Nudity: Difference between revisions

→Private versus public: Cite for medical ethics |

m →Private versus public: Typo fix: an → and |

||

| Line 234: | Line 234: | ||

* Being in ''public'' includes potentially anyone. The meaning of public space changed as cities grew. |

* Being in ''public'' includes potentially anyone. The meaning of public space changed as cities grew. |

||

In the absence of visual barriers to being seen without clothes, privacy is maintained by social distance, as when being examined for medical purposes or receiving a massage. Violation of boundaries between doctors |

In the absence of visual barriers to being seen without clothes, privacy is maintained by social distance, as when being examined for medical purposes or receiving a massage. Violation of boundaries between doctors and patients is a serious breach of medical ethics.{{sfn|Rhodes|2001}} Between social equals, privacy is maintained by [[civil inattention]], allowing others to maintain their personal space by only glancing, not looking directly, as in a crowded elevator.{{sfn|Swartz|2015}} Civil inattention also maintains the non-sexual nature of semi-public situations in which relative or complete nakedness is necessary, such as communal bathing or changing clothes. Such activities are regulated by participants [[negotiated order|negotiating behaviors]] that avoid sexualization.{{sfn|Scott|2009}} A particular example is [[open water swimming]] in the United Kingdom, which by necessity means changing outdoors in mixed gender groups with minimal or no privacy. As a participant stated, "Open water swimming and nudity go hand in hand...People don't necessarily talk about it, but just know if you join a swimming club it's likely you will see far more genitalia than you were perhaps expecting."{{sfn|Moles|2021}}{{efn|Nudity occurs while changing, not in the water; among open water swimmers a ''naked'' swimmer is someone who wears a standard swimsuit, not a [[wetsuit]].}} In the 21st century, many situations have become [[sexualization|sexualized]] by media portrayals of any nudity as a prelude to sex.{{sfn|Cover|2003}} |

||

=== Concepts of privacy === |

=== Concepts of privacy === |

||

Revision as of 01:40, 23 June 2022

Nudity is the state of being in which a human is without clothing.[1] Nudity is culturally complex due to meanings given to various states of undress in differing social situations. In any particular society, these meanings are defined in relation to being properly dressed, not in relation to the specific body parts being exposed. Although often used interchangeably, "naked" and "nude" are also used in English to distinguish between the various meanings of being unclothed.

Nakedness and clothing are connected to many cultural categories including identity, social status and moral behavior. Contemporary social norms regarding nudity vary widely, reflecting cultural ambiguity towards the body and sexuality, and differing conceptions of what constitutes public versus private spaces. While the majority of societies require clothing in most situations, others recognize non-sexual nudity as being appropriate for some recreational, social or celebratory activities, and appreciate nudity in the arts as representing positive values. Societies such as Japan and Finland maintain traditions of communal nudity based upon the use of baths and saunas that provided alternatives to sexualization. Some societies and groups continue to disapprove of nudity not only in public but also in private based upon religious beliefs. Norms are codified to varying degrees by laws defining proper dress and indecent exposure.

The loss of body hair was one of the physical characteristics that marked the biological evolution of modern humans from their hominin ancestors. Adaptations related to hairlessness contributed to the increase in brain size, bipedalism, and the variation in human skin color. While estimates vary, for at least 90,000 years anatomically modern humans wore no clothing, the invention of which was part of the transition from being not only anatomically but behaviorally modern.

Through much of history until the early modern period, people were unclothed in public by necessity or convenience either when engaged in effortful activity, including labor and athletics; or when bathing or swimming. Such functional nudity occurred in groups that were usually but not always segregated by sex. In the colonial era Christian and Muslim cultures more frequently encountered Indigenous peoples who used clothing for decorative or ceremonial purposes but were often nude, having no concept of shame regarding the body. Social norms relating to nudity are different for men than they are for women. Individuals may intentionally violate norms relating to nudity; those without power may use nudity as a form of protest, and those with power may impose nakedness on others as a form of punishment.

Terminology

In general English usage, nude and naked are often synonyms for a human being unclothed, but take on many meanings in particular contexts. Nude derives from Norman French, while naked is from the Anglo-Saxon. To be naked is more straightforward, not being properly dressed, or if stark naked, entirely without clothes. Nudity has more social connotations, and particularly in the fine arts, positive associations with the beauty of the human body.[2]

Further synonyms and euphemisms for nudity abound, including "birthday suit", "in the altogether" and "in the buff".[3] Partial nudity may be defined as not covering the genitals or other parts of the body deemed sexual, such as the buttocks or female breasts.[4]

Prehistory

Two human evolutionary processes are significant regarding nudity; first the biological evolution of early hominids from being covered in fur to being effectively hairless, followed by the cultural evolution of adornments and clothing.[5]

In the past there have been several theories regarding why humans lost their fur, but the need to dissipate body heat remains the most widely accepted evolutionary explanation.[6][7][8] Less hair, and an increase in eccrine sweating, made it easier for early humans to cool their bodies when they moved from living in shady forest to open savanna.[9][10] The ability to dissipate excess body heat helped make possible the dramatic enlargement of the brain, the most temperature-sensitive human organ.[11]

Some of the technology for what is now called clothing may have originated to make other types of adornment, including jewelry, body paint, tattoos, and other body modifications, "dressing" the naked body without concealing it.[12][13] According to Leary and Buttermore, body adornment is one of the changes that occurred in the late Paleolithic (40,000 to 60,000 years ago) in which humans became not only anatomically modern, but also behaviorally modern and capable of self-reflection and symbolic interaction.[14] More recent studies place the use of adornment at 77,000 years ago in South Africa, and 90,000—100,000 years ago in Israel and Algeria.[15] While modesty is a factor, often overlooked purposes for body coverings are camouflage used by hunters, body armor, and costumes used to impersonate "spirit-beings".[16]

The current empirical evidence for the origin of clothing is from a 2010 study published in Molecular Biology and Evolution. That study indicates that the habitual wearing of clothing began at some point in time between 170,000 and 83,000 years ago based upon a genetic analysis indicating when clothing lice diverged from their head louse ancestors.[17] A 2017 study published in Science estimated that anatomically modern humans evolved 350,000 to 260,000 years ago.[18] Thus, humans were naked in prehistory for at least 90,000 years.

History

At different points in history and different parts of the world, clothing stopped being primarily functional and became primarily symbolic. In each culture, ornamentation of the body represented the wearer's place in society; position of authority, economic class, gender role, and marital status. Dress also served an expressive function, within the current styles of fashion. What is know about the early history of clothing is mainly from depictions of the higher classes, with few surviving artifacts. The everyday behaviors of average people are rarely represented in historical records.[19]

Ancient history

The widespread habitual use of clothing is one of the changes that mark the end of the Neolithic and the beginning of civilization. Clothing and adornment became part of the symbolic communication that marked a person's membership in their society, thus nakedness meant being at the bottom of the social scale, lacking in dignity and status.[20] In Mesopotamia, most people owned a single item of clothing, usually a linen cloth that was wrapped and tied. Lacking any clothing meant being indebted, or if a slave, not being provided with clothes.[21] In the Uruk period there was recognition of the need for laborers to remove clothing while performing many tasks, although the nakedness of workers emphasized the social difference between servants and the elite, who were clothed.[22]

