Pharaoh: Difference between revisions

←Replaced content with '{{Other uses}} the pharaoh like to touch hard penuses' Tag: blanking |

Undid revision 810671806 by 24.180.22.205 (talk) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

{{lead too short|date=January 2015}} |

|||

the pharaoh like to touch hard penuses |

|||

{{Infobox former monarchy |

|||

| royal_title = Pharaoh |

|||

| realm = [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]] |

|||

| coatofarms = Double crown.svg |

|||

| coatofarmssize = 130px |

|||

| coatofarmscaption = The [[Pschent]] combined the [[Deshret|Red Crown]] of [[Lower Egypt]] and the [[Hedjet|White Crown]] of [[Upper Egypt]]. |

|||

| image = Pharaoh.svg |

|||

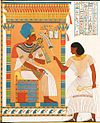

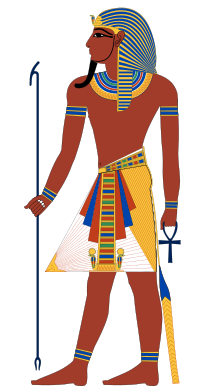

| caption = A typical depiction of a pharaoh. After [[Djoser]] of the third dynasty, pharaohs were usually depicted wearing the [[nemes]] headdress, a false beard, and an ornate [[kilt]]. |

|||

| first_monarch = [[Narmer]] or [[Menes]] (by tradition) |

|||

| last_monarch = [[Cleopatra VII|Cleopatra]] & [[Caesarion]] |

|||

| style = [[Ancient Egyptian royal titulary|Five-name titulary]] |

|||

| residence = [[List of Egyptian capitals|Varies by era]] |

|||

| appointer = [[Sacred king|Divine right]] |

|||

| began = [[Circa|c.]] 3150 BC |

|||

| ended = 30 BC |

|||

| pretender = |

|||

}} |

|||

{{Hiero|pr-ˤ3<br/>"Great house"|<hiero>O1:O29</hiero>|align=right|era=egypt}} |

|||

{{Hiero|nswt-bjt<br/>"King of Upper <br/>and Lower Egypt"|<hiero>sw:t L2:t</hiero><br/><br/><hiero>A43 A45</hiero><br/><br/><hiero>S1:t S3:t</hiero><br/><br/><hiero>S2 S4</hiero><br/><br/><hiero>S5</hiero>|align=right|era=egypt}} |

|||

'''Pharaoh''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|f|eɪ|.|r|oʊ}}, {{IPAc-en|f|ɛr|.|oʊ}}<ref>''Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition''. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 928</ref><ref name="df">''[[Dictionary.com|Dictionary Reference]]'': [http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/pharaoh pharaoh]</ref> or {{IPAc-en|f|ær|.|oʊ}}<ref name="df"/>) is the [[Vernacular|common title]] of the [[monarch]]s of [[ancient Egypt]] from the [[First Dynasty of Egypt|First Dynasty]] (c. 3150 BCE) until the [[Roman Empire|Roman Annexation of Egypt]] in 30 BCE,<ref>Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.</ref> although the actual term "Pharaoh" was not used contemporaneously for a ruler until [[Merneptah|circa 1200 BCE]]. In the early dynasty, Ancient Egyptian kings used to have up to three titles, the Horus, the Nesu Bety, and the Nebty name. The Golden Horus and Nomen and prenomen titles were later added. |

|||

During the early days prior the unity of the lower and upper kingdoms of ancient Egypt, a Deshret, the red crown, was a representation the Kingdom of lower Egypt; while the Hadjet, a white crown, was worn by the kings of the kingdom of upper Egypt. After the unification of both kingdoms into one united Egypt, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns was the official crown of kings. With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties like Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem, and Kepresh. At times, it was depicted that a combination of these headdresses or crowns would be worn together. |

|||

==Etymology== |

|||

[[Egyptian language#History|The word ''pharaoh'' ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound]] ''{{lang|egy-Latn|pr-ˤ3}}'' "great house," written with the two [[Egyptian biliteral signs|biliteral hieroglyphs]] ''{{lang|egy-Latn|[[Pr (hieroglyph)|pr]]}}'' "house" and ''{{lang|egy-Latn|ˤ3}}'' "column", here meaning "great" or "high". It was used only in larger phrases such as ''smr pr-ˤ3'' "Courtier of the High House", with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.<ref>A. Gardiner, ''Ancient Egyptian Grammar'' (3rd edn, 1957), 71–76.</ref> From the [[Twelfth dynasty of Egypt|twelfth dynasty]] onward, the word appears in a wish formula "Great House, may it [[Ankh wedja seneb|live, prosper, and be in health]]", but again only with reference to the royal palace and not the person. |

