Criticism of Amazon

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Amazon.com has drawn criticism from multiple sources, where the ethics of certain business practices and policies have been drawn into question. Amazon has faced numerous allegations of anti-competitive or monopolistic behavior, as well as criticisms of their treatment of workers and consumers. Concerns have frequently been raised regarding the availability or unavailability of products and services on Amazon platforms, as Amazon is considered a monopoly due to its size.

Anti-competitive practices

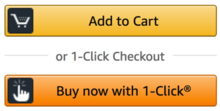

One-click patent

The company has been controversial for its alleged use of patents as a competitive hindrance. The "1-Click patent"[1] is perhaps the best-known example of this. Amazon's use of the 1-click patent against competitor Barnes & Noble's website led the Free Software Foundation to announce a boycott of Amazon in December 1999.[2] The boycott was discontinued in September 2002.[3] On February 22, 2000, the company was granted a patent covering an Internet-based customer referral system, or what is commonly called an "affiliate program". Industry leaders Tim O'Reilly and Charlie Jackson spoke out against the patent,[4] and O'Reilly published an open letter[5] to Jeff Bezos, the CEO of Amazon, protesting the 1-click patent and the affiliate program patent, and petitioning him to "avoid any attempts to limit the further development of Internet commerce". O'Reilly collected 10,000 signatures[6] with this petition. Bezos responded with his own open letter.[7] The protest ended with O'Reilly and Bezos visiting Washington, D.C., to lobby for patent reform. On February 25, 2003, the company was granted a patent titled "Method and system for conducting a discussion relating to an item on Internet discussion boards".[8] On May 12, 2006, the USPTO ordered a re-examination of the "1-Click" patent, based on a request filed by actor Peter Calveley, who cited the prior art of an earlier e-commerce patent and the Digicash electronic cash system.[9]

Canadian site

Amazon has a Canadian site in both English and French, but until a ruling in March 2010, was prevented from operating any headquarters, servers, fulfillment centers or call centers in Canada by that country's legal restrictions on foreign-owned booksellers.[10] Instead, Amazon's Canadian site originates in the United States, and Amazon has an agreement with Canada Post to handle distribution within Canada and for the use of the Crown corporation's Mississauga, Ontario shipping facility.[11] The launch of Amazon.ca generated controversy in Canada. In 2002, the Canadian Booksellers Association and Indigo Books and Music sought a court ruling that Amazon's partnership with Canada Post represented an attempt to circumvent Canadian law,[12] but the litigation was dropped in 2004.[13]

In January 2017, doormat products with the Indian flag on them went on sale on the Amazon Canada website. The use of the Indian flag in this way is considered offensive to the Indian community and in violation of the Flag code of India.[14] The Minister of External Affairs of India, Sushma Swaraj, threatened a visa embargo for Amazon officials if Amazon did not tender an unconditional apology and withdraw all such products.[15][16]

In January 2017, Amazon.ca was required by the Competition Bureau to pay a $1M penalty, plus $100,000 in costs, overpricing practices for failing to provide "truth in advertising" according to Josephine Palumbo, the deputy commissioner for deceptive marketing practices. This fine was levied because some products on Amazon.ca were shown with an artificially high "list price", making the lower selling price appear to be very attractive, producing an unfair competitive edge over other retailers. This is a frequent practice among some retailers and the fine was intended to "send a clear message [to the industry] that unsubstantiated savings claims will not be tolerated".[17] The Bureau also indicated that the company has made changes to ensure that regular prices are more accurately listed.[18]

BookSurge

In March 2008, sales representatives of Amazon's BookSurge division started contacting publishers of print on demand (POD) titles to inform them that for Amazon to continue selling their POD books, they were required to sign agreements with Amazon's own BookSurge POD company. Publishers were told that eventually, the only POD titles that Amazon would be selling would be those printed by their own company, BookSurge. Some publishers felt that this ultimatum amounted to monopoly abuse, and questioned the ethics of the move and its legality under anti-trust law.[19]

Direct selling

In 2008, Amazon UK came under criticism for attempting to prevent publishers from direct selling at discount from their own websites. Amazon's argument was that they should be able to pay the publishers based on the lower prices offered on their websites, rather than on the full recommended retail price (RRP).[20][21]

Also in 2008, Amazon UK drew criticism in the British publishing community following their withdrawal from sale of key titles published by Hachette Livre UK. The withdrawal was possibly intended to put pressure on Hachette to provide levels of discount described by the trade as unreasonable. Curtis Brown's managing director Jonathan Lloyd opined that "publishers, authors, and agents are 100% behind [Hachette]. Someone has to draw a line in the sand. Publishers have given 1% a year away to retailers, so where does it stop? Using authors as a financial football is disgraceful."[22][23]

In August 2013, Amazon agreed to end its price parity policy for marketplace sellers in the European Union, in response to investigations by the UK Office of Fair Trade and Germany's Federal Cartel Office.[24] It is not yet clear if this ruling applies to direct selling by publishers.

Price control

Following the announcement of the Apple iPad on January 27, 2010, Macmillan Publishers entered into a pricing dispute with Amazon regarding electronic publications. Macmillan asked Amazon to accept a new pricing scheme it had worked out with Apple, raising the price of e-books from $9.99 to $15.[25] Amazon responded by pulling all Macmillan books, both electronic and physical, from their website (although affiliates selling the books were still listed). On January 31, 2010, Amazon "capitulated" to Macmillan's pricing request.[26]

In 2014, Amazon and Hachette became involved in a dispute over agency pricing.[27] Agency pricing is when the agent (such as Hachette) determines the price of a book; normally, however, Amazon dictates the discount level of a book. High-profile authors became involved; hundreds of writers, including Stephen King and John Grisham, signed a petition saying "We encourage Amazon in the strongest possible terms to stop harming the livelihood of the authors on whom it has built its business. None of us, neither readers nor authors, benefit when books are taken hostage."[27] Author Ursula K. Le Guin commented on Amazon's practice of making Hachette books harder to buy on its site, stating "We're talking about censorship: deliberately making a book hard or impossible to get, 'disappearing' an author." Although her statement was met with some outrage and disbelief, Amazon's actions such as eliminating discounts, delaying the delivery time, and refusing pre-publication orders did make physical Hachette books harder to get. Plummeting sales of Hachette books on Amazon indicated that its policies likely succeeded in deterring customers.[28]

On August 11, 2014, Amazon removed the option to preorder Captain America: The Winter Soldier in an effort to gain control over the online pricing of Disney films. Amazon has previously used similar tactics with Warner Bros. and Hachette Book Group. The conflict was resolved in late 2014 with neither having to concede anything. Then in February 2017, Amazon again began to block preorders of Disney films, just before Moana and Rogue One were due to be released to the home market.[29]

The law firm Hagens Berman filed a lawsuit in district court in New York in January 2021, alleging that Amazon colluded with leading publishers to keep e-book prices artificially high. The state of Connecticut also announced it was investigating Amazon for potential anti-competitive behaviour in its sale of e-books.[30]

Removal of competitors' products

On October 1, 2015, Amazon announced that Apple TV and Google Chromecast products were banned from sale on Amazon by all merchants, with no new listings allowed effective immediately, and all existing listings removed effective October 29, 2015. Amazon argued that this was to prevent "customer confusion", as these devices do not support the Amazon Prime Video ecosystem. This move was criticized, as commentators believed that it was meant primarily to suppress the sale of products deemed as competition to Amazon Fire TV products, given that Amazon itself had deliberately refused to offer software for its own streaming services on these devices, and the action contradicted the implication that Amazon was a general online retailer.[31][32][33]

In May 2017, it was reported that Apple and Amazon were nearing an agreement to offer Prime Video on Apple TV, and allow the product to return to the retailer.[34] Prime Video launched on Apple TV December 6, 2017,[35] with Amazon beginning to sell the Apple TV product again shortly thereafter.

