Raccoon: Difference between revisions

Undid rev. by 99.234.89.13 (talk) The article is not the talk page; preying on != self defense; vicious is POV |

|||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

=== Dousing === |

=== Dousing === |

||

Raccoons sample food and other objects with their front paws to get a picture of it and to remove unwanted parts. In addition, it increases the tactile sensibility of their paws when the callus is softened underwater.<ref>Hohmann, p. 55; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> Captive raccoons sometimes carry their food to a watering hole to “wash”, or douse, it before eating it; a behavior not observed in the wild.<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, pp. 56–57</ref> [[Natural history|Naturalist]] [[Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon]] (1707–1788) believed that raccoons do not have adequate [[salivary gland]]s to moisten food, |

Raccoons sample food and other objects with their front paws to get a picture of it and to remove unwanted parts. In addition, it increases the tactile sensibility of their paws when the callus is softened underwater.<ref>Hohmann, p. 55; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> Captive raccoons sometimes carry their food to a watering hole to “wash”, or douse, it before eating it; a behavior not observed in the wild.<ref>Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, pp. 56–57</ref> [[Natural history|Naturalist]] [[Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon]] (1707–1788) believed that raccoons do not have adequate [[salivary gland]]s to moisten food, which is definitely incorrect.<ref>Holmgren, p. 70; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> Captive raccoons douse their food more frequently, when a watering hole with a ground similar to a stream bottom is not further away than 3.0 m (10 ft).<ref>MacClintock, p. 57</ref> The widely accepted theory that dousing is a [[vacuum activity]] to mimic foraging at shores for aquatic foods is supported by the observation that such foods are doused more frequently.<ref>Hohmann, pp. 44–45; Lagoni-Hansen, pp. 41–42; MacClintock, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 7</ref> Cleaning dirty food does not seem to play a role for “washing”.<ref>MacClintock, p. 57</ref> Observations that even wild raccoons may dunk very dry food are opposed by other experts.<ref>Holmgren, p. 22 (pro); Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41 (contra)</ref> |

||

=== Reproduction === |

=== Reproduction === |

||

Revision as of 23:25, 16 August 2008

| Raccoon | |

|---|---|

| |

| A raccoon in Birch State Park, Fort Lauderdale, Florida | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. lotor

|

| Binomial name | |

| Procyon lotor | |

| |

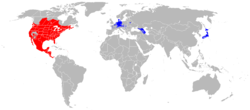

| Native range in red, feral range in blue. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ursus lotor Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The raccoon (Procyon lotor), also known as common raccoon,[1] North American raccoon,[2] northern raccoon[3] and colloquially coon,[4] is a medium-sized mammal native to North America. Raccoons are now also distributed across the European mainland and the Caucasus region, as a result of escapes from fur farms and deliberate introductions in the mid-20th century. Their original habitats are deciduous and mixed forests, but due to their adaptability they have extended their range not only to mountain areas and coastal marshes, but also to urban areas, where some house owners consider them to be pests.

With a body length between 41 and 71 cm (16.1–28.0 in) and a weight between 3.9 and 9.0 kg (8.6–19.8 lb), the raccoon is the largest procyonid. Two of its most distinctive characteristics besides its good memory are the facial mask and the extremely sensitive front paws; features dealt with in the mythology of several Native American tribes. The diet of the omnivorous and usually nocturnal raccoon consists of about 40% of invertebrates, 33% of plant foods and 27% of vertebrates. Captive raccoons sometimes douse their food before eating it, what is most likely a vacuum activity to mimic foraging at shores.

Thought to be a loner in the past, there is now evidence that raccoons show a gender-specific social behavior. Often, related females share a common area and unrelated males live together in small groups up to four animals to sustain their position during the mating season. Home range sizes may lie anywhere from 0.03 km² for females in cities to 49.5 km² for males in prairies. After a gestation period of about 65 days, two to five young are born in spring, which are subsequently raised by their mother until dispersion in late fall. Although raccoons can get as old as 16 years, their average life expectancy in the wild is only 1.8 to 3.1 years. Hunting and traffic accidents are the two most important causes of death in many areas.

Taxonomy

Nomenclature

The word raccoon is derived from the Algonquin word ahrah-koon-em—other transcripts exist—which was the pronunciation used by Chief Powhatan and his daughter Pocahontas for the animal, meaning “[the] one who rubs, scrubs and scratches with its hands”.[5] Similarly, Spanish colonists adopted the Spanish word [mapache] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) from the Nahuatl word mapachitli of the Aztecs, meaning “[the] one who takes everything in its hands”.[6] In many languages, the raccoon is named for its characteristic dousing behavior in conjunction with that language's term for bear, for example [Waschbär] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in German, [orsetto lavatore] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Italian and araiguma (洗熊) in Japanese. The colloquial abbreviation coon is used in words like coonskin for fur clothing and in phrases like old coon as self-designation of trappers.[7]

In the first decades after its discovery by the members of the expedition of Christopher Columbus, who was also the first person ever to leave a written record about the species, the raccoon was thought to be related to many different species by early taxonomists, including dogs, cats, badgers and especially bears.[8] One of them was Carolus Linnaeus who placed the raccoon in the genus Ursus, first as Ursus cauda abrupta (“long-tailed bear”) in the second edition of his Systema Naturae, then as Ursus Lotor (“washer bear”) in the tenth edition.[9] In 1780, Gottlieb Conrad Christian Storr placed the raccoon in its own genus Procyon, what can be translated to either mean “before the dog” or “doglike”.[10] It is also possible that Storr had its nocturnal lifestyle in mind and chose the star Procyon as eponym for the species.[11]

