Human rights in Russia: Difference between revisions

→External links: clean up |

|||

| Line 601: | Line 601: | ||

==LGBT rights== |

==LGBT rights== |

||

:''See [[LGBT rights in Russia]]'' |

:''See [[LGBT rights in Russia]]'' |

||

The author puts "far exceeding number of Russians were killed by immigrants" while there is no data on it. Moreover the term 'number of illegal immigrants' is broad, for instance all citizens from former Soviet Union do not require visa (except few) to be in Russia, therefore they can not be counted as illegal. |

|||

In general article greatly underestimates levels of racism in Russia. |

|||

==Psychiatric institutions== |

==Psychiatric institutions== |

||

Revision as of 12:18, 27 March 2008

|

|---|

The rights and liberties of the citizens of the Russian Federation are granted by Chapter 2 of the Constitution adopted in 1993.[1] Russia is a signatory to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and has also ratified a number of other international human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (fully) and the European Convention of Human Rights (with reservations). These international law instruments take precedence over national legislation according to Chapter 1, Article 15 of the Constitution.[1]

After his visits to the Russian Federation in 2004, Alvaro Gil-Robles, the first Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe, said that "the fledgling Russian democracy is still, of course, far from perfect, but its existence and its successes cannot be denied."[2]

In recent years Vladimir Lukin, current Ombudsman of the Russian Federation, has invariably characterized the human rights situation in Russia as unsatisfactory. However, according to Lukin, this is not discouraging, because building a lawful state and civil society in such a complex country as Russia is a hard and long process.[3]

However, Andrey Illarionov, former senior economic policy adviser to President Vladimir Putin, claimed in January 2007 that freedom in Russia has deteriorated dramatically since 2000 and that the year 2006 "was an extraordinary one in a sense of destruction of all types and all elements of freedom."[4]

Freedom House considered Russia partially free with scores of 5 on both political rights and civil liberties (1 being most free, 7 least free) in 2002-2004 and not free with 6 on political rights and 5 on civil liberties in 2005-2007 according to the Freedom in the World reports.[5] In 2006 The Economist published a democracy rating, putting Russia at 102nd place among 167 countries and defining it as a "hybrid regime with a trend towards curtailment of media and other civil liberties."[6] Russia occupies 120th place of 157 countries in the Index of Economic Freedom, composed by Heritage Foundation.[citation needed]

Andrey Illarionov claimed that the rule of law has ceased to exist in Russia and that litigants are now forced to apply not to the Russian courts, but to the European Court of Human Rights.[7] The court has indeed become overwhelmed with cases from Russia. As of June 12007, 22.5% of its pending cases were directed against the Russian Federation.[8] In 2006 there were 151 admissible applications against Russia (out of 1634 for all the countries), while in 2005 - 110 (of 1036), in 2004 - 64 (of 830), in 2003 - 15 (of 753), in 2002 - 12 (of 578).[9][10][11]

According to international human rights organizations as well as domestic press, violations of human rights in Russia[12] include widespread and systematic torture of persons in custody by police,[13][14] dedovshchina in Russian Army, neglect and cruelty in Russian orphanages,[15] violations of children's rights.[16] According to Amnesty International there is discrimination, racism, and murders of members of ethnic minorities.[17][18] Since 1992 at least 47 journalists have been killed.[19]

The situation in the Russian republic of Chechnya, ravaged by war, has been especially worrying. During the Second Chechen War, started in September 1999, there were summary executions and "disappearances" of civilians in Chechnya.[20][21][22] According to the ombudsman of the Chechen Republic, Nurdi Nukhazhiyev, as of March 2007 the most complex and painful problem is finding over 2700 abducted and forcefully held citizens; analysis of the complaints of citizens of Chechnya shows that social problems ever more often come to the foreground; two years ago complaints mostly concerned violations of the right to life.[23]

The Federal Law of 10 January2006 changed the orders affecting registration and operation of nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in Russia.[3][24][25] The Russian-Chechen Friendship Society was closed.[26]

There are cases of attacks on demonstrators organized by local authorities.[27] High concern was caused by murders of opposition lawmakers and journalists Anna Politkovskaya,[28] Yuri Schekochikhin,[29] Galina Starovoitova,[30] Sergei Yushenkov,[31] as well as imprisonments of human rights defenders, scientists, and journalists like Trepashkin,[32] Igor Sutyagin,[33] and Valentin Danilov.[34]

Judicial and penal system

The judiciary is a subject to manipulation by political authorities according to Amnesty International.[12][35] According to Constitution of Russia, top judges are [appointed] by the Federation Council, following nomination by the President of Russia.[36] Anna Politkovskaya described in her book Putin's Russia stories of judges who did not follow "orders from the above" and were assaulted or removed from their positions.[37] Former judge Olga Kudeshkina wrote an open letter in 2005 in which she criticized the chairman of the Moscow city court O. Egorova for "recommending judges to make right decisions" which allegedly caused more than 80 judges in Moscow to retire in the period from 2002 to 2005.[38]

In the 1990s, Russia's prison system was widely reported by media and human rights groups as troubled. There were large case backlogs and trial delays, resulting in lengthy pre-trial detention. Prison conditions were viewed as well below international standards.[citation needed] Tuberculosis was a serious, pervasive problem.[13] Human rights groups estimated that about 11,000 inmates and prison detainees die annually, most because of overcrowding, disease, and lack of medical care.[citation needed] A media report dated 2006 points to a campaign of prison reform that has resulted in apparent improvements in conditions.[39] The Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation has been working to reform Russia's prisons since 1997, in concert with reform efforts by the national government.[40]

The rule of law has made rather limited inroads in the criminal justice since the Soviet time, especially in the deep provinces.[41] The courts generally follow the non-acquittals policy; in 2004 acquittals constituted only 0.7 percent of all judgments. Judges are dependent on administrators, bidding prosecutorial offices in turn. The work of public prosecutors varies from poor to dismal. Lawyers are mostly court appointed and low paid. There was a rapid deterioration of the situation characterized by abuse of the criminal process, harassment and persecution of defense bar members in politically sensitive cases in recent years. The principles of adversariness and equality of the parties to criminal proceedings are not observed.[42]

