Beersheba

Beersheba

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • Also spelled | Be'er-Sheva (official) Beer Sheva (unofficial) |

From Upper left: Beersheba City Hall, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Negev Museum of Art, view of downtown, Volunteers square, Be'er Sheva at night | |

| Coordinates: 31°15′8″N 34°47′12″E / 31.25222°N 34.78667°E | |

| Country | |

| District | Southern |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ruvik Danilovich |

| Area | |

• Total | 117,500 dunams (117.5 km2 or 45.4 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 260 m (850 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

• Total | 214,162 |

| • Density | 1,800/km2 (4,700/sq mi) |

| Ethnicity | |

| • Jews and others | 96.9% |

| • Arabs | 3.1% |

| Name meaning | Well of the Oath(see also) |

| Website | beer-sheva.muni.il |

Beersheba (/bɪərˈʃiːbə/ beer-SHEE-bə), officially Be'er-Sheva[2] (usually spelled Beer Sheva; Hebrew: באר שבע, romanized: Bəʾēr Ševaʿ, IPA: [ˈbe(ʔ)eʁ ˈʃeva(ʕ)] ; Arabic: بئر السبع, romanized: Biʾr as-Sabʿ, IPA: [biʔr‿as.sabʕ]; lit. 'Well of the Oath' or 'Well of the Seven'[3]), is the largest city in the Negev desert of southern Israel. Often referred to as the "Capital of the Negev", it is the centre of the fourth-most populous metropolitan area in Israel, the eighth-most populous Israeli city with a population of 214,162,[1] and the second-largest city in area (after Jerusalem), with a total area of 117,500 dunams (45 mi2 / 117.5 km2).

Human habitation near present-day Beersheba dates back to the fourth millennium BC. In the Bible, Beersheba marks the southern boundary of ancient Israel, as mentioned in the phrase "From Dan to Beersheba." Initially assigned to the Tribe of Judah, Beersheba was later reassigned to Simeon. During the monarchic era, it functioned as a royal city but eventually faced destruction at the hands of the Assyrians.[3] The Biblical site of Beersheba is Tel Be'er Sheva, lying some 4 km distant from the modern city, which was established at the start of the 20th century by the Ottomans.[4] The city was captured by the British-led Australian Light Horse troops in the Battle of Beersheba during World War I.

The population of the town was completely changed in 1948–49. Bir Seb'a (Arabic: بئر السبع), as it was then known, had been almost entirely Muslim, and the 1947 UN Partition Plan designated it to be part of the Arab state. It was occupied by the Egyptian army from May 1948 until October 1948 when it was captured by the Israel Defense Forces and part of Arab population fled, relocated or was expelled.[5] Today, the metropolitan area is composed of approximately equal Jewish and Arab populations, with a large portion of the Jewish population made up of the descendants of Sephardi Jews and Mizrahi Jews who fled, relocated or were expelled from Arab countries after Israel's founding in 1948, as well as smaller communities of Bene Israel and Cochin Jews from India. Second and third waves of immigration have taken place since 1990, bringing Russian-speaking immigrants from the former Soviet Union as well as Beta Israel immigrants from Ethiopia. The Soviet immigrants have made the game of chess a major sport in Beersheba, and it is now Israel's national chess center, with more chess grandmasters per capita than any other city in the world.[6]

Beersheba is home to Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. This city also serves as a center for Israel's high-tech and developing technology industry.[7] The city has constructed over 250 roundabouts, earning its moniker as the "Roundabouts Capital of Israel" and the largest number of roundabouts in the world.[8][9][failed verification]

Etymology

[edit]The Book of Genesis gives two etymologies for the name Be'er Sheba. Genesis 21:28-31 relates:

Then Abraham set seven ewes apart. And Abimelech said to Abraham, "What mean these seven ewes, which you have set apart? And [Abraham] said, "That you are to take these seven (sheba) ewes from me, to be for me a witness that I have dug this well (bǝ'er)." Therefore the name of that place was Be'er Sheba, for there the two of them had sworn (nishbǝ'u).

Genesis 26 relates:

And Isaac redug the wells which had been dug in the days of Abraham his father, and which the Philistines had sealed after the death of Abraham, and he used the same names as had his father . . . And they arose in the morning, and they swore (wa-yishabǝ'u) each to his fellow, and Isaac sent them off, and they departed him in peace. On that same day, Isaac's men came to him to tell him of the well which they had dug, and they said to him, "We found water." And he called it Shib'a ("seven" normally, possibly "oath" or a proper noun); therefore the name of the city is Be'er Sheba to this day.

The original Hebrew name could therefore relate to the oath of Abraham and Abimelech ('well of the oath') or the seven ewes in that oath ('well of the seven'), as related in Genesis 21:31, and/or to the oath of Isaac and Abimelech in Genesis 26:33. Alternatively, Obadiah Sforno suggested that the well is called Seven because it was the seventh dug; the narrative of Genesis 26 includes three wells dug by Abraham which are reopened by Isaac (Esek, Sitnah, Rehoboth), for a total of six, after which Isaac goes to Beersheba, the seventh well.[10]

The double name of Shib'a and Beersheba is referenced again by the Masoretic Text in Joshua 19:2,[11] usually translated "Beersheba or Sheba"; however the Septuagint reads "Beersheba and Samaa (Σαμαὰ)" which fits with MT 1 Chron. 4:28.

Abraham ibn Ezra and Samuel b. Meir suggest the two etymologies refer to two different cities.[12][13]

During the Ottoman administration, the city was referred as بلدية بئرالسبع (Belediye Birüsseb).[14]

Hebrew Bible

[edit]Beersheba is mainly dealt with in the Hebrew Bible in connection with the Patriarchs Abraham and Isaac, who both dug a well and close peace treaties with King Abimelech of Gerar at the site. Hence it receives its name twice, first after Abraham's dealings with Abimelech (Genesis 21:22–34), and again from Isaac who closes his own covenant with Abimelech of Gerar and whose servants also dig a well there (Genesis 26:23–33). The place is thus connected to two of the three Wife–sister narratives in the Book of Genesis.

According to the Hebrew Bible, Beersheba was founded when Abraham and Abimelech settled their differences over a well of water and made a covenant (see Genesis 21:22–34). Abimelech's men had taken the well from Abraham after he had previously dug it so Abraham brought sheep and cattle to Abimelech to get the well back. He set aside seven lambs to swear that it was he that had dug the well and no one else. Abimelech conceded that the well belonged to Abraham and, in the Bible, Beersheba means "Well of Seven" or "Well of the Oath".[15]

Beersheba is further mentioned in the following Bible passages: Isaac built an altar in Beersheba (Genesis 26:23–33). Jacob had his dream about a stairway to heaven after leaving Beersheba. (Genesis 28:10–15 and 46:1–7). Beersheba was the territory of the tribe of Simeon and Judah (Joshua 15:28 and 19:2). The sons of the prophet Samuel were judges in Beersheba (I Samuel 8:2). Saul, Israel's first king, built a fort there for his campaign against the Amalekites (I Samuel 14:48 and 15:2–9). The prophet Elijah took refuge in Beersheba when Jezebel ordered him killed (I Kings 19:3). The prophet Amos mentions the city in regard to idolatry (Amos 5:5 and 8:14).[16] Following the Babylonian conquest and subsequent enslavement of many Israelites, the town was abandoned. After the Israelite slaves returned from Babylon, they resettled the town. According to the Hebrew Bible, Beersheba was the southernmost city of the territories settled by Israelites, hence the expression "from Dan to Beersheba" to describe the whole kingdom.[16]

Zibiah, the consort of King Ahaziah of Judah and the mother of King Jehoash of Judah,[17] was from Beersheba.

History

[edit]The city has been destroyed and rebuilt many times. Considered unimportant for centuries, Be’er Sheva regained notoriety under Byzantine rule (in the 4th–7th century), when it was a key point on the Limes Palestinae, a defense line built against the desert tribes; however, it fell to the Arabs in the 7th century and to the Turks in the 16th century.

It long remained a watering place and small trade centre for the nomadic Bedouin tribes of the Negev, despite Turkish efforts at town planning and development around 1900. Its capture in 1917 by the British Army opened the way for their conquest of Palestine and Syria. After being taken by Israeli troops in October 1948, Beersheba was rapidly settled by new immigrants and has since developed as the administrative, cultural, and industrial centre of the Negev. It is one of the largest cities in Israel outside of metropolitan Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, and Haifa.

