Shashanka

| Shashanka | |

|---|---|

| Gauda king | |

| Reign | 590 CE - 625 CE |

| Predecessor | Mahasenagupta |

| History of Bengal |

|---|

|

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

King Shashanka (Template:Lang-bn Shôshangko) created the first separate political entity in a unified Bengal, called the Gauda Kingdom and is a major figure in Bengali history. He reigned in 7th century AD, and some historians place his rule approximately between 590 AD and 625 AD. He is the contemporary of Harsha and of Bhaskar Varman of Kamarupa. His capital was at Karnasubarna, in present-day Murshidabad in West Bengal. The development of the Bengali calendar is often attributed to Shashanka because the starting date falls within his reign.[1][2][3]

Contemporary sources

There are several major contemporary sources of information on his life, including copperplates from his vassal Madhavavarma (king of Ganjam), copperplates of his rivals Harsha and Bhaskaravarman, the accounts of Banabhatta, who was a bard in the court of Harsha, and of the Chinese monk Xuanzang, and also coins minted in Shashanka's reign.

Extent of kingdom

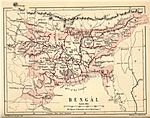

While Shashanka was known and referred to as the Lord of Gauda, his kingdom included more than just that region. By the end of his reign, his domain stretched from Vanga to Bhuvanesha while in the east, his kingdom bordered Kamarupa. Prior to Shashanka, Bengal was divided into three regions, Banga, Samatata and Gauda and was ruled by a feeble ruler belonging to the Later Gupta dynasty, Mahasenagupta. Shashanka was one of his chieftains who rose to power taking the advantage of the weak ruler. After the death of Mahasenagupta, Shashanka drove the later Guptas and other prominent nobles out of the region and established his own kingdom with a capital at Karnasubarna.

Oppression of Buddhism

Banabhatta described Shashanka as the "vile Gauda serpent", and elaborated that Shashanka has destroyed the Buddhist stupas of Bengal and declared an award of hundred gold coins for the head of every Buddhist monk in his kingdom. However Ramesh Chandra Majumdar attempted to acquit Shashanka and the Brahmins of his reign of such deeds because Xuanzang and Banabhatta were patronised by Shashanka's enemy, Harsha, and that Xuanzang was a Buddhist.[4] Despite this, the only evidence for the justification of conflict between Shashanka and Harsha is Xuanzang, who explained that Harsha's campaign against Shashanka was to "raise Buddhism from the ruin into which it had been brough by the king of Karnasuvarna" and that Shashanka wished to replace Buddhism with Shaivism.[5] As such, Radhagovinda Basak claims that there is no reason not to believe that Shashanka carried out a violent anti-Buddhist persecution.[6] Majumdar's opinion is further called into question in his denial of the anti-Buddhist persecutions reported in the last chapter of the Mañjuśrīmūlakalpa, which Kashi Prasad Jayaswal had deemed to indicate a serious attempt by Shashanka to destroy Buddhism in the spirit of "orthodox revivalism",[7] when he wrote that it is "unsafe to accept the statements recorded in this book as historical," and his minimization of the Sena persecutions of Buddhists.[8]

War with Harsha

Shashanka and his allies fought a major war with the then emperor of Thanesar, Harsha, and his allies. The result of the battle was inconclusive as Shashanka is documented to have retained dominion over his lands. The king of Malwa, Devgupta had an enmity with the ruler of Kannauj, Grahavarman who was also the brother-in-law of the Vardhan princes, by his marriage with the princess of Thanesar, Rajyashri. Devgupta attacked Kannauj and killed Grahavarman in the battle and imprisoned his wife Rajyashri. Rajyavardhana had recently become king in Thanesar upon the death of his father, Prabhakarvardhana. Rajyavardhana marched towards Kannauj to avenge the death of his brother-in-law. The battle was followed by the sudden assassination of Rajyavardhana. No conclusive evidence exists but it is possible that Shashanka, who joined the battle as an ally of Devgupta, murdered him. The only source available in this matter is the Harshacharita by Banabhatta, who was a childhood friend and constant companion of Harsha; neither of these men were present at the death.

Harsha succeeded his brother as ruler of Thanesar and he once again gathered the army and attacked Kannauj. Though the results are not known clearly, but it is evident that Devgupta and Shashanka had to retreat from Kannauj. Shashanka continued to rule Gauda with frequent attacks from Harsha which he is known to have faced bravely.

Legacy

Following his death, Shashanka was succeeded by his son, Manava, who ruled the kingdom for eight months. However Gauda was soon divided amongst Harsha and Bhaskarvarmana of Kamroop, the latter even managing to conquer Karnasuvarna.

See also

References

- ^ "Shashanka". Banglapedia. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ^ "Shashanka Dynasty". indianmirror.com. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - ^ Hermann Kulke, Dietmar Rothermund, A History of India, ISBN 0203443454

- ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1943). History of Bengal. Dacca: University of Dacca. pp. 73–74.

- ^ Sharma, Baijnath (1970). Harṣa and His Times. Sushma Prakashan. p. 157.

- ^ Basak, Radhagovinda (1967). The History of North-Eastern India Extending from the Foundation of the Gupta Empire to the Rise of the Pala Dynasty of Bengal (c. A.D. 320-760). Sambodhi Publications. p. 134.

- ^ Jayaswal, Kashi Prasad (1937). History of India. Lahore. p. 51.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1943). History of Bengal. Dacca: University of Dacca. p. 64.

Further Reading

- R. C. Majumdar, History of Bengal, Dacca, 1943, pp 58–68

- Sudhir R Das, Rajbadidanga, Calcutta, 1962

- P. K. Bhattacharyya, Two Interesting Coins of Shashanka, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, London, 2, 1979

External links

- Shashanka from Banglapedia