In 1996, President Boris Yeltsin pronounced a moratorium on the death penalty in Russia. However, the Russian government still violates many promises it made upon entering the Council of Europe.[35] Citizens who appeal to European Court of Human Rights are often prosecuted by Russian authorities, according to the allegations of Politkovskaya[43]

Torture and abuse

The Constitution of Russia forbids arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment. Chapter2, Article 21 of the constitution states, "No one may be subjected to torture, violence or any other harsh or humiliating treatment or punishment."[44][45] However Russian police are regularly observed practicing torture - including beatings, electric shocks, rape, asphyxiation - in interrogating arrested suspects.[13][12][14] A popular method is called Phone Call to Putin.[13][14][46] In 2000, human rights Ombudsman Oleg Mironov estimated that 50% of prisoners with whom he spoke claimed to have been tortured. Amnesty International reported that Russian military forces in Chechnya rape and torture local women with electric shocks, when electric wires are connected to the straps of their bra on their chest.[44]

In the most extreme cases, hundreds of innocent people from the street were arbitrary arrested, beaten, tortured, and raped by special police forces. Such incidents took place not only in Chechnya, but also in Russian towns of Blagoveshensk, Bezetsk, Nefteyugansk, and others.[47][48][49]

On 2007 Radio Svoboda ("Radio Freedom", part of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty) reported that an unofficial movement "Russia the Beaten" was created in Moscow by human rights activists and journalists who "suffered from beatings in numerous Russian cities".[50] Torture and humiliation are also widespread in Russian army (see also dedovshchina).[51] Many young men are killed or commit suicide every year because of it.[52] It is reported that some young male conscripts are forced to work as prostitutes for "outside clients".[53] Union of the Committees of Soldiers' Mothers of Russia works to protect rights of young soldiers.

Crime

In the 1990s, the growth of organized crime (see Russian mafia and Russian oligarchs) and the fragmentation of law enforcement agencies in Russia coincided with a sharp rise in violence against business figures, administrative and state officials, and other public figures.[54] President Vladimir Putin inherited these problems when he took office, and during his election campaign in 2000, the new president won popular support by stressing the need to restore law and order and to bring the rule of law to Russia as the only way of restoring confidence in the country's economy.[55]

According to data by Demoscope Weekly, the Russian homicide rate showed a rise from the level of 15 murders per 100,000 people in 1991, to 32.5 in 1994. Then it fell to 22.5 in 1998, followed by a rise to a maximum rate of 30.5 in 2002, and then a fall to 20 murders per 100,000 people in 2006.[56][57]

With a prison population rate of 532 per 100,000 population, Russia is tied with Bermuda, the United Kingdom and Belarus and second only to the United States (2005 data).[58]

Criminology studies show that for the first five years since 2000 compared with the average for 1992 to 1999, the rate of robberies is up by 38.2% and the rate of drug-related crimes is higher by 71.7%.[59]

Politically-motivated prosecutions

Espionage cases

In Soviet period of time scientists encountered sufficient administrative barriers when working with foreign colleagues. After collapse of the Soviet Union which coincided with decrease of governmental financing, many scientists broadened their contacts with foreign laboratories. A point to note is that administrative norms of secrecy in Russia are still sufficiently more strict than those accepted in the West.[60]

There were several cases when FSB accused scientists for alleged transferring state secrets to different countries, while defendants and their colleagues claimed that transferred information or technologies were based on sources well known in the world. While such cases caused resonance in society, courts considering the cases were often closed from press.

Scientists in question are:

- Igor Sutyagin (sentenced to 15 years).[33]

- Physicist Valentin Danilov (sentenced to 14 years).[34]

- Physical chemist Oleg Korobeinichev (held under a written pledge not to leave city from 2006.[61] In May 2007 the case against him was closed by FSB for "absence of body of crime". In July 2007 prosecutors brought Korobeinichev public apologizes[62] for "the image of spy").

- Academician Oskar Kaibyshev (convicted to 6 years of suspended sentence and a fine of $130,000).[63][64]

Ecologist and journalist Alexander Nikitin, who worked with Bellona Foundation, was accused in espionage. He published material exposing hazards posed by the Russian Navy's nuclear fleet. He was acquitted in 1999 after spending several years in prison (his case was sent for re-investigation 13 times while he remained in prison). Other cases of prosecution are the cases of investigative journalist and ecologist Grigory Pasko, sentenced to three years imprisonment and later released under a general amnesty,[65][66] Vladimir Petrenko who described danger posed by military chemical warfare stockpiles and was held in pretrial confinement for seven months, and Nikolay Shchur, chairman of the Snezhinskiy Ecological Fund who was held in pretrial confinement for six months.[67]

Other cases

Viktor Orekhov, a former KGB captain who assisted Soviet dissidents and was sentenced to eight years of prison in Soviet time, in 1995 was sentenced for 3 years for unlawful store of weapons (which could be a fake[citation needed]). After one year he was released and left the country.[68]

Vil Mirzayanov was accused for 1992 article in which he has claimed that Russia was working on chemical WMD, but won the court, and later emigrated to U.S.[69]

Vladimir Kazantsev who disclosed illegal purchases of eavesdropping devices from foreign firms was arrested in August 1995, and released in the end of the year, however the case was not closed.[67][70] Investigator Mikhail Trepashkin was sentenced in May 2004 for 4 years of prison.[32]

Journalist Vladimir Rakhmankov in January 9, 2006 was sentenced for alleged defamation of the President in his article "Putin as phallic symbol of Russia" to fine of 20,000 roubles (about 695 USD).[71][72]

Political dissidents from the former Soviet republics, such as authoritarian Tajikistan and Uzbekistan, are often arrested by FSB and extradited to these countries for prosecution, despite protests from international human rights organizations.[73][74] Special services of Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Azerbaidjan also kidnap people at the Russian territory, with the implicit approval of FSB.[75]

Many people have been also illegally detained to prevent them from demonstrations during G8 Summit in 2006.[76]

