Posthumanism: Difference between revisions

ITP Edits |

|||

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

'''Posthumanism''' or '''post-humanism''' (meaning "after [[humanism]]" or "beyond humanism") is a term with five definitions:<ref name="Ferrando 2013">{{cite journal| last=Ferrando | first=Francesca |title = Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations|year = 2013 |url = http://www.bu.edu/paideia/existenz/volumes/Vol.8-2Ferrando.pdf|format=PDF| issn = 1932-1066 | accessdate=2014-03-14}}</ref> |

'''Posthumanism''' or '''post-humanism''' (meaning "after [[humanism]]" or "beyond humanism") is a term with five definitions:<ref name="Ferrando 2013">{{cite journal| last=Ferrando | first=Francesca |title = Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations|year = 2013 |url = http://www.bu.edu/paideia/existenz/volumes/Vol.8-2Ferrando.pdf|format=PDF| issn = 1932-1066 | accessdate=2014-03-14}}</ref> |

||

#'''[[Antihumanism]]''': any theory that is critical of traditional humanism and traditional ideas about humanity and the [[human condition]].<ref>J. Childers/G. Hentzi eds., ''The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism'' (1995) p. 140-1</ref> |

#'''[[Antihumanism]]''': any theory that is critical of traditional humanism and traditional ideas about humanity and the [[human condition]].<ref>J. Childers/G. Hentzi eds., ''The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism'' (1995) p. 140-1</ref> |

||

#'''Cultural |

#'''[[Posthumanism#Culture_theory|Cultural Posthumanism]]''': a branch of [[culture theory|cultural theory]] critical of the foundational assumptions of [[Renaissance humanism]] and its legacy.<ref name="Esposito 2011">{{cite journal| last=Esposito | first=Roberto | authorlink = Roberto Esposito |title = Politics and human nature|year = 2011 |url = http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222|format=PDF| accessdate=2013-06-06 | doi=10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222}}</ref> that examines and questions the historical notions of “human” and "human nature”, often challenging typical notions of human subjectivity and embodiment <ref name=miah>Miah, A. (2008) A Critical History of Posthumanism. In Gordijn, B. & Chadwick R. (2008) Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity. Springer, pp.71-94).</ref> and strives to move beyond archaic concepts of "[[human nature]]" to develop ones which constantly adapt to contemporary [[technoscientific]] knowledge.<ref name="Badmington 2000">{{cite book| author = Badmington, Neil| title = Posthumanism (Readers in Cultural Criticism)| publisher = Palgrave Macmillan| year = 2000| isbn = 0-333-76538-9}}</ref> |

||

#'''[[Posthumanism#Philosophical_posthumanism|Philosophical Posthumanism]]''': a [[philosophy|philosophical]] direction which draws on cultural posthumanism, the philosophical strand examines the ethical implications of expanding the circle of moral concern and extending subjectivities beyond the human species <ref name=miah /> |

|||

#'''Philosophical posthumanism''': a [[philosophy|philosophical]] direction which is critical of the foundational assumptions of [[Renaissance humanism]] and its legacy.<ref name="Esposito 2011">{{cite journal| last=Esposito | first=Roberto | authorlink = Roberto Esposito |title = Politics and human nature|year = 2011 |url = http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222|format=PDF| accessdate=2013-06-06 | doi=10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222}}</ref> |

|||

#'''[[Posthuman#Posthumanism|Posthuman |

#'''[[Posthuman#Posthumanism|Posthuman Condition]]''': the [[deconstruction]] of the [[human condition]] by [[critical theory|critical theorists]].<ref name="Hayles 1999">{{cite book| author = [[N. Katherine Hayles|Hayles, N. Katherine]]| title = How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics| publisher = University Of Chicago Press| year = 1999| isbn = 0-226-32146-0}}</ref> |

||

#'''[[Transhumanism]]''': an ideology and movement which seeks to develop and make available technologies that [[anti-aging|eliminate aging]] and greatly [[human enhancement|enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities]], in order to achieve a "[[posthuman future]]".<ref name="Bostrom 2005">{{cite journal| last=Bostrom | first=Nick | authorlink = Nick Bostrom |title = A history of transhumanist thought|year = 2005 |url = http://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/history.pdf|format=PDF| accessdate=2006-02-21}}</ref> |

