Executive Order 13769: Difference between revisions

Ellenor2000 (talk | contribs) m →Reactions: KKK name correction |

|||

| Line 110: | Line 110: | ||

=== Dual citizens === |

=== Dual citizens === |

||

There was similar confusion about whether the order affected dual citizens of a banned country and a non-banned country. The State Department said that the order did not affect U.S. citizens who also hold citizenship of one of the seven banned countries.<ref name=cnn_dual>{{cite news |last=Merica |first=Dan |url=http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/29/politics/donald-trump-travel-ban-green-card-dual-citizens/ |title=How Trump's travel ban affects green card holders and dual citizens - CNNPolitics.com |publisher=Cnn.com |date= |accessdate=January 30, 2017}}</ref> On January 28, the State Department stated that other travelers with dual nationality of one of these countries—for example, an Iranian who also holds a Canadian passport—would not be permitted to enter.<ref name=cnn_dual/> However, the [[International Air Transport Association]] told their airlines that dual nationals who hold a passport from a non-banned country would be allowed in.<ref name=cnn_dual/> The [[United Kingdom]]'s [[Foreign and Commonwealth Office]] also issued a press release saying that |

There was similar confusion about whether the order affected dual citizens of a banned country and a non-banned country. The State Department said that the order did not affect U.S. citizens who also hold citizenship of one of the seven banned countries.<ref name=cnn_dual>{{cite news |last=Merica |first=Dan |url=http://www.cnn.com/2017/01/29/politics/donald-trump-travel-ban-green-card-dual-citizens/ |title=How Trump's travel ban affects green card holders and dual citizens - CNNPolitics.com |publisher=Cnn.com |date= |accessdate=January 30, 2017}}</ref> On January 28, the State Department stated that other travelers with dual nationality of one of these countries—for example, an Iranian who also holds a Canadian passport—would not be permitted to enter.<ref name=cnn_dual/> However, the [[International Air Transport Association]] told their airlines that dual nationals who hold a passport from a non-banned country would be allowed in.<ref name=cnn_dual/> The [[United Kingdom]]'s [[Foreign and Commonwealth Office]] also issued a press release saying that the restrictions apply to those traveling from the listed countries, not those that merely have their citizenship.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.gov.uk/government/news/presidential-executive-order-on-inbound-migration-to-us |title=Presidential executive order on inbound migration to US |date=January 29, 2017 |publisher=[[Foreign and Commonwealth Office]] |archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20170129211109/https://www.gov.uk/government/news/presidential-executive-order-on-inbound-migration-to-us |archivedate=January 29, 2017}}</ref> The confusion led companies and institutions to take a more cautious approach; for example, [[Google]] told its dual-national employees to stay in the United States until more clarity could be provided.<ref name=cnn_dual/> |

||

===Deleted provision regarding safe zones in Syria=== |

===Deleted provision regarding safe zones in Syria=== |

||

Revision as of 21:19, 9 February 2017

| Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States | |

| |

U.S. President Donald Trump signing the order at the Pentagon, with Vice President Mike Pence (left) and Secretary of Defense James Mattis (right) at his side. | |

Executive Order 13769 in the Federal Register | |

| Other short titles | 'Travel ban' |

|---|---|

| Type | Executive order |

| Executive Order number | 13769 |

| Signed by | Donald Trump on January 27, 2017 |

| Federal Register details | |

| Federal Register document number | 2017-2281 |

| Publication date | 1 February 2017 |

| Document citation | 82 FR 8977 |

| Summary | |

| |

Executive Order 13769,[1] titled "Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States", is an executive order signed by U.S. President Donald Trump on January 27, 2017. In response to a temporary restraining order (TRO) issued in the case of State of Washington v. Trump, the Department of Homeland Security said on February 4 that it had stopped enforcing the portions of the executive order affected by the judgment, while the State Department activated visas that had been previously suspended. The TRO is currently being appealed.

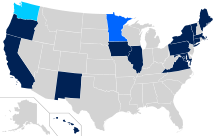

The order limited the number of refugee arrivals to the U.S. to 50,000 for 2017 and suspended the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) for 120 days, after which the program would be conditionally resumed for individual countries while prioritizing refugee claims from persecuted minority religions. The order also indefinitely suspended the entry of Syrian refugees. Further, the order suspended the entry of alien nationals from seven Muslim-majority countries — Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria and Yemen — for 90 days, after which an updated list will be made. The order allows exceptions to these suspensions on a case-by-case basis. The Department of Homeland Security later exempted U.S. lawful permanent residents (green-card holders).

Over a hundred travelers were detained and held for hours without access to family or legal assistance. In addition, up to 60,000 visas were "provisionally revoked", according to the State Department. Within days nearly 50 lawsuits were filed arguing that the order, or actions taken pursuant to the order, violated the U.S. Constitution, federal statutes, and treaty obligations. Federal courts issued emergency orders halting detention, expulsion, or blocking of lawful travelers, pending final rulings.

Domestically, the order was criticized by Democratic and Republican members of Congress, universities, business leaders, Catholic bishops, and Jewish organizations. A record 1,000 U.S. diplomats signed a dissent cable opposing the order. Public opinion was divided, with initial national polls yielding inconsistent results. Protests against the order erupted in airports and cities. Internationally, the order prompted broad condemnation, including from longstanding U.S. allies. The travel ban and suspension of refugee admissions was criticized by top United Nations officials and by a group of 40 Nobel laureates and thousands of other academics.

Background

Restrictions by previous administration

Between 2015 and 2016, the seven countries listed in the executive order were placed on the list of "countries of special concern" by the Obama administration.[2] The executive order refers to these countries as "countries designated pursuant to Division O, Title II, Section 203 of the 2016 consolidated Appropriations Act."[3] Additionally, in 2011, additional background checks were imposed on the nationals of Iraq.[4]

Trump's press secretary Sean Spicer has cited these restrictions as evidence that the executive order is merely an expansion of the previous administration's policies.[citation needed] However, according to the fact-checkers at Politifact, New York Times and Washington Post, Obama's restrictions cannot be compared to this executive order because they were in response to a credible threat, and were not a blanket ban on all individuals from those countries; these fact-checking articles concluded that the Trump administration's claims about the Obama administration were misleading and false.[3][5][6]

Donald Trump's statements during the presidential campaign

Donald Trump became the U.S. president on January 20, 2017. He has long said, without presenting evidence, that terrorists are using the U.S. refugee resettlement program to enter the country.[9] As a candidate, Trump's "Contract with the American Voter" pledged to suspend immigration from "terror-prone regions".[10][11] Trump-administration officials then billed the executive order as fulfilling this campaign promise.[12]

During his initial election campaign, Trump had proposed a temporary, conditional, and "total and complete" ban on Muslims entering the United States.[9][13][14][15] His proposal was met by opposition by U.S. politicians.[13] Mike Pence and James Mattis were among those who opposed the proposal.[13][16] On June 12, in reference to the 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting that occurred on the same date, Trump, via Twitter, renewed his call for a Muslim immigration ban.[17][18] On June 13, Trump proposed to suspend immigration from "areas of the world" with a history of terrorism, a change from his previous proposal to suspend Muslim immigration to the U.S; the campaign did not announce the details of the plan at the time, but Jeff Sessions, an advisor to Trump campaign on immigration,[19] said the proposal was a statement of purpose to be supplied with details in subsequent months.[20] In a speech on August 31, 2016, Trump vowed to "suspend the issuance of visas" to "places like Syria and Libya."[21][22]

