Dallas Love Field: Difference between revisions

Removed clean-up tag |

Cyberbot II (talk | contribs) Rescuing 4 sources. #IABot |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

In January 1921, 1st lt William D. Coney attempted to fly from San Diego to Jacksonville with just one stop—at Love Field.{{r|Maurer}}{{rp|177}} In 1921, the aviation repair depot next to Love Field moved to Kelly Field in San Antonio to consolidate with the supply depot at Kelly, forming the San Antonio Intermediate Air Depot. In 1923, Dallas was a route point between [[Muskogee, Oklahoma|Muskogee]] and [[Kelly Field]] on the southern division of the model airway.{{r|Maurer}}{{rp|152}} However, by 1923, the decision had been made to phase down all activities at the new base in accordance with sharply reduced military budgets and it was closed. The War Department had ordered the small caretaker force at Love Field to dismantle all remaining structures and to sell them as surplus. The War Department leased out the vacant land to local farmers and ranchers |

In January 1921, 1st lt William D. Coney attempted to fly from San Diego to Jacksonville with just one stop—at Love Field.{{r|Maurer}}{{rp|177}} In 1921, the aviation repair depot next to Love Field moved to Kelly Field in San Antonio to consolidate with the supply depot at Kelly, forming the San Antonio Intermediate Air Depot. In 1923, Dallas was a route point between [[Muskogee, Oklahoma|Muskogee]] and [[Kelly Field]] on the southern division of the model airway.{{r|Maurer}}{{rp|152}} However, by 1923, the decision had been made to phase down all activities at the new base in accordance with sharply reduced military budgets and it was closed. The War Department had ordered the small caretaker force at Love Field to dismantle all remaining structures and to sell them as surplus. The War Department leased out the vacant land to local farmers and ranchers |

||

In 1927, Dallas purchased Love Field, which opened for [[civilian]] use (1st passenger service was by the [[National Air Transport]] company.)<ref>Payne, Darwin and Kathy Fitzpatrick (1999), ''From Prairie To Planes'', Three Forks Press.</ref> On April 9, 1932, the first paved runways at the airfield were completed,<ref name="dallas-lovefield.com"> |

In 1927, Dallas purchased Love Field, which opened for [[civilian]] use (1st passenger service was by the [[National Air Transport]] company.)<ref>Payne, Darwin and Kathy Fitzpatrick (1999), ''From Prairie To Planes'', Three Forks Press.</ref> On April 9, 1932, the first paved runways at the airfield were completed,<ref name="dallas-lovefield.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.dallas-lovefield.com/lovenotes/lovechrono.html |title=Archived copy |accessdate=November 24, 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20090505141310/http://dallas-lovefield.com:80/lovenotes/lovechrono.html |archivedate=May 5, 2009 }}</ref> and in March 1939 the airfield had 21 weekday airline departures: 9 [[American Airlines|American]], 8 [[Braniff International Airways|Braniff]] and 4 [[Delta Air Lines|Delta]].<ref>{{Cite report |title=Official Aviation Guide shows |publisher=Official Aviation Guide Company |location=Chicago}}</ref> "On 6 June 1939, the War Department approved...nine civil school detachments", including one at Dallas{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|18}} ([[cf.]] a 1940 school approved for Ft Worth's [[Hicks Field]],{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|26}} a new 1942 [[Naval Air Station Joint Reserve Base Fort Worth|Ft Worth airfield--Tarrant Field]] at the government plant and that had a 4 engine pilots' school,{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|69}}) and a Ferrying Command control center at Dallas' [[Hensley Field]].{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|144}}) |

||

===World War II training and ferrying=== |

===World War II training and ferrying=== |

||

By October 1940 at the [[Texas World War II Army Airfields|Texas World War II Army Airfield]],{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|29}} classes had entered the Dallas Texas Aviation School, which provided basic (level 1) flight training using [[Fairchild PT-19]]s as the primary trainer (several [[PT-17 Stearman]]s and a few [[P-40 Warhawk]]s were also assigned.{{Citation needed|date=October 2013}} The [[Gulf Coast Air Corps Training Center|Gulf Coast ACTC]] school later moved to [[Brady, Texas]];{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|32}} and Love Field also had an [[Air Materiel Command]] modification center.{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|141}} In September 1942, the [[Air Transport Command (United States Air Force)|Air Transport Command]] activity at Hensley Field moved to Love Field.{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|146}} ATC's 5th Ferrying Group, consisting of [[Women Airforce Service Pilots|Women's Auxiliary]] Ferrying Squadrons (WAFS) ferried PT-17s, AT-6s and twin-engine Cessna AT-17s; and Love Field was also used by the San Antonio Air Service Command for aircraft overhauls. The 2d Ferrying Squadron of the 5th Ferrying Group was moved by [[Air Transport Command (United States Air Force)|Air Transport Command]] from Love Field to [[Fairfax Field]] at Kansas City on 15 April 1943.<ref>{{Full citation needed|reason=claim was originally posted to Wikipedia in [[Fairfax Field]] wikiaticle.|date=July 2013}}{{Cite report |url=http://airforcehistoryindex.org/data/000/182/132.xml |format=AFHRA document |title=History of the 33d Ferrying Group}}</ref> |

By October 1940 at the [[Texas World War II Army Airfields|Texas World War II Army Airfield]],{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|29}} classes had entered the Dallas Texas Aviation School, which provided basic (level 1) flight training using [[Fairchild PT-19]]s as the primary trainer (several [[PT-17 Stearman]]s and a few [[P-40 Warhawk]]s were also assigned.{{Citation needed|date=October 2013}} The [[Gulf Coast Air Corps Training Center|Gulf Coast ACTC]] school later moved to [[Brady, Texas]];{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|32}} and Love Field also had an [[Air Materiel Command]] modification center.{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|141}} In September 1942, the [[Air Transport Command (United States Air Force)|Air Transport Command]] activity at Hensley Field moved to Love Field.{{r|Futrell}}{{rp|146}} ATC's 5th Ferrying Group, consisting of [[Women Airforce Service Pilots|Women's Auxiliary]] Ferrying Squadrons (WAFS) ferried PT-17s, AT-6s and twin-engine Cessna AT-17s; and Love Field was also used by the San Antonio Air Service Command for aircraft overhauls. The 2d Ferrying Squadron of the 5th Ferrying Group was moved by [[Air Transport Command (United States Air Force)|Air Transport Command]] from Love Field to [[Fairfax Field]] at Kansas City on 15 April 1943.<ref>{{Full citation needed|reason=claim was originally posted to Wikipedia in [[Fairfax Field]] wikiaticle.|date=July 2013}}{{Cite report |url=http://airforcehistoryindex.org/data/000/182/132.xml |format=AFHRA document |title=History of the 33d Ferrying Group}}</ref> |

||

In September 1943 a new north-south runway 18/36 and northwest-southeast runway 13/31 were completed. Air Force facilities closed at the end of WWII<ref>Manning, Thomas A. (2005), ''History of Air Education and Training Command, 1942–2002''. Office of History and Research, Headquarters, AETC, Randolph AFB, Texas ASIN: B000NYX3PC</ref><ref>Shaw, Frederick J. (2004), ''Locating Air Force Base Sites'' History’s Legacy, Air Force History and Museums Program, United States Air Force, Washington D.C., 2004.</ref> except for Love Field's [[:Category:United States automatic tracking radar stations|automatic tracking radar station]] ([[call sign]] Dallas Bomb Plot) for [[Radar Bomb Scoring]] that had been established by June 6, 1945{{r|Summary}} (transferred to [[Strategic Air Command]] on March 21, 1946, 10th RBSS Det 1 by 1957.)<ref> |

