Red meat: Difference between revisions

Niceguyedc (talk | contribs) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Other uses}} |

{{Other uses}} |

||

'''Red meat''' in traditional [[culinary]] terminology is [[meat]] which is red when raw |

'''Red meat''' in traditional [[culinary]] terminology is [[meat]] which is red when raw. In the [[nutrition]]al sciences, red meat includes ''some'' mammal meat. Red meat includes the meat of most adult mammals and some fowl (e.g. [[duck (food)|ducks]]). |

||

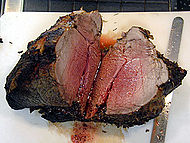

[[Image:Standing-rib-roast.jpg|thumb|190px|An uncooked [[rib roast]].]] |

[[Image:Standing-rib-roast.jpg|thumb|190px|An uncooked [[rib roast]].]] |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

==Definitions== |

==Definitions== |

||

=== Gastronomic === |

=== Gastronomic === |

||

In [[gastronomy]], red meat is darker-colored meat, as contrasted with [[white meat]]. The exact definition varies by time, place, and culture, but the meat of adult mammals such as [[beef|cows]], [[mutton|sheep]], and [[horse meat|horses]] is invariably considered red, while [[chicken]] and [[rabbit]] is invariably considered white. The meat of young mammals such as milk-fed [[veal|veal calves]], [[lamb (meat)|sheep]], and [[pork|pigs]] is traditionally considered |

In [[gastronomy]], red meat is darker-colored meat, as contrasted with [[white meat]]. The exact definition varies by time, place, and culture, but the meat of adult mammals such as [[beef|cows]], [[mutton|sheep]], and [[horse meat|horses]] is invariably considered red, while [[chicken]] and [[rabbit]] is invariably considered white. The meat of young mammals such as milk-fed [[veal|veal calves]], [[lamb (meat)|sheep]], and [[pork|pigs]] is traditionally considered red; while the meat of [[duck (food)|duck]] and [[goose]] is considered white.<ref>[[Oxford English Dictionary]], Second Edition, 1989</ref> [[Game (food)|Game]] is sometimes put in a separate category altogether (French ''viandes noires'' 'black meats').<ref>[[Larousse Gastronomique]], first edition</ref> |

||

Red meat does not refer to how well a piece of meat is cooked. Nor does it refer to its coloration after it has been cooked. |

Red meat does not refer to how well a piece of meat is cooked. Nor does it refer to its coloration after it has been cooked. |

||

Revision as of 01:19, 20 February 2012

Red meat in traditional culinary terminology is meat which is red when raw. In the nutritional sciences, red meat includes some mammal meat. Red meat includes the meat of most adult mammals and some fowl (e.g. ducks).

Definitions

Gastronomic

In gastronomy, red meat is darker-colored meat, as contrasted with white meat. The exact definition varies by time, place, and culture, but the meat of adult mammals such as cows, sheep, and horses is invariably considered red, while chicken and rabbit is invariably considered white. The meat of young mammals such as milk-fed veal calves, sheep, and pigs is traditionally considered red; while the meat of duck and goose is considered white.[1] Game is sometimes put in a separate category altogether (French viandes noires 'black meats').[2]

Red meat does not refer to how well a piece of meat is cooked. Nor does it refer to its coloration after it has been cooked.

Nutritional

The main determinant of the nutritional definition of the color of meat is the concentration of myoglobin. The white meat of chicken has under 0.05%; pork and veal have 0.1-0.3%; young beef has 0.4-1.0%; and old beef has 1.5-2.0%.[3]

According to the USDA all meats obtained from livestock are red meats because they contain more myoglobin than chicken or fish.[4]

Nutrition

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2011) |

Red meat is a source of iron. Red meat also contains protein, levels of creatine, minerals such as zinc and phosphorus, and vitamins such as niacin, vitamin B12, thiamin and riboflavin.[5] Red meat is the richest source of Alpha Lipoic Acid, a powerful antioxidant.[6]