Chalcolithic

[edit]Human settlement in the area dates from the Copper Age. The inhabitants lived in caves, crafting metal tools and raising cattle.[18] Findings unearthed at Tel Be'er Sheva, an archaeological site east of modern-day Beersheba, suggest the region has been inhabited since the 4th millennium BC (between 5000 and 6,000 years ago).[19]

Iron Age Israelite town

[edit]

Tel Be'er Sheva, an archaeological site containing the ruins of an ancient town believed to have been the Biblical Beersheba, lies a few kilometers east of the modern city. The town dates to the early Israelite period, around the 10th century BCE. The site was possibly chosen due to the abundance of water, as evidenced by the numerous wells in the area. According to the Hebrew Bible, the wells were dug by Abraham and Isaac when they arrived there. The streets were laid out in a grid, with separate areas for administrative, commercial, military, and residential use. It is believed to have been the first planned settlement in the region, and is also noteworthy for its elaborate water system; in particular, a huge cistern carved out of the rock beneath the town.

Persian period

[edit]During the Persian rule 539 BC–c. 332 BC Beersheba[dubious – discuss] was at the south of Yehud Medinata autonomous province of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. During that era the city was rebuilt[20] and a citadel had been constructed.[21] Archeological finds from between 359 and 338 BC have been made, finding pottery and an ostracon.[21]

Hellenistic period

[edit]During the Hasmonean rule, the city[dubious – discuss] was not attributed great importance as it was not mentioned when conquered from Edom or described in the Hasmonean wars.[dubious – discuss][20]

Roman and Byzantine periods

[edit]Around 64-63 BC, the Roman general Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus made Beersheba, known as Birosaba, the southern part of the Judea province.[22] During the Herodian period there was a small settlement in Beersheba. Remains of a Jewish village dating back to the first century AD were discovered in the Harkapet neighborhood in the north of the city.[23]

In the following years, the town served as front-line defence against Nabatean attacks and was on the limes belt, which in this region is attributed to the time of Vespasian (1st century AD).[24] The city become the centre of an eparchy around 268.[24] During the Roman and Byzantine periods, the city developed significantly and the burial grounds on the outskirts of the city became residential areas. The inhabitants, which consisted of Nabataeans, Jews and other ethnicities, spoke primarily Greek and lived from olive oil production, viticulture, agricultural and other trades.[25]

After the reforms of Diocletian, the town became part of the province of Palaestina Tertia and grew to an approximate size of 60 hectares during its peak in the 6th century.[22] Beersheba was described in the Madaba Map and Eusebius of Caesarea as a large village with a Roman garrison.[26] The camp was later identified in aerial photographs taken during the First World War and other structures associated with the camp, such as a bath house and dwellings, were found in later excavations.[25]

During the Byzantine period, at least six churches were built there, one of which is the largest church to have been excavated in the Negev. Some of the churches were still in use until the Umayyad period but it remains uncertain whether they continued beyond the early eight century.[22] Monasticism is also attested in historical documents and one structure has been identified as a monastery.[25] Barsanuphius of Gaza corresponded with a certain monk of Beersheba, John, who might be identified with John the Prophet, who between 525 and 527 moved to the monastery of Seridus and together with Barsanuphius wrote over 850 letters on spiritual direction.[27]

Early Muslim period

[edit]During the early Muslim period, some of the Byzantine buildings continued to be used, but there was a slow decline of the city, which was manifested in the demolition of the public buildings and their transformation into a source of raw material for secondary construction. In the second half of the 8th century, the city was apparently abandoned.[28]

Mamluk period

[edit]In 1483, during the late Mamluk era, the pilgrim Felix Fabri noted Beersheba as a city. Fabri also noted that Beersheba marked the southern-most border of "the Holy Land".[29]

Ottoman period

[edit]

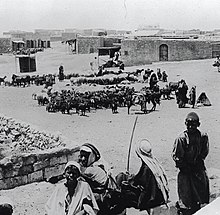

The present-day city was built to serve as an administrative center by the Ottoman administration for the benefit of the Bedouin at the outset of the 20th century and was given the name of Bir al-Sabi (well of the seven). Until World War I, it was an overwhelmingly Muslim township with some 1,000 residents.[30] Ben-David and Kressel have argued that the Bedouin traditional market was the cornerstone for the founding of Beersheba as capital of the Negev during this period,[31]: 3 and Negev Bedouin. Anthropologist and educationalist Aref Abu-Rabia, who worked for the Israeli Ministry of Education and Culture, described it as "the first Bedouin city".[32]: ix

In June 1899, the Ottoman government ordered the creation of the Beersheba sub-district (kaza) of the district (mutasarrıflık) of Jerusalem, with Beersheba to be developed as its capital.[33] Implementation was entrusted to a special bureau of the Ministry of the Interior.[33] The British incorporation of Sinai into Egypt led to a need for the Ottomans to consolidate their hold on southern Palestine.[33] There was also a desire to encourage the Bedouin to become sedentary, with a predicted increase of tranquility and tax revenue.[33] The first governor (kaymakam), Isma'il Kamal Bey, lived in a tent lent by the local sheikh until the government house (Saraya) was built.[34] Kamal was replaced by Muhammed Carullah Efendi in 1901, who in turn was replaced by Hamdi Bey in 1903.[33] The governor in 1908 was promoted to 'adjoint' (mutassarrıf muavin) to the governor of the Jerusalem district, which placed him above the other sub-district governors.[33]

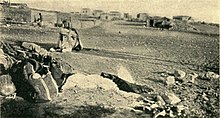

A visitor to Beersheba in May 1900 found only a ruin, a two-storey stone khan, and several tents.[35] By the start of 1901 there was a barracks with a small garrison as well as other buildings.[36] The Austro-Hungarian-Czech orientalist[37] Alois Musil noted in August 1902:

- Bir es-Seba grows from day to day; This year, instead of the tents, we found stately houses along a beautiful road from the Sarayah to the bed of the wadi. In the government building a garden has been laid out, and all sorts of trees have been planted which are sure to prosper, for the few shrubs planted two years ago by the steam mill at the south-east end of the road have grown considerably. The lively construction activity is also causing a lively exploitation of the ruins.[38]

By 1907, there was a large village, military post, a residence for the kaymakam and a large mosque.[39] The population increased from 300 to 800 between 1902 and 1911, and by 1914 there were 1,000 people living in 200 houses.[33]

A plan for the town in the form of a grid was developed by a Swiss and a German architect and two others.[40][41] The grid pattern can be seen today in Beersheba's Old City. Most of the residents at the time were Arabs from Hebron and the Gaza area, although Jews also began settling in the city. Many Bedouin abandoned their nomadic lives and built homes in Beersheba.[42]

First World War and British Mandate

[edit]

During World War I, the Ottomans built a military railroad from the Hejaz line to Beersheba, inaugurating the station on October 30, 1915.[43] The celebration was attended by the Ottoman army commander Jamal Pasha and other senior government officials. The train line was captured by Allied forces in 1917, towards the end of the war. Today, it forms part of the Israeli railway network.[citation needed]

Beersheba played an important role in the Sinai and Palestine Campaign in World War I. The Battle of Beersheba was part of a wider British offensive in aimed at breaking the Turkish defensive line from Gaza to Beersheba. The Ottoman army engaged in three battles with the British forces near Gaza between March 26 and November 7, 1917.[44] Having failed in the First and Second Battles of Gaza, the British succeeded in the Third Battle of Gaza. On October 31, 1917, three months after taking Rafah, General Allenby's troops breached the line of Turkish defense between Gaza and Beersheba.[45] Approximately five-hundred soldiers of the Australian 4th Light Horse Regiment and the 12th Light Horse Regiment of the 4th Light Horse Brigade, led by Brigadier General William Grant, with only horses and bayonets, charged the Turkish trenches, overran them and captured the wells in what has become known as the Battle of Beersheba, called the "last successful cavalry charge in British military history."[46][47] On the edge of Beersheba's Old City is a Commonwealth War Graves Commission Cemetery containing the graves of Australian, New Zealand and British soldiers. The town also contains a memorial park dedicated to them.

During the Palestine Mandate, Beersheba was a major administrative center. The British constructed a railway between Rafah and Beersheba in October 1917 which opened to the public in May 1918, serving the Negev and settlements south of Mount Hebron.[48] In 1928, at the beginning of the tension between the Jews and the Arabs over control of Palestine and wide-scale rioting which left 133 Jews dead and 339 wounded, many Jews abandoned Beersheba, although some returned occasionally. After an Arab attack on a Jewish bus in 1936, which escalated into the 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine, the remaining Jews left.[49]

At the time of the 1922 census of Palestine, Beersheba had a population of 2,356 (2,012 Muslims, 235 Christians, 98 Jews and 11 Druze).[50] At the time of the 1931 census, Beersheba had 545 occupied houses and a population of 2,959 (2,791 Muslims, 152 Christians, 11 Jews and five Baháʼí).[51] The 1938 village survey did not cover Beersheba due to the area's largely nomadic population and the Rural Property Tax Ordinance not being applied there.[52] The 1945 village survey conducted by the Palestine Mandate government found 5,570 (5,360 Muslims, 200 Christians and 10 others).[53]

-

Beersheba, 1948

-

Beersheba police station. 1948. Original building Ottoman with British Mandate addition.

