History of Iraq

The neutrality of this article is disputed. |

This article includes an overview from prehistory to the present in the region of the current state of Iraq in Mesopotamia. See also History of Mesopotamia, Chronology of the ancient orient, and History of the Middle East.

Prehistory

Neanderthal man lived in Iraq about 60,000 years ago. Neanderthal remains include those discovered at the Shanidar cave.

Ancient Times

The land area now known as modern Iraq was almost equivalent to Mesopotamia, the world's first civilization. The Mesopotamian plain between the two rivers Tigris and Euphrates (in Arabic, the Dijla and Furat, respectively), is part of the Fertile Crescent. Many dynasties and empires ruled the Mesopotamia region such as Sumer, Akkad, Assyria and Babylonia.

Sumerians and Akkadians

It was in Mesopotamia about 3000 BC where the Sumerian culture flourished. The civilized life that emerged at Sumer was shaped by two conflicting factors: the unpredictability of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, which at any time could unleash devastating floods that wiped out the entire populace, and the extreme richness of the river valleys, caused by centuries-old deposits of soil.

Eventually, the Sumerians had to battle other peoples. Some of the earliest of these wars were with the Elamites living in what is now western Iran. This frontier has been fought over repeatedly ever since; it is arguably the most fought over frontier in the world. Sumerian dominance was challenged by the Akkadians, who migrated up from the Arabian Peninsula. The Akkadians were a Semitic people, that is, they spoke a Semitic language.

In 2340 BC, the great Akkadian leader Sargon conquered Sumer and built the Akkadian Empire stretching over most of the Sumerian city-states and extending as far away as Lebanon. Sargon based his empire in the city of Akkad, which became the basis of the name of his people.

Sargon's ambitious empire lasted for only short time in the long time spans of Mesopotamian history. In 2125 BC, the Sumerian city of Ur in southern Mesopotamia rose up in revolt, and the Akkadian empire fell before a renewal of Sumerian city-states.

Babylonians, Mitanni, and Assyrians

After the later collapse of the Sumerian civilization, the people were reunited in 1700 BC by King Hammurabi of Babylon (1792-1750 BC), and the country flourished under the name of Babylonia. Babylonian rule encompassed a huge area covering most of the Tigris-Euphrates river valley from Sumer and the Persian Gulf. He extended his empire northward through the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys and westward to the coast of the Mediterranean Sea. After consolidating his gains under a central government at Babylon, he devoted his energies to protecting his frontiers and fostering the internal prosperity of the Empire. Hammurabi's dynasty, otherwise referred to as the First Dynasty of Babylon, ruled for about 200 years, until 1530 BC. Under the reign of this dynasty, Babylonia entered into a period of extreme prosperity and relative peace.

After Hammurabi's death, however, a tribe known as the Kassites began to attack Babylonia as early as the period when Hammurabi's son ruled the empire. Over the centuries, Babylonia was weakened by the Kassites. Finally, around 1530 BC (given in some sources as 1570 or 1595 BC), a Kassite Dynasty was set up in Babylonia.

The Mitanni, another culture, were meanwhile building their own powerful empire. They had only temporary importance; they were very powerful, but were around for only about 150 years. Still, the Mitanni were one of the major empires of this area in this time period, and they came to almost completely control and subjugate the Assyrians (who were located directly to the east of Mitanni and to the northwest of Kassite Babylonia).

The Assyrians, after they finally broke free of the Mitanni, were the next major power to assert themselves on Mesopotamia. After defeating and virtually annexing Mitanni, the Assyrians challenged Babylonia. They weakened Babylonia so much that the Kassite Dynasty fell from power; the Assyrians virtually came to control Babylonia, until revolts in turn deposed them and set up a new dynasty, known as the Second Dynasty of Isin. Nebuchadnezzar I (Nabu-kudurri-usur; c. 1119 BC-c. 1098 BC) is the best known ruler from this dynasty.

Chaldeans

Eventually, during the 800s BC, one of the most powerful tribes outside Babylon, the Chaldeans (Latin Chaldaeus, Greek Khaldaios, Assyrian Kaldu), gained prominence. The Chaldeans rose to power in Babylonia and, by doing so, seem to have increased the stability and power of Babylonia. They fought off many revolts and aggressors. Chaldean influence was so strong that, during this period, Babylonia came to be known as Chaldea.

In 626 BC, the Chaldeans helped Nabo-Polassar to take power in Babylonia. At that time, Assyria was under considerable pressure from an Iranian people, the Medes (from Media). Nabo-Polassar allied Babylonia with the Medes. Assyria could not withstand this added pressure, and in 612 BC, Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, fell. The entire city, once the capital of a great empire, was burned and sacked.