Food pyramid

The 1992 edition of the USDA food guide pyramid has been criticized for not distinguishing between red meat and other types of meat.[7] The 2005 edition, MyPyramid, recommends lean forms of red meat.[8]

Health risks

Colorectal Cancer

Due to the many studies that have found a link between red meat intake and colorectal cancer,[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16] the American Institute for Cancer Research and World Cancer Research Fund stated that there is "convincing" evidence that red meat intake increases the risk for colorectal cancer.[17]

Professor Sheila Bingham of the Dunn Human Nutrition Unit attributes this to the haemoglobin and myoglobin molecules which are found in red meat. She suggests these molecules, when ingested trigger a process called nitrosation in the gut which leads to the formation of carcinogens.[18][19][20] Others have suggested that it is due to the presence of carcinogenic compounds called heterocyclic amines, which are created in the cooking process.[10][21][22] However, this may not be limited to red meat, since a study from the Harvard School of Public Health found that people who ate skinless chicken five times or more per week had a 52% higher risk of developing bladder cancer.[23]

A 2011 study of 17,000 individuals found that people consuming the most grilled and well-done meat had a 56 and 59% higher rate of cancer.[24]

Other Cancers

There is "suggestive" evidence that red meat intake increases the risk of oesophageal, lung, pancreatic and endometrial cancer.[17] As a result, they recommend limiting intake of red meat to less than 300g (11 oz) cooked weight per week, "very little, if any of which to be processed."[25]

Some studies have linked consumption of large amounts of red meat with breast cancer,[26][27] stomach cancer,[28] lymphoma,[29] bladder cancer,[30] lung cancer[31] and prostate cancer[30][32][33] (although other studies have found no relationship between red meat and prostate cancer[34][35]).

A 2009 study by the National Cancer Institute revealed a correlation between the consumption of red meat and increased mortality from cancer, as well as increased mortality from all causes.[36] This study has been criticized for using an improperly validated food frequency questionnaire,[37] which has been shown to have low levels of accuracy.[38][39]

A 2011 study of almost 500,000 participants found that those in the highest quintile of red meat consumption had a 19% increased risk of kidney cancer.[40]

Cardiovascular diseases

Some studies have associated red meat consumption with cardiovascular diseases, possibly because of its high content of saturated fat.[30] Specifically, increased beef intake is associated with ischemic heart disease.[30] Some mechanisms that have been suggested for why red meat consumption is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease include: its impact on serum cholesterol,[41] that red meat contains arachidonic acid,[42] heme iron,[43] and homocysteine.[44] A later study has indicated that it is not associated with cardiovascular diseases.[45]

A 1999 study funded by the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, an advocacy group for beef producers, involved 191 persons with high cholesterol on diets where at least 80% of the meat intake came from either lean red meat in one group, or lean white meat in another. The results of this study showed nearly identical cholesterol, and triglyceride levels in both groups. This study suggests that lean red meat may play a role in a low-fat diet for persons with high cholesterol.[46][47]

Red meat consumption is also associated with acute coronary syndrome,[48] as well as stroke.[49] It has also been associated with greater intima-media thickness, an indicator of atherosclerosis.[50]

A 2008 article published in Nature found that red meat consumption was "strongly associated" with increased odds of acute coronary syndrome, with those eating more than 8 servings of red meat per month being 4.9 times more likely to have cardiac events than those eating less than four servings per month.[51]

A 21 year follow up of about thirty thousand Seventh Day Adventists (adventists are known for presenting a "health message" that recommends vegetarianism) found that people who ate red meat daily were 60% more likely to die of heart disease than those who ate red meat less than once per week.[52]

The Seven Countries Study found a significant correlation between red meat consumption and risk of CHD.[53] A significant relationship between red meat and CHD has been found specifically for women,[54] most strongly with regards to processed red meat.[55]