Evolution

According to fossils found in France and Germany, the first members of the family Procyonidae lived in Europe in the late Oligocene about 25 mya.[12] Similar teeth and skull structures suggest that procyonids and mustelids share a common ancestor, but molecular analysis speak for a closer relationship to bears.[13] After crossing the Bering Strait at least six million years later, the central distribution range of the then existing species was probably located in Central America.[14] Coatis (Nasua and Nasuella) and raccoons (Procyon) may have descended as distinct species from the species Paranasua between 5.2 and 6.0 mya.[15] Contrary to this assumption based on morphological comparisons of fossils, a genetical analysis done in 2006 yielded the result, that raccoons are more closely related to the ringtails.[16] Unlike other procyonids, including the crab-eating raccoon (Procyon cancrivorus), the ancestors of the common raccoon left tropic and subtropic areas and migrated further north about 2.5 mya, what has been confirmed by fossils found in the Great Plains and dating back to the middle of the Pliocene.[17]

Subspecies

After their discovery, the following five species of raccoon found only on small Central American and Caribbean islands were often regarded as distinct species: the small-toothed and light Cozumel raccoon, the square-skulled and larger Tres Marias raccoon, the very similar Bahamas and Guadeloupe raccoon and the extinct Barbados raccoon. However, after studies of their morphological and genetic traits in 1999, 2003 and 2005, all but the Cozumel raccoon (Procyon pygmaeus) were listed as subspecies of the common raccoon in the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005.[18][19][20][21] Apart from those island raccoons, most of the other 19 subspecies differ only slightly in coat color, size and other physical characteristics.[22] One exception are the very small individuals of the subspecies found at the south coast of Florida and the adjacent islands like the Ten Thousand Island raccoon (Procyon lotor marinus).[23]

Description

Physical characteristics

Along the body raccoons measure between 41 and 71 cm (16.1–28.0 in), not including their bushy tail which can measure between 19.2 and 40.5 cm (7.6–15.9 in), but is usually not much longer than 25 cm (9.8 in).[24] The shoulder height is between 22.8 and 30.4 cm (9.0–12.0 in).[25] The body weight of an adult raccoon varies strongly with habitat and can range from 1.8 to 13.6 kg (4.0–30.0 lb), but is usually between 3.9 and 9.0 kg (8.6–19.8 lb).[26] The smallest speciemen are found in Southern Florida, while those near the northern limits of the raccoon's range tend to be the largest.[27] Usually, males are 15 to 20% heavier than females.[28] At the beginning of winter, a raccoon can weigh twice as much as in spring due to its fat storage.[29] The heaviest recorded wild raccoon weighed 28.4 kg (62.6 lb), by far the largest size recorded for a procyonid.[30]

The most characteristic physical feature of the raccoon is the area of black fur around the eyes which sets itself apart from the surrounding white face coloring. This reminiscent of a “bandit's mask” has enhanced its reputation for mischief.[31] The slightly rounded ears are also bordered by white fur. It is assumed that the noticeable face coloring and the alternating light and dark rings on the tail help raccoons to quickly recognize the mimic and posture of conspecifics. The dark mask may also reduce glare and thus enhance night vision.[32] With the exception of the rare albinos, the coat on the other body parts consists of gray and brown hairs. Raccoons with a very dark coat are more common in the German population because individuals with such a coloring were among the ones being initially released to the wild.[33]

The raccoon, who is usually considered to be plantigrade, can sit on its hind legs to examine objects with its front paws.[34] With its short legs compared to the compact torso, a raccoon is not able to run fast or to jump far.[35] Raccoons can swim with an average speed of about 4.8 km/h (3.0 m/h) and stay in the water for several hours.[36] The dentition—40 teeth with the dental formula 3142/3142—is adapted to their omnivorous lifestyle: The carnassials are not as sharp and pointed as those of a carnivore, but the molars are also not as wide as those of a herbivore.[37] The penis bone of males is about 10 cm (3.9 in) long and strongly bent at the front end.[38] Seven of the 13 identified vocal calls are used in the communication between the mother and her kits, for example the birdlike twittering of newborn kits.[39]

Senses

The most important sense for the raccoon is its sense of touch.[40] The “hyper sensitive”[41] front paws with five freestanding fingers are surrounded by a thin layer of callus for protection. Almost two thirds of the area responsible for sensory perception in the cerebral cortex is specialised for the interpretation of tactile impulses, more than in any other animal.[42] With their vibrissae above their sharp, not retractable claws they are able to identify objects before touching them.[43] It is not known why it has no negative effects to its tactile perception when a raccoon stands in cold water below 10° C for hours.[44] However, the paws lack an opposable thumb and thus the agility of the hands of primates.[45]

The eyes of raccoons, which are thought to be color-blind but at least color-weak, work especially well for green light.[46] Although they see well in the twilight due to the tapetum lucidum behind the retina and the accommodation of 11 Dioptre is comparable to that of humans, the visual perception is of subordinate importance to raccoons because of their poor distance vision.[47] In addition to being useful for orientation in the dark, their olfaction is important for communicating with conspecifics.[48] Urine, feces, and gland secretions, usually distributed with their anal glands, are used for marking.[49] With their audition, they can perceive high tones up to 50–85 kHz and very low noices like those produced by earthworms underground.[50]