Suspicious killings

Some Russian opposition lawmakers and investigative journalists are suspected to be assassinated while investigating corruption and alleged crimes conducted by state authorities or FSB: Sergei Yushenkov, Yuri Shchekochikhin, Alexander Litvinenko, Galina Starovoitova, Anna Politkovskaya, Paul Klebnikov.[29][31]

Situation in Chechnya

The Russian Government's policies in Chechnya are a cause for international concern.[21][22] It has been reported that Russian military forces have abducted, tortured, and killed numerous civilians in Chechnya,[77] but Chechen separatists have also committed abuses,[78] such as abducting people for ransom.[79] Human rights groups are very critical of cases of people disappearing in the custody of Russian officials. Systematic illegal arrests and torture conducted by the armed forces under the command of Ramzan Kadyrov and Federal Ministry of Interior have also been reported.[80] There are reports about repressions, information blockade, and atmosphere of fear and despair in Chechnya.[81]

As claimed in 2005 report by Memorial, there is a system of "conveyor of violence" in Chechen Republic (as well as in neighbouring Ingushetiya) when a person suspected in crimes connected with activity of separatists squads, is unlawfully detained by members of security agencies, and then disappears. After a while part of detainees is found in centers of preliminary detention (while some allegedly disappear forever), and then he is tortured to confess to a crime or/and to slander somebody else. According to Memorial, psychological pressure is also in use.[82] Known Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya compared this system with Gulag and claimed the number of several hundred cases.[83]

A number of journalists were killed in Chechnya or supposedly for reporting on the conflict.[19][84] List of names includes less and more famous: Cynthia Elbaum, Vladimir Zhitarenko, Nina Yefimova, Jochen Piest, Farkhad Kerimov, Natalya Alyakina, Shamkhan Kagirov, Viktor Pimenov, Nadezhda Chaikova, Supian Ependiyev, Ramzan Mezhidov and Shamil Gigayev, Vladimir Yatsina, Aleksandr Yefremov, Roddy Scott, Paul Klebnikov, Magomedzagid Varisov, and Anna Politkovskaya.[85]

Governmental organizations

Efforts to institutionalize official human rights bodies have been mixed. In 1996, human rights activist Sergey Kovalev resigned as chairman of the Presidential Human Rights Commission to protest the government's record, particularly the war in Chechnya. Parliament in 1997 passed a law establishing a "human rights ombudsman," a position that is provided for in Russia's constitution and is required of members of the Council of Europe, to which Russia was admitted in February 1996. The Duma finally selected Duma deputy Oleg Mironov in May 1998. A member of the Communist Party, Mironov resigned from both the Party and the Duma after the vote, citing the law's stipulation that the Ombudsman be nonpartisan. Because of his party affiliation, and because Mironov had no evident expertise in the field of human rights, his appointment was widely criticized at the time by human rights activists. International human rights groups operate freely in Russia, although the government has hindered the movements and access to information of some individuals investigating the war in Chechnya.[citation needed]

Some German politicians see things differently; Gerhard Schröder, the former German prime minister, explained to all the Western states that Putin is a "flawless democrat".[86]

Non-governmental organizations

The lower house of the Russian parliament passed a bill by 370-18 requiring local branches of foreign non-governmental organizations (NGOs) to re-register as Russian organizations subject to Russian jurisdiction, and thus stricter financial and legal restrictions. The bill gives Russian officials oversight of local finances and activities. The bill has been highly criticized by Human Rights Watch, Memorial organization, and the [INDEM Foundation] for its possible effects on international monitoring of the status of human rights in Russia.[87] In October 2006 the activities of many foreign non-governmental organizations were suspended using this law; officials said that "the suspensions resulted simply from the failure of private groups to meet the law's requirements, not from a political decision on the part of the state. The groups would be allowed to resume work once their registrations are completed."[25] Another crackdown followed in 2007.[88]

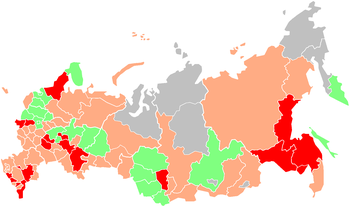

Green: Quite free

Orange: Not quite free

Red: unfree

Grey: No data (Free regions were not found)

Source: Glasnost Defense Foundation

Freedom of religion

The Constitution of Russian Federation provides for freedom of religion and the equality of all religions before the law as well as the separation of church and state. As Vladimir Lukin had stressed in his 2005 Ombudsman's report, "the Russian state has achieved significant progress in the observance of religious freedom and lawful activity of religious associations, overcoming a heritage of totalitarianism, domination of a single ideology and party dictatorship".[89]

Russia is a multi-ethnic country with a large majority of Orthodox Christians (61%), high proportion of Muslims (12%), 1% of Jews, about 1% of Catholics, and so on. According to Alvaro Gil-Robles, relations between the representatives of the different religious communities are generally harmonious.[2]

Gil-Robles emphasized the amount of state support provided by both federal and regional authorities for the different religious communities, and stressed the example of the Republic of Tatarstan as "veritable cultural and religious melting pot".[2] Along with that, Catholics are not always heeded as well as other religions by federal and local authorities.[2]

Vladimir Lukin noted in 2005, that citizens of Russia rarely experience violation of freedom of conscience (guaranteed by the article 28 of the Constitution).[89] So, the Commissioner's Office annually accepts from 200 to 250 complaints dealing with the violation of this right, usually from groups of worshipers, who represent various confessions: Orthodox (but not belonging to the Moscow patriarchy), Old-believers, Muslim, Protestant and others.[89]

The different problem arises with concern of citizens' right to association (article 30 of the Constitution).[89] As Vladimir Lukin noted, although quantity of the registered religious organizations constantly grows (22144 in 2005), an increasing number of religious organization fail to achieve legal recognition: e.g. Jehovah's Witnesses, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, and others.[89]

The influx of missionaries over the past several years has led to pressure by groups in Russia, specifically nationalists and the Russian Orthodox Church, to limit the activities of these "nontraditional" religious groups.[citation needed] In response, the Duma passed a new, restrictive, and potentially discriminatory law in October 1997. The law is very complex, with many ambiguous and contradictory provisions. The law's most controversial provisions separates religious "groups" and "organizations" and introduces a 15-year rule, which allows groups that have existed for 15 years or longer to obtain accredited status. According to Russian priest and dissident Gleb Yakunin, new religion law "heavily favors the Russian Orthodox Church at the expense of all other religions, including Judaism, Catholicism, and Protestantism.", and it is "a step backward in Russia's process of democratization".[90]

