Portuguese Brazilians: Difference between revisions

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

Some of the earliest colonists for whom we have written records are [[João Ramalho]] and [[Caramuru]]. At the time the Portuguese Crown was focused on securing its highly lucrative [[Portuguese Empire]] in Asia, and so did little to protect the newly discovered lands in the Americas from foreign interlopers. As a result, many pirates, mainly [[French people|French]], began dealing in [[pau brasil]] with the Amerindians. This situation worried Portugal, which in the 1530s started to colonize Brazil, principally for defensive reasons. The towns of [[Cananéia]] (1531), [[São Vicente, São Paulo|São Vicente]] (1532) and [[Iguape]] (1538) date from that period. |

Some of the earliest colonists for whom we have written records are [[João Ramalho]] and [[Caramuru]]. At the time the Portuguese Crown was focused on securing its highly lucrative [[Portuguese Empire]] in Asia, and so did little to protect the newly discovered lands in the Americas from foreign interlopers. As a result, many pirates, mainly [[French people|French]], began dealing in [[pau brasil]] with the Amerindians. This situation worried Portugal, which in the 1530s started to colonize Brazil, principally for defensive reasons. The towns of [[Cananéia]] (1531), [[São Vicente, São Paulo|São Vicente]] (1532) and [[Iguape]] (1538) date from that period. |

||

By the mid-16th century, Portuguese colonists were already settling in significant numbers, mainly along the coastal regions of Brazil. Numerous cities were established, including [[Salvador, Bahia|Salvador]] (1549), [[São Paulo]] (1554) and [[Rio de Janeiro]] (1565). While there were Portuguese settlers who came willingly, some were forced exiles or ''degredados''. Such convicts were sentenced for a variety of crimes according to the ''Ordenações do Reino'', which included common theft, attempted murder |

By the mid-16th century, Portuguese colonists were already settling in significant numbers, mainly along the coastal regions of Brazil. Numerous cities were established, including [[Salvador, Bahia|Salvador]] (1549), [[São Paulo]] (1554) and [[Rio de Janeiro]] (1565). While there were Portuguese settlers who came willingly, some were forced exiles or ''degredados''. Such convicts were sentenced for a variety of crimes according to the ''Ordenações do Reino'', which included common theft, attempted murder and adultery. <ref>{{cite web|title=A pena do degredo nas Ordenações do Reino|url=http://jus2.uol.com.br/doutrina/texto.asp?id=2125&p=1|accessdate=2010-08-18}}</ref> |

||

During the 17th century, most Portuguese settlers in Brazil, who throughout the entire colonial period tended to originate from Northern Portugal <ref>{{cite web|title=ENSAIO SOBRE A IMIGRAÇÃO PORTUGUESA E OS PADRÕES DE MISCIGENAÇÃO NO BRASIL|url=http://www.ppghis.ifcs.ufrj.br/media/manolo_imigracao_lusa.pdf|accessdate=2010-08-18}}</ref>, moved to the northeastern part of the country to establish the first [[sugar]] plantations. Some of the new arrivals were [[New Christians]], that is, descendents of Portuguese Jews who had been induced to convert to Catholicism and remained in Portugal, yet were often targetted by the Inquisition (established in 1536) under the accusation of being [[crypto-Jews]]. <ref>{{cite web|title=The Virtual Jewish History Tour - Brazil|url=http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Brazil.html|accessdate=2010-08-16}}</ref> |

During the 17th century, most Portuguese settlers in Brazil, who throughout the entire colonial period tended to originate from Northern Portugal <ref>{{cite web|title=ENSAIO SOBRE A IMIGRAÇÃO PORTUGUESA E OS PADRÕES DE MISCIGENAÇÃO NO BRASIL|url=http://www.ppghis.ifcs.ufrj.br/media/manolo_imigracao_lusa.pdf|accessdate=2010-08-18}}</ref>, moved to the northeastern part of the country to establish the first [[sugar]] plantations. Some of the new arrivals were [[New Christians]], that is, descendents of Portuguese Jews who had been induced to convert to Catholicism and remained in Portugal, yet were often targetted by the Inquisition (established in 1536) under the accusation of being [[crypto-Jews]]. <ref>{{cite web|title=The Virtual Jewish History Tour - Brazil|url=http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/vjw/Brazil.html|accessdate=2010-08-16}}</ref> |

||

===Growing Portuguese immigrants (1700-1822)=== |

===Growing Portuguese immigrants (1700-1822)=== |

||

Revision as of 15:19, 20 August 2010

Machado de Assis[1] · Daniela Mercury[2]