-

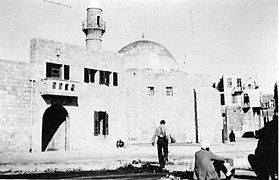

Beersheba mosque, 1948

-

A mosque in Be'ersheva photographed during Operation Yoav, 1948

-

Harel Brigade assembling in Beersheba prior to Operation Horev, 25 December 1948

-

Nahal Beersheba in flood, 1948

State of Israel

[edit]1947–1949 war

[edit]

In 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) proposed that Beersheba be included within the Jewish state in their partition plan for Palestine.[54] However, when the UN's Ad Hoc Committee revised the plan, they moved Beersheva to the Arab state on account of it being primarily Arab.[54][55] Egyptian forces had been stationed at Beersheva since May 1948.

After the Arab states invaded Palestine and declared war on the newly-founded Jewish state of Israel, Yigal Allon proposed the conquest of Beersheba,[56] which was approved by Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion. According to Israeli historian Benny Morris, Allon ordered the "conquest of Beersheba, occupation of outposts around it, [and] demolition of most of the town."[57] The objective was to break the Egyptian blockade of Israeli convoys to the Negev. The Egyptian army did not expect an offensive and fled en masse.[58] Israel bombed the town on October 16.[59] At 4:00 am on October 21, the 8th Brigade's 89th battalion and the Negev Brigade's 7th and 9th battalions moved in. Some troops advanced from the Mishmar HaNegev junction, 20 kilometres (12 mi) north of Beersheba and others from the Turkish train station and Hatzerim. By 9:45, Beersheba was in Israeli hands. Around 120 Egyptian soldiers were taken prisoner. All of the Arab inhabitants who had resisted were expelled.[30] The remaining Arab civilians, 200 men and 150 women and children, were taken to the police fort and, on October 25, the women, children, disabled and elderly were driven by truck to the Gaza border. The Egyptian soldiers were interned in POW camps. Some men lived in the local mosque and were put to work cleaning, however, when it was discovered that they were supplying information to the Egyptian army, they were also deported.[57] The town was subject to large-scale looting by the Haganah, and by December, in one calculation, the total number of Arabs driven out from Beersheva and surrounding areas reached 30,000 with many ending up in Jordan as refugees.[59][60] Following Operation Yoav, a 10-kilometer radius exclusion zone around Beersheba was enforced into which no Bedouin were allowed.[61] In response, the United Nations Security Council passed two resolutions on the November 4 and 16 demanding that Israel withdraw from the area.[62]

First four decades

[edit]Following the conclusion of the war, the 1949 Armistice Agreements formally granted Beersheba to Israel. The town was then transformed into an Israeli city with only an exiguous Arab minority.[30] Beersheba was deemed strategically important due to its location with a reliable water supply and at a major crossroads, northeast to Hebron and Jerusalem, east to the Dead Sea and al Karak, south to Aqaba, west to Gaza and southwest to Al-Auja and the border with Egypt.[58]

After a few months, the town's war-damaged houses were repaired. As a post-independence wave of Jewish immigration to Israel began, Beersheba experienced a population boom as thousands of immigrants moved in. The city rapidly expanded beyond its core, which became known as the "Old City", as new neighborhoods were built around it, complete with various housing projects such as apartment buildings and houses with auxiliary farms, as well as shopping centers and schools. The Old City was turned into a city center, with shops, restaurants, and government and utility offices. An industrial area and one of the largest cinemas in Israel were also built in the city. By 1956, Beersheba was a booming city of 22,000.[63][64] In 1959, during the Wadi Salib riots, riots spread quickly to other parts of the country, including Beersheba.[65]

Soroka Hospital opened its doors in 1960. By 1968, the population had grown to 80,000.[66] The University of the Negev, which would later become Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, was established in 1969. The then Egyptian president Anwar Sadat visited Beersheba in 1979. In 1983, its population was more than 110,000. During the 1990s post-Soviet aliyah, the city's population greatly increased as many immigrants from the former Soviet Union settled there.

Urban development in the 21st century

[edit]

As part of its Blueprint Negev project, the Jewish National Fund funded major redevelopment projects in Beersheba. One such project is the Beersheba River Walk, a 900-acre (3.6-square-kilometre) riverfront park stretching along 8 kilometers of the riverside and containing a 15-acre (6.1-hectare) manmade boating lake, a 12,000-seat amphitheater, green spaces, playgrounds, and a bridge along the route of the city's Mekorot water pipes.[67] The Beersheba River had previously been used as a dumping site and filled with untreated wastewater. After the renovation, the river was transformed and now flows with high-quality purified wastewater.[5] At the official entrance to the river park is the Beit Eshel Park, which consists of a park built around a courtyard with historic remains from the settlement of Beit Eshel.[68]

Four new shopping malls were also built. Among them is Kanyon Beersheba, a 115,000-square-metre (1,240,000-square-foot) ecologically planned mall with pools for collecting rainwater and lighting generated by solar panels on the roof. It will be situated next to an 8,000-meter park with bicycle paths.[68][69][70] In addition, the first ever farmer's market in Israel was established as an enclosed, circular complex with 400 spaces for vendors surrounded by parks and greenery.[68]

A new central bus station was built in the city. The station has a glass-enclosed complex also containing shops and cafés.[68]

Some $10.5 million was also invested in renovating Beersheba's Old City, preserving historical buildings and upgrading infrastructure.[71] The Turkish Quarter was also redeveloped with newly cobbled streets, widened sidewalks, and the restoration of Turkish homes into areas for dining and shopping.[67]

In 2011, city hall announced plans to turn Beersheba into the "water city" of Israel.[72] One of the projects, "Beersheva beach", is a 7-dunam fountain opposite city hall.[73][74] Other projects included fountains near the Soroka Medical Center and in front of the Shamoon College of Engineering.

In the 1990s, as skyscrapers began to appear in Israel, the construction of high-rise buildings began in Beersheba.[75] Today, downtown Beersheba has been described as a "clean, compact, and somewhat sterile-looking collection of high-rise office and residential towers."[76] The city's tallest building is Rambam Square 2, a 32-story apartment building.[77] Many additional high-rise buildings are planned or are under construction, including skyscrapers.[78][79][80] There are further plans to build luxury residential towers in the city.[81]

In December 2012, a plan to build 16,000 new housing units in the Ramot Gimel neighborhood was scrapped in favor of creating a new urban forest, which spans 1,360 acres (550 ha) and serves as the area's "green lung", as part of the plans to develop a "green band" around the city. The forest includes designated picnic areas, biking trails, and walking trails. According to Mayor Ruvik Danilovich, Beersheba still has an abundance of open, underdeveloped spaces that can be used for urban development.[82]

In 2017, a new urban building plan was approved for the city, designed to raise the city's population to 340,000 by 2030. Under the plan, 13,000 more housing units will be built, along with industrial and business developments occupying a total of four million square meters. A second public hospital is also planned.[83] Planning for the Beersheba Light Rail also began.[84] In 2019, the construction of a new public hospital, which will be named after Shimon Peres, was approved. The hospital will be a 345-acre (140 ha) complex that will feature 1,900 beds, commerce, hotel, alternative medicine, and paramedical services, and research centers, with the possibility of apartment units for medical faculty employees, students, and senior housing. It will be linked to the rest of the city by a light rail system.[85]

In 2021, an outline plan was approved for the construction of 34,000 housing units in the city, the plan will lead to an increase in the number of residents living in the city to 400,000.[86]

Security incidents in the city

[edit]On October 19, 1998, sixty-four people were wounded in a grenade attack.[87] On August 31, 2004, sixteen people were killed in two suicide bombings on commuter buses in Beersheba for which Hamas claimed responsibility. On August 28, 2005, another suicide bomber attacked the central bus station, seriously injuring two security guards and 45 bystanders.[88] During Operation Cast Lead, which began on December 27, 2008, and lasted until the ceasefire on January 18, 2009, Hamas fired 2,378 rockets (such as Grad rockets) and mortars, from Gaza into southern Israel, including Beersheba. The rocket attacks have continued, but have been only partially effective since the introduction of the Iron Dome rocket defense system.[89][90][91][92]

In 2010, an Arab attacked and injured two people with an axe.[93][94][95] In 2012, a Palestinian from Jenin was stopped before a stabbing attack in a "safe house".[96][97] On October 18, 2015, a lone gunman shot and killed a soldier guarding the Beersheva bus station before being gunned down by police.[98] In September 2016, the Shin Bet thwarted a Palestinian Islamic Jihad terror attack at a wedding hall in Beersheba.[99][100]

On March 22, 2022, a convicted Islamic State supporter carried out a stabbing and vehicle-ramming attack, killing four people and injuring two others.[101]

During the 2023 Israel–Hamas war, the city became the target of several rocket attacks.[102]

Emblem of Beersheba

[edit]

Since 1950, Beersheba has changed its municipal emblem several times. The 1950 emblem, designed by Abraham Khalili, featured a tamarix tree, a factory and water flowing from a pipeline.[103] In 1972 the emblem was modernized with the symbolic representation of the Twelve Tribes and a tower.[103] Words from the Bible are inscribed: Abraham "planted a tamarisk tree in Beersheba." (Genesis 21:33) Since 2012, it has incorporated the number seven as part of the city rebranding.