In September 1943 a new north-south runway 18/36 and northwest-southeast runway 13/31 were completed. Air Force facilities closed at the end of WWII<ref>Manning, Thomas A. (2005), ''History of Air Education and Training Command, 1942–2002''. Office of History and Research, Headquarters, AETC, Randolph AFB, Texas ASIN: B000NYX3PC</ref><ref>Shaw, Frederick J. (2004), ''Locating Air Force Base Sites'' History’s Legacy, Air Force History and Museums Program, United States Air Force, Washington D.C., 2004.</ref> except for Love Field's [[:Category:United States automatic tracking radar stations|automatic tracking radar station]] ([[call sign]] Dallas Bomb Plot) for [[Radar Bomb Scoring]] that had been established by June 6, 1945{{r|Summary}} (transferred to [[Strategic Air Command]] on March 21, 1946, 10th RBSS Det 1 by 1957.)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.afmissileers.org/newsletters/NL1997/Dec97.pdf |title=Archived copy |accessdate=October 9, 2013 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20131005021555/http://www.afmissileers.org/newsletters/NL1997/Dec97.pdf |archivedate=October 5, 2013 }}</ref> |

||

===1940 to 1957=== |

===1940 to 1957=== |

||

| Line 130: | Line 130: | ||

[[Southwest Airlines]], founded in 1971 and headquartered at Love Field, built its business on selling quick, no-frills trips between Dallas, [[Houston, Texas|Houston]], and [[San Antonio, Texas|San Antonio]]. The company felt that the notion of a quick trip would be destroyed by a long drive to the new airport. Prior to the opening of DFW, Southwest Airlines sued for the right to remain at Love Field. In 1973 the courts ruled that the City of Dallas could not restrict Southwest Airlines from operating out of Love Field, so long as it remained open as an airport. This ruling effectively granted Southwest the right to continue to operate its existing intrastate service out of Love Field. The airlines operating from Love Field at the time DFW was conceived executed agreements with DFW stipulating that no airline could operate at the new airport if it continued to operate any flights out of Love Field. Southwest, created after the other carriers had signed on to the DFW operating agreements, was not a signatory and remained as the only airline operating at Love Field.<ref name="dallas-lovefield.com"/> |

[[Southwest Airlines]], founded in 1971 and headquartered at Love Field, built its business on selling quick, no-frills trips between Dallas, [[Houston, Texas|Houston]], and [[San Antonio, Texas|San Antonio]]. The company felt that the notion of a quick trip would be destroyed by a long drive to the new airport. Prior to the opening of DFW, Southwest Airlines sued for the right to remain at Love Field. In 1973 the courts ruled that the City of Dallas could not restrict Southwest Airlines from operating out of Love Field, so long as it remained open as an airport. This ruling effectively granted Southwest the right to continue to operate its existing intrastate service out of Love Field. The airlines operating from Love Field at the time DFW was conceived executed agreements with DFW stipulating that no airline could operate at the new airport if it continued to operate any flights out of Love Field. Southwest, created after the other carriers had signed on to the DFW operating agreements, was not a signatory and remained as the only airline operating at Love Field.<ref name="dallas-lovefield.com"/> |

||

1973 saw Love Field, which had more than 70 gates and saw frequent [[Boeing 747]] service, reach record enplanements at 6,668,398 as the eighth busiest airport in the United States. On January 13, 1974 DFW Airport opened, ending most passenger service at Love Field.<ref name="dallas-lovefield.com"/><ref name="dallasnews.com"> |

1973 saw Love Field, which had more than 70 gates and saw frequent [[Boeing 747]] service, reach record enplanements at 6,668,398 as the eighth busiest airport in the United States. On January 13, 1974 DFW Airport opened, ending most passenger service at Love Field.<ref name="dallas-lovefield.com"/><ref name="dallasnews.com">{{cite web|url=http://www.dallasnews.com/sharedcontent/dws/bus/stories/012209dnbuslovefield.3e8a922.html |title=Archived copy |accessdate=November 24, 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20100115222018/http://www.dallasnews.com:80/sharedcontent/dws/bus/stories/012209dnbuslovefield.3e8a922.html |archivedate=January 15, 2010 }}</ref> |

||

===1974 through 1999=== |

===1974 through 1999=== |

||

| Line 173: | Line 173: | ||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

In early 2009 a plan to modernize Love Field was announced. The $519 million master plan will replace the existing terminals with a new 20-gate concourse and expanded baggage facilities.<ref name="dallasnews.com"/> The project also called for a $250 million [[people mover]] system to connect to [[Dallas Area Rapid Transit]]'s [[Burbank Station]],<ref> |

In early 2009 a plan to modernize Love Field was announced. The $519 million master plan will replace the existing terminals with a new 20-gate concourse and expanded baggage facilities.<ref name="dallasnews.com"/> The project also called for a $250 million [[people mover]] system to connect to [[Dallas Area Rapid Transit]]'s [[Burbank Station]],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dallascityhall.com/committee_briefings/briefings0209/TEC_3Program_Mgr_022309.pdf |title=Archived copy |accessdate=November 24, 2009 |deadurl=yes |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20100114021902/http://dallascityhall.com/committee_briefings/briefings0209/TEC_3Program_Mgr_022309.pdf |archivedate=January 14, 2010 }}</ref> but this was eliminated in favor of a cheaper bus connection to the Inwood Station.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://dartdallas.dart.org/2014/02/03/ask-dart-will-dallas-love-field-service-change-when-the-wright-amendment-ends/|title=Ask DART: Will Dallas Love Field service change when the Wright Amendment ends?|first=Travis|last=Hudson|date=3 February 2014|website=Dartdallas.dart.org|accessdate=10 June 2016}}</ref> |

||

The airport became embroiled in a controversy over [[Concession (contract)|concessions contracts]] when Dallas mayor [[Tom Leppert]], during a March 3, 2010, City Council meeting, abruptly withdrew support for no-bid contracts with current airport food vendor Star Concessions Ltd. and newspaper and book vendor Hudson Retail Dallas, insisting that the contracts should be opened to public [[bidding]] instead. At a February 22, 2010, meeting, the City Council recommended that the existing contracts, set to expire in June 2011, be extended until 2026 with an additional three-year option and exclusive rights to 54 percent of vending space in a new terminal scheduled to open in 2014.<ref name="do1">{{cite news |author=Sam Merten|title=The Battle Over Airport Contracts Opens a Rift Between the Mayor and Minority City Council Members.|work=[[Dallas Observer]] |date=2010-06-17}}</ref> After several abortive attempts to resolve the issue, the City Council voted on August 18, 2010, to open all concessions space in the new terminal for public bidding; city staff would attempt to reach a deal with Star and Hudson to operate existing concessions space from 2011 to 2014, otherwise it would also be opened for public bidding.<ref>{{cite news |author=Rudolph Bush |title=Love Field no-bid concessions contracts defeated at City Hall|work=[[The Dallas Morning News]] |date=2010-08-19}}</ref> |

The airport became embroiled in a controversy over [[Concession (contract)|concessions contracts]] when Dallas mayor [[Tom Leppert]], during a March 3, 2010, City Council meeting, abruptly withdrew support for no-bid contracts with current airport food vendor Star Concessions Ltd. and newspaper and book vendor Hudson Retail Dallas, insisting that the contracts should be opened to public [[bidding]] instead. At a February 22, 2010, meeting, the City Council recommended that the existing contracts, set to expire in June 2011, be extended until 2026 with an additional three-year option and exclusive rights to 54 percent of vending space in a new terminal scheduled to open in 2014.<ref name="do1">{{cite news |author=Sam Merten|title=The Battle Over Airport Contracts Opens a Rift Between the Mayor and Minority City Council Members.|work=[[Dallas Observer]] |date=2010-06-17}}</ref> After several abortive attempts to resolve the issue, the City Council voted on August 18, 2010, to open all concessions space in the new terminal for public bidding; city staff would attempt to reach a deal with Star and Hudson to operate existing concessions space from 2011 to 2014, otherwise it would also be opened for public bidding.<ref>{{cite news |author=Rudolph Bush |title=Love Field no-bid concessions contracts defeated at City Hall|work=[[The Dallas Morning News]] |date=2010-08-19}}</ref> |

||

Revision as of 22:04, 10 June 2016

Dallas Love Field | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

2013 aerial photo | |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | City of Dallas | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Dallas Department of Aviation | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | Dallas–Fort Worth–Arlington | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Dallas, Texas, USA | ||||||||||||||||||

| Focus city for | |||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 487 ft / 148 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 32°50′50″N 096°51′06″W / 32.84722°N 96.85167°W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | www.dallas-lovefield.com | ||||||||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||||||||

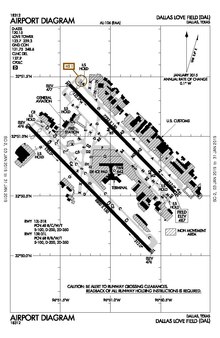

FAA airport diagram | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2007, 2013[1]) | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Dallas Love Field (IATA: DAL, ICAO: KDAL, FAA LID: DAL) is a city-owned public airport 6 miles (10 km) northwest of downtown Dallas, Texas.[2] It was Dallas' main airport until 1974 when Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport (DFW) opened.

