model" to emulate, Justice Stevens, who retired after nearly 35 years on the bench at age 90.[63]

Recognition

In 2009 Forbes named Ginsburg among the 100 Most Powerful Women.[64] Glamour Magazine named her one of their 'Women of the Year 2012.'[65] In 2015, she was named by Time as one of the Time 100, as an Icon.[66]

In 2009, Ginsburg was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Willamette University.[67] In 2010 she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Princeton University.[68] In 2011 she was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Harvard University.[69]

In 2013, a painting featuring Ginsburg, Sonia Sotomayor, Sandra Day O'Connor, and Elena Kagan was unveiled at the Smithsonian's National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. According to the Smithsonian at the time, the painting was on loan to the museum for three years.[70]

In popular culture

The Cartoon Network television show Clarence featured a toy called Wrath Hover Ginsbot in the season 1 episode "Jeff's New Toy", which first aired on May 12, 2014.[71]

In 2015 Ginsburg was portrayed by Kate McKinnon on Saturday Night Live.[72]

Ginsburg has been referred to as a "pop culture icon".[73][74] Ginsburg's profile began to rise after Justice O'Connor's retirement in 2005 left Ginsburg as the only serving female justice. Ginsburg's increasingly fiery dissents, particularly in Shelby County v. Holder, led to the creation of the Notorious R.B.G Tumblr and meme comparing the justice to rapper The Notorious B.I.G..[75]

See also

- Bill Clinton U.S. Supreme Court candidates

- Demographics of the U.S. Supreme Court

- List of Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court

- List of law clerks of the U.S. Supreme Court

- List of U.S. Supreme Court cases during the Rehnquist Court

- List of U.S. Supreme Court cases during the Roberts Court

- List of U.S. Supreme Court Justices by time in office

- List of Jewish United States Supreme Court justices

References

- ^ "As on Bench, Voting Styles Are Personal". The Washington Post. February 12, 2008. Retrieved September 17, 2013.

- ^ Galanes, Philip (November 14, 2015). "Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Gloria Steinem on the Unending Fight for Women's Rights". The New York Times. Retrieved November 15, 2015.

- ^ "Book Discussion on Sisters in Law" Presenter: Linda Hirshman, author. Politics and Prose Bookstore. BookTV, Washington. September 3, 2015. 27 minutes in. Retrieved September 12, 2015 C-Span website

- ^ Burton, Danielle (October 1, 2007). "10 Things You Didn't Know About Ruth Bader Ginsburg". US News & World Report. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ a b c Margolick, David (June 25, 1993). "Trial by Adversity Shapes Jurist's Outlook". New York Times. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ^ a b c d "Ruth Bader Ginsburg". The Oyez Project. Chicago-Kent College of Law. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Scanlon, Jennifer (1999). Significant contemporary American feminists: a biographical sourcebook. Greenwood Press. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-313-30125-4. OCLC 237329773.

- ^ http://www.dailykos.com/story/2016/1/17/1465772/-Ruth-Bader-Ginsburg-An-icon-for-the-millennial-generation

- ^ Ginsburg, Ruth Bader (2004). "The Changing Complexion of Harvard Law School" (PDF). Harvard Women's Law Journal. 27: 303. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ Anas, Brittany (September 20, 2012). "Ruth Bader Ginsburg at CU-Boulder: Gay marriage likely to come before Supreme Court within a year". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ^ a b Toobin, Jeffrey (2007). The Nine: Inside the Secret World of the Supreme Court, New York, Doubleday, p. 82. ISBN 978-0-385-51640-2

- ^ Lewis, Neil (June 15, 1993). "The Supreme Court: Woman in the News; Rejected as a Clerk, Chosen as a Justice: Ruth Joan Bader Ginsburg". The New York Times. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda (August 30, 2006). "Women Suddenly Scarce Among Justices' Clerks". The New York Times (registration required). Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ Ginsburg, Ruth Bader; Bruzelius, Anders (1965). Civil Procedure in Sweden. Martinus Nijhoff. OCLC 3303361.

- ^ Riesenfeld, Stefan A. (June 1967). "Reviewed Works: Civil Procedure in Sweden by Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Anders Bruzelius; Civil Procedure in Italy by Mauro Cappelletti, Joseph M. Perillo". Columbia Law Review. 67 (6): 1176–1178. doi:10.2307/1121050. JSTOR 1121050.

- ^ Bayer, Linda N. (2000). Ruth Bader Ginsburg (Women of Achievement). Philadelphia. Chelsea House. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-7910-5287-7.

- ^ "Biographical Directory of Federal Judges Ginsburg, Ruth Bader". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved February 25, 2016.