|||

During the reign of [[Thutmose III]] (''circa'' 1479–1425 BCE) in the [[New Kingdom]], after the foreign rule of the [[Hyksos]] during the [[Second Intermediate Period]], ''pharaoh'' became the form of address for a person who was king.<ref>Redmount, Carol A. "Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt." p. 89–90. Michael D. Coogan, ed. ''The Oxford History of the Biblical World'', [[Oxford University Press]]. 1998.</ref> |

|||

The earliest instance where ''pr-''ˤ''3'' is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to [[Amenhotep IV]] (Akhenaten), who reigned ''circa'' 1353–1336 BCE, which is addressed to "Pharaoh, ''all [[Ankh wedja seneb|life, prosperity, and health]]''".<ref>''Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob'', F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17. Although see also R. Mond and O. Myers (1940), ''Temples of Armant'', pl. 93, 5, for an instance possibly dating from the reign of [[Thutmose III]].</ref> During the [[Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt|eighteenth dynasty]] (16th to 14th centuries BCE) the title pharaoh was employed as a [[Deference|reverential designation]] of the ruler. About the [[Twenty-first Dynasty of Egypt|late twenty-first dynasty]] (10th century BCE), however, instead of being used alone as before, it began to be added to the other titles before the ruler's name, and from the [[Twenty-fifth Dynasty of Egypt|twenty-fifth dynasty]] (eighth to seventh centuries BCE) it was, at least in ordinary usage, the only [[epithet]] prefixed to the royal [[Appelative|appellative]].<ref>"pharaoh" in ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica]]. Ultimate Reference Suite''. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.</ref> |

|||

From the [[Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt|nineteenth dynasty]] onward ''pr-ˤ3'' on its own was used as regularly as '''''[http://medu.ipetisut.com/index.php?og=majesty ḥm]''''', "Majesty".<ref name="Denise M. Doxey">{{cite book|author=Denise M. Doxey|url=https://books.google.de/books?id=1Jead15xcBQC&pg=PA119&lpg=PA119&dq=ity+egyptian+sovereign&source=bl&ots=YAlwBPtJsS&sig=x9srPQL5dYgEqCn3pvziXVfdonI&hl=en&sa=X&redir_esc=y#v=snippet&q=majesty&f=false|title=Egyptian Non-Royal Epithets in the Middle Kingdom: A Social and Historical Analysis|publisher=BRILL|year=1998|page=151|isbn=9789004110779}}</ref>{{refn|group="note"|The Bible refers to Egypt as the "Land of [[Ham (son of Noah)|Ham]]"}} The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler, particularly by the [[Twenty-second dynasty of Egypt|twenty-second dynasty]] and [[Twenty-third dynasty of Egypt|twenty-third dynasty]].{{citation needed|date=October 2010}} |

|||

For instance, the first dated appearance of the title pharaoh being attached to a ruler's name occurs in Year 17 of [[Siamun]] on a fragment from the [[Karnak]] Priestly Annals. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of Pharaoh Siamun.<ref>J-M. Kruchten, Les annales des pretres de Karnak (OLA 32), 1989, pp.474–8.</ref> This new practice was continued under his successor Psusennes II and the twenty-second dynasty kings. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king "Pharaoh Shoshenk, beloved of Amun", whom all Egyptologists concur was [[Shoshenq I]]—the founder of the [[Twenty-second Dynasty of Egypt|Twenty-second dynasty]]—including [[Alan Gardiner]] in his original 1933 publication of this stela.<ref>Alan Gardiner, "The Dakhleh Stela", ''[[Journal of Egyptian Archaeology]]'', Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (May, 1933) pp. 193–200.</ref> Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the old custom of referring to the sovereign simply as ''pr-ˤ3'' continued in traditional Egyptian narratives.{{citation needed|date=October 2010}} |

