South Island

Nickname: The Mainland | |

|---|---|

| |

| Geography | |

| Location | Oceania |

| Coordinates | 43°59′S 170°27′E / 43.983°S 170.450°E |

| Archipelago | New Zealand |

| Area | 150,437 km2 (58,084 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 12th |

| Length | 840 km (522 mi) |

| Coastline | 5,842 km (3630.1 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 3,754 m (12316 ft) |

| Administration | |

New Zealand | |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | South Islander |

| Population | 1,138,000 |

| Pop. density | 7.5/km2 (19.4/sq mi) |

The South Island (Māori: Te Wai Pounamu) is the larger of the two major islands of New Zealand, the other being the more populous North Island. It is bordered to the north by Cook Strait, to the west by the Tasman Sea, to the south and east by the Pacific Ocean. The territory of the South Island covers 150,437 square kilometres (58,084 sq mi)[1] and is influenced by a temperate climate.

The South Island is sometimes called the "Mainland". While it has a 33% larger landmass than the North Island, only 24% of New Zealand's 4.8 million inhabitants live in the South Island. In the early stages of European (Pākehā) settlement of the country, the South Island had the majority of the European population and wealth due to the 1860s gold rushes. The North Island population overtook the South in the early 20th century, with 56% of the population living in the North in 1911, and the drift north of people and businesses continued throughout the century.[2]

History

Classical Māori Period

Early inhabitants of the South Island were the Waitaha. They were largely absorbed via marriage and conquest by the Kāti Mamoe in the 16th century.[citation needed]

Ngāti Mamoe were in turn largely absorbed via marriage and conquest by the Ngāi Tahu who migrated south in the 17th century.[3] While today there is no distinct Ngati Mamoe organisation, many Ngai Tahu have Ngati Mamoe links in their whakapapa and, especially in the far south of the island.

Around the same time a group of Māori migrated to Rekohu (the Chatham Islands), where, by adapting to the local climate and the availability of resources, they developed a culture known as Moriori — related to but distinct from Māori culture in mainland New Zealand. A notable feature of the Moriori culture, an emphasis on pacifism, proved disadvantageous when Māori warriors arrived in the 1830s aboard a chartered European ship.[4]

In the early 18th century, Ngāi Tahu a Māori tribe who originated on the east coast of the North Island began migrating to the northern part of the South Island. There they and Kāti Mamoe fought Ngāi Tara and Rangitāne in the Wairau Valley. Ngāti Māmoe then ceded the east coast regions north of the Clarence River to Ngāi Tahu. Ngāi Tahu continued to push south, conquering Kaikoura. By the 1730s, Ngāi Tahu had settled in Canterbury, including Banks Peninsula. From there they spread further south and into the West Coast.[5]

In 1827-1828 Ngāti Toa under the leadership of Te Rauparaha successfully attacked Ngāi Tahu at Kaikoura. Ngāti Toa then visited Kaiapoi, ostensibly to trade. When they attacked their hosts, the well-prepared Ngāi Tahu killed all the leading Ngāti Toa chiefs except Te Rauparaha. Te Rauparaha returned to his Kapiti Island stronghold. In November 1830 Te Rauparaha persuaded Captain John Stewart of the brig Elizabeth to carry him and his warriors in secret to Akaroa, where by subterfuge they captured the leading Ngāi Tahu chief, Te Maiharanui, and his wife and daughter. After destroying Te Maiharanui's village they took their captives to Kapiti and killed them. John Stewart, though arrested and sent to trial in Sydney as an accomplice to murder, nevertheless escaped conviction.[5]

In the summer of 1831–1832 Te Rauparaha attacked the Kaiapoi pā (fortified village). After a three-month siege, a fire in the pā allowed Ngāti Toa to overcome it. They then attacked Ngāi Tahu on Banks Peninsula and took the pā at Onawe. In 1832-33 Ngāi Tahu retaliated under the leadership of Tuhawaiki and others, attacking Ngāti Toa at Lake Grassmere. Ngāi Tahu prevailed, and killed many Ngāti Toa, although Te Rauparaha again escaped. Fighting continued for a year or so, with Ngāi Tahu maintaining the upper hand. Ngāti Toa never again made a major incursion into Ngāi Tahu territory.[5] By 1839 Ngāi Tahu and Ngāti Toa established peace and Te Rauparaha released the Ngāi Tahu captives he held. Formal marriages between the leading families in the two tribes sealed the peace.

European Discovery

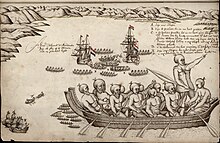

The first Europeans known to reach the South Island were the crew of Dutch explorer Abel Tasman who arrived in his ships Heemskerck and Zeehaen. In December 1642, Tasman anchored at the northern end of the island in Golden Bay which he named Moordenaar's Bay (Murderers Bay) before sailing northward to Tonga following a clash with Māori. Tasman sketched sections of the two main islands' west coasts. Tasman called them Staten Landt, after the States-General of the Netherlands, and that name appeared on his first maps of the country. Dutch cartographers changed the name to Nova Zeelandia in Latin, from Nieuw Zeeland, after the Dutch province of Zeeland. It was subsequently Anglicised as New Zealand by British naval captain James Cook of HM Bark Endeavour who visited the islands more than 100 years after Tasman during (1769–1770).

The first European settlement in the South Island was founded at Bluff in 1823 by James Spencer a veteran of the Battle of Waterloo.[6]

In January 1827, the French explorer Jules Dumont d'Urville arrived in Tasman Bay on the corvette Astrolabe. A number of landmarks around Tasman Bay were named by d'Urville and his crew including d'Urville Island, French Pass and Torrent Bay.

French Intentions

For years French writers and politicians had been urging that Britain should not be left to monopolise New Zealand. Some had suggested that even if Britain took the North Island, there was no reason why France should not colonise the South. When news of the success of the French whaling fleet in New Zealand waters in the 1838 season reached France in 1839, a solid commercial project was added to all the others — a project which its promoters who had land to sell, hoped would develop into a scheme for effective French colonisation.

Leaving France at the end of 1837 and sailing by way of the Cape of Good Hope, the French vessel Cachalot reached New Zealand waters in April 1838. For some time she was whaling off-shore, near the Chatham Islands, but in May came to Banks Peninsula. With them, to protect their interests, and to act as arbiter in any disputes, was the French corvette Héroine, commanded by captain Jean-Baptiste Cécille, which reached Akaroa in June. Cécille occupied much of the time of his officers and crew in making accurate charts of the harbours, first of all of Akaroa and then of Port Cooper (which he named Tokolabo) and Port Levy. At Port Cooper he established an observatory on shore in the bay just inside the heads, now called Little Port Cooper, but for which his name was ‘Waita’.

Little Port Cooper was used as an anchorage by most of the French ships working from Port Cooper in 1838 and in subsequent years, and it was apparently there that Langlois anchored when the Cachalot came into harbour in July 1838. While at Port Cooper, Langlois negotiated with the Māori for the purchase of the whole of Banks Peninsula, and a deed of sale was entered into on 2 August. The deed was signed by 11 Māori who claimed to be the owners of the whole of Banks Peninsula, although they lived at Port Cooper. Their leader was the chief Taikare, known as King Chigary. The total payment was to be 1000 Francs (then equivalent to 40 Pounds), a first installment of goods to the value of 150 Francs to be paid immediately and the balance when Langlois took possession of the property. This first instalment comprised a woollen overcoat, six pairs of linen trousers, a dozen waterproof hats, two pairs of shoes, a pistol, two woollen shirts, and a waterproof coat.

