Jack Kirby: Difference between revisions

| Line 205: | Line 205: | ||

*In the Batman Animated series Etrigan the Demon allies with Batman and during a battle scene the window to KIRBY'S BAKERY is smashed. |

*In the Batman Animated series Etrigan the Demon allies with Batman and during a battle scene the window to KIRBY'S BAKERY is smashed. |

||

*The 1995 movie ''[[Crimson Tide (film)|Crimson Tide]]'' features a scene in which submarine sailors brawl over a disagreement as to whether the [[Silver Surfer]] drawn by Kirby was better than the |

*The 1995 movie ''[[Crimson Tide (film)|Crimson Tide]]'' features a scene in which submarine sailors brawl over a disagreement as to whether the [[Silver Surfer]] as drawn by Kirby was better than the version drawn by [[Jean Giraud|Moebius]]. Second-in-command Ron Hunter (played by [[Denzel Washington]]) finally announces, ''"Now, everyone who reads comic books knows that the Kirby Silver Surfer is the only true Silver Surfer. Now, am I right or wrong?"'' |

||

*Episodes late in the 2006-2007 season of the [[NBC]] superhero TV series ''[[Heroes (TV series)|Heroes]]'' include New York City scenes set at the fictional Kirby Plaza. |

*Episodes late in the 2006-2007 season of the [[NBC]] superhero TV series ''[[Heroes (TV series)|Heroes]]'' include New York City scenes set at the fictional Kirby Plaza. |

||

Revision as of 00:05, 24 March 2008

Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzberg, August 28, 1917 – February 6, 1994) was one of the most influential, recognizable, and prolific artists in American comic books, and the co-creator of such enduring characters and popular culture icons as the Fantastic Four, the X-Men, the Hulk, Captain America, and hundreds of others stretching back to the earliest days of the medium. He was also a comic book writer and editor. His most common nickname is "The King."

Historians and most comics creators acknowledge Kirby as one of the medium's greatest and most influential artists. The New York Times, in a Sunday op-ed piece written more than a decade after his death, said Kirby

created a new grammar of storytelling and a cinematic style of motion. Once-wooden characters cascaded from one frame to another — or even from page to page — threatening to fall right out of the book into the reader’s lap. The force of punches thrown was visibly and explosively evident. Even at rest, a Kirby character pulsed with tension and energy in a way that makes movie versions of the same characters seem static by comparison.[1]

His output was legendary, with one count estimating[2] that he produced over 25,000 pages, as well as hundreds of comic strips and sketches. He also produced paintings, and worked on concept illustrations for a number of Hollywood films.

He was inducted into comic books' Shazam Awards Hall of Fame in 1975.

The Jack Kirby Award for achievement in comic books was named in his honor.

Biography

Early life

Born to Jewish Austrian parents in New York City, he grew up on Suffolk Street in New York's Lower East Side Delancey Street area, attending elementary school at P.S. 20. His father, Benjamin, a garment-factory worker, was a Conservative Jew, and Jacob attended Hebrew school. Jacob's one sibling, a brother five years younger, predeceased him. After a rough-and-tumble childhood with much fighting among the kind of kid gangs he would render more heroically in his future comics (Fantastic Four's Jewish Ben Grimm was raised on rough-and-tumble Yancy Street, and was predeceased by his older brother; in addition to sharing Kirby's father's first name, his middle name is Jacob, Kirby's first name at birth). Likewise Nick Fury's backstory is modelled after Kirby's own childhood.) Kirby enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, at what he said was age 14, leaving after a week. "I wasn't the kind of student that Pratt was looking for. They wanted people who would work on something forever. I didn't want to work on any project forever. I intended to get things done."[3]

Essentially self-taught, Kirby cited among his influences the comic strip artists Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff.

The Golden Age of Comics

Art by Kirby, inks by Simon.

Per his own sometimes-unreliable memory, Kirby joined the Lincoln Newspaper Syndicate in 1936, working there on newspaper comic strips and on single-panel advice cartoons such as Your Health Comes First (under the pseudonym "Jack Curtiss"). He remained until late 1939, then worked for the movie animation company Fleischer Studios as an "inbetweener" (an artist who fills in the action between major-movement frames) on Popeye cartoons. "I went from Lincoln to Fleischer," he recalled. "From Fleischer I had to get out in a hurry because I couldn't take that kind of thing," describing it as "a factory in a sense, like my father's factory. They were manufacturing pictures."[4] Despite this, he was prepared to relocate with the studio when it moved to Florida, only to be dissuaded by his mother who refused to let him move and had him quit instead.