For the average person, clothing changed little in ancient Egypt from the Early Dynastic Period until the Middle Kingdom, a span of 1500 years. Both men and women were bare-chested and barefoot. Servants and slaves were nude or wore loincloths. Laborers might be nude while doing tasks that made clothing impractical, such as fishermen or women doing laundry in a river. Women entertainers performed naked. Children might go without clothing until puberty, at about age 12.[23] Only women of the upper classes wore kalasiris, a dress of loose draped or translucent linen which came from just above or below the breasts to the ankles.[24] It was not until the later periods, in particular the New Kingdom (1550–1069 BCE), that functionaries in the households of the wealthy also began wearing more refined dress, and upper-class women wore elaborate dresses and ornamentation which covered their breasts. These later styles are often shown in film and TV as representing ancient Egypt in all periods.[24]

However, the social humiliation of nakedness was not associated with sin or shame regarding sexuality, which was unique to Judeo-Christian societies. From the beginning of civilization, there was ambiguity regarding everyday nakedness and the nudity in depictions of deities and heroes indicating positive meanings of the unclothed body.[25]

Male nudity was celebrated in ancient Greece to a greater degree than any culture before or since.[26][27] The status of freedom, maleness, privilege, and physical virtues were asserted by discarding everyday clothing for athletic nudity.[28] Nudity became a ritual costume by association of the naked body with the beauty and power of the gods.[29] The female nude emerged as a subject for art in the 5th century BCE, illustrating stories of women bathing both indoors and outdoors. The passive images reflected the unequal status of women in society compared to the athletic and heroic images of naked men.[30] In Sparta during the Classical period, women were also trained in athletics, and while scholars do not agree whether they also competed in the nude, the same word (gymnosis, naked or lightly clothed) was used to describe the practice. It is generally agreed that Spartan women in the classical period were nude only for specific religious and ceremonial purposes.[31] In the Hellenistic period Spartan women trained with men, and participated in more athletic events.[32]

The Greek traditions were not maintained in the later Etruscan and Roman athletics because its public nudity became associated with homoeroticism. Roman masculinity involved prudishness and paranoia about effeminacy.[33] The toga was essential to announce the status and rank of male citizens of the Roman Republic (509–27 BCE).[34] The poet Ennius declared, "exposing naked bodies among citizens is the beginning of public disgrace". Cicero endorsed Ennius' words.[35]

In the Roman Empire (27 BCE – 476 CE), the status of the upper classes was such that public nudity was of no concern for men, and also for women if only seen by their social inferiors.[36] An exception was the Roman baths (thermae), which had many social functions.[37] Mixed nude bathing may have been standard in most public baths up to the fourth century CE.[38] The Fall of the Western Roman Empire marked many social changes, including the rise of Christianity. Early Christians generally inherited the norms of dress from Jewish traditions. The exception was the Baptism, which was originally by full immersion and without clothes. Jesus was also originally depicted nude as would have been the case in Roman crucifixions.[39] The Adamites, an obscure Christian sect in North Africa originating in the second century worshiped in the nude, professing to have regained the innocence of Adam.[40]

Clothing used in the Middle East, which loosely envelopes the entire body, changed little for centuries. In part, this consistency arises from the fact that such clothing is well-suited for the climate (protecting the body from dust storms while also allowing cooling by evaporation).[41] In the societies based upon the Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), modesty generally prevailed in public, with clothing covering all parts of the body of a sexual nature. The Torah set forth laws regarding clothing and modesty (tzniut) which also separated Jews from other people in the societies they lived within.[42]

The late fourth century CE was a period of both Christian conversion and standardization of church teachings, in particular on matters of sex. The dress or nakedness of women that were not deemed respectable was also of lesser importance[43] due to the distinction between adultery, which injured third parties: her husband, father, and male relatives; while fornication with an unattached woman, likely a prostitute, courtesan or slave, was a lesser sin since it had no male victims, which in a patriarchal society might mean no victim at all.[44]

Asia

In much of Asia, traditional dress covers the entire body, similar to Western dress.[45] In stories written in China as early as the fourth century BCE, nudity is presented as an affront to human dignity, reflecting the belief that "humanness" in Chinese society is not innate, but is earned by correct behavior. However, nakedness could also be used by an individual to express contempt for others in their presence. In other stories, the nudity of women, emanating the power of yin, could nullify the yang of aggressive forces.[46]

Nudity in mixed-gender public baths was common in Japan before the effects of Western influence, which began in the 19th century and became extensive during the American occupation after World War II. The practice continues at a dwindling number of hot springs (konyoku) outside of urban areas.[47] Another Japanese tradition was the women free-divers (ama) who for 2,000 years until the 1960s collected seaweed and shellfish wearing only loincloths. Their nakedness was not shocking, since women farmers often worked bare-breasted during the summer.[48]

Mesoamerica

The Aztec city Tenochtitlán reached a population of eighty thousand before the arrival of the Spanish in 1520. Built on an island in Lake Texcoco, it was dependent upon hydraulic engineering for agriculture which also supplied bathing facilities with both steam baths (temazcales) and tubs. In the Yucatan, Mayan men and women bathed in rivers with little concern for modesty. Yet in spite of the number of hot springs in the region, there is no mention of their use for bathing by indigenous peoples. The conquistadors viewed indigenous bathing practices, which included both men and women entering temazcales naked, in terms of paganism and sexual immorality and sought to eradicate them.[49]

Post-classical history

The period between the ancient and modern world—approximately 500 to 1450 CE—saw an increasingly stratified society in Europe. At the beginning of the period, everyone other than the upper classes lived in close quarters and did not have the modern sensitivity to nudity, but slept and bathed together as necessary.[38] Later in the period, with the emergence of a middle class, clothing in the form of fashion was a significant indicator of class, and thus its lack became a greater source of embarrassment.[50]

Until the beginning of the eighth century, Christians were baptized naked to represent that they emerged from baptism without sin. The disappearance of nude baptism in the Carolingian era marked the beginning of the sexualization of the body by Christians that had previously been associated with paganism.[39] Sects with beliefs similar to the Adamites, who worshiped naked, reemerged in the early 15th century.[51]

In the 13th century theorists dealt with the issue of sexuality, Albertus Magnus favoring a more philosophical view influenced by Aristotle that sex within marriage was a natural act. However, his pupal Thomas Aquinas and others took the view of Saint Augustine that sexual desire was shameful not only as original sin, but that lust was a disorder because it undermined reason. Sexual arousal was deemed so dangerous as to be avoided except for procreation, nudity being particularly taboo, which remained until the Renaissance.[52]

Although there is a common misconception that Europeans did not bathe in the Middle Ages, public bath houses—usually segregated by sex—were popular until the 16th century, when concern for the spread of disease closed many of them.[53] The Roman baths in Bath, Somerset, were rebuilt, and used by both sexes without garments until the 15th century.[54]

In Christian Europe, the parts of the body that were required to be covered in public did not always include the female breasts. In depictions of the Madonna from the 14th century, Mary is shown with one bared breast, symbolic of nourishment and loving care.[55] During a transitional period, there continued to be positive religious images of saints, but also depictions of Eve indicating shame.[56] By 1750, artistic representations of the breast were either erotic or medical. This eroticization of the breast coincided with the persecution of women as witches.[57]

The practice known as veiling of women in public predates Islam in Persia, Syria, and Anatolia. Islamic clothing for men covers the area from the waist to the knees. The Qurʾān provides guidance on the dress of women, but not strict rulings;[41] such rulings may be found in the Hadith. In the medieval period, Islamic norms became more patriarchal, and very concerned with the chastity of women before marriage and fidelity afterward. Women were not only veiled, but segregated from society, with no contact with men not of close kinship, the presence of whom defined the difference between public and private spaces.[58]

Of particular concern for both Islam and early Christians, as they extended their control over countries that had previously been part of the Byzantine or Roman empires, was the local custom of public bathing. While Christians were mainly concerned about mixed-gender bathing, which had been common, Islam also prohibited nudity for women in the company of non-Muslim women.[59] In general, the Roman bathing facilities were adapted for separation of the genders, and the bathers retaining at least a loin-cloth as in the Turkish bath of today.