Intelligence

Very few studies, most built upon their sensory perception, have been done to determine the mental abilities of raccoons. In 1908, the ethologist H. B. Davis compared their learning speed with those of Rhesus Macaques after they had opened 11 of 13 complex locks in less than 10 tries.[51] Studies in 1963, 1973, 1975 and 1992 concentrated on their memory and have shown that raccoons remember the solution to once learned tasks up to three years later.[52] Stanislas Dehaene reports in his book The number sense that raccoons can distinguish boxes containing two or four grapes from those containing three.[53]

Behavior

Social behavior

Studies done in the 1990s by the ethologists Stanley D. Gehrt and Ulf Hohmann have indicated that raccoons show a gender-specific social behavior and are not typically loners as previously thought.[54][55] Related females often live in a so-called fusion-fission-society, that is, they share a common area and occasionally meet at feeding grounds or sleeping places.[56] Unrelated males often form loose male social groups to sustain their position against invaders and particularly against foreign males during the mating season.[57] Such a group does usually not consist of more than four individuals.[58] Since some males show aggressive behavior against unrelated kits, mothers will separate from conspecifics until their kits are big enough to defend themselves.[59] This social structure is called a three class society by Hohmann.[60] Zoologist Samuel I. Zeveloff is more cautious in his interpretation and outlines that at least the females live solitary most of the time and, according to Erik K. Fritzell's study in North Dakota in 1978, also males in areas with low population densities.[61] Concerning the behavior pattern of raccoons, Gehrt points out that “typically you'll find 10 to 15 percent that will do the opposite”.[62]

Shape and sizes of home ranges vary depending on gender and habitat, with adults claiming areas more than twice as large as juveniles.[63] While the size of home ranges in the ill-suited habitat of North Dakota's prairies lay between 6.7 and 49.5 km² for males and between 2.3 and 16.3 km² for females, the average size was 0,49 km² in a marsh at Lake Erie.[64] Irrespective of whether the home ranges of adjacent groups overlap or not, they are most likely not actively defended outside the mating season and if food supplies are sufficient. It has been observed that raccoons occasionally leave messages in the form of odor marks for information exchange about feeding grounds or sleeping places and meet there later for collective eating, sleeping and playing.[65]

Diet

Though usually nocturnal, raccoons are sometimes active at daylight to take advantage of available food sources.[66] Their diet consists of about 40% of invertebrates, 33% of plant foods and 27% of vertebrates.[67] According to Zeveloff, the raccoon “may well be one of the world's most omnivorous animals”.[68] While eating mostly insects, worms and other animals already available as food source in spring and early summer, raccoons prefer fruit and nuts rich in calories in late summer and autumn to build up a fat storage for winter.[69] Contrary to popular belief, raccoons eat birds and small mammals only occasionally, since the demanding hunt to catch them does not pay off.[70] Instead, fish and amphibians are their main prey animals regarding vertebrates.[71] When food is plentiful, raccoons can develop strong individual preferences for specific foods.[72] In the northern parts of their distribution range, raccoons reduce their activity in a winter rest drastically as long as a permanent snow cover makes searching for food impossible.[73]

Dousing

Raccoons sample food and other objects with their front paws to get a picture of it and to remove unwanted parts. In addition, it increases the tactile sensibility of their paws when the callus is softened underwater.[74] Captive raccoons sometimes carry their food to a watering hole to “wash”, or douse, it before eating it; a behavior not observed in the wild.[75] Naturalist Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon (1707–1788) believed that raccoons do not have adequate salivary glands to moisten food, which is definitely incorrect.[76] Captive raccoons douse their food more frequently, when a watering hole with a ground similar to a stream bottom is not further away than 3.0 m (10 ft).[77] The widely accepted theory that dousing is a vacuum activity to mimic foraging at shores for aquatic foods is supported by the observation that such foods are doused more frequently.[78] Cleaning dirty food does not seem to play a role for “washing”.[79] Observations that even wild raccoons may dunk very dry food are opposed by other experts.[80]

Reproduction

Raccoons usually mate between late January and mid-March in a period triggered by increasing daylight.[81] However, there are large regional differences not completely explainable by solar conditions: While raccoons in southern states typically mate later, the mating season in Manitoba also peaks in March and may occur as late as June.[82] If a female does not get pregnant or loses her kits early, she sometimes gets ready for conception again 80 to 140 days later.[83] During the mating period, the males restlessly roam their home ranges and court the females, whose three to four days long conception periods coincide, at central meeting places.[84] Copulation, including foreplay, can last over an hour and is repeated over several nights.[85] It is assumed that weaker members of a male social group also get the chance for mating, since stronger ones cannot mate with all available females.[86] In a study in southern Texas during the mating seasons from 1990 to 1992, about two thirds of all females mated with one male.[87]

After around 63 to 65 days of pregnancy (54–70 days possible), a litter of typically two to five young is born.[88] The average litter size varies strongly with habitat, ranging from 2.5 in Alabama to 4.8 in North Dakota.[89] Larger litter sizes are more common in areas with a high mortality rate, for example due to hunting or long and cold winters.[90] While male yearlings usually reach their sexual maturity after the main mating season, female yearlings can compensate high mortality rates as well and be responsible for about 50% of all young born in one year.[91] Males have no part in raising the young.[92] The kits are blind and deaf at birth, but their mask already stands out on their light fur.[93] The birth weight of the 9.5 cm (3.7 in) long kits is between 60 and 75 g (2.1–2.6 oz).[93] They open their eyes for the first time after around 21 days.[93] Weighing around 1 kg (2.2 lb), the kits leave the den and consume solid food for the first time after 6 to 9 weeks.[94] After that, their mother lactates them with decreasing intensity, usually not longer than 16 weeks in total.[95] In fall, after their mother has shown them dens and feeding grounds, the juveniles split up.[96] While many females stay close to the home range of their mother, males sometimes move away more than 20 km (12.4 mi).[97] This is considered to be an instinctive behavior to prevent incest.[98] However, mother and offspring may share one den during the first winter in cold areas.[99]