Around this time, "I began to see the first comic books appear."[4] The first American comic books were reprints of newspaper comic strips; soon, these tabloid-size, 10-inch by 15-inch "Comic books" began to include original material in comic-strip form. Kirby began writing and drawing such material for the comic book packager Eisner & Iger, one of a handful of firms creating comics on demand for publishers. Through that company, Kirby did what he remembers as his first comic book work, for Wild Boy Magazine.[5] This included such strips as the science fiction adventure The Diary of Dr. Hayward (under the pseudonym "Curt Davis"), the Western crimefighter strip Wilton of the West (as "Fred Sande"), the swashbuckler strip "The Count of Monte Cristo" (again as "Jack Curtiss"), and the humor strips Abdul Jones (as "Ted Grey)" and Socko the Seadog (as "Teddy"), all variously for Jumbo Comics and other Eisner-Iger clients. Kirby was also helpful beyond his artwork when he once frightened off a mobster who was strongarming Eisner for their building's towel service.

Kirby moved on to comic-book publisher and newspaper syndicator Fox Feature Syndicate, earning a then-reasonable $15 a week salary. He began exploring superhero narrative with the comic strip The Blue Beetle (January–March 1940), starring a character created by the pseudonymous Charles Nicholas, a house name that Kirby retained for the three-month-long strip.

Simon & Kirby

During this time, Kirby met and began collaborating with cartoonist and Fox editor Joe Simon, who in addition to his staff work continued to freelance. Speaking at a 1998 Comic-Con International panel in San Diego, California, Simon recounted the meeting:

I had a suit and Jack thought that was really nice. He'd never seen a comic book artist with a suit before. The reason I had a suit was that my father was a tailor. Jack's father was a tailor too, but he made pants! Anyway, I was doing freelance work and I had a little office in New York about ten blocks from DC's and Fox [Feature Syndicate]'s offices, and I was working on Blue Bolt for Funnies, Inc. So, of course, I loved Jack's work and the first time I saw it I couldn't believe what I was seeing. He asked if we could do some freelance work together. I was delighted and I took him over to my little office. We worked from the second issue of Blue Bolt...[6]

and remained a team across the next two decades. In the early 2000s, original art for an unpublished, five-page Simon & Kirby collaboration titled "Daring Disc", which may predate the duo's Blue Bolt, surfaced. Simon published the story in the 2003 updated edition of his autobiography, The Comic Book Makers.[7]

After leaving Fox and landing at pulp magazine publisher Martin Goodman's Timely Comics (the future Marvel Comics), the new Simon & Kirby team created the seminal patriotic hero Captain America in late 1940. Their dynamic perspectives, groundbreaking use of centerspreads, cinematic techniques and exaggerated sense of action made the title an immediate hit and rewrote the rules for comic book art. Simon and Kirby also produced the first complete comic book starring Captain Marvel for Fawcett Comics.

Captain America became the first and largest of many hit characters the duo would produce. The Simon & Kirby name soon became synonymous with exciting superhero comics, and the two became industry stars whose readers followed them from title to title. A financial dispute with Goodman led to their decamping to National Comics, one of the precursors of DC Comics, after ten issues of Captain America. Given a lucrative contract at their new home, Simon & Kirby took over the Sandman in Adventure Comics, and scored their next hits with the "kid gang" teams the Boy Commandos and the Newsboy Legion, and the superhero Manhunter.

Kirby married Rosalind "Roz" Goldstein (September 25, 1922–December 22, 1998) on May 23, 1942. The couple would have four children: Susan, Neal, Barbara and Lisa. The same year that he married, he changed his name legally from Jacob Kurtzberg to Jack Kirby. The couple was living in Brighton Beach, Brooklyn, when Kirby was drafted into the U.S. Army in the late autumn of 1943. Serving with the Third Army combat infantry, he landed in Normandy, on Omaha Beach, 10 days after D-Day.

As superhero comics waned in popularity after the end of World War II, Kirby and his partner began producing a variety of other genre stories. They are credited with the creation of the first romance title, Young Romance Comics at Crestwood Publications, also known as Prize Comics. In addition, Kirby and Simon produced crime, horror (notably Black Magic), western and humor comics.

After Simon

The Kirby & Simon partnership ended amicably in 1955 with the failure of their own Mainline Publications. Kirby continued to freelance. He was instrumental in the creation of Archie Comics' The Fly and The Double Life of Private Strong reuniting briefly with Joe Simon. He also drew some issues of Classics Illustrated.

For DC Comics, then known as National Comics, Kirby co-created with writers Dick and Dave Wood the non-superpowered adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown in Showcase #6 (Feb. 1957), while also contributing to such anthologies as House of Mystery. In 30 months at DC, Kirby drew slightly more than 600 pages, which included 11 Green Arrow stories in World's Finest Comics and Adventure Comics that, in a rarity, Kirby inked himself.[8] He also began drawing a newspaper comic strip, Sky Masters of the Space Force, written by the Wood brothers and initially inked by the unrelated Wally Wood.