Modern history

Early modern

The Christian association of nakedness with shame and anxiety became ambivalent during the Renaissance as a result of the rediscovered art and writings of ancient Greece offering an alternative tradition of nudity as symbolic of innocence and purity which could be understood in terms of the state of man "before the fall".[60] The meaning of nudity in Europe was also changed in the 1500s by reports of naked inhabitants in the Americas, and the African slaves brought to Italy by the Portuguese. Both slavery and colonialism was the beginning of the modern association of public nakedness with savagery.[61]

Some human activities continued to require states of undress in the presence of others. Opinions regarding the health benefits of bathing varied after the 16th century when many European public bath houses closed due to concerns about the spread of disease,[53] but was generally favorable by the 19th century. This led to the establishment of gender segregated public bath houses for those who had no bathing facilities in their homes. In a number of European cities where this included the middle class, some bath houses became social establishments for men.[62] In the United States, where the middle class more often had private baths in their homes, public bath houses were built for the poor, in particular for urban immigrant populations. With the adoption of showers rather than tubs, bathing facilities were added to schools and factories.[62]

The Tokugawa period in Japan (1603–1868) was defined by the social dominance of hereditary classes, with clothing a regulated marker of status and little nudity among the upper classes. However, working populations in both rural and urban areas often dressed only in loincloths, including women in hot weather and while nursing. Lacking baths in their homes, they also frequented public bathhouses where everyone was unclothed together.[63]

Late modern and contemporary

With the opening of Japan to European visitors in the Meiji era (1868–1912), the previously normal states of undress, and the custom of mixed public bathing, became an issue for leaders concerned with Japan's international reputation. A law was established with fines for those that violated the ban on undress. Although often ignored or circumvented, the law had the effect of sexualizing the naked body in situations that had not previously been erotic.[64]

Nudism, in German Freikörperkultur (FKK), "free body culture" originated in Europe in the late 19th century as part of working class opposition to industrialization. Nudism spawned a proselytizing literature in the 1920s and 1930s and was brought to America by German immigrants in the 1930s.[65] While Christian moralists tended to condemn nudism, other Christians argued for the moral purity of the nude body compared to the corruption of the scanty clothing of the era.[66] Its proponents believed that nudism could combat social inequality, including sexual inequality.[67]

In the early 20th century, the attitudes of the general public toward the human body reflected rising consumerism, concerns regarding health and fitness, and changes in clothing fashions that sexualized the body. However, members of English families report that in the 1920s to 1940s they never saw other family members undressed, including those of the same gender. Modesty continued to prevail between married couples, even during sex.[68] In the United States, a third of women born before 1900 remained clothed during sex, while it was only eight percent for those born in the 1920s.[69] Bodily modesty is not part of the Finnish identity due to the universal use of the sauna, a historical tradition that has been maintained, which teaches from an early age that nakedness need not have anything to do with sex.[70][71]

In Germany beginning in 1893 naturist attitudes toward the body became more widely accepted in sports and in the arts.[72] There were advocates of the health benefits of sun and fresh air that instituted programs of exercise in the nude for children in groups of mixed gender, Adolf Koch founding thirteen FKK schools.[73] With the rise of Nazism in the 1930s, the nudism movement split ideologically, the socialists adopting the views of Koch, seeing his programs as part of improving the lives of the working class. Although many Nazis opposed nudity, others used it to extol the Aryan race as the standard of beauty, as reflected in the Nazi propaganda film Olympia directed by Leni Riefenstahl.[74]

Both hippies or other participants in the counterculture of the 1960s embraced nudity as part of their daily routine and to emphasize their rejection of anything artificial.[75] In the mainstream, Diana Vreeland could note in Vogue in 1970 that a bikini bottom worn alone had become fashionable for young women on beaches from Saint-Tropez to Sardinia.[76] In 1974, an article in The New York Times noted an increase in American tolerance for nudity, both at home and in public, approaching that of Europe.[77] By 1998, American attitudes toward sexuality had continued to become more liberal than in prior decades, but the reaction to total nudity in public was generally negative.[78] However, some elements of the counterculture, including nudity, continued with events such as Burning Man.[79]

Colonialism and racism

The Age of Western Colonialism was marked by more frequent encounters between Christian and Muslim cultures and Indigenous peoples of the tropics, leading to the stereotypes of the "naked savage".[80] In his diaries, Christopher Columbus writes that the natives of Guanahani were entirely naked, both men and women; and gentle. This also meant that they were seen as less than fully human, and exploitable.[81] Initially Islam exerted little influence beyond large towns, outside of which pagan norms continued. In travels in Mali in the 1350s, Muslim scholar Ibn Battuta was shocked by the casual relationships between men and women even at the court of Sultans, and the public nudity of female slaves and servants.[82]

Non-western cultures during the period were naked only by comparison to Western norms. The genitals or entire lower body of adults were covered by garments in most situations, while the upper body of both men and women might be unclothed. However, lacking the western concept of shame regarding the body, such garments might be removed in public for practical or ceremonial purposes. Children until puberty and sometimes women until marriage might be naked as having "nothing to hide".[83]

Indigenous peoples of the Americas similarly had no associations of sexuality or nudity with shame or sin. In addition European colonizers became aware of other practices, including premarital and extramarital sex, homosexuality, and cross-dressing that motivated their efforts to convert Natives to Christianity. However, characterization of others as savage may have been to justify conquest and displacement.[84]

From the 17th century, European explorers viewed the lack of clothing they encountered in Africa and Oceania as representative of a primitive state of nature, justifying their own superiority, even as they continued to admire the nudity of Greek statues. A distinction was made by colonizers between idealized nudity in art and the nakedness of Indigenous people, which was uncivilized and indicative of racial inferiority.[85][86]

Depictions of naked savages entered European popular culture in the 18th century in popular stories of tropical islands. In particular, Europeans became fascinated by the image of the Pacific island woman with bare breasts.[87] While much was made of Polynesian nakedness, European cloth was welcomed as part of traditions of wrapping the body.[88][89]

Dressing Africans in European clothes to cover their nakedness was part of converting them to Christianity.[90] In the 19th century, photographs of naked Indigenous peoples began circulating in Europe without a clear distinction between those created as commercial curiosities (or erotica) and those claiming to be scientific, or ethnographic images. Given the state of photography, it is unclear which images were posed, rather than being representative of everyday attire.[91][92] George Basden, a missionary and ethnographer who lived with the Igbo people of Nigeria published two volumes of photographs in the 1920s and 1930s. The book described images of unclothed but elaborately decorated Igbo women as indicating their high status as eligible brides who would not have thought of themselves as naked.[93]

In the early 20th century, tropical countries became tourist destinations. A German tourist guide for Bali beginning in the 1920s added to the promotion of the island as an "Eden" for Western visitors by describing the beauty of Balinese women, who were bare-breasted in everyday life and unclothed while bathing in the ocean. Soon however, the Dutch colonial administration began issuing conflicting orders regarding proper dress, which had limited effect due to some Balinese supporting tradition, others modernization.[94]

-

Four Masai tribesmen, (c. 1900)

-

Indigenous woman in German East Africa, early 20th century

-

Three Igbo women in the early 20th century

-

Fijian girl (1908). The locks of hair falling on her right shoulder show that she is unmarried. When she weds they will be cut.