The territory transferred was defined as ‘Banks Peninsula and its dependencies’, only burial grounds being reserved for the Māori[6]. Langlois considered that he had purchased 30,000 acres (120 km2) but the total area is nearer 300,000 acres (1,200 km2). At the time of the execution of the deed, Captain Cécille subsequently and enthusiastically hoisted the French Flag on shore and issued a declaration of French sovereignty over Banks Peninsula. At the end of the 1838 whaling season Langlois left New Zealand waters, and on arriving in France some time after June 1839, set to work to market the property which he had bought from the Māori. He succeeded in interesting the marquis de las Marismas Aguado, a financier who had considerable influence with the Government. The Marquis set out to enlist support in Bordeaux for the formation of a company to exploit the property represented by Langlois's deed: the purpose of that settlement would be to establish on Banks Peninsula a settlement to serve as a base for French whaleships and other vessels in the Pacific. The difficulties of this first stage of the negotiations, in which rather too much dependency was placed on government action and aid, caused the Marquis to withdraw from the project[7].

On 13 October, Langlois also approached Admiral Duperré and Marshall Soult (President of the Council), stating that he had promises of support from Le Havre and that he would be able to make an offer acceptable to the Government. Almost at the same time, another influential financier, the Ducs Decazes, informed that the Bordeaux group was prepared to support the project. Finally the members of the Bordeaux group, joined with others from Nantes reached an agreement with Langlois, and on 8 November 1839, ‘La Compagnie de Bordeaux et de nantes pour la Colonisation de l’Île du Sud de la Nouvelle Zélande et ses Dépendances’ presented its petition to the Government. The company had a capital of one million Francs. Langlois received one-fifth interest in the company [8] in return for transferring to it all rights deriving from his deed of purchase.

The proposals were then examined by a commission of the Ministry of Marine, including Captains Petit-Thouars, J-B Cécille, and Roy, all of whom had special experience of the Pacific and of the supervision of French whaling interests. A draft agreement was worked out by the commissioners and the company's representatives which was approved on 11 December by the King, and by Marshall Soult, Admiral Duperré, and the Minister of Agriculture and Commerce.

Port Louis-Philippe (Akaroa) was named as the site of the settlement proposed in this agreement, in terms of which the Government undertook to make available to the Company the 550-ton storeship Mahé, renamed Comte-de-Paris to provide 17 months rations for 80 men; to consider the properties of the French colonists as French properties and the colonists themselves as French subjects, and to treat the produce of their crops as if they were of French origin. To protect the colonists, a warship would be sent out in advance of the emigrant ship, and its commander would exercise the powers of ‘Commissaire du Roi’. The ports of the settlement were to be free to French ships for a term of 15 years. One-fourth of all the lands acquired were to be reserved to the Crown for the building of ports, hospitals and shipyards[9]. The functions of the company as finally announced on 5 February 1840, were to buy land in New Zealand, to colonise the lands already bought in 1838 by Langlois, and to engage in the whale fishery.

Langlois also received two sets of instructions, one from Soult as Minister of Foreign Affairs, and one from Duperré as Minister of Marine. The texts read: "You will see to it that possession is taken in the name of France of all establishments formed in the Southern Island of New Zealand, and that the flag is flown upon them. You should also win over the chief Te Rauparaha and induce him to sell the lands under his control in the northern part of the South Island. There is great advantage in setting up establishments in various parts of the Island for acquisitions [of territory] will only go unchallenged where there is effective act of possession."

The colony at Akaroa was to be merely the starting point of the acquisition for France of a much larger portion of the South Island. This letter also made it clear that an extension of the proposed colony to include a penal settlement at the Chatham Islands was envisaged: ‘The King is still preoccupied with the idea and with the necessity of a place of deportation. He has strongly urged me not to leave his Ministers in peace until they have introduced a bill for the expedition to Chatham Island.’[10], Lavaud stated in reply that he thought it better for the penal settlement to be at Banks Peninsula, because of the remoteness of the Chathams and the lack of suitable anchorage there.

Meanwhile a small body of emigrants ‘of the peasant and labouring classes’ were enrolled. Each man was promised a grant of 5 acres (20,000 m2) of land, with half that area for boys between the age of ten and 15 years. They were to be provided with their rations for a period of about a year after their arrival in the colony, and were to be furnished with arms. By January 1840, 63 emigrants were assembled at Rochefort. Six were described as Germans. The total comprised 14 married men and their families and 19 single men and youths. Even after the emigrants were assembled there were considerable delays in getting the ships away. Lavaud sailed on the corvette Aube on 19 February 1840; the Comte-de-Paris, commanded by Langlois, and with the French immigrants on board, made a false start on 6 March and after going aground, finally got away on 20 March. Because of the late departure of the ships, the French expedition was doomed to failure from the outset.

The reason why the Aube sailed ahead of the Comte-de-Paris was to ‘gain time for fear the British might get the start of them’[11] Yet the New Zealand Company's survey ship Tory had sailed from Plymouth on 12 May 1839, before Langlois and his associates had made their first approach to the French government, and as early as June the British Government was considering sending Captain William Hobson to act as Lieutenant-Governor over such parts of New Zealand as might be acquired from the Māori. Hobson was notified of his appointment in August. He arrived at the Bay of Islands on 29 January 1840, and on 6 February the first signatures were placed on the Treaty of Waitangi. At that date, neither of the French ships had left France. While they were still on the high seas, in May 1840 Hobson proclaimed British sovereignty over the South Island by virtue of Captain Cook's discovery. The same month the H.M.S. Herald arrived at Akaroa, bringing Major T. Bunbury, who was carrying a copy of the Treaty of Waitangi for signature by the southern chiefs. At Akaroa it was signed by two chiefs, Iwikau and Tikao. Three weeks later at Cloudy Bay, Bunbury made a declaration of British sovereignty over the whole of the South Island, based upon the cession by the chiefs as signatories to the Treaty of Waitangi. It was not until 19 August that the French colonists were landed at Akaroa.

Much was done in getting the French settlers established. Allotments were laid out for them to the West of the stream where they had landed, in what is now known as the French town. As enough open land on the foreshore could not be found at all, the six Germans were alloted sections on the next bay to the west, now known as Takamatua, but until 1915 was called German Bay. The total area of the land taken up under the Nanto-Bordelaise Company at this time was 107 acres (0.43 km2). Although they had no animals, the colonists were able to plant and prepare their gardens. In the following year de Belligny obtained four working Bullocks from Sydney. Vegetable seeds and a number of young fruit trees — apples, pears, mulberry and nuts — as well as grape vines, had survived the voyage from France. Although Lavaud mentions that the ‘menagerie’ placed on board the Aube at Brest included not only the cattle, but geese, turkey cocks and hens, pigeons and even rabbits, it is not clear whether any of these survived.

The colonists arrived at a good time of the year to begin cultivation wherever the ground was cleared of timber, and within the first six weeks most of them had started their gardens. It was too late to sow grain, but they got their potatoes in, and sowed their vegetable seeds. Lavaud started at French Farm a larger garden to supply the needs of his crew. The colonists built their first rough huts, either of rough timber, or of wattle-and-daub. The spiritual needs of the settlement were cared for by the priests of the Catholic Mission, Fathers Comte and Tripe, one ministering to Maori and the other to Europeans.

European Settlement

When Britain annexed New Zealand in 1840, the South Island briefly became a part of New South Wales.[7] This annexation was in response to France’s attempts to colonise the South Island at Akaroa[8] and the New Zealand Company attempts to establish a separate colony in Wellington, and so Lieutenant-Governor William Hobson declared British sovereignty over all of New Zealand on 21 May 1840 (the North Island by treaty and the South by discovery).[9]

On 17 June 1843, Māori natives and the British settlers clashed at Wairau in what became known as the Wairau Affray. Also known as the Wairau Massacre in most older texts, it was the first serious clash of arms between the two parties after the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi and the only one to take place in the South Island. Four Māori died and three were wounded in the incident, while among the Europeans the toll was 22 dead and five wounded. Twelve of the Europeans were shot dead or clubbed to death after surrendering to Māori who were pursuing them.[10]

The Otago Settlement, sponsored by the Free Church of Scotland, took concrete form in Otago in March 1848 with the arrival of the first two immigrant ships from Greenock (on the Firth of Clyde) — the John Wickliffe and the Philip Laing. Captain William Cargill, a veteran of the Peninsular War, served as the colony's first leader: Otago citizens subsequently elected him to the office of Superintendent of the Province of Otago.

