Warp drive

| Spatial anomalies in fiction |

|---|

|

Black holes in fiction • Portable hole • Teleportation in fiction • Wormholes in fiction • Stargate • Warp drive • Hyperspace • Time travel in fiction |

|

|

A warp drive or a drive enabling space warp is a fictional superluminal (faster than the speed of light) spacecraft propulsion system in many science fiction works, most notably Star Trek,[1] and a subject of ongoing physics research. The general concept of "warp drive" was introduced by John W. Campbell in his 1957 novel Islands of Space and was popularized by the Star Trek series. Its closest real-life equivalent is the Alcubierre drive, a theoretical solution of the field equations of general relativity.[2]

History and characteristics

[edit]Warp drive, or a drive enabling space warp, is one of several ways of travelling through space found in science fiction.[3] It has been often discussed as being conceptually similar to hyperspace.[3][4]: 238–239 A warp drive is a device that distorts the shape of the space-time continuum.[5]: 142 A spacecraft equipped with a warp drive may travel at speeds greater than that of light by many orders of magnitude. In contrast to some other fictitious faster-than-light technologies such as a jump drive, the warp drive does not permit instantaneous travel and transfers between two points, but rather involves a measurable passage of time which is pertinent to the concept. In contrast to hyperspace, spacecraft at warp velocity would continue to interact with objects in "normal space".[6][7]

The general concept of warp drive was introduced by John W. Campbell in his 1957 novel Islands of Space.[8][9]: 77 [10] Brave New Words gave the earliest example of the term "space-warp drive" as Fredric Brown's Gateway to Darkness (1949), and also cited an unnamed story from Cosmic Stories (May 1941) as using the word "warp" in the context of space travel, although the usage of this term as a "bend or curvature" in space which facilitates travel can be traced to several works as far back as the mid-1930s, for example Jack Williamson's The Cometeers (1936).[5]: 212, 268

Einstein's space warp and real-world physics

[edit]

Einstein's theory of special relativity states that speed of light travel is impossible for material objects that, unlike photons, have a non-zero rest mass. The problem of a material object exceeding light speed is that an infinite amount of kinetic energy would be required to travel at exactly the speed of light. Warp drives are one of the science-fiction tropes that serve to circumvent this limitation in fiction to facilitate stories set at galactic scales.[11] However, the concept of space warp has been criticized as "illogical", and has been connected to several other rubber science ideas that do not fit into our current understanding of physics, such as antigravity or negative mass.[3]

Some argue that these effects mean that although it's not possible to travel faster than the speed of light, both space and time "warp" to allow travelling the distance of one light year, in less than a year. Although it is not possible to travel faster than the speed of light, the effective speed is faster than light. This warping of space and time is precisely mathematically specified by the Lorentz factor, which depends on velocity. Although only theoretical when published over 100 years ago, the effect has since been measured and confirmed many times. In the limit, at light speed time stops completely (relative to a certain reference frame) and it is possible to travel infinite distances across space with no passage of time.[12][13][14][15]

Although the concept of warp drive has originated in fiction, it has received some scientific consideration, most notably related to the 1990s concept of the Alcubierre drive.[8] Alcubierre stated in an email to William Shatner that his theory was directly inspired by the term used in the TV series Star Trek[16] and cites the "'warp drive' of science fiction" in his 1994 article.[2]

In 2021, DARPA-funded researcher Harold White, of the Limitless Space Institute, claimed that he had succeeded in creating a real warp bubble, saying "our detailed numerical analysis of our custom Casimir cavities helped us identify a real and manufacturable nano/microstructure that is predicted to generate a negative vacuum energy density such that it would manifest a real nanoscale warp bubble, not an analog, but the real thing."[17]

Star Trek

[edit]