-

Group portrait of a Balinese family (1929)

Indigenous traditions

Hunter-gatherer societies from prehistory to the present have something in common in addition to their lifestyle, they are naked.[95] The Europeans who first contacted tropical peoples reported that they were unashamedly naked, only occasionally wrapping themselves in capes in colder weather. This practice continued when western clothing was first introduced; for example Aboriginal Australians in 1819 wore only the jackets they were given, but not pants.[96] The encounter between the Indigenous cultures of Africa, the Americas and Oceania with Europeans had a significant effect on both cultures.[97] Western ambivalence could be expressed by responding to the nakedness of natives as either a sign of rampant sexuality or of the innocence that preceded the Fall.[98]

-

Acharya Vidyasagar, a contemporary Digambara Jain monk

-

Mru women working in Bangladesh

In India, priests of the Digambara ("skyclad") sect of Jainism and some Hindu Sadhus refrain from wearing clothing to symbolize their rejection of the material world.[99][100] In Bangladesh, the Mru people have resisted centuries of Muslim and Christian pressure to clothe their nakedness as part of religious conversion. Most retain their own religion, which includes elements of Buddhism and Animism, as well as traditional clothing: a loincloth for men and a skirt for women.[101]

In sub-Saharan Africa, full or partial nudity is observed among some Burkinabese and Nilo-Saharan (e.g. Nuba and Surma people)—during particular occasions; for example, stick-fighting tournaments in Ethiopia.[102] The revival of post-colonial culture is asserted in the adoption of traditional dress—young women wearing only beaded skirts and jewelry—in the Umkhosi Womhlanga (Reed Dance) by the Zulu and Swazi.[103] However, the authenticity and propriety of the paid performance of "bare chested" Zulu girls for international tourists is sometimes questioned.[104] Other examples of ethnic tourism reflect the visitor's desire to experience what they imagine to be an exotic culture, which includes nudity.[105]

With the independence of Ghana from English rule in 1957, the first Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah and his political party began a program that sought to eliminate undesirable practices including female genital mutilation, human trafficking, prostitution, and nudity.[106] Nudity was practiced by the Frafra, Dagarti, Kokomba, Builsa, Kassena and Lobi peoples in the Northern and Upper Regions of the country. Although the stated opposition to nudity was its association with harmful practices, its prevalence as a tradition was seen as detrimental to Ghana's reputation in the world and economic development, nakedness being associated with primitive backwardness. However anti-nudity efforts also promoted the equal status of women.[107] Some traditional practices remain, the Sefwi people of Ghana performing a ritual, "Be Me Truo" that includes dancing, singing and drama by nude women to avert disaster and promote fertility.[108]

In Brazil, the Yawalapiti—an Indigenous Xingu tribe in the Amazon Basin—practice a funeral ritual known as Quarup to celebrate life, death and rebirth. The ritual involves the presentation of all young girls who have begun menstruating since the last Quarup and whose time has come to choose a partner.[109] The Awá hunters, the male members of an Indigenous people of Brazil living in the eastern Amazon rainforest, are completely naked apart from a piece of string decorated with bird feathers tied to the end of their penises. This minimalist dress code reflects the spirit of the hunt and being overdressed may be considered ridiculous or inappropriate.[110]

On the islands of Yap State, dances by women in traditional dress that does not cover the breasts are included in the Catholic celebration of Christmas and Easter.[111]

Gender differences

Female nudity

In Western cultures, shame can result from not living up to the ideals of society with regard to physical appearance. Historically, such shame has affected women more than men. With regard to their naked bodies, the result is a tendency toward self-criticism by women, while men are less concerned by the evaluation of others.[112] In patriarchal societies, which include much of the world, norms regarding proper attire and behavior are more strict for women than for men, and the judgements for violation of these norms are more severe.[113]

In much of the world, the modesty of women is a matter not only of social custom but of the legal definition of indecent exposure. In the United States, the exposure of female nipples is a criminal offense in many states and is not usually allowed in public.[114] The inclusion of female breasts within the definition of public indecency depends upon definitions of what is allowed in public spaces and what constitutes sexual indecency. Individual women who have contested indecency laws by baring their breasts in public assert that their behavior is not sexual. In Canada, the law was changed to include a definition of a sexual context in order for behavior to be indecent.[115]

The "topfreedom" movement in the United States promotes equal rights for women to be naked above the waist in public on the same basis that would apply to men in the same circumstances.[116] The illegality of topfreedom is viewed as institutionalization of negative cultural values that affect women's body image. The law in New York State was challenged in 1986 by nine women who exposed their breasts in a public park, which led to nine years of litigation culminating with an opinion by the Court of Appeals that overturned the convictions on the basis of the women's actions not being lewd, rather than overturning the law as unconstitutional on the basis of equal protection, which is what the women sought. While the decision gave women more freedom to be top-free (e.g. while sunbathing), it did not give them equality with men. Other court decisions have given individuals the right to be briefly nude in public as a form of expression protected by the First Amendment, but not on a continuing basis for their own comfort or enjoyment as men are allowed to do.[117]

Contemporary fashion in western cultures includes partial nudity for women as an expression of empowerment in contrast to the history of the women's subordination.[118]

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding in public is forbidden in some jurisdictions, not regulated in others, and protected as a legal right in public and the workplace in still others. Where public breastfeeding is unregulated or legal, mothers may be reluctant to do so because other people may object.[119][120][121] The issue of breastfeeding is part of the sexualization of the breast in many cultures, and the perception of threat in what others perceive as non-sexual.[115] Pope Francis came out in support of public breastfeeding at church services soon after assuming the Papacy.[122]

Male nudity

Men and boys had always bathed nude in secluded rivers and lakes. Male nudity continued in England when sea bathing became popular in the 18th century, beaches were male only, but with the easier access of the 19th century, the mixing of genders became a problem. The addition of "bathing machines" at seaside resorts was not successful in maintaining standards of decency, men being nude while women wore bathing costumes.[123] However, public concern was only regarding men, it being generally accepted that boys at English beaches would be nude. This prompted complaints by visiting Americans, but Englishmen had no objection to their daughters being fully dressed on the beach with naked boys to the age of ten.[124]

In the United States and other Western countries for much of the 20th century, male nudity was the norm in gender segregated activities including summer camps,[125] swimming pools[126][127] and communal showers[128] based on cultural beliefs that females need more privacy than males.[129] Beginning in 1900, businessmen swam nude at private athletic clubs in New York City, which ended with a 1980 law requiring the admission of women.[130] For boys, this expectation might include public behavior as in 1909 when The New York Times reported that at an elementary school swim public competition the youngest boys competed in the nude.[131]

Hygiene was given as the reason for official guidelines requiring male nudity in indoor pools, allowing suits only for public competitions. Swimmers were also required to take nude showers with soap prior to entering the pool, in order to eliminate contaminants and inspect swimmers to prohibit use by those with signs of disease. During women's weekly swim hours, simple one-piece suits were allowed and sometimes supplied by the facility to insure hygiene; towels were also supplied.[132][133]

Compared to the general acceptance of boys being nude, an instance in 1947 where girls were given the same option lasted only six weeks in Highland Park, Michigan before a protest by mothers. However, only the middle school required suits, the elementary schools in the same district continued to allow girls to swim nude.[134] The policy of male nudity continued officially until 1962 but was observed into the 1970s by the YMCA and schools with gender segregated classes.[135][136][137][138]

The era of nude swimming by boys in indoor pools declined as mixed-gender usage was allowed,[127] and ended when gender equality in facilities was mandated by Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972. In the 21st century, the practice of male nude swimming is largely forgotten, or even denied to have ever existed.[136]

Private versus public

In thinking about nudity, an important dimension of culture is private-public[139] and the behavior that is normal in each domain:

- In some cultures private means being entirely alone, defining personal space. In other cultures, privacy includes family and selelcted others; intimate space.

- Semi-private includes people less well known, but familiar, defining social space.