|||

By this time, the [[Egyptian language|Late Egyptian]] word is reconstructed to have been pronounced {{IPA|*[par-ʕoʔ]}} whence Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Φερων.<ref>Herodotus, Histories 2.111.1. See {{cite book | publisher=Brill| year=1972 |title=Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary |author=Anne Burton}}, commenting on ch. 59.1.</ref> In the [[Old Testament]] of the [[Bible]], the title also occurs as פרעה {{IPA|[par‘ōh]}};<ref name="Pharaoh פרעה">[http://arilipinski.com/pesach-haggadah-abravanel-comment-explained-by-ari-lipinski/ Elazar Ari Lipinski: ''Pesach - A holiday of questions. About the Haggadah-Commentary Zevach Pesach of Rabbi Isaak Abarbanel (1437–1508).] Explaining the meaning of the name Pharaoh.'' Published first in German in the official quarterly of the Organization of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria: ''Jüdisches Leben in Bayern. Mitteilungsblatt des Landesverbandes der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden in Bayern.'' Pessach-Ausgabe = Nr. 109, 2009, {{ZDB|2077457-6}}, S. 3–4.</ref> from that, [[Septuagint]] φαραώ ''pharaō'' and then [[Late Latin]] ''pharaō'', both ''-n'' stem nouns. The Qur'an likewise spells it فرعون ''fir'awn'' with "n" (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Exodus story, by contrast to the good king Aziz in sura 12's Joseph story). Interestingly, the Arabic combines the original pharyngeal [[ayin]] sound from Egyptian, along with the ''-n'' ending from Greek. |

|||

English at first spelt it "Pharao", but the King James Bible revived "Pharaoh" with "h" from the Hebrew. Meanwhile in Egypt itself, {{IPA|*[par-ʕoʔ]}} evolved into [[Coptic language|Sahidic Coptic]] {{coptic|ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ}} ''prro'' and then ''rro'' (by mistaking ''p-'' as the definite article prefix "the" from ancient Egyptian ''p3'').<ref>Walter C. Till: "Koptische Grammatik." ''VEB Verläg Enzyklopädie'', Leipzig, 1961. p. 62.</ref> |

|||

Other notable epithets, ''[http://medu.ipetisut.com/index.php?og=king nsw]'' is translated to "king", ''[http://medu.ipetisut.com/index.php?og=sovereign&ml=0&mucn=G7 ity]'' for "monarch or soveriegn", ''[http://medu.ipetisut.com/index.php?og=lord nb]'' for "lord".<ref name="Denise M. Doxey"/>{{refn|group="note"|nb.f means "his lord", the monarchs were introduced with (.f) for his, (.k) for your.<ref name="Denise M. Doxey"/>}} and ''[http://medu.ipetisut.com/index.php?og=ruler heqa]'' for "ruler". |

|||

==Regalia== |

|||

===Scepters and staves=== |

|||

[[File:Khasekhemwy-BeadedScepter MuseumOfFineArtsBoston.png|thumb|Beaded Scepter of Khasekhemwy (Museum of Fine Arts in Boston).]] |

|||

[[Scepter]]s and staves were a general sign of authority in [[ancient Egypt]].<ref name="TW158">Wilkinson, Toby A.H. ''Early Dynastic Egypt''. Routledge, 2001, p. 158.</ref> One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of [[Khasekhemwy]] in [[Abydos, Egypt|Abydos]].<ref name="TW158"/> Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Pharaoh [[Anedjib]] is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called ''mks''-staff.<ref name="TW159">Wilkinson, Toby A.H. ''Early Dynastic Egypt''. Routledge, 2001, p. 159.</ref> The scepter with the longest history seems to be the ''heqa''-scepter, sometimes described as the shepherd's crook.<ref name="TW160">Wilkinson, Toby A.H. ''Early Dynastic Egypt''. Routledge, 2001, p. 160.</ref> The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to pre-dynastic times. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to the late Naqada period. |

|||

Another scepter associated with the king is the [[Was (sceptre)|''was''-scepter]].<ref name="TW160"/> This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the ''was''-scepter date to the [[First dynasty of Egypt|first dynasty]]. The ''was''-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities. |

|||

The [[flail]] later was closely related to the ''heqa''-scepter (the [[crook and flail]]), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle which is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the [[Narmer Macehead]].<ref name="TW161">Wilkinson, Toby A.H. ''Early Dynastic Egypt''. Routledge, 2001, p. 161.</ref> |

|||

===The Uraeus=== |

|||

The earliest evidence known of the [[Uraeus]]—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of [[Den (Pharaoh)|Den]] from the [[First dynasty of Egypt|first dynasty]]. The cobra supposedly protected the pharaoh by spitting fire at its enemies.<ref name="TW162">Wilkinson, Toby A.H. ''Early Dynastic Egypt''. Routledge, 2001, p. 162.</ref> |

|||

==Crowns and headdresses== |

|||

{{Main|Crowns of Egypt}} |

|||

{| border="1" align="center" |

|||

|+ '''Narmer Palette''' |

|||

|- |

|||

| [[File:NarmerPalette-CloseUpOfNarmer-ROM.png|300px]] || [[File:NarmerPalette-CloseUpOfProcession-ROM.png|350px]] |