Warp drive is one of the fundamental features of the Star Trek franchise and one of the best-known examples of space warp (warp drive) in fiction.[3] In the first pilot episode of Star Trek: The Original Series, "The Cage", it is referred to as a "hyperdrive", with Captain Pike stating the speed to reach planet Talos IV as "time warp, factor 7". The warp drive in Star Trek is one of the most detailed fictional technologies.[18] Compared to the hyperspace drives of other fictional universes, it differs in that a spaceship does not leave the normal space-time continuum and instead the space-time itself is distorted, as is made possible in the general theory of relativity.[7]

The basic functional principle of the warp drive in Star Trek is the same for all spaceships. A strong energy source, usually a so-called warp core or sometimes called intermix chamber, generates a high-energy plasma. This plasma is transported to the so-called warp field generators via lines that are reminiscent of pipes. These generators are basically coils in warp nacelles protruding from the spaceship. These generate a subspace field, the so-called warp field or a warp bubble, which distort space-time and propels the bubble and spaceship in the bubble forward.[19]

The warp core can be designed in various forms. Humans and most of the other fictional races use a moderated reaction of antideuterium and deuterium. The energy produced passes through a matrix, which is made of a fictional chemical element, called dilithium. However, other species are shown to use different methods for faster-than-light propulsion. The Romulans, for example, use artificial micro-black holes called quantum singularities.[20]

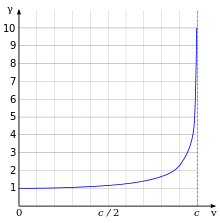

The speeds are given in warp factors and follow a geometric progression. The first scale developed by Franz Joseph was simply a cubic progression with no limit.[21] This leads to the use of ever growing warp factors in the Original Series and the Animated Series. For example, warp 14.1 in the TOS-episode "That Which Survives" or warp 36 in the TAS-episode "The Counter-Clock Incident". In order to focus more on the story and away from the technobabble, Gene Roddenberry commissioned Michael Okuda to invent a revised warp scale. Warp 10 should be the absolute limit and stand for infinite speed. In homage to Gene Roddenberry, this limit was also called "Eugene's Limit". Okuda explains this in an author's comment in his technical manual for the USS Enterprise-D.[22] Between Warp 1 (the speed of light) and Warp 9, the increase was still roughly geometric, but the exponent was adjusted so that the speeds were higher compared to the old scale. For instance, Warp 9 is more than 1500 times faster than Warp 1 in comparison to the 729 times (nine to the power of 3) calculated using the original cubic formula. In the same author's comment, Okuda explains that the motivation was to fulfill fan expectations that the new Enterprise is much faster than the original, but without changing the warp factor numbers.[22] Between Warp 9 and Warp 10, the new scale grows exponentially.[22] Only in a single episode of Star Trek Voyager there was a specific numerical speed value given for a warp factor. In the episode "The 37's", Tom Paris tells Amelia Earhart that Warp 9.9 is about 4 billion miles per second (using customary units for the character's benefit).[23] That is more than 14 times the value of Warp 9 and equal to around 21,400 times speed of light. However, this statement contradicts the technical manuals and encyclopedias written by Rick Sternbach and Michael Okuda, where a speed of 3053 times the speed of light was established for a warp factor of 9.9 and a speed of 7912 times the speed of light for a warp factor of 9.99. Both numerical values are well below the value given by Tom Paris.[24]

In the episode "Vis à Vis", a coaxial warp drive is mentioned. The working principle is explained in more detail in the Star Trek Encyclopedia. This variant of a warp drive uses spatial folding instead of a warp field and allows an instant movement with nearly infinite velocity.[25]

Star Trek has also introduced a so-called Transwarp concept, but without a fixed definition.[24] It is effectively a catch-all phrase for any and all technologies and natural phenomena that enable speeds above Warp 9.99.[26]

Rick Sternbach described the basic idea in the Technical Manual:

"Finally, we had to provide some loophole for various powerful aliens like Q, who have a knack for tossing the ship million of light years in the time of a commercial break. [...] This lets Q and his friends have fun in the 9.9999+ range, but also lets our ship travel slowly enough to keep the galaxy a big place, and meets the other criteria."[22]

See also

[edit]- Bussard collector

- Exotic matter

- Gravitational interaction of antimatter

- Krasnikov tube

- Negative energy

- Tachyons

- Timeline of black hole physics

- Timeline of gravitational physics and relativity

References

[edit]- ^ Krauss, Lawrence Maxwell. (2007). The physics of Star Trek. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-00863-6. OCLC 787849957.