#'''[[Transhumanism]]''': an ideology and movement which seeks to develop and make available technologies that [[anti-aging|eliminate aging]] and greatly [[human enhancement|enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities]], in order to achieve a "[[posthuman future]]".<ref name="Bostrom 2005">{{cite journal| last=Bostrom | first=Nick | authorlink = Nick Bostrom |title = A history of transhumanist thought|year = 2005 |url = http://www.nickbostrom.com/papers/history.pdf|format=PDF| accessdate=2006-02-21}}</ref> |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Dooyeweerd, H. (1955/1984). A new critique of theoretical thought (Vols. 1-4). Jordan Station, Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press.</ref> "and the nature even of our selfhood." Both human and nonhuman alike function subject to a common [http://www.dooy.info/2sides.html 'law-side'], which is diverse, composed of a number of distinct law-spheres or ''aspects''. The temporal being of both human and non-human is multi-aspectual; for example, both plants and humans are bodies, functioning in the biotic aspect, and both computers and humans function in the formative and lingual aspect, but humans function in the aesthetic, juridical, ethical and faith aspects too. The Dooyeweerdian version is able to incorporate and integrate both the objectivist version and the practices version, because it allows nonhuman agents their own subject-functioning in various aspects and places emphasis on aspectual functioning (see [http://www.dooy.info/subject.object.html his radical notion of subject-object relations]). |

Dooyeweerd, H. (1955/1984). A new critique of theoretical thought (Vols. 1-4). Jordan Station, Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press.</ref> "and the nature even of our selfhood." Both human and nonhuman alike function subject to a common [http://www.dooy.info/2sides.html 'law-side'], which is diverse, composed of a number of distinct law-spheres or ''aspects''. The temporal being of both human and non-human is multi-aspectual; for example, both plants and humans are bodies, functioning in the biotic aspect, and both computers and humans function in the formative and lingual aspect, but humans function in the aesthetic, juridical, ethical and faith aspects too. The Dooyeweerdian version is able to incorporate and integrate both the objectivist version and the practices version, because it allows nonhuman agents their own subject-functioning in various aspects and places emphasis on aspectual functioning (see [http://www.dooy.info/subject.object.html his radical notion of subject-object relations]). |

||

==Emergence of philosophical posthumanism== |

|||

==Culture theory== |

|||

[[Ihab Hassan]], theorist in the [[literary theory|academic study of literature]], once stated: |

[[Ihab Hassan]], theorist in the [[literary theory|academic study of literature]], once stated: |

||

{{quote|Humanism may be coming to an end as humanism transforms itself into something one must helplessly call posthumanism.<ref name="Hassan 1977">{{cite book | author = [[Ihab Hassan|Hassan, Ihab]] | editor = Michel Benamou, Charles Caramello | title = Performance in Postmodern Culture | publisher = Coda Press | location = Madison, Wisconsin | year = 1977 | work = Performance in Postmodern Culture | chapter = Prometheus as Performer: Toward a Postmodern Culture? | isbn = 0-930956-00-1}}</ref>}} |

{{quote|Humanism may be coming to an end as humanism transforms itself into something one must helplessly call posthumanism.<ref name="Hassan 1977">{{cite book | author = [[Ihab Hassan|Hassan, Ihab]] | editor = Michel Benamou, Charles Caramello | title = Performance in Postmodern Culture | publisher = Coda Press | location = Madison, Wisconsin | year = 1977 | work = Performance in Postmodern Culture | chapter = Prometheus as Performer: Toward a Postmodern Culture? | isbn = 0-930956-00-1}}</ref>}} |