Nebuchadrezzar II of Babylon

Later, Nebuchadrezzar II (Nabopolassar's son) inherited the empire of Babylonia. He added quite a bit of territory to Babylonia and rebuilt Babylon, still the capital of Babylonia. Gal

In the 6th century BC (586 BC), Nebuchadrezzar II conquered Judea (Judah), destroyed Jerusalem; Solomon's Temple was also destroyed; Nebuchadrezzar II carried away an estimated 15,000 captives, and sent most of its population into exile in Babylonia. Nebuchadrezzar (604-562 BC) is credited for building the legendary Hanging Gardens of Babylon, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

Persian Domination; 550 BC to AD 652

Various invaders conquered the land after Nebuchadrezzar's death, including Cyrus the Great in 539 BC and Alexander the Great in 331 BC, who died there in 323 BC. In the sixth century BC, it became part of the Persian Empire, then was conquered by Alexander the Great and remained under Greek rule under the Seleucid dynasty for nearly two centuries. Babylon declined after the founding of Seleucia on the Tigris, the new Seleucid Empire capital. A Central Asian tribe of Iranian peoples called Parthians then annexed the region followed by the Sassanid Persians until the 7th century, when Arab Muslims captured it.

The Arabic term "Iraq", a derivative form of Persian Ērāk ("lower Iran") was not used at this time; in the mid-6th century the Iranian Empire under Sassanid dynasty was divided by Khosrow I into four quarters, of which the western one, called Khvārvarān, included most of modern Iraq, and subdivided to provinces of Mishān, Asuristān, Ādiābene and Lower Media. The term Iraq is widely used in the medieval Arabic sources for the area in the centre and south of the modern republic as a geographic rather than a political term, implying no precise boundaries.

The area of modern Iraq north of Tikrit was known in Muslim times as Al-Jazirah, which means "The Island" and refers to the "island" between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. To the south and west lay the Arabian deserts, inhabited largely by Arab tribesmen who occasionally acknowledged the overlordship of the Sassanian Emperors.

Until 602 the desert frontier of greater Iran had been guarded by the Lakhmid kings of Al-Hirah, who were themselves Arabs but who ruled a settled buffer state. In that year Shahanshah Khosrow II Aparviz (Persian خسرو پرويز) rashly abolished the Lakhmid kingdom and laid the frontier open to nomad incursions. Farther north, the western quarter was bounded by the Byzantine Empire. The frontier more or less followed the modern Syria-Iraq border and continued northward into modern Turkey, leaving Nisibis (modern Nusaybin) as the Sassanian frontier fortress while the Byzantines held Dara and nearby Amida (modern Diyarbakır).

to give a good sense those parts of Iraq, Syria and turkey which is inhabited by Kurds (one of Iranian race) was parts of Iran, Iraq was capital of Iran for more than 1000 years. after Islam the holey shitte places like Najaf and Karbala made Iraq the capital of shittie Muslims and center of Iranian civilization till establishment of modern Iraq. thats why even during worst times of war between Iran and Iraq under Saddam racist regime Iranians were calling Iraqis brothers. even now a days lots of Iraqis speaking Iranian languages like Kurdish and Farsi.

Ethnic diversity and Religion

The inhabitants of the region were very mixed at this time. There was an aristocratic and administrative Persian upper class, but most of the population were middle class Persian Zoroastrians and the rest Aramaic-speaking peasants. There were a number of Tāzis (Arabs), most of whom lived as pastoralists along the western margins of the settled lands, but some lived as townspeople, especially in Hireh (al-Hira). In addition, there were another group the Kurds, who lived along the foothills of the Zagros Mountains, and a surprisingly large number of Greeks, mostly prisoners captured during the numerous Sassanian campaigns into Byzantine Syria.

Ethnic diversity was matched by religious pluralism. The Sassanid state religion, Zoroastrianism, was largely confined to the Iranians. The rest of the population, especially in the northern part of the country, were probably Christians. These were sharply divided by doctrinal differences into Monophysites, linked to the Jacobite church of Syria, and Nestorians.