While the North Island was convulsed by the Land Wars of the 1860s and 1870s, the South Island, with its low Māori population, was generally peaceful. In 1861 gold was discovered at Gabriel's Gully in Central Otago, sparking a gold rush. Dunedin became the wealthiest city in the country and many in the South Island resented financing the North Island’s wars. In 1865 Parliament voted on a Bill to make the South Island independent: it was defeated 17 to 31.

In the 1860s, several thousand Chinese men, mostly from the Guangdong province, migrated to New Zealand to work on the South Island goldfields. Although the first Chinese migrants had been invited by the Otago Provincial government they quickly became the target of hostility from white settlers and laws were enacted specifically to discourage them from coming to New Zealand.[11]

2010–2011 earthquakes

September 2010

An earthquake with magnitude 7.1 occurred in the South Island, New Zealand at Saturday 04:35 am local time, 4 September 2010 (16:35 UTC, 3 September 2010).[12] The earthquake occurred at a depth of 10 kilometres (6.2 mi), and there were no fatalities.

The epicentre was located 40 kilometres (25 mi) west of Christchurch; 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south-east of Darfield;[13] 190 kilometres (120 mi) south-southeast of Westport; 295 kilometres (183 mi) south-west of Wellington; and 320 kilometres (200 mi) north-northeast of Dunedin.

Sewers were damaged,[14] gas and water lines were broken, and power to up to 75% of the city was disrupted.[15] Among the facilities impacted by lack of power was the Christchurch Hospital, which was forced to use emergency generators in the immediate aftermath of the quake.[15]

A local state of emergency was declared at 10:16 am on 4 September for the city, and evacuations of parts were planned to begin later in the day.[16] People inside the Christchurch city centre were evacuated, and the city's central business district remained closed until 5 September .[17] A curfew from 7 pm on 4 September to 7 am on 5 September was put in place.[18] The New Zealand Army was also deployed to assist police and enforce the curfew. All schools were closed until 8 September so they could be checked.

Christchurch International Airport was closed following the earthquake and flights in and out of it cancelled. It reopened at 1:30 pm following inspection of the main runway.[19]

The earthquake was reported to have caused widespread damage and power outages. 63 aftershocks were also reported in the first 48 hours with three registering 5.2 magnitude. Christchurch residents reported chimneys falling in through roofs, cracked ceilings and collapsed brick walls.[20] The total insurance costs of this event were estimated to reach up to $11 billion according to the New Zealand Treasury.[21][22]

February 2011

A large aftershock of magnitude 6.3 occurred on 22 February 2011 at 12:51 pm. It was centred just to the north of Lyttelton, 10 kilometres south east of Christchurch, at a depth of 5 km.[23] Although lower on the moment magnitude scale than the quake of September 2010, the intensity and violence of the ground shaking was measured to be VIII on the MMI and among the strongest ever recorded globally in an urban area due to the shallowness and proximity of the epicentre.[24] Early assessments indicated that approximately one third of buildings in the Central Business District would have to be demolished.

In contrast to the September 2010 quake, the quake struck on a busy weekday afternoon. This, along with the strength of the quakes, and proximity to the city center resulted in the February earthquake causing the tragic deaths of 181 people.[25]

This event promptly resulted in the declaration of New Zealand's first National State of Emergency. Many buildings and landmarks were severely damaged, including the iconic 'Shag Rock' and Christchurch Cathedral.

Offers of assistance were made quickly by international bodies. Contingents of Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) soon arrived. Teams were provided by Australia, USA, Singapore, Britain, Taiwan, Japan, and China.

The Royal New Zealand Navy was involved immediately. The HMNZS Canterbury, which was docked at Lyttelton when the quake struck, was involved in providing local community assistance, in particular by providing hot meals.

After inspection, the runway at Christchurch airport was found to be in good order. Due to the demand of citizens wishing to leave the city, the national airline Air New Zealand, offered a $50 Domestic Standby airfare. The Air New Zealand CEO increased the domestic airline traffic from Christchurch to Wellington and Auckland. Thousands of people took up this offer to relocate temporarily in the wake of the event.

On 1 March at 12:51, a week after the tragedy, New Zealand observed a two minute silence.

June 2011

On 13 June 2011 at approximately 1:00 pm New Zealand time, Christchurch was again rocked by a magnitude 5.7 quake, followed by a magnitude 6.3 quake (initially thought to be 6.0) at 2:20 pm, centred in a similar location as the February quake with a depth of 6.0 kilometres. Dozens of aftershocks occurred over the following days, including several over magnitude 4.

Phone lines and power were lost in some suburbs, and liquefaction surfaced mainly in the eastern areas of the city which were worst affected following the aftershocks.[26] Many residents in and around the hillside suburb of Sumner self-evacuated.[27]

Further damage was reported to buildings inside the cordoned central business district, with an estimate of 75 additional buildings needing demolition.[28] Among the buildings further damaged was the Christchurch Cathedral, which lost its iconic Rose window,[29] a factor reducing the likelihood of the cathedral being restored.[30]

There was only one death recorded following the quake; however there were multiple injuries.

Naming and usage

Although the island has been known as the South Island for many years, the New Zealand Geographic Board has found that, along with the North Island, it has no official name. The board intends to make South Island the island's official name, along with an alternative Māori name. Although several Māori names have been used, Maori Language Commissioner Erima Henare sees Te Wai Pounamu as the most likely choice.[31] Said to mean "the Water(s) of Greenstone", this possibly evolved from Te Wāhi Pounamu "the Place Of Greenstone". The island is also known as Te Waka a Māui which means "Māui's Canoe". In Māori legend, the South Island existed first, as the boat of Maui, while the North Island was the fish that he caught.

In the 19th century, some maps named the South Island as Middle Island or New Munster, and the name South Island or New Leinster was used for today's Stewart Island/Rakiura. In 1907 the Minister for Lands gave instructions to the Land and Survey Department that the name Middle Island was not to be used in future. "South Island will be adhered to in all cases".[32]

In prose, the two main islands of New Zealand are called the North Island and the South Island, with the definite article. It is normal to use the preposition in rather than on.[33] Maps, headings, tables and adjectival expressions use South Island without "the".

Government and politics

The South Island has no separately represented country subdivision and is guaranteed 16 of the 69 electorates in the New Zealand House of Representatives. A two-tier structure constituted under the Local Government Act 2002 gives the South Island seven regional councils for the administration of regional environmental and transport matters and 25 territorial authorities that administer roads, sewerage, building consents, and other local matters. Four of the territorial councils (one city and three districts) also perform the functions of a regional council and are known as unitary authorities.

When New Zealand was separated from the colony of New South Wales in 1841 and established as a Crown colony in its own right, the Royal Charter effecting this provided that "the principal Islands, heretofore known as, or commonly called, the 'Northern Island', the 'Middle Island', and 'Stewart's Island', shall henceforward be designated and known respectively as 'New Ulster', 'New Munster', and 'New Leinster'".

These divisions were at first of geographical significance only, not used as a basis for the government of the colony, which was centralised in Auckland. New Munster consisted of the South Island and the southern portion of the North Island, up to the mouth of the Patea River. The name New Munster was given by the Governor of New Zealand, Captain William Hobson, in honour of Munster, the Irish province in which he was born.

The situation was altered in 1846 when the New Zealand Constitution Act 1846.[34] divided the colony into two provinces: New Ulster Province (the North Island), and New Munster Province (the South Island and Stewart Island). Each province had a Governor and Legislative and Executive Council, in addition to the Governor-in-Chief and Legislative and Executive Council for the whole colony. However, the 1846 Constitution Act was later suspended, and only the Provincial government provisions were implemented. Early in 1848 Edward John Eyre was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of New Munster. In 1851 the Provincial Legislative Councils were permitted to be partially elective.