Kirby left National Comics after a contractual dispute in which editor Jack Schiff, who had been involved in getting Kirby and the Wood brothers the Sky Masters contract, claimed he was due royalties from Kirby's share of the strip's profits. Schiff sued Kirby and was successful at trial.[9][10]

Stan Lee and Marvel Comics

Kirby also worked for Marvel, on the cusp of the company's evolution from its 1950s incarnation as Atlas Comics, beginning with the cover and the seven-page story "I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers" in Strange Worlds #1 (Dec. 1958).[11] Kirby would draw across all genres, from romance to Western (the feature "Black Rider") to espionage (Yellow Claw), but made his mark primarily with a series of monster, horror and science fiction stories for the company's many anthology series, such as Amazing Adventures, Strange Tales, Tales to Astonish and Tales of Suspense. His bizarre designs of powerful, unearthly creatures proved a hit with readers. Then, with Marvel editor-in-chief Stan Lee, Kirby began working on superhero comics again, beginning with The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961). The landmark series became a hit that revolutionized the industry with its comparative naturalism and, eventually, a cosmic purview informed by Kirby's seemingly boundless imagination — one coincidentally well-matched with the consciousness-expanding youth culture of the 1960s.

For almost a decade, Kirby provided Marvel's house style, co-creating/designing many of the Marvel characters and providing layouts for new artists to draw over. Artist Gil Kane summed up Kirby's influence in the following manner:

Everybody recognised Jack's contribution to comics generall and to Marvel specifically, in the same way they recognise that God created the heavens and the Earth... it wasn't merely that Jack conceived most of the characters that are being done, but more than that - Jack's point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field... In order to broaden the scope of their publishing, what they managed to do was to take Jack and use him as a primer. They [Marvel] would get artists, regardless of whether they had done romance or anything else and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby. So, whether it was John Romita, whether it was anyone who ultimately joined the company, Jack was used as the yardstick by which they could measure their own progress. Jack was like the Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That's what was told to me... it was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view.[12]

Highlights besides the Fantastic Four include Thor, the Incredible Hulk, Iron Man, the original X-Men, the Silver Surfer, Doctor Doom, Galactus, The Watcher, Magneto, Ego the Living Planet, the Inhumans and their hidden city of Attilan, and the Black Panther — comics' first known Black superhero — and his African nation of Wakanda. Simon & Kirby's Captain America was also incorporated into Marvel's continuity.

In 1968 and 1969, Joe Simon was involved in litigation with Marvel Comics over the ownership of Captain America, initiated by Marvel after Simon registered the copyright renewal for Captain America in his own name. According to Simon, Kirby agreed to support the company in the litigation and, as part of a deal Kirby made with publisher Martin Goodman, signed over to Marvel any rights he might have had to the character.[9]

Kirby continued to expand the medium's boundaries, devising photo-collage covers and interiors, developing new drawing techniques such as the method for depicting energy fields now known as "Kirby Dots," and other experiments. Yet he grew increasingly dissatisfied with working at Marvel. There have been a number of reasons given for this dissatisfaction, including resentment over Stan Lee's increasing media prominence, a lack of full creative control, anger over breaches of perceived promises by publisher Martin Goodman, and frustration over Marvel's failure to credit him specifically for his story plotting and for his character creations and co-creations. He began to both script and draw some secondary features for Marvel, such as "The Inhumans" in Amazing Adventures and horror stories for the anthology title Chamber of Darkness, and received full credit for doing so; but he eventually left the company in 1970 for rival DC Comics, under editorial director Carmine Infantino.

After leaving Marvel, Kirby also took up oboe playing. He became quite prolific and enjoyed small success playing at lounges and night clubs. Columbia Records offered him a contract, but he snubbed it in order to continue his work in comics[citation needed].

Later life and career

The New Gods

Art by Kirby & Don Heck.

Kirby returned to DC in the early 1970s, under an arrangement that gave him full creative control as editor, writer and artist. He produced a series of inter-linked titles under the blanket sobriquet “The Fourth World” including a trilogy of new titles, New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People, as well as the Superman title, Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen. Kirby picked the book because the series was without a stable creative team and he did not want to cost anyone a job.[13] The central villain of the Fourth World series, Darkseid, and some of the Fourth World concepts, appeared in Jimmy Olsen before the launch of the other Fourth World books, giving the new titles greater exposure to potential buyers.

Kirby later produced other DC titles such as OMAC, Kamandi, The Demon, and, together with former partner Joe Simon for one last time, a new incarnation of the Sandman. Several characters from this period have since become fixtures in the DC Universe, including the demon Etrigan and his human counterpart Jason Blood; Scott Free (Mister Miracle), and the cosmic villain Darkseid.