The Nestorians, who originally converted from Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism and Mazdakism, were the most widespread and were tolerated by the Sassanian Emperors because of their opposition to the Christians of the Roman Empire, who regarded the Nestorians as heretics. Many of those Iranian Nestorians were deported to southern provinces, located south of Persian Gulf, such as Mishmāhig (modern Bahrain and UAE), Garrhae (modern Saudi coast of Persian Gulf). The Monophysites were regarded with more suspicion and were occasionally persecuted, but both groups were able to maintain an ecclesiastical hierarchy, and the Nestorians had an important intellectual centre at Nisibis. The area around the ancient city of Babylon by this time had a large population of Jews, both descendants of the exiles of Old Testament times and local converts. In addition, in the southern half of the country there were numerous adherents of the old Babylonian paganism, as well as Mandaeans and Gnostics.

In the early 7th century the stability and prosperity of this multicultural society were threatened by invasion. In 602 Khosrow II Aparviz launched the last great Iranian invasion of the Byzantine Empire. At first he was spectacularly successful; Syria and Egypt fell, and Constantinople itself was threatened. Later the tide began to turn, and in 627-628 the Byzantines, under the leadership of the Heraclius, invaded Khvārvarān province and sacked the imperial capital at Tyspawn (Ctesiphon). The invaders did not remain, but Khosrow was discredited, deposed, and executed.

There followed a period of infighting among generals and members of the Imperial family that left the country without clear leadership. The chaos had also damaged irrigation systems, and it was probably at this time that large areas in the south of the country reverted to marshlands, which they have remained ever since. It was with this devastated land that the earliest Muslim raiders came into contact.

The Arab conquest and the early Islamic period

The first organised conflict between local Bedouin Arab tribes and Iranian forces seems to have been in 634, when the Arabs were defeated at the Battle of the Bridge. There was a force of some 5,000 Muslims under Abū `Ubayd ath-Thaqafī, which was routed by the Iranians. Around 636, a much larger Arab Muslim force under Sa`d ibn Abī Waqqās defeated the main Iranian army at the Battle of al-Qādisiyyah and moved on to sack the capital of the Iranian Empire, Ctesiphon. By the end of 638, the Muslims had conquered almost all of Western Iranian provinces (modern Iraq), and the last Sassanid Emperor, Yazdegerd III, had fled to central and then northern Iran, where he was killed in 651.

The Islamic conquest was followed by mass immigration of Arabs from eastern Arabia and Mazun (Oman) to Khvarvārān. These new arrivals did not disperse and settle throughout the country; instead they established two new garrison cities, at al-Kūfah, near ancient Babylon, and at Basrah in the south.

The intention was that the Muslims should be a separate community of fighting men and their families living off taxes paid by the local inhabitants. In the north of the North eastern Iran, Mosul began to emerge as the most important city and the base of a Muslim governor and garrison. Apart from the Iranian elite and the Zoroastrian priests, who did not convert to Islam and thus lost their lives and property, most of the Iranian peoples became Muslim and were allowed to keep their possessions.

Khvarvārān, now became a province of the Muslim Caliphate, known as `Irāq.

The Turkish Conquest

During the late 14th and early 15th centuries, the Black Sheep Turkmen ruled the area now known as Iraq. In 1466, the White Sheep Turkmen defeated the Black Sheep and took control. Later, most of Iraq would become part of the Safavid Empire that arose in Iran in 1501.

In the 16th century Iraq became a part of the Ottoman Empire, although the Safavids temporarily recaptured much of Iraq during the first part of the 17th century.

Modern History

Ottoman rule over Iraq lasted until the Great War (World War I) when the Ottomans sided with Germany and the Central Powers. British forces invaded the country and suffered a major defeat at the hands of the Turkish army during the Siege of Kut (1915–16). British forces regrouped and captured Baghdad in 1917. An armistice was signed in 1918.

Iraq was carved out of the Ottoman Empire by the French and British as agreed in the Sykes-Picot Agreement. On 11 November 1920 it became a League of Nations mandate under British control with the name "State of Iraq".

Britain imposed a Hāshimite monarchy on Iraq and defined the territorial limits of Iraq without taking into account the politics of the different ethnic and religious groups in the country, in particular those of the Kurds to the north. During the British occupation the Shiates and Kurds fought for independence. Britain used phosphorus bombs against Kurdish villagers in the revolt. Legal experts consider phosphorus bombs chemical weapons when used as an anti-personnel weapon.

In the Mandate period and beyond, the British supported the traditional, Sunni leadership (such as the tribal shaykhs) over the growing, urban-based nationalist movement. The Land Settlement Act gave the tribal shaykhs the right to register the communal tribal lands in their own name. The Tribal Disputes Regulations gave them judiciary rights, whereas the Peasants' Rights and Duties Act of 1933 severely reduced the tenants', forbidding them to leave the land unless all their debts to the landlord had been settled. The British resorted to military force when their interests were threatened, as in the 1941 Rashīd `Alī al-Gaylānī coup. This coup led to a British invasion of Iraq using forces from the British Indian Army and the Arab Legion from Jordan.