The Provincial Council of New Munster had only one legislative session, in 1849, before it succumbed to the virulent attacks of settlers from Wellington. Governor Sir George Grey, sensible to the pressures, inspired an ordinance of the General Legislative Council under which new Legislative Councils would be established in each province with two-thirds of their members elected on a generous franchise. Grey implemented the ordinance with such deliberation that neither Council met before advice was received that the United Kingdom Parliament had passed the New Zealand Constitution Act 1852.

This act dissolved these provinces in 1853, after only seven years' existence, and New Munster was divided into the provinces of Canterbury, Nelson, and Otago. Each province had its own legislature known as a Provincial Council that elected its own Speaker and Superintendent.

Secession movements have surfaced several times in the South Island. A Premier of New Zealand, Sir Julius Vogel, was amongst the first people to make this call, which was voted on by the Parliament of New Zealand as early as 1865. The desire for the South Island to form a separate colony was one of the main factors in moving the capital of New Zealand from Auckland to Wellington that year.

Several South Island nationalist groups have emerged over recent years including the South Island Party with a pro-South agenda, fielded candidates in the 1999 General Election. Today, several internet based groups advocate their support for greater self determination.[35]

On 13 October 2010, South Island Mayors led by Bob Parker of Christchurch displayed united support for a Southern Mayoral Council. Supported by Waitaki Mayor Alex Familton and Invercargill Mayor Tim Shadbolt, Bob Parker said that increased cooperation and the forming of a new South Island-wide mayoral forum were essential to representing the island's interests in Wellington and countering the new Auckland Council.[36]

In February 2012, the South Island Strategic Alliance (SISA) involving nearly all the Councils of the South Island was formed. This group is made up of elected representatives and senior management from 12 councils and the Department of Internal Affairs. It will examine potential projects where there are real and achievable benefits, for example in roads, information technology and library services and then allocate the project to a group of willing council CEOs for progression.[37]

Administrative divisions

Local government regions

There are seven local government regions covering the South Island and all its adjacent islands and territorial waters. Four are governed by an elected regional council, while three are governed by territorial authorities (the second tier of local government) which also perform the functions of a regional council and thus are known as unitary authorities. There is one exception to this, Nelson City, is governed by an individual Territorial authority to its region (Tasman Region). The Chatham Islands Council is often counted by many as a unitary authority, but it is officially recognised as a part of the region of Canterbury.

Territorial authorities

There are 23 territorial authorities within the South Island: 4 city councils and 19 district councils. Four territorial authorities (Nelson City Council, Tasman and the Marlborough District Councils) also perform the functions of a regional council and thus are known as unitary authorities.

- ^ Population as of June 2018.

- ^ Total of Christchurch City and Banks Peninsula areas.

- ^ Includes Stewart Island and Solander Islands.

Political parties

This is a list of political parties, past and present, who have their headquarters in the South Island.

- Aotearoa Legalise Cannabis Party

- Imperial British Conservative Party

- National Democrats Party

- New Munster Party

- New Zealand Democratic Party

- New Zealand Progressive Party

- South Island Party

Law enforcement

Police

The New Zealand Police is the primary law enforcement agency of New Zealand including the South Island. Three decentralised Police Districts cover the entire South Island with each being commanded by a Superintendent and having a central station from which subsidiary and suburban stations are managed.[39] The Christchurch Police Communications Centre handles all emergency and general calls within the South Island.

The Tasman Police District covers 70,000 kilometres of territory, encompassing the northern and most of the western portion of the South Island. The West Coast alone spans the distance between Wellington and Auckland. There are 22 police stations in the Tasman District, with 6 being sole-charge - or one-person - stations. The Tasman Police District has a total of 302 sworn police officers and 57 civilian or nonsworn staff. Organisationally, the district has its headquarters in Nelson and has three distinct Areas each headed by an Inspector as its commander. The areas are Nelson Bays, West Coast and Marlborough.

The Canterbury Police District is based in Christchurch the largest city in the South Island and covers an area extending from the Conway River, (just south of Kaikoura), to the Waitaki River, south of Timaru.

The Southern Police District with its headquarters in Dunedin spans from Oamaru in the North through to Stewart Island in the far South covers the largest geographical area of any of the 12 police districts in New Zealand. The Southern District has three distinct Areas headed by Inspectors; Otago Rural, Southland and Dunedin.

Correctional facilities

Correctional facilities in the South Island are operated by the Department of Corrections as part of the South Island Prison Region. Christchurch Prison, also known as Paparua, is located in Templeton a satellite town of Christchurch. It accommodates up to 780 minimum, medium and high security male prisoners. It was built in 1925, and also includes a youth unit, a self-care unit and the Paparua Remand Centre (PRC), built in 1999 to replace the old Addington Prison. Christchurch Women's Prison, also located in Templeton, is a facility for women of all security classifications. It has the only maximum/medium security accommodation for women prisoners in New Zealand. It can accommodate up to 98 prisoners.

Rolleston prison is located in Rolleston, another satellite town of Christchurch. It accommodates around 320 male prisoners of minimum to low-medium security classifications and includes Kia Marama a sixty-bed unit that provides an intensive 9 month treatment programme for male child sex offenders. Invercargill Prison, in Invercargill, accommodates up to 172 minimum to low-medium security prisoners. Otago Corrections Facility is located near Milton and houses up to 335 minimum to high-medium security male prisoners.

Customs Service

The New Zealand Customs Service whose role is to provide border control and protect the community from potential risks arising from international trade and travel, as well as collecting duties and taxes on imports to the country has offices at Christchurch International Airport, Dunedin, Invercargill, Lyttelton and Nelson.[40]

People

Population

Compared to the more populated and multi-ethnic North Island, the South Island has a smaller, more homogeneous resident population of 1,138,000 (June 2018).[41] At the 2001 Census, over 91 percent of people in the South Island said they belong to the European ethnic group, compared with 80.1 percent for all of New Zealand.[42] According to the Statistics New Zealand Subnational Population Projections: 2006–2031; the South Island's population will increase by an average of 0.6 percent a year to 1,047,100 in 2011, 1,080,900 in 2016, 1,107,900 in 2021, 1,130,900 in 2026 and 1,149,400 in 2031.[43]

Urbanisation

| Cities and towns of the South Island by population | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| City/Town | Region | Population (2008) | City/Town | Region | Population (2008) | |||||

| 1 | Christchurch | Canterbury | 404,500 | 11 | Gore | Southland | 9,910 | |||

| 2 | Dunedin | Otago | 122,000 | 12 | Rangiora | Canterbury | 9,288 | |||

| 3 | Nelson | Nelson | 67,500 | 13 | Motueka | Tasman | 7,125 | |||

| 4 | Invercargill | Southland | 51,200 | 14 | Alexandra | Otago | 5,920 | |||

| 5 | Blenheim | Marlborough | 31,600 | 15 | Wanaka | Otago | 5,037 | |||

| 6 | Timaru | Canterbury | 29,100 | 16 | Cromwell | Otago | 4,080 | |||

| 7 | Ashburton | Canterbury | 20,200 | 17 | Balclutha | Otago | ~4,000 | |||

| 8 | Oamaru | Otago | 13,950 | 18 | Temuka | Canterbury | 3,981 | |||

| 9 | Queenstown | Otago | 10,442 | 19 | Westport | West Coast | ~3,900 | |||

| 10 | Greymouth | West Coast | 9,700 | 20 | Rolleston | Canterbury | 3,822 | |||

Economy

The South Island economy is strongly focused on tourism and primary industries like agriculture. The other main industry groups are manufacturing, mining, construction, energy supply, education, health and community services.