Life expectancy

Just as well as captive raccoons, wild ones can get 16 years old, but most live only a few years.[100] It is not unusual that only half of the young born in one year survive until their first birthday.[101] After that, the yearly mortality rate drops to 10 to 30%.[102] One of the main causes of death for young raccoons besides losing their mother is starvation during the next winter, especially if it is a cold and long one.[103] The most frequent natural cause of death in North America is the disease distemper which can get epidemic and kill most raccoons living in one area.[104] In areas with much traffic and extensive hunting, those two causes can account for up to 90% of all deaths of adult raccoons.[105] Getting killed by bobcats, coyotes and other predators usually does not play a significant role as cause of death, especially since bigger predators have been exterminated in many areas by humans.[106] In conclusion, the species' life expectancy in the wild is only about 1.8 to 3.1 years, depending on the local conditions in terms of traffic volume, hunting and extreme weather conditions.[107]

Range

Habitat

Although they have thrived in sparsely wooded areas in the last decades, raccoons depend on vertical structures to climb up when feeled threatened for saftey needs.[108] Therefore, they avoid open terrain and areas with many beech trees because they cannot climb up too smooth tree trunks.[109] If out of reach of their preferred main sleeping places, like tree hollows of old oaks or quarries, raccoons chose badger setts, the undergrowth or tree crotches for sleeping.[110] In a study in the German low mountain range Solling, more than 60% of all sleeping places were used only once, but those used at least 10 times accounted for about 70% of all overday stays.[111] Since amphibians, crustaceans and other animals found at the shore of lakes and rivers are an important part of their diet, humid deciduous or mixed forests sustain the highest population densities. While population densities lie between 0.5 and 3.2 animals per square kilometer in prairies and do usually not exceed six animals per square kilometer in upland hardwood forests, more than 20 raccoons can live per square kilometer in bottomland forests and marshes.[112]

Distribution in North America

Raccoons are common throughout North America from Canada to Panama, where the subspecies Procyon lotor pumilus coexists with the crab-eating raccoon.[113] The population on Hispaniola was exterminated by Spanish colonists, who hunted them for their meat, as early as 1513.[114] Raccoons were also exterminated on Cuba and Jamaica, where the last individuals were seen in 1687.[115] The three not yet extinct island raccoon subspecies (see the chapter about “Subspecies”) were classified as endangered by the IUCN in 1996.[116][117][118]

There are signs that raccoons were only numerous along rivers and in the woodlands of the Southeastern United States in pre-columbian times.[119] Their initial spread may have begun a couple of decades before the 20th century, since raccoons were not mentioned in earlier reports of pioneers exploring the central and north-central parts of the United States.[120] Since the 1950s, raccoons have expanded their range from Vancouver Island as northernmost locale far into the north of the four south-central Canadian provinces.[121] Entirely new habitats recently occupied by raccoons besides urban areas include mountain ranges like the Western Rocky Mountains, prairies and coastal marshes.[122] The estimated number of raccoons in North America in the late 1980s was 15 to 20 times higher than in the 1930s when raccoons were comparatively rare; a population explosion which started with their 1943 breeding season.[123] Urbanisation, the expansion of agriculture, deliberate introductions and the extermination of predators like wolves may have caused the increase in abundance and distribution.[124]

Distribution outside North America

All raccoons living outside North America are the offspring of animals which escaped from fur farms or were deliberately released to the wild. Today, stable populations exist in most parts of Germany as well as areas of the bordering countries. Other populations are located in the South of Belarus, the Caucasus region and in the North of France where several were released by American soldiers near Laon in 1966.[125]

Distribution in Germany

On April 12 1934, two pairs were released into the German wilderness at the Edersee in the north of Hesse by forest superintendent Wilhelm Freiherr Sittich von Berlepsch upon request of their owner, the poultry grower Rolf Haag.[126] He released them two weeks before getting permission from the Prussian hunting office to "enrich the fauna" by doing so.[127] Although there had been several prior attempts to introduce raccoons into the local environment, none had been successful.[128] A second population originated in East Germany in 1945 when 25 raccoons escaped from a fur farm at Wolfshagen to the east of Berlin after an air strike. The two populations are parasitologically distinguishable: 70% of the raccoons of the Hessian population are infected with the roundworm Baylisascaris procyonis, but none of the Brandenburgian population.[129] The estimated number of raccoons was 285 animals in 1956 and over 20,000 animals in 1970 in the Hessian region and between 200,000 and 400,000 animals in 2008 in the whole of Germany.[130][104]

The raccoon was a protected species in Germany until having been declared a game animal in 14 states since 1954.[131] Hunters and environmentalists argue that the raccoon spreads uncontrollably, having a devastating effect on protected birds and other species.[33] This view is opposed by zoologists Ulf Hohmann and Frank-Uwe Michler. Hohmann argues that the absence of natural predators does not justify extensive hunting since predation does also not play a significant role as death cause in North America.[132] Michler outlines that there are no signs that a high population density of raccoons has negative effects to the biodiversity of the area.[33] Both acknowlede that raccoons can decimate local bird populations, but denounce unscientific finger pointing at raccoons as “scapegoats”.[133][33]