The corporate headquarters for Southwest Airlines is located at Love Field. The airport is also a focus city for Southwest as well as for Virgin America. Seven full-service fixed-base operators (FBOs) provide general aviation service: fuel, maintenance, hangar rentals, and charters. Some also provide meeting rooms, car rentals, limousine service and restaurants.

History

Dallas Love Field is named after Moss L. Love,[3] who while assigned to the U.S. Army 11th Cavalry, died in an airplane crash near San Diego, California on September 4, 1913, becoming the 10th fatality in U.S. army aviation history. His Wright Model C biplane crashed during practice for his Military Aviator Test.[4] Love Field was named by the United States Army on October 19, 1917.

World War I

Dallas Love Field has its origins beginning in 1917 when the Army announced its intention of establishing a series of camps to train prospective pilots after the United States entry into World War I. The airfield was one of thirty-two new Air Service fields.[5] It was constructed just southeast of Bachman Lake, and it covered over 700 acres and could accommodate up to 1,000 personnel. Dozens of wooden buildings served as headquarters, maintenance, and officers’ quarters. Enlisted men had to bivouac in tents.[6]

Love Field served as a base for flight training for the United States Army Air Service. In 1917, flight training occurred in two phases: primary and advanced. Primary training took eight weeks and consisted of pilots learning basic flight skills under dual and solo instruction. After completion of their primary training at Love Field, flight cadets were then transferred to another base for advanced training.[6]

After officially opening on October 19, 1917, the first unit stationed at Love Field was the 136th Aero Squadron, which was transferred from Kelly Field, south of San Antonio, Texas. Only a few U.S. Army Air Service aircraft arrived with the 136th Aero Squadron, and most of the Curtiss JN-4 Jennys to be used for flight training were shipped in wooden crates by railcar.[6] Training units assigned to Love Field during World War I were:[7]

- Post Headquarters, Love Field, October 1917-December 1919

- 71st Aero Squadron (II), February 1918

- Re-designated as Squadron "A", July–November 1918

- 121st Aero Squadron (II), April 1918

- Re-designated as Squadron "B", July–November 1918

- 136th Aero Squadron (II), November 1917

- Re-designated as Squadron "C", July–November 1918

- 197th Aero Squadron, November 1917

- Re-designated as Squadron "D", July–November 1918

- Flying School Detachment (Consolidation of Squadrons A-D), November 1918-November 1919

The 865th Aero Squadron (Repair), was formed at Love Field in March 1918 as a support unit for JN-4 aircraft repair and maintenance. It was assigned to the Aviation Repair Depot, Dallas Texas (at Love Field) in April 1918. It was demobilized in March 1919.

With the sudden end of World War I in November 1918, the future operational status of Love Field was unknown. Many local officials speculated that the U.S. government would keep the field open because of the outstanding combat record established by Love-trained pilots in Europe. Locals also pointed to the optimal weather conditions in the Dallas area for flight training. Cadets in flight training on 11 November 1918 were allowed to complete their training, however no new cadets were assigned to the base. Also the separate training squadrons were consolidated into a single Flying School detachment, as many of the personnel assigned were being demobilized.[6]

Inter-war years

With the end of World War I, in December 1919 Love Field was deactivated as an active duty airfield, however, and a small caretaker unit was assigned to the facility for administrative reasons. The facility was converted into a storage facility for surplus De Havilland and JN-4 aircraft were stored at Love Field (some JN-4s were bought back by the Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company in the spring of 1919.)[8]: 12 Post-war "the largest recruiting mission in the spring and summer of 1919" was led by Lt. Col. Henry B. Clagett beginning with seven DH-4s departing Dallas and flying as far as Boston.[8]: 8 A small caretaker unit was assigned to the facility for administrative reasons and it was used intermittently to support small military units.

In January 1921, 1st lt William D. Coney attempted to fly from San Diego to Jacksonville with just one stop—at Love Field.[8]: 177 In 1921, the aviation repair depot next to Love Field moved to Kelly Field in San Antonio to consolidate with the supply depot at Kelly, forming the San Antonio Intermediate Air Depot. In 1923, Dallas was a route point between Muskogee and Kelly Field on the southern division of the model airway.[8]: 152 However, by 1923, the decision had been made to phase down all activities at the new base in accordance with sharply reduced military budgets and it was closed. The War Department had ordered the small caretaker force at Love Field to dismantle all remaining structures and to sell them as surplus. The War Department leased out the vacant land to local farmers and ranchers

In 1927, Dallas purchased Love Field, which opened for civilian use (1st passenger service was by the National Air Transport company.)[9] On April 9, 1932, the first paved runways at the airfield were completed,[10] and in March 1939 the airfield had 21 weekday airline departures: 9 American, 8 Braniff and 4 Delta.[11] "On 6 June 1939, the War Department approved...nine civil school detachments", including one at Dallas[12]: 18 (cf. a 1940 school approved for Ft Worth's Hicks Field,[12]: 26 a new 1942 Ft Worth airfield--Tarrant Field at the government plant and that had a 4 engine pilots' school,[12]: 69 ) and a Ferrying Command control center at Dallas' Hensley Field.[12]: 144 )

World War II training and ferrying

By October 1940 at the Texas World War II Army Airfield,[12]: 29 classes had entered the Dallas Texas Aviation School, which provided basic (level 1) flight training using Fairchild PT-19s as the primary trainer (several PT-17 Stearmans and a few P-40 Warhawks were also assigned.[citation needed] The Gulf Coast ACTC school later moved to Brady, Texas;[12]: 32 and Love Field also had an Air Materiel Command modification center.[12]: 141 In September 1942, the Air Transport Command activity at Hensley Field moved to Love Field.[12]: 146 ATC's 5th Ferrying Group, consisting of Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadrons (WAFS) ferried PT-17s, AT-6s and twin-engine Cessna AT-17s; and Love Field was also used by the San Antonio Air Service Command for aircraft overhauls. The 2d Ferrying Squadron of the 5th Ferrying Group was moved by Air Transport Command from Love Field to Fairfax Field at Kansas City on 15 April 1943.[13]

In September 1943 a new north-south runway 18/36 and northwest-southeast runway 13/31 were completed. Air Force facilities closed at the end of WWII[14][15] except for Love Field's automatic tracking radar station (call sign Dallas Bomb Plot) for Radar Bomb Scoring that had been established by June 6, 1945[16] (transferred to Strategic Air Command on March 21, 1946, 10th RBSS Det 1 by 1957.)[17]

1940 to 1957

On October 6, 1940, Love Field's Lemmon Avenue Terminal Building opened on the east side of the airfield.

On November 29, 1949 American Airlines Flight 157, a Douglas DC-6 en route from New York City to Dallas and Mexico City with 46 passengers and crew, slid off Runway 36 after the flight crew lost control on final approach. The airliner struck a parked airplane, a hangar, and a flight school before crashing into a business across from the airport,[N 1] killing 28. This was the deadliest air disaster in Texas history at the time[18] and, according to modern reference sources,[19] remains the deadliest crash to take place at the airfield itself.

Pioneer Airlines moved its base from Houston to Love Field in 1950.[10]

In 1953, Fort Worth officially opened Amon Carter Field, which would later become Greater Southwest International Airport to compete directly with Love Field. Fort Worth had attempted to negotiate with Dallas to collaborate on the new airport, however Dallas repeatedly declined those attempts. Upon completion, all of the passenger airlines were transferred to Greater Southwest from Meacham, leaving Love Field and Greater Southwest as the only air transportation options for the Dallas-Fort Worth area.

The February 1953 C&GS diagram shows runway 7 (4301 ft), runway 13 (6201 ft) and runway 18 (5202 ft). On June 1, 1954 Runway 7/25 was closed;[10] it was later removed to allow terminal expansion. Love Field then had two runways: Runway 13/31, the main runway, and the shorter 18/36.

The April 1957 Official Airline Guide shows 52 weekday departures on Braniff, 45 on American, 25 Delta, 21 Trans-Texas, 12 Central and 9 Continental.[20] Three nonstops a day to Washington DC, three to New York/Newark, six to Chicago, five to California and 12 a week to Mexico City.