Energy

The South Island is a major centre for electricity generation, especially in the southern half of the island and especially from hydroelectricity. In 2010, the island generated 18,010 GWh of electricity, 41.5% of New Zealand's total electricity generation. Nearly all (98.7%) of the island's electricity is generated by hydroelectricity, with most of the remainder coming from wind generation.[44]

There are three large hydro schemes in the South Island: Waitaki, Clutha, and Manapouri, which combined produce nearly 92% of the island's electricity. The Waitaki River is the largest at 1738 MW of installed capacity. The Waitaki River is the largest hydroelectric scheme, consisting of nine powerhouses commissioned between 1936 and 1985, and generating approximately 7600 GWh annually, around 18% of New Zealand's electricity generation[45] and more than 30% of all its hydroelectricity.[46] The Clutha River has two major stations generating electricity: Clyde Dam (432 MW, commissioned 1992) and Roxburgh Dam (360 MW, commissioned 1962). Manapouri Power Station is an isolated station located in Southland, generating 730 MW of electricity and producing 4800 GWh annually - the largest single hydroelectric power station in the country.

While most of the electricity generated in the South Island is transported via the 220 kV grid (plus 110 kV and 66 kV connectors) to major demand centres, including Christchurch, Dunedin, and Tiwai Point Aluminium Smelter, around one-sixth of it is exported to the North Island to meet its large (and increasing) power demands via the HVDC Inter-Island link. The 611 km HVDC Inter-Island was commissioned in 1965, linking Benmore Dam on the Waitaki River in Southern Canterbury, with Haywards substation in Lower Hutt in the North island, with cables crossing Cook Strait between Fighting Bay and Oteranga Bay. While the majority of the time the South Island exports electricity to the North Island via the link, it is also used to import thermally-generated North Island electricity in years of low hydro levels.

Offshore oil and gas is likely to become an increasing important part of the South Island economy into the future. Origin Energy has formed a joint venture with Anadarko Petroleum, the second-largest independent US natural gas producer to begin drilling for oil in the Canterbury Basin off the coast of Dunedin. The 390 km2, Carrack/Caravel prospect has the potential to deliver more than the equivalent of 500,000,000 barrels (79,000,000 m3) of oil and gas. Market analyst, Greg Easton from Craigs Investment Partners commented that such a substantial find it could well turn Dunedin from the Edinburgh of the south to the Aberdeen of the south.[47]

The Great South Basin off the coast of Southland at over 500,000 km2 (covering an area 1.5 times New Zealand’s land mass) is one of New Zealand’s largest undeveloped offshore petroleum basins with prospects for both oil and gas. In July 2007 the New Zealand Government awarded oil and gas exploration permits for four areas of the Great South Basin, situated in the volatile waters off the Southern Coast of New Zealand. The three successful permit holders are:[48]

- a consortium led by ExxonMobil New Zealand (Exploration) Limited (USA) which includes local company Todd Exploration Limited (New Zealand);

- a consortium led by OMV New Zealand Limited (Austria) which includes PTTEP Offshore Investment Company Ltd (Thailand), Mitsui Exploration and Production Australia Pty Ltd (Japan); and

- Greymouth Petroleum Limited (New Zealand)

The sub-national GDP of the South Island was estimated at US$27.8 billion in 2003, 21% of New Zealand's national GDP.[49]

Stock exchanges

Due to the gold rushes of the 1860s, the South Island had regional stock exchanges in Christchurch, Dunedin and Invercargill – all of which were affiliated in the Stock Exchange Association of New Zealand. However, in 1974 these regional exchanges were amalgamated to form one national stock exchange, the New Zealand Stock Exchange (NZSE). Separate trading floors operated in both Christchurch and Dunedin until the late 1980s. On 30 May 2003, New Zealand Stock Exchange Limited formally changed its name to New Zealand Exchange Limited, trading as NZX.

Today, the Deloitte South Island Index[50] is compiled quarterly from publicly available information provided by NZX, Unlisted and Bloomberg. It is a summary of the movements in market capitalisation of each South Island based listed company. A company is included in the Index where either its registered office and/or a substantial portion of its operations are focused on the South Island.

Trade unions

There are several South Island based trade union organisations. They are:

- Furniture, Manufacturing & Associated Workers Union

- New Zealand Building Trades Union

- New Zealand Meat & Related Trades Workers Union

- Southern Amalgamated Workers' Union

Tourism

Tourism is a huge earner for the South Island. Popular tourist activities include sightseeing, adventure tourism, such as glacier climbing and Bungee jumping, tramping (hiking), kayaking, and camping. Numerous walking and hiking paths such as the Milford Track, have huge international recognition.

An increase in direct international flights to Christchurch, Dunedin and Queenstown has boosted the number of overseas tourists.

Fiordland National Park, Abel Tasman National Park, Westland National Park, Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park, Queenstown, Kaikoura and the Marlborough Sounds are regarded as the main tourism destinations in the South Island and amongst the Top 10 destinations in New Zealand.[51]

Ski areas and resorts

This is a list of ski areas and resorts in the South Island.

| Name | Location | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Awakino ski area | Otago | Club Skifield |

| Broken River | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Cardrona Alpine Resort | Otago | |

| Coronet Peak | Otago | |

| Craigieburn Valley | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Fox Peak | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Hanmer Springs Ski Area | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Invincible Snowfields | Otago | Helicopter access only |

| Mount Cheeseman | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Mount Dobson | Canterbury | |

| Mount Hutt | Canterbury | |

| Mount Olympus | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Mount Potts | Canterbury | Heliskiing and snowcatting only |

| Mount Robert | Tasman | Club Skifield |

| Ohau | Canterbury | |

| Porter Ski Area | Canterbury | |

| Rainbow | Tasman | |

| The Remarkables | Otago | |

| Round Hill | Canterbury | |

| Snow Farm | Otago | cross-country skiing |

| Snow Park | Otago | |

| Tasman Glacier | Canterbury | Heliskiing |

| Temple Basin | Canterbury | Club Skifield |

| Treble Cone | Otago |

Transport

.

Road transport

The South Island has a State Highway network of 4,921 km.

Rail transport

The South Island's railway network has two main lines, two secondary lines, and a few branch lines. The Main North Line from Picton to Christchurch and the Main South Line from Lyttelton to Invercargill via Dunedin together comprise the South Island Main Trunk Railway. The secondary Midland Line branches from the Main South Line in Rolleston and passes through the Southern Alps via the Otira Tunnel to the West Coast and its terminus in Greymouth. In Stillwater, it meets the other secondary route, the Stillwater - Westport Line, which now includes the Ngakawau Branch.

A number of other secondary routes are now closed, including the Otago Central Railway, the isolated Nelson Section, and the interdependent Waimea Plains Railway and Kingston Branch. An expansive network of branch lines once existed, especially in Canterbury, Otago, and Southland, but these are now almost completely closed. The branch lines that remain in operation serve ports (Bluff Branch and Port Chalmers Branch), coal mines (Ohai Branch and Rapahoe Branch), and a dairying factory (Hokitika Branch). The first 64 km of the Otago Central Railway remain in operation for tourist trains run by the Taieri Gorge Railway (TGR). The most significant freight is coal from West Coast mines to the port of Lyttelton for export.

Passenger services were once extensive. Commuter trains operated multiple routes around Christchurch and Dunedin, plus a service between Invercargill and Bluff. Due to substantial losses, these were cancelled between the late 1960s and early 1980s. The final services to operate ran between Dunedin's City Centre and the suburb of Mosgiel, and they ceased in 1982.[52] Regional passenger trains were once extensive, but are now limited to the TranzCoastal from Christchurch to Picton and the TranzAlpine from Christchurch to Greymouth.

The Southerner between Christchurch and Invercargill, once the flagship of the network, was cancelled on 10 February 2002. Subsequently, the architecturally significant Dunedin Railway Station has been used solely by the TGR's tourist trains, the Taieri Gorge Limited along the Otago Central Railway and the Seasider to Palmerston. Rural passenger services on branch lines were provided by mixed trains and Vulcan/88 seater railcars but the mixeds had largely ceased to exist by the 1950s and the railcars were withdrawn in the mid-1970s.