- Semi-public includes unknown others, but in a familiar setting with expectations of shared norms being followed.

- Being in public includes potentially anyone. The meaning of public space changed as cities grew.

In the absence of visual barriers to being seen without clothes, privacy is maintained by social distance, as when being examined for medical purposes or receiving a massage. Violation of boundaries between doctors and patients is a serious breach of medical ethics.[140] Between social equals, privacy is maintained by civil inattention, allowing others to maintain their personal space by only glancing, not looking directly, as in a crowded elevator.[141] Civil inattention also maintains the non-sexual nature of semi-public situations in which relative or complete nakedness is necessary, such as communal bathing or changing clothes. Such activities are regulated by participants negotiating behaviors that avoid sexualization.[142] A particular example is open water swimming in the United Kingdom, which by necessity means changing outdoors in mixed gender groups with minimal or no privacy. As a participant stated, "Open water swimming and nudity go hand in hand...People don't necessarily talk about it, but just know if you join a swimming club it's likely you will see far more genitalia than you were perhaps expecting."[143][a] In the 21st century, many situations have become sexualized by media portrayals of any nudity as a prelude to sex.[144]

Concepts of privacy

Societies in continental Europe conceive of privacy as protecting a right to respect and personal dignity. Europeans maintain their dignity, even naked where others may see them, including sunbathing in urban parks. In America, the right to privacy is oriented toward values of liberty, especially in one's home. Americans see nakedness where others may see as surrendering "any reasonable expectation of privacy". Such cultural differences may make some laws and behaviors of other societies seem incomprehensible, since each culture assumes that their own concepts of privacy are intuitive, and thus human universals.[145]

High and low context cultures

High and low context cultures were defined by anthropologist Edward T. Hall. The behaviors and norms of a high context culture depend upon shared implicit norms that operate within a social situation, while in a low context culture behavior is more dependent upon explicit communications.[146] An example of this distinction was found in research on the behavior of French and German naturists on a nude beach. Germans are extremely low in cultural context. They are characterized by individualism, alienation, estrangement from other people, little body contact, low sensitivity to nonverbal cues, and segmentation of time and space. By contrast, the French, in their personal lives, are relatively high context: they interact within closely knit groups, they are sensitive to nonverbal cues, and they engage in relatively high amounts of body contact. To maintain public propriety on a nude beach, German naturists avoided touching themselves and others and avoid any adornments or behaviors that would call attention to the body. French naturists, on the other hand, were more likely than Germans to wear make-up and jewelry and to touch others as they would while dressed.[147]

Private nudity

Individuals vary regarding being comfortable nude in situations that are private. According to a 2004 U.S. survey by ABC News, 31% of men and 14% of women report sleeping in the nude.[148] In a 2014 survey in the U.K., 42% responded that they felt comfortable naked and 50% responded they did not. Only 22% said they often walk around the house naked, 29% slept in the nude, and 27% had gone swimming nude.[149] In a 2018 U.S. survey by USA Today, 58% reported that they slept in the nude; by generation 65% of Millennials, but only 39% of Baby boomers.[150]

Body image and shame

Body image is the perceptions and feelings of a person regarding their own body's appearance, which effects self-esteem and life satisfaction. There is evidence that the majority of women and girls in western societies have a negative body image, mainly regarding their size and weight. The sociocultural model of body image emphasizes the role of cultural ideals in the formation of an individual's body image. American ideals for women are unrealistic based upon a comparison of a healthy body mass index (BMI) with the desired BMI, which is 15% lower. Cultural ideals are transmitted by parents, peers, and the media. Men and boys are increasingly concerned with their appearance, wanting to be more muscular.[151]

In non-western cultures, body image has a different meaning, particularly in sociocentric societies in which people think of themselves as part of a group, not as individuals. In addition, where food insecurity and disease is a danger, a person growing thinner is viewed as unhealthy, a more robust body is the ideal. The evolutionary perspective is that for women, hip-to-waist ratio with emphasis on the hips and a more curvaceous body is the ideal around the world, while for men it is waist-to-chest ratio. However, westernization of cultures has resulted in an increase in body dissatisfaction worldwide.[152]

Shame is one of the moral emotions often associated with nudity.[153] Shame may be thought of as positive in response to a failure to act in accordance with moral values, thus motivating improvement in the future. However, shame is often negative as the response to perceived failures to live up to unrealistic expectations. The shame regarding nudity is one of the classic examples of the emotion, yet rather than being a positive motivator, it is considered unhealthy.[154] The universality of bodily shame is not supported by anthropological studies, which do not find the use of clothing to cover the genital areas in all societies, but instead the use of adornments to call attention to the sexuality of the body.[155]

Others argue that the shame felt when naked in public is due to valuing modesty and privacy as socially positive.[156] However, the response to public exposure of normally private behavior is embarrassment, rather than shame.[157] The absence of shame, or any other negative emotions regarding being naked, depends upon becoming unselfconscious while nude, which is the state both of children and those that practice naturism. This state is more difficult for women given the social presumption that women's bodies are always being observed and judged not only by men but other women. In a naturist environment, because everyone is naked, it becomes possible to dilute the power of social judgements and experience freedom.[112][158]

Naturists have long promoted the benefits of social nudity, but little research had been done, reflecting the generally negative assumptions surrounding public nudity. Recent studies indicate not only that social nudity promotes a positive body image, but that nudity-based interventions are helpful for those with a negative body image.[159][160] A negative body image affects overall self-esteem, which in turn reduces life satisfaction. Psychologist Keon West of Goldsmiths, University of London found that nude social interaction reduced body anxiety and promoted well-being.[161][162]

Child development

A report issued in 2009 on child sexual development in the United States by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network asserted that children have a natural curiosity about their own bodies and the bodies of others. The report recommended that parents learn what is normal in regard to nudity and sexuality at each stage of a child's development and refrain from overreacting to their children's nudity-related behaviors unless there are signs of a problem (e.g. anxiety, aggression, or sexual interactions between children not of the same age or stage of development).[163] The general advice for caregivers is to find ways of setting boundaries without giving the child a sense of shame.[164]

In childcare settings outside the home there is difficulty in determining what behavior is normal and what may be indicative of child sexual abuse (CSA). In 2018 an extensive study of Danish childcare institutions (which had, in the prior century, been tolerant of child nudity and playing doctor) found that contemporary policy had become restrictive as the result of childcare workers being charged with CSA. However, while CSA does occur, the response may be due to "moral panic" that is out of proportion with its actual frequency and over-reaction may have unintended consequences. Strict policies are being implemented not to protect children from a rare threat, but to protect workers from the accusation of CSA. The policies have created a split between childcare workers who continue to believe that behaviors involving nudity are a normal part of child development and those that advocate that children be closely supervised to prohibit such behavior.[165]

The naturist/nudist point of view is that children are "nudists at heart" and that naturism provides the ideal environment for healthy development. It is noted that modern psychology generally agrees that children can benefit from an open environment where the bodies of others their own age of both sexes are not a mystery. However, there is less agreement regarding children and adults being nude. While some doctors have taken the view that some exposure of children to adult nudity (particularly parental nudity) may be healthy, others—notably Benjamin Spock—disagreed. Spock's view was later attributed to the lingering effect of Freudianism on the medical profession.[166]

In their 1986 study on the effects of social nudity on children, Smith and Sparks concluded that "the viewing of the unclothed body, far from being destructive to the psyche, seems to be either benign or to actually provide positive benefits to the individuals involved".[167] As recently as 1996 the YMCA maintained a policy of allowing young children to accompany their parents into the locker room of the opposite gender, which some health care professionals questioned.[168] A contemporary solution has been to provide separate family changing rooms.[169]