||

This view predates |

This view predates most currents of posthumanism which have developed over the late 20th century in somewhat diverse, but complementary, domains of thought and practice. For example, Hassan is a known scholar whose theoretical writings expressly address [[postmodernity]] in [[society]].{{Citation needed|date=January 2009}} Beyond [[Postmodernist|postmodernist]] studies, posthumanism has been developed and deployed by various cultural theorists, often in reaction to problematic inherent assumptions within [[Humanistic|humanistic]] and [[Enlightenment|enlightenment]] thought. <ref name=miah /> |

||

Theorists who both complement and contrast Hassan include [[Michel Foucault]], [[Judith Butler]], [[Cybernetics|cyberneticists]] such as [[Gregory Bateson]], [[Warren McCullouch]], [[Norbert Weiner]], [[Bruno Latour]], [[Cary Wolfe]], [[Elaine Graham]], [[N. Katherine Hayles]], [[Donna Haraway]] [[Peter Sloterdijk]], [[Stefan Lorenz Sorgner]], [[Evan Thompson]], [[Francisco Varela]], [[Humberto Maturana]] and [[Douglas Kellner]]. Among the theorists are philosophers, such as Robert Pepperell, who have written about a "[[Posthuman#Posthumanism|posthuman condition]]", which is often substituted for the term "posthumanism".<ref name="Badmington 2000"/><ref name="Hayles 1999"/> |

|||

| ⚫ | Posthumanism |

||

| ⚫ | Posthumanism differs from classical [[humanism]] by relegating [[Humanity|humanity]] back to [[biocentrism (ethics)|one of many natural species]], thereby rejecting any claims founded on [[anthropocentric]] dominance.<ref name=wolfe>Wolfe, C. (2009). [https://www.upress.umn.edu/book-division/books/what-is-posthumanism ''''What is Posthumanism?''''] University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, Minnesota.</ref> According to this claim, humans have no inherent rights to destroy [[nature]] or set themselves above it in [[ethical]] considerations ''[[a priori and a posteriori|a priori]]''. Human [[knowledge]] is also reduced to a less controlling position, previously seen as the defining aspect of the world. The limitations and fallibility of [[Intelligence#Human intelligence|human intelligence]] are confessed, even though it does not imply abandoning the [[rationalism|rational]] tradition of [[humanism]].{{Citation needed|date=January 2009}} |

||

Proponents of a posthuman discourse, suggest that innovative advancements and emerging technologies have transcended the traditional model of the human, as proposed by [[Descartes]] among others associated with philosophy of the [[Enlightenment age|Enlightenment period]]. <ref>{{cite web|last1=Badmington|first1=Neil|title=Posthumanism|url=http://www.blackwellreference.com/public/tocnode?id=g9781405183123_chunk_g978140518312363_ss1-3|publisher=Blackwell Reference Online|accessdate=22 September 2015}}</ref> In contrast to [[Humanism|humanism]], the discourse of posthumanism seeks to redefine the boundaries surrounding modern philosophical understanding of the human. Posthumanism represents an evolution of thought beyond that of the contemporary social boundaries and is predicated on the seeking of truth within a [[Postmodernism|postmodern context]] context. In so doing, it rejects previous attempts to establish '[[Anthropological universal|anthropological universals]]' that are imbued with anthropocentric assumptions. <ref name=wolfe /> |

|||

The philosopher [[Michel Foucault]] placed posthumanism within a context that differentiated [[Humanism|humanism]] from [[Enlightenment Thought|enlightenment thought]]. According to Foucault, the two existed in a state of tension: as humanism sought to establish norms while Enlightenment thought attempted to transcend all that is material, including the boundaries that are constructed by humanistic thought. <ref name=wolfe /> Drawing on the Enlightenment’s challenges to the boundaries of humanism, posthumanism rejects the various assumptions of human dogmas (anthropological, political, scientific) and take the next step by attempting to change the nature of thought about what it means to be human. This requires not only decentering the human in multiple discourses (evolutionary, ecological, technological) but also examining those discourses to uncover inherent humanistic, anthropocentric, normative notions of humanness and the concept of the human. <ref name=miah /> |