The South Island saw the final use of steam locomotives in New Zealand. Locomotives belonging to classes long withdrawn elsewhere continued to operate on West Coast branches until the very late 1960s, when they were displaced by DJ class diesels. In comparison to most countries, where steam locomotives were last used on insubstantial rural and industrial operations, the very last services run by steam locomotives were the premier expresses between Christchurch and Invercargill: the South Island Limited until 1970 and the Friday and Sunday night services until 1971. This was due to the carriages being steam-heated. The final steam-hauled service in New Zealand, headed by a member of the JA class, ran on 26 October 1971.[53]

Water transport

The South Island is separated from the North Island by Cook Strait, which is 24 km wide at its narrowest point, and requires a 70 km ferry trip to cross.

Dunedin was the headquarters of the Union Steam Ship Company, once the largest shipping company in the Southern Hemisphere.

Ports and harbours

- Container ports: Lyttelton (Christchurch), Port Chalmers (Dunedin)

- Other ports: Nelson, Picton, Westport, Greymouth, Timaru, Bluff.

- Harbours: Akaroa Harbour, Otago Harbour, Halfmoon Bay (Stewart Island/Rakiura), Milford Sound.

- Freshwater: Queenstown and Kingston (Lake Wakatipu), Te Anau and Manapouri (Lake Manapouri)

Air transport

Airports

Geography

The South Island, with an area of 150,437 km2 (58,084 sq mi), is the largest land mass of New Zealand; it contains about one quarter of the New Zealand population and is the world's 12th-largest island. It is divided along its length by the Southern Alps, the highest peak of which is Aoraki/Mount Cook at 3754 metres (12,316 ft). There are eighteen peaks of more than 3000 metres (9800 ft) in the South Island. The east side of the island is home to the Canterbury Plains while the West Coast is famous for its rough coastlines, very high proportion of native bush, and Fox and Franz Josef Glaciers. The dramatic landscape of the South Island has made it a popular location for the production of several films, including the Lord of the Rings trilogy and the The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Geology

On 4 September 2010, the South Island was struck by a 7.1 magnitude earthquake, which caused extensive damage, several power outages, and many reports of aftershocks. Five and a half months later, the 22 February Christchurch earthquake of 6.3 magnitude caused far more additional damage in Christchurch, resulting in 181 deaths.[54] This quake struck at about lunchtime and was centred closer at Lyttelton, and shallower than the prior quake, consequently causing extensive damage.[55]

Climate

The climate in the South Island is mostly temperate. The Mean temperature for the South Island is 8 °C (46 °F).[56] January and February are the warmest months while July is the coldest. Historical maxima and minima are 42.4 °C (108.3 °F) in Rangiora, Canterbury and −21.6 °C (−6.9 °F) in Ophir, Otago.[57]

Conditions vary sharply across the regions from extremely wet on the West Coast to semi-arid in the Mackenzie Basin of inland Canterbury. Most areas have between 600 and 1600 mm of rainfall with the most rain along the West Coast and the least rain on the East Coast, predominantly on the Canterbury Plains. Christchurch is the driest city receiving about 640 mm (25 in) of rain per year. The southern and south-western parts of South Island have a cooler and cloudier climate, with around 1400–1600 hours of sunshine annually; the northern and north-eastern parts of the South Island are the sunniest areas and receive approximately 2400–2500 hours.[58]

Protected areas of the South Island

Forest Parks

There are six Forest Parks in the South Island which are on public land administered by the Department of Conservation.

- Catlins Forest Park

- Situated in the Southland region.

- Craigieburn Forest Park

- Situated in the Canterbury region, its boundaries lie in part alongside State Highway 73 and is adjacent to the eastern flanks of the Southern Alps. The Broken River Ski Area and the Craigieburn Valley Ski Area lie within its borders. The New Zealand Forest Service had used the area as an experimental forestry area and there is now an environmental issue with the spread of wilding conifers.

- Hanmer Forest Park

- Situated in the Canterbury region.

- Lake Sumner Forest Park

- Situated in the Canterbury region.

- Mount Richmond Forest Park

- Situated in the Marlborough region.

- Victoria Forest Park

- Situated in the West Coast region.

National parks

The South Island has ten national parks established under the National Parks Act 1980 and which are administered by the Department of Conservation.

From north to south, the National Parks are:

- Kahurangi National Park

- (4,520 km², established 1996) Situated in the north-west of the South Island, Kahurangi comprises spectacular and remote country and includes the Heaphy Track. It has ancient landforms and unique flora and fauna. It is New Zealand's second largest national park.

- Abel Tasman National Park

- (225 km², established 1942) Has numerous tidal inlets and beaches of golden sand along the shores of Tasman Bay. It is New Zealand's smallest national park.

- Nelson Lakes National Park

- (1,018 km², established 1956) A rugged, mountainous area in Nelson Region. It extends southwards from the forested shores of Lake Rotoiti and Rotoroa to the Lewis Pass National Reserve.

- Paparoa National Park

- (306 km², established 1987) On the West Coast of the South Island between Westport and Greymouth. It includes the celebrated Pancake Rocks at Punakaiki.

- Arthur's Pass National Park

- (1,144 km², established 1929) A rugged and mountainous area straddling the main divide of the Southern Alps.

- Westland Tai Poutini National Park

- (1,175 km², established 1960) Extends from the highest peaks of the Southern Alps to a wild remote coastline. Included in the park are glaciers, scenic lakes and dense rainforest, plus remains of old gold mining towns along the coast.

- Aoraki/Mount Cook National Park

- (707 km², established 1953) An alpine park, containing New Zealand's highest mountain, Aoraki/Mount Cook (3,754 m) and its longest glacier, Tasman Glacier (29 km). A focus for mountaineering, ski touring and scenic flights, the park is an area of outstanding natural beauty. Together, the Mount Cook and Westland National Parks have been declared a World Heritage Site.

- Mount Aspiring National Park

- (3,555 km², established 1964) A complex of impressively glaciated mountain scenery centred on Mount Aspiring/Tititea (3,036 m), New Zealand's highest peak outside of the main divide.

- Fiordland National Park

- (12,519 km², established 1952) The largest national park in New Zealand and one of the largest in the world. The grandeur of its scenery, with its deep fiords, its lakes of glacial origin, its mountains and waterfalls, has earned it international recognition as a world heritage area.

- Rakiura National Park

- (1,500 km², established 2002) On Stewart Island/Rakiura.

Other Native Reserves and Parks

Birds

There are several bird species which are endemic to the South Island. They include the Kea, Great Spotted Kiwi, Okarito Brown Kiwi, South Island Kōkako, South Island Pied Oystercatcher, Malherbe's Parakeet, King Shag, Takahe, Black-fronted Tern, New Zealand Robin, Rock Wren, Wrybill, Yellowhead

Unfortunately many South Island bird species are now extinct, mainly due to predation by cats and rats introduced by humans. Extinct species include the South Island Goose, South Island Giant Moa and South Island Piopio.

Natural geographic features

Fiords

The South Island has 15 named maritime fiords which are all located in the southwest of the island in a mountainous area known as Fiordland. The spelling 'fiord' is used in New Zealand, although all the maritime fjords use the word Sound in their name instead.

A number of lakes in the Fiordland and Otago regions also fill glacial valleys. Lake Te Anau has three western arms which are fjords (and are named so). Lake McKerrow to the north of Milford Sound is a fjord with a silted-up mouth. Lake Wakatipu fills a large glacial valley, as do lakes Hakapoua, Poteriteri, Monowai and Hauroko in the far south of Fiordland. Lake Manapouri has fjords as its West, North and South arms.

The Marlborough Sounds, are a series of deep indentations in the coastline at the northern tip of the South Island, are in fact rias, drowned river valleys.

Glaciers

Most of New Zealand's glaciers are in the South Island. They are generally found in the Southern Alps near the Main Divide.