Kirby then returned to Marvel Comics where he both wrote and drew Captain America and created the series The Eternals, which featured a race of inscrutable alien giants, the Celestials, whose behind-the-scenes intervention influenced the evolution of life on Earth. Kirby’s other Marvel creations in this period include Devil Dinosaur, Machine Man, and an adaptation and expansion of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey. He also wrote and drew The Black Panther and did numerous covers across the line.

Still dissatisfied with Marvel’s treatment of him, and their refusal to provide health and other employment benefits, Kirby left Marvel to work in animation, where he did designs for Turbo Teen, Thundarr the Barbarian and other animated television series. He also worked on The Fantastic Four cartoon show, reuniting him with scriptwriter Stan Lee. He illustrated an adaptation of the Walt Disney movie The Black Hole for Walt Disney’s Treasury of Classic Tales syndicated comic strip in 1979-80.

Kirby vs Marvel

In 1985, screenwriter and comic-book historian Mark Evanier, a Kirby friend and former assistant, revealed to The Comics Journal that not only had thousands of pages of Kirby’s artwork had been lost by Marvel Comics, but that the remaining pages (just 88 "out of a total of more than 8,000") were effectively being held hostage by the company.[14] This issue - the return of pages legally and morally owned by the artist - became the subject of a dispute between Kirby and Marvel, in large part because Kirby was singled out for specialist treatment. Prior to 1973 (when rival comics company DC acknowledged the "insensitive" handling - and often destruction - of original artwork, and began to work towards returning remaining pages and compensating artists whose work did not remain in storage), artwork was not routinely returned to the artists who had created it. Artwork from comics' earliest days was regularly destroyed, lost or arbitrarily given away by all companies who placed little or no value in it.[15] Largely through the lobbying of groups fronted by Neal Adams working for creator's rights and fair treatment, this practice began to change, and artwork was more regularly stored than destroyed - but still not returned to the artists who had drawn it. After the example set by DC in starting to return current and backlogged art pages, many companies began to move towards returning pages, typically requiring the artists to sign a waiver releasing themselves from all rights related to the artwork, and acknowledging it as the sole property of the company for which it was created.[16] (After 1978, copyright law changed, and "work for hire" arrangements were required to be defined in writing.[17] This caused a dilemma for many comics companies, whose livelihoods relied on "work for hire" practices, but who then found their properties under potential fire. To get around this, retroactive agreements were drawn up for - particularly - artists to sign. It was one such agreement presented to Kirby in 1979 that precipitated his departure from Marvel. With the move towards returning artwork to artists, the comics companies hit upon the idea of tying these returns to a recipt/contractual release form, whereby the artists acknowledged upon receipt of their original pages that the artwork was created under "work for hire" guidelines, and that they thereafter waived all rights to its creation in favour of the companies. These releases were widely accepted, but also rankled with some industry professionals, such as Neal Adams and Mike Ploog in particular.[18])

Although all artists were required by Marvel to sign release forms in return for their pages, Kirby was singled out with a much more detailled form than any other artist - four pages to the 'normal' one. This form required not only the standard disclaimour of non-ownership of the ideas and characters created under "work for hire" (which Kirby regularly stated that he was reasonably happy to sign), but disbarred him from ever supporting his own or others' claims of any sort against Marvel, named him solely as custodian rather than owner of his pages (thereby refusing him the right to exhibit them or sell them - which to this day forms a common, and sometimes necessary, supplimentary income for artists) among other strict - and outrageous - stipulations. Furthermore, while naming just 88 pages (The Comics Journal estimated this to be just over 1% of his total output - Frank Miller suggested less than 1%), the release form Marvel attempted to pressure Kirby into signing stated that:

- "The Artist acknowledges that he or she has no claim or right to the ownership, possession or custody, or any other right [to] any other or different artwork or material presently in Marvel's possession, custody or control."[19]

In other words, Marvel appeared not only to be singling out Kirby to stricter and more prohibitive sanctions (based solely on the key nature of his contributions, which did not merely form the backbone of the company, but almost the entire body of its artistic output both by creation and inspiration) over the return of any pages of his original artwork, but also expecting him to relinquish all claims to the thousands of "missing" pages - many more of which, it later transpired were in Marvel's warehouses. Kirby necessarily baulked at the agreement which was being pressured on him, and refused to sign. After details were leaked to The Comics Journal, editor Gary Groth spearheaded the championing of Kirby's moral and legal rights both to the full return of his artwork, and to the downgrading of the sanctions Marvel was trying to force upon him. Although Marvel cited the need for such language, intimating that Kirby had threatened to persue full ownership of some of his characters, this claim was denied by Kirby, and mitigated by Evanier as reciprocal behaviour:

- "They kept threatening him and he kept threatening them," said Evanier, "[i]t was the only way he could get their attention. And somebody at Marvel over-reacted."[20]

Although some creators declined to stand in support of Kirby's battle, (Groth suggests their reasons included the need not to antagonise the big companies who held the promise of their livelihoods, resentment, apathy and non-comprehension as being among the key reasons), many more signed The Comics Journals circulated petition (printed in The Comics Journal #110, and reprinted in The Comics Journal Library: Jack Kirby) in his support. Frank Miller wrote persuasively in The Comics Journal #5, Neal Adams continued to fight for creators' rights, and other notable individuals also leant their weight to the issue, with Will Eisner writing an open letter to TCJ, alongside one from DC's Jenette Kahn, Dick Giordano and Paul Levitz imploring Marvel to see legal and moral sense. Eventually, in 1987, Marvel downgraded their request for the mammoth release form, and even amended the 'normal' artist's short form to better address some of Kirby's specific concerns. Kirby ultimately received back from Marvel the 1,900-2,100 pages of his original art that remained in its possession (the other thousands having been forever misplaced, and routinely given away or stolen - many pages surfaced on the collector's market before Kirby had any returned to him), and Kirby acknowledged formally that the copyright to the characters he had created and co-created for Marvel were their property.

The disposition of Kirby’s early art for Fawcett, and numerous other companies has remained uncertain, although DC made a concerted effort in the mid-to-late 70s to return all artwork in their possession, and compensate artists for that which had been lost, stolen or destroyed.

Pacific Comics and Topps' "Kirbyverse"

In the early 1980s, Pacific Comics, a new, non-newsstand comic book publisher, made a then-groundbreaking deal with Kirby to publish his series Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers: Kirby would retain copyright over his creation and receive royalties on it. This, together with similar actions by other “independents” such as Eclipse Comics, helped establish a precedent for other professionals and end the monopoly of the “work for hire” system, wherein comics creators, even freelancers, had owned no rights to characters they created.

Kirby also retained ownership of characters used by Topps Comics beginning in 1993, for a set of series in what the company dubbed "The Kirbyverse." These titles were dervied mainly from designs and concepts that Kirby had kept in his files, some intended initially for the by-then-defunct Pacific Comics, and then licensed to Topps for what would become the Jack Kirby's Secret City Saga mythos. Former Marvel editor-in-chief Roy Thomas wrote the main title, with artwork from many other of Marvel's older generation of artists, including Walt Simonson and Steve Ditko on Secret City Saga itself. Kirby contributed 8 pages (thought to be file-pages, and drawn up to twenty years previously) to the launch of linked title Satan's Six, alongside pages by writer Tony Isabella, penciler John Cleary and inker Armando Gil.

Other "Kirbyverse" titles included:

- Bombast, by Thomas, Gary Friedrich, Dick Ayers & John Severin)

- Captain Glory, by Thomas and Ditko

- Jack Kirby's TeenAgents, by Kurt Busiek, Neil Vokes and John Beatty

- Jack Kirby's Silver Star, by Busiek, James W. Fry III and Terry Austin

- NightGlider, by Thomas, Gerry Conway and Don Heck

- Victory, by Busiek, Keith Giffen and Jimmy Palmiotti

Kirby died at age 76 of heart failure in his Thousand Oaks, California home.

Awards and honors

Jack Kirby received a great deal of recognition over the course of his career, including the 1967 Alley Award for Best Pencil Artist. The following year he was runner-up behind Jim Steranko. His other Alley Awards were:

- 1963: Favorite Short Story - "The Human Torch Meets Captain America,", by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, Strange Tales #114

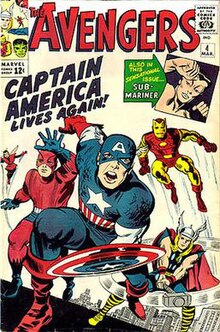

- 1964: Best Novel - "Captain America Joins the Avengers", by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, from The Avengers #4

- 1964: Best New Strip or Book - "Captain America", by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, in Tales of Suspense

- 1965: Best Short Story - "The Origin of the Red Skull", by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, Tales of Suspense #66

- 1966: Best Professional Work, Regular Short Feature - "Tales of Asgard" by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, in The Mighty Thor

- 1967: Best Professional Work, Regular Short Feature - (tie) "Tales of Asgard" and "Tales of the Inhumans", both by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, in The Mighty Thor

- 1968: Best Professional Work, Best Regular Short Feature - "Tales of the Inhumans", by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby, in The Mighty Thor

- 1968: Best Professional Work, Hall of Fame - Fantastic Four, by Stan Lee & Jack Kirby; Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D., by Jim Steranko[21]

Kirby won a Shazam Award for Special Achievement by an Individual in 1971 for his "Fourth World" series in Forever People, New Gods, Mister Miracle, and Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen. He was inducted into the Shazam Awards Hall of Fame in 1975.