A 2009 study by the National Cancer Institute revealed a correlation between the consumption of red meat and increased mortality from cardiovascular diseases, as well as increased mortality from all causes.[36] This study has been criticized for using an improperly validated food frequency questionnaire,[37] which has been shown to have low levels of accuracy.[38][39]

Diabetes

Red meat intake has been associated with an increased risk of type II diabetes.[56][57][58] Interventions in which red meat is removed from the diet can lower albuminuria levels.[59] Replacing red meat with a low protein or chicken diet can improve glomerular filtration rate.[60]

Other findings have suggested that the association may be to saturated fat, trans fat and dietary cholesterol, rather than red meat per se.[61][62][63] An additional confound is that diets high in processed meat could increase the risk for developing Type 2 diabetes.[64]

One study estimated that “substitutions of one serving of nuts, low-fat dairy, and whole grains per day for one serving of red meat per day were associated with a 16–35% lower risk of type two diabetes”.[65]

Obesity

The Diogenes project used data from ninety thousand men and women over about seven years and found that "higher intake of total protein, and protein from animal sources was associated with subsequent weight gain for both genders, strongest among women, and the association was mainly attributable to protein from red and processed meat and poultry rather than from fish and dairy sources. There was no overall association between intake of plant protein and subsequent changes in weight."[66] They also found an association between red meat consumption and increased waist circumference.

A 1998 survey of about five thousand vegetarian and non-vegetarian people found that vegetarians had about 30% lower BMIs.[67] A 2006 survey of fifty thousand women found that those with higher "western diet pattern" scores gained about two more kilograms over the course of four years than those who lowered their scores.[68]

A ten-year follow up of 80,000 men and women found that "ten-year changes in body mass index was associated positively with meat consumption" as well as with weight gain at the waist.[69] In a Mediterranean population of 8,000 men and women, meat consumption was significantly associated with weight gain.[70] Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey showed "consistent positive associations between meat consumption and BMI, waist circumference, obesity and central obesity."[71]

A survey of twins found that processed meat intake was associated with weight gain.[72] Western diets, which include higher consumption of red meats, are often associated with obesity.[73][74]

Other health issues

Regular consumption of red meat has also been linked to hypertension,[30] and arthritis.[30][75]

Culture

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (July 2011) |

In some cultures, eating red meat is considered a masculine activity, possibly due to traditions of hunting big game as a male rite of passage.[76]

See also

References

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition, 1989

- ^ Larousse Gastronomique, first edition

- ^ "Iowa State Animal Science". Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ "USDA-Safety of Fresh Pork...from Farm to Table". Fsis.usda.gov. 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2009-09-16.

- ^ Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service, Red Meats: Nutrient Contributions to the Diet, September 1990, http://www.oznet.ksu.edu/library/fntr2/mf974.pdf

- ^ The Nutrition Reporter newsletter, Alpha-Lipoic Acid: Quite Possibly the "Universal" Antioxidant, July 1996, http://www.thenutritionreporter.com/Alpha-Lipoic.html

- ^ Harvard School of Public Health, Food Pyramids: What Should You Really Eat, 2008, http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/what-should-you-eat/pyramid-full-story/index.html

- ^ United States Department of Agriculture, Inside the Pyramid, 2005, http://www.mypyramid.gov/pyramid/meat.html

- ^ Eating Lots of Red Meat Linked to Colon Cancer, American Cancer Society

- ^ a b "Red meat 'linked to cancer risk'". BBC News. 2005-06-15.

- ^ Sinha, R. et al. “Well-done, grilled red meat increases the risk of colorectal adenomas.” Cancer Research 59.17 (1999): 4320.

- ^ Giovannucci E., Rimm E. B., Stampfer M. J., Colditz G. A., Ascherio A., Willet W. C. Intake of fat, meat and fiber in relation to risk of colon cancer in men. Cancer Res., 54: 2390-2397, 1994.