1957 to 1974

Love Field's new terminal (the third terminal, designed by Donald S. Nelson[21]) opened to the airlines on January 20, 1958[10] with three one-story concourses, 26 ramp-level gates and the world's first airport moving walkways.[22] Airlines serving the airport at the time included American, Braniff, Central (which was based in Fort Worth), Continental, Delta and Trans Texas (later Texas International).

Turbine-power flights began on April 1, 1959 when Continental Airlines introduced the Vickers Viscount turboprop. Jet airline flights began on July 12, 1959 when American Airlines started Boeing 707 flights to New York.

In 1961 Mr. and Mrs. Earle Wyatt gave a large bronze statue bearing the inscription "One Riot, One Ranger" for display in the airport's new terminal. Famed Texas born sculptress Waldine Tauch created the piece. The inscription refers to an incident in which a single Texas Ranger was dispatched to quell a riot.[10] Because of terminal renovation from 2010 to 2013, the statue was moved temporarily for display to the nearby Frontiers of Flight Museum, but the statue has now been returned to a prominent location in the lobby of terminal one (August 2013).

On November 22, 1963 President John F. Kennedy arrived at Love Field on Air Force One, and was assassinated in Dealey Plaza while his motorcade was traveling from Love Field to the Dallas Trade Mart. Hours later, Lyndon B. Johnson was sworn in as president aboard Air Force One before its departure from Love Field.

On April 2, 1965 the 8,800 ft (2,682 m) parallel Runway 13R/31L opened (Runway 13/31 became Runway 13L/31R).[23] The project had been vexed by legal wrangling; safety concerns were raised regarding its proximity to schools[24] and its minimal safety areas,[25] while nearby residents attempted to stop the anticipated increase in jet noise and the removal of homes and businesses adjacent to the airport to accommodate the project.[26][27]

Several terminal expansion programs were fueled by the boom in air travel during the 1960s. American Airlines expanded their concourse in 1968 and Braniff opened its "Terminal of the Future." The expansion, showcasing Alexander Girard, Herman Miller and Ray and Charles Eames designs, featured the first rotunda concourse, jet bridges and several airport innovations. Braniff connected their new terminal to new remote parking lots with the Jetrail monorail system in 1970.[28] Texas International expanded their concourse in 1969, and Delta's concourse was expanded in 1970.[10] By 1972, American used 14 gates on the west end of the terminal, Delta used 13 gates, Braniff and Ozark together used 13 gates on the east end of the terminal, and Texas International used seven gates.[29]

In 1972 Love Field saw an hijacking incident. On 12 January, Billy Gene Hurst, Jr., a resident of Houston, hijacked Braniff Flight 38, a Boeing 727 airliner, as it departed William P. Hobby Airport in Houston bound for Dallas. After the plane landed at Love Field, Hurst allowed all 94 passengers to deplane, but continued to hold the 7 crewmembers hostage. Hurst insisted on flying to South America and made a variety of other demands, including food, cigarettes, parachutes, jungle survival gear, US $2 million, and a handgun. After a 6-hour standoff, police gave Hurst a package containing parachutes and some other items, and the hostages escaped while he was distracted examining the package's contents. Police stormed the craft soon afterwards and arrested him without serious incident. He was later sentenced to 20 years in prison.[30][31][32][33]

In 1964, the FAA, tired of having to fund separate airports in Dallas and Fort Worth, gave the two cities a six-month period to choose a site for and plan out a new regional airport. Ultimately, they agreed to build Dallas/Fort Worth Regional Airport (now Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport). It was agreed that to promote the new airport, each city would restrict its own passenger-service airports from air-carrier operations. Soon after the new airport opened, Greater Southwest was immediately closed to passenger traffic and its runways painted with large X's to avoid confusing pilots and due to the fact that Greater Southwest's runways were directly in the flight path of the new airport. By 1974, Greater Southwest International Airport was unceremoniously closed for good. The art-deco terminal was torn down in 1980.

Southwest Airlines, founded in 1971 and headquartered at Love Field, built its business on selling quick, no-frills trips between Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio. The company felt that the notion of a quick trip would be destroyed by a long drive to the new airport. Prior to the opening of DFW, Southwest Airlines sued for the right to remain at Love Field. In 1973 the courts ruled that the City of Dallas could not restrict Southwest Airlines from operating out of Love Field, so long as it remained open as an airport. This ruling effectively granted Southwest the right to continue to operate its existing intrastate service out of Love Field. The airlines operating from Love Field at the time DFW was conceived executed agreements with DFW stipulating that no airline could operate at the new airport if it continued to operate any flights out of Love Field. Southwest, created after the other carriers had signed on to the DFW operating agreements, was not a signatory and remained as the only airline operating at Love Field.[10]

1973 saw Love Field, which had more than 70 gates and saw frequent Boeing 747 service, reach record enplanements at 6,668,398 as the eighth busiest airport in the United States. On January 13, 1974 DFW Airport opened, ending most passenger service at Love Field.[10][34]

1974 through 1999

With the drastic reduction in flights and only 467,212 enplanements in 1975,[10] Love Field decommissioned several of its concourses. The city of Dallas attempted to make use of these dormant facilities by leasing some of them to an entrepreneur who opened the "Love Entertainment Complex" in November 1975. The main lobby at the front of a former terminal was transformed into movie theaters, ice rink, roller rink, huge video arcades, restaurants and bowling alley. Love seemed especially suited for the pre-teen and teen crowd, who could spend the day for a single admission charge of about $3.50. Love closed in May 1978.[citation needed] Several of the concourses were remodeled into support and training buildings for Southwest Airlines.

After deregulation of the U.S. airline industry in 1978, Southwest Airlines was able to enter the larger passenger markets and announced plans to start providing interstate service in 1979. This angered the City of Fort Worth and DFW International Airport, which resented expanded air service at Love Field. Therefore, Fort Worth-based U.S. Representative (later Speaker of the House) Jim Wright helped get a "compromise" law through Congress that restricted air service at Love Field. Using the pretext of protecting DFW, the Wright Amendment restricted passenger air traffic out of Love Field in the following ways: Passenger service on regular mid-sized and large aircraft could only be provided from Love Field to locations within Texas and four neighboring states (Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico). Long-haul service to other states was possible, but only on commuter aircraft with no more capacity than 56 passengers.[35]

While the Wright Amendment prevented any other major airlines from starting service out of Love Field, it did not deter Southwest. Based on short trips to begin with, Southwest continued to flourish as it used multiple shorthaul flights to build its Love Field operation. Some people managed to "work the system" and get around the Wright Amendment's restrictions. For example, a person could fly from Dallas to Houston or Albuquerque, change planes, and then fly to any city Southwest served — although he had, at the time, to do so on two tickets in each direction, since the Wright Amendment specifically barred airlines from issuing tickets that violated the law's provisions. This work around was also problematic due to the fact that between flights checked baggage had to be collected and checked onto the next flight. This had the effect of creating mini-hubs at Houston/Hobby Airport and the Albuquerque International Sunport. Southwest continued to grow and became one of the most successful and profitable airlines in the United States.[citation needed]

Due to the success of Southwest Airlines, other airlines began considering the use of Love Field for short haul trips. Southwest co-founder Lamar Muse started Muse Air, a short haul competitor using DC-9s and MD-80s between Love Field and Houston in 1982. Muse Air was unable to operate profitably against Southwest at Love Field, and was purchased by Southwest in 1985 and renamed TranStar Airlines. Southwest ceased Transtar operations in 1987. Continental Airlines expressed its intent to fly out of Love Field in 1985, which led to years of court battles over the interpretation of the Wright Amendment as Fort Worth and DFW International Airport continued to try to prevent expansion at Love Field. Seeing the benefit of increased air traffic at Love Field, the City of Dallas began to actively lobby for the repeal of the Wright Amendment restrictions in 1992. In 1997 the Shelby Amendment passed through Congress, amending the Wright Amendment. A compromise of sorts, the Shelby Amendment allowed Love Field flights to three more states, Kansas, Mississippi, and Alabama. It amended the definition of 56-passenger jets that could fly to other states to include any aircraft weighing less than 300,000 pounds with 56 or fewer seats.

The Shelby Amendment caused several airlines to consider flying 56-passenger jets out of Love Field, including Continental, Delta, and a new airline, Legend. The City of Fort Worth immediately sued the City of Dallas to try to prevent the Shelby Amendment from going into effect. American, headquartered at DFW, joined the lawsuits against Dallas, but also said that if other airlines were allowed to fly out of Love Field, it would have no choice but to offer competing service. In 1998, after a year of legal decisions and appeals, Continental Express became the first major airline other than Southwest to fly out of Love Field since 1974. American began service out of Love Field shortly thereafter, but continued to sue to stop the service. Fort Worth and American Airlines eventually sued the U.S. Department of Transportation to stop allowing more flights out of Love Field.

