James Naismith: Difference between revisions

Rescuing 2 sources and tagging 0 as dead. #IABot (v1.5beta) |

|||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

At Springfield YMCA, Naismith struggled with a rowdy class that was confined to indoor games throughout the harsh [[New England]] winter and thus was perpetually short-tempered. Under orders from Dr. Luther Gulick, head of Springfield YMCA Physical Education, Naismith was given 14 days to create an indoor game that would provide an "athletic distraction": Gulick demanded that it would not take up much room, could help its track athletes to keep in shape<ref name=mcgill/> and explicitly emphasized to "make it fair for all players and not too rough."<ref name=hofsummary/> |

At Springfield YMCA, Naismith struggled with a rowdy class that was confined to indoor games throughout the harsh [[New England]] winter and thus was perpetually short-tempered. Under orders from Dr. Luther Gulick, head of Springfield YMCA Physical Education, Naismith was given 14 days to create an indoor game that would provide an "athletic distraction": Gulick demanded that it would not take up much room, could help its track athletes to keep in shape<ref name=mcgill/> and explicitly emphasized to "make it fair for all players and not too rough."<ref name=hofsummary/> |

||

In his attempt to think up a new game, Naismith was guided by three main thoughts.<ref name=museumtimeline/> Firstly, he analyzed the most popular games of those times ([[Rugby union|rugby]], [[lacrosse]], soccer, football, [[ice hockey|hockey]], and [[baseball]]); Naismith noticed the hazards of a ball and concluded that the big soft soccer ball was safest. Secondly, he saw that most physical contact occurred while running with the ball, dribbling or hitting it, so he decided that passing was the only legal option. Finally, Naismith further reduced body contact by making the goal unguardable, namely placing it high above the player's heads. To score goals, he forced the players to throw a soft lobbing shot that had proven effective in his old favorite game ''duck on a rock''. Naismith christened this new game "Basket Ball"<ref name=museumtimeline/> and put his thoughts together in [[James Naismith's Original Rules of Basketball|13 basic rules]].<ref name=13rules>{{cite web |

In his attempt to think up a new game, Naismith was guided by three main thoughts.<ref name=museumtimeline/> Firstly, he analyzed the most popular games of those times ([[Rugby union|rugby]], [[lacrosse]], soccer, football, [[ice hockey|hockey]], and [[baseball]]); Naismith noticed the hazards of a ball and concluded that the big soft soccer ball was safest. Secondly, he saw that most physical contact occurred while running with the ball, dribbling or hitting it, so he decided that passing was the only legal option. Finally, Naismith further reduced body contact by making the goal unguardable, namely placing it high above the player's heads. To score goals, he forced the players to throw a soft lobbing shot that had proven effective in his old favorite game ''duck on a rock''. Naismith christened this new game "Basket Ball"<ref name=museumtimeline/> and put his thoughts together in [[James Naismith's Original Rules of Basketball|13 basic rules]].<ref name=13rules>{{cite web |

||

|last=Naismith |

|last=Naismith |

||

|first=James |

|first=James |

||

| Line 91: | Line 91: | ||

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080408185146/http://www.ncaa.org/champadmin/basketball/original_rules.html |

|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20080408185146/http://www.ncaa.org/champadmin/basketball/original_rules.html |

||

|archivedate=2008-04-08 |

|archivedate=2008-04-08 |

||

|deadurl= |

|deadurl=yes |

||

|df= |

|df= |

||

}}</ref> |

}}</ref> |

||

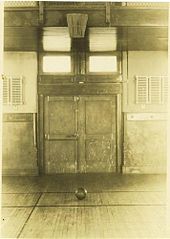

The first game of "Basket Ball" was played in December 1891. In a handwritten report, Naismith described the circumstances of the inaugural match; in contrast to modern [[basketball]], the players played nine versus nine, handled a [[association football|soccer]] ball, not a basketball, and instead of shooting at two hoops, the goals were a pair of peach baskets: "When Mr. Stubbins brot {{sic}} up the peach baskets to the gym I secured them on the inside of the railing of the gallery. This was about 10 feet from the floor, one at each end of the gymnasium. I then put [[James Naismith's Original Rules of Basketball|the 13 rules]] on the bulletin board just behind the instructor's platform, secured a soccer ball and awaited the arrival of the class... The class did not show much enthusiasm but followed my lead... I then explained what they had to do to make goals, tossed the ball up between the two center men & tried to keep them somewhat near the rules. Most of the fouls were called for running with the ball, though tackling the man with the ball was not uncommon."<ref name=firstgame>{{cite web |