Amazon is known to remove products for trivial policy violations by third-party sellers that compete with Amazon's home-grown brands. To compete for product placement where Amazon's own brands are featured prominently, third-party sellers often need to resort to advertisement spends and list themselves with Amazon's expensive Prime program for which they are charged a premium on order fulfillment and returns, resulting in increased costs and lower profit margins.[36]

Amazon has since suppressed other Google products, including Google Home (which competes with Amazon Echo), Pixel phones, and recent products of Google subsidiary Nest Labs (despite the Nest Learning Thermostat having integration support for Amazon's voice assistant platform Alexa). In retaliation, Google announced on December 6, 2017, that it would block YouTube from the Amazon Echo Show and Amazon Fire TV products.[37][38][39][40] In December 2017, Amazon stated that it intended to start offering Chromecast again (which it would do a year later).[41] Meanwhile, Nest stated that it would no longer offer any of its future stock to Amazon until it commits to offering its entire product line.[42]

In April 2019, Amazon announced that it would add Chromecast support to the Prime Video mobile app and release its Android TV app more widely, while Google announced that it would, in return, restore access to YouTube on Fire TV (but not Echo Show).[43] Prime Video for Chromecast and YouTube for Fire TV were both released July 9, 2019.[44]

In December 2019, following the acquisition of Honey—a browser extension that automatically applies online coupons on online stores—by PayPal, the Amazon website began to display warnings advising users to uninstall the software, claiming it was a security risk.[45][46]

Apple partnership

In November 2018, Amazon reached an agreement with Apple Inc. to sell selected products through the service, via the company, selected Apple Authorized Resellers, and vendors who meet specific criteria. As a result of this partnership, only Apple Authorized Resellers and vendors who purchase $2.5 million in refurbished stock from Apple every 90 days (via the Amazon Renewed program) may sell Apple products on the service.[47][48][49] The partnership has faced criticism from independent resellers, who believe that this deal has restricted their ability to sell refurbished Apple products on Amazon at a low cost. In August 2019, The Verge reported that Amazon was being investigated by the FTC over the deal.[50]

Marketplace participant and owner

Amazon has raised concerns by being both the owner of a dominant marketplace and a retail seller in that marketplace. Amazon uses the data it gets from the entire marketplace (data not available to other retailers in the marketplace) to determine what products would be advantageous to produce in-house, at what price point.[51] The company markets products under AmazonBasics, Lark & Ro,[52] and various other private-label brands. U.S. presidential candidate, Elizabeth Warren has proposed, forcing Amazon to sell AmazonBasics and Whole Foods Market, where Amazon competes against other marketplace participants as a brick-and-mortar retailer.[53]

Tim O'Reilly, comparing Ingram's business with Amazon's, noted that Amazon exclusive focus on just the customer debilitates the rest of the retail ecosystem, including sellers, manufacturers, and even its own employees, while Ingram seeks to innovate and build on behalf of all the stakeholders in the marketplace it operates in. O'Reilly adds that Amazon's ecosystem-crippling behaviour is driven by the its insatiable need for growth at all costs.[54]

Third-party sellers have long accused Amazon's rent-seeking behaviour like steadily increasing cost of doing business on their platform, abusing their dominant market position to manipulate pricing, copying popular products of third-party retailers, and unjustifiably promoting its own brands.[36]

In October 2021, based on several leaked internal documents, Reuters reported that Amazon systematically harvested and studied data about their sellers' products' market performance, and used those data to identify lucrative markets and ultimately launch Amazon's replacement products in India. The data included information about returns, the sizing of clothing down to the neck circumference and sleeve length, and the volume of product views on their website. Rivals' market performance data are not available to Amazon's sellers. The strategy also involved tweaking the search results to favor Amazon's private-label products. The Solimo Strategy's impact had a reach well beyond India: hundreds of Solimo branded household items, from multivitamins to coffee pods, are available in the US. One of the victims of the Solimo Strategy is the clothing brand John Miller, owned by India's 'retail king' Kishore Biyani.[55]

In October 2022, a £900 million class-action lawsuit was filed in the United Kingdom against Amazon, over a "Buy Box" feature on its website which "favours products sold by Amazon itself, or by retailers who pay Amazon for handling their logistics".[56][57]

Antitrust complaints

The European Commission commenced an investigation in June 2015 regarding clauses in Amazon's e-book distribution agreements which potentially breached EU antitrust rules by making it harder for other e-book platforms to compete. This investigation was concluded in May 2017 when the Commission adopted a decision which rendered binding Amazon's commitments not to use or enforce these clauses.[58]

In July 2019 and in November 2020, the European Commission opened two in-depth investigations into Amazon's use of marketplace seller data as well as possible preferential treatment of Amazon's own retail offers and those of marketplace sellers that use Amazon's logistics and delivery services. It charged that Amazon systematically relies on nonpublic data it gathers from third party sellers to unfairly compete against them, to the benefit of its own retail business, thus violating competition law in the European Economic Area.[59][60] On June 11, 2020, the European Union announced that it will be pressing charges against Amazon over its treatment of third-party e-commerce sellers.[61] The state of California opened an investigation around the same time.[62]

In December 2019, the Competition Commission of India suspended an approval for the strategic takeover of Future Retail and levied a penalty of Rs 200 crores. The regulator discovered through internal emails of Amazon that it intended to acquire the company so that it can take advantage of foreign investment relaxations and not owing to its interest in the company. Amazon appealed this order in the Company tribunal. Later in March 2022, the CCI defended its order in court citing misrepresentation on the part of Amazon.[63][64]

In July 2020, Amazon along with other tech giants Apple, Google and Meta was accused of maintaining harmful power and anti-competitive strategies to quash potential competitors in the market.[65] The CEOs of respective firms appeared in a teleconference on July 29, 2020, before the lawmakers of the U.S. House Antitrust Subcommittee.[66] In October 2020, the antitrust subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives released a report accusing Amazon of abusing a monopoly position in e-commerce to unfairly compete with sellers on its platform.[67] In a March 2022 letter to bipartisan leaders of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Biden's Justice Department endorsed legislation forbidding large digital platforms like Amazon from disadvantaging competitors' products and services against their own. "The [Justice] Department views the rise of dominant platforms as a presenting a threat to open markets and competition, with risks for consumers, businesses, innovation, resiliency, global competitiveness, and our democracy," says the letter.[68]

California's Attorney General filed suit against Amazon in September 2022, following the investigation that began in 2020, alleging that its contracts with third-party sellers and wholesalers inflate prices and stifle competition. Specifically, that merchants are coerced into contracts that prevent them from offering their products elsewhere, on other websites, for lower prices.[69]

Treatment of workers

Amazon has faced various critiques over the quality of its working environments and treatment of its workforce. A group known as The FACE (Former And Current Employees) of Amazon has regularly used social media to disseminate criticism of the company and allegations regarding negative work conditions.[70][71]

Employee mismanagement

Amazon has been accused of mistakenly firing people on medical leave for no-shows, not fixing inaccuracy in their payroll systems resulting in a section of both its blue-collar and white-collar employees going under-paid for months, and violating employment laws by deliberately denying unpaid leaves.[72]

Opposition to trade unions

Amazon has opposed efforts by trade unions to organize in both the United States and the United Kingdom. In 2001, 850 employees in Seattle were laid off by Amazon after a unionization drive. The Washington Alliance of Technological Workers (WashTech) accused the company of violating union laws and claimed Amazon managers subjected them to intimidation and heavy propaganda. Amazon denied any link between the unionization effort and layoffs.[73] Also in 2001, Amazon.co.uk hired a US management consultancy organization, The Burke Group, to assist in defeating a campaign by the Graphical, Paper and Media Union (GPMU, now part of Unite the Union) to achieve recognition in the Milton Keynes distribution depot. It was alleged that the company victimized or sacked four union members during the 2001 recognition drive and held a series of captive meetings with employees.[74]