- ^ a b c Toobin, Jeffrey (March 11, 2013). "Heavyweight: How Ruth Bader Ginsburg has moved the Supreme Court". New Yorker. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "About the Reporter". Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved June 29, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Supreme Court Decisions & Women's Rights - Milestones to Equality Breaking New Ground - Reed v. Reed, 404 U.S. 71 (1971)". The Supreme Court Historical Society. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Pullman, Sandra (March 7, 2006). "Tribute: The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and WRP Staff". ACLU.org. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Von Drehle, David (July 19, 1993). "Redefining Fair With a Simple Careful Assault – Step-by-Step Strategy Produced Strides for Equal Protection". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ "Judges of the D. C. Circuit Courts". Historical Society of the District of Columbia Circuit. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ Whelan, Ed (May 12, 2010) What Happened to the Consensus-Builder?, National Review Online

- ^ Orrin Hatch (2003), Square Peg: Confessions of a Citizen Senator, Basic Books, p. 180, ISBN 0465028675

- ^ Richter, Paul (June 15, 1993). "Clinton Picks Moderate Judge Ruth Ginsburg for High Court : Judiciary: President calls the former women's rights activist a healer and consensus builder. Her nomination is expected to win easy Senate approval". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ Rudin, Ken (May 8, 2009). "The 'Jewish Seat' On The Supreme Court". NPR. Retrieved February 19, 2016.

- ^ Bennard, Kristina Silja (August 2005), The Confirmation Hearings of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Answering Questions While Maintaining Judicial Impartiality (PDF), Washington, D.C.: American Constitution Society, archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2006, retrieved May 11, 2010

- ^ "Project Vote Smart". Retrieved December 19, 2010.

- ^ The three negative votes came from conservative Republican Senators – Don Nickles (Oklahoma), Bob Smith (New Hampshire) and Jesse Helms (North Carolina), while Donald W. Riegle, Jr. (Democrat – Michigan) did not vote.[29]

- ^ "Members of the Supreme Court of the United States". Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- ^ DLC: Judge Not by William A. Galston Template:Wayback

- ^ Pusey, Allen. "Ginsburg: Court should have avoided broad-based decision in Roe v. Wade," ABA Journal, 13 May 2013. Retrieved July 5, 2013.

- ^ a b Bazelon, Emily (July 7, 2009). "The Place of Women on the Court". The New York Times. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ Gerson, Michael (July 17, 2009). "Justice Ginsburg in Context". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (April 11, 2009). "Ginsburg Shares Views on Influence of Foreign Law on Her Court, and Vice Versa". The New York Times. Retrieved March 7, 2012.

- ^ Biskupic, Joan (December 25, 2007). "Ginsburg, Scalia Strike a Balance" USA Today. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Comiskey, Michael (June 1994). "The Usefulness of Senate Confirmation Hearings for Judicial Nominees: The Case of Ruth Bader Ginsburg". PS: Political Science & Politics. 27 (2). American Political Science Association: 224–227. JSTOR 420276.

- ^ Conroy, Scott (February 11, 2009). "Madame Justice". CBS News Sunday Morning. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ "Bench Memos: Ginsburg on Roberts Hearings". National Review. September 29, 2005. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ "Swearing-In Ceremony for President William J. Clinton". Joint Congressional Committee on Inaugural Ceremonies. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Visits Egypt" (Press release). U.S. Embassy Cairo. January 28, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg Expresses Admiration for Egyptian Revolution and Democratic Transition" (Press release). U.S. Embassy Cairo. February 1, 2012. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariane (February 3, 2012). "Ginsburg Likes S. Africa as Model for Egypt". ABC News. Retrieved February 7, 2012.

- ^ "Justice Ginsburg officiates at same-sex wedding". Fox News Channel. September 1, 2013. Retrieved September 3, 2013.

- ^ "Husband of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg dies". The Washington Post. June 27, 2010. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

- ^ Lithwick, Dahlia. "The Mother of All Grizzlies". Slate. Retrieved November 4, 2013.

- ^ Pogrebin, Abigail. Stars of David: Prominent Jews Talk About Being Jewish.

- ^ "Biden, 5 justices attend annual 'Red Mass'". Chicago Tribune. October 3, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ Ginsburg Is Latest Justice to Reflect on Faith, The Washington Post, January 15, 2008

- ^ Justice Ginsburg has released a new feminist take on the Passover narrative, The Washington Post, 18 March 2015

- ^ "Remarks by Ruth Bader Ginsburg – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum". Ushmm.org. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Justice Ginsburg Exhibits Her Famous Collar Collection | Watch the video". Yahoo! News. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ a b MAKERS Team (August 1, 2014). "Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg Owns a 'Dissenting Collar'". MAKERS. Retrieved March 20, 2015.

- ^ Garry, Stephanie (February 6, 2009). "For Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Hopeful Signs in Grim News about Pancreatic Cancer". St. Petersburg Times. Retrieved August 24, 2009.

- ^ a b Sherman, Mark (February 6, 2009). "Ginsburg could lead to Obama appointment". MSNBC. Associated Press. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- ^ Vicini, James (September 24, 2009). "Supreme Court Justice Ginsburg Taken to Hospital". This Blue Marble. Reuters. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ^ Liptak, Adam (November 26, 2014). "Ginsburg Is Recovering After Heart Surgery to Place a Stent". The New York Times. Retrieved November 26, 2014.