Geography

[edit]

Beersheba is located on the northern edge of the Negev desert 115 kilometres (71 mi) south-east of Tel Aviv and 120 kilometres (75 mi) south-west of Jerusalem. The city is located on the main route from the center and north of the country to Eilat in the far south. The Beersheba Valley has been populated for thousands of years, as it has available water, which flows from the Hebron hills in the winter and is stored underground in vast quantities.[104] The main river in Beersheba is Nahal Beersheva, a stream that flows year round and occasionally floods in the winter. The Kovshim and Katef streams are other important wadis that pass through the city. Beersheba is surrounded by several satellite towns, including Omer, Lehavim, and Meitar, and the Bedouin localities of Rahat, Tel as-Sabi, and Lakiya. Just northwest of the city (near Ramot neighborhood) is a region called Goral hills (heb:גבעות גורל lit: hills of fate), the area has hills with up to 500 metres (1,600 feet) above sea level and low as 300 metres (980 feet) above sea level.[105] Due to heavy construction the flora unique to the area is endangered. Northeast of the city (north to the Neve Menahem neighborhood) there are Loess plains and dry river bands.

Climate

[edit]Beersheba has a hot arid climate (Köppen climate classification BWh) bordering upon a hot semi-arid climate (BSh) though with Mediterranean influences. The city has characteristics of both Mediterranean and desert climates. Summers are hot and dry, and winters are mild. Rainfall is highly concentrated in the winter season. In summer, the temperatures are high in daytime and nighttime with an average high of 34.7 °C (94 °F) and an average low of 21.4 °C (71 °F). Winters have an average high of 17.7 °C (64 °F) and average low of 7.1 °C (45 °F). Snow is very rare; a snowfall on February 20, 2015, was the first such occurrence in the city since 2000.[106][107]

Precipitation in summer is rare, most rainfalls come in winter between September and May, but the annual amount is low, averaging 195.1 millimeters (7.7 in) per year. There are sandstorms in summer. Haze and fog are common in winter, as a result of high humidity.

| Climate data for Beersheba | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.5 (88.7) |

35.2 (95.4) |

38.4 (101.1) |

43.8 (110.8) |

44.8 (112.6) |

46.0 (114.8) |

42.0 (107.6) |

43.8 (110.8) |

44.0 (111.2) |

41.7 (107.1) |

38.3 (100.9) |

32.5 (90.5) |

46.0 (114.8) |

| Mean maximum °C (°F) | 24.6 (76.3) |

27.3 (81.1) |

32.0 (89.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

38.7 (101.7) |

39.6 (103.3) |

39.3 (102.7) |

38.3 (100.9) |

38.7 (101.7) |

36.8 (98.2) |

31.9 (89.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

39.6 (103.3) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

18.7 (65.7) |

22.0 (71.6) |

26.5 (79.7) |

30.5 (86.9) |

33.1 (91.6) |

34.7 (94.5) |

34.7 (94.5) |

32.9 (91.2) |

29.7 (85.5) |

25.0 (77.0) |

20.0 (68.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 12.4 (54.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

19.7 (67.5) |

23.2 (73.8) |

26.1 (79.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.1 (82.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

20.7 (69.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.8 (49.6) |

12.8 (55.0) |

16.0 (60.8) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.6 (67.3) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

8.8 (47.8) |

14.4 (57.9) |

| Mean minimum °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

4.0 (39.2) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.2 (45.0) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.4 (59.7) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.4 (65.1) |

16.0 (60.8) |

12.4 (54.3) |

7.5 (45.5) |

4.8 (40.6) |

2.8 (37.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 1.4 (34.5) |

0.5 (32.9) |

2.4 (36.3) |

4 (39) |

8 (46) |

13.6 (56.5) |

15.8 (60.4) |

15.6 (60.1) |

13 (55) |

10.2 (50.4) |

3.4 (38.1) |

3 (37) |

0.5 (32.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 48 (1.9) |

40 (1.6) |

29 (1.1) |

9 (0.4) |

3.6 (0.14) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.5 (0.02) |

9 (0.4) |

18 (0.7) |

38 (1.5) |

195.1 (7.76) |

| Average rainy days | 9 | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 39.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 50 | 48 | 44 | 35 | 34 | 36 | 38 | 41 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 48 | 42 |

| Source 1: Israel Meteorological Service[108][109][110][111] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Israel Meteorological Service[112] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]Beersheba is one of the fastest-growing cities in Israel. Though it has a population of about 200,000, the city is larger in area than Tel Aviv, and its urban plan calls for an eventual population of 450,000–500,000.[113] It is planned to have a population of 340,000 by 2030.[83] The population of Beersheba is predominantly Jewish. Jews and others represent 97.3% of the population, of whom Jews are 86.5%. Arabs constitute around 2.69% of city population.[114][115] The Israel Central Bureau of Statistics divides the Beersheba metropolitan area into two areas:

| Metropolitan ring | Localities | Population (2014 census) | Population density (per km2) |

Annual Population growth rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Israeli Jews | Israeli Arabs | Others[a] | Total | ||||

| Core[b] | 1 | 177,200 | 4,400 | 19,500 | 201,100 | 1,711 | 0.9% |

| Outer Ring[c] | 32 | 35,700 | 124,100 | 500 | 160,300 | 286 | 3.0% |

| Total | 33 | 212,900 | 128,500 | 20,000 | 361,400 | 1277 | 1.8% |

Economy

[edit]

The largest employers in Beersheba are Soroka Medical Center,[117] the municipality, Israel Defense Forces and Ben-Gurion University. A major Israel Aerospace Industries complex is located in the main industrial zone, north of Highway 60. Numerous electronics and chemical plants, including Teva Pharmaceutical Industries, are located in and around the city.

Beersheba is emerging as a high-tech center, with an emphasis on cyber security.[7] A large high-tech park was built near the Be'er Sheva North Railway Station in 2012[118] and a fifth commercial building begun to be constructed. Deutsche Telekom, Elbit Systems, EMC, Lockheed Martin, Ness Technologies, WeWork and RAD Data Communications have opened facilities there, as has a cyberincubator run by Jerusalem Venture Partners.[119] A Science park funded by the RASHI-SACTA Foundation, Beersheba Municipality and private donors was completed in 2008.[118] Another high-tech park is located north of the city near Omer.

An additional three industrial zones are located on the southeastern side of the city – Makhteshim, Emek Sara and Kiryat Yehudit – and a light industry zone between Kiryat Yehudit and the Old City.

Local government

[edit]

The mayor of Beersheba is Ruvik Danilovich,[120] who was deputy mayor under Yaakov Turner.[121]

| Name | Political party | Took office | Left office | Years in office | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | David Tuviyahu | Mapai | 1950 | 1961 | 11 |

| 2 | Ze'ev Zrizi | Mapam | 1961 | 1963 | 2 |

| 3 | Eliyahu Nawi | Mapai | 1963 | 1986 | 23 |

| 4 | Moshe Zilberman | Independent | 1986 | 1989 | 3 |

| 5 | Yitzhak Rager | Likud | 1989 | 1997 | 8 |

| 6 | David Bunfeld | Likud | 1997 | 1998 | 1 |

| 7 | Yaakov Terner | Labor | 1998 | 2008 | 10 |

| 8 | Ruvik Danilovich | Labor, New Way | 2008 |

Educational institutions

[edit]

According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, in 2022, Beersheba has a ca.8,975 preschoolers in ca.300 preschools & kindergartens. A total of 99 schools teaching a student population of ca.45,291: 60 elementary schools with an enrollment of 19,617 (ca.3,200 of whom are entering the 1st grade), and 39 high schools with an enrollment of 16,699. Of Beersheba's 12th graders, 90% earned a Bagrut matriculation certificate in 2022. The city also has several private schools and yeshivot in the religious sector with 3,000 or more students.