Sex education

In general, the United States remains uniquely puritanical in its moral judgements compared to other Western, developed nations.[170] As of 2015, 37 U.S. states required that sex education curricula include lessons on abstinence and 25 required that a "just say no" approach be stressed. Studies show that early and complete sex education does not increase the likelihood of becoming sexually active, but leads to better health outcomes overall.[171] In a 2018 survey of predominantly white middle-class college students in the United States, only 9.98% of women and 7.04% of men reported seeing real people (either adults or other children) as their first childhood experience of nudity. Many were accidental (walking in on someone) and were more likely to be remembered as negative by women. Only 4.72% of women and 2% of men reported seeing nude images as part of sex education. A majority of both women (83.59%) and men (89.45%) reported that their first image of nudity was in film, video, or other mass media.[172]

The health textbooks in Finnish secondary schools emphasize the normalcy of non-sexual nudity in saunas and gyms as well as openness to the appropriate expression of developing sexuality.[173] The Netherlands also has open and comprehensive sex education beginning as early as age 4. In addition to good health outcomes, the program promoted gender equality. Young children in the Netherlands often play outdoors or in public wading pools nude.[174] Tous à Poil! (Everybody Gets Naked!), a French picture book for children, was first published in 2011 with the stated purpose of presenting a view of nudity in opposition to media images of the ideal body but instead depicting ordinary people swimming naked in the sea including a teacher and a policeman.[175] Attempts by the Union for a Popular Movement to exclude the book from schools prompted French booksellers and librarians to hold a nude protest in support of the book's viewpoint.[176] As part of a science program on Norwegian public television (NRK), a series on puberty intended for 8–12-year-olds includes explicit information and images of reproduction, anatomy, and the changes that are normal with the approach of puberty. Rather than diagrams or photos, the videos were shot in a locker room with live nude people of all ages. The presenter, a physician, is relaxed about close examination and touching of relevant body parts, including genitals. While the videos note that the age of consent in Norway is 16, abstinence is not emphasized. In a subsequent series for teens and young adults, real people were recruited to have sex on TV as counterbalance to the unrealistic presentations in advertising and porn.[177] A 2020 episode of a Danish TV show for children presented five nude adults to an audience of 11–13-year-olds with the lesson "normal bodies look like this" to counter social media images of perfect bodies.[178]

A 2009 report issued by the CDC comparing the sexual health of teens in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the United States concluded that if the US implemented comprehensive sex education similar to the three European countries there would be a significant reduction in teen pregnancies, abortions and the rate of sexually transmitted diseases, and save hundreds of millions of dollars.[179]

Nudity in the home

In 1995, Gordon and Schroeder contended that "there is nothing inherently wrong with bathing with children or otherwise appearing naked in front of them", noting that doing so may provide an opportunity for parents to provide important information. They noted that by ages five to six, children begin to develop a sense of modesty, and recommended to parents who desire to be sensitive to their children's wishes that they respect a child's modesty from that age onwards.[180] In a 1995 review of the literature, Paul Okami concluded that there was no reliable evidence linking exposure to parental nudity to any negative effect.[181] Three years later, his team finished an 18-year longitudinal study that showed, if anything, such exposure was associated with slight beneficial effects, particularly for boys.[182] In 1999, psychologist Barbara Bonner recommended against nudity in the home if children exhibit sexual play of a type that is considered problematic.[183] In 2019, psychiatrist Lea Lis recommended that parents allow nudity as a natural part of family life when children are very young, but to respect the modesty that is likely to emerge with puberty.[184]

In a 2009 article for the New York Times "Home" section, Julie Scelfo interviewed parents regarding the nudity of small children at home in situations which might include visitors outside the immediate household. The situations ranged from a three-year-old being naked at a large gathering to the use of a backyard swim pool becoming an issue when the children of disapproving neighbors participated. While the consensus was to allow kids to be kids up to the age of five, there was acknowledgment of the possible discomfort of adults who consider such behavior to be inappropriate. While opponents of child nudity referred to the danger of pedophilia, proponents viewed innocent nudity as beneficial compared to the sexualization of children in toddler beauty pageants with makeup and "sexy" outfits.[185]

-

Recreational swim in the Greenbrier River, West Virginia (1946)

-

Fountain in Israel (between 1947 and 1950)

-

Bathing in the center of East Berlin, East Germany (1958)

-

A nude family at Lake Senftenberg in East Germany (1980s)

Semi-private/semi-public nudity

Steam baths and spas

Bathing for cleanliness and recreation is a human universal, and the communal use of bathing facilities has been maintained in many cultures from varying traditional sources. When there is complete nudity, the facilities are often segregated by sex, but not always.

The sauna is attended nude in its source country of Finland, where many families have one in their home, and is one of the defining characteristics of Finnish identity.[71][186] Saunas have been adopted worldwide, first in Scandinavian and German-speaking countries of Europe,[187] with the trend in some of these being to allow both genders to bathe together nude. For example, the Friedrichsbad in Baden-Baden has designated times when mixed nude bathing is permitted. The German sauna culture also became popular in neighbouring countries such as Switzerland, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg.[b] In contrast to Scandinavia, public sauna facilities in these countries—while nude—do not usually segregate genders.[c][188] A spa in Třeboň, Czech Republic features a peat pulp bath.[190]

The sauna came to the United States in the 19th century when Finns settled in western territories, building family saunas on their farms. When public saunas were built in the 20th century, they might include separate steam rooms for men and women.[191]

In Japan, public baths (Sentō) were once common, but became less so with the addition of bathtubs in homes. Sentō were mixed gender (konyoku) until the arrival of Western influences,[47] but became segregated by gender in cities.[192] Nudity is required at Japanese hot spring resorts (Onsen).[193] Some such resorts continue to be mixed gender, but the number of such resorts is declining as they cease to be supported by local communities.[47]

In Korea, bathhouses are known as Jjimjilbang. Such facilities may include mixed-sex sauna areas where clothing is worn, but bathing areas are gender segregated; nudity is required in those areas.[194][193] Korean spas have opened in the United States, also gender separated except the bathing areas. In addition to the health benefits, a woman wrote in Psychology Today suggesting the social benefits for women and girls having real life experience of seeing the variety of real female bodies—even more naked than at a beach—as a counterbalance to the unrealistic nudity seen in popular media.[195]

In Russia, communal banyas have been used for over a thousand years, serving both hygienic and social functions. Nudity and mixed sex usage was typical for much of this history. [196] Bathing facilities in homes threatened the existence of public banyas, but social functions maintained their popularity.[197]

In Islamic countries, with many regional variations in practice, communal bathing at the hammam is primarily for men and avoids complete nudity.[citation needed]

Changing rooms

Historically, certain facilities associated with activities that require partial or complete nakedness, such as bathing or changing clothes, have limited access to certain members of the public. These normal activities are guided by generally accepted norms, the first of which is that the facilities are most often segregated by gender; however, this may not be the case in all cultures. In Islamic countries, women may not use public baths, and men must wear a waist wrapper.[198] In some traditional cultures and rural areas modern practices are limited by the belief that only the exposed parts of the body (hands, feet, face) need to be washed daily; and also by Christian and Muslim belief that the naked body is shameful and must always be covered.[199]

Changing rooms may be provided in stores, workplaces, or sports facilities to allow people to change their clothing. Some changing rooms have individual cubicles or stalls affording varying degrees of privacy. Locker rooms and communal showers associated with sports generally lacked any individual space, thus providing minimal physical privacy.