- ^ Willet W. C., Stampfer M. J., Colditz G. A., Rosner B. A., Speizer F. E. Relation of meat, fat and fiber intake to the risk of colon cancer in a prospective study among women. N. Engl. J. Med., 323: 1664-1672, 1990.

- ^ Kune, Gabriel A. “The Melbourne Colorectal Cancer Study: reflections on a 30-year experience.” The Medical Journal of Australia 193.11-12 (2010): 648-652.

- ^ Recommendations for Cancer Prevention

- ^ Tavani, A. et al. “Red meat intake and cancer risk: a study in Italy.” International Journal of Cancer 86.3 (2000): 425-428.

- ^ a b Food, Nutrition, Physical Activity, and the Prevention of Cancer: a Global Perspective. p. 116. ISBN 9780972252225.

- ^ "Red meat cancer risk clue found". BBC News. 2006-01-31.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2006.08.025, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1016/j.mehy.2006.08.025instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/carcin/22.10.1653, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/carcin/22.10.1653instead. - ^ Augustsson, K. et al. “Dietary heterocyclic amines and cancer of the colon, rectum, bladder, and kidney: a population-based study.” The Lancet 353.9154 (1999): 703-707.

- ^ Sinha, R., and N. Rothman. “Role of well-done, grilled red meat, heterocyclic amines (HCAs) in the etiology of human cancer.” Cancer letters 143.2 (1999): 189-194.

- ^ Michaud DS. et al. "Meat intake and bladder cancer risk in 2 prospective cohort studies." Am J Clin Nutr. 2006 Nov;84(5):1177-83.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/bjc.2011.549, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/bjc.2011.549instead. - ^ http://www.dietandcancerreport.org/?p=recommendation_05

- ^ Stein, Rob (2006-11-14). "Breast Cancer Risk Linked To Red Meat, Study Finds". The Washington Post.

- ^ Cho, E. et al. “Red meat intake and risk of breast cancer among premenopausal women.” Archives of internal medicine 166.20 (2006): 2253.

- ^ Study Links Meat Consumption to Gastric Cancer, National Cancer Institute

- ^ "Study links red meat to some cancers". CNN.

- ^ a b c d e f Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 10479227, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=10479227instead. - ^ Alavanja, M. C. R. et al. “Lung cancer risk and red meat consumption among Iowa women.” Lung Cancer 34.1 (2001): 37-46.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 8105097, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=8105097instead. - ^ Agalliu, Ilir et al. “Oxidative balance score and risk of prostate cancer: Results from a case-cohort study.” Cancer Epidemiology (2010): n. pag.

- ^ Salem, Sepehr et al. “Major Dietary Factors and Prostate Cancer Risk: A Prospective Multicenter Case-Control Study.” Nutrition and Cancer (2010): 1.

- ^ Alexander, Dominik D et al. “A review and meta-analysis of prospective studies of red and processed meat intake and prostate cancer.” Nutrition Journal 9 (2010): 50.

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19307518, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19307518instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 19752416, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=19752416instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2621022, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2621022instead. - ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11682365, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11682365instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.019364, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3945/ajcn.111.019364instead. - ^ Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, Hunninghake D, Grundy SM, Wilson PW, Clarkson TB et al. (1990). The cholesterol facts. A summary relating dietary fats, serum cholesterol and coronary heart disease. Circulation 81, 1721–1733.

- ^ Leaf A, Weber PC (1988). Cardiovascular effects of n-3 fatty acids. N Engl J Med 318, 549–557.

- ^ Malaviarachchi D, Veugelers PJ, Yip AM, MacLean DR (2002). Dietary iron as a risk factor for myocardial infarction. Public health considerations for Nova Scotia. Can J Public Health 93, 267–270.

- ^ Verhoef P, Stampfer MJ, Buring JE, Gaziano JM, Allen RH, Stabler SP et al. (1996). Homocysteine metabolism and risk of myocardial infarction: relation with vitamins B6 and B12 and folate. Am J Epidemiol 143, 845–859.