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| All Brazil | |

| Languages | |

| Portuguese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Brazilian people, Pardo, Afro-Brazilian Portuguese people |

Portuguese Brazilians (or Luso-Brazilians) are citizens of Brazil whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Portugal. As with most immigrant groups, the Portuguese sought economic prosperity. Although present since the onset of colonization, they began migrating in larger numbers without state support in the 19th century.

History

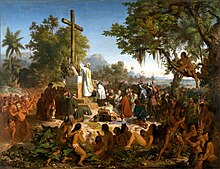

Early Settlement and Colonization (1500-1700)

Some of the earliest colonists for whom we have written records are João Ramalho and Caramuru. At the time the Portuguese Crown was focused on securing its highly lucrative Portuguese Empire in Asia, and so did little to protect the newly discovered lands in the Americas from foreign interlopers. As a result, many pirates, mainly French, began dealing in pau brasil with the Amerindians. This situation worried Portugal, which in the 1530s started to colonize Brazil, principally for defensive reasons. The towns of Cananéia (1531), São Vicente (1532) and Iguape (1538) date from that period.

By the mid-16th century, Portuguese colonists were already settling in significant numbers, mainly along the coastal regions of Brazil. Numerous cities were established, including Salvador (1549), São Paulo (1554) and Rio de Janeiro (1565). While there were Portuguese settlers who came willingly, some were forced exiles or degredados. Such convicts were sentenced for a variety of crimes according to the Ordenações do Reino, which included common theft, attempted murder and adultery. [5]

During the 17th century, most Portuguese settlers in Brazil, who throughout the entire colonial period tended to originate from Northern Portugal [6], moved to the northeastern part of the country to establish the first sugar plantations. Some of the new arrivals were New Christians, that is, descendents of Portuguese Jews who had been induced to convert to Catholicism and remained in Portugal, yet were often targetted by the Inquisition (established in 1536) under the accusation of being crypto-Jews. [7]

Growing Portuguese immigrants (1700-1822)

In the 18th century, immigration to Brazil from Portugal increased dramatically.[8] Many gold and diamond mines were discovered in the region of Minas Gerais, which then led to the arrival of not only Portuguese, but also of native-born Brazilians. Regarding the former, most were peasants from the Minho region in Portugal.[9] In the beginning, Portugal stimulated the immigration of minhotos to Brazil. After some time, however, the number of departures was so great that the Portuguese Crown had to establish barriers to further immigration. Most of these Portuguese involved in the goldrush ended up settling in Minas Gerais and in the Center-West region of Brazil, where they founded dozens of cities such as Ouro Preto, Congonhas, Mariana, São João del Rei, Tiradentes, Goiás, etc.

Between 1748 and 1756, 7,817 settlers from the Azores Islands arrived in Santa Catarina, located in the Southern Region of Brazil.[10] Several hundred couples of Azoreans also settled in Rio Grande do Sul.[11] The majority of those colonists, composed of small farmers and fishermen, settled along the litoral of those two states and founded the cities of Florianópolis and Porto Alegre. Unlike previous trends, in the south entire Portuguese families came to seek a better life for themselves, not just men. During this period, the number of Portuguese women in Brazil increased, which resulted in a larger white population. This was especially true in Southern Brazil.

A significant immigration of very rich Portuguese to Brazil occurred in 1808, when Queen Maria I of Portugal and her son and regent, the future João VI of Portugal, fleeing from Napoleon, relocated to Brazil with 15,000 members of the royal family, nobles and government and established themselves in Rio de Janeiro. They returned to Portugal in 1821, and in 1822 Brazil became independent. Thousands of ordinary Portuguese settlers left for Brazil after independence.