2000 to 2013

In 2000, several federal appeals court decisions finally struck down all lawsuits against the Shelby Amendment. Fort Worth and American Airlines appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which refused to review the case. These legal decisions opened the door to increased long haul flights out of Love Field using 56-passenger jets, including new service by Delta and Legend. The majority of this 56-passenger jet market was composed of business travelers making day trips to other cities.

In 2001, the September 11, 2001, attacks and the subsequent recession greatly reduced the demand for air travel in the U.S., especially within the business traveler market. As a result, most of the airlines providing long haul 56-passenger flights stopped service and pulled out of Love Field. By 2003, Southwest and Continental Express were the only two major commercial airlines operating out of Love Field. However, due to Southwest's success and the possibility of other airlines returning in the future, the airport has completed an expansion of its parking facilities and is redeveloping one of its terminals.

New parking facilities in a 2,400-space garage opened in 2002 and 2003, connected to the terminal with a climate controlled walkway. The East Concourse, formerly Braniff's "Terminal of the Future," was demolished as part of the Love Field Modernization Program.[10]

In 2002, Love Field was designated as a Texas State Historical Site in 2003.

The Frontiers of Flight Museum, which had been located inside the airport terminal since 1988, moved to the north side of the airport in a separate facility.

In November 2004, Southwest announced their active opposition to the Wright Amendment, claiming that the law is anti-competitive and outdated. On November 30, 2005, Missouri was added to the list of states exempted from the Wright Amendment by an amendment written by Sen. Kit Bond. Southwest began nonstop flights to Kansas City and St. Louis on December 13. American Airlines and American Eagle began flights from Love to St. Louis, Kansas City, Austin, and San Antonio on March 2, 2006, although American Airlines subsequently pulled out of the market, leaving American Eagle to offer a reduced service to Austin and Kansas City alone. In 2008, American decided to terminate the Austin and Kansas City service and replace it with service to O'Hare International Airport (which Southwest does not serve) using 50-passenger regional jets in compliance with the Wright provisions regarding aircraft size, although American Eagle later stopped service from Love field altogether.

On June 15, 2006, it was announced that American Airlines, Southwest Airlines, Dallas-Fort Worth International Airport and the cities of Dallas and Fort Worth had all agreed to seek full repeal of the Wright Amendment, with several conditions. Among them: the ban on nonstop flights outside the Wright zone would stay in place until 2014; through-ticketing to domestic airports (connecting flights to long-haul destinations) would be allowed immediately; Love Field's maximum gate capacity would be lowered from 32 to 20 gates; and Love Field would handle only domestic flights non-stop. Southwest will be able to operate from 16 gates, American 2 gates, and Continental 2 gates. JetBlue and Northwest Airlines claimed that the gate cap will effectively ban any airlines not named in the compromise to ever operate from Love Field, even though the agreement calls for Southwest, American and Continental to share gates with new airlines that desire to serve the airport. The cap of 20 gates would effectively restrict the purpose of the 2014 lifting of the ban on nonstop flights outside the Wright zone.

After extensive negotiations with the House and Senate Judiciary Committees, the compromise bill passed both Houses of Congress on Friday, September 29, just before the 109th Congress adjourned for the November elections. Kay Bailey Hutchison led the effort to pass the bill in the Senate while Rep. Kay Granger led a bipartisan Texas House coalition to see the bill through to a successful conclusion in the House. President George W. Bush signed the bill into law on October 13, 2006.[36] Southwest and American Airlines then required approval from the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to begin one-stop flights from Love Field to destinations outside the Wright limits.[37]

On October 17, 2006, Southwest Airlines announced that it would begin one-stop or connecting service between Love Field and 25 destinations outside the Wright zone on October 19, 2006.[38] American Airlines made travel between Love Field and locations outside the Wright zone available by October 18, 2006.[39][40]

In 2008 the airport handled 8,060,792 passengers.[41]

In early 2009 a plan to modernize Love Field was announced. The $519 million master plan will replace the existing terminals with a new 20-gate concourse and expanded baggage facilities.[34] The project also called for a $250 million people mover system to connect to Dallas Area Rapid Transit's Burbank Station,[42] but this was eliminated in favor of a cheaper bus connection to the Inwood Station.[43]

The airport became embroiled in a controversy over concessions contracts when Dallas mayor Tom Leppert, during a March 3, 2010, City Council meeting, abruptly withdrew support for no-bid contracts with current airport food vendor Star Concessions Ltd. and newspaper and book vendor Hudson Retail Dallas, insisting that the contracts should be opened to public bidding instead. At a February 22, 2010, meeting, the City Council recommended that the existing contracts, set to expire in June 2011, be extended until 2026 with an additional three-year option and exclusive rights to 54 percent of vending space in a new terminal scheduled to open in 2014.[44] After several abortive attempts to resolve the issue, the City Council voted on August 18, 2010, to open all concessions space in the new terminal for public bidding; city staff would attempt to reach a deal with Star and Hudson to operate existing concessions space from 2011 to 2014, otherwise it would also be opened for public bidding.[45]

2014 to present

Southwest Airlines added Baltimore, Denver, Las Vegas, Orlando, Washington-Reagan and Chicago on October 13, 2014, the day the repeal went into effect. The first flight to operate outside of the Wright Amendment restricted area was Southwest Airlines flight 1013 to Denver (the flight number of which was named after the date). On November 2, 2014, Southwest added new service to Atlanta, Nashville, Fort Lauderdale, Los Angeles, New York-LaGuardia, Phoenix, San Diego, Orange County (CA) and Tampa.[46] On March 10, 2014, Southwest announced that sometime in 2015, it would add service to Boston, Oakland, Panama City Beach (FL), Portland (OR), San Jose (CA), and Sacramento.[47]

In order to get its merger with US Airways approved by the Department of Justice, American Airlines was forced to give up its 2 gates at Love Field. Delta Air Lines, Southwest Airlines and Virgin America all expressed interest, while the DOJ indicated that a low cost carrier should receive the gates.[48] The former American Airlines gates were ultimately granted to Virgin America on October 13, 2014, thus denying the gates to Delta and Southwest.[49][50] Delta had also attempted to secure an underutilized United Airlines gate, but United assured city officials that its flight schedule would intensify effective January 7, 2015, and that a gate would be shared with Southwest in the interim; this prompted the officials to reject Delta's proposal.[49] On October 8, 2014, it was announced that Delta had reached an agreement to temporarily share one Southwest gate, allowing Delta to continue service to its Atlanta hub; however, the agreement terminated when Southwest began nonstop service to Oakland and San Francisco on January 6, 2015. Although it was initially unclear whether or how Delta would maintain a Love Field presence after that date,[51][52] United Airlines subsequently agreed to share one of its gates with Delta until July 6, 2015.[53] Following the closure of Terminal 1, SeaPort Airlines began sharing a Virgin America gate for its twice-daily Essential Air Service flights to El Dorado (AR).[52]

On Monday, December 8, 2014, city officials announced a plan to add 4,000 parking spaces at Love Field, including the proposed construction of a 5-level parking garage across from Ticket Hall. Despite a 2008 forecast predicting that Love Field would have adequate parking to meet demand through 2018, the airport ran out of parking around midday on Thanksgiving, November 27, 2014, forcing arriving travelers to park off-airport and use other means to reach their flights. The parking shortage is expected to worsen in 2015 as the anticipated number of daily departures increases from 148 to 190.[54]

Dallas Love Field will be one of the first airports in the US to celebrate its 100th Anniversary. The airport is scheduled to do so in September 2017.[55]

On June 10, 2016, a shooting occurred at the airport. A man was throwing large rocks at a car with his girlfriend and kids inside. An officer opened fire and fired nine shots. Everybody in the secure gate area was cleared and are currently waiting to be rescreened by the TSA[56][57]

Facilities and aircraft

Dallas Love Field covers an area of 1,300 acres (530 ha) at an elevation of 487 feet (148 m) above mean sea level. It has three runways:[2]

- Runway 13L/31R: 7,752 by 150 feet (2,363 m × 46 m), Surface: Concrete (Built 1943, Extended 1952[10])

- Runway 13R/31L: 8,800 by 150 feet (2,682 m × 46 m), Surface: Concrete (Built 1965[23])

- Runway 18/36: 6,147 by 150 feet (1,874 m × 46 m), Surface: Asphalt (Built 1943[10])

For the 12-month period ending October 31, 2007, the airport had 247,235 aircraft operations, an average of 677 per day: 39% general aviation, 37% scheduled commercial, 23% air taxi and 1% military. At that time there were 693 aircraft based at this airport: 3% single-engine, 4% multi-engine, 93% jet and 1% helicopter.[2]

The City of Dallas Department of Aviation headquarters is on the grounds of the airport.[58]

Main terminal

Modernization of Love Field's terminals was announced in early 2009. The $519 million master plan replaced the existing terminal buildings with a single new 20-gate concourse.