- ^ Renata Micha, RD, PhD; Sarah K. Wallace, BA; Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH (2010). Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk of Incident Coronary Heart Disease, Stroke, and Diabetes Mellitus, A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circulation 121, 2271-2283.

- ^ Science Daily, Study Shows Lean Red Meat Can Play A Role In Low-Fat Diet, 1999, http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/07/990702075933.htm

- ^ Davidson MH, Hunninghake D, Maki KC, Kwiterovich PO, Kafonek S (1999). "Comparison of the effects of lean red meat vs lean white meat on serum lipid levels among free-living persons with hypercholesterolemia: a long-term, randomized clinical trial". Arch. Intern. Med. 159 (12): 1331–8. doi:10.1001/archinte.159.12.1331. PMID 10386509.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Kontogianni, M. D. et al. “Relationship between meat intake and the development of acute coronary syndromes: the CARDIO2000 case–control study.” European journal of clinical nutrition 62.2 (2007): 171-177.

- ^ Fung, T. T. et al. “Prospective study of major dietary patterns and stroke risk in women.” Stroke 35.9 (2004): 2014.

- ^ Oh, Sun Min et al. “Association between meat consumption and carotid intima-media thickness in korean adults with metabolic syndrome.” Journal of Preventive Medicine and Public Health = Yebang Ŭihakhoe Chi 43.6 (2010): 486-495

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602713, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602713instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6720674, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=6720674instead. - ^ Menotti A, Kromhout D, Blackburn H, Fidanza F, Buzina R, Nissinen A, for the Seven Countries Study Research Group (1999). Food intake patterns and 25-year mortality from coronary heart disease: Cross-cultural correlations in the Seven Countries Study. Eur J Epidemiol 15, 507–515.

- ^ Zyriax BC, Boeing H, Windler E (2005). Nutrition is a powerful independent risk factor for coronary heart disease in women-The CORA study: a population-based case–control study. Eur J Clin Nutr 59, 1201–1207.

- ^ Gramenzi A, Gentile A, Fasoli M, Negri E, Parazzini F, La Vecchia C (1990). Association between certain foods and risk of acute myocardial infarction in women. BMJ 300, 771–773.

- ^ Song, Y. et al. “A prospective study of red meat consumption and type 2 diabetes in middle-aged and elderly women.” Diabetes Care 27.9 (2004): 2108.

- ^ Fung, T. T. et al. “Dietary patterns, meat intake, and the risk of type 2 diabetes in women.” Archives of internal medicine 164.20 (2004): 2235.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.417, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.3.417instead. - ^ de Mello, V. D. F. et al. “Withdrawal of red meat from the usual diet reduces albuminuria and improves serum fatty acid profile in type 2 diabetes patients with macroalbuminuria.” American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 83.5 (2006): 1032.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2337/diacare.25.4.645, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2337/diacare.25.4.645instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.2337/diacare.25.3.417, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.2337/diacare.25.3.417instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 11508264, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=11508264instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1093/ije/19.4.953, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1093/ije/19.4.953instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1007/s00125-003-1220-7, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1007/s00125-003-1220-7instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.3945/ajcn.111.018978, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.3945/ajcn.111.018978instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.254, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ijo.2010.254instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 9622343, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=9622343instead. - ^ Schulze, M. B. et al. “Dietary Patterns and Changes in Body Weight in Women.” Obesity 14.8 (2006): 1444-1453.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1381044, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=1381044instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 16469996, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=16469996instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.45, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ijo.2009.45instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ijo.2010.1, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ijo.2010.1instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.203;, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ijo.2009.203;instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1038/ijo.2009.179, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1038/ijo.2009.179instead. - ^ Pattison, D. J. et al. “Dietary risk factors for the development of inflammatory polyarthritis: evidence for a role of high level of red meat consumption.” Arthritis & Rheumatism 50.12 (2004): 3804-3812.

- ^ "Real Men Eat Meat". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2009-09-16.