An Amazon training video that was leaked in 2018 stated "We are not anti-union, but we are not neutral either. We do not believe unions are in the best interest of our customers or shareholders or most importantly, our associates." The video also encouraged to report "warning signs" of potential worker organization, which included workers using words like "living wage", employees "suddenly hanging out together" as well as workers showing "unusual interest in policies, benefits, employee lists, or other company information".[75][76] In early 2020, Amazon internal documents were leaked, which said that Whole Foods was using a heat map to track which of its 510 stores had the highest levels of pro-union sentiment. Factors including racial diversity, proximity to other unions, poverty levels in the surrounding community and calls to the National Labor Relations Board were named as contributors to "unionization risk".[77] Data collected in the heat map suggest that stores with low racial and ethnic diversity, especially those located in poor communities, are more likely to unionize. Amazon also had a job listing for an Intelligence Analyst, whose role it would be to identify and tackle threats to Amazon, which included unions and organised labour.[78][79]

On 4 December 2020, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) found that Amazon illegally fired two employees n retaliation for efforts to organize workers.[80] In April 2021, after a majority of workers in Bessemer, Alabama voted against joining the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, the union asked for a hearing with the NLRB to determine whether the company created "an atmosphere of confusion, coercion and/or fear of reprisals" ahead of the union vote.[81] The vote had been met with "anti-union" signs and mandatory "union education meetings" according to Amazon worker Jennifer Bates.[82] During the voting, President Joe Biden made a speech acknowledging the organizing workers in Alabama and called for "no anti-union propaganda".[83] This was followed by an increase of activity by public relations staff on Twitter, reportedly at the personal direction of Jeff Bezos. The tone used by some of the posts led one Amazon engineer to initially suspect that the accounts had been hacked.[84] Some of the criticism of unions came from generic recently created accounts rather than known Amazon personalities. One account, which was quickly banned, had attempted to use the likeness of YouTube star Tyler Toney from Dude Perfect.[85] In April 2021, The Intercept reported on Amazon's planned internal messaging app that would ban words like "union", "living wage", "freedom", "pay raise" or "restrooms".[86][87]

In April 2022, Amazon workers in Staten Island voted to form Amazon Labor Union, the company's first legally recognized union.[88][89][90] In August 2022, workers in an Albany, New York, location filed a petition for an election in an attempt to become what would be the fourth unionized warehouse at the time.[91]

Wages

Throughout the summer of 2018, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders criticized Amazon's wages and working conditions in a series of YouTube videos and media appearances. He also pointed to the fact that Amazon had paid no federal income tax in the previous year.[92] Sanders solicited stories from Amazon warehouse workers who felt exploited by the company.[93] One such story, by James Bloodworth, described the environment as akin to "a low-security prison" and stated that the company's culture used an Orwellian newspeak.[94] These reports cited a finding by New Food Economy that one third of fulfilment center workers in Arizona were on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).[95] Responses by Amazon included incentives for employees to tweet positive stories and a statement which called the salary figures used by Sanders "inaccurate and misleading". The statement also charged that it was inappropriate for him to refer to SNAP as "food stamps".[93] On September 5, 2018, Sanders along with Ro Khanna introduced the Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies (Stop BEZOS) Act aimed at Amazon and other alleged beneficiaries of corporate welfare such as Walmart, McDonald's and Uber.[96] Among the bill's supporters were Tucker Carlson of Fox News and Matt Taibbi who criticized himself and other journalists for not covering Amazon's contribution to wealth inequality earlier.[97][98]

On October 2, 2018, Amazon announced that its minimum wage for all American employees would be raised to $15 per hour. Sanders congratulated the company for making this decision.[99]

Worker conditions

Former employees, current employees, the media, and politicians have criticized Amazon for poor working conditions at the company.[100][101][102] In 2011, it was publicized that workers had to carry out tasks in 100 °F (38 °C) heat at the Breinigsville, Pennsylvania warehouse. As a result of these conditions, employees became extremely uncomfortable and suffered from dehydration and collapse. Loading-bay doors were not opened to allow in fresh air because of concerns over theft.[103] Amazon's initial response was to pay for an ambulance to sit outside on call to cart away overheated employees.[103] The company eventually installed air conditioning at the warehouse.[104]

Some workers, "pickers", who travel the building with a trolley and a handheld scanner "picking" customer orders, can walk up to 15 miles (24 km) during their workday and if they fall behind on their targets, they can be reprimanded. The handheld scanners give real-time information to the employee on how quickly or slowly they are working; the scanners also serve to allow Team Leads and Area Managers to track the specific locations of employees and how much "idle time" they gain when not working.[105][106]

In a German television report broadcast in February 2013, journalists Diana Löbl and Peter Onneken conducted a covert investigation at the distribution center of Amazon in the town of Bad Hersfeld in the German state of Hessen. The report highlights the behavior of some of the security guards, themselves being employed by a third-party company, who apparently either had a neo-Nazi background or deliberately dressed in neo-Nazi apparel and who were intimidating foreign and temporary female workers at its distribution centers. The third-party security company involved was delisted by Amazon as a business contact shortly after that report.[107][108][109][110]

In March 2015, it was reported in The Verge that Amazon would be removing non-compete clauses of 18 months in length from its US employment contracts for hourly-paid workers, after criticism that it was acting unreasonably in preventing such employees from finding other work. Even short-term temporary workers have to sign contracts that prohibit them from working at any company where they would "directly or indirectly" support any good or service that competes with those they helped support at Amazon, for 18 months after leaving Amazon, even if they are fired or made redundant.[111][112]

A 2015 front-page article in The New York Times profiled several former Amazon employees[113] who together described a "bruising" workplace culture in which workers with illness or other personal crises were pushed out or unfairly evaluated.[114] Bezos responded by writing a Sunday memo to employees,[115] in which he disputed the Times's account of "shockingly callous management practices" that he said would never be tolerated at the company.[114]

To boost employee morale, on November 2, 2015, Amazon announced that it would be extending six weeks of paid leave for new mothers and fathers. This change includes birth parents and adoptive parents and can be applied in conjunction with existing maternity leave and medical leave for new mothers.[116]

In mid-2018, investigations by journalists and media outlets such as The Guardian reported poor working conditions at Amazon's fulfillment centers.[117][118] Later in 2018, another article exposed poor working conditions for Amazon's delivery drivers.[119] In response to criticism that Amazon does not pay its workers a livable wage, Jeff Bezos announced beginning November 1, 2018, all US and UK Amazon employees will earn a $15 an hour minimum wage.[120] Amazon will also lobby to make $15 an hour the federal minimum wage.[121] At the same time, Amazon also eliminated stock awards and bonuses for hourly employees.[122]

A September 11, 2018, article exposed poor working conditions for Amazon's delivery drivers, describing a variety of alleged abuses, including missing wages, lack of overtime pay, favoritism, intimidation, and time constraints that forced them to drive at dangerous speeds and skip meals and bathroom breaks.[123] Amazon uses Netradyne artificial intelligence cameras in some partner vans to monitor safety incidents and driver behaviour, drawing criticism from some drivers.[124]

On Black Friday 2018, Amazon warehouse workers in several European countries, including Italy, Germany, Spain, and the United Kingdom, went on strike to protest inhumane working conditions and low pay.[125]

The Daily Beast reported in March 2019 that emergency services responded to 189 calls from 46 Amazon warehouses in 17 states between the years 2013 and 2018, all relating to suicidal employees. The workers attributed their mental breakdowns to employer-imposed social isolation, aggressive surveillance, and the hurried and dangerous working conditions at these fulfillment centers. One former employee told The Daily Beast "It's this isolating colony of hell where people having breakdowns is a regular occurrence."[126]

On July 15, 2019, during the onset of Amazon's Prime Day sale event, Amazon employees working in the United States and Germany went on strike in protest of unfair wages and poor working conditions.[127][128]