President Trump told the Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN) that Christian refugees would be given priority in terms of refugee status in the United States,[23] after saying that Syrian Christians were "horribly treated" by his predecessor, Barack Obama.[24][25] Christians make up very small fractions (0.1% to 1.5%) of the Syrian refugees who have registered with the UN High Commission for Refugees in Syria, Jordan, Iraq, and Lebanon; those registered represent the pool from which the U.S. selects refugees.[26] António Guterres, then the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, said in October 2015 that many Syrian Christians have ties to the Christian community in Lebanon and have sought the UN's services in smaller numbers.[26] During 2016, the U.S. had admitted almost as many Christian as Muslim refugees.[25] Based on this data, Senator Chris Coons accused Trump of spreading "false facts" and "alternative facts."[27]

A 2015 report published by the Migration Policy Institute found that 784,000 refugees had resettled in the United States since September 11, 2001, with only 3 arrested for suspected terrorism.[28] In January 2016, the Department of Justice (DOJ), upon request by the Senate Subcommittee on Immigration and the National Interest, provided a list of 580 public international terrorism and terrorism-related convictions from September 11, 2001, through the end of 2014.[29] Based on this data and news reports and other open-source information, the committee determined that at least 380 among the 580 convicted were foreign-born.[30] The Cato Institute's Alex Nowrasteh said that the list of 580 convictions shared by DOJ was problematic in that "241 of the 580 convictions, or 42 percent, were not even for terrorism offenses"; they started with a terrorism tip but ended up with a non-terrorism charge, like "receiving stolen cereal."[31][32][33][34]

Development of the order

The New York Times observed that candidate Trump in his June 13, 2016, speech was reading from statutory language to justify the President's authority to suspend immigration from areas of the world with a history of terrorism.[35] The Washington Post identified the referenced statute as 8 U.S.C. 1182(f).[36] This was the statutory subsection eventually cited in sections 3, 5, and 6 of the executive order.[37]

According to CNN, the executive order was developed primarily by White House officials (which the Los Angeles Times reported as including "major architect" Stephen Miller and Steve Bannon[38]) without input from the U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) that is typically a part of the drafting process.[39] This was disputed by White House officials.[39] The OLC usually reviews all executive orders with respect to form and legality before issuance. The White House under previous administrations, including the Obama administration, has bypassed or overruled the OLC on sensitive matters of national security.[40]

Trump aides said that the order had been issued in consultation with Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and State Department officials.[41] Officials at the State Department and other agencies said it was not.[41][42] An official from the Trump administration said that parts of the order had been developed in the transition period between Trump's election and his inauguration.[43] On January 29, NBC News reported that the order was not reviewed by the Justice Department, DHS or by the departments of State or Defense, and that attorneys at the National Security Council were blocked from evaluating the order[citation needed]. However, CNN reported that Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly and Department of Homeland Security leadership saw the final details shortly before the order was finalized.[44] On January 31, John Kelly told reporters that he "did know it was under development" and had seen at least two drafts of the order.[45] For the Department of Defense, James Mattis did not see a final version of the order until the morning of the day President Trump signed it (the signing occurred shortly after Mattis' swearing-in ceremony for Secretary of Defense in the afternoon[46][47]), and the White House did not offer Mattis the chance to provide input while the order was drafted.[48]

Rudy Giuliani said on Fox News that President Trump came to him for guidance over the order.[49] He said that Trump called him about a "Muslim ban" and asked Giuliani to form a committee to show him "the right way to do it legally".[50][51] The committee, which included former U.S. Attorney General and Chief Judge of the Southern District of New York Michael Mukasey, and Reps. Mike McCaul and Peter T. King, decided to drop the religious basis and instead focus on regions where, as Giuliani put it, there is "substantial evidence that people are sending terrorists" to the United States.[51]

Provisions

Section 1, describing the purpose of the order, invoked the September 11 attacks, stating that then State Department policy prevented consular officers from properly scrutinizing the visa applications of the attackers.[52][53][54] However, none of the September 11 hijackers were from any of the seven banned countries.[53][55] When announcing his executive action, Trump made similar references to the attacks several times.[55]

The seven countries targeted by the executive order exclude Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and other Muslim-majority countries where The Trump Organization has conducted business or pursued business opportunities.[56][57] Legal scholar David G. Post, through an opinion column in the Washington Post, initially suggested that Trump had "allowed business interests to interfere with his public policy making" and called for Trump's impeachment. However, he later modified that call to instead ask for Trump's financial information.[58]

Visitors, immigrants and refugees

Section 3 of the order blocks entry of aliens from Libya, Sudan, Somalia, Syria, Iran, Iraq, and Yemen, for at least 90 days regardless of whether or not they have a valid non-diplomatic visa.[59][60][61] This order affects about 218 million people who are citizens of these countries.[62] After 90 days a list of additional countries—not just those listed in[a] of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA)—must be prepared.[63][64] The cited section of the INA refers to aliens who have been present in or are nationals of Iraq, Syria, and other countries designated by the Secretary of State.[65] Citing Section 3(c) of the Executive Order, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for Consular Affairs Edward J. Ramotowski issued a notice that "provisionally revoke[s] all valid nonimmigrant and immigrant visas of nationals" of the designated countries.[66][67][68]

The Secretary of Homeland Security, in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Director of National Intelligence, must conduct a review to determine the information needed from any country to adjudicate any visa, admission, or other benefit under the INA. Within 30 days, the Secretary of Homeland Security must list countries that do not provide adequate information.[69] The foreign governments then have 60 days to provide the information on their nationals, after which the Secretary of Homeland Security must submit to the President a list of countries recommended for inclusion on a Presidential proclamation that would prohibit the entry of foreign nationals from countries that do not provide the information.[64]

Section 5 suspends the U. S. Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) for at least 120 days but stipulates that the program can be resumed for citizens of the specified countries if the Secretary of State, Secretary of Homeland Security and the Director of National Intelligence agree to do so.[59][64] The suspension for Syrian refugees is indefinite.[59][69][70] The number of new refugees allowed in 2017 is capped to 50,000, down from 110,000.[71] After the resumption of USRAP, refugee applications will be prioritized based on religion-based persecutions only in the case that the religion of the individual is a minority religion in that country.[72][73][74]

The order said that the Secretaries of State and Homeland Security may, on a case-by-case basis and when in the national interest, issue visas or other immigration benefits to nationals of countries for which visas and benefits are otherwise blocked.[60][69][75][76] Another provision calls for an expedited completion and implementation of a biometric entry/exit tracking system for all travelers coming into the United States, regardless of whether they are foreigners or not.[69][77]

