Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia

| Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia, Christ-Siemens-Touraine syndrome[1]: 570 |

| |

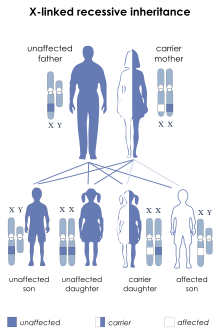

| This condition is inherited in an X-linked recessive manner. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is one of about 150 types of ectodermal dysplasia in humans. These disorders result in the development of structures including the skin where people sweat less.[2]

Presentation

[edit]

Most people with hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia have a reduced ability to sweat (hypohidrosis) because they have fewer sweat glands than normal or their sweat glands do not function properly. Sweating is a major way that the body controls its temperature; as sweat evaporates from the skin, it cools the body.

The hair is often light-coloured, brittle, and slow-growing. This condition is also characterized by absent teeth (hypodontia) or teeth that are malformed.

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia is the most common form of ectodermal dysplasia in humans. It is estimated to affect at least 1 in 17,000 people worldwide.[citation needed]

Genetics

[edit]Mutations in the EDA, EDAR, and EDARADD genes cause hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia. The EDA, EDAR, and EDARADD genes provide instructions for making proteins that work together during embryonic development. These proteins form part of a signaling pathway that is critical for the interaction between two cell layers, the ectoderm and the mesoderm. In the early embryo, these cell layers form the basis for many of the body's organs and tissues. Ectoderm-mesoderm interactions are essential for the formation of several structures that arise from the ectoderm, including the skin, hair, nails, teeth, and sweat glands.[citation needed]

Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia has several different inheritance patterns.

EDA (X-linked)

[edit]Most cases are caused by mutations in the EDA gene, which are inherited in an X-linked recessive pattern, called x-linked hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia (XLHED). A condition is considered X-linked if the mutated gene that causes the disorder is located on the X chromosome, one of the two sex chromosomes. In males (who have only one X chromosome), one altered copy of the gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the condition. In females (who have two X chromosomes), a mutation must be present in both copies of the gene to cause the disorder. Males are affected by X-linked recessive disorders much more frequently than females. A striking characteristic of X-linked inheritance is that fathers cannot pass X-linked traits to their sons.[citation needed]

In X-linked recessive inheritance, a female with one altered copy of the gene in each cell is called a carrier. Since females operate on only one of their two X chromosomes (X inactivation) a female carrier may or may not manifest symptoms of the disease. If a female carrier is operating on her normal X she will not show symptoms. If a female is operating on her carrier X she will show symptoms. In about 70 percent of cases, carriers of hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia experience some features of the condition. These signs and symptoms are usually mild and include a few missing or abnormal teeth, sparse hair, and some problems with sweat gland function. Some carriers, however, have more severe features of this disorder.

Treatments

[edit]In January 2013, Edimer Pharmaceuticals, a biotechnology company based in Cambridge, MA, USA, initiated a Phase I, open-label, safety and pharmacokinetic clinical study of EDI200, a drug aimed at the treatment of XLHED. During development in mice and dogs EDI200 has been shown to substitute for the altered or missing protein resulting from the EDA mutation which causes XLHED. A second trial in newborn infants with XLHED tested the synthetic protein in 10 subjects between 2013 and 2016 at 6 sites in the US and Europe.[3] As the treated group "didn’t see significant changes in sweat gland function and other early markers of biologic activity",[4] prenatal administration of the drug was considered.

Following the Edimer trials, Dr. Holm Schneider, the principal investigator of these trials which indicated sufficient safety of the replacement protein,[5] injected EDI200 via amniocentesis with better development of tooth buds and sweat glands than in the postnatal trial and persistent sweating ability in all three treated boys.[6][7]

EDAR or EDARADD (autosomal)

[edit]Less commonly, hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia results from mutations in the EDAR or EDARADD gene. Both EDAR and EDARADD mutations can have an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive pattern of inheritance. Autosomal dominant inheritance means one copy of the altered gene in each cell is sufficient to cause the disorder. Autosomal recessive inheritance means two copies of the gene in each cell are altered. Most often, the parents of an individual with an autosomal recessive disorder are carriers of one copy of the altered gene but do not show signs and symptoms of the disorder.[citation needed]

Terminology

[edit]Thurnam in 1848 reported 2 cases of hypohidrotic form. Similar cases were reported by Guilford and Hutchinson in 1883 and 1886 respectively. Weech, in 1929 introduced the term hereditary ectodermal dysplasia and suggested the term anhidrotic for those with inability to perspire.

Notable individuals

[edit]- Michael Berryman, Saturn Award-nominated character actor

See also

[edit]- Hermann Werner Siemens

- List of cutaneous conditions

- Albert Touraine

- List of radiographic findings associated with cutaneous conditions

- List of dental abnormalities associated with cutaneous conditions

References

[edit]- ^ James, William; Berger, Timothy; Elston, Dirk (2005). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. (10th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ^ Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ^ "Phase 2 Study to Evaluate Safety, Pharmacokinetics, Immunogenicity and Pharmacodynamics/Efficacy of EDI200 in Male Infants With X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia (XLHED) - Full Text View - ClinicalTrials.gov". Retrieved 2018-09-19.

- ^ "X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia | National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias". National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias. Archived from the original on 2018-04-29. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ^ Körber, Iris; Klein, Ophir; Morhart, Patrick; Faschingbauer, Florian; Grange, Dorothy; Clarke, Angus; Bodemer, Christine; Maitz, Silvia; Huttner, Kenneth (2020-04-06). "Safety and immunogenicity of Fc-EDA, a recombinant ectodysplasin A1 replacement protein, in human subjects". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 86 (10): 2063–2069. doi:10.1111/bcp.14301. ISSN 1365-2125. PMC 7495278. PMID 32250462.

- ^ "Babies With XLHED Treated In Utero | National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias". National Foundation for Ectodermal Dysplasias. 2016-12-07. Retrieved 2018-04-29.

- ^ Schneider, Holm; Faschingbauer, Florian; Schuepbach-Mallepell, Sonia; Körber, Iris; Wohlfart, Sigrun; Dick, Angela; Wahlbuhl, Mandy; Kowalczyk-Quintas, Christine; Vigolo, Michele (2018-04-26). "Prenatal Correction of X-Linked Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia". New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (17): 1604–1610. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1714322. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 29694819.

External links

[edit]- GeneReview/NIH/UW entry on Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia

- Hypohidrotic ectodermal dysplasia at NLM Genetics Home Reference