In August 2019, the BBC reported on Amazon's Twitter ambassadors. Their constant support for and defense of Amazon and its practices have led many Twitter users to suspect that they are in fact bots, being used to dismiss the issues affecting Amazon workers.[129] In March 2021, a flurry of new ambassador accounts claiming to be employees defended the company against a unionization drive, in some cases making the false claim that there was no way to opt-out of union dues. Amazon confirmed at least one was fake, and Twitter shut down several for violating its terms of use.[130]

In November 2019, NBC reported some contracted Amazon locations, against company policy, allowed people to make deliveries using other people's badges and passwords in order to circumvent employee background checks and avoid financial penalties or termination due to sub-standard performance. Amazon's performance quotas were criticized as unrealistic and as pressuring drivers to speed, run stop signs, carry overloaded vehicles, and urinate in bottles due to lack of time for bathroom stops; the company was generally able to avoid legal liability for resulting vehicle crashes by using independent contractors.[131]

In March 2020, during the coronavirus outbreak when the government instructed companies to restrict social contact, Amazon's UK staff was forced to work overtime to meet the demand spiked by the disease. A GMB spokesperson said the company had put "profit before safety".[132] GMB has continued to raise concerns regarding "gruelling conditions, unrealistic productivity targets, surveillance, bogus self-employment and a refusal to recognise or engage with unions unless forced", calling for the UK government and safety regulators to take action to address these issues.[133]

In its 2020 statement to its US shareholders, Amazon stated that "we respect and support the Core Conventions of the International Labour Organization (ILO), the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, and the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights". Operation of these Global Human Rights Principles has been "long-held at Amazon, and codifying them demonstrates our support for fundamental human rights and the dignity of workers everywhere we operate".[134]

In June 2020, subcontracted delivery drivers based in Canada launched a class action lawsuit against Amazon Canada, claiming that $200 million in unpaid wages were owed to them because Amazon retained "effective control" over their work and should therefore legally be considered their employer.[135]

On November 27, 2020, Amnesty International said, workers working for Amazon have faced great health and safety risks since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. On Black Friday, one of Amazon's busiest periods, the company failed to ensure key safety features in France, Poland, the United Kingdom, and USA. Workers have been risking their health and lives to ensure essential goods are delivered to consumer doorsteps, helping Amazon achieve record profits.[136]

On January 6, 2021, Amazon said that it is planning to build 20,000 affordable houses by spending $2 billion in the regions where the major employments are located.[137]

On January 24, 2021, Amazon said that it was planning to open a pop-up clinic hosted in partnership with Virginia Mason Franciscan Health in Seattle in order to vaccinate 2,000 persons against COVID-19 on the first day.[138]

In February 2021, Amazon said that it was planning to put cameras in its delivery vehicles. Although many drivers were upset by this decision, Amazon said that the videos would only be sent in certain circumstances.[139]

Drivers have alleged they sometimes have to urinate and defecate in their vans as a result of pressure to meet quotas. This was denied in a tweet from the official Amazon News account saying: "You don't really believe the peeing in bottles thing, do you? If that were true, nobody would work for us." Amazon employees subsequently leaked an email to The Intercept[140] showing the company was aware its drivers were doing so. The email said: "This evening, an associate discovered human feces in an Amazon bag that was returned to station by a driver. This is the 3rd occasion in the last 2 months when bags have been returned to the station with poop inside."[141] Amazon acknowledged the issue publicly after denying it at first.[142]

A June 2021 analysis of OSHA data by The Washington Post found Amazon warehouse jobs "can be more dangerous than at comparable warehouses."[143]

In July 2021, workers at the warehouse in New York City filed a complaint with the Occupational Safety and Health Administration which describes harsh 12-hour workdays with sweltering internal temperatures that resulted in fainting workers being carried out on stretchers. The complaint reads "internal temperature is too hot. We have no ventilation, dusty, dirty fans that spread debris into our lungs and eyes, are working at a non-stop pace and [we] are fainting out from heat exhaustion, getting nose bleeds from high blood pressure, and feeling dizzy and nauseous." They add that many of the fans provided by the company don't work, water fountains often lack water, and cooling systems are insufficient. Those filing the complaint are affiliated with the Amazon Labor Union group attempting to unionize the facility, which the company has been actively campaigning against. Similar conditions have been reported elsewhere, such as in Kent, Washington during the 2021 heat wave.[144][145]

A 2021 report by the National Employment Law Project found that working conditions at Amazon fulfillment centers in Minnesota are dangerous and unsustainable, with more than double the rate of injuries compared to non-Amazon warehouses for the years 2018 to 2020.[146]

In December 2021, after a tornado destroyed an Amazon warehouse in Illinois, the company and its policies were criticized on several fronts: making people work during an imminent tornado,[147] cell phone ban preventing access to emergency alerts,[148] and company founder Jeff Bezos' apparent insensitivity to the fatal catastrophe as he celebrated his space company's latest achievement and only belatedly acknowledged the loss of life.[149][150]

2018 workers strike

Spanish unions called on 1,000 Amazon workers to strike starting on July 10 and lasted through Amazon Prime Day, with calls for the strike to be seen all across the world, and for customers to follow suit.[151] The strike based in Spain was timed around Prime Day, with a representative of the Comisiones Obreras (CCOO) union said complaints were based on wage cuts, working conditions, and restrictions on time off.[152] However, other European countries have other raised grievances, with Poland, Germany, Italy, Spain, England, and France all being represented and shown below.[153]

- Poland workers claim an anti-strike law has made it impossible to negotiate a better salary.

- German workers have been fighting for over two years for a collective bargaining agreement.

- Italian workers have highlighted claims that Amazon routinely hires contract workers who aren't required to have benefits.

- Spanish Amazon leaders have unilaterally imposed working conditions when previous collective bargaining agreements had expired.

- English and French Amazon leaders have imposed demanding measures on time and efficiency leading to workers expected to process 300 items per hour and urinate in bottles, with penalties being given for sick days and pregnancies.

Stop BEZOS Act

On September 5, 2018, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Representative Ro Khanna (D-CA-17) introduced the Stop Bad Employers by Zeroing Out Subsidies (Stop BEZOS) Act aimed at Amazon and other alleged beneficiaries of corporate welfare such as Walmart, McDonald's, and Uber.[154] This followed several media appearances in which Sanders underscored the need for legislation to ensure that Amazon workers received a living wage.[155][156] These reports cited a finding by New Food Economy that one third of fulfilment center workers in Arizona were on the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).[157] Although Amazon initially released a statement which called statistics such as this "inaccurate and misleading", an October 2 announcement affirmed that its minimum wage for all employees would be raised to $15 per hour.[158]

Racial discrimination

In 2021, current and former corporate workers, including Chanin Kelly-Rae, former diversity lead, went public about alleged systemic discrimination against women and people of color at the company.[159] Also in 2021, multiple Black employees filed discrimination lawsuits against the company.[160]

In 2019, black software engineer Nadia Odunayo created The StoryGraph, which has since become the main competitor and rival of Amazon's subsidiary Goodreads. In contrast to Goodreads, which is a largely white-owned and white-managed company, Odunayo's The StoryGraph is owned and designed by a woman of color and remedied many of the issues that users complained about with Goodreads.[161][162][163][164] Amazon and Goodreads have never publicly responded to The StoryGraph's existence, and have largely left the platform alone.