Beersheba is home to one of Israel's major universities, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, located on an urban campus in the city (Dalet neighborhood). Other schools in Beersheva are the Open University of Israel, Shamoon College of Engineering (SCE), Kaye Academic College of Education, Practical Engineering College of Beersheba (Hamikhlala ha technologit shel Be'er sheva),[122] and a campus of the Israeli Air and Space College (Techni Be'er sheva ).[123]

Neighborhoods

[edit]After Israeli independence, Beersheba became a "laboratory" for Israeli architecture.[124] Mishol Girit, a neighborhood built in the late 1950s, was the first attempt to create an alternative to the standard public housing projects in Israel. Hashatiah (literally, "the carpet"), also known as Hashekhuna ledugma (the model neighborhood), was hailed by architects around the world.[124] Today, Beersheba is divided into seventeen residential neighborhoods in addition to the Old City and Ramot, an umbrella neighborhood of four sub-districts. Many of the neighbourhoods are named after letters of the Hebrew alphabet, which also have numerical value, but descriptive place names have been given to some of the newer neighborhoods.

Art and cultural institutions

[edit]

In 1953, Cinema Keren, the Negev's first movie theater, opened in Beersheba. It was built by the Histadrut and had seating for 1,200 people.[125] Beersheba is the home base of the Israel Sinfonietta, founded in 1973. Over the years, the Sinfonietta has developed a broad repertoire of symphonic works, concerti for solo instruments and large choral productions, among them Handel's Israel in Egypt, masses by Schubert and Mozart, Rossini's "Stabat Mater" and Vivaldi's "Gloria". World-famous artists have appeared as soloists with the Sinfonietta, including Pinchas Zukerman, Jean-Pierre Rampal, Shlomo Mintz, Gary Karr, and Paul Tortelier.[126] In the 1970s, a memorial commemorating fallen Israeli soldiers designed by the sculptor Danny Karavan was erected on a hill north-east of the city.[127] The Beersheba Theater opened in 1973. The Light Opera Group of the Negev, established in 1980, performs musicals in English every year.[128]

Landmarks in the city include "Abraham's well", a well dating to at least the 12th century CE (now inside a visitors center), and the old Turkish railway station, now the focus of development plans.[129] The Artists House of the Negev, in a Mandate-era building, showcases artwork connected in some way to the Negev.[130]

The Negev Museum of Art reopened in 2004 in the Ottoman Governor's House, and an art and media center for young people was established in the Old City.

In 2009, a new tourist and information center, Gateway to the Negev, was built.[131]

Great Mosque of Beersheba

[edit]

In 1906, during the Ottoman era, the Great Mosque of Beersheba was built with donations collected from the Bedouin residents in the Negev. It was used actively as a mosque until the city fell to Israeli forces in 1948.[132] The mosque was used until 1953 as the city's courthouse. From then until the 1990s, when it was closed for renovations, the building housed an archeological museum, which the city intended to turn into the archeological branch of the Negev Museum.[133] In 2011, however, the Supreme Court of Israel, sitting as the High Court of Justice, ordered the property to be turned into a museum of Islam without reverting to a place of worship.[134]

Transportation

[edit]Beersheba is the central transport hub of southern Israel, served by roads, railways and air. Beersheba is connected to Tel Aviv via Highway 40, the second longest highway in Israel, which passes to the east of the city and is called the Beersheba bypass because it allows travellers from the north to go to southern locations, avoiding the more congested city center. From west to east, the city is divided by Highway 25, which connects to Ashkelon and the Gaza Strip to the northwest, and Dimona to the east. Finally, Highway 60 connects Beersheba with Jerusalem and the Shoket Junction, and goes through the West Bank. On the local level, a partial ring road surrounds the city from the north and east, and Road 406 (Rager Blvd.) goes through the city center from north to south.

Metrodan Beersheba, established in 2003, had a fleet of 90 buses and operates 19 lines in the city between 2003 and 2016, most of which depart from the Beersheba Central Bus Station.[135] These lines were formerly operated by the municipality as the 'Be'er Sheva Urban Bus Services'. Inter-city buses to and from Beersheba are operated by Egged, Dan BaDarom and Metropoline.[136] The intercity bus service was transferred to Dan Be'er Sheva in 25'th of November 2016 and Metrodan Beersheva had been shut down. With the change to Dan Be'er Sheva the company introduced electronic payment stopping pay at the driver which was common in Beersheba.[137]

Israel Railways operates two stations in the city that form part of the railway to Beersheba: the old Be'er Sheva North University station, adjacent to Ben Gurion University and Soroka Medical Center, and the new Be'er Sheva Central station, adjacent to the central bus station. Between the two stations, the railway splits into two, and also continues to Dimona and the Dead Sea factories. An extension is planned to Eilat[138] and Arad.

The Be'er Sheva North University station is the terminus of the line to Dimona. All stations of Israel Railways can be accessed from Beersheba using transfer stations in Tel Aviv and Lod. Until 2012, the railway line to Beersheba used a slow single-track configuration with sharp curves and many level crossings which limited train speed. Between 2004 and 2012 the line was double tracked and rebuilt using an improved alignment and all its level crossings were grade separated. The rebuilding effort cost NIS 2.8 billion and significantly reduced the travel time and greatly increased the train frequency to and from Tel Aviv and Kiryat Motzkin to Beersheba.[139] In addition, Beersheba will be linked to Tel Aviv and Eilat by a new passenger and freight high-speed railway system.[140]

The Beersheba Light Rail is currently planned as a light rail system for the city of Beersheba and outlying communities. There have been plans for a light rail system in Beersheba for many years, and a light rail system appears in the master plan for the city.[141] An agreement was signed for the construction of a light rail system in 1998, but was not implemented. In 2008, the Israeli Finance Ministry contemplated freezing the Tel Aviv Light Rail project and building a light rail system in Beersheba instead, but that did not happen. In 2014, mayor Ruvik Danilovich announced that the light rail system will be built in the city.[142][143][144] In 2017, the Ministry of Transport gave the Beersheba municipality approval to proceed with preliminary planning on a light rail system.[145] In August 2023, the light rail was officially approved. It is expected to be completed by 2033.[146]

Roundabouts

[edit]

In Be'er Sheva there are over 250 roundabouts, giving the city its nickname of "Roundabout Capital of Israel". Many roundabouts, part of Be'er-Sheva's urban oasis project, include fountains, landscaping and sculptures by well-known artists (such as Menashe Kadishman's The Horse Circle and Jeremy Langford's The Drip Circle). Some commemorate famous people and international and local organizations, or mark important events. Some are named after the twin cities of Beer Sheva.[147]

Well-known roundabouts are: Ilan Ramon Circle, Phantom Circle near the Air Force Technical School, Champions Square near Turner Stadium and Conch Arena, Chess Circle, Harp Circle near the Municipal Conservatory and the Be'er-Sheva Performing Arts Center, College Circle, Ben Gurion Circle, Light Circle, Freemasons Circle, Shofarot Circle, Twin Towers Circle.

Hiking

[edit]Beersheba is linked to Hilvan by the Abraham Path.[citation needed]

Sports

[edit]Hapoel Be'er Sheva plays in the Israeli Premier League, the top tier of Israeli football, having been promoted in the 2008–2009 Liga Leumit season. The club has won the Israeli championship five times, in 1975, 1976, 2016, 2017 and 2018, as well as the State Cup in 1997, 2020 and 2022. Beersheba has two other local clubs, Maccabi Be'er Sheva (based in Neve Noy) and F.C. Be'er Sheva (based in the north of Dalet), a continuation of the defunct Beitar Avraham Be'er Sheva. Hapoel play at the Turner Stadium.

Beersheba has a basketball club, Hapoel Be'er Sheva. The team plays at The Conch Arena, which seats 3,000.

Beersheba has become Israel's national chess center; thanks to Soviet immigration, it is home to the largest number of chess grandmasters of any city in the world.[148] The city hosted the World Team Chess Championship in 2005, and chess is taught in the city's kindergartens.[149] The Israeli chess team won the silver medal at the 2008 Chess Olympiad[150] and the bronze at the 2010 Olympiad. The chess club was founded in 1973 by Eliyahu Levant, who is still the driving spirit behind it.[151]

The city has the second largest wrestling center (AMI wrestling school) in Israel. [citation needed] The center is run by Leonid Shulman and has approximately 2,000 students, most of whom are from Russian immigrant families since the origins of the club are in the Nahal Beka immigrant absorption center. Maccabi Be'er Sheva has a freestyle wrestling team, whilst Hapoel Be'er Sheva has a Greco-Roman wrestling team. In the 2010 World Wrestling Championships, AMI students won five medals.[152] Cricket is played under the auspices of Israel Cricket Association. Beersheba is also home to a rugby team, whose senior and youth squads have won several national titles (including the recent Senior National League 2004–2005 championship).[153] Beersheba's tennis center, which opened in 1991, features eight lighted courts, and the Beersheba (Teyman) airfield is used for gliding.