The first game of "Basket Ball" was played in December 1891. In a handwritten report, Naismith described the circumstances of the inaugural match; in contrast to modern [[basketball]], the players played nine versus nine, handled a [[association football|soccer]] ball, not a basketball, and instead of shooting at two hoops, the goals were a pair of peach baskets: "When Mr. Stubbins brot {{sic}} up the peach baskets to the gym I secured them on the inside of the railing of the gallery. This was about 10 feet from the floor, one at each end of the gymnasium. I then put [[James Naismith's Original Rules of Basketball|the 13 rules]] on the bulletin board just behind the instructor's platform, secured a soccer ball and awaited the arrival of the class... The class did not show much enthusiasm but followed my lead... I then explained what they had to do to make goals, tossed the ball up between the two center men & tried to keep them somewhat near the rules. Most of the fouls were called for running with the ball, though tackling the man with the ball was not uncommon."<ref name=firstgame>{{cite web |

||

| Line 277: | Line 277: | ||

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20130319212618/http://www.hoophall.com/hall-of-famers/tag/james-naismith Basketball Hall of Fame profile] |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20130319212618/http://www.hoophall.com/hall-of-famers/tag/james-naismith Basketball Hall of Fame profile] |

||

*[http://www.naismithmuseum.com/ Naismith Museum] in Mississippi Mills, Ontario, Canada; has information about Naismith Foundation (See "About Us") |

*[http://www.naismithmuseum.com/ Naismith Museum] in Mississippi Mills, Ontario, Canada; has information about Naismith Foundation (See "About Us") |

||

*[http://www.halloffame.fiba.com/pages/eng/hof/indu/p/lid_9061_newsid/18082/contBio.html FIBA Hall of Fame profile] |

*[https://web.archive.org/web/20070930160126/http://www.halloffame.fiba.com/pages/eng/hof/indu/p/lid_9061_newsid/18082/contBio.html FIBA Hall of Fame profile] |

||

*{{worldcat id|id=lccn-n91-122143}} |

*{{worldcat id|id=lccn-n91-122143}} |

||

Revision as of 08:16, 27 July 2017

James Naismith holding a basketball | |

| Biographical details | |

|---|---|

| Born | November 6, 1861 Almonte, Ontario, Canada |

| Died | November 28, 1939 (aged 78) Lawrence, Kansas, USA |

| Alma mater | McGill University |

| Coaching career (HC unless noted) | |

| 1898–1907 | Kansas |

| Head coaching record | |

| Overall | 55–60 |

| Accomplishments and honors | |

| Awards | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 1959 | |

| College Basketball Hall of Fame Inducted in 2006 | |

James Naismith (November 6, 1861 – November 28, 1939) was a Canadian-American physical educator, physician, chaplain, sports coach and innovator.[1] He invented the game of basketball at age 30 in 1891. He wrote the original basketball rule book and founded the University of Kansas basketball program.[2] Naismith lived to see basketball adopted as an Olympic demonstration sport in 1904 and as an official event at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, as well as the birth of the National Invitation Tournament (1938) and the NCAA Tournament (1939).

Born in Canada, Naismith studied physical education at McGill University in Montreal before moving to the United States, where he designed the game in late 1891 while teaching at the International YMCA Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts.[3] Seven years after inventing basketball, Naismith received his medical degree in Denver in 1898. He then arrived at the University of Kansas, later becoming the Kansas Jayhawks' athletic director and coach.[4] While a coach at Kansas, Naismith coached Phog Allen, who later became the coach at Kansas for 39 seasons, beginning a lengthy and prestigious coaching tree. Allen then went on to coach legends including Adolph Rupp and Dean Smith, among others, who themselves coached many notable players and future coaches.[5]

Early years

Naismith was born in 1861 in Almonte (now part of Mississippi Mills), Ontario, Canada to Scottish immigrants.[6] He never had a middle name and never signed his name with the "A" initial. The "A" was added by someone in the administration at the University of Kansas.[nb 1]