|||

==Contemporary posthuman discourse== |

|||

Posthumanistic discourse aims to up spaces to examine what it means to be human and critically question the concept of “the human” in light of current cultural and historical contexts <ref name=miah /> In her book How We Became Posthuman, [[N. Katherine Hayles]], writes about the struggle between different versions of the posthuman as it continually co-evolves alongside intelligent machines. <ref>{{cite book|last1=Cecchetto|first1=David|title=Humanesis: Sound and Technological Posthumanism|date=2013|publisher=University of Minnesota Press|location=Minneapolis, MN}}</ref> Such coevolution, according to some strands of the posthuman discourse, allows one to extend their [[Subjectivity|subjective]] understandings of real experiences beyond the boundaries of [[Embodiment|embodied]] existence. According to Hayles view of posthuman, often referred to as technological posthumanism, [[Visual perception|visual perception]] and digital representations thus paradoxically become ever more salient. Even as one seeks to extend knowledge by deconstructing perceived boundaries, it is these same boundaries that make knowledge acquisition possible. The use of technology in a contemporary society is thought to complicate this relationship. |

|||

[[N. Katherine Hayles|Hayles]] discusses the translation of human bodies into information (as suggested by [[Hans Moravec]]) in order illuminate how the boundaries of our embodied reality have been compromised in the current age and how narrow definitions of humanness no longer apply. Because of this, according to [[N. Katherine Hayles|Hayles]], posthumanism is characterized by a loss of [[Subjectivity|subjectivity]] based on bodily boundaries. <ref name=miah /> This strand of posthumanism, including the changing notion of subjectivity and the disruption of ideas concerning what it means to be human, is often associated with [[Donna Haraway]]’s concept of the [[cyborg]].<ref name=miah /> However, [[Donna Haraway|Haraway]] has distanced herself from posthumanistic discourse due to other theorists’ use of the term to promote [[Utopianism|utopian]] views of technological innovation to extend the human biological capacity, <ref name=gane /> (even though these notions would more correctly fall into the realm of [[transhumanism]] <ref name=miah /> ). |

|||

While posthumanism is a broad and complex ideology, it has relevant implications today and for the future. It attempts to redefine [[Social structures|social structures]] without inherently humanly or even biological origins, but rather in terms of [[social system|social]] and [[Psychological|psychological]] systems where [[Consciousness|consciousness]] and [[Communication|communication]] could potentially exist as unique [[Disembodied|disembodied]] entities. Questions subsequently emerge with respect to the current use and the future of technology in shaping human existence emerge, as do new concerns with regards to [[Language|language]], [[Symbolism|symbolism]], [[Subjectivity|subjectivity]], [[Phenomenology|phenomenology]], [[Ethics|ethics]] and [[Justice|justice]].<ref name=wolfe /> |

|||

==Criticism== |

==Criticism== |

||

Some critics have argued that all forms of posthumanism have more in common than their respective proponents realize.<ref name="Winner 2005">{{cite book | author = [[Langdon Winner|Winner, Langdon]] | editor = Harold Bailie, Timothy Casey| title = Is Human Nature Obsolete?| publisher =M.I.T. Press | location = Massachusetts Institute of Technology, October 2004| isbn = 0262524287 | pages = 385–411 | chapter = Resistance is Futile: The Posthuman Condition and Its Advocates}}</ref> Posthumanism is sometimes used as a synonym for an [[ideology]] of [[technology]] known as "[[transhumanism]]" because it affirms the possibility and desirability of achieving a "[[posthuman future]]", albeit in purely [[evolutionary]] terms. However, posthumanists in the [[humanities]] and the [[arts]] are critical of transhumanism, in part, because they argue that it incorporates and extends many of the values of [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment humanism]] and [[classical liberalism]], namely [[scientism]], according to [[performance art|performance]] philosopher [[Shannon Bell]]:<ref name="Zaretsky 2005">{{cite journal| author = Zaretsky, Adam| title = Bioart in Question. Interview. |year = 2005 |url = http://magazine.ciac.ca/archives/no_23/en/entrevue.htm| accessdate=2007-01-28}}</ref> |