The Iraqi Monarchy

Emir Faisal, leader of the Arab revolt against the Ottoman sultān during the Great War, and member of the Sunni Hashimite family from Mecca, became the first king of the new state. He obtained the throne partly by the influence of T. E. Lawrence. Although the monarch was legitimized and proclaimed King by a plebiscite in 1921, nominal independence was only achieved in 1932, when the British Mandate officially ended.

In 1927, huge oil fields were discovered near Kirkuk and brought economic improvement. Exploration rights were granted to the Iraqi Petroleum Company, which despite the name, was a British oil company. King Faisal I was succeeded by his son Ghazi in December 1933. King Ghazi's reign lasted five and a half years. He claimed Iraqi sovereignty over Kuwait. An avid amateur racer, the king drove his car into a lamppost and died 3 April 1939. His son Faisal followed him to the throne.

King Faisal II (1935 – 1958) was the only son of King Ghazi I and Queen `Aliyah. The new king was four when his father died. His uncle 'Abd al-Ilah became regent (April 1939 – May 1953).

In 1945, Iraq joined the United Nations and became a founding member of the Arab League. At the same time, the Kurdish leader Mustafā Barzānī led a rebellion against the central government in Baghdad. After the failure of the uprising Barzānī and his followers fled to the Soviet Union.

In 1948, Iraq and five other Arab countries fought a war against the newly-declared State of Israel. Iraq was not a party to the cease-fire agreement signed in May 1949. The war had a negative impact on Iraq's economy. The government had to allocate 40 percent of available funds to the army and for the Palestinian refugees. Oil royalties paid to Iraq were halved when the pipeline to Haifa was cut. The war and the hanging of several Jewish businessmen led to the departure of most of Iraq's Jewish community.

Iraq signed the Baghdad Pact in 1956. It allied Iraq, Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, the United States and the United Kingdom. Its headquarters were in Baghdad. The Pact constituted a direct challenge to Egyptian president Gamal Abdal Nasser. In response, Nasser launched a media campaign that challenged the legitimacy of the Iraqi monarchy.

In February 1958, King Hussein of Jordan and `Abd al-Ilāh proposed a union of Hāshimite monarchies to counter the recently formed Egyptian-Syrian union. The prime minister Nuri as-Said wanted Kuwait to be part of the proposed Arab-Hāshimite Union. Shaykh `Abd-Allāh as-Salīm, the ruler of Kuwait, was invited to Baghdad to discuss Kuwait's future. This policy brought the government of Iraq into direct conflict with Britain, which did not want to grant independence to Kuwait. At that point, the monarchy found itself completely isolated. Nuri as-Said was able to contain the rising discontent only by resorting to ever greater political oppression.

See also List of Kings of Iraq.

The Republic

Inspired by Nasser, officers from the Nineteenth Brigade known as "Free Officers", under the leadership of Brigadier Abdul-Karim Qassem (known as "az-Za`īm", 'the leader') and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif overthrew the Hashimite monarchy on 14 July 1958. King Faisal II and `Abd al-Ilāh were executed in the gardens of ar-Rihāb Palace. Their bodies (and those of many others in the royal family) were displayed in public. Nuri as-Said evaded capture for one day, but after attempting to escape disguised as a veiled woman, he was caught and shot.

The new government proclaimed Iraq to be a republic and rejected the idea of a union with Jordan. Iraq's activity in the Baghdād Pact ceased.

When Qāsim distanced himself from `Abd an-Nāsir, he faced growing opposition from pro-Egypt officers in the Iraqi army. `Arif, who wanted closer cooperation with Egypt, was stripped of his responsibilities and thrown in prison.

When the garrison in Mosul rebelled against Qāsim's policies, he allowed the Kurdish leader Barzānī to return from exile in the Soviet Union to help suppress the pro-Nāsir rebels.

In 1961, Kuwait gained independence from Britain and Iraq claimed sovereignty over Kuwait. Britain reacted strongly to Iraq's claim and sent troops to Kuwait to deter Iraq. Qāsim was forced to back down and in October 1963, Iraq recognised the sovereignty of Kuwait.