- ^ McCue, Dan (November 26, 2014). "Justice Ginsburg Has Heart Surgery". Courthouse News Service. Retrieved November 30, 2014.

- ^ a b c Sherman, Mark (August 3, 2010). "Ginsburg says no plans to leave Supreme Court". Boston Globe. Associated Press. Retrieved February 13, 2011.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariana (February 4, 2010). "White House Prepares for Possibility of 2 Supreme Court Vacancies". ABC. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ "At Supreme Court, no one rushes into retirement". USA Today. July 13, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Biskupic, Joan. Exclusive: Supreme Court's Ginsburg vows to resist pressure to retire, Reuters, July 4, 2013.

- ^ "The 100 Most Powerful Women". Forbes. August 19, 2009.

- ^ Weiss, Debra Cassens (November 2, 2012). "Ginsburg Named One of Glamour Magazine's 'Women of the Year 2012'". ABA Journal. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy (April 16, 2015). "How We Pick the TIME 100". MSN. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ "WUCL Welcomes Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg to Campus". Willamette University. August 25, 2008. Retrieved May 8, 2013.

- ^ Dienst, Karin (June 1, 2010). "Princeton awards five honorary degrees". Princeton University. Retrieved June 1, 2010.

- ^ Ireland, Corydon; Koch, Katie; Powell, Alvin; Walsh, Colleen (May 26, 2011). "Harvard awards 9 honorary degrees". Harvard Gazette. Harvard University. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- ^ Reilly, Mollie (October 28, 2013). "The Women Of The Supreme Court Now Have The Badass Portrait They Deserve". The Huffington Post. Retrieved November 2, 2015.

- ^ "Jeff's New Toy – Clarence Videos". Cartoonnetwork.com. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ Lavender, Paige (May 4, 2015). "'Ruth Bader Ginsburg' Brings The Sass On SNL". The Huffington Post. Retrieved November 4, 2015.

- ^ Waldman, Paul (November 28, 2014). "Why the Supreme Court should be the biggest issue of the 2016 campaign". Washington Post. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ Alman, Ashley (January 16, 2015). "This Badass Tattoo Takes Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fandom To New Levels". Huffington Post. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ Lithwick, Dahlia (March 16, 2015). "Justice LOLZ Grumpycat Notorious R.B.G." Slate. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

Further reading

- Bayer, Linda N. Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2000. ISBN 978-0-791-05287-7 OCLC 42771306

- Campbell, Amy Leigh, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Raising the Bar: Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the ACLU Women's Rights Project. Princeton, NJ: Xlibris Corporation, 2003. ISBN 978-1-413-42741-7 OCLC 56980906

- Clinton, Bill. My Life. New York: Vintage Books, 2005. pp. 524–5, 941. ISBN 978-1-400-04393-4 OCLC 233703142

- Garner, Bryan A. Garner on Language and Writing. Chicago: American Bar Association, 2009. Forward by Ruth Bader Ginsburg. ISBN 978-1-590-31588-0 OCLC 310224965

- Moritz College of Law. 2009. "The Jurisprudence of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Discussion of Fifteen Years on the U.S. Supreme Court: Symposium." Ohio State Law Journal. 70, no. 4: 797-1126. ISSN 0048-1572 OCLC 676694369

- Ginsburg, Ruth Bader, et al. Essays in Honor of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Law School, 2013. OCLC 839314921

- Carmon, Irin, and Shana Knizhnik. Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. New York, Dey Street, William Morrow Publishers, 2015. ISBN 978-0-062-41583-7 OCLC 913957624

- Dodson, Scott. The Legacy of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-1-107-06246-7 OCLC 897881843

- Hirshman, Linda R. Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World. New York: HarperCollins, 2015. ISBN 978-0-062-23848-1 OCLC 907678612

External links

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg papers at the Library of Congress OCLC 70984211

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg at Ballotpedia

- Issue positions and quotes at OnTheIssues

- Voices on Antisemitism: Interview with Ruth Bader Ginsburg from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

- Ruth Bader Ginsburg, video produced by Makers: Women Who Make America

Template:Start U.S. Supreme Court composition Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1993–1994 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 1994–2005 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition CJ Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition court lifespan Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2005–2006 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2006–2009 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2009–2010 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2010–2016 Template:U.S. Supreme Court composition 2016–present Template:End U.S. Supreme Court composition

- 1933 births

- Living people

- 20th-century judges

- 21st-century judges

- American Civil Liberties Union people

- American Jews

- American legal scholars

- American women judges

- American women lawyers

- Colorectal cancer survivors

- Columbia Law School alumni

- Columbia University faculty

- Constitutional court women judges

- Cornell University alumni

- Harvard Law School alumni

- Jewish scholars

- Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit

- New York Democrats

- New York lawyers

- Pancreatic cancer survivors

- People from Brooklyn

- People with cancer

- Phi Kappa Phi

- Rutgers School of Law–Newark faculty

- Tulane University Law School faculty

- United States court of appeals judges appointed by Jimmy Carter

- United States federal judges appointed by Bill Clinton

- United States Supreme Court justices