The claim to guarantee "the exclusion of any legal, administrative and fiscal discrimination against so-called non-traditional confessions" was adopted by PACE in June 2005.[91]

Anna Politkovskaya described cases of prosecution and even murders of Muslims by Russia's law enforcement bodies at the North Caucasus.[92][93] However, there are plenty of Muslims in higher government, Duma, and business.[94]

Press freedom

- See also Media freedom in Russia

Reporters Without Borders put Russia at 147th place in the World Press Freedom Index (from a list of 168 countries).[95] According to the Committee to Protect Journalists, 47 journalists have been killed in Russia for their professional activity, since 1992 (as of January 15, 2008). Thirty were killed during President Boris Yeltsin's reign, and the rest were killed under the current president Vladimir Putin.[19][96] According to the Glasnost Defence Foundation, there were 8 cases of suspicious deaths of journalists in 2007, as well as 75 assaults on journalists, and 11 attacks on editorial offices.[97] In 2006, the figures were 9 deaths, 69 assaults, and 12 attacks on offices.[98] In 2005, the list of all cases included 7 deaths, 63 assaults, 12 attacks on editorial offices, 23 incidents of censorship, 42 criminal prosecutions, 11 illegal layoffs, 47 cases of detention by militsiya, 382 lawsuits, 233 cases of obstruction, 23 closings of editorial offices, 10 evictions, 28 confiscations of printed production, 23 cases of stopping broadcasting, 38 refusals to distribute or print production, 25 acts of intimidation, and 344 other violations of Russian journalist's rights.[99]

Russian journalist Anna Politkovskaya, famous for her criticisms of Russia's actions in Chechnya, and the pro-Kremlin Chechya government, was assassinated in Moscow. Former KGB officer Oleg Gordievsky believes that the murders of writers Yuri Shchekochikhin (author of Slaves of KGB), Anna Politkovskaya, and Aleksander Litvinenko show that the FSB has returned to the practice of political assassinations,[100] practised in the past by the Thirteenth KGB Department.[101]

Opposition journalist Yevgenia Albats in interview with Eduard Steiner has claimed: "Today the directors of the television channels and the newspapers are invited every Thursday into the Kremlin office of the deputy head of administration, Vladislav Surkov to learn what news should be presented, and where. Journalists are bought with enormous salaries."[86]

Freedom of assembly

National minorities

Russian Federation is a multi-national state with over 170 ehtnic groups designated as nationalities, population of these groups varying enormously, from millions in case of e.g. Russians and Tatars to under ten thousand in the case of Nenets and Samis.[2] Among 85 subjects which constitute the Russian Federation, there are 21 national republics (meant to be home to a specific ethnic minority), 5 autonomous okrugs (usually with substantial or predominant ethnic minority) and an autonomous oblast. However, as Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe Gil-Robles noted in 2004 report, whether or not the region in "national", all the citizens have equal rights and no one is privileged or discriminated on account of their ethnic affiliation.[2]

As Gil-Robles noted, although co-operation and good relations are still generally the rule in most of regions, tensions do arise, whose origins vary. Their sources include problems related to peoples that suffered Stalinists repressions, social and economic problems provoking tensions between different communities, and the situation in Chechnya and the associated terrorist attacks with resulting hostility towards people from the Caucasus and Central Asia, which takes the form of discrimination and overt racism towards the groups in question.[2]

Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe[102] in May 2007 issued concern that Russia still hasn't adopted comprehensive anti-discrimination legislation, and the existing anti-discrimination provisions are seldom used in spite of reported cases of discrimination.[103]

As Gil-Robles has noted in 2004, minorities are generally represented on local and regional authorities, and participate actively in public affairs. Gil-Robles emphasized the degree of co-operation and understanding between the various nationalities living in the same area, as well as the role of regional and local authorities in ethnic dialogue and development.[2] Along with that, Committee of Ministers in 2007 noted certain setbacks in minority participation in public life, including the abrogation of federal provisions for quotas for indigenous people in regional legislatures.[103]

Although the Constitution of the Russian Federation recognises Russian as the official language, the individual republics may declare one or more official languages. Most of subjects have at least two — Russian and the language of the "eponymous" nationality.[2] As Ministers noted in 2007, there is a lively minority language scene in most subjects of the federation, with more than 1,350 newspapers and magazines, 300 TV channels and 250 radio stations in over 50 minority languages. Moreover, new legislation allows usage of minority languages in federal radio and TV broadcasting.[103]

In 2007, there were 6,260 schools which provided teaching in altogether 38 minority languages, and over 75 minority languages were taught as a discipline in 10,404 schools. Ministers of Council of Europe has noted efforts to improve the supply of minority language textbooks and teachers, as well as greater availability of minority language teaching. However, as Ministers has noted, there remain shortcomings in the access to education of persons belonging to certain minorities.[103]

There are more than 2,000 national minorities' public assotiations and 560 national cultural autonomies, however the Committee of Ministers has noted that in many regions amount of state support for the preservation and development of minority cultures is still inadequate.[103] Alvaro Gil-Robles noted in 2004, that there's a significant difference between "eponymous" ethnic groups and nationalities without their own national territory, as resources of the last are relatively limited.[2]

Russia is also home of a particular category of minority peoples, i.e. small indigenous peoples of the North and Far East, who maintain very traditional lifestyles, often in a hazardous climatic environment, while adapting to the modern world.[2] After the fall of the Soviet Union Russian Federation passed legislation to protect rights of small northern indigenous peoples.[2] Gil-Robles has noted agreements between indigenous representatives and oil companies, which are to compensate potential damages on peoples habitats due to oil exploration.[2] As Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe noted in 2007, despite some initiatives for development, the social and economic situation of numerically small indigenous peoples was affected by recent legislative amendments at the federal level, removing some positive measures as regards their access to land and other natural resources.[103]