Secretary of Homeland Security, John Kelly has stated to congress that the department is considering a requirement that refugees and visa applicants reveal social media passwords as part of security screening. The idea was one of many to strengthen border security, as well as requesting financial records.[78] The Obama administration released a memo in 2011 revealing a plan to vet social media accounts for visa applicants.[79] John Kelly has stated that the temporary ban is important, and that the DHS is developing what "extreme vetting" might look like.[80]

Green-card holders

There was some confusion about the status of green card holders (i.e., lawful permanent residents). Initially, the Department of Homeland Security said that the order barred green-card holders from the affected countries, and White House officials said that they would need a case-by-case waiver to return.[81] On January 29, White House Chief of Staff Reince Priebus said that green-card holders would not be prevented from returning to the United States.[82] According to the Associated Press, as of January 28, no green-card holders were ultimately denied entry to the U.S., although several initially spent "long hours" in detention.[82][83] On January 29, the Secretary of Homeland Security John F. Kelly deemed entry of lawful permanent residents into the U.S. to be "in the national interest", exempting them from the ban according to the provisions of the executive order.[82][84] On February 1, White House Counsel Don McGahn issued a memorandum to the heads of the departments of State, Justice, and Homeland Security clarifying that the ban-provisions of the executive order do not apply to lawful permanent residents.[85][86]

Dual citizens

There was similar confusion about whether the order affected dual citizens of a banned country and a non-banned country. The State Department said that the order did not affect U.S. citizens who also hold citizenship of one of the seven banned countries.[87] On January 28, the State Department stated that other travelers with dual nationality of one of these countries—for example, an Iranian who also holds a Canadian passport—would not be permitted to enter.[87] However, the International Air Transport Association told their airlines that dual nationals who hold a passport from a non-banned country would be allowed in.[87] The United Kingdom's Foreign and Commonwealth Office also issued a press release saying that the restrictions apply to those traveling from the listed countries, not those that merely have their citizenship.[88] The confusion led companies and institutions to take a more cautious approach; for example, Google told its dual-national employees to stay in the United States until more clarity could be provided.[87]

Deleted provision regarding safe zones in Syria

A prior draft of the order (leaked to a human rights organization[which?] before the order went into effect[89]) would have ordered that "the Secretary of State, in conjunction with the Secretary of Defense, is directed within 90 days of the date of this order to produce a plan to provide safe areas in Syria and in the surrounding region in which Syrian nationals displaced from their homeland can await firm settlement, such as repatriation or potential third-country resettlement."[90] This provision was not in the final order.[1] Rex Tillerson, Trump's Secretary of State, had not yet taken office at the time the executive order went into effect.[91]

During and after his campaign, Trump proposed establishing safe zones in Syria as an alternative to Syrian refugees’ immigration to the U.S. In the past "Safe Zones" have been interpreted as establishing, among other things, no-fly zones over Syria. During the Obama administration, Turkey encouraged the U.S. to establish Safe Zones; the Obama administration was concerned about the potential for pulling the U.S. into a war with Russia.[92]

On January 30, Saudi Arabia told Trump it supported the creation of safe zones in Syria and Yemen.[93] Two days later, on February 2, Trump discussed safe zones with the government of Jordan.[94] On February 3, the U.S. secured Lebanon's backing for Safe Zones in Syria.[95] On February 1, Russia asked the U.S. to be more specific on its safe-zone plan and expressed hope the U.S. would discuss it with Russia before implementation.[96] On February 3, the United Nations High Commissioner on Refugees opposed safe zones.[97]

Impact

Implementation at airports

Shortly after the enactment of the executive order at 4:42 pm on January 27, border officials across the country began enforcing the new rules. The New York Times reported people with various backgrounds and statuses being denied entry or sent back, including refugees and minority Christians from the affected countries as well as students and green-card holders returning to the United States after visits abroad.[81][98]

People from the countries mentioned in the order with valid visas were turned away from flights to the U.S.[99] Some were stranded in a foreign country while in transit.[100] Several people already on planes flying to the U.S. at the time the order was signed were detained on arrival.[99] On January 28, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) estimated that there were 100 to 200 people being detained in U.S. airports,[101] and hundreds were barred from boarding U.S.-bound flights.[102] About 60 legal permanent residents were reported as detained at Dulles International Airport near Washington, D.C.[103] Travelers were also detained at O'Hare International Airport without access to their cellphones and unable to access legal assistance.[104] The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) said that on January 28, the order was applied to "less than one percent" of the 325,000 air travelers who arrived in the United States.[105] By January 29, DHS estimated that 375 travelers had been affected with 109 travelers in transit and another 173 prevented from boarding flights.[106] In some airports, there were reports that Border Patrol agents were requesting access to travelers' social media accounts.[107]

On February 3, 2017, attorneys for the DOJ's Office of Immigration Litigation advised a judge hearing one of the legal challenges to the order that more than 100,000 visas have been revoked as a consequence of the order. They also advised the judge that no legal permanent residents have been denied entry.[108] The State Department later revised this figure downward to fewer than 60,000 revoked visas and clarified that the larger DOJ figure incorrectly included visas that were exempted from the travel ban (such as diplomatic visas) and expired visas.[109][110]

Debate over the numbers of affected persons

On January 30, Trump said in a Twitter post that "Only 109 people out of 325,000 were detained and held for questioning."[111] On January 31, The New York times initially compared the 109 number to 721 people, which Customs and Border Protection reported as the total number of people detained or denied boarding after the ban enforcment. The news outlet later issued a correction to note this.[112] CBP also reported 1,060 waivers for green-card holders had been processed; 75 waivers had been granted for persons with immigrant and nonimmigrant visas; and 872 waivers for refugees had been granted.[113]

The Washington Post fact-checker compared the 109 number quoted by Trump to 90,000, which is the number of U.S. visas issued in the seven affected countries in fiscal year 2015.[114] It later edited the story and faulted the White House for using the overall daily number of travelers as a comparison.[111] The New York Times cited figures of 86,000 visitors, students and workers in addition to 52,365 who passed the requirements for green cards.[115]

Impact on U.S. companies

Google called its traveling employees back to the U.S., in case the order prevents them from returning. About 100 of the company's employees were thought to be affected by the order. Google CEO Sundar Pichai wrote in a letter to his staff that "it's painful to see the personal cost of this executive order on our colleagues. We've always made our view on immigration issues known publicly and will continue to do so."[116][117] Amazon.com Inc., citing disruption in travel for its employees, and Expedia Inc., citing impact to its customers and refund costs, filed declarations in support of the states of Washington and Minnesota in their case against the executive order, State of Washington v. Trump.[118][119]

However, Committee for Economic Development CEO Steve Odland[120], and several other executives & analysts commented that the order won't lead to significant changes in IT hiring practices among US companies since the countries affected are not the primary source of foreign talent.[121] According to the Hill, "a cross-section of legal experts and travel advocates" say that the order "could have a chilling effect on U.S. tourism, global business and enrollment in American universities".[122][123][124]

Other

According to Trita Parsi, the president of the National Iranian American Council, the order distressed citizens of the affected countries, including those holding valid green cards and visas. Those outside the U.S. fear that they will not be allowed in, while those already in the country fear that they will not be able to leave, even temporarily, because they would not be able to return.[125]