Portuguese immigration to Brazil (1822-present)

A few years after independence from Portugal in 1822, Portuguese people would start arriving in Brazil as immigrants, and the Portuguese population in Brazil actually increased. Most of them were peasants from the rural areas of Portugal. The majority settled in urban centers, mainly in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, working mainly as small traders or shopkeepers.

They and their descendants were quick to organize themselves and establish mutual aid societies (such as the Casas de Portugal), hospitals (e.g. Beneficência Portuguesa de São Paulo, Beneficência Portuguesa de Porto Alegre, Hospital Português de Salvador, Real Hospital Português do Recife, etc.), libraries (e.g. Real Gabinete Português de Leitura in Rio de Janeiro and in Salvador), newspapers (e.g. Jornal Mundo Lusíada), magazines (e.g. Revista Atlântico) and even sports clubs with football teams, including a major one, the Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama and several others such as Associação Atlética Portuguesa in Rio de Janeiro, the Associação Portuguesa de Desportos in São Paulo, the Associação Atlética Portuguesa Santista in Santos, the Associação Portuguesa Londrinense in Londrina, and the Tuna Luso Brasileira in Belém.

Dwindling Portuguese immigration (1960-present)

In the 1930s, the Brazilian President Getúlio Vargas established legislation that hindered the settlement of immigrants in Brazil. WWII reduced immigration from Europe to Brazil; after it, immigration grew again, but, with the completion of demographic transition in Europe, European emigration gradually dwindled. As this process in Portugal came later than elsewhere in Europe, Portuguese emigration diminished slowly; but it was also gradually redirected to North America and other European countries, particularly France.

However, between 1945 and 1963, during Salazar's dictatorship (Estado Novo), thousands of Portuguese citizens still immigrated to Brazil. Due to the independence of Portuguese overseas provinces after the Carnation Revolution in 1974, a new wave of Portuguese immigrants arrived in Brazil until the late 1970s as refugees[12][failed verification].

Economic reasons, with others of social, religious and political nature, are the main cause for the large Portuguese diaspora in Brazil. The country received the majority of Portuguese immigrants in the world.[13]

After Portugal's recovery from the effects of Salazarist dictatorship and colonial war, and in the 1980s and 1990s with the growth of the Portuguese economy and a deeper European integration, very few Portuguese immigrants came to Brazil.[14] In the 1990s and 2000s, Portuguese emigrants mainly went to the European Union, followed by Canada, the U.S.A., Venezuela and South Africa.

Portuguese immigration in numbers

| Portuguese immigration to Brazil Source: Brazilian Institute for Geography and Statistics[15] |

|||||||||||||||

| 1808-1817 | 1827-1829 | 1837-1841 | 1856-1857 | 1881-1900 | 1901-1930 | 1931-1950 | 1951-1960 | 1961-1967 | 1981-1991 | ||||||

| 24,000 | 2,004 | 629 | 16,108 | 316,204 | 754,147 | 148,699 | 235,635 | 54,767 | 4,605 | ||||||

Characteristics of the immigrants

The typical Portuguese immigrant in Brazil was a single man. As an example, in the records of the community of Inhaúma, in the countryside of the state of Rio de Janeiro, from 1807 to 1841, the Portuguese-born population comprised approximately 15% of the population, of whom 90% were males. Inhaúma was not unique: this trend had lasted since the beginning of colonization. In 1872, the Consul general of Rio de Janeiro reported: (...)49,610 (Portuguese) arrivals in the past ten years by sailing ships, major, male, 35,740 and, female, 4,280; of these, 13,240 married and 22,500 unmarried; minor, 9,590, as a family, 920(...)

Although these data are not complete — they do not include who arrived as passengers of small ships[citation needed] or illegally — we clearly see that females made up only 1/8 of total Portuguese immigration. In Bahia, as of 1872, the situation was even clearer: of a total of 1,498 Portuguese, only 64 were women (about 4.2%)[citation needed].