Alvaro Gil-Robles noted in 2004, that like many European countries, Russian Federation is also host to many foreigners, who when concentrated in a particular area make up so-called new minorities, who experience troubles e.g. with medical treatment due to absence of registration. Those who are registered encounter other integration problems because of language barriers.[2]

Committee of Ministers has noted in 2007 that despite efforts to improve access to residency registration and citizenship for national minorities, still those measures haven't regularised the situation of all the persons concerned.[103]

Foreigners and migrants

On October 2002 the Russian Federation has introduced new legislation on legal rights of foreigners, designed to control immigration and clarify foreigners' rights. Despite this legal achievement, as of 2004, numerous foreign communities in Russia faced difficulties in practice (according to Alvaro Gil-Robles).[2]

Most of foreigners arriving in Russia are seeking for job. In many cases they have no preliminary contracts or other agreements with a local employer. A typical problem is the illegal status of many foreigners (i.e., they are not registered and have no identity papers), what deprives them of any social assistance (as of 2004) and often leads to their exploitation by the employer. Despite that, foreigner workers still benefit, what with seeming reluctance of regional authorities to solve the problem forms a sort of modus vivendi.[2] As Gil-Robles noted, it's easy to imagine that illegal status of many foreigners creates grounds for corruption. Illegal immigrants, even if they have spent several years in Russia may be arrested at any moment and placed in detention centres for illegal immigrants for further expulsion. As of 2004, living conditions in detention centers are very bad, and expulsion process lacks of funding, what may extend detention of immigrants for months or even years.[2] Along with that, Gil-Robles detected a firm political commitment to find a satisfactory solution among authorities he spoke with.[2]

There's a special case of former Soviet citizens. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, 1991 Nationality Law recognised all former Soviet citizens permanently resident in the Russian Federation as Russian citizens. However, people born in Russia who weren't on the Russian territory when the law came into force, as well as some people born in the Soviet Union who lived in Russia but weren't formally domiciled there weren't granted Russian citizenship. When at December 31, 2003 former Soviet passports became invalid, those people overnight become foreigners, although many of them considered Russia their home. The majority were even deprived of retirement benefits and medical assistance. Their morale has also been seriously affected since they feel rejected.[2]

Another special case are Meskhetian Turks. Victims of both Stalin deportation from South Georgia and 1989 pogroms in the Fergana valley in Uzbekistan, some of them were eventually dispersed in Russia. While in most regions of Russia Meskhetian Turks were automatically granted Russian citizenship, in Krasnodar Krai some 15,000 Meskhetian Turks were deprived of any legal status since 1991.[2] Unfortunately, even measures taken by Alvaro Gil-Robles in 2004 didn't make Krasnodar authorities to change their position; Vladimir Lukin in the 2005 report called it "campaign initiated by local authorities against certain ethnic groups".[89] The way out for a significant number of Meskhetian Turks in the Krasnodar Krai became resettlement in the United States.[104] As Vladimir Lukin noted in 2005, there was similar problem with 5.5 thousand Yazidis who before the disintegration of the USSR moved to the Krasnodar Krai from Armenia. Only one thousand of them were granted citizenship, the others could not be legalized.[89]

In 2006 Russian Federation after initiative proposed by Vladimir Putin adopted legislation which in order to "protect interests of native population of Russia" provided significant restrictions on presence of foreigners on Russian wholesale and retail markets.[105]

There was a short campaign of frequently arbitrary and illegal detention and expulsion of ethnic Georgians on charges of visa violations and a crackdown on Georgian-owned or Georgian-themed businesses and organizations in 2006, as a part of 2006 Georgian-Russian espionage controversy.[106]

Newsweek reported that "[In 2005] some 300,000 people were fined for immigration violations in Moscow alone. [In 2006], according to Civil Assistance, numbers are many times higher."[107]

Racism and xenophobia

As Alvaro Gil-Robles noted in 2004, the main communities targeted by xenophobia are the Jewish community, groups originating from the Caucasus, migrants and foreigners, and sexual minorities.[2]

In his 2006 report, Vladimir Lukin has noted rise of nationalistic and xenophobic sentiments in Russia, as well as more frequent cases of violence and mass riots on the grounds of racial, nationalistic or religious intolerance.[3][18][108]

There are 15 million illegal immigrants living in Russia.[citation needed] Human rights activists point out that 44 people were murdered and close to 500 assaulted on racial grounds in 2006,[109] while a far exceeding number of Russians attacked and killed by immigrants is not even mentioned in any official reports.[citation needed] According to official sources, there are 150 "extremist groups" with over 5000 members in Russia.[110]

The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe has noted in 2007, that high-level representatives of the federal administration have publicly endorsed the fight against racism and intolerance, and a number of programmes have been adopted to implement these objectives. This has been accompanied by an increase in the number of convictions aimed at inciting national, racial or religious hatred. However, there has been an alarming increase in the number of racially motivated violent assaults in the Russian Federation in four years, yet many law enforcement officials still often appear reluctant to acknowledge racial or nationalist motivation in these crimes. Hate speech has become more common in the media and in political discourse. The situation of persons originating in the Northern Caucasus is particularly disturbing.[103]

Vladimir Lukin noted that inactivity of the law enforcement bodies may cause severe consequences, like September 2006 inter-ethnic riot in town Kondopoga of the Republic of Karelia. Lukin noted provocative role of the so-called Movement Against Illegal Immigration. As the result of the Kondopoga events, all heads of the "enforcement bloc" of the republic were fired from their positions, several criminal cases were opened.[3]

According to nationwide opinion poll carried by VCIOM in 2006, 44% of respondents consider Russia "a common house of many nations" where all must have equal rights, 36% think that "Russians should have more rights since they constitute the majority of the population", 15% think "Russia must be the state of Russian people". However the question is also what exactly does the term "Russian" denote. For 39% of respondents Russians are all who grew and were brought up in Russia's traditions; for 23% Russians are those who works for the good of Russia; 15% respondents think that only Russians by blood may be called Russians; for 12% Russians are all for who Russian language is native, for 7% Russians are adepts of Russian Christian Orthodox tradition.[111]

LGBT rights

The author puts "far exceeding number of Russians were killed by immigrants" while there is no data on it. Moreover the term 'number of illegal immigrants' is broad, for instance all citizens from former Soviet Union do not require visa (except few) to be in Russia, therefore they can not be counted as illegal.