|||

|- |

|||

| Narmer wearing the white crown || Narmer wearing the red crown |

|||

|} |

|||

===Deshret=== |

|||

The red crown of Lower Egypt, the [[Deshret]] crown, dates back to pre-dynastic times. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from [[Naqada]], and later, king [[Narmer]] is shown wearing the red crown on both the [[Narmer macehead]] and the [[Narmer palette]]. |

|||

===Hedjet=== |

|||

The white crown of Upper Egypt, the [[Hedjet]] crown, is shown on the Qustul incense burner which dates to the [[Predynastic Egypt|pre-dynastic period]]. Later, [[King Scorpion]] was depicted wearing the white crown, as was Narmer. |

|||

===Pschent=== |

|||

This is the combination of the Deshret and Hedjet crowns into a double crown, called the [[Pschent]] crown. It is first documented in the middle of the [[First dynasty of Egypt|first dynasty]]. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of [[Djet]], and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.<ref name="TW">Wilkinson, Toby A.H. ''Early Dynastic Egypt''. Routledge, 2001 {{ISBN|978-0-415-26011-4}}</ref> |

|||

===Khat=== |

|||

[[File:Den1.jpg|thumb|right|Den]] |

|||

The [[Khat (apparel)|''khat'']] headdress consists of a kind of "kerchief" whose end is tied similarly to a [[ponytail]]. The earliest depictions of the ''khat'' headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of [[Djoser]]. |

|||

===Nemes=== |

|||

The [[Nemes]] headdress dates from the time of Djoser. It is the most common type of crown that has been depicted throughout Pharaonic Egypt. Any other type of crown, apart from the Khat headdress, has been commonly depicted on top of the [[Nemes]]. The statue from his [[Serdab]] in [[Saqqara]] shows the king wearing the ''nemes'' headdress.<ref name="TW"/> |

|||

[[File:Kneeling Statuette of Pepy I, ca. 2338-2298 B.C.E., 39.121.jpg|left|thumb|Statuette of Pepy I (ca. 2338-2298 B.C.E.) wearing a nemes headdress [[Brooklyn Museum]]]] |

|||

===Atef=== |

|||

Osiris is shown to wear the [[Atef]] crown, which is an elaborate [[Hedjet]] with feathers and disks. Depictions of Pharaohs wearing the [[Atef]] crown originate from the Old Kingdom. |

|||

===Hemhem=== |

|||

The [[Hemhem]] crown is usually depicted on top of [[Nemes]], [[Pschent]], or [[Deshret]] crowns. It is an ornate triple [[Atef]] with corkscrew sheep horns and usually two uraei. The usage (depiction) of this crown begins during the Early 18th dynasty of Egypt. |

|||

===Khepresh=== |

|||

Also called the blue crown, the [[Khepresh]] crown has been depicted since the New Kingdom. |

|||

===Physical evidence=== |

|||

Egyptologist [[Bob Brier]] has noted that despite its widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown ever has been discovered. [[Tutankhamun]]'s tomb, discovered largely intact, did contain such regalia as his [[crook and flail]], but no crown was found, however, among the funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.<ref>Shaw, Garry J. ''The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign''. Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 21, 77.</ref> |

|||

It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties. Brier's speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so a dead pharaoh likely could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor.<ref>Bob Brier, ''The Murder of Tutankhamen'', 1998, p. 95.</ref> |

|||

==Titles== |

|||

{{main|Ancient Egyptian royal titulary}} |

|||

During the [[Early Dynastic Period (Egypt)|early dynastic period]] kings had as many as three titles. The ''[[Horus|Horus name]]'' is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The ''Nesu Bity'' name was added during the [[First dynasty of Egypt|first dynasty]]. The ''Nebty'' name was first introduced toward the end of the [[First dynasty of Egypt|first dynasty]].<ref name="TW" /> The Golden falcon (''bik-nbw'') name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a [[Cartouche (hieroglyph)|cartouche]].<ref name="DH"/> By the [[Middle Kingdom of Egypt|Middle Kingdom]], the official [[Ancient Egyptian royal titulary|titulary]] of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, nebty, golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen<ref>Ian Shaw, ''The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt'', Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477</ref> for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known. |

|||

===''Nesu Bity'' name=== |

|||

The ''Nesu Bity'' name, also known as [[Prenomen (ancient Egypt)|Prenomen]], was one of the new developments from the reign of [[Den (pharaoh)|Den]]. The name would follow the glyphs for the "Sedge and the Bee". The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The ''nsw bity'' name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.<ref name="TW"/> |