Environmental awards

[edit]In 2012, the Beersheba "ring trail", a 42-kilometer hiking trail around the city, won third place in the annual environmental competition of the European Travelers Association.[154]

Notable people

[edit]

- Orna Banai (born 1966), actress, comedian, and entertainer

- Elyaniv Barda (born 1981), footballer

- Zehava Ben (born 1968), singer

- Avishay Braverman (born 1948), professor and politician, president of the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- Almog Cohen (born 1988), footballer

- Ruvik Danilovich (born 1971), 8th mayor of Be'er Sheva

- Anat Draigor (born 1960), basketball player

- Eli Alaluf (born 1945), politician

- Ronit Elkabetz (1964–2016), actress

- Velvl Greene (1928–2011), Canadian–American–Israeli scientist and academic

- Zvika Hadar (born 1966), comedian and show host

- Boaz Huss (born 1959), professor of Kabbalah at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev

- Ron Kaplan (born 1970), Olympic gymnast

- Victor Mikhalevski (born 1972), chess grandmaster

- David Naccache (born 1967), cryptologist, professor at France's Ecole normale supérieure

- David Newman (born 1956), professor and Dean of Social Science and Humanities, BGU

- Ilan Ramon (1954–2003), Israel's first astronaut; died in the Columbia disaster

- Yehudit Ravitz (born 1956), singer

- Max Steinberg (1989–2014), American-Israeli IDF lone soldier killed in the 2014 Gaza War

- Idan Tal (born 1975), footballer

- Eli Zizov (born 1991), footballer

- Ze'ev Zrizi (1916–2011), second mayor of Beersheba

- Vince Offer (born 1964), infomercial pitchman, screenwriter, actor and director

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit]Beersheba is twinned with:[155]

Adana, Turkey

Adana, Turkey Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Cluj-Napoca, Romania Lyon, France

Lyon, France Niš, Serbia

Niš, Serbia Oni, Georgia

Oni, Georgia Parramatta, Australia

Parramatta, Australia La Plata, Argentina

La Plata, Argentina Seattle, United States

Seattle, United States Montreal, Canada

Montreal, Canada Winnipeg, Canada

Winnipeg, Canada Wuppertal, Germany

Wuppertal, Germany Munich, Germany

Munich, Germany

See also

[edit]- Battle of Beersheba (First World War)

- Beer Sheva Park, Seattle

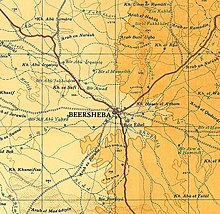

- Map of Beersheba and surrounds in the 1940s and 1950s

- Beersheba Settlement

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "Be'er Sheva Municipality". Archived from the original on June 3, 2021.

- ^ a b Lemche, Niels Peter (2004). Historical dictionary of ancient Israel. Historical dictionaries of ancient civilizations and historical eras. Lanham, Md.: Scarecrow Press. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-0-8108-4848-1.

- ^ Mildred Berman (1965). "The Evolution of Beersheba as an Urban Center". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 55 (2): 308–326. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1965.tb00520.x.

- ^ a b Guide to Israel, Zev Vilnay, Hamakor Press, Jerusalem, 1972, pp.309–14

- ^ "Beersheba Masters Kings, Knights, Pawns", Los Angeles Times, January 30, 2005

- ^ a b "Beersheva: Israel's emerging high-tech hub - Globes English". December 4, 2015. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 4, 2015.

- ^ "Programs > Office of Global Affairs". wvuabroad.wvu.edu. Archived from the original on July 17, 2024. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ "The world's roundabout capital revealed". www.discovercars.com. Archived from the original on March 10, 2024. Retrieved March 10, 2024.

- ^ "Sforno on Genesis 26:33:1". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ David Kimhi and David Altschuler ad loc.

- ^ "Ibn Ezra on Genesis 26:33:1". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Rashbam on Genesis 26:33:1". www.sefaria.org. Retrieved June 15, 2022.

- ^ "Writing to Sultan's Household (Mabeyn-i Hümayun) about precautions will be taken for improving agriculture in Birüsseb District, undated - OpenJerusalem". www.archives.openjerusalem.org. Archived from the original on May 18, 2023. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ^ Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (2000). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

- ^ a b "Beer Sheva". Jewishmag.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ 2 Kings 12:1

- ^ "Beersheba". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. October 21, 1948. Archived from the original on June 29, 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Z. Herzog. Beer-sheba II: The Early Iron Age Settlements. Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University and Ramot Publishing Co. Tel Aviv 1984

- ^ a b "Be'er Sheva". ynet encyclopedia.

- ^ a b Rapport, Arial. מכורש עד אלכסנדר: תולדות ישראל בשלטון פרס. pp. 196–198.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Avni, Gideon (January 30, 2014). The Byzantine-Islamic Transition in Palestine: An Archaeological Approach. OUP Oxford. pp. 24, 258, 355. ISBN 978-0-19-150734-2. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "עדויות להתיישבות של יהודים בב"ש מלפני כ-2,000 שנים התגלו בעיר". הארץ (in Hebrew). Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ a b "The Origin of the Limes Palaestinae and the Major Phases in its Development", in Studien zu den Militärgrenzen Roms, 1967

- ^ a b c Golan, Karni (April 6, 2020). Architectural Sculpture in the Byzantine Negev: Characterization and Meaning. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. pp. 102–103. ISBN 978-3-11-063176-0. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ "The Scripture Gazetteer: A Geographical, Historical, and Statistical Account of the Empires, Kingdoms, Countries, Provinces, Cities, Towns, Villages, Mountains, Valleys, Seas, Lakes, Rivers, &c Mentioned in the Old and New Testaments: Their Ancient History, Natural Productions, and Present State: with an Essay on the Importance and Advantage of the Study of Sacred Geography", volume 1, 1883, p. 308

- ^ Hevelone-Harper, Jennifer L. (November 19, 2019). "The Letter Collection of Barsanuphius and John". In Sogno, Cristiana; Storin, Bradley K.; Watts, Edward J. (eds.). Late Antique Letter Collections: A Critical Introduction and Reference Guide. Univ of California Press. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-520-30841-1. Retrieved April 3, 2024.

- ^ באר שבע בתקופות הרומית עד האסלאמית הקדומה

- ^ Fabri, 1893, pp. 489, 493

- ^ a b c Yitzhak Reiter, Contested Holy Places in Israel–Palestine: Sharing and Conflict Resolution, Archived November 2, 2020, at the Wayback Machine Taylor & Francis, 2017 ISBN 978-1-351-99885-7 p.209.

- ^ Kressel, Gideon M.; Ben-David, Joseph (1996). "Nomadic Peoples" (PDF). Nomadic Peoples (39). The Commission on Nomadic Peoples of the International Union of Anthropological and Ethnological Services (IUAES): 3–28.

- ^ Abu-Rabia, Aref (2001). A Bedouin Century: Education and Development among the Negev Tribes in the 20th century. Berghahn Books. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Yasemin Avcı (2009). "The application of Tanzimat in the desert: The Bedouins and the creation of a new town in Southern Palestine (1860–1914)". Middle Eastern Studies. 45 (6): 969–983. doi:10.1080/00263200903268728. S2CID 144397381.

- ^ 'Aref Abu-Rabi'a (2001). A Bedouin Century. Berghahn Books. pp. 8–10.

- ^ George L. Robinson (1901). "The Wells of Beersheba". The Biblical World. 17 (4): 247–255. doi:10.1086/472788. S2CID 144714359.

- ^ Palestine Exploration Fund, Quarterly Report for April 1901, p100.

- ^ Ernest Gellner, Anthropology and Politics: Revolutions in the Sacred Grove, Basil Blackwell, 1995 pp.212-228.

- ^ Alois Musil (1908). Arabia Petraea. Vol. 2. Wien: A. Hölder. p. 66.

Bir es-Seba wächst von Tag zu Tag; heuer baut man bereits anstatt der Zelte stattliche Häuser, die eine schöne Straße vom Seräja zum Talbette bilden. Beim Regierungsgebäude hat man einen Garten angelegt und allerlei Bäume gesetzt, welche gewiß gut fortkommen werden, denn die wenigen vor zwei Jahren bei der Dampfmühle am Südostende der Straße gepflanzten Sträucher sind inzwischen stark gewachsen. Die rege Bautätigkeit verursacht auch hier eine rege Ausbeutung des Ruinenfeldes.

- ^ George L. Robinson (1908). "Beersheba Revisited". The Biblical World. 31 (5): 322+327–335. doi:10.1086/474045. S2CID 222438761.

- ^ Abu Rabi'a (loc. cit.) names the other two as Palestinian Arabs Sa'id Effendi al-Nashashiby and his assistant, Ragheb Effendi al-Nashashiby.[dubious – discuss] However, Biger (Ottoman Town Planning in Late 19th and early 20th Century Palestine, 3rd International Geography Symposium, 2013, 23–32) says that they were Turks educated in Germany.