Some critics have argued that all forms of posthumanism have more in common than their respective proponents realize.<ref name="Winner 2005">{{cite book | author = [[Langdon Winner|Winner, Langdon]] | editor = Harold Bailie, Timothy Casey| title = Is Human Nature Obsolete?| publisher =M.I.T. Press | location = Massachusetts Institute of Technology, October 2004| isbn = 0262524287 | pages = 385–411 | chapter = Resistance is Futile: The Posthuman Condition and Its Advocates}}</ref> Posthumanism is sometimes used as a synonym for an [[ideology]] of [[technology]] known as "[[transhumanism]]" because it affirms the possibility and desirability of achieving a "[[posthuman future]]", albeit in purely [[evolutionary]] terms. However, posthumanists in the [[humanities]] and the [[arts]] are critical of transhumanism, in part, because they argue that it incorporates and extends many of the values of [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment humanism]] and [[classical liberalism]], namely [[scientism]], according to [[performance art|performance]] philosopher [[Shannon Bell]]:<ref name="Zaretsky 2005">{{cite journal| author = Zaretsky, Adam| title = Bioart in Question. Interview. |year = 2005 |url = http://magazine.ciac.ca/archives/no_23/en/entrevue.htm| accessdate=2007-01-28}}</ref> |

||

{{quote|[[Altruism]], [[Mutualism|mutualism]], [[Humanism|humanism]] are the soft and slimy [[Virtues|virtues]] that underpin [[Liberal capitalism|liberal capitalism]]. Humanism has always been integrated into discourses of exploitation: [[Colonialism|colonialism]], [[Imperialism|imperialism]], [[Neoimperialism|neoimperialism]], [[Democracy|democracy]], and of course, American democratization. One of the serious flaws in [[Transhumanism|transhumanism]] is the importation of liberal-human values to the biotechno enhancement of the human. Posthumanism has a much stronger critical edge attempting to develop through enactment new understandings of the [[Self and Others|self and others]], [[Essence|essence]], [[Consciousness|consciousness]], [[Intelligence|intelligence]], [[Reason|reason]], [[Agency|agency]], [[Intimacy|intimacy]], [[Life|life]], [[Embodiment|embodiment]], [[Identity|identity]] and the [[Body|body]].<ref name="Zaretsky 2005"/>}} |

{{quote|[[Altruism]], [[Mutualism|mutualism]], [[Humanism|humanism]] are the soft and slimy [[Virtues|virtues]] that underpin [[Liberal capitalism|liberal capitalism]]. Humanism has always been integrated into discourses of exploitation: [[Colonialism|colonialism]], [[Imperialism|imperialism]], [[Neoimperialism|neoimperialism]], [[Democracy|democracy]], and of course, American democratization. One of the serious flaws in [[Transhumanism|transhumanism]] is the importation of liberal-human values to the biotechno enhancement of the human. Posthumanism has a much stronger critical edge attempting to develop through enactment new understandings of the [[Self and Others|self and others]], [[Essence|essence]], [[Consciousness|consciousness]], [[Intelligence|intelligence]], [[Reason|reason]], [[Agency|agency]], [[Intimacy|intimacy]], [[Life|life]], [[Embodiment|embodiment]], [[Identity|identity]] and the [[Body|body]].<ref name="Zaretsky 2005"/>}} |

||

While many modern leaders of thought are accepting of nature of ideologies described by posthumanism, some are more skeptical of the term. [[Donna Haraway]] author of [[Cyborg Manifesto]], |