Urban raccoons

Due to its adaptability, the raccoon has been able to use urban areas as a habitat. The first sightings occurred in a suburb of Cincinnati, Ohio, in the 1920s. Since the 1950s, raccoons have been present in metropolises like Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Toronto.[134] Since the 1960s, Kassel hosts Europe's first and densest population in a large urban area with about 50 to 150 animals per square kilometer (129–388 animals per square mile), a figure comparable to those in urban habitats in North America.[135][134] Home range sizes of urban raccoons drop to about 0.03 to 0.38 km² (0.01–0.15 mi²) for females and 0.08 to 0.79 km² (0.03–0.31 mi²) for males.[136] In small towns and suburbs, many raccoons sleep in a nearby forest after foraging in the settlement area.[137][134] Fruit and insects in gardens and leftovers in the garbage are easily available food sources.[138] There also exists a large number of additional sleeping places like tree hollows in old garden trees, cottages, garages, abandoned houses and attics. The number of raccoons sleeping in houses varies, ranging from 15% in Washington, D.C. (1991) to 43% in Kassel (2003).[139]

Diseases

Raccoons can carry raccoon rabies, a lethal disease caused by the neurotropic rabies virus carried in the salvia and transmitted by bites.[140] Its spread has begun in Florida and Georgia in the 1950s and was facilitated by the intoduction of infected individuals to Virginia and North Dakota in the late 1970s.[141] Of the 6,940 documented rabies cases reported in the United States in 2006, 2,615 (37.7%) were in raccoons.[142] The U.S. Department of Agriculture, as well as local authorities in several U.S. states and Canadian provinces, have developed oral vaccination programs to fight the spread of the disease in endangered populations.[143][144][145] Although raccoon rabies is as dangerous to humans as any other strain, only one fatal case has been reported.[146] Among the main indicators for rabies in raccoons are sick appearance, impaired mobility, abnormal vocalization and aggressiveness.[147] However, there may also be no visible signs and most individuals do not show the aggressive behavior known from canids and retire to their den instead.[147][33][148] It is recommended to not approach conspicuous looking or acting animals and to notify proper authorities like an animal control officer from the local health department.[149][150] Seeing a raccoon at daylight is thought to be an indicator of rabies, but healthy animals, especially nursing mothers, occasionally also forage in the daytime.

Unlike rabies and at least one dozen other pathogens carried by raccoons, distemper does not affect humans.[151] This epizootic virus disease is the most frequent natural cause of death in North America and affects raccoons of all age groups, for example 94 of 145 raccoons died during one outbreak in Clifton, Ohio, in 1968.[104][152] It may occur conjoined with a following infection with the encephalitis virus, causing together the same symptoms like rabies.[153] In Germany, the first eight cases of distemper were reported in 2007.[104] Some of the most important bacterial diseases are leptospirosis, listeriosis, tetanus and tularemia. Although internal parasites weaken their immune system, well-fed individuals can carry a great many roundworms in their alimentary system without showing symptoms.[154] When cleaning latrines, a breathing protection should be worn to not ingest larvae of the Baylisascaris procyonis roundworm, which seldom causes a severe illness in humans.[155]

Raccoons and people

Conflicts

The increasing number of raccoons in urban areas has resulted in extremely diverse reactions ranging from absolute rejection to intensive feeding.[156] Some wildlife experts and most public authorities caution against feeding wild animals, because they might get increasingly obtrusive and dependant on humans as food source.[157] Other experts challenge such arguments and give advice for feeding wildlife in their books.[158][159] Showing no fear of humans is most likely not an indicator for rabies, but a behavior adjustment after living in the city for many generations.[160] Raccoons usually do not prey on domestic cats and dogs, but individual cases of killings have been reported.[161]

While overthrown trash cans and raided fruit trees are merely regarded as a nuisance by house owners, it can cost thousands of dollars to repair damages caused by the use of attics as dens.[162] Relocating or killing raccoons without permit is forbidden in many urban areas for animal welfare causes and usually only solves problems with particularly wild or even aggressive individuals, since adequate dens are either known to several raccoons or will be rediscovered soon.[163][150] Loud noise or unpleasant smell, like that from coyote urine, may drive away single animals, but precautionary meassures to restrict access to garbage and denning sites are more effective and cheaper.[164][150] When a mother uses the chimney or attic as nesting place it is the easiest to wait until she and her kits will leave when they are about eight weeks old.[150] Since raccoons are able to increase their reproduction rate up to a certain limit, extensive hunting does often not solve problems with raccoon populations (see the chapter about “Reproduction”). Older males also claim larger home ranges than younger ones, resulting in a lower population density.[33] The costs of large-scale measures to drive out all raccoons from one area temporarily are usually many times higher than the costs of the damages done by the raccoons.[33]

In mythology and culture

In the mythology of the indigenous peoples of the Americas the raccoon was the subject of folk tales.[165] Stories like How raccoons catch so many crayfish from the Tuscarora centered on its skills at foraging.[166] In other tales, the raccoon played the role of the trickster who outsmarts other animals like coyotes and wolves.[167] Among others, the Dakota Sioux believed that the raccoon has spirit powers due to its mask which resembled the facial paintings used during rituals.[168] The Aztecs linked supernatural abilities especially to females.[169]