His work was honored posthumously with the 1998 Harvey Award for Best Domestic Reprint Project, for Jack Kirby's New Gods by Jack Kirby, edited by Bob Kahan.

The Jack Kirby Awards and Jack Kirby Hall of Fame were named in his honor. With Will Eisner, Robert Crumb, Harvey Kurtzman, Gary Panter and Chris Ware, Kirby was among the artists honored in the exhibition "Masters of American Comics" at the Jewish Museum in New York City, New York, from Sept. 16, 2006 to Jan. 28, 2007.

On 27 July 2007, the U.S. Post Office released a full-sheet pane of Marvel Super Heroes. Ten of the stamps are portraits of individual Marvel characters and the other 10 stamps depict individual Marvel Comic book covers. According to the credits printed on the back of the pane, Jack Kirby's artwork is featured on: Captain America, The Thing, Silver Surfer, Amazing Spider-Man #1, The Incredible Hulk #1, Captain America #100, X-Men #1, and Fantastic Four #3.[1][22]

Legacy

The rooftop fighting and urban action were common in Kirby's superhero comics. They were drawn from Kirby's Depression-era youth on New York’s Lower East Side. In an interview, Kirby related that the conflict among rival gangs was incessant. The fighting was often staged up and down the tenement fire escapes, as well as in running battles across the neighborhood rooftops.[1]

The most imitated aspect of Kirby's work has been his exaggerated perspectives and dynamic energy. Less easy to imitate have been the expressive body language of his characters, who embrace each other and charge into everything from battle to pancakes with unselfconscious exuberance; and such constantly forward-looking innovations as the then cutting-edge photomontages he often used. The "Kirby Crackle" is the often imitated technique of visually depicting crackling energy using an arrangement of black dots. He (along with fellow Marvel creator Steve Ditko) pioneered the use of visible minority characters in comic books, and Kirby co-created the first black superhero at Marvel (the African prince the Black Panther) and created DC's first two black superheroes: Vykin the Black in The Forever People #1 (March 1971) and the Black Racer in The New Gods #3 (July 1971).

Kirby’s daughter, Lisa Kirby, announced[citation needed] in early 2006 that she and co-writer Steve Robertson, with artist Mike Thibodeaux, plan to publish via the Marvel Comics Icon imprint, a six-issue miniseries, Jack Kirby’s Galactic Bounty Hunters, featuring characters and concepts created by her father.

Comics historian and Kirby friend Mark Evanier wrote in February 2007 that his long-in-progress Kirby biography would be broken into at least two books, with the first of these to be an art book, Kirby: King of Comics, scheduled for publication October 2007 by publisher Harry N. Abrams.[23]

Several Kirby images are among those on the "Marvel Super Heroes" set of commemorative stamps issued by the U.S. Postal Service in 2007.[24]

Homages

This article contains a list of miscellaneous information. (August 2007) |

- In the episode "The Forever War" of the 1998-1999 Fox Kids animated television series The Silver Surfer, an alien general offers the Surfer a beverage "made from the finest grapes in the Kirby Cluster."

- Jacob Krigstein, a character in The Authority comic books, is inspired by Jack Kirby.

- Rock group Monster Magnet referenced Kirby's cultural impact in their song, "Melt", which includes the lyrics, "I was thinking how the world should have cried/On the day Jack Kirby died."

- Jazz percussionist Gregg Bendian's group Interzone recorded a tribute album, Requiem for Jack Kirby, in 2001.

- In Fantastic Four #511 (May 2004), when the team went to Heaven, God — depicted as an artist sitting at a drawing board — closely resembled Jack Kirby, the characters' co-creator.

- The mid-1980s independent comic Boris the Bear satirized the conflict between Kirby and Marvel Comics over the rights to Kirby's creations. The eponymous Boris was given the "Cosmic Can Opener of Kir-By" with instructions to right the wrongs done against an entity known as "The King". Boris confronts "Jim Spouter" (a parody of Jim Shooter, then editor-in-chief at Marvel), who sets The King's own creations against Boris. Spouter, eventually defeated sets off in a huff to create "the "Phew Universe", over which The King would have no control.

- In the animated television series, Superman: The Animated Series, the supporting character Dan Turpin, created by Kirby in the comic book New Gods, is modeled visually after Kirby. Episodes #38-39, titled "Apokolips Now," were dedicated to Kirby's memory.