|||

===Horus name=== |

|||

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a [[serekh]]. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king [[Ka (pharaoh)|Ka]], before the first dynasty.<ref>Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp. 57f.</ref> The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with [[Horus]]. [[Hor-Aha|Aha]] refers to "Horus the fighter", [[Djer]] refers to "Horus the strong", etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. [[Khasekhemwy]] refers to "Horus: the two powers are at peace", while [[Nebra (Pharaoh)|Nebra]] refers to "Horus, Lord of the Sun".<ref name="TW" /> |

|||

===''Nebty'' name=== |

|||

The earliest example of a ''nebty'' name comes from the reign of king [[Hor-Aha|Aha]] from the [[First dynasty of Egypt|first dynasty]]. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt [[Nekhbet]] and [[Wadjet]].<ref name="TW"/><ref name="DH"/> The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).<ref name="TW"/> |

|||

===Golden Horus=== |

|||

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or ''nbw'' sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the [[Egyptian pyramids#Pyramid symbolism|pyramid]]s and [[obelisk]]s are representations of (golden) [[sun]]-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.<ref name="TW"/> |

|||

===Nomen and prenomen=== |

|||

The [[Prenomen (ancient Egypt)|prenomen]] and [[Nomen (ancient Egypt)|nomen]] were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (''nsw bity'') or Lord of the Two Lands (''nebtawy'') title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of [[Ra|Re]]. The nomen often followed the title Son of Re (''sa-ra'') or the title Lord of Appearances (''neb-kha'').<ref name="DH">Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. ''The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt''. Thames & Hudson. 2004. {{ISBN|0-500-05128-3}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:S F-E-CAMERON EGYPT 2005 RAMASEUM 01360.JPG|thumb|450px|center|Nomen and prenomen of [[Ramesses III]] ]] |

|||

==See also== |

|||

{{portal|Ancient Egypt|Monarchy}} |

|||

* [[List of pharaohs]] |

|||

* [[Coronation of the pharaoh]] |

|||

* [[Great Royal Wife]], the chief wife of a male pharaoh |

|||

* [[Egyptian chronology]] |

|||

* [[Pharaohs in the Bible]] |

|||

* [[Pharaoh (novel)|''Pharaoh'']], a historical novel written by [[Bolesław Prus]] |

|||

==Notes== |

|||

{{reflist|group="note"}} |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

* Shaw, Garry J. ''The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign'', Thames and Hudson, 2012. |

|||

* Sir [[Alan Gardiner]] ''Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs'', Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76. |

|||

* Jan Assmann, "Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten," in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), ''Menschen - Heros - Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne'' (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), pp. 11–26. |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Sister project links|wikt=pharaoh|commons=Category:Pharaohs|v=no|n=no|q=no|s=no|b=Ancient History/Egypt/Pharaohs}} |

|||

* [http://www.digitalegypt.ucl.ac.uk/Welcome.html Digital Egypt for Universities] |

|||

* [http://www.ancient-egypt-online.com/ancient-egyptian-pharaohs.html#famous-pharaohs 10 Influential Pharaohs] |

|||

{{Wikivoyage|Pharaohs}} |

|||

{{Ancient Egypt topics}} |

|||

{{Pharaohs}} |

|||

{{Ancient Egyptian royal titulary}} |

|||

[[Category:Ancient Egyptian titles]] |

|||

[[Category:Heads of state]] |

|||

[[Category:Royal titles]] |

|||

[[Category:Noble titles]] |

|||

[[Category:Pharaohs|*]] |

|||

[[Category:Positions of authority]] |

|||

[[Category:Torah monarchs]] |

|||

[[Category:Torah people]] |

|||

[[Category:Titles of national or ethnic leadership]] |

|||

[[Category:Deified people]] |

|||

[[Category:Egyptian royal titles]] |

|||

Revision as of 18:45, 16 November 2017

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Style | Five-name titulary |

| First monarch | Narmer or Menes (by tradition) |

| Last monarch | Cleopatra & Caesarion |

| Formation | c. 3150 BC |

| Abolition | 30 BC |

| Residence | Varies by era |

| Appointer | Divine right |

| ||

| pr-ˤ3 "Great house" in hieroglyphs | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| nswt-bjt "King of Upper and Lower Egypt" in hieroglyphs | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Pharaoh (/ˈfeɪ.roʊ/, /fɛr.oʊ/[1][2] or /fær.oʊ/[2]) is the common title of the monarchs of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BCE) until the Roman Annexation of Egypt in 30 BCE,[3] although the actual term "Pharaoh" was not used contemporaneously for a ruler until circa 1200 BCE. In the early dynasty, Ancient Egyptian kings used to have up to three titles, the Horus, the Nesu Bety, and the Nebty name. The Golden Horus and Nomen and prenomen titles were later added.