Response to the COVID-19 pandemic

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Amazon introduced a hazard pay of $2-per-hour, changes to overtime pay, and a policy of unlimited, unpaid time off until April 30, 2020. The hazard pay increase expired in June 2020, and the paid time-off policy in May 2022.[165][166] Amazon also introduced temporary restrictions on the sale of non-essential goods, and hired 100,000 more staff in the US and Canada.[167] Some Amazon workers in the US, France, and Italy protested the company's decision to "run normal shifts" despite many positive COVID-19 cases.[168][169] In Spain, the company has faced legal complaints over its policies.[170] A group of US Senators wrote an open letter to Bezos in March 2020, expressing concerns about worker safety.[171]

An Amazon warehouse protest on March 30, 2020, in Staten Island led to its organizer, Christian Smalls, being fired. Amazon defended the decision by saying that Smalls was supposed to be in self-isolation at the time and leading the protest put its other workers at risk.[170] Smalls has called this response "ridiculous".[172] The New York state attorney general, Letitia James, is considering legal retaliation to the firing which she called "immoral and inhumane."[170] She also asked the National Labor Relations Board to investigate Smalls' firing. Smalls himself accuses the company of retaliating against him for organizing a protest.[172] At the Staten Island warehouse, one case of COVID-19 has been confirmed by Amazon; workers believe there are more, and say that the company has not cleaned the building, given them suitable protection, or informed them of potential cases.[171] Smalls added specifically that there are many workers there in risk categories, and the protest only demanded that the building be sanitized and the employees continue to be paid during that process.[172] Derrick Palmer, another worker at the Staten Island facility, told The Verge that Amazon quickly communicates through text and email when they need the staff to complete mandatory overtime, but have not been using this to tell people when a colleague has contracted the disease, instead of waiting days and sending managers to speak to employees in person.[171] Amazon claim that the Staten Island protest only attracted 15 of the facility's 5,000 workers,[173] while other sources describe much larger crowds.[171]

On April 14, 2020, two Amazon employees were fired for "repeatedly violating internal policies", after they had circulated a petition about health risks for warehouse workers internally.[174]

On May 4, Amazon vice president Tim Bray resigned "in dismay" over the firing of whistle-blower employees who spoke out about the lack of COVID-19 protections, including shortages of face masks and failure to implement widespread temperature checks which were promised by the company. He said that the firings were "chickenshit" and "designed to create a climate of fear" in Amazon warehouses.[175]

In a Q1 2020 financial report, Jeff Bezos announced that Amazon expects to spend $4 billion or more (predicted operating profit for Q2) on COVID-19-related issues: personal protective equipment, higher wages for hourly teams, cleaning for facilities, and expanding Amazon's COVID-19 testing capabilities. These measures intend to improve the safety and well-being of hundreds of thousands of the company's employees.[176]

From the beginning of 2020 until September of the same year, the company declared that the total number of workers who had contracted the infection was 19,816.[177]

Closure in France

The SUD (trade unions) brought a court case against Amazon for unsafe working conditions. This resulted in a French district court (Nanterre) ruling on April 15, 2020, ordering the company to limit, under threat of a €1 million per day fine, its deliveries to certain essential items, including electronics, food, medical or hygienic products, and supplies for home improvement, animals, and offices.[178] Instead, Amazon immediately shut down its six warehouses in France, continuing to pay workers but limiting deliveries to items shipped from third-party sellers and warehouses outside of France.[179] The company said the €100,000 fine for each prohibited item shipped could result in billions of dollars in fines even with a small fraction of items misclassified.[180] After losing an appeal and coming to an agreement with labor unions for more pay and staggered schedules, the company reopened its French warehouses on May 19.[179]

Matt Walsh books

Conservative political commentator Matt Walsh has published various books, some of which were deemed transphobic, including a children's book titled Johnny the Walrus (an allegorical tale about a boy whose parents surgically transition him into a walrus after catching him pretending to be one). A number of these books became bestsellers on Amazon, annoying and upsetting numerous Amazon employees, who claimed to have been traumatized by the books being sold on Amazon. Amazon held a session for the employees to discuss their trauma, while other employees hosted a "die-in" protest, arguing that transphobic opinions in the media contributed to hate speech, suicide of trans youth, and misconceptions about trans people.[181][182][183][184] Matt Walsh, in turn, took the reaction of the Amazon employees as a point of amusement, noting that Johnny the Walrus had been listed on Amazon as the #1 Bestselling "LGBT" book (the book was later moved to a political genre category), while some Amazon employees argued that books that promote "transphobia" should be outright banned entirely from Amazon's platforms.[185][186][187]

Employee dissent

In 2014, a former Amazon employee Kivin Varghese went on a hunger strike to change Amazon's unfair policies.[188] In November 2016, an Amazon employee jumped from the roof of the company's headquarters office as a result of unfair treatment at work.[189]

In 2020, Tim Bray, Vice President at AWS at the time, resigned in protest of Amazon's treatment of its activist employees involved with AECJ who led a public agitation against unhealthy working conditions in Amazon's warehouses during the COVID-19 pandemic.[190]

In April 2022, The Intercept reported that Amazon's planned internal messaging app would ban words like "union", "living wage", "freedom", "pay raise" or "restrooms" which could potentially indicate worker unhappiness.[191][192]

Forced labor in China

Amazon is one of the companies "potentially directly or indirectly benefiting" from forced Uighur labor according to a report by Australian Strategic Policy Institute, a think tank partly funded by the US Department of Defense.[193]

Treatment of customers

Differential pricing

In September 2000, price discrimination potentially violating the Robinson–Patman Act was found on amazon.com. Amazon offered to sell a buyer a DVD for one price, but after the buyer deleted cookies that identified him as a regular Amazon customer, he was offered the same DVD for a substantially lower price.[194] Jeff Bezos subsequently apologized for the differential pricing and vowed that Amazon "never will test prices based on customer demographics". The company said the difference was the result of a random price test and offered to refund customers who paid the higher prices.[195] Amazon had also experimented with random price tests in 2000 as customers comparing prices on a "bargain-hunter" website discovered that Amazon was randomly offering the Diamond Rio MP3 player for substantially less than its regular price.[196]

Kindle content removal

In July 2009, The New York Times reported that amazon.com deleted all customer copies of certain books published in violation of US copyright laws by MobileReference,[197] including the books Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm from users' Kindles. This action was taken with neither prior notification nor specific permission of individual users. Customers did receive a refund of the purchase price and, later, an offer of an Amazon gift certificate or a check for $30. The e-books were initially published by MobileReference on Mobipocket for sale in Australia only—owing to those works having fallen into public domain in Australia. However, when the e-books were automatically uploaded to Amazon by MobiPocket, the territorial restriction was not honored, and the book was allowed to be sold in territories such as the United States where the copyright term had not expired.

Author Selena Kitt fell victim to Amazon content removal in December 2010; some of her fiction had described incest. Amazon claimed "Due to a technical issue, for a short window of time three books were temporarily unavailable for re-download by customers who had previously purchased them. When this was brought to our attention, we fixed the problem..." in an attempt to defuse user complaints about the deletions.[198]

Late in 2013, online blog The Kernel released multiple articles revealing "an epidemic of filth" on Amazon and other e-book storefronts. Amazon responded by blocking books dealing with incest, bestiality, child pornography as well as topics such as virginity, monsters, and barely-legal.[199][200]

Sale of Wikipedia's material as books

The German-speaking press and blogosphere have criticized Amazon for selling tens of thousands of print on demand books which reproduced Wikipedia articles.[201][202][203][204] These books are produced by an American company named Books LLC and by three Mauritian subsidiaries of the German publisher VDM: Alphascript Publishing, Betascript Publishing and Fastbook Publishing. Amazon did not acknowledge this issue raised on blogs and some customers that have asked the company to withdraw all these titles from its catalog.[202] The collaboration between amazon.com and VDM Publishing began in 2007.[205]

Product substitution

The British consumer organization Which? has published information about Amazon Marketplace in the UK which indicates that when small electrical products are sold on Marketplace the delivered product may not be the same as the product advertised.[206] A test purchase is described in which eleven orders were placed with different suppliers via a single listing. Only one of the suppliers delivered the actual product displayed, two others delivered different, but functionally equivalent products and eight suppliers delivered products that were quite different and not capable of safely providing the advertised function. The Which? article also describes how the customer reviews of the product are actually a mix of reviews for all of the different products delivered, with no way to identify which product comes from which supplier. This issue was raised in evidence to the UK Parliament in connection with a new Consumer Rights bill.[207]