In general article greatly underestimates levels of racism in Russia.

Psychiatric institutions

There are numerous cases when people "inconvenient" for Russian authorities are imprisoned in psychiatric institutions during the last years.[112][113][114][115]

Little has changed in the Moscow Serbsky Institute where many prominent Soviet dissidents had been incarcerated after having been diagnosed with sluggishly progressing schizophrenia. This Institute conducts more than 2,500 court-ordered evaluations per year. When war criminal Yuri Budanov was tested there in 2002, the panel conducting the inquiry was led by Tamara Pechernikova, who had condemned the poet Natalya Gorbanevskaya in the past. Budanov was found not guilty by reason of "temporary insanity". After public outrage, he was found sane by another panel that included Georgi Morozov, the former Serbsky director who had declared many dissidents insane in the 1970s and 1980s.[116] Serbsky Institute also made an expertise of mass poisoning of hundreds of Chechen school children by an unknown chemical substance of strong and prolonged action, which rendered them completely incapable for many months.[117] The panel found that the disease was caused simply by "psycho-emotional tension".[118][119]

Disabled and children's rights

Currently, the estimated orphan population in Russia is 2 million and the street children is 4 million.[120] According to an earlier Human Rights Watch report in 1998,[15] "Russian children are abandoned to the state at a rate of 113,000 a year for the past two years, up dramatically from 67,286 in 1992." "Of a total of more than 600,000 children classified as being “without parental care,” as many as one-third reside in institutions, while the rest are placed with a variety of guardians." "From the moment the state assumes their care, orphans in Russia—of whom 95 percent still have a living parent—are exposed to shocking levels of cruelty and neglect." Once officially labelled as retarded, Russian orphans are "warehoused for life in psychoneurological internaty. In addition to receiving little to no education in such internaty, these orphans may be restrained in cloth sacks, tethered by a limb to furniture, denied stimulation, and sometimes left to lie half-naked in their own filth. Bedridden children aged five to seventeen are confined to understaffed lying-down rooms as in the baby houses, and in some cases are neglected to the point of death." Life and death of disabled children in the State institutions was described by writer Ruben Galiego.[121][122] Still, the recent adoption law made it more difficult to adopt Russian children from abroad.

Human trafficking

The end of communism and collapse of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia has contributed to an increase in human trafficking, with the majority of victims being women forced into prostitution.[123][124] Russia is a country of origin for persons, primarily women and children, trafficked for the purpose of sexual exploitation. Russia is also a destination and transit country for persons trafficked for sexual and labour exploitation from regional and neighbouring countries into Russia and beyond. Russia accounted for one-quarter of the 1,235 identified victims reported in 2003 trafficked to Germany. The Russian government has shown some commitment to combat trafficking but has been criticised for failing to develop effective measures in law enforcement and victim protection.[125][126]

References

- ^ a b

The Constitution of the Russian Federation (in English translation). Washington, D.C.: Embassy of the Russian Federation. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u "Report by Mr. Alvaro Gil-Robles on his Visits to the Russian Federation". Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights. 2005-04-20. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b c d Lukin, Vladimir (2007). "The Report of the Commissioner for Human Rights in the Russian Federation for the Year 2006" (MS Word). Retrieved 2008-03-16. Russian language version.

- ^ Freedom in the World 2007: Is Freedom Under Threat? Peter Ackerman, Andrei Illarionov, Jennifer L. Windsor, Joanne J. Myers, January 302007.

- ^ Freedom in the World: The Annual Survey of Political Rights and Civil Liberties.

- ^ Index of democracy by Economist Intelligence Unit

- ^ Freedom in the World 2007: Is Freedom Under Threat? Peter Ackerman, Andrei Illarionov, Jennifer L. Windsor, Joanne J. Myers, January 302007.

- ^ ECHR. Pending cases. 01.06.2007

- ^ ECHR. Survey of activities. 2006

- ^ ECHR. Survey of activities. 2004

- ^ ECHR. Survey of activities. 2005

- ^ a b c Rough Justice: The law and human rights in the Russian Federation (PDF). Amnesty International. 2003. ISBN 0-86210-338-X. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b c d "Torture and ill-treatment". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b c UN Committee against Torture Must Get Commitments From Russia to Stop Torture

- ^ a b Cruelty and neglect in Russian orphanages

- ^ "Children's rights". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Ethnic minorities under attack". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b 'Dokumenty!': Discrimination on grounds of race in the Russian Federation (PDF). Amnesty International. 2003. ISBN 0-86210-322-3. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b c "Journalists killed: Statisistics and Background". Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved 2008-03-16. (As of January 15, 2008).

- ^ Russia Condemned for Chechnya Killings

- ^ a b "Chechnya – human rights under attack". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b Russia Condemned for 'Disappearance' of Chechen

- ^ Interview with Nurdi Nukhazhiyev by Khamzat Chitigov for Strana.Ru.

- ^ Russia's NGOs: It's not so simple by N. K. Gvozdev

- ^ a b Finn, Peter (2006-10-19). "Russia Halts Activities of Many Groups From Abroad". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Court Orders Closure of Russian-Chechen Friendship Society

- ^ Supporters of Anna Politkovskaia Attacked at Ingushetia Demonstration

- ^ "Chechen war reporter found dead". BBC News. 2006-10-07. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b "Agent unknown". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). 2006-10-30. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Amnesty International condemns the political murder of Russian human rights advocate Galina Starovoitova". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b "Yushenkov: A Russian idealist". BBC News. 2003-04-17. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b "Trepashkin case". Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b "Case study: Igor Sutiagin". Human Rights Situation in Chechnya. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b "Physicist Found Guilty". AAAS Human Rights Action Network. American Association for the Advancement of Science. 2004-11-12. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b The Russian Federation: Denial of Justice (PDF). Amnesty International. 2002. ISBN 0-86210-318-5. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^

"Chapter 7. Judiciary, Article 128". The Constitution of the Russian Federation (in English translation). Democracy.Ru.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ Politkovskaya, Anna (2004) Putin's Russia

- ^ Kudeshkina, Olga (2005-03-09). "Open letter to President Putin". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ After the Gulag: conjugal visits, computers...and a hint of violence - Times Online

- ^ SDC in Russia - Prison Reform Project

- ^ Pomorski, Stanislaw (2001) Justice in Siberia: a case study of a lower criminal court in the city of Krasnoyarsk. Communist and Post-Communist Studies 34.4, 447-478.