While many modern leaders of thought are accepting of nature of ideologies described by posthumanism, some are more skeptical of the term. [[Donna Haraway]], the author of [[Cyborg Manifesto|''A Cyborg Manifesto'']], has outspokenly rejected the term, though acknowledges a philosophical alignment with posthumanim. [[Donna Haraway|Haraway]] opts instead for the term of companion species, referring to nonhuman entities with which humans coexist.<ref name=gane>{{cite journal|last1=Gane|first1=Nicholas|title=When We Have Never Been Human, What Is to Be Done?: Interview with Donna Haraway|journal=Theory, Culture & Society|date=2006|volume=23|issue=7-8|page=135–158}}</ref> |

||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

Revision as of 18:20, 12 October 2015

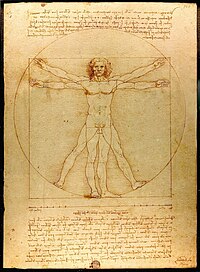

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

| Postmodernism |

|---|

| Preceded by Modernism |

| Postmodernity |

| Fields |

| Reactions |

| Related |

Posthumanism or post-humanism (meaning "after humanism" or "beyond humanism") is a term with five definitions:[1]

- Antihumanism: any theory that is critical of traditional humanism and traditional ideas about humanity and the human condition.[2]

- Cultural Posthumanism: a branch of cultural theory critical of the foundational assumptions of Renaissance humanism and its legacy.[3] that examines and questions the historical notions of “human” and "human nature”, often challenging typical notions of human subjectivity and embodiment [4] and strives to move beyond archaic concepts of "human nature" to develop ones which constantly adapt to contemporary technoscientific knowledge.[5]

- Philosophical Posthumanism: a philosophical direction which draws on cultural posthumanism, the philosophical strand examines the ethical implications of expanding the circle of moral concern and extending subjectivities beyond the human species [4]

- Posthuman Condition: the deconstruction of the human condition by critical theorists.[6]

- Transhumanism: an ideology and movement which seeks to develop and make available technologies that eliminate aging and greatly enhance human intellectual, physical, and psychological capacities, in order to achieve a "posthuman future".[7]

Philosophical posthumanism

Schatzki [2001][8] suggests there are two varieties of posthumanism of the philosophical kind:

One, which he calls 'objectivism', tries to counter the overemphasis of the subjective or intersubjective that pervades humanism, and emphasises the role of the nonhuman agents, whether they be animals and plants, or computers or other things.

A second prioritizes practices, especially social practices, over individuals (or individual subjects) which, they say, constitute the individual.

There may be a third kind of posthumanism, propounded by the philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd. Though he did not label it as 'posthumanism', he made an extensive and penetrating immanent critique of Humanism, and then constructed a philosophy that presupposed neither Humanist, nor Scholastic, nor Greek thought but started with a different ground motive [1]. Dooyeweerd prioritized law and meaningfulness as that which enables humanity and all else to exist, behave, live, occur, etc. "Meaning is the being of all that has been created," Dooyeweerd wrote [1955, I, 4],[9] "and the nature even of our selfhood." Both human and nonhuman alike function subject to a common 'law-side', which is diverse, composed of a number of distinct law-spheres or aspects. The temporal being of both human and non-human is multi-aspectual; for example, both plants and humans are bodies, functioning in the biotic aspect, and both computers and humans function in the formative and lingual aspect, but humans function in the aesthetic, juridical, ethical and faith aspects too. The Dooyeweerdian version is able to incorporate and integrate both the objectivist version and the practices version, because it allows nonhuman agents their own subject-functioning in various aspects and places emphasis on aspectual functioning (see his radical notion of subject-object relations).