Struggling in school but gifted in farm labor, Naismith spent his days outside playing catch, hide-and-seek, or duck on a rock, a medieval game in which a person guards a large drake stone from opposing players, who try to knock it down by throwing smaller stones at it. To play duck on a rock most effectively, Naismith soon found that a soft lobbing shot was far more effective than a straight hard throw, a thought that later proved essential for the invention of basketball.[7] Orphaned early in his life, Naismith lived with his aunt and uncle for many years and attended grade school at Bennies Corners near Almonte. Then he enrolled in Almonte High School, in Almonte, Ontario, from which he graduated in 1883.[7]

In the same year, Naismith entered McGill University in Montreal. Although described as a slight figure, standing 5 foot 10 ½ and listed at 178 pounds,[8] he was a talented and versatile athlete, representing McGill in Canadian football, lacrosse, rugby, soccer and gymnastics. He played center on the football team, and made himself some padding to protect his ears. It was for personal use, not team use.[9] He won multiple Wicksteed medals for outstanding gymnastics performances.[10] Naismith earned a BA in Physical Education (1888) and a Diploma at the Presbyterian College in Montreal (1890).[7] From 1891 on, Naismith taught physical education and became the first McGill director of athletics, but then left Montreal to become a physical education teacher at the YMCA International Training School in Springfield, Massachusetts.[10][11]

Springfield college: Invention of Basketball

At Springfield YMCA, Naismith struggled with a rowdy class that was confined to indoor games throughout the harsh New England winter and thus was perpetually short-tempered. Under orders from Dr. Luther Gulick, head of Springfield YMCA Physical Education, Naismith was given 14 days to create an indoor game that would provide an "athletic distraction": Gulick demanded that it would not take up much room, could help its track athletes to keep in shape[10] and explicitly emphasized to "make it fair for all players and not too rough."[8]

In his attempt to think up a new game, Naismith was guided by three main thoughts.[7] Firstly, he analyzed the most popular games of those times (rugby, lacrosse, soccer, football, hockey, and baseball); Naismith noticed the hazards of a ball and concluded that the big soft soccer ball was safest. Secondly, he saw that most physical contact occurred while running with the ball, dribbling or hitting it, so he decided that passing was the only legal option. Finally, Naismith further reduced body contact by making the goal unguardable, namely placing it high above the player's heads. To score goals, he forced the players to throw a soft lobbing shot that had proven effective in his old favorite game duck on a rock. Naismith christened this new game "Basket Ball"[7] and put his thoughts together in 13 basic rules.[12]

The first game of "Basket Ball" was played in December 1891. In a handwritten report, Naismith described the circumstances of the inaugural match; in contrast to modern basketball, the players played nine versus nine, handled a soccer ball, not a basketball, and instead of shooting at two hoops, the goals were a pair of peach baskets: "When Mr. Stubbins brot [sic] up the peach baskets to the gym I secured them on the inside of the railing of the gallery. This was about 10 feet from the floor, one at each end of the gymnasium. I then put the 13 rules on the bulletin board just behind the instructor's platform, secured a soccer ball and awaited the arrival of the class... The class did not show much enthusiasm but followed my lead... I then explained what they had to do to make goals, tossed the ball up between the two center men & tried to keep them somewhat near the rules. Most of the fouls were called for running with the ball, though tackling the man with the ball was not uncommon."[13] In contrast to modern basketball, the original rules did not include what is known today as the dribble. Since the ball could only be moved up the court via a pass early players tossed the ball over their heads as they ran up court. Also following each "goal" a jump ball was taken in the middle of the court. Both practices are obsolete in the rules of modern basketball.[14]

In a radio interview in January 1939, Naismith gave more details of the first game and the initial rules that were used:

- “I showed them two peach baskets I’d nailed up at each end of the gym, and I told them the idea was to throw the ball into the opposing team’s peach basket. I blew a whistle, and the first game of basketball began. … The boys began tackling, kicking and punching in the clinches. They ended up in a free-for-all in the middle of the gym floor. [The injury toll: several black eyes, one separated shoulder and one player knocked unconscious.] “It certainly was murder.” [Naismith changed some of the rules as part of his quest to develop a clean sport.] The most important one was that there should be no running with the ball. That stopped tackling and slugging. We tried out the game with those [new] rules (fouls), and we didn’t have one casualty.”[15]