Southwest has preferential leases to all but two of the gates, Gates 11 and 13, to which Virgin America has preferential leases. A temporary gate-sharing agreement between Southwest and Delta and a similar agreement between United and Southwest ended on January 5 and 6 2015, respectively, to allow expansion of the Southwest and United flight schedules.[52] United and Delta then entered into another agreement, permitting Delta to share one of United's gates until July 6, 2015.[53]

On January 30, 2015, Southwest Airlines announced they had entered into a sub-lease agreement for United's 2 Love Field gates; United ended service to Love Field on March 15, 2015. Southwest has announced additional flights and cities with the two extra gates.[59]

Since August 2015, Delta and Southwest have been fighting a legal battle over if Delta should be allowed to remain at Love Field.[60] Delta has been sharing a Southwest gate, which has allegedly been impeding Southwest from adding more flights from the airport.[61] On January 9, 2016, the court ruled in favor of Delta.[62] Delta is now legally allowed to remain operating from Love Field using a Southwest gate.[63]

Legend terminal

The terminal was built by Legend Airlines and was later used by Legend Airlines and Delta Connection/Atlantic Southeast Airlines. Under the terms of lifting the Wright Amendment, the number of gates at the airport is limited thus effectively precluding use of the terminal for scheduled passenger flights. The gates of the former terminal were demolished and the remaining structure converted into a U.S. Customs and Border Protection facility.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

| Airlines | Destinations |

|---|---|

| Delta Air Lines | Atlanta |

| Delta Connection | Seasonal: Atlanta |

| Southwest Airlines | Albuquerque, Amarillo, Atlanta, Austin, Baltimore, Birmingham (AL), Boston, Burbank,[64] Charleston (SC), Charlotte, Chicago–Midway, Columbus (OH), Denver, Detroit, El Paso, Fort Lauderdale, Houston–Hobby, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Las Vegas, Little Rock, Los Angeles, Lubbock, Memphis, Midland/Odessa, Milwaukee, Nashville, New Orleans, New York–LaGuardia, Oakland, Oklahoma City, Omaha, Orange County, Orlando–MCO, Panama City (FL), Pensacola (begins June 11, 2016), Philadelphia, Phoenix–Sky Harbor, Pittsburgh, Portland (OR), Raleigh/Durham, Sacramento, St. Louis, Salt Lake City, San Antonio, San Diego, San Francisco, San Jose (CA), Seattle/Tacoma, Tampa, Tulsa, Washington–National Seasonal: Fort Myers |

| Virgin America | Las Vegas, Los Angeles, New York–LaGuardia, San Francisco, Washington–National |

Previous airline service

Several airlines have served Love Field in the past including: Air Central, American Airlines, American Freighter, Braniff International Airways, Capital Airlines, Central Airlines, Eastern Air Lines, Legend Airlines, Ozark Air Lines, Saturn Airways, SeaPort Airlines,[65] Slick Airways, Southern Air Transport, Trans-Texas Airways, and United Airlines.

Braniff International was once Love Field's largest carrier. It started flying there in the early 1930s [66] and it relocated most of its flights to DFW when it opened in 1973. Braniff kept flying from Love Field until its collapse in May 1982.

Love Field was the primary hub for the startup airline Legend Airlines. The airline worked its way around the Wright Amendment by flying with 56 seat aircraft even to distant cities like Los Angeles and New York City. It shut down in 2005.

American Airlines relaunched flights to the airport in 2005 to compete with Southwest Airlines and fill in the void left by Legend. It eventually terminated service to the airport and sold its 2 gates to Virgin America in 2014.[67]

Continental Express was the first airline to relaunch flights after DFW opened in 1974. Continental started flying daily ERJ 145's between Love Field and George Bush Intercontinental Airport in 1998.[68] In 2012, Continental and United merged. United kept flying the route to Houston until March 2015.[69] Its 2 gates at the airport have since been leased to Southwest Airlines.[70]

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | City | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Houston–Hobby, Texas | 623,000 | Southwest |

| 2 | Austin, Texas | 377,000 | Southwest, Virgin America |

| 3 | Atlanta, Georgia | 341,000 | Delta, Southwest |

| 4 | Los Angeles, California | 331,000 | Southwest, Virgin America |

| 5 | San Antonio, Texas | 326,000 | Southwest |

| 6 | New York–LaGuardia, New York | 311,000 | Southwest, Virgin America |

| 7 | Chicago–Midway, Illinois | 303,000 | Southwest |

| 8 | New Orleans, Louisiana | 278,000 | Southwest |

| 9 | Washington–National, D.C. | 259,000 | Southwest, Virgin America |

| 10 | Kansas City, Missouri | 249,000 | Southwest |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 7,960,809 | 2000 | 7,077,549 | ||

| 2009 | 7,744,522 | 1999 | 6,820,867 | ||

| 2008 | 8,060,792 | 1998 | 6,715,596 | ||

| 2007 | 7,953,385 | 1997 | 6,807,894 | ||

| 2006 | 6,874,717 | 1996 | 7,064,515 | ||

| 2015 | 14,497,498 | 2005 | 5,909,599 | ||

| 2014 | 9,413,636 | 2004 | 5,889,756 | ||

| 2013 | 8,470,586 | 2003 | 5,588,930 | ||

| 2012 | 8,173,927 | 2002 | 5,622,754 | ||

| 2011 | 7,980,020 | 2001 | 6,685,618 |

Public transit

Currently, DART bus route 524 serves the airport.

The DART Orange Line & Green Line light rail serves the airport at Inwood/Love Field Station, which opened in 2010. Passengers must use the bus from route 524 in order to travel between Love Field and the Inwood/Love Field Station.

Charter Service and FBOs

Love Field is also home to a number of charter flight companies and FBOs including:

- Landmark Aviation

- Business Jet Center (FBO)

- Business Jet Access (Charter)

- Signature Flight Support

- Jet Aviation

Accidents and incidents

- December 23, 1936: A Braniff Airways Lockheed Model 10 Electra airliner, registration number NC-14905, suffered an engine failure during a go-around while conducting a non-scheduled test flight; the pilot tried to turn back towards Love Field but lost control, causing the craft to spin into the northern shore of Bachman Lake. Its six occupants, all Braniff employees, died in the crash and ensuing fire.[75]

- November 29, 1949: American Airlines Flight 157, a Douglas DC-6, was on final approach to Runway 36 when the flight crew lost control, causing the airliner to slide off the runway and strike a parked airplane, a hangar, and a flight school before crashing into a business across the street from the airport. 26 passengers and two flight attendants died in the crash and ensuing fire; the pilot, co-pilot, flight engineer, and 15 others survived.

- June 28, 1952: A Temco Swift private plane collided with American Airlines Flight 910, a Douglas DC-6 on final approach to Love Field from San Francisco, California; the DC-6 landed safely with no injuries to the 55 passengers and five crew. Both occupants of the Swift died on impact with the ground.