- ^ Gerdos, Yehuda (1985). "Basis of Beersheba City Planning". In Na'or, Mordechai (ed.). Settlement of the Negev, 1900–1960 (in Hebrew). Jerusalem, Israel: Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. pp. 167–177.

- ^ Vilnai, Ze'ev (1969). "Be'er Sheva". Ariel Encyclopedia (in Hebrew). Vol. 1. Tel Aviv, Israel: Sifriyat HaSadeh. pp. 473–515.

- ^ Cotterell, Paul (1986). "Chapter 3". The Railways of Palestine and Israel. Abingdon, UK: Tourret Publishing. pp. 14–31. ISBN 978-0-905878-04-1.

- ^ "When we were defeated in Gaza, we lost Palestine". A News. Archived from the original on October 15, 2023. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- ^ An Empire in the Holy Land: Historical Geography of the British Administration in Palestine, 1917–1929, Gideon Biger, St. Martin's Press, New York, Magnes Press, Jerusalem, 1994, pp. 23–24

- ^ "Senate Debates: 60th Anniversary of the State of Israel". March 18, 2008. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ Medlicott, Jeanne (April 21, 2015). "Beersheba Lighthorse Anzac diorama unveiled in Narooma". Narooma News. Archived from the original on August 16, 2015. Retrieved September 7, 2015.

- ^ Gideon Biger (1994), An Empire in the Holy Land, p. 119

- ^ Kark, Ruth; Frantzman, Seth J. (April 2012). "The Negev: Land, Settlement, the Bedouin and Ottoman and British Policy 1871–1948". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies.

- ^ J. B. Barron, ed. (1923). "Table V". Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine. p. 11.

- ^ E. Mills, ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine. p. 7. (online (pdf, 28 MB)

- ^ Village Statistics (PDF). 1938. p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 7, 2023. Retrieved November 18, 2023.

- ^ United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, A/AC.25/Com.Tech/7/Add.1 Archived July 20, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (April 1949)

- ^ a b United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, Report to the General Assembly, September 3, 1947, Volume II, A/364, Add. 1 Archived September 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. UNGA Resolution 181 (November 27, 1947).[1] Archived August 11, 2017, at the Wayback Machine. See boundaries here.

- ^ Anita Shapira, Yigal Allon, Native Son: A Biography, Archived November 24, 2020, at the Wayback Machine University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015 ISBN 978-0-812-20343-1 p.239

- ^ Shapira, Yigal Allon p.245

- ^ a b Morris, Benny. The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited, Cambridge University Press, p. 467.

- ^ a b Shapira, Anita (2007). Yigal Allon: Native Son. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 245. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Alef Abu-Rabia, 'Beersheva,' in Michael Dumper, Bruce E. Stanley (eds.), Cities of the Middle East and North Africa: A Historical Encyclopedia, Archived October 16, 2020, at the Wayback Machine ABC-CLIO, 2007 ISBN 978-1-576-07919-5 p.80.

- ^ Simha Flapan, The Palestinian Exodus of 1948, Archived December 25, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Journal of Palestine Studies, Vol. 16, No. 4 (Summer, 1987), pp. 3–26.

- ^ Morris, Benny (1987) The birth of the Palestinian refugee problem, 1947–1949. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33028-2. p.245.

- ^ Zeev Tzahor, 'The 1949 Air Clash between the Israeli Air Force and the RAF,' Archived December 25, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Journal of Contemporary History, Volume 28, No. 1 (January 1993), pp. 75-101, p.76

- ^ "The Canadian Jewish Chronicle - Google News Archive Search". Archived from the original on August 27, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ "Pittsburgh Post-Gazette - Google News Archive Search". Archived from the original on October 9, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- ^ Jeremy Allouche, The Oriental Communities in Israel, 1948-2003, [2] Archived December 24, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, p.35]

- ^ "How Sea of Immigrants Tamed the Negev Wilderness".[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Jewish National Fund: Be'er Sheva River Park". Jnf.org. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b c d "Beit Eshel Park, Beersheba" Archived November 3, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Blueprint Negev

- ^ "Jewish National Fund plants an emissary in the Bay area" Archived August 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, Jweekly.com

- ^ "404 Error". www.jnf.org. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "Upwelling of Renewal" Archived October 18, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, Times of Israel

- ^ רועי צ'יקי ארד 8 July 2011 00:54 עודכן ב: 23:15. "שיגעון המים של בירת הנגב – חינוך וחברה – הארץ". הארץ. Haaretz.co.il. Archived from the original on September 13, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "mynet באר שבע – תגידו, צריך חוף ים בבאר שבע?". Mynet.co.il. June 20, 1995. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "מקומי – באר שבע nrg – ...דרעי עצבני: רב העיר ב"ש יוצא לקרב". Nrg.co.il. Archived from the original on April 30, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Skyscrapers dotting Tel Aviv landscape | j. the Jewish news weekly of Northern California". Jweekly.com. March 29, 1996. Archived from the original on October 12, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Beersheba desert bloom" Archived November 5, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, Global Travel

- ^ "Rambam Square 2, Beer Sheva". IL /: Emporis.com. July 21, 2003. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "All buildings | Buildings". Emporis. July 21, 2003. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "Rambam Square 2 | Buildings". IL /: Emporis. July 21, 2003. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ "skyscrapers | Buildings". Emporis. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ קוריאל, אילנה (May 12, 2012). "ynet מגדלים בלב המדבר: תנופת הבנייה מגיעה לב"ש – כלכלה". Ynet. Ynet.co.il. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Curiel, Ilana (June 20, 1995). "Beersheba opts for trees over urban sprawl – Israel Environment, Ynetnews". Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com. Archived from the original on January 2, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ a b "Beer Sheva to have population of 340,000 by 2030". Globes. February 8, 2017. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "Planning of Be'er-Sheva's New Light Rail Begins". City of Beer Sheva. Archived from the original on October 9, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ "New hospital approved for Beersheba to enhance healthcare to periphery". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. December 3, 2019. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- ^ נרדי, גיא (December 19, 2021). "אושרה תוכנית המתאר של באר שבע: תוספת של 400 אלף תושבים". Globes. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ גולן, מאת גדי (October 20, 1998). "64 פצועים, מהם שניים קשה ושלושה בינוני, בפיגוע בתחנה המרכזית בבאר שבע". Globes. Archived from the original on May 2, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "Palestinian Bomber Kills Only Himself Near Israeli Bus Station" Archived May 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, New York Times

- ^ "חדשות – צבא וביטחון nrg – ...כיפת ברזל יירטה שתי רקטות". Nrg.co.il. October 31, 2011. Archived from the original on February 3, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ קוריאל, אילנה (August 16, 2011). "ynet גראד דוחה מחאה? "גם ספטמבר לא יזיז אותנו" – חדשות". Ynet. Ynet.co.il. Archived from the original on May 23, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "חדשות – צבא וביטחון nrg – ...רקטה התפוצצה בבאר שבע; חיל". Nrg.co.il. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "חדשות – צבא וביטחון nrg – ...הרוג ושישה פצועים בפגיעות". Nrg.co.il. Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "פיגוע בבאר-שבע: ערבי תקף בגרזן ופצע שניים | שלימות הארץ | חדשות". Hageula.com. June 27, 2011. Archived from the original on May 16, 2013. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "באר שבע: כוחות גדולים במצוד אחר "התוקף בפטיש" – וואלה! חדשות". News.walla.co.il. June 28, 2011. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "אלמוני תקף שני גברים בפטיש ליד עיריית באר שבע – וואלה! חדשות". News.walla.co.il. June 28, 2011. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "נענע10 – סוכל ניסיון פיגוע בבאר שבע: פלסטיני שתכנן לבצע פיגוע דקירה נעצר בדירת מסתור בעיר – חדשות". News.nana10.co.il. June 17, 2009. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "חדשות 2 – סוכל פיגוע דקירה בבאר שבע: מחבל נעצר בדירת מסתור". Mako.co.il. January 4, 2012. Archived from the original on April 18, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ Sterman, Adiv; Gross, Judah Ari. "Terrorist opens fire at Beersheba bus station, kills one, wounds 11". www.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on May 27, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "Islamic Jihad terror attacks in Beer Sheva thwarted". BICOM. October 21, 2016. Archived from the original on January 1, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2018.

- ^ "i24NEWS". www.i24news.tv. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ staff, T. O. I. "Assailant in deadly Beersheba attack was terror convict who backed Islamic State". www.timesofisrael.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2022. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ Fabian, Emanuel. "Rocket sirens sound in Beersheba; Hamas claims responsibility". www.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved October 15, 2023.