In Western culture, several autobiographical novels about living with a raccoon exist, mostly written for children. The most well known is Sterling North's Rascal in which he tells how he raised a kit during the time of the First World War. In the last years, anthropomorphic raccoons played a main role in the animated television series The Raccoons, the computer-animated film Over the Hedge and the video game series Sly Cooper. (→ List of fictional raccoons)

Hunting and fur trade

The fur of raccoons is used for fur clothing, especially for coats and the characteristic coonskin caps. Native American tribes did not only make winter clothing of it, but also used the tails as accessoires.[170] In the 19th century, when coonskins even served as means of payment, several thousand raccoons were killed each year in the United States.[171] This number rose quickly when automobile coats got popular after the turn of the century. In the 1920s, wearing a raccoon coat was regarded as status symbol among college students.[172] Attempts to breed raccoons in fur farms in the 1920s and 1930s in North America and Europe were not profitable and given up after the prices for long-haired pelts dropped in the 1940s.[173][174] Although raccoons had gotten rare in the 1930s, at least 388,000 were killed during the hunting season 1934/35.[175]

After the sustained population increase starting with the breeding season in 1943, the bag reached about one million animals in 1946/47 and two million in 1962/63.[176] The broadcast of three television episodes about the frontiersman Davy Crockett and the film Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier compiling them in 1954 and 1955 led to a high demand of coonskin caps the United States.[177] Ironically, most likely neither Crockett nor the actor wore a cap made out of raccoon fur.[178] The bag reached an all-time high with 5.2 million animals in 1976/77 and ranged between 3.2 and 4.7 million for most of the 1980s, before falling to 0.9–1.9 million in the first half of the 1990s due to low pelt prices.[179]

As food

While being primarily hunted for their fur, raccoons were also a source of food for many Native Americans, as well as for early American pioneers.[180] Today, several thousand raccoons are eaten each year in the United States.[181] Its culinary use is mainly identified with certain regions of the American South like Arkansas where the Gillett Coon Supper is an important political event.[182] The first edition of The Joy of Cooking, released in 1931, had a recipe for preparing raccoon. It is suggested that removing the scent glands and fat before roasting will help tone down the strong game flavor.[183]

As pets

Raccoons are sometimes kept as pets, though this is discouraged by many experts because the raccoon is not a domesticated species and may act unpredictably and aggressively.[184][185] When keeping raccoons as pets is not forbidden like in Wisconsin and other U.S. states, an exotic pet permit can be required.[186][187] It is also possible for a pet raccoon to be taken out by local authorities for a rabies test after biting another person. However, raccoons acquired from a reputable breeder can make suitable pets if kept according to their needs by a responsible owner.[188]

Sexual mature raccoons often show aggressive natural behaviors like biting during mating season.[189] Neutering them at around five or six months of age decreases the chance of this happening.[190] Raccoons can develop obesity and other disorders due to unnatural diet and lack of exercise.[191] When fed with cat food over a long time period, like often done, raccoons can get gout.[192] With regard to the result of the latest research about their social behavior, veterinarian Bernhard Böer argues that raccoons should not be kept alone because they may grow lonely without contact to conspecifics.[193] Since they will most likely wreak havoc in the household due to their inborn curiosity, raccoons are usually kept in a pen, which is required by law in Germany.[194] It is usually impossible to teach raccoons to obey commands.[195]

Young orphan raccoons born in the wild are usually not kept as pets, but cared for and reintroduced into the wild through professional wildlife rehabilitation. It is often uncertain if a raccoon raised in captivity adapts well to a life in the wild.[196] Feeding kits, which are still in the need for a liquid food source, with cow milk instead of kitten replacement milk or similar products can be dangerous for their health.[197]

Notes

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 42

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 1

- ^ Larivière, Serge (2004). "Range expansion of raccoons in the Canadian prairies: review of hypotheses". Wildlife Society Bulletin. 32 (3). Lawrence, Kansas: Allen Press: 955–963. ISSN 0091-7648.

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 2

- ^ Holmgren, p. 23

- ^ Holmgren, p. 52

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 75–76; Zeveloff, p. 2

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 42–67

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 64, 67; Zeveloff, p. 5

- ^ Holmgren, p. 68; Zeveloff, p. 6

- ^ Hohmann, p. 44; Holmgren, p. 68

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 19

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 16, 18, 26

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 20, 23

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 24

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter (2007). "Phylogeny of the Procyonidae (Mammalia: Carnivora): Molecules, morphology and the Great American Interchange" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 43 (3). Amsterdam: Elsevier: 1076–1095. ISSN 1055-7903. Retrieved 2008-08-10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hohmann, p. 46; Zeveloff, p. 24

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 42–46

- ^ Helgen, Kristofer M. (2003). "Taxonomic status and conservation relevance of the raccoons (Procyon spp.) of the West Indies". Journal of Zoology. 259 (1). Oxford: The Zoological Society of London: 69–76. ISSN 0952-8369.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Helgen, Kristofer M. (2005). "A Systematic and Zoogeographic Overview of the Raccoons of Mexico and Central America". In Sánchez-Cordero, Víctor; Medellín, Rodrigo A. (ed.). Contribuciones mastozoológicas en homenaje a Bernardo Villa. Mexico City: Instituto de Ecología of the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. p. 230. ISBN 978-9703226030. Retrieved 2008-08-09.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - ^ Wozencraft, W. C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 627–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ MacClintock, p. 9; Zeveloff, pp. 79–89

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 82–83

- ^ Hohmann, p. 77; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 15; Zeveloff, p. 58