- May 15, 1953: A Braniff International Airways Douglas DC-4 carrying 48 passengers and five crew slid off the end of Runway 36, crossed Lemmon Avenue, and plowed into an embankment. Despite reportedly heavy automobile traffic on the busy street, no vehicles were struck, and nobody aboard the airliner was seriously injured. The crash was attributed to poor braking action on the rain-slicked runway.[76]

- July 9, 1953: A Southern Air Transport Curtiss-Wright C-46 Commando cargo transport, carrying a crew of two, skidded off the runway and flipped over after a hard landing. The pilot suffered significant injuries; the co-pilot escaped safely.[77]

- May 14, 1960: The pilot of a Beechcraft Bonanza private plane suffered an apparent heart attack and fell unconscious while en route from Fort Worth to Dallas. The pilot's wife and sole passenger, who was not a trained pilot, managed to guide the Bonanza to Love Field but crashed while attempting to land. Both occupants suffered severe injuries and the pilot was pronounced dead, but it is unclear whether his death resulted from the heart attack or from injuries sustained during the crash.[78][79]

- September 14, 1960: An airline maintenance inspector lost control of a Braniff International Airways Douglas DC-7 during a taxi test and crashed into a hangar at high speed. The inspector died and five of the six mechanics aboard were injured.[80]

- April 18, 1962: A Douglas DC-3 operated by an aviation company affiliated with Purdue University, registration number N3588, crashed immediately after taking off to test a newly installed engine. The craft exploded into flames, killing all three people aboard.[81][82] The crash was attributed to insufficient airspeed at takeoff, and the National Transportation Safety Board noted that the pilot was not properly qualified to fly a DC-3.[83]

- April 19, 1963: A Beechcraft Bonanza private plane crashed short of the runway on final approach, killing both occupants.[84]

- January 29, 1966: A Piper Cherokee Six air taxi, registration number N3246W, suffered an engine failure on final approach to Love Field and struck trees while the pilot was attempting an emergency landing on a nearby street.[85] The pilot and five passengers were injured; the engine failure was attributed to carburetor icing.[86]

- February 10, 1967: A Beechcraft D18S, registration number N7388, crashed at Love Field after a propeller blade separated during takeoff; the pilot and both passengers died.[87]

- September 27, 1967: All seven occupants of an Aero Commander 560E, registration number N3831C, died after the left-hand wing broke during the landing approach, sending the plane plummeting into Mockingbird Lane in Highland Park, Texas. Wreckage tore through the playground of Bradfield Elementary School. The school was not in session and nobody on the ground was seriously harmed.[88]

- September 29, 1970: After a scheduled flight from Denver, Colorado, the landing gear of a Braniff International Airways Boeing 720, registration number N7080, collapsed during landing. The automatic gear extension mechanism had failed in flight and the flight crew manually lowered the gear but neglected to lock it in the "Down" position. The airliner slid to a halt on the runway, suffering significant damage. There were no injuries to the 47 passengers and seven crew.[89][90]

- June 7, 1971: A Dallas Police Department Bell 47G-5 helicopter, registration number N2022W, was destroyed when heavy winds blew the craft into an airfield fence during landing; the observer suffered minor injuries and the pilot escaped safely.[91][92]

- December 26, 1973: The pilot of a Tricon International Airlines Beechcraft C-45H cargo transport, registration number N118X, lost control while circling Love Field for a precautionary landing after being unable to raise the landing gear during takeoff. The C-45 struck two houses southeast of the airport, killing the pilot and injuring a person on the ground. The crash was attributed to insufficient airspeed and improper loading.[93][94]

- April 18, 1975: A Cessna 310F, registration number N5818X, ran off the end of the runway, struck a fence, and burned after losing engine power during takeoff. The craft's two occupants, a student pilot and flight instructor, escaped with minor injuries. The crash was attributed to fuel starvation: the student pilot had mishandled the fuel control valve (known as the fuel selector) and taken off with the fuel tanks disconnected from the engines.[95][96]

- June 8, 1976: The pilot of a Cessna 175, registration number N9259B, executed an emergency landing on nearby Mockingbird Lane soon after takeoff from Love Field, striking a telephone pole and a moving automobile. The aircraft was substantially damaged, but there were no serious injuries to the aircraft's four occupants or to the driver of the car. The crash was attributed to insufficient airspeed and overloading.[97][98]

- January 27, 2000: After its tailplane deicing system failed during the landing approach, a Misubishi MU-300 business jet, registration number N900WJ, touched down on Runway 31R at higher-than-normal speed as recommended for such a situation. When it became evident that the aircraft was going to overrun the runway due to the high speed and poor braking action on the slush-covered pavement, the pilot purposely steered the jet into an embankment to avoid striking light poles past the far end of the runway. There were no injuries to the four passengers or two crew, but the aircraft was written off.[99][100]

See also

References

- Notes

- ^ The crash occurred in the neighborhood northwest of Love Field and southeast of Bachman Lake; many of the buildings and streets in this area were later removed to accommodate Runway 13R/31L.

- Citations

- ^ "Dallas, Texas Love Field Airport". Dallas-lovefield.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b c d FAA Airport Form 5010 for DAL PDF, effective 2008-04-10

- ^ "Dallas, Texas Love Field Airport". Dallas-lovefield.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Location of U.S. Aviation Fields, The New York Times, 21 July 1918

- ^ William R. Evinger: Directory of Military Bases in the U.S., Oryx Press, Phoenix, Ariz., 1991, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d "Records of the Army Air Forces [AAF]". Archives.gov. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Order of Battle of the United States Land Forces in the First World War, Volume 3, Part 3, Center of Military History, United States Army, 1949 (1988 Reprint)

- ^ a b c d Maurer, Maurer. Aviation in the US Army, 1919-1939 (Report). ISBN 0-912799-38-2.

On July 17, 1926,…the Air Corps got two new brigadier generals [promoted from lieutenant colonel, including] William E. Gillmore to be Chief of the Materiel Division to be created at Dayton, Ohio. … Major Schroeder and Lieutenant Macready's altitude work had a direct bearing on air power for it led to superchargers, oxygen systems, and other equipment … The Boeing 299 crashed during testing at Wright Field on October 30, 1935. Aboard were Tower and four men from the Materiel Division-Maj. Ployer P. Hill, Chief of the Flying Branch, pilot; 1st Lt. Donald L. Putt, copilot; John B. Cutting, engineer; and Mark H. Koogler, mechanic. Taking off, the plane climbed steeply to 300 feet, stalled, crashed, and caught fire. Tower and Hill died. Investigation disclosed that no one had unlocked the rudder and elevator controls.

- ^ Payne, Darwin and Kathy Fitzpatrick (1999), From Prairie To Planes, Three Forks Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 5, 2009. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Official Aviation Guide shows (Report). Chicago: Official Aviation Guide Company.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Futrell, Robert F. (July 1947). Development of AAF Base Facilities in the United States: 1939-1945 (Report). Vol. ARS-69: US Air Force Historical Study No 69 (Copy No. 2). Air Historical Office.

The headquarters and the experimental activities of the Material Division, OCAC, were located at Wright Field, Dayton, Ohio, a new field that had been occupied in 1927.22

(p. 7) - ^ [full citation needed]History of the 33d Ferrying Group (AFHRA document) (Report).

- ^ Manning, Thomas A. (2005), History of Air Education and Training Command, 1942–2002. Office of History and Research, Headquarters, AETC, Randolph AFB, Texas ASIN: B000NYX3PC

- ^ Shaw, Frederick J. (2004), Locating Air Force Base Sites History’s Legacy, Air Force History and Museums Program, United States Air Force, Washington D.C., 2004.

- ^ author tbd (9 November 1983). Hellickson, Gene—2007 transcription using Microsoft Word (ed.). Historical Summary: Radar Bomb Scoring, 1945–1983 (PDF) (Report). Office of History, 1st Combat Evaluation Group. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

On 6 June 1945, the 206th Army Air Force Base Unit (RBS) ( 206th AAFBU), was activated at Colorado Springs, Colorado under the command of Colonel Robert W. Burns. He assumed operational control of the two SCR-584 radar detachments located at Kansas City[where?] and Fort Worth [sic] [Det B at Dallas Love Field]… On 24 July 1945, the 206th was redesignated the 63rd AAFBU (RBS) and three weeks later was moved to Mitchell [sic] Field, New York, and placed under the command of the Continental Air Force. [sic] On 5 March 1946, the organization moved back to Colorado Springs[dubious – discuss] and on 8 March of the same year was redesignated the 263rd AAFBU.

{{cite report}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: numeric names: editors list (link) (html transcription available at http://www.1stcombatevaluationgroup.com/aboutus.html ) - ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 5, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Staff writers (1949-11-30). "Worst Plane Crash In Texas History Takes Lives of 28". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Ranter, Harro. "Dallas-Love Field, TX profile - Aviation Safety Network". Aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Official Airline Guide, Washington DC: American Aviation Publications, 1957

- ^ Donald S. Nelson: An Inventory of his Architectural Records, Drawings, and Photographs, 1910-1975

- ^ "A Look Back at Dallas Love Field". Southwest Airlines. January 29, 2010.