- ^ Pomorski, Stanislaw (2006). Modern Russian criminal procedure: The adversarial principle and guilty plea. Criminal Law Forum 17.2, 129-148.

- ^ Politkovskaya, Anna (2006-06-29). "It is forbidden even to speak about the Strasbourg Court". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b "Russian Federation Preliminary briefing to the UN Committee against Torture". Amnesty International. 2006-04-01. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^

"Chapter 2. Judiciary, Article 21". The Constitution of the Russian Federation (in English translation). Democracy.Ru.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: unrecognized language (link) - ^ "Torture in Russia". Amnesty International. 1997-04-03. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Hayrullin, Marat (2005-01-10). "The entire city was beaten". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Hayrullin, Marat (2005-03-17). "A profession: to mop up the Motherland". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Hayrullin, Marat (2005-04-25). "Welcome to Fairytale". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "«Россия избитая» требует отставки министра внутренних дел" (in Russian). Radio Svoboda. 2005-07-30. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ The Consequences of Dedovshchina, Human Rights Watch report, 2004

- ^ Ismailov, Vjacheslav (2005-04-25). "Terrible Dedovshchina in General Staff". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Conscript's Prostitution Claims Shed Light On Hazing Radio Free Europe March 21, 2007

- ^ Tanya Frisby, "The Rise of Organised Crime in Russia: Its Roots and Social Significance," Europe-Asia Studies, 50, 1, 1998, p. 35.

- ^ Peterson, Scott (2004-03-12). "A vote for democracy, Putin-style". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Russian demographic barometer by Ekaterina Shcherbakova at Demoscope Weekly, issue of 19 March - 7 April 2007.

- ^ World statistics of murders per capita, by NationMaster.Com

- ^ World Prison Population List 2005

- ^ Big Costs and Little Security - by Vladislav Inozemtsev, Moscow Times, December 22, 2006.

- ^

Alexei Napylov. "Утраченные секреты горения". Lenta.Ru (in Russian). Rambler. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

According to 'Independent military survey', in the U.S. only 2-3% of scientific information considering national defence is secret, while in Russia only 2-3% of that is not secret.

- ^ Russian Scientist Charged With Disclosing State Secret

- ^ Prosecutors of Novosibirsk refused to make public apologies to the scientist, July 2007, computer translation from Russian

- ^ Oskar Kaibyshev convicted

- ^ Science Fiction News, September 2006

- ^ Grigory Pasko site

- ^ The Pasko case

- ^ a b Counterintelligence Cases- by GlobalSecurity.org

- ^ Service, part III by V. Voronov (in Russian)

- ^ Details of national counterintelligence (in Russian) by Vladimir Voronov.

- ^ Researchers Throw Up Their Arms

- ^ News of site cursiv.ru (in Russian)

- ^ Russia: 'Phallic' Case Threatens Internet Freedom

- ^ Borogan, Irina (2006-10-07). "ЧАЙКА ЗАЛЕТИТ В ЕВРОПЕЙСКИЙ СУД?". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Podrabinek, Aleksander (2006-10-30). "FSB serves to Islam". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Soldatov, Andrei (2006-02-27). "Special services of former Soviet republics at the Russian territory". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Andreevav, Nadezda (2006-07-20). "Surveying all oppositioners in the city of Saratov". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Abuses by Russian forces". Human Rights Situation in Chechnya. Human Rights Watch. 2003-04-07. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Abuses by Chechen forces". Human Rights Situation in Chechnya. Human Rights Watch. 2003-04-07. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Five people abducted in Chechnya

- ^ "Widespread Torture in the Chechen Republic". Human Rights Watch. 2006-11-13. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Neistat, Anna (2006-07-06). "Diary". London Review of Books. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Fabrication of criminal cases (at example of the case of Vladovskikh), chapter of 2005 report by Memorial.

- ^ Stalinism Forever - by Anna Politkovskaya - The Washington Post

- ^ Today In The UK - Journalists killed in Chechnya

- ^ Hearst, David (2006-10-09). "Obituary: Anna Politkovskaya". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b

Albaz, Jewgenija (2007-04). "What should I be afraid of?". Kontakt. Erste Bank Group. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Myers, Steven Lee (2005-11-23). "Russia Moves to Increase Control Over Charities and Other Groups". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Gee, Alastair (2007-08-22). "Crackdown on NGOs pushes 600 charities out of Russia". The Independent. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lukin, Vladimir (2006). "The Report of the Commissioner for Human Rights in the Russian Federation for the Year 2005" (MS Word). Retrieved 2008-03-16. Russian language version.

- ^ "Father Gleb Yakunin: Religion Law Is a Step Backward for Russia". FSUMonitor. Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Resolution 1455 of PACE, June 2005.

- ^ Politkovskaya, Anna (2005-03-14). "One can pray. But not too often". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Politkovskaya, Anna (2006-07-10). "A man who was killed 'just in case'". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ www.kremlin.ru, www.gov.ru, www.rspp.ru

- ^ Worldwide Press Freedom Index 2006

- ^

"Russia". Attacks on the Press in 2007. Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

Fourteen journalists have been slain in direct relation to their work during Putin's tenure, making Russia the world's third-deadliest nation for the press.

- ^ "Digest No. 363". Glasnost Defense Foundation. 2007-12-27. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Digest No. 312". Glasnost Defense Foundation. 2007-01-09. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Digest No. 261". Glasnost Defense Foundation. 2006-01-10. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Бывший резидент КГБ Олег Гордиевский не сомневается в причастности к отравлению Литвиненко российских спецслужб" (in Russian). Radio Svoboda. 2006-11-20. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Christopher Andrew, Vasili Mitrokhin, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB in Europe and the West, Gardners Books (2000), ISBN 0-14-028487-7

- ^ The Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe builds its work in Russia on the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, European document, ratified by Russia in 1998.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Resolution on the implementation of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, Committee of Ministers of Council of Europe, May 2, 2007

- ^ Meskhetian Turk resettlement: the view from Krasnodar Krai, September 19, 2005

- ^ Putin, Vladimir (2006-10-05). "Opening Address at the Session of the Council for the Implementation of Priority National Projects and Demographic Policy". President of Russia. Archived from the original on 2006-10-12.