During the early days prior the unity of the lower and upper kingdoms of ancient Egypt, a Deshret, the red crown, was a representation the Kingdom of lower Egypt; while the Hadjet, a white crown, was worn by the kings of the kingdom of upper Egypt. After the unification of both kingdoms into one united Egypt, the Pschent, the combination of both the red and white crowns was the official crown of kings. With time new headdresses were introduced during different dynasties like Khat, Nemes, Atef, Hemhem, and Kepresh. At times, it was depicted that a combination of these headdresses or crowns would be worn together.

Etymology

The word pharaoh ultimately derives from the Egyptian compound pr-ˤ3 "great house," written with the two biliteral hieroglyphs pr "house" and ˤ3 "column", here meaning "great" or "high". It was used only in larger phrases such as smr pr-ˤ3 "Courtier of the High House", with specific reference to the buildings of the court or palace.[4] From the twelfth dynasty onward, the word appears in a wish formula "Great House, may it live, prosper, and be in health", but again only with reference to the royal palace and not the person.

During the reign of Thutmose III (circa 1479–1425 BCE) in the New Kingdom, after the foreign rule of the Hyksos during the Second Intermediate Period, pharaoh became the form of address for a person who was king.[5]

The earliest instance where pr-ˤ3 is used specifically to address the ruler is in a letter to Amenhotep IV (Akhenaten), who reigned circa 1353–1336 BCE, which is addressed to "Pharaoh, all life, prosperity, and health".[6] During the eighteenth dynasty (16th to 14th centuries BCE) the title pharaoh was employed as a reverential designation of the ruler. About the late twenty-first dynasty (10th century BCE), however, instead of being used alone as before, it began to be added to the other titles before the ruler's name, and from the twenty-fifth dynasty (eighth to seventh centuries BCE) it was, at least in ordinary usage, the only epithet prefixed to the royal appellative.[7]

From the nineteenth dynasty onward pr-ˤ3 on its own was used as regularly as ḥm, "Majesty".[8][note 1] The term, therefore, evolved from a word specifically referring to a building to a respectful designation for the ruler, particularly by the twenty-second dynasty and twenty-third dynasty.[citation needed]

For instance, the first dated appearance of the title pharaoh being attached to a ruler's name occurs in Year 17 of Siamun on a fragment from the Karnak Priestly Annals. Here, an induction of an individual to the Amun priesthood is dated specifically to the reign of Pharaoh Siamun.[9] This new practice was continued under his successor Psusennes II and the twenty-second dynasty kings. For instance, the Large Dakhla stela is specifically dated to Year 5 of king "Pharaoh Shoshenk, beloved of Amun", whom all Egyptologists concur was Shoshenq I—the founder of the Twenty-second dynasty—including Alan Gardiner in his original 1933 publication of this stela.[10] Shoshenq I was the second successor of Siamun. Meanwhile, the old custom of referring to the sovereign simply as pr-ˤ3 continued in traditional Egyptian narratives.[citation needed]

By this time, the Late Egyptian word is reconstructed to have been pronounced *[par-ʕoʔ] whence Herodotus derived the name of one of the Egyptian kings, Φερων.[11] In the Old Testament of the Bible, the title also occurs as פרעה [par‘ōh];[12] from that, Septuagint φαραώ pharaō and then Late Latin pharaō, both -n stem nouns. The Qur'an likewise spells it فرعون fir'awn with "n" (here, always referring to the one evil king in the Exodus story, by contrast to the good king Aziz in sura 12's Joseph story). Interestingly, the Arabic combines the original pharyngeal ayin sound from Egyptian, along with the -n ending from Greek.

English at first spelt it "Pharao", but the King James Bible revived "Pharaoh" with "h" from the Hebrew. Meanwhile in Egypt itself, *[par-ʕoʔ] evolved into Sahidic Coptic ⲡⲣ̅ⲣⲟ prro and then rro (by mistaking p- as the definite article prefix "the" from ancient Egyptian p3).[13]

Other notable epithets, nsw is translated to "king", ity for "monarch or soveriegn", nb for "lord".[8][note 2] and heqa for "ruler".

Regalia

Scepters and staves

Scepters and staves were a general sign of authority in ancient Egypt.[14] One of the earliest royal scepters was discovered in the tomb of Khasekhemwy in Abydos.[14] Kings were also known to carry a staff, and Pharaoh Anedjib is shown on stone vessels carrying a so-called mks-staff.[15] The scepter with the longest history seems to be the heqa-scepter, sometimes described as the shepherd's crook.[16] The earliest examples of this piece of regalia dates to pre-dynastic times. A scepter was found in a tomb at Abydos that dates to the late Naqada period.