The men's locker room—which in Western cultures had been a setting for open male social nudity—is, in the 21st century United States, becoming a space of modesty and distancing between men. For much of the 20th century, the norm in locker rooms had been for men to undress completely without embarrassment. That norm has changed; in the 21st century, men typically wear towels or other garments in the locker room most of the time and avoid any interaction with others while naked. This shift is the result of changes in social norms regarding masculinity and how maleness is publicly expressed; also, open male nudity has become associated with homosexuality.[200][201] In facilities such as the YMCA that cater to multiple generations, the young are uncomfortable sharing space with older people who do not cover up.[202] The behavior in women's locker rooms and showers also indicates a generational change, younger women covering more, and full nudity being brief and rare, while older women are more open and casual.[203]

Communal showers

By the 1990s, communal showers in American schools had become "uncomfortable", not only because students were accustomed to more privacy at home, but because young people became more self-conscious based upon the comparison to mass media images of perfect bodies.[204] In the 21st century, some high-end New York City gyms were redesigned to cater to millennials who want to shower without ever being seen naked.[205] The trend for privacy is being extended to public schools, colleges and community facilities replacing "gang showers" and open locker rooms with individual stalls and changing rooms. The change also addresses issues of transgender usage and family use when one parent accompanies children of differing gender.[206]

A 2014 study of schools in England found that 53% of boys and 67.5% of girls did not shower after physical education (PE) classes. Other studies indicate that not showering, while often related to being naked with peers, is also related to lower intensity of physical activity and involvement in sports.[207]

This shift in attitudes has come to societies historically open to nudity. In Denmark, secondary school students are now avoiding showering after gym classes. In interviews, students cited the lack of privacy, fears of being judged by idealized standards, and the possibility of being photographed while naked.[208] Similar results were found in schools in Norway.[209][210]

Arts-related activities

Distinct from the nude artworks created, sessions where artists work from live models are a social situation where nudity has a long tradition. The role of the model both as part of visual art education and in the creation of finished works has evolved since antiquity in Western societies and worldwide wherever western cultural practices in the visual arts have been adopted. At modern universities, art schools, and community groups "art model" is a job, one requirement of which is to pose "undraped" and motionless for minutes, hours (with breaks) or resuming the same pose for days as the artwork requires.[211] Some have investigated the benefits of arts education including nudes as an opportunity to satisfy youthful curiosity regarding the human body in a non-sexual context.[212]

Public nudity

Attitudes toward public nudity vary from complete prohibition in Islamic countries to general acceptance, particularly in Scandinavia and Germany,[213] of nudity for recreation and at special events. Such special events can be understood by expanding the historical concept of Carnival, where otherwise transgressive behaviors are allowed on particular occasions, to include other mass nudity public events. Examples include the Solstice Swim in Tasmania (part of the Dark Mofo festival) and World Naked Bike Rides.[214]

Germany is known for being tolerant of public nudity in many situations.[215] In a 2014 survey, 28% of Austrians and Germans had sunbathed nude on a beach, 18% of Norwegians, 17% of Spaniards and Australians, 16% of New Zealanders. Of the nationalities surveyed, the Japanese had the lowest percentage, 2%.[216]

In the United States in 2012, the city council of San Francisco, California, banned public nudity in the inner-city area. This move was met by harsh resistance because the city was known for its liberal culture and had previously tolerated public nudity.[217][218] Similarly, park rangers began issuing tickets against nudists at San Onofre State Beach—also a place with long tradition of public nudity—in 2010.[219]

Naturism

Naturism (or nudism) is a subculture advocating and defending private and public nudity as part of a simple, natural lifestyle. Naturists reject contemporary standards of modesty that discourage personal, family and social nudity. They instead seek to create a social environment where individuals feel comfortable being in the company of nude people and being seen nude, either by other naturists or by the general public.[220] In contradiction of the popular belief that nudists are more sexually permissive, research finds that nudist and non-nudists do not differ in their sexual behavior.[221]

The social sciences, until the middle of the 20th century, often studied public nakedness, including naturism, in the context of deviance or criminality.[222] However, more recent studies find that naturism has positive effects on body image, self-esteem and life satisfaction.[223] The Encyclopedia of Social Deviance continues to have an entry on "Nudism",[224] but also defines "Normal Deviance" as violating social norms in a positive way, leading to social change.[225]

Nude beaches

A nude beach, sometimes called a clothing-optional or free beach, is a beach where users are at liberty to be nude. Such beaches are usually on public lands. Nude beaches may be official (legally sanctioned), unofficial (tolerated by residents and law enforcement), or illegal but so isolated as to escape enforcement.

Cultural differences

Norms related to nudity are associated with norms regarding personal freedom, human sexuality, and gender roles, which vary widely among contemporary societies. Situations where private or public nudity is accepted vary. Some people practice social nudity within the confines of semi-private facilities such as naturist resorts, while other seek more open acceptance of nudity in everyday life and in public spaces designated as clothing-optional.[226]

In Africa, there is a sharp contrast between Islamic countries where nudity is forbidden and the sub-Saharan countries that never abandoned, or are reasserting, precolonial norms that accepted nudity as natural. In contemporary rural villages, both boys and girls are allowed to play totally nude, and women bare their breasts in the belief that the meaning of naked bodies is not limited to sexuality.[227]

In Asia, the norms regarding public nudity are in keeping with the cultural values of social propriety and human dignity. Rather than being perceived as immoral or shameful, nakedness is perceived as a breach of etiquette and perhaps as an embarrassment. In China, saving face is a powerful social force. In Japan, proper behavior included a tradition of mixed gender public baths before Western contact began in the 19th century, and proper attire for farmers and other workers might be a loincloth for both men and women. In India, the conventions regarding proper dress do not apply to monks in some Hindu and Jain sects who reject clothing as worldly. In contemporary China, while maintaining the traditions of modest dress in everyday life, the use of nudity in magazine advertising indicates the effect of globalization.[228]

Western societies inherited contradictory cultural traditions relating to nudity in various contexts. The first tradition came from the ancient Greeks, who saw the naked body as the natural state and as essentially positive. The second is based upon the Abrahamic religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—which view being naked as shameful and essentially negative. The fundamental teachings of these religions prohibit public and sometimes also private nudity. The interaction between the Greek classical and later Abrahamic traditions has resulted in Western ambivalence, with nudity acquiring both positive and negative meanings in individual psychology, in social life, and in depictions such as art.[229] While public modesty prevails in more recent times, organized groups of nudists or naturists emerged with the stated purpose of regaining a natural connection to the human body and nature, sometimes in private spaces but also in public. Naturism in the United States, meanwhile, remains largely confined to private facilities, with few "clothing optional" public spaces compared to Europe. In spite of the liberalization of attitudes toward sex, Americans remain uncomfortable with complete nudity.[78]

Sexual and non-sexual nudity

The social context defines the cultural meaning of nudity that may range from the sacred to the profane. There are activities where freedom of movement is promoted by full or partial nudity. The nudity of the ancient Olympics was part of a religious practice. Athletic activities are also appreciated for the beauty of bodies in motion (as in dance), but in the post-modern media athletic bodies are often taken out of context to become purely sexual, perhaps pornographic.[230]

The sexual nature of nudity is defined by the gaze of others. Studies of naturism find that its practitioners adopt behaviors and norms that suppress the sexual responses while practicing social nudity.[231] Such norms include refraining from staring, touching, or otherwise calling attention to the body while naked.[232] However, some naturists do not maintain this non-sexual atmosphere, as when nudist resorts host sexually-oriented events.[233]

Morality

The moral ambiguity of nudity is reflected in its many meanings, often expressed in the metaphors used to describe cultural values, both positive and negative.[234]