- The 1986 comic Donatello #1, a one shot centering around the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles character Donatello told the story of "Kirby and the Warp Crystal". It featured a character, based on Jack Kirby, whose drawings came to life. When Donatello goes into this artist's fantasy world, he finds characters based on the New Gods. The comic was made into an episode of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles 2003 animated series, "The King".

- Also, in a proposal for a character in the fourth live action TMNT movie (which was never produced), a fifth Turtle named Kirby was designed, who was named after Jack.[25]

- In the fourth volume of Mirage's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles there is a hospital called Kurtzburg Memorial Hospital which caters specifically to super beings, mutants and other special cases. It is said in one issue that some of the super beings refer to Kurtzburg as the "father of us all".

- In Kurt Busiek's comic-book series Astro City, many Kirby references and tributes appear, such as a mountain called Mount Kirby, and the character Silver Agent, who a pastiche of Captain America, the Guardian, and Silver Star.

- Alan Moore's final storyline in Supreme: The Return features a character known as King, an inhabitant of Idea Space, who is clearly modeled after Kirby and is heralded by Kirby dots. The storyline features tributes to characters Kirby created or had a hand in defining, such as the Newsboy Legion, Guardian, the New Gods, and Doctor Doom.

- In the series Mage one of the supporting characters is named "Kirby Hero".

- The look of the adult swim animated television series Minoriteam is an homage to Kirby's art style. He is credited as "The King" in the show's end credits.

- In the Batman Animated series Etrigan the Demon allies with Batman and during a battle scene the window to KIRBY'S BAKERY is smashed.

- The 1995 movie Crimson Tide features a scene in which submarine sailors brawl over a disagreement as to whether the Silver Surfer as drawn by Kirby was better than the version drawn by Moebius. Second-in-command Ron Hunter (played by Denzel Washington) finally announces, "Now, everyone who reads comic books knows that the Kirby Silver Surfer is the only true Silver Surfer. Now, am I right or wrong?"

- Episodes late in the 2006-2007 season of the NBC superhero TV series Heroes include New York City scenes set at the fictional Kirby Plaza.

- Kirby appeared in an episode of Sabrina, the Animated Series, in which he is idolized by Sabrina's friend Harvey. Harvey meets "Jack" at a comic book convention.

- He appeared in an episode of the TV series "The Incredible Hulk" as a sketch artist at a police station. He does a sketch of the Hulk as described by an eyewitness, and of course the drawing he does looks like one of his early illustrations of the character.

- In the Marvel title She-Hulk, the titular character is employed in her civilian identity by the law firm Goodman, Lieber, Kurtzberg & Holliway, Kurtzburg being the birth surname of Jack Kirby.

- In the 2003 film Daredevil, a forensic analyst by the name of Jack Kirby is portrayed by Daredevil comic author Kevin Smith.

Quotes

Al Williamson: "If you told me or most of my buddies to draw fifty spaceships, they'd all look like they were built in the same plant. If Jack drew fifty spaceships, they'd look like they were built by fifty different alien races."[26]

Joe Simon: "My favorite artist was Lou Fine. He was also Jack Kirby's favorite artist. I know that Jack was a fan of and greatly influenced by Fine’s work."[27]

Selected bibliography

Marvel

- Captain America Comics (Golden Age) #1–10 (1941-1942)

- Various issues of "pre-superhero Marvel" science-fiction/fantasy stories in Amazing Adventures, Journey into Mystery, Strange Tales, Tales of Suspense, Tales to Astonish, Strange Worlds and World of Fantasy (1958 to early 1960s)

- Fantastic Four #1–102 (1961-1970)

- Incredible Hulk #1–5 (1962-1963)

- X-Men #1–17 + Annual 1 (1963-1970)

- Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos #1–7 (1963-1964)

- Avengers #1–8 (1963-1964), #14–17 (1965)

- The Mighty Thor #126–177,179 (1966-70; continued from Journey into Mystery)

- Captain America (modern) #100–109 (1968-1969; continued from Tales of Suspense), #193–214 (1976-1977)

- The Eternals #1–19 (1976-1978)

- The Black Panther #1–12 (1977-1978)

- Devil Dinosaur #1–9 (1978)

- Machine Man #1–9 (1978)

- 2001: A Space Odyssey (comics) #1–10 (1976)

DC

- Challengers of the Unknown #1–8 (May 1958 - July 1959)

- Adventure Comics #250–256 (July 1958 - January 1959)

- World's Finest #96–99 (September 1958 - February 1959)

- Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #133–148 (1970-1972)

- Forever People #1–11 (1971-1972)

- New Gods #1–11 (1971-1972)

- Mister Miracle #1–18 (1971-1974)

- The Demon #1–16 (1972-1974)