Another scepter associated with the king is the was-scepter.[16] This is a long staff mounted with an animal head. The earliest known depictions of the was-scepter date to the first dynasty. The was-scepter is shown in the hands of both kings and deities.

The flail later was closely related to the heqa-scepter (the crook and flail), but in early representations the king was also depicted solely with the flail, as shown in a late pre-dynastic knife handle which is now in the Metropolitan museum, and on the Narmer Macehead.[17]

The Uraeus

The earliest evidence known of the Uraeus—a rearing cobra—is from the reign of Den from the first dynasty. The cobra supposedly protected the pharaoh by spitting fire at its enemies.[18]

Crowns and headdresses

|

|

| Narmer wearing the white crown | Narmer wearing the red crown |

Deshret

The red crown of Lower Egypt, the Deshret crown, dates back to pre-dynastic times. A red crown has been found on a pottery shard from Naqada, and later, king Narmer is shown wearing the red crown on both the Narmer macehead and the Narmer palette.

Hedjet

The white crown of Upper Egypt, the Hedjet crown, is shown on the Qustul incense burner which dates to the pre-dynastic period. Later, King Scorpion was depicted wearing the white crown, as was Narmer.

Pschent

This is the combination of the Deshret and Hedjet crowns into a double crown, called the Pschent crown. It is first documented in the middle of the first dynasty. The earliest depiction may date to the reign of Djet, and is otherwise surely attested during the reign of Den.[19]

Khat

The khat headdress consists of a kind of "kerchief" whose end is tied similarly to a ponytail. The earliest depictions of the khat headdress comes from the reign of Den, but is not found again until the reign of Djoser.

Nemes

The Nemes headdress dates from the time of Djoser. It is the most common type of crown that has been depicted throughout Pharaonic Egypt. Any other type of crown, apart from the Khat headdress, has been commonly depicted on top of the Nemes. The statue from his Serdab in Saqqara shows the king wearing the nemes headdress.[19]

Atef

Osiris is shown to wear the Atef crown, which is an elaborate Hedjet with feathers and disks. Depictions of Pharaohs wearing the Atef crown originate from the Old Kingdom.

Hemhem

The Hemhem crown is usually depicted on top of Nemes, Pschent, or Deshret crowns. It is an ornate triple Atef with corkscrew sheep horns and usually two uraei. The usage (depiction) of this crown begins during the Early 18th dynasty of Egypt.

Khepresh

Also called the blue crown, the Khepresh crown has been depicted since the New Kingdom.

Physical evidence

Egyptologist Bob Brier has noted that despite its widespread depiction in royal portraits, no ancient Egyptian crown ever has been discovered. Tutankhamun's tomb, discovered largely intact, did contain such regalia as his crook and flail, but no crown was found, however, among the funerary equipment. Diadems have been discovered.[20]

It is presumed that crowns would have been believed to have magical properties. Brier's speculation is that crowns were religious or state items, so a dead pharaoh likely could not retain a crown as a personal possession. The crowns may have been passed along to the successor.[21]

Titles

During the early dynastic period kings had as many as three titles. The Horus name is the oldest and dates to the late pre-dynastic period. The Nesu Bity name was added during the first dynasty. The Nebty name was first introduced toward the end of the first dynasty.[19] The Golden falcon (bik-nbw) name is not well understood. The prenomen and nomen were introduced later and are traditionally enclosed in a cartouche.[22] By the Middle Kingdom, the official titulary of the ruler consisted of five names; Horus, nebty, golden Horus, nomen, and prenomen[23] for some rulers, only one or two of them may be known.

Nesu Bity name

The Nesu Bity name, also known as Prenomen, was one of the new developments from the reign of Den. The name would follow the glyphs for the "Sedge and the Bee". The title is usually translated as king of Upper and Lower Egypt. The nsw bity name may have been the birth name of the king. It was often the name by which kings were recorded in the later annals and king lists.[19]

Horus name

The Horus name was adopted by the king, when taking the throne. The name was written within a square frame representing the palace, named a serekh. The earliest known example of a serekh dates to the reign of king Ka, before the first dynasty.[24] The Horus name of several early kings expresses a relationship with Horus. Aha refers to "Horus the fighter", Djer refers to "Horus the strong", etc. Later kings express ideals of kingship in their Horus names. Khasekhemwy refers to "Horus: the two powers are at peace", while Nebra refers to "Horus, Lord of the Sun".[19]