The executive order is likely to contribute to a doctor shortage in the United States, disproportionately affecting rural areas and underprovided specialties.[126] According to an analysis by a Harvard Medical School group of professors, research analysts and physicians, the executive order is likely to reduce the number of physicians in the United States, as approximately 5% of the foreign-trained physicians in the United States were trained in the seven countries targeted by the executive order.[127] These doctors are disproportionately likely to practice medicine in rural, underserved regions and specialties facing a large shortage of practitioners.[127] According to The Medicus Firm, which recruits doctors for hard-to-fill jobs, Trump's executive order covers more than 15,000 physicians in the United States.[126]

Reactions

Trump faced much criticism for the executive order. Democrats "were nearly united in their condemnation" of the policy,[128] with opposition from Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer,[129] Senators Bernie Sanders[130] and Kamala Harris,[131] former U.S. Secretaries of State Madeleine Albright[129] and Hillary Clinton,[132] and former President Barack Obama.[133] Among Republicans, some praised the order, with Speaker of the House Paul Ryan saying that Trump was "right to make sure we are doing everything possible to know exactly who is entering our country" while noting that he supported the refugee resettlement program.[134] However, some top Republicans in Congress criticized the order.[128] In a statement, Senators John McCain and Lindsey Graham cited the confusion that the order caused and the fact that the "order went into effect with little to no consultation with the Departments of State, Defense, Justice, and Homeland Security".[135] Senator Susan Collins also objected to the ban.[136] Some 1,000 career U.S. diplomats signed a "dissent cable" (memorandum) outlining their disagreement with the order, sending it through the State Department's Dissent Channel,[137][138][139] a record number.[140] Over 40 Nobel laureates, among many academics, also opposed the order.[141] Polls of the American public's opinion of the order are mixed, with some polls showing majority opposition while others show majority support. Public responses often depended on the wording of polling questions.[142][143] For example, according to two separate Gallup and Reuters–Ipsos polls, about 40% of Americans supported the order and another approximately 50% opposed it; however, a Rasmussen Report poll found that 57% supported the order and 33% opposed it.[142]

The order prompted broad condemnation from the international community, including longstanding U.S. allies[144][145][146] and the United Nations.[147][148] Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stated Canada would continue to welcome refugees regardless of their faith.[149] British Prime Minister Theresa May was initially reluctant to condemn the policy, having just met with Trump the day prior, saying that "the United States is responsible for the United States policy on refugees",[150][151][152] but said she "did not agree" with the approach.[153] France and Germany condemned the order.[144][154] Some media outlets said Australian prime minister Malcolm Turnbull avoided public comment on the order, with Turnbull saying it "is not my job" to criticize it.[155] However, Australian opinion soured after a tweet by Trump appeared to question a refugee deal already agreed by Turnbull and Obama.[156] Iran's Ministry of Foreign Affairs characterized Trump's order as insulting to the Islamic world and counter-productive in the attempt to combat extremism.[157][158] Commander of the Iraqi Air Force said he is "worried and surprised", as the ban may affect Iraqi security forces members (such as Iraqi pilots being trained in US) who are on the front-lines of fighting ISIL terrorism. But traditional US allies in the region were largely silent.[159] On February 1, the United Arab Emirates became the first Muslim-majority nation to back the order.[160][161]

The Catholic Church has condemned the ban and encouraged mercy and compassion towards refugees.[162][163][164] The executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, Amanda Tyler, stated that the executive order was "a back-door bar on Muslim refugees."[165] The director of the Alliance of Baptists, Paula Clayton Dempsey, urged the support of American resettlement of refugees.[165] However, members of the Southern Baptist Convention were largely supportive of the executive order.[165] The Economist noted that that the order was signed on International Holocaust Remembrance Day.[24] This fact, as well as Trump's omission of any reference to Jews or Anti-Semitism in his concurrent address for Holocaust Remembrance Day[166] and the ban's possible effect on Muslim refugees, led to condemnation from Jewish organizations, including the Anti-Defamation League, the HIAS, and J Street,[167] as well as Holocaust survivors.[168]

Some "alt-right" groups, including white nationalists, anti-Semites, conspiracy theorists and the Ku Klux Klan praised the executive order.[169][170] Some European far-right groups and politicians, such as French presidential candidate Marine Le Pen, also applauded the executive order.[171][172][173]

Jihadist and Islamic terrorist groups celebrated the executive order as a victory, saying that "the new policy validates their claim that the United States is at war with Islam."[174] ISIS-linked social media postings "compared the executive order to the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003, which Islamic militant leaders at the time hailed as a 'blessed invasion' that ignited anti-Western fervor across the Islamic world."[174]

Protests at airports

On January 28 and thereafter, thousands of protesters gathered at airports and other locations throughout the United States to protest the signing of the order and detention of the foreign nationals. Members of the United States Congress, including Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Congressman John Lewis (D-GA) joined the protests in their own home states.[175] Google co-founder Sergey Brin and Y Combinator president Sam Altman joined the protest at San Francisco airport.[176][177] Virginia governor, Terry McAuliffe, joined the protest at Dulles International Airport on Saturday.[178]

Legal challenges

Legal challenges to the order were brought almost immediately after its issuance. From January 28 to January 31, almost 50 cases were filed in federal courts. The courts, in turn, granted temporary relief, including a nationwide temporary restraining order (TRO) that bars the enforcement of major parts of the executive order. The TRO specifically blocks the executive branch from enforcing provisions of the executive order that (1) suspend entry into the U.S. for people from seven countries for 90 days and (2) place limitations on the acceptance of refugees, including "any action that prioritizes the refugee claims of certain religious minorities."[179] The TRO also allows "people from the seven countries who had been authorized to travel, along with vetted refugees from all nations, to enter the country."[179] The Trump administration is appealing the TRO.[179]

The plaintiffs challenging the order argue that it contravenes the United States Constitution, federal statutes, or both. The parties challenging the executive order include both private individuals (some of whom were blocked from entering the U.S. or detained following the executive order's issuance) and the states of Washington and Minnesota, represented by their state attorneys general. Other organizations, such as the ACLU, challenged the order in court as well. Additionally, fifteen Democratic state attorneys general released a joint statement calling the executive order "unconstitutional, un-American and unlawful", and that "[w]e'll work together to fight it".[180][181]

In response to the lawsuits, the Department of Homeland Security issued a statement on January 29 saying that that it would continue to enforce all of the executive order and that "prohibited travel will remain prohibited". On the same day, a White House spokesperson said that the rulings did not undercut the executive order. On January 30, Acting Attorney General Sally Yates, an Obama administration appointee holding the position temporarily while a Trump nominee is confirmed, barred the Justice Department from defending the executive order in court, saying the order's effects, which she felt were not in keeping "with this institution's solemn obligation to always seek justice and stand for what is right".[182] After Yates spoke against Trump's refugee ban, however, Trump quickly relieved her of her duties, calling her statement a "betrayal" to the administration. He replaced her with Dana J. Boente, the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia. This leadership alteration was called the Monday Night Massacre.[183][184][185][186]