By 1892, basketball had grown so popular on campus that Dennis Horkenbach (editor-in-chief of The Triangle, the Springfield college newspaper) featured it in an article called "A New Game",[6] and there were calls to call this new game "Naismith Ball", but Naismith refused.[7] By 1893, basketball was introduced internationally by the YMCA movement.[6] From Springfield, Naismith went to Denver where he acquired a medical degree and in 1898 he joined the University of Kansas faculty at Lawrence, Kansas after coaching at Baker University.[8]

The family of Lambert G. Will has claimed that Dr. Naismith borrowed components for the game of basketball from Will to dispute Naismith's sole creation of the game, citing alleged photos and letters.[16][17]

University of Kansas

The University of Kansas men's basketball program officially began following Naismith's arrival in 1898, which was six years after Naismith drafted the sport's first official rules. Naismith was not initially hired to coach basketball, but rather as a chapel director and physical education instructor.[18] In those early days, the majority of the basketball games were played against nearby YMCA teams, with YMCAs across the nation having played an integral part in the birth of basketball. Other common opponents were Haskell Indian Nations University and William Jewell College. Under Naismith, the team played only one current Big 12 school: Kansas State (once). Naismith was, ironically, the only coach in the program's history to have a losing record (55–60).[19] However, Naismith coached Forrest "Phog" Allen, his eventual successor at Kansas,[20] who went on to join his mentor in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame.[21] When Allen became a coach himself and told him that he was going to coach basketball at Baker University in 1904, Naismith discouraged him: "You can't coach basketball; you just play it."[10] Instead, Allen embarked on a coaching career that would lead him to be known as "the Father of Basketball Coaching." During his time at Kansas, Allen coached Dean Smith (1952 National Championship team) and Adolph Rupp (1922 Helms Foundation National Championship team). Smith and Rupp have joined Naismith and Allen as members of the Basketball Hall of Fame.

By the turn of the century, there were enough college teams in the East that the first intercollegiate competitions could be played out.[20] Although the sport continued to grow, Naismith long regarded the game as a curiosity and preferred gymnastics and wrestling as better forms of physical activity.[20] However, basketball became a demonstration sport at the 1904 Summer Olympics in St. Louis. As the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame reports, Naismith was also neither interested in self-promotion nor in the glory of competitive sports.[22] Instead, he was more interested in his physical education career, receiving an honorary PE Masters degree in 1910,[7] patrolled the Mexican border for four months in 1916, traveled to France, published two books (A Modern College in 1911 and Essence of a Healthy Life in 1918). He took American citizenship in 1925.[7] In 1909, Naismith's duties at Kansas were redefined as a Professorship; he served as the de facto athletic director at Kansas for much of the early 20th century.

In 1935, the National Association of Basketball Coaches (created by Naismith's pupil Phog Allen) collected money so that the 74-year-old Naismith could witness the introduction of basketball into the official Olympic sports program of the 1936 Summer Olympic Games.[22] There, Naismith handed out the medals to three North American teams: United States, for the gold medal, Canada, for the silver medal, and Mexico, for their bronze medal win.[23] During the Olympics, he was named the honorary president of the International Basketball Federation.[7] When Naismith returned he commented that seeing the game played by many nations was the greatest compensation he could have received for his invention.[20] In 1937, Naismith played a role in the formation of the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball, which later became the National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA).[24]

Naismith became professor emeritus in Kansas when he retired in 1937 at the age of 76. Including his years as coach, Naismith served as athletic director and faculty at the school for a total of almost 40 years. Naismith died in 1939 after he suffered a fatal brain hemorrhage. He was interred at Memorial Park Cemetery in Lawrence, Kansas. His masterwork "Basketball — its Origins and Development" was published posthumously in 1941.[7] In Lawrence, Kansas, James Naismith has a road named in his honor, Naismith Drive, which runs in front of Allen Fieldhouse (the official address of Allen Fieldhouse is 1651 Naismith Drive), the university's basketball facility. The university also named the court in Allen Fieldhouse James Naismith Court in his honor, despite Naismith having the worst record in school history. Naismith Hall, a college residential dormitory, is located on the northeastern edge of 19th Street and Naismith Drive.[25]