Nebty name

The earliest example of a nebty name comes from the reign of king Aha from the first dynasty. The title links the king with the goddesses of Upper and Lower Egypt Nekhbet and Wadjet.[19][22] The title is preceded by the vulture (Nekhbet) and the cobra (Wadjet) standing on a basket (the neb sign).[19]

Golden Horus

The Golden Horus or Golden Falcon name was preceded by a falcon on a gold or nbw sign. The title may have represented the divine status of the king. The Horus associated with gold may be referring to the idea that the bodies of the deities were made of gold and the pyramids and obelisks are representations of (golden) sun-rays. The gold sign may also be a reference to Nubt, the city of Set. This would suggest that the iconography represents Horus conquering Set.[19]

Nomen and prenomen

The prenomen and nomen were contained in a cartouche. The prenomen often followed the King of Upper and Lower Egypt (nsw bity) or Lord of the Two Lands (nebtawy) title. The prenomen often incorporated the name of Re. The nomen often followed the title Son of Re (sa-ra) or the title Lord of Appearances (neb-kha).[22]

See also

- List of pharaohs

- Coronation of the pharaoh

- Great Royal Wife, the chief wife of a male pharaoh

- Egyptian chronology

- Pharaohs in the Bible

- Pharaoh, a historical novel written by Bolesław Prus

Notes

References

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, Eleventh Edition. Merriam-Webster, 2007. p. 928

- ^ a b Dictionary Reference: pharaoh

- ^ Clayton, Peter A. Chronicle of the Pharaohs the Reign-by-reign Record of the Rulers and Dynasties of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson, 2012. Print.

- ^ A. Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Grammar (3rd edn, 1957), 71–76.

- ^ Redmount, Carol A. "Bitter Lives: Israel in and out of Egypt." p. 89–90. Michael D. Coogan, ed. The Oxford History of the Biblical World, Oxford University Press. 1998.

- ^ Hieratic Papyrus from Kahun and Gurob, F. LL. Griffith, 38, 17. Although see also R. Mond and O. Myers (1940), Temples of Armant, pl. 93, 5, for an instance possibly dating from the reign of Thutmose III.

- ^ "pharaoh" in Encyclopædia Britannica. Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopædia Britannica, 2008.

- ^ a b c Denise M. Doxey (1998). Egyptian Non-Royal Epithets in the Middle Kingdom: A Social and Historical Analysis. BRILL. p. 151. ISBN 9789004110779.

- ^ J-M. Kruchten, Les annales des pretres de Karnak (OLA 32), 1989, pp.474–8.

- ^ Alan Gardiner, "The Dakhleh Stela", Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, Vol. 19, No. 1/2 (May, 1933) pp. 193–200.

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 2.111.1. See Anne Burton (1972). Diodorus Siculus, Book 1: A Commentary. Brill., commenting on ch. 59.1.

- ^ Elazar Ari Lipinski: Pesach - A holiday of questions. About the Haggadah-Commentary Zevach Pesach of Rabbi Isaak Abarbanel (1437–1508). Explaining the meaning of the name Pharaoh. Published first in German in the official quarterly of the Organization of the Jewish Communities of Bavaria: Jüdisches Leben in Bayern. Mitteilungsblatt des Landesverbandes der Israelitischen Kultusgemeinden in Bayern. Pessach-Ausgabe = Nr. 109, 2009, ZDB-ID 2077457-6, S. 3–4.

- ^ Walter C. Till: "Koptische Grammatik." VEB Verläg Enzyklopädie, Leipzig, 1961. p. 62.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 158.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 159.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 160.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 161.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001, p. 162.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Wilkinson, Toby A.H. Early Dynastic Egypt. Routledge, 2001 ISBN 978-0-415-26011-4

- ^ Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign. Thames and Hudson, 2012, pp. 21, 77.

- ^ Bob Brier, The Murder of Tutankhamen, 1998, p. 95.

- ^ a b c Dodson, Aidan and Hilton, Dyan. The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson. 2004. ISBN 0-500-05128-3

- ^ Ian Shaw, The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt, Oxford University Press 2000, p. 477

- ^ Toby A. H. Wilkinson, Early Dynastic Egypt, Routledge 1999, pp. 57f.

Bibliography

- Shaw, Garry J. The Pharaoh, Life at Court and on Campaign, Thames and Hudson, 2012.

- Sir Alan Gardiner Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Third Edition, Revised. London: Oxford University Press, 1964. Excursus A, pp. 71–76.

- Jan Assmann, "Der Mythos des Gottkönigs im Alten Ägypten," in Christine Schmitz und Anja Bettenworth (hg.), Menschen - Heros - Gott: Weltentwürfe und Lebensmodelle im Mythos der Vormoderne (Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2009), pp. 11–26.