- ^ a b Alcubierre, Miguel (1994). "The warp drive: Hyper-fast travel within general relativity". Classical and Quantum Gravity. 11 (5): L73–L77. arXiv:gr-qc/0009013. Bibcode:1994CQGra..11L..73A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/11/5/001. S2CID 4797900.

- ^ a b c d "SFE: Space Warp". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ Stableford, Brian M. (2006). Science Fact and Science Fiction: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ^ a b Prucher, Jeff (2007-05-07). Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988552-7.

- ^ Musha, Takaaki; Minami, Yoshinari (2011). Field Propulsion System for Space Travel: Physics of Non-Conventional Propulsion Methods for Interstellar Travel. Bentham eBooks. p. 58. ISBN 978-1-60805-270-7.

- ^ a b Miozzi, C. J. (18 June 2014). "5 Faster-Than-Light Travel Methods and Their Plausibility". The Escapist. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

- ^ a b Gardiner, J. (2008). "Warp Drive—From Imagination to Reality". Journal of the British Interplanetary Society. 61: 353–357. Bibcode:2008JBIS...61..353G.

- ^ Ash, Brian (1977). The Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-517-53174-7.

- ^ "Themes : Space Warp : SFE : Science Fiction Encyclopedia". www.sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-09-04.

- ^ "SFE: Faster Than Light". sf-encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2021-11-10.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (1905). "Zur Elektrodynamik bewegter Körper". Annalen der Physik. 322 (10): 891–921. Bibcode:1905AnP...322..891E. doi:10.1002/andp.19053221004.

- ^ Minkowski, Hermann (1908) [1907], [The Fundamental Equations for Electromagnetic Processes in Moving Bodies], Nachrichten von der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Mathematisch-Physikalische Klasse, pp. 53–111

- ^ Overbye, Dennis (2005-06-28). "A Trip Forward in Time. Your Travel Agent: Einstein". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- ^ Gott, Richard J. (2002). Time Travel in Einstein's Universe. p. 75.

- ^ Shapiro, Alan. "The Physics of Warp Drive". Archived from the original on 24 April 2013. Retrieved 2 June 2013.

- ^ Coontz, Lauren (December 9, 2021). "DARPA and NASA Scientists Accidentally Create Warp Bubble for Interstellar Travel". Coffee or Die Magazine. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ Dodds, Alice Rose (2022-06-10). "Star Trek's Warp Drive Technology, Explained". Game Rant. Retrieved 2023-01-19.

- ^ Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Technical Manual. p. 56.

- ^ Star Trek Fact Files, File 64, Card 6, Warp core function

- ^ Joseph, Franz. Star Trek: Star Fleet Technical Manual.

- ^ a b c d Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Technical Manual. p. 55.

- ^ "The Voyager Transcripts – The 37's". www.chakoteya.net. Retrieved 2024-05-27.

- ^ a b Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 413.

- ^ Okuda, Michael & Denise. Star Trek Encyclopedia. p. 149.

- ^ "Star Trek Fact Files". p. File 5, Card 19.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help)

External links

[edit]- Embedding of the Alcubierre Warp drive 2d plot in Google

- Warp drive at Memory Alpha

- Warp core at Memory Alpha

- Transwarp drive at Memory Alpha

- Quantum slipstream drive at Memory Alpha

- Warp Drive, When? A NASA feasibility article Archived 2008-07-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Special Relativity Simulator What would things look like at near-warp speeds?

- Alcubierre Warp Drive at the Encyclopedia of Astrobiology, Astronomy, and Spaceflight

- "Warp drive possible". BBC News. 1999-06-10. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- The Warp Drive Could Become Science Fact Archived 2012-11-23 at the Wayback Machine