The state of Washington filed a legal challenge, State of Washington v. Trump, against the executive order;[118][187] Minnesota later joined the case.[188] On February 3, District Judge James Robart in the United States District Court for the Western District of Washington issued a ruling temporarily blocking major portions of the executive order; he said that the plaintiffs had "demonstrate[d] immediate and irreparable injury," and were likely to succeed in their challenge to the federal defendants. Robart explicitly wrote his judgement to apply nationwide. In response to Robart's ruling, the Department of Homeland Security said on February 4 that it had stopped enforcing the executive order, while the State Department reinstated visas that had been previously suspended.[189] On February 3, the Justice Department asked for an emergency stay to reverse Judge Robart's ruling temporarily blocking the executive order nationwide. The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit denied Trump's immediate petition to stay the temporary restraining order from the Federal District Court in Washington State.[190]

See also

Notes

References

- ^ a b 82 FR 8977

- ^ Shelbourne, Mallory (January 29, 2017). "Spicer: Obama administration originally flagged 7 countries in Trump's order". The Hill. News Corp. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Qiu, Linda (January 30, 2017). Sharockman, Aaron (ed.). "Why comparing Trump's and Obama's immigration restrictions is flawed". Politifact. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Arango, Tim (July 12, 2011). "Visa Delays Put Iraqis Who Aided U.S. in Fear". The New York Times. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Park, Haeyoun; Yourish, Karen; Gardiner, Harris (February 6, 2017). "In One Facebook Post, Three Misleading Statements by President Trump About His Immigration Order". The New York Times. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn (February 7, 2017). "Trump's claim that Obama first 'identified' the 7 countries in his travel ban". The Washington Post. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ a b "Report of the Visa Office 2016". Bureau of Consular Affairs, U.S. Department of State. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Arrivals by State and Nationality as of January 31, 2017 (Microsoft Excel), US Department of State, January 31, 2017

- ^ a b Greenwood, Max (January 28, 2017). "ACLU sues White House over immigration ban". The Hill. News Corp. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Trump, Donald (October 23, 2016). "Donald Trump's Contract with the American Voter" (PDF). DonaldJTrump.com. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

my administration will immediately pursue the following ... actions to restore security ... suspend immigration from terror-prone regions where vetting cannot safely occur.

- ^ Bush, Daniel (November 10, 2016). "Read President-elect Donald Trump's plan for his first 100 days". PBS Newshour. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Boyer, Dave (January 25, 2017). "Trump executive order to stem refugees from 'terror-prone' regions". Washington Times. Washington, D.C. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ a b c "Pence once called Trump's Muslim ban 'unconstitutional.' He now applauds a ban on refugees". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ "Trump expected to order temporary ban on refugees". Reuters. January 25, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Donald J. Trump (December 7, 2015). Presidential Candidate Donald Trump Rally (Online Video). Mount Pleasant, South Carolina: C-SPAN. Event occurs at 30:30. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

[I am] calling for a total and complete shutdown of Muslims entering the United States until our country's representatives can figure out what the hell is going on.

- ^ Bender, Bryan; Andrew, Hanna (December 1, 2016). "Trump picks General 'Mad Dog' Mattis as defense secretary". Politico. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ "Trump renews call for Muslim ban in wake of Orlando attack, challenges Clinton to say 'radical Islamic terrorism'". Business Insider. June 12, 2016.

- ^ @@realDonaldTrump (June 12, 2016). "What has happened in Orlando is just the beginning. Our leadership is weak and ineffective. I called it and asked for the ban. Must be tough" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- ^ "DONALD TRUMP RELEASES IMMIGRATION REFORM PLAN DESIGNED TO GET AMERICANS BACK TO WORK". DonaldJTrump.com. August 16, 2016. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved February 4, 2017 – via Breitbart.

The ["detailed policy position"/"immigration reform plan"], which was clearly influenced by Sen. Jeff Sessions who Trump consulted to help with immigration policy ...

- ^ Preston, Julia (June 18, 2016). "Many What-Ifs in Donald Trump's Plan for Migrants". New York Times. Retrieved February 1, 2016.

- ^ Trump, Donald (August 31, 2016). Presidential Candidate Donald Trump Remarks on Immigration Policy (Speech). C-SPAN. Event occurs at 56:42.

- ^ Stephenson, Emily (August 31, 2016). "Trump returns to hardline position on illegal immigration". Phoenix: YahooNews – via Reuters.

- ^ Brody, David (January 27, 2017). "Brody File Exclusive: President Trump Says Persecuted Christians Will Be Given Priority As Refugees". The Brody File. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b J.A. (January 28, 2017). "Donald Trump gets tough on refugees". The Economist. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Connor, Phillip (October 5, 2016). "U.S. admits record number of Muslim refugees in 2016". Pew Research Center. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

... refugee status was given to 12,587 Syrians. Nearly all of them (99%) were Muslim and less than 1% were Christian.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b "Trump's claim that it is 'very tough' for Christian Syrians to get to the United States". Washington Post. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ "Fact check: Christian refugees 'unfairly' kept out?". Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Gambino, Lauren (September 2, 2016). "Trump and Syrian refugees in the US: separating the facts from fiction". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ http://www.sessions.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/6e9a95e6-3552-45f7-bb0c-4fd41f5a28ca/01.13.16-original-doj-nsd-list.pdf

- ^ Berger, Judson (June 22, 2016). "Anatomy of the terror threat: Files show hundreds of US plots, refugee connection". foxnews.com. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Nowrasteh, Alex (January 26, 2017). "Guide to Trump's Executive Order to Limit Migration for "National Security" Reasons". Cato Institute. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Jackson, Brooks, and Eugene Kiely, Lori Robertson and Robert Farley (February 1, 2017). "Facts on Trump's Immigration Order". FactCheck.org.

Cato Institute, September 13, 2016: The chance that an American would be killed in a terrorist attack committed by a refugee was 1 in 3.64 billion a year...actually only 40 of the foreign-born individuals on Sessions' list were convicted of carrying out or attempting to carry out a terrorist attack in the U.S... Many of the investigations started based on a terrorism tip like, for instance, the suspect wanting to buy a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. However, the tip turned out to be groundless and the legal saga ended with only a mundane conviction of receiving stolen cereal.

{{cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^

"Profiles". Mother Jones. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

Abuali was charged with getting two truckloads of stolen cereal. The FBI had been told that one of the men may have tried to buy a rocket propelled grenade, but the tip didn't pan out. Though the case has no clear terrorist links, the DOJ has classified it as terrorism-related.

- ^

Lewin, Tamar (November 28, 2001). "A Nation Challenged". The New York Times. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

The federal criminal charges against 93 people in the terrorist investigation range from relatively minor counts that seem to have only the most tenuous connection to terrorism to a few that involve actions that would raise suspicions in any climate.

- ^ Preston, Julia (June 18, 2016). "Many What-Ifs in Donald Trump's Plan for Migrants". The New York Times.

- ^ Lee, Michelle Ye Hee (June 15, 2016). "Donald Trump's almost-true claim that the president has power to ban 'any class of persons'". The Washington Post.

- ^ Lee, Michelle Ye Hee (January 29, 2017). "What you need to know about the terrorist threat from foreigners and Trump's executive order". The Washington Post.