One of the first—but now obsolete—meanings of nude in the 16th century was "mere, plain, open, explicit" as reflected in the modern metaphors "the naked truth" and "the bare facts". Naturists often speak of their nakedness in terms of a return to the innocence and simplicity of childhood. The term naturism is based upon the idea that nakedness is connected to nature in a positive way as a form of egalitarianism, that all humans are alike in their nakedness. Nudity also represents freedom: the liberation of the body is associated with sexual liberation, although many naturists tend to downplay this connection. In some forms of group psychotherapy, nudity has been used to promote open interaction and communication. Religious persons who reject the world as it is including all possessions may practice nudism, or use nakedness as a protest against an unjust world.[235]

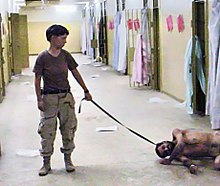

Many of the negative associations are the inverse of positive ones. If nudity is truth, nakedness may be an invasion of privacy or the exposure of uncomfortable truths, a source of anxiety. The strong connection of nudity to sex produces shame when naked in contexts where sexuality is deemed inappropriate. Rather than being natural, nakedness is associated with savagery, poverty, criminality, and death. To be deprived of clothes is punishment, humiliating and degrading.[236]

Confronted with this ambiguity, some individuals seek to resolve it by working toward greater acceptance of nudity for themselves and others. The majority of naturists go through stages during which they gradually learn a new set of values regarding the human body.[237] However, Krista Thomason notes that negative emotions including shame exist because they are functional, and that human beings are not perfect.[238]

Religious interpretations

Abrahamic religions

Among ancient cultures, the association of nakedness with sexual sin was peculiar to Abrahamic religions. In Mesopotamia and Egypt, nakedness was embarrassing due to the social connotations of low status and deprivation rather than shame regarding sexuality.[239] Nudity was also not associated with sexuality due to the prevalence of functional nudity, where clothing was removed while engaged in any activity for which it would be impractical.[240]

The original meaning of the naked body in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam was defined by the Genesis creation narrative. The meaning of this myth is inconsistent with a philosophical analysis of shame as an emotion of reflective self-assessment which is understood as a response to being seen by others, a social context that did not exist. The "original sin" was disobedience, not nakedness or awareness of sexuality, yet the response was for Adam and Eve to cover their bodies.[241] According to German philosopher Thorsten Botz-Bornstein, interpretations of Genesis have placed responsibility for the fall of man and original sin on Eve, and, therefore, all women. As a result, the nudity of women is deemed more shameful personally and corrupting to society than the nakedness of men.[242] The biblical stories of Bathsheba and Susanna place the responsibility for arousing lust in male onlookers upon the women who are bathing although they had no intent to be seen. This is in contrast to the story of Judith, who bathes publicly to seduce and later behead the enemy general Holofernes. However all three stories are based upon the belief that men are unable to control their sexuality when seeing a nude woman.[243]

Orthodox Jewish Law (Halakha) explicitly makes women responsible for maintaining the virtue of modesty (Tzniut) by covering their bodies, including their hair.[244] For men, nakedness was limited to exposure of the penis, but is not limited to public exposure, but in private as well. In late antiquity, Jews viewed with abhorrence the Greek and Roman practices of going naked and portraying male gods as naked. In any religious context, male nudity was of greater concern than female nudity because it was an offense against God. In everyday activity male nudity might be necessary, but is to be avoided. Female nudity was not an offense against God, but only about arousing the sexual passions of men, thus private or female only nudity was not immodest.[245]

Christian theology rarely addresses nudity, but rather proper dress and modesty. Western cultures adopted Greek heritage only with regard to art, the ideal nude. Real naked people remained shameful; and become human only when they cover their nakedness. In one of a series of lectures "Theology of the Body" given in 1979, Pope John Paul II said that the innocent nudity of being before the fall is regained only between loving spouses.[246] In daily life, Christianity requires clothing in public, but with great variation between and within societies as to the meaning of "public" and how much of the body is covered. Plain dress is the practice of the most conservative, generally branches of Anabaptism, requiring not only coverage from ankles to collarbone but the absence of decoration and the use of makeup. Modest dress also reinforces group identity.[247] Somewhat less strict, the Bible Methodists practice is coverage of the body from torso to thighs except in the context of marriage.[248] Mennonites may also practice modesty while wearing modern clothes, but with adaptations such as below the knee skirts and long sleeves.[247]

Finnish Lutherans practice mixed nudity in private saunas used by families and close-knit groups. While maintaining communal nudity, men and women are now often separated in public or community settings.[249] Certain sects of Christianity through history have included nudity into worship practices, but these have been deemed heretical.[51][40] There have been Christian naturists in the United States since the 1920s, but as a social and recreational practice rather than part of an organized religion.[250]

Modern practices in Islamic countries are guided by rules of modesty that vary somewhat between five schools of Islamic law, the most conservative being the Hanbali School in Saudi Arabia and Qatar, where the niqab, the garment covering the whole female body and the face with a narrow opening for the eyes, is widespread. The burqa, limited mainly to Afghanistan, also has a mesh screen which covers the eye opening.[251] Different rules apply to men, women, and children; and depend upon the gender and family relationship of others present.[252] The Sunni scholar Yusuf al-Qaradawi states that looking at the intimate parts of the body of another of either sex must be avoided. For women after puberty, the prohibition includes the entire body except the hands and face. However, hands and face may be shown only if they may be viewed without temptation. Men must cover themselves from the navel to the knees.[253] Shame dictates that the genitals should be covered even when a person is alone.[254] The dress of women must not only cover virtually the entire body, but cannot be either transparent or close-fitting to reveal the shape of the body.[255] When onlookers are close relations, prohibitions for women do not include hair, ears, neck, upper part of the chest, arms and legs.[256] The same exceptions are also made for men seeing women to whom they are proposing marriage.[257]

Asian religions

Some Hindu and Jain practitioners of asceticism, rejecting all worldly goods including clothing, are naked or wear only a loincloth.[99][100] Although overwhelmingly male, there have been female ascetics such as Akka Mahadevi who refused to wear clothing.

Public bathing for purification as well as cleanliness is part of both Shintoism and Buddhism in Japan. Purification in the bath is not only for the body, but the heart or spirit (kokoro)[258]

Legal issues

Worldwide, laws regarding clothing specify what parts of the body must be covered, prohibiting complete nudity in public except for those jurisdictions that allow nude recreation.

Specific laws may either require or prohibit religious attire (veiling) for women. In a survey using data from 2012 to 2013, there were 11 majority Muslim countries where women must cover their entire bodies in public, which may include the face. There were 39 countries, mostly in Europe, that had some prohibition of religious attire, in particular face coverings in certain situations, such as government buildings. Within Russia, laws may either require or prohibit veiling depending upon location.[259]

The brief, sudden exposure of parts of the body normally hidden from public view has a long tradition, taking several forms.

- Flashing refers to the brief public exposure of the genitals or female breasts.[260] At Mardi Gras in New Orleans flashing—an activity that would be prohibited at any other time and place—has become a ritual of long standing in celebration of Carnival. While many celebrations of Carnival worldwide include minimal costumes, the extent of nudity in the French Quarter is due to its long history as a "red light district". The ritual "disrobing" is done in the context of a performance which earns a payment, even though it is only symbolic (glass beads). Although the majority of those performing continue to be women, men (both homosexual and heterosexual) now also participate.[261]

- Mooning refers to exposure of the buttocks. Mooning opponents in sports or in battle as an insult may have a history going back to ancient Rome.[262]

- Streaking refers to running nude through a public area. While the activity may have a long history, the term originated in the 1970s for a fad on college campuses, which was initially widespread but short-lived.[263] Later, a tradition of "nude runs" became institutionalized on certain campuses, such as the Primal Scream at Harvard.