Items added onto baby registries

In 2018 it was reported that Amazon has been selling sponsored ads pretending to be items on a baby registry. The ads looked very similar to the actual items on the list.[208]

Third-party sellers

A 2019 Wall Street Journal (WSJ) investigation found third-party retailers selling over 4,000 unsafe, banned, or deceptively labeled products on Amazon.com. According to the WSJ article, when customers have sued Amazon for unsafe products sold by third-party sellers on Amazon.com, Amazon's legal defense has been that it is not the seller and therefore cannot be held liable.[209] Wirecutter reported in 2020 that over several months they "were able to purchase items through Amazon Prime that were either confirmed counterfeits, lookalikes unsafe for use, or otherwise misrepresented."[210] CNBC reported in 2019 that Amazon third-party sellers regularly sell expired food products, and that the sheer size of the Amazon Marketplace has made policing the platform exceptionally difficult for the company.[211]

As of 2020[update], third-party sellers accounted for 54% of paid units sold on Amazon platforms.[212] In 2019, Amazon earned $54 billion from the fees third-party retailers pay to Amazon for seller services.[213]

De-platforming WikiLeaks

On December 1, 2010, Amazon stopped hosting the website associated with the whistle-blowing organization WikiLeaks. Amazon did not initially comment on whether it forced the site to leave.[214] The New York Times reported: "Senator Joseph I. Lieberman, an independent of Connecticut, said Amazon had stopped hosting the WikiLeaks site on Wednesday after being contacted by the staff of the Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee".[215]

In a later press release issued by Amazon, they denied that they had terminated Wikileaks.org because of either "a government inquiry" or "massive DDOS attacks". They claimed that it was because of "a violation of [Amazon's] terms of service" because Wikileaks.org was "securing and storing large quantities of data that isn't rightfully theirs, and publishing this data without ensuring it won't injure others."[216]

According to WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, this demonstrated that Amazon (a US based company) was in a jurisdiction that "suffered a free speech deficit".[217]

Amazon's action led to a public letter from Daniel Ellsberg, famous for leaking the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam war. Ellsberg stated that he was "disgusted by Amazon's cowardice and servility", likening it to "China's control of information and deterrence of whistle-blowing", and he called for a "broad" and "immediate" boycott of Amazon.[218]

Users privacy

The release of the Amazon Echo was met with concerns about Amazon releasing customer data at the behest of government authorities. According to Amazon, voice recordings of customer interactions with the assistant are stored with the possibility of being released later in the event of a warrant or subpoena.[219] A police request for such data occurred during the investigation into the November 22, 2015, death of Victor Collins in the home of James Andrew Bates in Bentonville, Arkansas.[220][221] Amazon refused to comply at first, but Bates later consented.[222][223]

While Amazon has publicly opposed secret government surveillance, as revealed by Freedom of Information Act requests it has supplied facial recognition support to law enforcement in the form of the Rekognition technology and consulting services. Initial testing included the city of Orlando, Florida, and Washington County, Oregon. Amazon offered to connect Washington County with other Amazon government customers interested in Rekognition and a body camera manufacturer. These ventures are opposed by a coalition of civil rights groups with concern that they could lead to expansion of surveillance and be prone to abuse. Specifically, it could automate the identification and tracking of anyone, particularly in the context of potential police body camera integration.[224][225][226] Due to the backlash, the city of Orlando publicly stated it will no longer use the technology, but may revisit this decision at a later date.[227]

On February 17, 2020, a Panorama documentary broadcast by the BBC in the UK highlighted the amount of data collected by the company and the move into surveillance causing concerns of politicians and regulators in the US and Europe.[228][229]

On July 16, 2021, the Luxembourg National Commission for Data Protection fined Amazon Europe Core S.à.r.l.[note 1] a record €746 million ($888 million) for processing personal data in violation of the EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).[230] The fine represented about 4.2 percent of Amazon's reported $21.3 billion income for 2020.[231] It is the largest fine ever imposed for a violation of the GDPR.[232] Amazon has announced it will appeal the decision.[233]

Competitive advantages

Tax avoidance

Amazon's tax affairs were investigated in China, Germany, Poland, South Korea, France, Japan, Ireland, Singapore, Luxembourg, Italy, Spain, United Kingdom, United States, and Portugal.[234] A report released by Fair Tax Mark in 2019, labelled Amazon the "worst" offender for tax avoidance, having paid a 12% effective tax rate between 2010 and 2018, in contrast with 35% corporate tax rate in the US during the same period. Amazon countered that it had a 24% effective tax rate during the same period.[235]

Effects on small businesses

Due to its size and economies of scale, Amazon is able to out price local small-scale shopkeepers.[236] Stacy Mitchell and Olivia Lavecchia, researchers with the Institute for Local Self-Reliance, argue that this has caused most local small-scale shopkeepers to close down in a number of cities and towns in the United States. Additionally, a merchant cannot have an item in the warehouse available to sell prior to Amazon if they choose to list it as well. Many times fraudulent charges have been made on the company banking and financial channels without approval, since Amazon prides itself on keeping all financial data permanently on file in their database.[relevant?] If they charge your account they will not refund the money back to the account they took it from, they will only provide an Amazon credit.[relevant?] Additionally, there is not any merchant customer support which at times needs to be handled in real-time.[relevant?][237]

U.S. Post Office deal

In early 2018, President Donald Trump repeatedly criticized Amazon's use of the United States Postal Service and its prices for the delivery of packages, stating, "I am right about Amazon costing the United States Post Office massive amounts of money for being their Delivery Boy," Trump tweeted. "Amazon should pay these costs (plus) and not have them bourne [sic] by the American Taxpayer."[238] Amazon's shares fell by 6 percent as a result of Trump's comments. Shepard Smith of Fox News disputed Trump's claims and pointed to evidence that the USPS was offering below-market prices to all customers with no advantage to Amazon. However, analyst Tom Forte pointed to the fact that Amazon's payments to the USPS are not made public and that their contract has a reputation for being "a sweetheart deal".[239][240]

HQ2 bidding war

The announcement of Amazon's plan to build a second headquarters, dubbed HQ2, was met with 238 proposals, 20 of which became finalist cities on January 18, 2018.[241] In November 2018, Amazon was criticized for narrowing this down to "the two richest cities", namely Long Island City and Arlington, Virginia, which are in the New York metropolitan area and Washington metropolitan area respectively.[242] Critics, including business professor Scott Galloway, described the bidding war as "a con" and stated that it was a pretext for gaining tax breaks and insider information for the company.[243][244]

Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez opposed the $1.5 billion in tax subsidies that had been given to Amazon as part of the deal. She stated that restoring the subway system would be a better use for the money, despite rebuttals from Andrew Cuomo and others that New York would benefit economically.[245] Shortly afterward, Politico reported that 1,500 affordable homes had previously been slated for the land being occupied by Amazon's new office.[246] The request by Amazon executives for a helipad at each location proved especially controversial with multiple New York City Council members decrying the proposal as frivolous.[247]

Governments

CIA and Washington Post conflict of interest

In 2013, Amazon secured a US$600 million contract with the CIA, which has been described as a potential conflict of interest involving the Bezos-owned The Washington Post and his newspaper's coverage of the CIA.[248][249] This was later followed by a bid for a US$10 billion contract with the Department of Defense. Although critics initially considered the government's preference for Amazon to be a foregone conclusion, the contract was ultimately signed with Microsoft.[250][251]