A period of considerable instability followed. Qāsim was assassinated in February 1963, when the Ba'ath Party took power under the leadership of General Ahmed Hasan al-Bakr (prime minister) and Colonel Abdul Salam Arif (president). Nine months later `Abd as-Salam Muhammad `Arif led a successful coup against the Ba`th government. On 13 April 1966, President Abdul Salam Arif died in a helicopter crash and was succeeded by his brother, General Abdul Rahman Arif. Following the Six Day War of 1967, the Ba'ath Party felt strong enough to retake power (17 July 1968). Ahmad Hasan al-Bakr became president and chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council (RCC).

Barzānī and the Kurds who had begun a rebellion in 1961 were still causing problems in 1969. The secretary-general of the Ba`th party, Saddam Hussein, was given responsibility to find a solution. It was clear that it was impossible to defeat the Kurds by military means and in 1970 a political agreement was reached between the rebels and the Iraqi government.

Iraq's economy recovered sharply after the 1968 revolution. The Arif brothers had spent close to 90% of the national budget on the army but the Ba'ath government gave priority to agriculture and industry. The British Iraq Petroleum Company monopoly was broken when a new contract was signed with ERAP, a major French oil company. Later the IPC was nationalised. As a result of these policies Iraq experienced fast economic growth.

During the 1970s, border disputes with Iran and Kuwait caused many problems. Kuwait's refusal to allow Iraq to build an harbour in the Shatt al-Arab delta strengthened Iraq's belief that conservative powers in the region were trying to control the Persian Gulf. Iran's occupation of numerous islands in the Strait of Hormuz didn't help alter Iraq's fears. The border disputes between Iraq and Iran were temporarily resolved with the signing of the Algiers Accord on 6 March 1975.

In 1972 an Iraqi delegation visited Moscow. The same year diplomatic relations with the US were restored. Relations with Jordan and Syria were good. Iraqi troops were stationed in both countries. During the 1973 October War, Iraqi divisions engaged Israeli forces.

In retrospect, the 1970s can be seen as a high point in Iraq's modern history. A new, young, technocratic elite was governing the country and the fast growing economy brought prosperity and stability. Many Arabs outside Iraq considered it an example. However, the following decades would not be as favorable for the fledgling country.

Under Saddam

In July 1979, president Ahmed Hassan Al-Bakr resigned, and his chosen successor, Saddam Hussein, assumed the offices of both President and Chairman of the Revolutionary Command Council. He was the de facto ruler of Iraq for some years before he formally came to power.

Territorial disputes with Iran led to an inconclusive and costly eight-year war, the Iran-Iraq War (1980 – 1988, termed Qādisiyyat-Saddām – 'Saddam's Qādisiyyah'), eventually devastating the economy. Iraq declared victory in 1988 but actually achieved a weary return to the status quo ante bellum. The war left Iraq with the largest military establishment in the Persian Gulf region but with huge debts and an ongoing rebellion by Kurdish elements in the northern mountains. The government suppressed the rebellion by using weapons on civilian targets.

A mass chemical weapons attack on the city of Halabja in March 1988 during the Iran-Iraq War is usually attributed to Saddam's regime, although responsibility for the attack is a matter of some dispute[1] (Saddam maintains his innocence in this matter). Almost all current accounts of the incident regard the Iraqi regime as the party responsible for the gas attack (as opposed to Iran), and the event has become iconic in depictions of Saddam's cruelty. Estimates of casualties range from several hundred to at least 7,000 people. The Iraqi government continued to be supported by a broad international community including most of the West, the Soviet Union, and the People's Republic of China, which continued sending arms shipments to combat Iran. Indeed, shipments from the US (though always a minority) increased after this date, and the UK awarded £400 million in trade credits to Iraq ten days after condemning the massacre [3].

In the late 1970s, Iraq purchased a French nuclear reactor, dubbed Osirak or Tammuz 1. Construction began in 1979. In 1980, the reactor site suffered minor damage due to an Iranian air strike, and in 1981, before the reactor could be completed, it was destroyed by the Israeli Air Force (see Operation Opera), greatly setting back Iraq's nuclear weapons program.

Invasion of Kuwait and the Persian Gulf War

A long-standing territorial dispute led to the invasion of Kuwait in 1990. Iraq accused Kuwait of violating the Iraqi border to secure oil resources, and demanded that its debt repayments should be waived. Direct negotiations began in July 1990, but they soon failed. Saddam Hussein had an emergency meeting with April Glaspie, the United States Ambassador to Iraq, on 25 July 1990, airing his concerns but stating his intention to continue talks. April Glaspie informed Saddām that the United States had no interest in border disputes between Iraq and Kuwait.