Head coaching record

In 1898, Naismith became the first basketball coach of the University of Kansas. He compiled a record of 55–60 and is ironically the only losing coach in Kansas history.[19] Naismith is at the beginning of massive and prestigious coaching tree, as he coached Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame coach Phog Allen, who himself coached Hall of Fame coaches Dean Smith, Adolph Rupp, and Ralph Miller who all coached future coaches as well.[20]

| Season | Team | Wins | Losses | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1898–99 | Kansas | 7 | 4 | .636 |

| 1899–1900 | Kansas | 3 | 4 | .429 |

| 1900–01 | Kansas | 4 | 8 | .333 |

| 1901–02 | Kansas | 5 | 7 | .417 |

| 1902–03 | Kansas | 7 | 8 | .467 |

| 1903–04 | Kansas | 5 | 8 | .385 |

| 1904–05 | Kansas | 5 | 6 | .455 |

| 1905–06 | Kansas | 12 | 7 | .632 |

| 1906–07 | Kansas | 7 | 8 | .467 |

| Total | Kansas | 55 | 60 | .478 |

Legacy

Naismith invented the game of basketball and wrote the original 13 rules of this sport as opposed to the NBA rule book which features 66 pages.[22] The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Massachusetts is named in his honor, and he was an inaugural inductee in 1959.[22] The National Collegiate Athletic Association rewards its best players and coaches annually with the Naismith Awards, among them the Naismith College Player of the Year, the Naismith College Coach of the Year and the Naismith Prep Player of the Year. After the Olympic introduction to men's basketball in 1936, women's basketball became an Olympic event in Montreal during the 1976 Summer Olympics.[26] Naismith was also inducted into the Canadian Basketball Hall of Fame, the Canadian Olympic Hall of Fame, the Canadian Sports Hall of Fame, the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame, the Ottawa Sports Hall of Fame, the McGill University Sports Hall of Fame, the Kansas State Sports Hall of Fame, FIBA Hall of Fame, and The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, which was named in his honor.[7][27] The FIBA Basketball World Cup trophy is named the "James Naismith Trophy" in his honour. On June 21, 2013, Dr. Naismith was inducted into the Kansas Hall of Fame during ceremonies in Topeka.[28]

Naismith's home town of Almonte, Ontario, hosts an annual 3-on-3 tournament for all ages and skill levels in his honor. Every year this event attracts hundreds of participants and involves over 20 half court games along the main street of the town. All proceeds of the event go to youth basketball programs in the area.

Basketball today is played by more than 300 million people worldwide, making it one of the most popular team sports.[10] In North America, basketball has produced some of the most-admired athletes of the 20th century. ESPN and the Associated Press both conducted polls to name the greatest North American athlete of the 20th century. Basketball player Michael Jordan came in first in the ESPN poll and second (behind Babe Ruth) in the AP poll. Both polls featured fellow basketball players Wilt Chamberlain (of KU, like Naismith) and Bill Russell in the Top 20.[29][30]

The original rules of basketball written by James Naismith in 1891, considered to be basketball's founding document, was auctioned at Sotheby's, New York in December, 2010. Josh Swade, a University of Kansas alumnus and basketball enthusiast, went on a crusade in 2010 to persuade moneyed alumni to considering bidding on and hopefully winning the document at auction to gift it to the University of Kansas. Swade eventually persuaded David G. Booth, a billionaire investment banker and KU alumnus, and his wife Suzanne Booth to commit to bidding at the auction. The Booths won the bidding and purchased the document for a record $4,338,500 USD, the most ever paid for a sports memorabilia item, and gifted the document to the University of Kansas.[31] Swade's project and eventual success are chronicled in a 2012 ESPN 30 for 30 documentary "There's No Place Like Home" and in a corresponding book, "The Holy Grail of Hoops: One Fan's Quest to Buy the Original Rules of Basketball".[32] The University of Kansas constructed an $18 million building named the Debruce Center, which houses the rules and opened in March 2016.[33]