- ^ a b "סמל העיר". עיריית באר שבע. Archived from the original on April 26, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ "The climate of Beer Sheva". Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ טייג, אמיר (March 29, 2010). "כל חייל שניווט פעם בגבעות גורל ישמח לשמוע שאת הג'בלאות החשופות החליפו וילות עם גינות פורחות". TheMarker. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Raved, Ahiya (February 20, 2015). "Be'er Sheva rejoices after rare snowfall". Ynetnews. Archived from the original on July 2, 2018. Retrieved June 8, 2015.

- ^ Christine Hauser (January 29, 2000). "Snow falls in Israel's Negev Desert". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved June 24, 2021.

- ^ "Averages and Records for Beersheba (Precipitation, Temperature and Records [Excluding January and June] written in the page) between 1981 and 2000". Israel Meteorological Service. August 2011. Archived from the original on September 14, 2010.

- ^ "Records Data for Israel (Data used only for January and June)". Israel Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- ^ "Temperature average". Israel Meteorological Service. Archived from the original on June 18, 2013. Retrieved December 8, 2011.(in Hebrew)

- ^ "Precipitation average". Archived from the original on September 25, 2011. Retrieved July 12, 2011.(in Hebrew)

- ^ "הסבר לקובץ ערכי טמפרטורה 2013" (PDF). Israel Meteorological Service. 2013. p. 11. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 30, 2016.

- ^ The Blueprint Negev and the Future of Israel (October 18, 2012). "The Blueprint Negev and the Future of Israel | Jerusalem Post – Blogs". Blogs.jpost.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2012. Retrieved March 12, 2013.

- ^ "Regional Statistics". Archived from the original on July 13, 2023. Retrieved July 18, 2021.

- ^ "תוכנית באר שבע אושרה; המטרה – מיליון תושבים עד שנת 2020". Calcalist.co.il. June 20, 1995. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "LOCALITIES, POPULATION AND DENSITY PER SQ. KM. BY METROPOLITAN AREA" (PDF). Archived from the original on October 12, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "About Soroka University Medical Center". hospitals.clalit.co.il. Archived from the original on November 22, 2017. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ a b "Dun's 100 2007 – Be'er-Sheva Municipality VP". Duns100.dundb.co.il. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ Bousso, Nimrod (April 24, 2015). "Desert Storm: Be'er Sheva Rapidly Emerges as Global Cyber Center". Ha'aretz. Archived from the original on October 18, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2015.

- ^ Halon, Eytan (January 11, 2020). "Beersheba rises as Israel's new tech hub". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Archived from the original on January 22, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ Cashman, Greer Fay (November 2, 2013). "Grapevine: Political successes – and successors". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Archived from the original on October 7, 2020. Retrieved December 30, 2020.

- ^ "technical college website". Tcb.ac.il. Archived from the original on January 13, 2012. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "school website". Techni-bs.iscool.co.il. Archived from the original on May 5, 2019. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Haaretz.com, "Magic Carpet: The Carpet-Style Patio Homes of Be'er Sheva"], Haaretz

- ^ Be'er-Sheva Tours and Trails, Adi Wolfson and Zeev Zivan, 2017, p.20

- ^ Sounds from the South Archived October 9, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "h2g2 – Be'er Sheva, Israel – A4499625". BBC. Archived from the original on May 31, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ "The salons of the South – Haaretz – Israel News". Haaretz. December 24, 2006. Retrieved May 5, 2009.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Blueprint for Beersheba" Archived September 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, JPost

- ^ "Touch and feel the Negev" Archived May 29, 2021, at the Wayback Machine, JPost

- ^ Lubliner, Elan (February 21, 2009). "'Gateway' center aims to help the Negev bloom again". Jerusalem Post. Around Israel. Archived from the original on August 13, 2011. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ^ "In latest attack on Palestinian heritage, Israel reopens museum in old mosque", Al Akhbar Newsletter, December 22, 2014, archived from the original on February 25, 2017, retrieved January 23, 2015

- ^ "Will Be'er Sheva allow Muslims to use city's only mosque? – Haaretz – Israel News". Haaretz. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved July 7, 2009.

- ^ Curiel, Ilana (June 24, 2011). "Beersheba mosque to become Islam museum". Yediot Ahronot. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 18, 2015.

- ^ "Transportation in the Negev". Negev Information Center. Archived from the original on June 14, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ "Map of lines of the Metropoline company" (in Hebrew). Metropoline. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ "תשלום עבור נסיעה - דן באר שבע". www.danbr7.co.il. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ^ Hazelkorn, Shahar (March 17, 2008). "Mofaz Decided: A Railway to Eilat Will Be Built". Ynet (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved March 25, 2008.

- ^ Bocker, Ran (July 15, 2012). "From Beersheva to Tel Aviv in 55 Minutes". Ynet (in Hebrew). Archived from the original on July 17, 2012. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- ^ "Eilat high speed rail line gets green line". Airrailnews.com. February 14, 2013. Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "mynet באר שבע – רכבת קלה? הצחקתם את הבאר שבעיים". Mynet.co.il. June 20, 1995. Archived from the original on January 26, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "נחתם ההסכם הסופי לתכנון רכבת קלה בבאר שבע - גלובס". Globes. January 13, 1998. Archived from the original on August 15, 2016. Retrieved August 8, 2016.

- ^ ""מספיק להגר למרכז - יש כאן דירות בחצי מיליון שקל, והרבה מהן" - Bizportal". Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ "Tel Aviv light rail project may be stopped in its tracks". May 26, 2008. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved August 12, 2015.

- ^ "Beer-Sheva develops light rail plans". July 11, 2017. Archived from the original on May 18, 2019. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- ^ Be’er Sheva light rail project to proceed

- ^ איליה יגורוב, 7 כיכרות 7 סיפורים Archived June 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, אתר באר שבע נט, 12 בינואר 2020

- ^ Bekerman, Eitan (September 4, 2006). "Chess masters set to compete in world blitz championship". Haaretz. Archived from the original on October 11, 2008.

- ^ "World Team Championship in Beer Sheva, Israel". World Chess Federation. November 1, 2005. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Tzahor, Uri (November 26, 2008). "Israel takes silver medal at Chess Olympiad". Ynewnews.com. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved November 24, 2010.

- ^ Gavin Rabinowitz (December 12, 2004). "Beersheba is king of world chess". Jerusalem Post. p. 4. Archived from the original on June 14, 2011.

By all accounts it is Levant, 76, who is responsible for chess taking root in these arid surroundings... Klenburg says the club's success is all owed to Levant. "He was the right man at the right time,"

- ^ "mynet באר שבע – באר שבע מובילה במאבק על ספורט ההאבקות". Mynet.co.il. Archived from the original on August 6, 2017. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- ^ "ミニ". Archived from the original on May 29, 2007. Retrieved December 31, 2005.

- ^ Wolfson, Prof Adi (June 20, 1995). "Beersheba wins EU's green travel award". Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "ערים תאומות". beer-sheva.muni.il (in Hebrew). Beersheba. Archived from the original on October 1, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2020.

Bibliography

[edit]- Fabri, Felix (1893). Felix Fabri (circa 1480–1483 A.D.) vol II, part II. Palestine Pilgrims' Text Society.

- Thareani-Sussely, Yifat (2007). "The 'Archaeology of the Days of Manasseh' Reconsidered in the Light of Evidence From The Beersheba Valley". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. 139 (2): 69–77. doi:10.1179/003103207x194091. S2CID 161326436.

External links

[edit]![]() Beer Sheva travel guide from Wikivoyage

Beer Sheva travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Be'er Sheva Municipal Website Archived August 7, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- My Be'er-Sheva

- Beersheba City Council Archived September 24, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- Selection of photos from Beer Sheva from flickr

- Ben-Gurion University

- The city of Beersheba: a tourist's guide

- Beer-Sheva – Historical article from the Catholic Encyclopaedia

- Light Horse charges again Article written by Martin Chulov, published in The Australian, November 1, 2007, the descendants of the Australian light-horsemen rode into the centre of Beersheva, re-enacting the gallant gallop of October 31, 1917

- Israel Builds Expansion and architecture of Beersheva in the 1960s and 1970s

- Blueprint for Beersheba

- Goodchild, Philip; Talbert, Andrew (2010). "Beersheba & Abraham". Bibledex in Israel. Brady Haran for the University of Nottingham.

- Tsagai Asamain, Be'er Sheva-Compound C:Conservation measures during the excavation, Israel Antiquities Authority Site – Conservation Department

- Yardena Etgar and Ofer Cohen, Tel Be’er Sheva: The Underground Water Reservoir System, Israel Antiquities Authority Site – Conservation Department

- Shauli Sela and Fuad Abu-Taa, The Turkish Mosque and the Governor's House: Conservation of the stone and plaster, Israel Antiquities Authority Site – Conservation Department

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 24: IAA, Wikimedia commons

- BeerSheva.city, the first French portal of the city