- ^ a b Staff writers (1965-04-03). "1st Plane Uses New Runway". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Frank Hildebrand (1961-05-11). "Board Action Asked In Runway Wrangle". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1961-04-04). "Group Challenges Jet Runway Plans". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1961-12-16). "Court Backs Dallas In Runway Hassle". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Ed Cocke (1963-02-02). "Love Field Battle Moves Into Court". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "Braniff "Jet-Rail"". Braniffpages.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Dallas Love Field - 1972". DepartedFlights.com. Retrieved 11 September 2015.

- ^ Jim Ewell and Tom Williams (1972-01-13). "Braniff Hijacker Taken as Police Storm Plane". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Tom Johnson (1972-01-13). ""Keep Him Going," Dispatcher Offers". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Maryln Schwartz (1972-01-14). "Hurst Seen As Dreamer". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Ronald George (1973-02-03). "Hurst Gets 20 Years for Hijacking". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Wright Amendment#Text of amendment

- ^ Bailey, Sen Hutchison, Kay (13 July 2006). "S.3661 - Wright Amendment Reform Act of 2006". Thomas.loc.gov. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Wright repeal has one step left," Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Oct. 14, 2006

- ^ "Wright Amendment Reform Act of 2006 Enacted Into Law; Southwest Airlines Offers Customers $99 One-Way Fares and Increased Travel Options From Dallas Love Field" (Press release). Southwest Airlines. 2006-10-17. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ^ Banstetter, Trebor (2006-10-17). "Love's new menu: 25 new cities". Fort Worth Star-Telegram. Archived from the original on 2006-10-28. Retrieved 2006-10-18.

- ^ "Airline Tickets and Airline Reservations from American Airlines". American Airlines. Retrieved October 18, 2006.

- ^ "Dallas Love Field Total Passengers, December 2008" (PDF). City of Dallas Aviation Department. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 14, 2010. Retrieved November 24, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Hudson, Travis (3 February 2014). "Ask DART: Will Dallas Love Field service change when the Wright Amendment ends?". Dartdallas.dart.org. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Sam Merten (2010-06-17). "The Battle Over Airport Contracts Opens a Rift Between the Mayor and Minority City Council Members". Dallas Observer.

- ^ Rudolph Bush (2010-08-19). "Love Field no-bid concessions contracts defeated at City Hall". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "Investor Relations". Southwest.investorroom.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Investor Relations". Southwest.investorroom.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Andrea Ahles. "U.S. says Delta Air Lines not "appropriate" choice for Love Field gates". Star-telegram.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b Wilonsky, Robert (September 30, 2014). "It's official: City tells a 'disappointed' Delta Air Lines it can no longer fly out of Dallas Love Field". The Dallas Morning News City Hall Blog. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ^ Murray, Lance (September 30, 2014). "Dallas tells Delta Air Lines it can't fly from Love Field after Oct. 13". Dallas Business Journal. Retrieved September 30, 2014.

- ^ Maxon, Terry (October 8, 2014). "Update: Delta Air Lines to stay at Dallas Love Field through end of 2014". The Dallas Morning News Airline Biz Blog. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b c Bachman, Justin (October 8, 2014). "Space Fight: Airlines Let Sharp Elbows Fly in Dallas Airport's Reshuffle". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved October 9, 2014.

- ^ a b Wilonsky, Robert. "Delta Air Lines cuts deal with Dallas, United to remain at Love Field for 180 days". City Hall Blog. The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ^ Stephen, Young (December 8, 2014). "After Thanksgiving Parking Nightmare, Love Field to Add 4,000 Spots". The Dallas Observer Blogs. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ^ TEGNA. "The death of Love Field was greatly exaggerated". Wfaa.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Love Field Shooting Began as Domestic Incident: DPD". Nbcdfw.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Man shot outside baggage claim at Dallas Love Field Airport" (Web). CNN.Com. Turner Broadcasting inc. 10 June 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

An incident at Dallas Love Field Airport that led to a man being shot by police outside the terminal stemmed from a domestic disturbance between a woman and her children's father, a police spokesman said.

- ^ "Aviation Administration." City of Dallas. Retrieved on January 19, 2010. "Dallas Love Field 8008 Cedar Springs Road, LB 16 Dallas, TX 75235-2852"

- ^ "More to Love: Southwest Airlines to Offer More Destinations, More Low Fares for Dallas Customers - Southwest Airlines Newsroom". Swamedia.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Judge To Decide If Delta Airlines Will Continue At Love Field". Dfw.cbslocal.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Maxon, Terry. "FAA steps into Delta-Southwest Airlines fight over Dallas Love Field gates, with warning to city of Dallas". Aviationblog.dallasnews.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Southwest Loses Gate Skirmish With Delta Over Dallas Love Field Slots". Skift.com. 9 January 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "UPDATE 1-Delta granted right to stay at Dallas Love Field - U.S. District Court". Reuters.com. 9 January 2016. Retrieved 10 June 2016 – via Reuters.

- ^ "Southwest Airlines to offer nonstop service between Burbank, Dallas Love Field". Dailynews.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Maxon, Terry. "Dallas Love Field to lose service from one airline (the smallest one)". Aviationblog.dallasnews.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "The Braniff Pages - Tom Braniff Years". Braniffpages.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "It's official: Virgin America to get Dallas Love gates". Usatoday.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Dallas, Texas Love Field Airport". Dallas-lovefield.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Maxon, Terry. "Analyst criticizes United Airlines for boosting Dallas Love Field flights". Aviationblog.dallasnews.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "Southwest Airlines gaining two Dallas Love Field gates". Dallasnews.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ "RITA - BTS - Transtats". Transtats.bts.gov. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b Historical Data. Retrieved on Mar 25, 2015.

- ^ a b "Dallas, Texas Love Field Airport". Dallas-lovefield.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Dallas, Texas Love Field Airport". Dallas-lovefield.com. Retrieved 10 June 2016.

- ^ Staff writers (1942-10-17). "Braniff Airways Plane Crashes, Burning Six to Death; Ship Falls on Shore of Bachman's Lake as Motors Fail". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1953-05-16). "Passenger Plane Overshoots Field". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Roy Johnson (1953-07-10). "C-46 Crash Traps Pilot at Airport". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1960-05-15). "Light Plane Falls; Dallas Oilman Dies". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Julian Levine (1960-05-17). "A Plane Crashed; A Drama Ended". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1960-09-15). "Taxiing Airliner Strikes Building, Kills Inspector". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1962-04-19). "2 Killed in Love Field Air Crash". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1962-04-20). "Burns Fatal to Victim of Crash". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW62A0028". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ Staff writers (1963-04-20). "Crash Kills 2 at Love Field". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Peter Brown (1966-01-30). "Plane Falls on Street; Six Injured". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW66A0067". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-06-09.

- ^ James Ewell and David Morgan (1967-02-11). "3 Die in Love Field Crash". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ James Ewell and John Geddie (1960-09-28). "Private Plane Plunges Full-Speed into Mockingbird Lane, Killing 7". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ Staff writers (1970-09-30). "Jet LAnds Safely After Wheel Collapse". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW71AF015". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-07-14.

- ^ Staff writers (1971-06-08). "Dallas Police Helicopter Crashes at Love Field". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW71FPA32". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ^ James Ewell and Don Mason (1973-12-27). "Fiery Crash Kills Pilot". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW74AF047". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW75FPA24". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ Staff writers (1975-04-19). "Two Escape Flames When Aircraft Burns". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Report FTW76FPA24". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-09-04.

- ^ Dan Watson (1976-06-09). "Plane crash-lands safely on city lane". The Dallas Morning News.

- ^ "NTSB Probable Cause Report FTW00LA084". National Transportation Safety Board. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

- ^ "ASN Accident Description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 2009-09-24.

External links

- Dallas Love Field (official site)

- DFW Tower.com

- Friends of Love Field

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective November 28, 2024

- 1917 establishments in Texas

- Airfields of the United States Army Air Forces in Texas

- Airports in Dallas, Texas

- Airports established in 1917

- Buildings and structures associated with the assassination of John F. Kennedy

- Transportation in Dallas County, Texas

- World War I airfields

- World War I sites in the United States

- Strategic Air Command radar stations

- United States automatic tracking radar stations

- USAAF Contract Flying School Airfields