- Kamandi: The Last Boy on Earth #1–40 (1972-1976)

- The Sandman #1–6 (1974-1976)

- OMAC #1–8 (1974)

- Justice, Inc. #2–4 (July-November 1975)

- 1st Issue Special #1, 5-6 (April, Aug.-Sept. 1975)

Audio

- Audio of Merry Marvel Marching Society record, including voice of Jack Kirby

Footnotes

- ^ a b c The New York Times (August 26, 2007): "Editorial Observer: Jack Kirby, a Comic Book Genius, Is Finally Remembered", by Brent Staples Cite error: The named reference "nyt2007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Jack "The King" Kirby". Atlas Tales. ©2003-2007. Retrieved February 14, 2008.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Interview, The Comics Journal #134 (Feb. 1990), reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 22

- ^ a b The Comics Journal 1990 interview, p. 24

- ^ Interview, The Nostalgia Journal #30 (Nov. 1976), reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 3

- ^ "More Than Your Average Joe" (excerpts from Joe Simon's panels at 1998 Comi-Con International), Jack Kirby Collector #25 (Aug. 1999)

- ^ "The First Simon and Kirby Story?", Hoohah! (no date)

- ^ Mark Evanier, Introduction, The Green Arrow by Jack Kirby (DC Comics, New York, 2001, ISBN 6194123064): "All were inked by Jack with the aid of his dear spouse, Rosalind. She would trace his pencil work with a static pen line; he would then take a brush, put in all the shadows and bold areas and, where necessary, heavy-up the lines she'd laid down. (Jack hated inking and only did it because he needed the money. After departing DC this time, he almost never inked his own work again.)"

- ^ a b Simon, Joe, with Jim Simon. The Comic Book Makers (Crestwood/II, 1990) ISBN 1-887591-35-4; reissued (Vanguard Productions, 2003) ISBN 1-887591-35-4

- ^ Ro, Ronin. Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution. (Bloomsbury, 2004)

- ^ Kirby had previously returned to freelance on five issues cover-dated Dec. 1956 and Feb. 1957, but did not stay. They were Astonishing #56 (4 pp.), Strange Tales of the Unusual #7 (4 pp.), Quick-Trigger Western #16 (5 pp.), and Yellow Claw #2-3 (19 pp. each).

- ^ Gil Kane, speaking at a forum on July 6, 1985 at the Dallas Fantasy Fair. As quoted in:Groth, Gary (1985). The Comics Journal Library: Jack Kirby. Fantagraphics. ISBN 1560974346.

{{cite book}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Evanier, Mark. "Afterword." Jack Kirby's Fourth World Omnibus: Volume 1, New York: DC Comics, 2007.

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 89-94

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 89-94

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 89-94

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 90

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 90

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 89-94

- ^ "Kirby and Goliath: An Overview" by Michael Dean, reprinted in The Comics Journal Library, Volume One: Jack Kirby (2002) ISBN 1-56097-466-4, p. 93

- ^ Mark Hanerfeld, who counted the votes, first listed Nick Fury, Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. as the winner. Later, he noticed that he had counted votes for a) "Fantastic Four by Jack Kirby", b) "Fantastic Four by Stan Lee", and c) "Fantastic Four by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby", separately. Had they been counted as one feature, these votes combined would have given the Fantastic Four the victory.

- ^ USPS - The 2007 Commemorative Stamp Program

- ^ News from Me (column of Feb. 6, 2007): "King-Sized Announcement", by Mark Evanier

- ^ "Postal Service Previews 2007 Commemorative Stamp Program" (Oct. 25, 2006 press release)

- ^ Kevin Eastman's Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles Artobiography, ISBN 1882931858

- ^ Williamson, quoted in column News from Me (Aug. 28, 2006): "Happy Jack Kirby Day", by Mark Evanier

- ^ Comicartville Library: "Lou Fine", by Jon Berk (no date)

References

- Jack Kirby: The TCJ Interviews. Milo George, Ed. (Fantagraphics Books, Inc., 2001). ISBN 1-56097-434-6

- POV Online: "Jack Kirby", by Mark Evanier (includes Jack Kirby FAQ)

- POV Online (Jan. 9, 1998)

- The Jack Kirby Collector #10 (Interview with Roz Kirby)

- Ro, Ronin. Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution. (Bloomsbury, 2004). ISBN 1-58234-345-4

- The Unofficial Handbook of Marvel Comics Creators

- Appendix to the Handbook of the Marvel Universe: Jack Kirby

- The Pitch April 19, 2001: "Custody Battle: Marvel Comics isn't going to give up Captain America without a fight", By Robert Wilonsky

- Official Joe Simon site

- Lambiek Comiclopedia: Joe Simon