Arab mediators convinced Iraq and Kuwait to negotiate their differences in Jiddah, Saudi Arabia, on 1 August 1990, but that session resulted only in charges and counter-charges. A second session was scheduled to take place in Baghdad, but Iraq invaded Kuwait the following day. Iraqi troops overran the country shortly after midnight on August 2, 1990. The United Nations Security Council and the Arab League immediately condemned the Iraqi invasion. Four days later, the Security Council imposed an economic embargo on Iraq that prohibited nearly all trade with Iraq.

Iraq responded to the sanctions by annexing Kuwait as the "19th Province" of Iraq on 8 August, prompting the exiled Sabah family to call for a stronger international response. Over the ensuing months, the United Nations Security Council passed a series of resolutions that condemned the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait and implemented total mandatory economic sanctions against Iraq. Other countries subsequently provided support for "Operation Desert Shield". In November 1990, the UN Security Council adopted Resolution 678, permitting member states to use all necessary means, authorising military action against the Iraqi forces occupying Kuwait and demanded a complete withdrawal by 15 January 1991.

When Saddam Hussein failed to comply with this demand, the Persian Gulf War (Operation "Desert Storm") ensued on January 17, 1991 (3am Iraqi time), with allied troops of 28 countries, led by the US launching an aerial bombardment on Baghdad. The war, which proved disastrous for Iraq, lasted only six weeks. One hundred and forty-thousand tons of munitions had showered down on the country, the equivalent of seven Hiroshima bombs. Probably as many as 100,000 Iraqi soldiers and tens of thousands of civilians were killed.

Allied air raids destroyed roads, bridges, factories, and oil-industry facilities (shutting down the national refining and distribution system) and disrupted electric, telephone, and water service. Conference centres and shopping and residential areas were hit. Hundreds of Iraqis were killed in the attack on the Al-Amiriyah bomb shelter. Diseases spread through contaminated drinking water because water purification and sewage treatment facilities could not operate without electricity.

A cease-fire was announced by the US on 28 February, 1991. UN Secretary-General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar met with Saddam Hussein to discuss the Security Council timetable for the withdraw of troops from Kuwait. Iraq agreed to UN terms for a permanent cease-fire in April 1991, and strict conditions were imposed, demanding the disclosure and destruction of all stockpiles of weapons.

Iraq under UN Sanction

See also: Iraq sanctions

On 6 August, 1990, after the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, the U.N. Security Council adopted Resolution 661 which imposed economic sanctions on Iraq, providing for a full trade embargo, excluding medical supplies, food and other items of humanitarian necessity, these to be determined by the Security Council sanctions committee. After the end of the Gulf War and after Iraqs withdrawal from Kuwait, the sanctions were linked to removal of weapons of mass destruction by Resolution 687[4].

The United States, citing a need to prevent the genocide of the Marsh Arabs in southern Iraq and the Kurds to the north, declared "air exclusion zones" north of the 36th parallel and south of the 32nd parallel. The Clinton administration judged an alleged assassination attempt on former President George H. W. Bush by Iraqi secret agents to be worthy of a military response on 27 June 1993. The Iraqi Intelligence Headquarters in Baghdad was targeted by Tomahawk cruise missiles.

During the time of the UN sanctions, internal and external opposition to the Ba'ath government was weak and divided. In May 1995, Saddam sacked his half-brother, Wathban, as Interior Minister and in July demoted his Defense Minister, Ali Hassan al-Majid. These personnel changes were the result of the growth in power of Saddām Hussein's two sons, Uday Hussein and Qusay Hussein, who were given effective vice-presidential authority in May 1995. In August Major General Husayn Kāmil Hasan al-Majīd, Minister of Military Industries and a political ally of Saddam, defected to Jordan, together with his wife (one of Saddam's daughters) and his brother, Saddam, who was married to another of the president's daughters; both called for the overthrow of the Iraqi government. After a few weeks in Jordan, being given promises for their safety, the two brothers returned to Iraq where they were killed.

During the latter part of the 1990s the UN considered relaxing the sanctions imposed because of the hardships suffered by ordinary Iraqis. According to UN estimates, between 500,000 and 1.2 million children died[5] during the years of the sanctions. The United States used its veto in the UN Security Council to block the proposal to lift the sanctions because of the continued failure of Iraq to verify disarmament. However, an oil for food program was established in 1996 to ease the effects of sanctions.