- ^ Bennett, Brian (January 29, 2017). "Travel ban is the clearest sign yet of Trump advisors' intent to reshape the country". L.A. Times. Washington. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Perez, Evan; Brown, Pamela; Liptak, Kevin (January 29, 2017). "Inside the confusion of the Trump executive order and travel ban". CNN. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Carrie (January 27, 2017). "Key Justice Dept. Office Won't Say If It Approved White House Executive Orders". NPR. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Shear, Michael D.; Feuer, Alan (January 28, 2017). "Judge Blocks Part of Trump's Immigration Order". The New York Times.

- ^ "Trump Team Kept Plan for Travel Ban Quiet". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "White House Defends Executive Order Barring Travelers From Certain Muslim Countries". The Wall Street Journal. January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Perez, Evan; Brown, Pamela; Liptak, Kevin (January 30, 2017). "Inside the confusion of the Trump executive order and travel ban". CNN Politics. Turner Broadcasting System. CNN. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

Homeland Security Secretary John Kelly and Department of Homeland Security leadership saw the final details shortly before the order was finalized, government officials said.

- ^ Cheney, Kyle; Nelson, Louis; Conway, Madeline (January 31, 2017). "DHS chief promises to carry out Trump's immigration order 'humanely'". Politico.

Along with confusion surrounding the order's implementation, reports also trickled out over the weekend that top administration officials, among them Kelly and Defense Secretary James Mattis, had not been consulted in crafting the order and were not aware of it until shortly before it was signed last week. On Tuesday, Kelly pushed back against those reports, telling reporters that he "did know it was under development" and had seen at least two drafts of the order.

- ^ "Trump Signs Orders to Rebuild the Military, Block Terrorists". January 27, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ Ceremonial Swearing-in of Defense Secretary Mattis. C-SPAN. January 30, 2017. Event occurs at 2:46.

- ^ Shear, Michael D.; Nixon, Ron (January 29, 2017). "How Trump's Rush to Enact an Immigration Ban Unleashed Global Chaos".

- ^ Hensley, Nicole (January 29, 2017). "Rudy Giuliani says Trump tasked him to craft 'Muslim ban'". Daily News. New York. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Full Video: Trump lays out his 'Contract with America'". MSN. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Wang, Amy B. "Trump asked for a 'Muslim ban', Giuliani says — and ordered a commission to do it 'legally'". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "EXECUTIVE ORDER: PROTECTING THE NATION FROM FOREIGN TERRORIST ENTRY INTO THE UNITED STATES". January 27, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Berman, Mark (January 30, 2017). "Trump and his aides keep justifying the entry ban by citing attacks it couldn't have prevented". Washington Post. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

when Trump announced Friday that he was suspending travel from seven Muslim-majority countries, his order mentioned the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks three times.

- ^ Blaine, Kyle; Horowitz, Julia (January 29, 2017). "How the Trump administration chose the 7 countries in the immigration executive order". CNN. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

The executive order specifically invoked the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

- ^ a b Siddiqui, Sabrina (January 27, 2017). "Trump signs 'extreme vetting' executive order for people entering the US". Guardian. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

While announcing his executive action at the Department of Defense on Friday, Trump summoned the memory of the 9/11 terror attacks, saying 'we will never forget the lessons of 9/11, nor the heroes who have lost their lives at the Pentagon.' However, none of the 19 hijackers who committed those attacks were from countries cited in the order.

- ^ Melby, Caleb; Migliozzi, Blacki; Keller, Michael (January 27, 2017). "Trump's Immigration Ban Excludes Countries With Business Ties". Bloomberg News. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ "Trump's Immigration Freeze Omits Those Linked To Deadly Attacks In U.S." NPR. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Post, David G. (January 30, 2017). "Was Trump's executive order an impeachable offense?". Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c Liptak, Adam (January 28, 2017). "President Trump's Immigration Order, Annotated". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Shear, Michael D.; Cooper, Helene (January 27, 2017). "Trump Bars Refugees and Citizens of 7 Muslim Countries". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Dewan, Angela; Smith, Emily (January 30, 2017). "What it's like in the 7 countries on Trump's travel ban list". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Diamond, Jeremy; Almasy, Steve. "Trump's immigration ban sends shockwaves". CNN. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Blaine, Kyle; Horowitz, Julia (January 30, 2017). "How the Trump administration chose the 7 countries in the immigration executive order". CNN.

- ^ a b c Trump, Donald (February 1, 2017). "PROTECTING THE NATION FROM FOREIGN TERRORIST ENTRY INTO THE UNITED STATES". Federal Register. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ "8 U.S. Code § 1187 - Visa waiver program for certain visitors". law.cornell.edu. Cornell University Law School. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Over 100,000 visas revoked by immigration ban, government lawyer reveals". nbcnews.com. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Gerstein, Josh (January 31, 2017). "State Department notice revoking visas under Trump order released". Politico. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ Ramotowski, Edward. "revocation order". Politico. United States Department of State. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Full Executive Order Text: Trump's Action Limiting Refugees Into the U.S." The New York Times. January 27, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ McKay, Hollie (January 25, 2017). "U.S.-backed Iraqi fighters say Trump's refugee ban feels like 'betrayal'". Fox News Channel. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- ^ "Judges temporarily block part of Trump's immigration order, WH stands by it". CNN. January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Green, Emma (January 27, 2017). "Where Christian Leaders Stand on Trump's Refugee Policy". The Atlantic. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Bulos, Nabi (January 29, 2017). "Trump's refugee policy raises a question: How do you tell a Christian from a Muslim?". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Dearden, Lizzie (January 28, 2017). "Donald Trump immigration ban: Most Isis victims are Muslims despite President's planned exemption for Christians". Independent. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Trump's refugee and travel suspension: Key points". BBC News. January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Nicholas, Peter; Nicholas, Peter (January 28, 2017). "White House Defends Executive Order Barring Travelers From Certain Muslim Countries". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Nordland, Rod (November 19, 2011). "Afghanistan Has Big Plans for Biometric Data". The New York Times. Retrieved April 24, 2012.

- ^ "US visitors may have to reveal social media passwords to enter country". Ars Technica. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ^ "Homeland Security Failed to Adopt Plan to Vet Visa Applicants' Social Media". NBC News. Retrieved 2017-02-08.

- ^ Says, Hocuspocus13. "Homeland Security Secretary: We Are Developing What Extreme Vetting Might Look Like". Retrieved 2017-02-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Shear, Michael D.; Feuer, Alan (January 28, 2017). "Judge Blocks Part of Trump's Immigration Order". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c Shear, Michael (January 29, 2017). "White House Official, in Reversal, Says Green Card Holders Won't Be Barred". The New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Tears and detention for US visitors as Trump travel ban hits". Fox News Channel. January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Statement By Secretary John Kelly On The Entry Of Lawful Permanent Residents Into The United States". Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Bierman, Noah (February 1, 2017). "Trump administration further clarifies travel ban, exempting green card holders". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Josh Gerstein (February 1, 2017). "White House tweaks Trump's travel ban to exempt green card holders". Politico. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Merica, Dan. "How Trump's travel ban affects green card holders and dual citizens - CNNPolitics.com". Cnn.com. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "Presidential executive order on inbound migration to US". Foreign and Commonwealth Office. January 29, 2017. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Draft executive order would begin 'extreme vetting' of immigrants and visitors to the U.S."