Personal life

James Naismith was the second child of Margaret and John Naismith, two Scottish immigrants. His mother, Margaret Young, was born in 1833 and immigrated to Lanark County, Canada in 1852 as the fourth of 11 children.[7] His father, John Naismith, was born in 1833,[34] left Europe when he was 18, and also settled down in Lanark County. On June 20, 1894, Naismith married Maude Evelyn Sherman (1870–1937) in Springfield, MA, USA. The couple had five children: Margaret Mason (Stanley) (1895–1976), Helen Carolyn (Dodd) (1897–1980), John Edwin (1900–1986), Maude Ann (Dawe) (1904–1972) and James Sherman (1913–1980).[8] He was a member of the Pi Gamma Mu and Sigma Phi Epsilon fraternities.[8] Naismith was a Presbyterian minister, and was also remembered as a Freemason.[35] Maude Naismith died in 1937, and on June 11, 1939, he married his second wife Florence B. Kincaid. On November 19 of that year, Naismith suffered a major brain hemorrhage and died nine days later in his home located in Lawrence, Kansas.[36] Naismith was 78 years old.[37] Coincidentally, Naismith died eight months after the birth of the NCAA Basketball Championship, which today has evolved to one of the biggest sports events in North America. Naismith is buried with his first wife in Memorial Park Cemetery in Lawrence, Kansas.[38] Florence Kincaid died in 1977 at the age of 98 and is buried with her first husband, Dr. Frank B. Kincaid, in Elmwood Cemetery in Beloit, Kansas.

During his lifetime, Naismith held the following education and academic positions:[8]

| Location | Position | Period | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bennie's Corner Grade School (Almonte, Ontario) | Primary school | 1867–1875 | |

| Almonte High School | Secondary school | 1875–1877, 1881–83 | Dropped out and re-entered |

| McGill University | University student | 1883–87 | Bachelor of Arts in Physical Education |

| McGill University | Instructor in Physical Education | 1887–1890 | Gold Wickstead Medal (1887), Best All-Around Athlete; Silver Cup (1886), first prize for one-mile walk; Silver Wickstead Medal (1885), Best All-Around Athlete; Awarded one of McGill's first varsity letters |

| The Presbyterian College, Montreal | Education in Theology | 1887–1890 | Silver medal (1890), second highest award for regular and special honor work in Theology |

| Springfield College | Instructor in Physical Education | 1890–1895 | Invented "Basket Ball" in December 1891 |

| YMCA of Denver | Instructor in Physical Education | 1895–1898 | |

| University of Kansas | Instructor in Physical Education and Chapel Director | 1898–1909 | |

| University of Kansas | Basketball Coach | 1898–1907 | First-ever campus basketball coach |

| University of Kansas | Professor and University Physician | 1909–1917 | Hiatus from 1914 on due to World War I |

| First Kansas Infantry | Chaplain/Captain | 1914–1917 | Military service due to World War I |

| First Kansas Infantry (Mexican Border) | Chaplain | 1916 | |

| Military and YMCA secretary in France | Lecturer of Moral Conditions and Sex Education | 1917–1919 | |

| University of Kansas | Athletic Director | 1919–1937 | Emeritus in 1937 |

See also

References

Informational notes

- ^ In 1982 Dr. Naismith's only living child stated that his father never had the middle initial "A". The Basketball Hall of Fame also clarifies this as do other members of his family and personal friends of his. Historian Curtis J. Phillips has done extensive research on the subject

Citations

- ^ "James A. Naismith". Biography.com. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (2015-12-15). "Basketball's Birth, in James Naismith's Own Spoken Words". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-05-19.

- ^ Dr. Porter. (2005). Basketball: a biographical dictionary p.346.

- ^ David L. Porter. (2005). Basketball: A biographical dictionary. p.347.

- ^ "DEAN SMITH'S COACHING TREE DISPLAYS INCREDIBLE REACH ACROSS DECADES". BleacherReport.com.

- ^ a b c Laughead, George. "Dr. James Naismith, Inventor of Basketball". Kansas Heritage Group. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l

Laughead, George. "Dr. James Naismith". Kansas Heritage Group. Retrieved 2013-09-14.

In the late 1930s he played a role in what became the National Association of Intercollegiate Basketball.