Iraqi cooperation with UN weapons inspection teams was questioned on several occasions during the 1990s. UNSCOM chief weapons inspector Richard Butler withdrew his team from Iraq in November 1998 because of Iraq's lack of cooperation. The team returned in December.[2] Butler prepared a report for the UN Security Council afterwards in which he expressed dissatisfaction with the level of compliance [6]. The same month, US President Bill Clinton authorized air strikes on government targets and military facilities. Air strikes against military facilities and alleged WMD sites continued into 2002.

2003 invasion of Iraq

- Main article: 2003 invasion of Iraq.

After the terrorist attacks by the group formed by the multi-millionaire Saudi Osama bin Laden on New York and Washington in the United States in 2001, American foreign policy began to call for the removal of the Ba'ath government in Iraq. Conservative think-tanks in Washington had for years been urging regime change in Baghdad, but until the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, official US policy was to simply keep Iraq complying with UN sanctions. In addition, unofficial US policies, including a CIA backed coup attempt, were aimed at removing Saddam Hussein from power. After the terrorist attacks of September 11th, regime change became official policy. The occupation of Iraq later was identified by the George W. Bush administration as a part of the global War on Terrorism.

The US urged the United Nations to take military action against Iraq. The American president George Bush stated that Saddām had repeatedly violated 16 UN Security Council resolutions. The Iraqi government rejected Bush's assertions. A team of U.N. inspectors, led by Swedish diplomat Hans Blix was admitted, into the country; their final report stated that Iraqis capability in producing "weapons of mass destruction" was not significantly different from 1992 when the country dismantled the bulk of their remaining arsenals under terms of the ceasefire agreement with U.N. forces, but did not completely rule out the possibility that Saddam still had Weapons of Mass Destruction. The United States and the United Kingdom charged that Iraq was hiding Weapons and opposed the team's requests for more time to further investigate the matter. Resolution 1441 was passed unanimously by the UN Security Council on November 8, 2002, offering Iraq "a final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations" that had been set out in several previous UN resolutions, threatening "serious consequences" if the obligations were not fulfilled. The UN Security Council did not issue a resolution authorizing the use of force against Iraq.

In March 2003 the United States and the United Kingdom, with military aid from other nations, invaded Iraq.

Coalition occupation of Iraq

In 2003, after the American and British invasion, Iraq was occupied by Coalition forces. On 23 May 2003, the UN Security Council unanimously approved a resolution lifting all economic sanctions against Iraq.

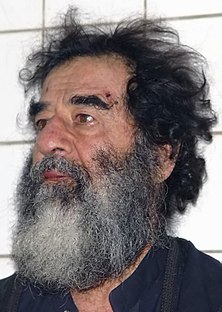

As the country struggled to rebuild after three wars and a decade of sanctions, it was racked by violence between a growing Iraqi insurgency and occupation forces. Saddam Hussein, who vanished in April, was captured on 13 December, 2003.

The initial US interim civil administrator, Jay Garner, was replaced in May 2003 by L. Paul Bremer, who was himself replaced by John Negroponte in 19 April 2004 who left Iraq in 2005. Negroponte was the last US interim administrator.

Terrorism emerged as a threat to Iraq's people not long after the invasion of 2003. Al Qaeda now has a presence in the country, in the form of several terrorist groups formerly led by Abu Musab Al Zarqawi. Many foreign fighters and former Ba'ath Party officials have also joined the insurgency, which is mainly aimed at attacking American forces and Iraqis who work with them. The most dangerous insurgent area is the Sunni Triangle, a mostly Sunni-Muslim area just north of Baghdad.

Coalition withdrawal

- Main article: Iraq after Saddam Hussein

A few days after the 11 March 2004 Madrid attacks, the conservative government of Spain was voted out of office. The War had been deeply unpopular and the incoming Socialist government followed through on its manifesto commitment to withdraw troops from Iraq. Following on the heels of this, several other nations that once formed the Coalition of the Willing began to reconsider their role. The Dutch refused a US offer to commit their troops to Iraq past 30 June. South Korea kept its troops deployed.

Soon after the decisions to withdrawal in the Spring of 2004, the Dominican Republic, Honduran, Guatemala, Kazakhstan, Singapore, Thailand, Portugal, Philippines, Bulgaria, Nicaragua and Italy left or are planning to leave as well. Other nations (such as Australia, Denmark and Poland) continued their commitment in Iraq.

On 28 June 2004, the occupation was formally ended by the U.S.-led coalition, which transferred power to an interim Iraqi government led by Prime Minister Iyad Allawi. On 16 July 2004, the Philippines ordered the withdrawal of all of its troops in Iraq in order to comply with the demands of terrorists holding Filipino citizen Angelo de la Cruz as a hostage. Many nations that have announced withdrawal plans or are considering them have stated that they may reconsider if there is a new UN resolution that grants the UN more authority in Iraq.