- ^ "Read the draft of the executive order on immigration and refugees".

- ^ David, Sherfinski (February 1, 2017). "Chuck Schumer wants delay on Rex Tillerson vote, possibly other nominees, after executive order". The Washington Times.

- ^ "Trump says he will order 'safe zones' for Syria". January 25, 2017.

- ^ "Saudis tell Trump they support safe zones for refugees in Syria". Financial Times.

- ^ "The Latest: Sanders says Trump may be right about his voters". Tulsa World. February 2, 2017 – via Associated Press.

President Donald Trump and the king of Jordan have discussed with the possibility of establishing safe zones for refugees in Syria.

- ^ "Lebanon backs returning Syrian refugees to 'safe zones'". U.S. News and World Report. February 3, 2017.

- ^ "Russia says Trump should be more specific on Syria safe zones plan". Reuters. February 1, 2017.

- ^ Francis, Ellen (February 3, 2017). "UNHCR chief says safe zones would not work in Syria". Reuters.

- ^ Jorgensen, Sarah (January 29, 2017). "Syrian Christian family, visas in hand, turned back at airport". CNN. Turner Broadcasting System. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b "Trump executive order: Refugees detained at US airports". BBC News. January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Diamond, Jeremy; Almasy, Steve. "Trump's immigration ban sends shockwaves". CNN. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Yuhas, Raya Jalabi Alan (January 28, 2017). "Federal judge stays deportations under Trump Muslim country travel ban". The Guardian. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Protests Spread at Airports Nationwide Over Trump's Executive Order". ABC News. January 28, 2017.

- ^ Wadhams, Nick; Sink, Justin; Palmeri, Christopher; Van Voris, Bob (January 29, 2017). "Judges Block Parts of Trump's Order on Muslim Nation Immigration". Bloomberg. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ St. Clair, Stacy; Wong, Grace (January 29, 2017). "Chicago-area lawyers flock to O'Hare to help travelers held at airport". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ "Department of Homeland Security Response To Recent Litigation". United States Department of Homeland Security.

- ^ Torbati, Yeganeh; Mason, Jeff; Rosenberg, Mica (January 29, 2017). "Chaos, anger as Trump order halts some Muslim immigrants". Reuters. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (January 30, 2017). "Trump's executive order spurs Facebook and Twitter checks at the border". The Verge. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ CNN, Laura Jarrett. "Over 100,000 visas revoked, government lawyer says in Virginia court". cnn.com. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Caldwell, Alicia A. (February 3, 2017). "State Says Fewer Than 60,000 Visas Revoked Under Order". ABC News. The Associated Press. Retrieved 2017-02-03.

- ^ "State Dept: Fewer than 60,000 Visas Canceled by Trump Order". Fox News (from the Associated Press). February 3, 2017. Retrieved February 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Glenn Kessler (January 30, 2017). "The number of people affected by Trump's travel ban: About 90,000". Washington Post.

- ^ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/01/31/us/politics/trump-ban-immigrants-refugees.html?_r=0

- ^ Ron Nixon (January 31, 2017). "More People Were Affected by Travel Ban Than Trump Initially Said". New York Times.

- ^ Kessler, Glenn. "Fact check: White House claims 109 affected by travel ban - it's more like 90,000". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Trump's Immigration Ban: Who Is Barred and Who Is Not". January 31, 2017.

- ^ "Trump executive order prompts Google to recall staff". BBC News. January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Worley, Will (January 28, 2017). "Google recalling staff from abroad following Trump's immigration ban". The Independent. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Levine, Dan (January 30, 2017). "Washington state to sue over travel ban, pressures on Trump grow". Reuters. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Isidore, Chris (2017-01-31). "Amazon, Expedia back lawsuit opposing Trump travel ban". CNNMoney. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ "CED People: Steve Odland". Center for Economic Development. Retrieved February 7, 2017.

- ^ Norton, Steven. "Trump Immigration Order Unlikely to Affect Tech Hiring". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "How Donald Trump's immigration edict will affect American tourism". Economist (Gulliver Blog). January 30, 2017.

- ^ http://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/north-america/united-states/articles/trump-travel-ban-has-casts-a-shadow-over-us-tourism/

- ^ http://thehill.com/policy/transportation/317003-trumps-travel-ban-could-hamper-us-tourism-business

- ^ Erdbrink, Thomas; Gettleman, Jeffrey (January 27, 2017). "In Iran, Shock and Bewilderment Over Trump Visa Crackdown". The New York Times. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ a b Jr, Donald G. Mcneil (2017-02-06). "Trump's Travel Ban, Aimed at Terrorists, Has Blocked Doctors". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-07.

- ^ a b Jena, Anupam B. (2017-02-03). "Trump's Immigration Order Could Make It Harder To Find A Psychiatrist Or Pediatrician". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved 2017-02-04.

- ^ a b Fandos, Nicholas (January 29, 2017). "Some Top Republicans in Congress Criticize Trump's Refugee Policy". New York Times. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Owen, Paul; Siddiqui, Sabrina (January 28, 2017). "US refugee ban: Trump decried for 'stomping on' American values". The Guardian. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Greenwood, Max (January 28, 2017). "Sanders: Trump 'fostering hatred' with refugee ban". The Hill. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Timm, Jane C. (January 28, 2017). "Advocacy, Aid Groups Condemn Trump Order as 'Muslim Ban'". NBC News. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Jacobs, Harrison (January 28, 2017). "HILLARY CLINTON: 'This is not who we are'". Business Insider. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Kevin Lewis on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ Ryan, Paul (January 27, 2017). "Statement on President Trump's Executive Actions on National Security" (Press Release). Speaker.gov. United States House of Representatives. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Sabur, Rozina; Swinford, Steven (January 29, 2017). "Donald Trump's ban on Muslims: Global backlash as ministers told to fight for British citizens' rights - but president is defiant". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Collins, Steve (January 28, 2017). "Maine's senators denounce Trump's ban on immigration from 7 Muslim countries". Sun Journal.

- ^ Jeffrey Gettleman (January 31, 2017). "State Dept. Dissent Cable on Trump's Ban Draws 1,000 Signatures". New York Times.

- ^ Labott, Elise (January 30, 2017). "State Department diplomats may oppose Trump order". CNN Politics. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- ^ "Dissent Channel: Alternatives to closing doors in order to secure our borders" (PDF).

- ^ Felicia Schwartz (February 1, 2017). "State Department Dissent, Believed Largest Ever, Formally Lodged". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ Svrluga, Susan (January 28, 2017). "40 Nobel laureates, thousands of academics sign protest of Trump immigration order". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b Bump, Philip (February 2, 2017). "Do Americans support Trump's immigration action? Depends on who's asking, and how". Washington Post.

- ^ Shepard, Steven. "Polls fuel both sides in travel ban fight". Politico. Retrieved February 9, 2017.