Emergence of philosophical posthumanism

Ihab Hassan, theorist in the academic study of literature, once stated:

Humanism may be coming to an end as humanism transforms itself into something one must helplessly call posthumanism.[10]

This view predates most currents of posthumanism which have developed over the late 20th century in somewhat diverse, but complementary, domains of thought and practice. For example, Hassan is a known scholar whose theoretical writings expressly address postmodernity in society.[citation needed] Beyond postmodernist studies, posthumanism has been developed and deployed by various cultural theorists, often in reaction to problematic inherent assumptions within humanistic and enlightenment thought. [4]

Theorists who both complement and contrast Hassan include Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, cyberneticists such as Gregory Bateson, Warren McCullouch, Norbert Weiner, Bruno Latour, Cary Wolfe, Elaine Graham, N. Katherine Hayles, Donna Haraway Peter Sloterdijk, Stefan Lorenz Sorgner, Evan Thompson, Francisco Varela, Humberto Maturana and Douglas Kellner. Among the theorists are philosophers, such as Robert Pepperell, who have written about a "posthuman condition", which is often substituted for the term "posthumanism".[5][6]

Posthumanism differs from classical humanism by relegating humanity back to one of many natural species, thereby rejecting any claims founded on anthropocentric dominance.[11] According to this claim, humans have no inherent rights to destroy nature or set themselves above it in ethical considerations a priori. Human knowledge is also reduced to a less controlling position, previously seen as the defining aspect of the world. The limitations and fallibility of human intelligence are confessed, even though it does not imply abandoning the rational tradition of humanism.[citation needed]

Proponents of a posthuman discourse, suggest that innovative advancements and emerging technologies have transcended the traditional model of the human, as proposed by Descartes among others associated with philosophy of the Enlightenment period. [12] In contrast to humanism, the discourse of posthumanism seeks to redefine the boundaries surrounding modern philosophical understanding of the human. Posthumanism represents an evolution of thought beyond that of the contemporary social boundaries and is predicated on the seeking of truth within a postmodern context context. In so doing, it rejects previous attempts to establish 'anthropological universals' that are imbued with anthropocentric assumptions. [11]

The philosopher Michel Foucault placed posthumanism within a context that differentiated humanism from enlightenment thought. According to Foucault, the two existed in a state of tension: as humanism sought to establish norms while Enlightenment thought attempted to transcend all that is material, including the boundaries that are constructed by humanistic thought. [11] Drawing on the Enlightenment’s challenges to the boundaries of humanism, posthumanism rejects the various assumptions of human dogmas (anthropological, political, scientific) and take the next step by attempting to change the nature of thought about what it means to be human. This requires not only decentering the human in multiple discourses (evolutionary, ecological, technological) but also examining those discourses to uncover inherent humanistic, anthropocentric, normative notions of humanness and the concept of the human. [4]

Contemporary posthuman discourse

Posthumanistic discourse aims to up spaces to examine what it means to be human and critically question the concept of “the human” in light of current cultural and historical contexts [4] In her book How We Became Posthuman, N. Katherine Hayles, writes about the struggle between different versions of the posthuman as it continually co-evolves alongside intelligent machines. [13] Such coevolution, according to some strands of the posthuman discourse, allows one to extend their subjective understandings of real experiences beyond the boundaries of embodied existence. According to Hayles view of posthuman, often referred to as technological posthumanism, visual perception and digital representations thus paradoxically become ever more salient. Even as one seeks to extend knowledge by deconstructing perceived boundaries, it is these same boundaries that make knowledge acquisition possible. The use of technology in a contemporary society is thought to complicate this relationship.

Hayles discusses the translation of human bodies into information (as suggested by Hans Moravec) in order illuminate how the boundaries of our embodied reality have been compromised in the current age and how narrow definitions of humanness no longer apply. Because of this, according to Hayles, posthumanism is characterized by a loss of subjectivity based on bodily boundaries. [4] This strand of posthumanism, including the changing notion of subjectivity and the disruption of ideas concerning what it means to be human, is often associated with Donna Haraway’s concept of the cyborg.[4] However, Haraway has distanced herself from posthumanistic discourse due to other theorists’ use of the term to promote utopian views of technological innovation to extend the human biological capacity, [14] (even though these notions would more correctly fall into the realm of transhumanism [4] ).