The Iraqi government has officially requested the assistance of (at least) American troops until further notice.

On January 30, 2005. the transitional parliamentary elections took place. See: Iraqi legislative election, January 2005.

Post-invasion violence

Violence continued as the new Iraqi Government struggled to maintain security within Iraq, and its own legitimacy by the end of 2006. U.S. forces, as well as lesser amounts of "coalition" forces remained in Iraq. An increasingly disturbing trend had arisen; sectarian fighting. A new phase of conflict had erupted within Iraq, as the country attempted to move from occupation by western forces to a new entity within the Middle East. This new phase of conflict waged predominately along religious sect lines, primarily the majority (and newly politically powerful) Shia and the minority Sunni (which once were the primary ruling sect of Iraq under Saddam's Ba'ath regime).

Acts of violence conducted by an uneasy tapestry of Sunni militants had been steadily increasing by the end of 2006. These attacks become predominately aimed at Iraqi civilians rather than coalition forces. Violence was conducted by Sunni militants that include the Iraq Insurgency, which has been fighting since the initial U.S. invasion of 2003. Also, criminal elements within Iraq's society seemed to perpetuate violence for their own means and ambitions. Iraqi nationalist and Ba'athist elements (part of the insurgency) remained committed to expelling U.S. forces and also seemed to attack Shia populations, presumably, due to the Shia's threat to the Ba'athis aspirations. Further Islamic Jihadist, of which Al Qaeda in Iraq is a member, continued to use terror and extreme acts of violence against civilian populations to formant their religious and political agenda(s). The aims of these attacks were not completely clear as 2006 ended, but it was argued at the time that these attacks were aimed at fomenting civil conflict within Iraq to destroy the legitimacy of the newly created Iraqi government (which many of its Sunni critics saw as illegitimate and a product of the U.S. government) and create an unsustainable position for the U.S. forces within Iraq.

In response, Shia militia organizations associated with various factions of the majority sect of Shia Islam within Iraq gained increasing power and influence on the Iraqi government. Additionally, the militias, it appeared in late 2006, had the capability to act outside the scope of government. As a result these powerful militias, it seemed as of late 2006, were leading reprisal acts of violence against the Sunni minority. A cycle of violence had thus ensued whereby Sunni insurgent or terrorist attacks followed with Shia reprisals - often in the form of Shi'ite death squads that sought out and killed Sunnis. Many commentators on the Iraq War began, by the end of 2006, to refer to this violent escalation as a civil war. As 2006 ended the situation in Iraq had become disastrous for most involved, most emphatically, however, for the civilian population of Iraq.

Kurdish north

Nouri al-Maliki was at loggerheads with the leader of ethnic Kurds, who brandished the threat of secession in a growing row over the symbolic issue of flying the Iraqi national flag at government buildings in the autonomous Kurdish north. Maliki's Arab Shi'ite-led government was locked in a dispute with the autonomous Kurdish regional government, which has banned the use of the Iraqi state flag on public buildings. The prime minister issued a statement saying: "The Iraqi flag is the only flag that should be raised over any square inch of Iraq." But Mesud Barzani, president of the Kurdistan region, told the Kurdish parliament the national leadership were "failures" and that the Iraqi flag was a symbol of his people's past oppression by Baghdad: "If at any moment we, the Kurdish people and parliament, consider that it is in our interests to declare independence, we will do so and we will fear no one." The dispute exposes a widening rift between Arabs and Kurds, the second great threat to Iraq's survival as a state after the growing sectarian conflict between Arab Sunnis and Shi'ites.

Execution of Saddam Hussein

-See Execution of Saddam Hussein

With the death by execution of Iraq's long standing Saddam Hussein, Iraq moves into a new uncertain and important period of its history.

References

- ^ The US Defense Intelligence Agency reported that the attack was carried out by Iran, a version of events supported by the CIA during the early 1990s [1]. See also an opinion piece by CIA analyst Stephen C Pelletiere, in which he conlcudes that there is no basis for a judgement as to whether Iran or Iraq was responsible for the attack [2].

- ^ Richard BUTLER, Saddam Defiant, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, 2000, p. 224

See also

- Iraq

- Reconstruction of Iraq

- President of Iraq

- Prime Minister of Iraq

- Kurdistan

- History of the Kurds

- Yazidism

- Mesopotamia

- Mesopotamian mythology