- ^ Lagoni-Hansen, p. 16

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 58–59

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 59

- ^ Lagoni-Hansen, p. 18

- ^ MacClintock, p. 44; Zeveloff, p. 108

- ^ MacClintock, p. 8; Zeveloff, p. 59

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 61

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 65–66; MacClintock, pp. 5–6; Zeveloff, p. 63

- ^ a b c d e f g Michler, Frank-Uwe (2008). "Ökologische und ökonomische Bedeutung des Waschbären in Mitteleuropa – Eine Stellungnahme". „Projekt Waschbär“ (in German). Retrieved 2008-06-26.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Zeveloff, p. 71–72

- ^ Hohmann, p. 93; Zeveloff, p. 72

- ^ MacClintock, p. 33; Zeveloff, p. 72

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 64

- ^ MacClintock, p. 84

- ^ Hohmann, p. 66; MacClintock, p. 92; Zeveloff, p. 73

- ^ Hohmann, p. 55; Zeveloff, p. 70

- ^ Hohmann, p. 55

- ^ Hohmann, p. 56

- ^ Hohmann, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 70

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 60, 62

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 70

- ^ Hohmann, p. 63; MacClintock, p. 18; Zeveloff, p. 66

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 63, 65; MacClintock, pp. 18–21; Zeveloff, pp. 66–67

- ^ Hohmann, p. 67

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 68–70; MacClintock, p. 17; Zeveloff, pp. 68–69

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 66, 72; Zeveloff, p. 68

- ^ Davis, H. B. (1907). "The Raccoon: A Study in Animal Intelligence". The American Journal of Psychology. 18 (4). Champaign, Illinois: University of Illinois Press: 447–489.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hohmann, pp. 71–72

- ^ Dehaene, Stanislas (1997). The number sense. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 12. ISBN 0-19-511004-8.

- ^ Stanley D. Gehrt: Raccoon social organization in South Texas. 1994 (dissertation at the University of Missouri)

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 133–155

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 141–142

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 152–154

- ^ Hohmann, p. 140

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 124–126, 155

- ^ Hohmann, p. 133

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 137–139

- ^ Riddell, Jill (2002). "The City Raccoon and the Country Raccoon". Chicago Wilderness Magazine. Chicago Wilderness Magazine. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ^ MacClintock, p. 61

- ^ MacClintock, pp. 60–61

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 142–147

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 99

- ^ Hohmann, p. 82

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 102

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 85–86, 88; MacClintock, pp. 44–45

- ^ Hohmann, p. 83

- ^ Hohmann, p. 83

- ^ MacClintock, p. 44

- ^ MacClintock, pp. 108–113

- ^ Hohmann, p. 55; Zeveloff, p. 7

- ^ Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, pp. 56–57

- ^ Holmgren, p. 70; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41; MacClintock, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 7

- ^ MacClintock, p. 57

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 44–45; Lagoni-Hansen, pp. 41–42; MacClintock, p. 57; Zeveloff, p. 7

- ^ MacClintock, p. 57

- ^ Holmgren, p. 22 (pro); Lagoni-Hansen, p. 41 (contra)

- ^ Hohmann, p. 150; MacClintock, p. 81; Zeveloff, p. 122

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 122

- ^ Hohmann, p. 124; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 45; Zeveloff, p. 125

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 148–150; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 47; MacClintock, pp. 81–82

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 150–151

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 153–154

- ^ Gehrt, Stanley (1999). "Behavioural aspects of the raccoon mating system: determinants of consortship success". Animal behaviour. 57 (3). Amsterdam: Elsevier: 593–601. ISSN 0003-3472.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hohmann, p. 131; Zeveloff, pp. 121, 126

- ^ Lagoni-Hansen, p. 50; Zeveloff, p. 126

- ^ Bartussek, p. 32; Zeveloff, p. 126

- ^ Hohmann, p. 163; MacClintock, p. 82; Zeveloff, pp. 123–127

- ^ MacClintock, p. 83

- ^ a b c Zeveloff, p. 127

- ^ Hohmann, p. 119; MacClintock, pp. 94–95

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 129

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 126–127. Zeveloff, p. 130

- ^ Hohmann, p. 130; Zeveloff, pp. 132–133

- ^ Hohmann, p. 128; Zeveloff, p. 133

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 130

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 119

- ^ Hohmann, p. 163; Zeveloff, p. 119

- ^ Hohmann, p. 163

- ^ MacClintock, p. 73

- ^ a b c d Michler, Frank-Uwe (2008). "Erste Ergebnisse". „Projekt Waschbär“ (in German). Retrieved 2008-06-24.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Hohmann, p. 162

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 111–112

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 118–119

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 93–94; Zeveloff, p. 93

- ^ Hohmann, p. 94

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 97–100; Zeveloff, pp. 95–96

- ^ Hohmann, p. 98

- ^ Hohmann, p. 160; Zeveloff, p. 97

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 12, 46; Zeveloff, pp. 75, 88

- ^ Holmgren, p. 58

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 58–59

- ^ Template:IUCN2007

- ^ Template:IUCN2007

- ^ Template:IUCN2007

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 77

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 78

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 75

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 76

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 75–76

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 76–78

- ^ Lagoni-Hansen, pp. 90–91

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 9–10

- ^ Hohmann, p. 10

- ^ Hohmann, p. 11; Lagoni-Hansen, p. 84

- ^ Hohmann, p. 182

- ^ Hohmann, p. 11

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 18, 21

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 13–14

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 18–19

- ^ a b c Michler, Frank-Uwe (2003-06-25). "Untersuchungen zur Raumnutzung des Waschbären (Procyon lotor, L. 1758) im urbanen Lebensraum am Beispiel der Stadt Kassel (Nordhessen)" (PDF): 7. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hohmann, p. 108