An inventory of South Island glaciers during the 1980s indicated there were about 3,155 glaciers with an area of at least one hectare (2.5 acres).[60] Approximately one sixth of these glaciers covered more than 10 hectares. These include the Fox and Franz Josef glaciers on the West Coast, and the Tasman, Hooker, Mueller and Murchison glaciers in the east.

Lakes

There are some 3,820 lakes in New Zealand with a surface area larger than one hectare. Much of the higher country in the South Island was covered by ice during the glacial periods of the last two million years. Advancing glaciers eroded large steep-sided valleys, and often carried piles of moraine (rocks and soil) that acted as natural dams. When the glaciers retreated, they left basins that are now filled by lakes. The level of most glacial lakes in the upper parts of the Waitaki and Clutha rivers are controlled for electricity generation. Hydroelectric reservoirs are common in South Canterbury and Central Otago, the largest of which is Lake Benmore, on the Waitaki River.

The South Island has 8 of New Zealand's 10 biggest lakes. They were formed by glaciers and include Lake Wakatipu, Lake Tekapo and Lake Manapouri. The deepest (462 m) is Lake Hauroko, in western Southland. It is the 16th deepest lake in the world. Millions of years ago, Central Otago had a huge lake – Lake Manuherikia. It was slowly filled in with mud, and fossils of fish and crocodiles have been found there.

Volcanoes

There are 4 extinct volcanoes in the South Island, all of which are located on the east coast.

Banks Peninsula forms the most prominent of these volcanic features. Geologically, the peninsula comprises the eroded remnants of two large shield volcanoes (Lyttelton formed first, then Akaroa). These formed due to intraplate volcanism between approximately eleven and eight million years ago (Miocene) on a continental crust. The peninsula formed as offshore islands, with the volcanoes reaching to about 1,500 m above sea level. Two dominant craters formed Lyttelton and Akaroa Harbours.

The Canterbury Plains formed from the erosion of the Southern Alps (an extensive and high mountain range caused by the meeting of the Indo-Australian and Pacific tectonic plates) and from the alluvial fans created by large braided rivers. These plains reach their widest point where they meet the hilly sub-region of Banks Peninsula. A layer of loess, a rather unstable fine silt deposited by the foehn winds which bluster across the plains, covers the northern and western flanks of the peninsula. The portion of crater rim lying between Lyttelton Harbour and Christchurch city forms the Port Hills.

The Otago Harbour was formed from the drowned remnants of a giant shield volcano, centred close to what is now the town of Port Chalmers. The remains of this violent origin can be seen in the basalt of the surrounding hills. The last eruptive phase ended some ten million years ago, leaving the prominent peak of Mount Cargill.

Timaru was constructed on rolling hills created from the lava flows of the extinct Mount Horrible, which last erupted many thousands of years ago.

Te Wāhipounamu World Heritage site

Te Wāhipounamu (Māori for "the place of greenstone") is a World Heritage site in the south west corner of the South Island.[61]

Inscribed on the World Heritage List in 1990 it covers 26,000 km² and incorporates the Aoraki/Mount Cook, the Fiordland, the Mount Aspiring and the Westland National Parks.

It is thought to contain some of the best modern representations of the original flora and fauna present in Gondwanaland, one of the reasons for listing as a World Heritage site.

Education

The South Island has several tertiary level institutions:

Healthcare

Healthcare in the South Island is provided by five District Health Boards (DHBs). Organized around geographical areas of varying population sizes, they are not coterminous with the Local Government Regions.

| Name | Area covered | Population[62] |

|---|---|---|

| Canterbury District Health Board (CDHB) | Ashburton District, Christchurch City, Hurunui District, Kaikoura District, Selwyn District, Waimakariri District | 491,000 |

| Southern District Health Board (Southern DHB) | Invercargill City, Gore District, Southland District, Dunedin City, Waitaki District, Central Otago District, Queenstown Lakes District, Clutha District. | 300,400 |

| Nelson Marlborough District Health Board (NMDHB) | Marlborough District, Nelson City, Tasman District, | 135,000 |

| South Canterbury District Health Board (SCDHB) | Mackenzie District, Timaru District, Waimate District | 55,000 |

| West Coast District Health Board (WCDHB) | Buller District, Grey District, Westland District | 32,000 |

Emergency medical services

There are several air ambulance and rescue helicopter services operating throughout the South Island.[63]

- The Lake Districts Air Rescue Trust operates two AS350BA Squirrel's and an AS355 Squirrel from Queenstown Airport.

- The New Zealand Flying Doctor Service operates a Cessna 421 Golden Eagle and a Cessna Conquest C441 from Christchurch International Airport.[64]

- The Otago Rescue Helicopter Trust operates a MBB/Kawasaki BK 117 from Taieri Aerodrome near Mosgiel.

- The Solid Energy Rescue Helicopter Trust operates an AS350BA Squirrel from Greymouth.

- The Summit Rescue Helicopter Trust operates an AS350BA Squirrel from Nelson Airport.

- The Westpac Rescue Helicopter Trust operates a MBB/Kawasaki BK 117 and an AS350BA Squirrel from Christchurch International Airport.

Culture

Art

The South Island has contributed to the Arts in New Zealand and internationally through highly regarded artists such as Nigel Brown, Frances Hodgkins, Colin McCahon, Shona McFarlane, Peter McIntyre Grahame Sydney and Geoff Williams.

The University of Canterbury School of Fine Arts was founded in 1950.

South Island Art Galleries include:

Language

Parts of the South Island principally Southland and Otago are famous for its people speaking what is often referred to as the "Southland burr", a semi-rhotic, Scottish-influenced dialect of the English language.

Media

Newspapers

The South Island has ten daily newspapers and a large number of weekly community newspapers; major daily newspapers include the Ashburton Guardian, Greymouth Star, The Marlborough Express, The Nelson Mail, Oamaru Mail, Otago Daily Times, The Press, Southland Times, The Timaru Herald, and West Coast Times. The Press and Otago Daily Times, serving mainly Chritchurch and Dunedin respectively, are the South Islands major newspapers.

Television

The South Island has seven regional stations (either non-commercial public service or privately owned) that broadcast only in one region or city: 45 South TV, Channel 9, Canterbury Television, CUE, Mainland Television, Shine TV, and Visitor TV. These stations mainly broadcast free to air on UHF frequencies, however some are carried on subscription TV. Content ranges from local news, access broadcasts, satellite sourced news, tourist information and Christian programming to music videos.

Radio stations

A large number of radio stations serve communities throughout the South Island; these include independent stations, but many are owned by organisations such as Radio New Zealand, The Radio Network, and MediaWorks New Zealand.

Museums

- Bluff Maritime Museum

- Cadbury World

- Canterbury Museum

- Ferrymead Heritage Park

- Nelson Provincial Museum

- Olveston House

- Otago Museum

- Otago Settlers Museum

- Royal New Zealand Air Force Museum

- Southland Museum and Art Gallery

- World of Wearable Art

- Yaldhurst Museum

Religion

Anglicanism is strongest in Canterbury (the city of Christchurch having been founded as an Anglican settlement).

Catholicism is still has a noticeably strong presence on the West Coast, and in Kaikoura. The territorial authorities with the highest proportion of Catholics are Kaikoura (where they are 18.4% of the total population), Westland (18.3%), and Grey (17.8%).

Presbyterianism is strong in the lower South Island — the city of Dunedin was founded as a Presbyterian settlement, and many of the early settlers in the region were Scottish Presbyterians. The territorial authorities with the highest proportion of Presbyterians are Gore (where they are 30.9% of the total population), Clutha District (30.7%), and Southland (29.8%).