Government-ordered censorship

Amazon stated of being “committed to diversity, equity and inclusion”, but it was seen obliging to the censorship demands of several countries.[252] In 2021, the Chinese website of Amazon complied to an order of the Chinese government, and removed the customer reviews and ratings for a book written on Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping’s speeches and writings. Besides, the comments section was also disabled.[253] In 2022, the company obliged to the UAE government’s demand and restricted the LGBTQ products on its Emirati website. Documents revealed that under the threat of unknown penalties, Amazon removed searches on over 150 keywords related to LGBTQ products. Moreover, a number of book titles were also blocked, including My Lesbian Experience With Loneliness by Nagata Kabi, Gender Queer: A Memoir by Maia Kobabe, and Bad Feminist by Roxane Gay.[254][255] Amazon said they were restricted to “comply with the local laws and regulations of the countries in which we operate”.[252]

Israeli military contract

Project Nimbus, a $1.2 billion deal in which the technology companies Amazon and Google will provide Israel and its military with artificial intelligence, machine learning, and other cloud computing services, including building local cloud sites that will "keep information within Israel's borders under strict security guidelines."[256][257][258] The contract has drawn rebuke and condemnation from the companies' shareholders as well as their employees, over concerns that the project may lead to abuses of Palestinians' human rights in the context of the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict.[259][260] Specifically, they voice concern over how the technology will enable further surveillance of Palestinians and unlawful data collection on them as well as facilitate the expansion of illegal Israeli settlements.[260]

NHS non-patient healthcare data

The UK government awarded Amazon a contract that gives the company access to healthcare information published by the UK's National Health Service.[261] This will, for example, be used by Amazon's Alexa to answer medical questions, although Alexa also uses many other sources of information. The material, which excludes patient data, could also allow the company to make, advertise and sell its products. The contract allows Amazon access to information on symptoms, causes, and definitions of conditions, and "all related copyrightable content and data and other materials". Amazon can then create "new products, applications, cloud-based services and/or distributed software", which the NHS will not benefit from financially. The company can also share the information with third parties. The government said that allowing Alexa devices to offer expert health advice to users will reduce pressure on doctors and pharmacists.[262]

Seattle head tax and houselessness services

In May 2018, Amazon threatened the Seattle City Council over an employee head tax proposal that would have funded houselessness services and low-income housing. The tax would have cost Amazon about $800 per employee, or 0.7% of their average salary.[263] In retaliation, Amazon paused construction on a new building, threatened to limit further investment in the city, and funded a repeal campaign. Although originally passed, the measure was soon repealed after an expensive repeal campaign spearheaded by Amazon.[264]

Tennessee expansion

The incentives given by the Metropolitan Council of Nashville and Davidson County to Amazon for their new Operations Center of Excellence in Nashville Yards, a site owned by developer Southwest Value Partners, have been controversial, including the decision by the Tennessee Department of Economic and Community Development to keep the full extent of the agreement secret.[265] The incentives include "$102 million in combined grants and tax credits for a scaled-down Amazon office building" as well as "a $65 million cash grant for capital expenditures" in exchange for the creation of 5,000 jobs over seven years.[265]

The Tennessee Coalition for Open Government called for more transparency.[265] Another local organization known as the People's Alliance for Transit, Housing, and Employment (PATHE) suggested no public money should be given to Amazon; instead, it should be spent on building more public housing for the working poor and the homeless and investing in more public transportation for Nashvillians.[266] Others suggested incentives to big corporations do not improve the local economy.[267]

In November 2018, the proposal to give Amazon $15 million in incentives was criticized by the Nashville Firefighters Union and the Nashville chapter of the Fraternal Order of Police,[268] who called it "corporate welfare."[269] In February 2019, another $15.2 million in infrastructure was approved by the council, although it was voted down by three council members, including Councilwoman Angie Henderson who dismissed it as "cronyism".[270]

Product availability

Animal cruelty

Amazon at one time carried two cockfighting magazines and two dog fighting videos although the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) contends that the sale of these materials is a violation of U.S. Federal law and filed a lawsuit against Amazon.[271] A campaign to boycott Amazon in August 2007 gained attention after a dog fighting case involving NFL quarterback Michael Vick.[272] In May 2008, Marburger Publishing agreed to settle with the Humane Society by requesting that Amazon stop selling their magazine, The Game Cock. The second magazine named in the lawsuit, The Feathered Warrior, remained available.[273]

Animal rights group Mercy for Animals has alleged that Amazon allows the listing of foie gras on its website, a product that has been banned in several countries followed by California, and alleged to be produced by the mistreatment of ducks. The listing promoted animal rights groups to launch a movement called "Amazon cruelty".[274][275]

Items prohibited by UK law

In December 2015 The Guardian newspaper published an exposé of sales that violated British law.[276] These included a pepper-spray gun (sold directly by amazon.co.uk), acid, stun guns and a concealed cutting weapon (sold by Amazon Marketplace traders). All are classed as prohibited weapons in the UK. At the same time, The Guardian published a video describing some of the weapons.[277]

Likewise, brass catchers, illegal in New South Wales, are sold by Amazon.com.au.

Antisemitic content

An article published in the Czech weekly Tyden in January 2008 called attention to shirts sold by Amazon which were emblazoned with "I Love Heinrich Himmler" and "I Love Reinhard Heydrich", professing affection for the infamous Nazi officers and war criminals. Patricia Smith, a spokeswoman for Amazon, told Tyden, "Our catalog contains millions of items. With such a large number, unexpected merchandise may get onto the Web." Smith told Tyden that Amazon does not intend to stop cooperating with Direct Collection, the producer of the T-shirts. Following pressure from the World Jewish Congress (WJC), Amazon announced that it had removed from its website the aforementioned T-shirts as well as "I love Hitler" T-shirts that they were selling for women and children.[278] After the WJC intervention, other items such as a Hitler Youth Knife emblazoned with the Nazi slogan "Blood and Honor" were also removed from Amazon.com as well as a 1933 German SS Officer Dagger distributed by Knife-Kingdom.[279]

An October 2013 report in the British online magazine The Kernel revealed that Amazon.com was selling books that defend Holocaust denial, and shipped them even to customers in countries where Holocaust denial is prohibited by law.[280]

That month, the WJC called on Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos to remove from its offer books that deny the Holocaust and promote antisemitism, white supremacy, racism or sexism. "No one should profit from the sale of such vile and offensive hate literature. Many Holocaust survivors are deeply offended by the fact that the world's largest online retailer is making money from selling such material," WJC Executive Vice President Robert Singer wrote in a letter to Bezos.[281][282]

Although Nazi paraphernalia was still listed on Amazon in the US and Canada in 2016,[283] on March 9, 2017, the WJC announced Amazon's compliance with the requests it and other Jewish organizations had submitted by removing from sale the Holocaust denial works complained of in the requests. The WJC offered ongoing assistance in identifying Holocaust denial works among Amazon's offerings in the future.[284]

In July 2019, the Central Council of Jews in Germany denounced Amazon for continuing to sell items that glorify the Nazis. In December 2019, Amazon was caught selling Auschwitz-themed Christmas tree ornaments on its platform, printed on demand with stock images of the concentration camp from a third-party seller; Amazon eventually removed the ornaments from all platforms. Auschwitz Memorial, the group responsible for maintaining the concentration camp for historical and educational purposes, then stated that it had found a "disturbing online product from another seller – a computer mouse-pad bearing the image of a freight train used for deporting people to the concentration camps."[285] Louise Matsakis, a journalist for Wired, called the Holocaust-themed products "the byproduct of an increasingly automated e-commerce landscape", noting that the items were print-on-demand and that Amazon only became aware of them after customers had reported the offending items.[286]

In late 2020, Amazon removed all new and used print and digital copies of The Turner Diaries, an antisemitic and racist dystopian fiction novel, from its bookselling platform, including all subsidiaries (AbeBooks, The Book Depository), effectively stopping sales of the title from the digital bookselling market. Amazon listed the title's connection with the QAnon movement as the reason behind this, having already purged a number of self-published and small-press titles connected with QAnon from its platform.[287] Social cataloguing and book review website Goodreads, another subsidiary of Amazon, also purged the metadata from its record for all editions of The Turner Diaries, replacing the author and title field with "NOT A BOOK" (capitalization intended), a designated moniker normally used by the platform to weed non-book items with ISBN numbers, as well as plagiarized titles, from its catalogue.[288]