- ^ a b "Trump's refugee and travel suspension: World reacts". BBC News. January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Chmaytelli, Maher; Noueihed, Lin. "Global backlash grows against Trump's immigration order". Reuters.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Hjelmgaard, Kim (January 29, 2017). "World weighs in on Trump ban with rebukes and praise". USA Today.

{{cite news}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ Sengupta, Somini (February 1, 2017). "U.N. Leader Says Trump Visa Bans 'Violate Our Basic Principles'". New York Times.

- ^ "U.N. rights chief says Trump's travel ban is illegal". Reuters. January 30, 2017.

- ^ Erickson, Amanda (January 28, 2017). "Here's how the world is responding to Trump's ban on refugees, travelers from 7 Muslim nations". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland; Sherlock, Ruth (January 28, 2017). "Donald Trump bans citizens of seven muslim majority countries as visa-holding travellers are turned away from US borders". The Telegraph. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

She proceeded to praise Britain's record on refugees, but avoided commenting on US policy.

- ^ "Theresa May fails to condemn Donald Trump on refugees". BBC News. January 28, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

Prime Minister Theresa May has been criticised for refusing to condemn President Donald Trump's ban on refugees entering the US ... But when pressed for an answer on Donald Trump's controversial refugee ban she first of all, uncomfortably, avoided the question. Then on the third time of asking she would only say that on the United States policy on refugees it was for the US

- ^ Farmer, Ben (January 29, 2017), Swinford, Steven (ed.), "Donald Trump petition: MPs to debate whether UK state visit should go ahead as more than 1.5m call for it to be cancelled", The Telegraph, retrieved January 29, 2017

- ^ "Theresa May finally passes judgment on Donald Trump's immigration ban". The Independent. January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Knecht, Eric (January 28, 2017). "Trump bars door to refugees, visitors from seven mainly Muslim nations". Reuters. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ^ Malcolm Turnbull refuses to denounce Trump's travel ban, The Guardian, January 30, 2017, retrieved January 3, 2017

- ^ Murphy, Katharine; Doherty, Ben (February 2, 2017). "Australia struggles to save refugee agreement after Trump's fury at 'dumb deal'". The Guardian. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Statement of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Islamic Republic of Iran". Iranian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. January 28, 2017. 436947. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Ellis, Ralph; Mazloumsaki, Sara; Moshtaghian, Artemis (January 29, 2017) [2017-01-28]. "Iran to take 'reciprocal measures' after Trump's immigration order" (updated ed.). CNN. Archived from the original on January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ AP Analysis: Trump travel ban risks straining Mideast ties

- ^ "UAE Becomes First Muslim-majority Country to Back Trump's Executive Order". Haaretz. February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "UAE says Trump travel ban an internal affair, most Muslims unaffected". Reuters. February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ "Christian leaders denounce Donald Trump 'Muslim ban'". January 30, 2017. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Some of the U.S.'s most important Catholic leaders are condemning Trump's travel ban". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Trump's action banning refugees brings outcry from U.S. church leaders". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ a b c Allen, Bob (January 30, 2017). "Baptists weigh in on Muslim travel ban". Baptist News Global. Retrieved February 2, 2017.

- ^ "Statement by the President on International Holocaust Remembrance Day" (Press release). whitehouse.gov. The White House, Office of the Press Secretary. January 27, 2017. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Koran, Laura (January 28, 2017). "Jewish groups pan Trump for signing refugee ban on Holocaust Remembrance Day". CNN. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Fox-Belivacqua, Marisa (January 28, 2017). "Holocaust survivors respond to Trump's refugee ban with outrage, empathy". Haaretz. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Nelson, Ellot (January 31, 2017). "The KKK And Their Friends Are Overjoyed With President Trump's First 10 Days". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Gillman, Todd J. (January 29, 2017). "This Day in Trump, Day 9: Muslim ban fallout". Dallas News. Retrieved February 1, 2017.

- ^ Jordans, Frank (January 29, 2017). "European leaders oppose Trump travel ban, far right applauds". Stars and Stripes. Associated Press.

- ^ "European leaders oppose Trump travel ban; far right applauds". Chicago Tribune. January 29, 2017. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ CNN, Angela Dewan. "French far-right leader Le Pen applauds Trump's travel ban". Retrieved February 2, 2017.

{{cite news}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ a b Warrick, Joby (January 29, 2017). "Jihadist groups hail Trump's travel ban as a victory". Washington Post. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ "Warren, Lewis, headline Congressional members at Trump immigration ban protests". USA Today. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Sottek, T (January 29, 2017). "Google co-founder Sergey Brin joins protest against immigration order at San Francisco airport". Forbes. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Mac, Ryan (January 29, 2017). "Y Combinator's Sam Altman At Airport Protest: This May Be A Defining Moment When People Oppose Trump". Forbes. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ Langmaid, Tim; Hackney, Deanna (January 29, 2017). "The ban that descended into chaos: What we know". CNN Politics. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ a b c Adam Liptak, Where Trump's Travel Ban Stands, New York Times (February 5, 2017).

- ^ Edward Isaac Dovere, Democratic state attorneys general vow action against refugee order, Politico (January 29, 2017).

- ^ Official Twitter account of New York State Attorney General Eric T. Schneiderman [1], "Statement from 16 AG's..." (January 29, 2017)

- ^ Barrett, Devlin (January 30, 2017). "Acting Attorney General Orders Justice Dept. Not to Defend Trump's Immigration Ban". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Roy, Jessica (January 30, 2017). "Why people are calling the acting attorney general's firing the 'Monday Night Massacre'". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Zelizer, Julian. "Monday night massacre is a wake-up call to Senate Democrats". CNN. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ "Monday Night Massacre: Trump fires acting Attorney General". MSNBC. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ "Trump's 'Monday Night Massacre': What The Legal Community Is Saying". Fortune. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ "AG Bob Ferguson files lawsuit — first by any state — to invalidate Trump's order". The Seattle Times. 2017-01-30. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ Landler, Mark (2017-02-04). "Trump Officials Move to Appeal Ruling Blocking Immigration Order". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-05.

- ^ Melvin, Don; Arouzi, Ali; Walters, Shamar (February 4, 2017). "Homeland Security Suspends Implementation of President Trump's Travel Ban". NBC News. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

- ^ Special Collection: Civil Rights Challenges to Trump Immigration/Refugee Orders, University of Michigan Law School's Civil Rights Litigation Clearinghouse (last accessed January 31, 2017).

External links

- Full text of the executive order via the Federal Register

- Fact Sheet by the United States Department of Homeland Security

- Questions and Answers about the Executive Order. U.S. Customs and Border Protection

- Court Challenge:

- Relevant court filings and orders

- Office of Legal Counsel memorandum on the order's legality obtained due to a FOIA request via the New York Times

- Site Created For Appeal Case in the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals

- Executive Order 13769

- 2017 in American politics

- 2017 works

- Anti-immigration politics in the United States

- Iran–United States relations

- Iraq–United States relations

- January 2017 events in the United States

- Libya–United States relations

- Somalia–United States relations

- Sudan–United States relations

- Syria–United States relations

- Trump administration controversies

- United States immigration law

- United States–Yemen relations

- Works about immigration to the United States