The first Muslims in New Zealand were Chinese gold diggers working in the Dunstan gold fields of Otago in the 1860s. Dunedin's Al-Huda mosque is the world's southernmost,[65] and the farthest from Mecca.[66]

Sport

A number of professional sports teams are based in the South Island — with the major spectator sports of rugby union and cricket particularly well represented. The Crusaders and Highlanders represent the upper and lower South Island respectively in rugby union's Super Rugby competition; and Canterbury, Otago, Southland Stags, Tasman Makos all participate in provincial rugby's ITM Cup. At cricket, the South Island is represented by the Canterbury Wizards, Central Stags, and Otago Volts in the Plunket Shield, one day domestic series, and the HRV Twenty20 Cup.

As well as rugby union and cricket, the South Island also boasts representative teams in the domestic basketball, soccer, ice hockey, netball, and rugby league.

The North vs South match, sometimes known as the Interisland match was a longstanding rugby union fixture in New Zealand. The first game was played in 1897 and the last match was played in 1995.

Christchurch also hosted the 1974 Commonwealth Games. An unidentified group is promoting a bid for the South Island to host the 2022 Winter Olympics.[67][68]

See also

- Cities and towns of the South Island by population

- List of twin towns and sister cities in the South Island

- Military of the South Island

- New Munster

- Nor'west arch

- South Island nationalism

References

- ^ "Quick Facts - Land and Environment : Geography - Physical Features". Statistics New Zealand. 2000. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- ^ King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Auckland: Penguin Books. pp. 280–281. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- ^ Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. p. 90. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- ^ "Moriori - The impact of new arrivals". Teara.govt.nz. 4 March 2009. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ a b c Tau, Te Maire. "Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand".

{{cite journal}}:|contribution=ignored (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bluff history - an overview (from the 'bluff.co.nz' website. Retrieved 14 December 2008.)

- ^ A.H. McLintock (ed), An Encyclopaedia of New Zealand”, 3 vols, Wellington, NZ:R.E. Owen, Government Printer, 1966, vol 3 p. 526.'

- ^ [1]

- ^ "The Ngai Tahu Report 1991".

- ^ Michael King (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- ^ Manying Ip. 'Chinese', Te Ara—the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, updated 21 December 2006, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/NewZealanders/NewZealandPeoples/Chinese/en

- ^ Strong quake hits near Christchurch, Radio New Zealand, 4 September 2010 (New Zealand Time)

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "New Zealand earthquake report – Sep 4 2010 at 4:35 am (NZST)". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ^ "New Zealand Quake Victims Say 'It was terrifying'". The Epoch Times. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ a b "New Zealand's South Island Rocked by Magnitude 7.0 Earthquake". Bloomberg. 3 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Latest News: Christchurch earthquake". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ "Central Christchurch to be evacuated after quake". Radio New Zealand. 4 September 2010. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Stuff.co.nz (4 September 2010). "Officers flown into protect Christchurch". Stuff. New Zealand. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ^ Published: 9:08 am Saturday 4 September 2010. "State of emergency declared after quake hits Chch | NATIONAL News". Tvnz.co.nz. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Massive 7.4 quake hits South Island", Stuff, New Zealand, 4 September 2010 (New Zealand Time)

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Canterbury shaken by 240 aftershocks". Stuff. New Zealand. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- ^ "Multiple fatalities in New Zealand earthquake near Christchurch". Daily Telegraph. UK. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ "New Zealand Earthquake Report – Feb 22, 2011 at 12:51 pm (NZDT)". GeoNet. Earthquake Commission and GNS Science. 22 February 2011. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- ^ Fox, Andrea (1 March 2011). "Building code no match for earthquake". The Dominion Post. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ "List of deceased". New Zealand Police. 1 June 2011. Retrieved 11 July 2011.

- ^ [2] Christchurch aftershocks: Hard-hit east residents three times unlucky

- ^ "Christchurch earthquake: Latest information - Friday". Stuff.co.nz. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ "'Thousands of homes need to go'". The Press. 14 June 2011. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ [3] Iconic cathedral window collapses in quake

- ^ [4] Anglican Taonga: Cathedral loses rose window

- ^ Davison, Isaac (22 April 2009). "North and South Islands officially nameless". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ^ "The Waitara Harbour Bill". Taranaki Herald. 30 July 1907. p. 4.

- ^ Guardian and Observer style guide: N ("New Zealand"), The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2012

- ^ Viewing Page 5997 of Issue 20687 Text of the 1846 Constitution from the [London Gazette]

- ^ Written submission in support of application for broadcasting funding, Richard Prosser, 18 April 2008

- ^ "Southern mayors plot united stand". Odt.co.nz. 13 October 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/PO1202/S00313/south-isl-strategic-alliance-faster-cheaper-collaborative.htm

- ^ Living Density: Table 1, Housing Statistics, Statistics New Zealand. Retrieved 25 January 2009. Areas are based on 2001 boundaries. Water bodies greater than 15 hectares are excluded.

- ^ "New Zealand Police Districts". Police.govt.nz. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Customs Service Offices - New Zealand". Customs.govt.nz. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Subnational Population Estimates: At 30 June 2019". Statistics New Zealand. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2020. For urban areas, "Subnational population estimates (UA, AU), by age and sex, at 30 June 1996, 2001, 2006–18 (2017 boundaries)". Statistics New Zealand. 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ Statistics New Zealand[dead link]

- ^ http://www.stats.govt.nz/~/media/Statistics/Browse%20for%20stats/SubnationalPopulationProjections/HOTP2031/SPP-06-31-tables.ashx

- ^ "Energy Data File". Ministry of Economic Development. 13 July 2011.

- ^ "MED Energy Sector Information: Waitaki River". MED. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- ^ "Home > Projects > Aviemore Dam". URS Corp. Retrieved 15 January 2009.

- ^ Published: 1:30PM Thursday 25 February 2010 (25 February 2010). "Origin in joint exploration venture in Canterbury Basin | BUSINESS News". Tvnz.co.nz. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Southland Energy Consortium". Energy.southlandnz.com. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ "Regional Gross Domestic Product". Statistics New Zealand. 2007. Retrieved 18 February 2010.

- ^ "South Island Index". Deloitte.com. 31 December 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2010.

- ^ About Hot Soup (5 November 2010). "Top Ten Tourist Attractions in New Zealand". Thequickten.com. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ Tony Hurst, Farewell to Steam: Four Decades of Change on New Zealand Railways (Auckland: HarperCollins, 1995), 96.

- ^ David Leitch, Steam, Steel and Splendour (Auckland: HarperCollins, 1994), 89.

- ^ "List of deceased – Christchurch earthquake". New Zealand Police. 7 April 2011. Retrieved 8 April 2011.

- ^ "Christchurch earthquake: Latest news - Wednesday". stuff.co.nz. 2 March 2011. Retrieved 2 March 2011.

- ^ From NIWA Science climate overview.

- ^ "Summary of New Zealand climate extremes". National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research. 2004. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Mean monthly sunshine hours" (XLS). National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research.

- ^ Hakatere Conservation Park, Department of Conservation website. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ^ Chinn, Trevor J.H., (1988), Glaciers of New Zealand, in Satellite image atlas of glaciers of the world, U.S. Geological Survey professional paper; 1386, ISBN 978-0-607-71457-9.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage official website listing".

- ^ "What are the populations served by DHBs? - FAQs about DHBs - Ministry of Health". Retrieved 11 May 2009.. Population based on Statistics New Zealand population projections in September 2007.

- ^ [5][dead link]

- ^ "New Zealand Flying Doctor Service". Airrescue.co.nz. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ "Muslim University Students' Association website". Otagomusa.wordpress.com. 28 May 2010. Retrieved 12 November 2010.

- ^ Distance between Mecca and Dunedin is 14,811.44 Kilometers according to http://www.geodatasource.com/distancecalculator.aspx

- ^ New Zealand Wants To Host A Winter Olympics

- ^ Greenhill, Marc (17 January 2011). "Winter Olympics bid 'ambitious'". The Press. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

External links

- South Island

- South Island Road Map

South Island travel guide from Wikivoyage

South Island travel guide from Wikivoyage