The disparity between the number of men and women among the Portuguese immigrants in Brazil really started to change in the early 20th century, when the largest numbers of Portuguese immigrated to Brazil.[16] In the records of the Port of Santos, between 1908 and 1936, Portuguese female immigrants accounted for 32.1% of the Portuguese who entered Brazil, compared to less than 10% before 1872. This figure was similar to the entries of women of other nationalities, such as Italians (35.3% of women), Spaniards (40.6%) and Japanese (43.8%) and higher than the figures found among "Turks" (actually Arabs, 26.7%) and Austrians (27.3%).[17] However, the majority still immigrated alone to Brazil (53%). Only the "Turks" (62.5%) arrived as unaccompanied immigrants in a higher percentage than the Portuguese. In comparison, only 5.1% of the Japanese immigrants arrived alone to Brazil. The Japanese kept a strong familiar connection when they immigrated to Brazil, with the largest numbers of family members, comprising 5.3 people, followed by Spaniards, with similar figures. The families of Italian origin included lower number of members, at 4.1. The Portuguese, among all immigrants, had the smallest number of people when they immigrated as families: 3.6. About 23% of the Portuguese who disembarked at the Port of Santos were under 12 years old. This figure shows that, for the first time in Brazil's history, large numbers of Portuguese families were settling in Brazil.[17]

The Portuguese also had one of highest illiteracy rates among immigrants arriving to Brazil during the early 20th century: 57.5% of them were illiterate. Only the Spaniards had a higher percentage of illiteracy: 72%. (In comparison, only 13.2% of the German immigrants to Brazil were illiterate.)[17]

Intermarriage with other ethnic groups

| Marriages of Portuguese immigrants in Rio de Janeiro (1907–1916) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nationalities of the grooms and brides | Number of marriages | ||

| Portuguese man and Portuguese woman | 6,964 | ||

| Portuguese man and Brazilian woman | 6,176 | ||

| Portuguese man and Spanish woman | 357 | ||

| Portuguese man and Italian woman | 156 | ||

| Portuguese man and another foreign woman | 100 | ||

| Total of marriages | 13,753 | ||

Records of the Portuguese immigrants to Brazil in the early 20th century reveal that they had the lowest levels of intermarriage with Brazilians among all European immigrants. Male Portuguese immigrants mainly married Portuguese female immigrants. Of the 22,030 Portuguese men and women who married in Rio de Janeiro from 1907 to 1916, 51% of men married Portuguese women. (Meanwhile 50% of the Italian men married Italian women and only 47% of Spanish men married women from their country.) Endogamy was even higher among the female Portuguese immigrants: 84% of Portuguese women in Rio married Portuguese men, compared to 64% of Italian and 52% of Spanish women who married men from their own countries. The high level of endogamy found among the more recent Portuguese immigrants in Brazil is surprising because of many reasons. In the early 20th century, most of the Portuguese immigrants in Rio were men (a ratio of 320 men to 100 women, compared to the proportion of 266 men to 100 women among all European immigrants). The Portuguese men had fewer female compatriots with whom they could marry than the other foreign men. Despite this, more Portuguese men married compatriots than the other immigrants. Despite the cultural and linguistic similarity between Brazilians and Portuguese, the high rates of endogamy of Portuguese immigrants may be attributed to the prejudice that Brazilians had toward Portuguese immigrants, who were usually very poor. Due to this poverty, many of the criminals in Rio de Janeiro were Portuguese immigrants: of the men convicted of crimes there during the four years from 1915 to 1918, 32% were Portuguese (although Portuguese immigrants made up only 15% of the male population of Rio de Janeiro in 1920): 47% of counterfeiters, 43% of arsonists and 23% of convicted murderers were Portuguese. Exactly half of the 220 individuals convicted of manslaughter were Portuguese and 54% of the 1,024 individuals who were serving sentences in prison for assault were also from Portugal. Over time, endogamy became less frequent among Portuguese immigrants, even though they remained as the European group that least married Brazilians in Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo records. Only the Japanese immigrants had higher levels of endogamy in Brazil.[18]

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||