I charge the heads of the regions of the Russian Federation to take additional measures to improve trade in the wholesale and retail markets with a view to protect the interests of Russian producers and population, the native Russian population.

Russian language version. - ^ Russia Targets Georgians for Expulsion. The Human Rights Watch. October 1, 2007.

- ^

Matthews, Owen (2006-11-06). "State of Hate". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Xenophobia in Russia Becoming Dangerously Common

- ^ "Год нетерпимости: 500 пострадавших, 44 убитых" (in Russian). Radio Svoboda. 2006-12-26. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Russian Federation: Racism and xenophobia rife in Russian society". Amnesty International. 2006-05-04. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Russia for Russians or for all?" (in Russian), press release by VCIOM

- ^ Adrian Blomfield (2007-08-14). "Labelled mad for daring to criticise the Kremlin". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ Speak Out? Are You Crazy? - by Kim Murphy, Los Angeles Times, May 30, 2006

- ^ In Russia, Psychiatry Is Again a Tool Against Dissent - by Peter Finn, Washington Post, September 30, 2006

- ^ Psychiatry used as a tool against dissent - by Association of American Physicians and Surgeons, October 2, 2006

- ^ Psychiatry’s painful past resurfaces - from Washington Post 2002

- ^ Litvinovich, Marina (2006-12-04). "A mysterious illness moves along the roads and makes frequent stops in schools". Novaya Gazeta (in Russian). Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ What made Chechen schoolchildren ill? - The Jamestown Foundation, March 30, 2006

- ^ War-related stress suspected in sick Chechen girls - by Kim Murphy, Los Angeles Times, March 19, 2006

- ^ Children of Russia - abused, abandoned, forgotten - report by Le Journal Chretien

- ^ Ruben Galliego and Marian Schwartz (Translator) White on Black Harcourt 2006 ISBN 0-15-101227-X

- ^ Ruben Galliego wins Booker Russia Prize.

- ^ "Trafficking in human beings". Council of Europe. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "A modern slave's brutal odyssey". BBC News. 2004-11-03. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Trafficking in Persons Report". U.S. Department of State. 2005-06-03. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

- ^ "Russia". The Factbook on Global Sexual Exploitation. Coalition Against Trafficking of Women. Retrieved 2008-03-16.

See also

- Human rights in the Soviet Union

- Human rights in Europe

- Politics of Russia

- International Helsinki Federation for Human Rights

- Moscow Helsinki Group

- International human rights instruments

External links

- Report 2007: Russian Federation - report by Amnesty International.

- Commissioner for Human Rights of the Russian Federation - Office of Ombudsman Vladimir Lukin. English translations of some reports are in the index.

- Report by Mr. Alvaro Gil-Robles on his Visits to the Russian Federation - Published by the Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights, 2005-04-20.

- OHCHR: Russian Federation - from the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights

- U.N. Team in the Russian Federation

- Statement by U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights - the statement of Louise Arbour after her visit to Russia, including Chechnya, 2006-02-24.

- Committee Against Torture - in Nizhny Novgorod.

- Human Rights Watch: Russia

- Human Rights Watch: Positively Abandoned - Discrimination against HIV-Positive Mothers and their Children, June 2005.

- HIV/AIDS and Human Rights in Russia - U.N. Chronicle, 2006.

- IFEX: Russia - from the International Freedom of Expression Exchange.

- IPI Watch List: Russia - from the International Press Institute.

- FSUMonitor.com - published by the Union of Councils for Jews in the Former Soviet Union.

- RFE/RL: Russia Report - published by Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

- Human Rights Country Reports - published by the U.S. Department of State

- International Religious Freedom Reports - published by the U.S. Department of State

- Human Rights Violations in Chechnya - last updated in 2006.

- Human Rights in Russia - links.

Further reading

- Emma Gilligan. Defending human rights in Russia: Sergei Kovalyov, dissident and human rights commissioner, 1969-2003. RoutledgeCurzon. 2004. ISBN 0-415-32369-X.

- Pamela A. Jordan. Defending Rights in Russia: Lawyers, the State, And Legal Reform in the Post-Soviet Era. University of British Columbia Press. 2006. ISBN 0-7748-1163-3.

- Andrew Meier. Black Earth: A Journey through Russia After the Fall. Norton. 2005. ISBN 0-393-32641-1.

- Anna Politkovskaya. Putin's Russia. Harvill. 2004. ISBN 0-805-07930-0.

- Archana Pyati. The New Dissidents: Human Rights Defenders and Counterterrorism in Russia. Human Rights First. 2005. ISBN 0-9753150-0-5. About the author.

- David Satter. Darkness at Dawn: The Rise of the Russian Criminal State. Yale University Press. 2003. ISBN 0-300-09892-8.

- Jonathan Weiler. Human Rights in Russia: A Darker Side of Reform. Lynne Rienner Publishers 2004. ISBN 1-58826-279-0.

FSB, terror

- Yevgenia Albats. The State Within a State: The KGB and its Hold on Russia - Past, Present, and Future. Farrar Straus Giroux. 1994. ISBN 0-374-18104-7.

- Yuri Felshtinsky and Alexander Litvinenko. Blowing up Russia: Terror from within. S.P.I. Books. 2002. ISBN 1-56171-938-2.

Chechnya

- Khassan Baiev and Ruth Daniloff. The Oath: A Surgeon Under Fire. Walker. 2004. ISBN 0-8027-1404-8.

- Anna Politkovskaya. A Dirty War: A Russian reporter in Chechnya. Harvill. 2001. ISBN 1-860-46897-7.

- Anna Politkovskaya. A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya. University of Chicago Press. 2003. ISBN 0-226-67432-0.