- ^ Michler, Frank-Uwe. "Stand der Wissenschaft". „Projekt Waschbär“ (in German). Gesellschaft für Wildökologie und Naturschutz e.V. Retrieved 2008-07-01.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bartussek, p. 20

- ^ Bartussek, p. 21

- ^ Bartussek, p. 20; Hohmann, p. 108

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 113

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 113

- ^ Blanton, Jesse D. (2007-08-15). "Rabies surveillance in the United States during 2006". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 231 (4). Schaumburg, Illinois: American Veterinary Medical Association: 540–556. ISSN 0003-1488.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "National Rabies Management Program Overview". Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. United States Department of Agriculture. 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ "Raccoons and Rabies". Tennessee.gov – The Official Web Site of the State of Tennessee. Tennessee Department of Health. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ "Quebec uses bait to vaccinate raccoons to keep rabies out of Montreal". The Chronicle. Media Transcontinental. 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- ^ Silverstein, M. A. (2003-11-14). "First Human Death Associated with Raccoon Rabies". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 52 (45). Atlanta, Georgia: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 1102–1103. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Rosatte, Rick (2006). "Behavior, Movements, and Demographics of Rabid Raccoons in Ontario, Canada: Management Implications". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 42 (3). USA: The Wildlife Disease Association: 589–605. ISSN 0090-3558. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Hohmann, p. 182

- ^ "The Raccoon—Friend or Foe?". Northeastern Area State & Private Forestry - USDA Forest Service. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ^ a b c d Link, Russell. "Raccoons". Living with Wildlife. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

- ^ MacClintock, p. 72; Zeveloff, p. 114

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 112

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 113

- ^ MacClintock, pp. 73–74; Zeveloff, p. 114

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 169, 182

- ^ Hohmann, pp. 103–106

- ^ Bartussek, p. 34

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 117–121

- ^ Harris, Stephen (2001). Urban Foxes. Suffolk: Whittet Books. pp. 78–79. ISBN 978-1873580516.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Bartussek, p. 24; Hohmann, p. 182

- ^ "Raccoons rampaging Olympia". seattlepi.com. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. 2006-08-23. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Michler, Frank-Uwe (2003-06-25). "Untersuchungen zur Raumnutzung des Waschbären (Procyon lotor, L. 1758) im urbanen Lebensraum am Beispiel der Stadt Kassel (Nordhessen)" (PDF): 108. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Bartussek, p. 32; Hohmann, pp. 142–144, 169

- ^ Bartussek, pp. 36–40; Hohmann, p. 169

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 25–46

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 41–43

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 26–29, 38–40

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 15–17

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 17–18

- ^ Holmgren, p. 18

- ^ Holmgren, p. 74; Zeveloff, p. 160

- ^ Holmgren, p. 77

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 161

- ^ Schmidt, Fritz (1970). Das Buch von den Pelztieren und Pelzen (in German). Munich: F. C. Mayer Verlag. pp. 311–315.

- ^ Holmgren, p. 77; Zeveloff, pp. 75, 160, 173

- ^ Zeveloff, pp. 75, 160

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 170

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 170

- ^ Zeveloff, p. 160–161

- ^ Holmgren, pp. 18–19, Zeveloff, p. 165

- ^ "Raccoon". Nebraska Wildife Species Guide. Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ^ Berry, Marion. "Gillett Coon Supper". Local Legacies: Celebrating Community Roots. The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "Wild Game Recipes - Raccoon Information". Martin County Center. NC State University. 2006-02-17. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Bartussek, p. 44

- ^ "Pet Raccoons?". Raccoon Tracks. 2005. Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ^ MacClintock, p. 129

- ^ Bluett, Robert (1999). "The Raccoon (Procyon lotor)" (PDF). Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System: 2. Retrieved 2008-07-31.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ MacClintock, p. 130

- ^ Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 185–186

- ^ Hohmann, p. 186

- ^ Hohmann, p. 185

- ^ Hohmann, p. 180

- ^ Hohmann, p. 184

- ^ Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 184, 187; MacClintock, p. 130–131

- ^ Bartussek, p. 44

- ^ MacClintock, p. 130

- ^ Bartussek, p. 44; Hohmann, pp. 175–176

References

- Bartussek, Ingo (2004). Die Waschbären kommen (in German). Niedenstein, Germany: Cognitio. ISBN 978-3932583100.

- Hohmann, Ulf (2001). Der Waschbär (in German). Reutlingen, Germany: Oertel+Spörer. ISBN 978-3886273010.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - Holmgren, Virginia C. (1990). Raccoons in Folklore, History and Today's Backyards. Santa Barbara, California: Capra Press. ISBN 978-0884963127.

- Lagoni-Hansen, Anke (1981). Der Waschbär (in German). Mainz, Germany: Verlag Dieter Hoffmann. ISBN 3-87341-037-0.

- MacClintock, Dorcas (1981). A Natural History of Raccoons. Caldwell (New Jersey): The Blackburn Press. ISBN 978-1930665675.

- Zeveloff, Samuel I. (2002). Raccoons: A Natural History. Washington, D. C.: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1588340337.

External links

- Living with Wildlife: Raccoons: information about dealing with urban raccoons from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife

- Raccoon Tracks: general information about raccoons

- Remo Raccoon's Home Page: website about pet raccoons, including information about First Aid help and U.S. state regulations (October 2000)