While posthumanism is a broad and complex ideology, it has relevant implications today and for the future. It attempts to redefine social structures without inherently humanly or even biological origins, but rather in terms of social and psychological systems where consciousness and communication could potentially exist as unique disembodied entities. Questions subsequently emerge with respect to the current use and the future of technology in shaping human existence emerge, as do new concerns with regards to language, symbolism, subjectivity, phenomenology, ethics and justice.[11]

Criticism

Some critics have argued that all forms of posthumanism have more in common than their respective proponents realize.[15] Posthumanism is sometimes used as a synonym for an ideology of technology known as "transhumanism" because it affirms the possibility and desirability of achieving a "posthuman future", albeit in purely evolutionary terms. However, posthumanists in the humanities and the arts are critical of transhumanism, in part, because they argue that it incorporates and extends many of the values of Enlightenment humanism and classical liberalism, namely scientism, according to performance philosopher Shannon Bell:[16]

Altruism, mutualism, humanism are the soft and slimy virtues that underpin liberal capitalism. Humanism has always been integrated into discourses of exploitation: colonialism, imperialism, neoimperialism, democracy, and of course, American democratization. One of the serious flaws in transhumanism is the importation of liberal-human values to the biotechno enhancement of the human. Posthumanism has a much stronger critical edge attempting to develop through enactment new understandings of the self and others, essence, consciousness, intelligence, reason, agency, intimacy, life, embodiment, identity and the body.[16]

While many modern leaders of thought are accepting of nature of ideologies described by posthumanism, some are more skeptical of the term. Donna Haraway, the author of A Cyborg Manifesto, has outspokenly rejected the term, though acknowledges a philosophical alignment with posthumanim. Haraway opts instead for the term of companion species, referring to nonhuman entities with which humans coexist.[14]

See also

References

- ^ Ferrando, Francesca (2013). "Posthumanism, Transhumanism, Antihumanism, Metahumanism, and New Materialisms: Differences and Relations" (PDF). ISSN 1932-1066. Retrieved 2014-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ J. Childers/G. Hentzi eds., The Columbia Dictionary of Modern Literary and Cultural Criticism (1995) p. 140-1

- ^ Esposito, Roberto (2011). "Politics and human nature" (PDF). doi:10.1080/0969725X.2011.621222. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h Miah, A. (2008) A Critical History of Posthumanism. In Gordijn, B. & Chadwick R. (2008) Medical Enhancement and Posthumanity. Springer, pp.71-94).

- ^ a b Badmington, Neil (2000). Posthumanism (Readers in Cultural Criticism). Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-76538-9.

- ^ a b Hayles, N. Katherine (1999). How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature, and Informatics. University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32146-0.

- ^ Bostrom, Nick (2005). "A history of transhumanist thought" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-02-21.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Schatzki, T.R. 2001. Introduction: Practice theory, in The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory eds. Theodore R.Schatzki, Karin Knorr Cetina & Eike Von Savigny.

- ^ Dooyeweerd, H. (1955/1984). A new critique of theoretical thought (Vols. 1-4). Jordan Station, Ontario, Canada: Paideia Press.

- ^ Hassan, Ihab (1977). "Prometheus as Performer: Toward a Postmodern Culture?". In Michel Benamou, Charles Caramello (ed.). Performance in Postmodern Culture. Madison, Wisconsin: Coda Press. ISBN 0-930956-00-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Wolfe, C. (2009). 'What is Posthumanism?' University of Minnesota Press. Minneapolis, Minnesota.

- ^ Badmington, Neil. "Posthumanism". Blackwell Reference Online. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ Cecchetto, David (2013). Humanesis: Sound and Technological Posthumanism. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- ^ a b Gane, Nicholas (2006). "When We Have Never Been Human, What Is to Be Done?: Interview with Donna Haraway". Theory, Culture & Society. 23 (7–8): 135–158.

- ^ Winner, Langdon. "Resistance is Futile: The Posthuman Condition and Its Advocates". In Harold Bailie, Timothy Casey (ed.). Is Human Nature Obsolete?. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, October 2004: M.I.T. Press. pp. 385–411. ISBN 0262524287.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ a b Zaretsky, Adam (2005). "Bioart in Question. Interview". Retrieved 2007-01-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)