- ^ a b c d e f Dodd, Hellen Naismith (January 6, 1959). "James Naismith's Resume". Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 19, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ John Melady (2013). Breakthrough!: Canada's Greatest Inventions and Innovations. Dundurn. p. 56.

- ^ a b c d e Zukerman, Earl (December 17, 2003). "McGill grad James Naismith, inventor of basketball". Varsity Sports News. McGill Athletics. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "A SHOT AT HISTORY: BASKETBALL". Retrieved 24 October 2013.

- ^ Naismith, James. "Dr. James Naismith's 13 Original Rules of Basketball". National Collegiate Athletic Association. Archived from the original on 2008-04-08. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Naismith, James. "James Naismith Handwritten Manuscript Detailing First Basketball Game". Heritage Auction Galleries. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Official basketball rules". International Basketball Federation. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Basketball's Birth, in James Naismith's Own Spoken Words". The New York Times. 16 December 2015.

- ^ Baruth, Philip. "Basketball Inventor". Basketball Inventor. Vermont Public Radio. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Fosty, George & Darril. "Basketball's Origins, Lingering Questions Remain". Box Score News. Retrieved 27 March 2011.

- ^ Chimelis, Ron. "Naismith Untold". Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 2, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ a b "Naismith's Record". kusports.com. Archived from the original on 2008-07-04. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e "James Naismith, A Kansas Portrait". Kansas Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Forrest C. "Phog" Allen". Naismith Museum And Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ a b c d "Hall of Fame Feature: James Naismith". Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^

"James Naismith, the inventor of basketball". collegesportsscholarships.com. Archived from the original on 2008-10-17. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kerkhoff, Blair. "The NAIA basketball tournament? Throw 32 teams in the same building and see which is the last one standing at the end of a weeklong frenzy". Retrieved 2008-09-30. [dead link]

- ^ "Google Maps Route". Google Maps. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ Jenkins, Sally. "History of women's basketball". WNBA.com. Women's National Basketball Association. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "James Naismith". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Naismith, Dr. James". Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- ^ "Top N. American athletes of the century". ESPN.com. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Top 100 athletes of the 20th century". USA Today. 1999-12-21. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Sotheby's - Auctions - James Naismith's Founding Rules of Basketball - Sotheby's".

- ^ "There's No Place Like Home - ESPN Films: 30 for 30".

- ^ "Updates from the DeBruce Center, future home of Naismith's 'Rules of Basket Ball' - Heard on the Hill / LJWorld.com".

- ^ "Dr. James A. Naismith and the Barony Naismiths".

- ^ "James Naismith". Grand Lodge of British Columbia and Yukon the great couple had five kids. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "Naismith Museum & Hall of Fame: Biography of James Naismith". Archived from the original on 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2008-12-12.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Schlabac, Mark (2005-01-15). "James Naismith Biography". bookrags.com. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ^ "James Naismith". Retrieved 2009-08-30.

Further reading

- Naismith, James (1996) [1941], Basketball: its origin and development, University of Nebraska Press, ISBN 0-8032-8370-9

{{citation}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthor=(help) - Rains, Rob; Carpenter, Hellen (2009). James Naismith: The Man Who Invented Basketball Temple University Press, ISBN 978-1-4399-0133-5

External links

- Basketball Hall of Fame profile

- Naismith Museum in Mississippi Mills, Ontario, Canada; has information about Naismith Foundation (See "About Us")

- FIBA Hall of Fame profile

- Template:Worldcat id

- 1861 births

- 1939 deaths

- American Presbyterian ministers

- American inventors

- American people of Canadian descent

- Basketball people from Ontario

- British emigrants to the United States

- Canada's Sports Hall of Fame inductees

- Canadian basketball coaches

- Canadian Presbyterian ministers

- Canadian emigrants to the United States

- Canadian inventors

- Canadian people of Scottish descent

- College men's basketball head coaches in the United States

- Creators of sports

- FIBA Hall of Fame inductees

- McGill University alumni

- History of basketball

- Kansas Jayhawks athletic directors

- Kansas Jayhawks men's basketball coaches

- McGill University faculty

- Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame inductees

- Persons of National Historic Significance (Canada)

- People from Lanark County

- Sportspeople from Lawrence, Kansas

- Springfield College (Massachusetts) alumni

- University of Kansas faculty