Pedophile guide

On November 10, 2010, a controversy arose over the sale by Amazon of an e-book by Phillip R. Greaves entitled The Pedophile's Guide to Love and Pleasure: A Child-lover's Code of Conduct.[289]

Readers threatened to boycott Amazon over its selling of the book, which was described by critics as a "pedophile guide". Amazon initially defended the sale of the book, saying that the site "believes it is censorship not to sell certain books simply because we or others believe their message is objectionable"[290] and that the site "supported the right of every individual to make their own purchasing decisions". However, the site later removed the book.[291] The San Francisco Chronicle wrote that Amazon "defended the book, then removed it, then reinstated it, and then removed it again".[290]

Christopher Finan, the president of the American Booksellers Foundation for Free Expression, argued that Amazon has the right to sell the book as it is not child pornography or legally obscene since it does not have pictures. On the other hand, Enough Is Enough, a child safety organization, issued a statement saying that the book should be removed and that it "lends the impression that child abuse is normal".[292] People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), citing the removal of The Pedophile's Guide from Amazon, urged the website to also remove books on dog fighting from its catalogue.[293]

Greaves was arrested on December 20, 2010, at his Pueblo, Colorado home on a felony warrant issued by the Polk County Sheriff's Office in Lakeland, Florida. Detectives from the county's Internet Crimes Division ordered a signed hard copy version of Greaves' book and had it shipped to the agency's jurisdiction, where it violated state obscenity laws. According to Sheriff Grady Judd, upon receipt of the book, Greaves violated local laws prohibiting the distribution of "obscene material depicting minors engaged in harmful conduct", a third-degree felony.[294] Greaves pleaded no contest to the charges and was later released under probation with his previous jail time counting as time served.[295]

Counterfeit products

On October 16, 2016, Apple filed a trademark infringement case against Mobile Star LLC for selling counterfeit Apple products to Amazon. In the suit, Apple provided evidence that Amazon was selling these counterfeit Apple products and advertising them as genuine. Through purchasing, Apple found that it was able to identify counterfeit products with a success rate of 90%. Amazon was sourcing and selling items without properly determining if they are genuine. Mobile Star LLC settled with Apple for an undisclosed amount on April 27, 2017.[296]

In the following years, the selling of counterfeit products by Amazon has attracted widespread notice, with both purchases marked as being fulfilled by third parties and those shipped directly from Amazon warehouses being found to be counterfeit.[297] This has included some products sold directly by Amazon itself and marked as "ships from and sold by Amazon.com".[298] Counterfeit charging cables sold on Amazon as purported Apple products have been found to be a fire hazard.[299][300] Such counterfeits have included a wide array of products, from big ticket items to every day items such as tweezers, gloves,[301] and umbrellas.[302] More recently, this has spread to Amazon's newer grocery services.[303] Counterfeiting was reported to be especially a problem for artists and small businesses whose products were being rapidly copied for sale on the site.[304] As a result of these issues, companies such as Birkenstocks and Nike have pulled their products from the website.[297]

One Amazon business practice that encourages counterfeiting is that, by default, seller accounts on Amazon are set to use "commingled inventory". With this practice, the goods that a seller sends to Amazon are mixed with those of the producer of the product and with those of all other sellers that supply what is supposed to be the same product.[305]

In June 2019, BuzzFeed reported that some products identified on the site as "Amazon's choice" were low quality, had a history of customer complaints, and exhibited evidence of product review manipulation.[306]

In August 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported that they had found more than 4,000 items for sale on Amazon's site that had been declared unsafe by federal agencies, had misleading labels or had been banned by federal regulators.[307]

In the wake of the WSJ investigation, three U.S. senators – Richard Blumenthal, Ed Markey, and Bob Menendez – sent an open letter to Jeff Bezos demanding him to take action about the selling of unsafe items on the site. The letter said that "Unquestionably, Amazon is falling short of its commitment to keeping safe those consumers who use its massive platform."[308] The letter included several questions about the company's practices and gave Bezos a deadline to respond by September 29, 2019, saying "We call on you to immediately remove from the platform all the problematic products examined in the recent WSJ report; explain how you are going about this process; conduct a sweeping internal investigation of your enforcement and consumer safety policies; and institute changes that will continue to keep unsafe products off your platform."[308] Earlier in the same month, senators Blumenthal and Menendez had sent Bezos a letter about the BuzzFeed report.[308]

In December 2019, The Wall Street Journal reported that some people were literally retrieving trash out of dumpsters and selling it as new products on Amazon. The reporters ran an experiment and determined that it was easy for a seller to set up an account and sell cleaned up junk as new products. In addition to trash, sellers were obtaining inventory from clearance bins, thrift stores, and pawn shops.[309][310]

In August 2020, an appeals court in California ruled that Amazon can be held liable for unsafe products sold on its website. A Californian had bought a replacement laptop battery that caught fire and caused her to sustain third-degree burns.[311]

Counterfeit media

American copyright lobbyists have accused Amazon of facilitating the sale of unlicensed CDs and DVDs particularly in the Chinese market.[312] The Chinese government has responded by announcing plans to increase regulation of Amazon (along with Apple Inc. and Taobao.com) in relation to Internet copyright infringement issues. Amazon has already had to shut down third party distributors due to pressure from the NCAC (National Copyright Administration of China).[313]

Amazon has been caught selling counterfeit books, this being books that closely mimic an authentic edition of a published work, but that were not given permission for publication by the copyright holder. One prominent example is The Sanford Guide to Antimicrobial Therapy, a non-fiction medial book. According to David Streitfeld of The New York Times, "Amazon takes a hands-off approach to what goes on in its bookstore, never checking the authenticity, much less the quality, of what it sells. It does not oversee the sellers who have flocked to its site in any organized way. That has resulted in a kind of lawlessness. Publishers, writers and groups such as the Authors Guild said counterfeiting of books on Amazon had surged. The company has been reactive rather than proactive in dealing with the issue, often taking action only when a buyer complains. Many times, they added, there is nowhere to appeal and their only recourse is to integrate even more closely with Amazon."[314] This was not the first instance of counterfeit books appearing on Amazon. According to The New York Post, the problem of counterfeit books has in fact surged, merging into another controversy of Amazon selling plagiarized books, with Martin Kleppmann, an example author, complaining that Amazon was selling pirated copies of his textbook that had "pages overlapping" and ink bleeding issues, leading to the book being unreadable and receiving negative reviews.[315] Vox argued in 2019 that Amazon directly benefits from the sale of counterfeit books, citing an example where a small-press publisher had to partner with Amazon in order to get legitimate books back on the market: "Bill Pollock, founder of the San Francisco-based programming and science guide publisher No Starch, told the New York Times that this solution was just putting even more onus on rights holders to protect themselves: “Why should we be responsible for policing Amazon for fakes? That’s their job.” No Starch has claimed they were spending “$3,000 a month and rising” to keep its search placement higher than the people who are copying it."[316]

Removal of LGBT works

In April 2009, it was publicized that some lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, feminist, and politically liberal books were being excluded from Amazon's sales rankings.[317] Various books and media were flagged as "Adult content", including children's books, self-help books, non-fiction, and non-explicit fiction. As a result, works by established authors E. M. Forster, Gore Vidal, Jeanette Winterson and D. H. Lawrence were unranked.[318] The change first received publicity on the blog of author Mark R. Probst, who reproduced an e-mail from Amazon describing a policy of de-ranking "adult" material.[317][318] However, Amazon later said that there was no policy of de-ranking lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender material and blamed the change first on a "glitch"[319] and then on "an embarrassing and ham-fisted cataloging error" that had affected 57,310 books[320] (a hacker also claimed to have been the cause of said metadata loss[321]).